Plasmodium knowlesi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Plasmodium knowlesi'' is a parasite that causes

''P. knowlesi'' largely resembles other ''Plasmodium'' species in its cell biology. Its genome consists of 23.5

''P. knowlesi'' largely resembles other ''Plasmodium'' species in its cell biology. Its genome consists of 23.5

''P. knowlesi'' can cause both uncomplicated and

''P. knowlesi'' can cause both uncomplicated and

CDC malaria pageWHO malaria pageP. knowlesi genome data

{{DEFAULTSORT:Plasmodium Knowlesi knowlesi Parasites of primates

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

in humans and other primates. It is found throughout Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, and is the most common cause of human malaria in Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

. Like other ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ve ...

'' species, ''P. knowlesi'' has a life cycle that requires infection of both a mosquito and a warm-blooded host. While the natural warm-blooded hosts of ''P. knowlesi'' are likely various Old World monkey

Old World monkey is the common English name for a family of primates known taxonomically as the Cercopithecidae (). Twenty-four genera and 138 species are recognized, making it the largest primate family. Old World monkey genera include baboons ...

s, humans can be infected by ''P. knowlesi'' if they are fed upon by infected mosquitoes. ''P. knowlesi'' is a eukaryote in the phylum Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. Th ...

, genus ''Plasmodium'', and subgenus ''Plasmodium''. It is most closely related to the human parasite ''Plasmodium vivax

''Plasmodium vivax'' is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than ''Plasmodium falciparum'', the deadliest of the five huma ...

'' as well as other ''Plasmodium'' species that infect non-human primates.

Humans infected with ''P. knowlesi'' can develop uncomplicated or severe malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

similar to that caused by ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female '' Anopheles'' mosquito and causes the ...

''. Diagnosis of ''P. knowlesi'' infection is challenging as ''P. knowlesi'' very closely resembles other species that infect humans. Treatment is similar to other types of malaria, with chloroquine

Chloroquine is a medication primarily used to prevent and treat malaria in areas where malaria remains sensitive to its effects. Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases typically require different or additional medi ...

or artemisinin combination therapy

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young c ...

typically recommended. ''P. knowlesi'' malaria is an emerging disease previously thought to be rare in humans, but increasingly recognized as a major health burden in Southeast Asia.

''P. knowlesi'' was first described as a distinct species and as a potential cause of human malaria in 1932. It was briefly used in the early 20th century to cause fever as a treatment for neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis refers to infection of the central nervous system in a patient with syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been reported in HIV-infected patients. Meningitis is the most common neurologic ...

. In the mid-20th century, ''P. knowlesi'' became popular as a tool for studying ''Plasmodium'' biology and was used for basic research, vaccine research, and drug development. ''P. knowlesi'' is still used as a laboratory model for malaria, as it readily infects the model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

primate the rhesus macaque

The rhesus macaque (''Macaca mulatta''), colloquially rhesus monkey, is a species of Old World monkey. There are between six and nine recognised subspecies that are split between two groups, the Chinese-derived and the Indian-derived. Generally ...

, and can be grown in cell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. The term "tissue culture" was coined by American pathologist Montrose Thomas Burrows. This tec ...

in human or macaque blood.

Life cycle

Like other ''Plasmodium'' parasites, ''P. knowlesi'' has a life cycle that requires it be passed back and forth between mammalian hosts and insect hosts. Primates are infected through the bite of an infected ''Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described and named by J. W. Meigen in 1818. About 460 species are recognised; while over 100 can transmit human malaria, only 30–40 commonly transmit parasites of the genus ''Plasmodium'', which ...

'' mosquito which carries a parasite stage called the sporozoite

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is ...

in its salivary glands. Sporozoites follow the blood stream to the primate liver where they develop and replicate over five to six days before bursting, releasing thousands of daughter cells called merozoite

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism i ...

s into the blood (unlike the related ''P. vivax'', ''P. knowlesi'' does not make latent hypnozoite

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a verteb ...

s in the liver). The merozoites in the blood attach to and invade the primate's red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "hol ...

s. Inside the red blood cell, the parasite progresses through several morphologically distinguishable stages, called the ring stage, the trophozoite, and the schizont. The schizont-infected red blood cells eventually burst, releasing up to 16 new merozoites into the blood stream that infect new red blood cells and continue the cycle. ''P. knowlesi'' completes this red blood cell cycle every 24 hours, making it uniquely rapid among primate-infecting ''Plasmodium'' species (which generally take 48 or 72 hours). Occasionally, parasites that invade red blood cells instead enter a sexual cycle, developing over approximately 48 hours into distinct sexual forms called microgametocytes or macrogametocytes. These gametocytes remain in the blood to be ingested by mosquitoes.

A mosquito ingests gametocytes when it takes a blood meal from an infected primate host. Once inside the mosquito gut, the gametocytes develop into gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

s and then fuse to form a diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectiv ...

zygote. The zygote matures into an ookinete

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is ...

, which migrates through the wall of the mosquito gut and develops into an oocyst

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is ...

. The oocyst then releases thousands of sporozoites, which migrate through the mosquito to the salivary glands. This entire process in the mosquito takes 12 to 15 days.

Cell biology

''P. knowlesi'' largely resembles other ''Plasmodium'' species in its cell biology. Its genome consists of 23.5

''P. knowlesi'' largely resembles other ''Plasmodium'' species in its cell biology. Its genome consists of 23.5 megabase

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both ...

s of DNA separated into 14 chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s. It contains approximately 5200 protein-coding genes, 80% of which have ortholog

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a s ...

s present in ''P. falciparum'' and ''P. vivax''. The genome contains two large gene families that are unique to ''P. knowlesi'': the SICAvar (schizont-infected cell agglutination variant) family, which is involved in displaying different antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune respon ...

s on the parasite surface to evade the immune system, and the Kir (knowlesi interspersed repeat) family, involved in adhering parasitized red blood cells to blood vessel walls.

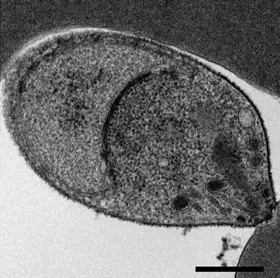

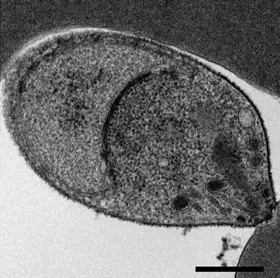

As an apicomplexan

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. The ...

, ''P. knowlesi'' has several distinctive structures at its apical end that are specialized for invading host cells. These include the large bulbous rhoptries, smaller micronemes, and dispersed dense granule

Dense granules (also known as dense bodies or delta granules) are specialized secretory organelles. Dense granules are found only in platelets and are smaller than alpha granules.Michelson, A. D. (2013). ''Platelets'' (Vol. 3rd ed). Amsterdam: Ac ...

s, each of which secretes effectors to enter and modify the host cell. Like other apicomplexans, ''P. knowlesi'' also has two organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' th ...

s of endosymbiotic origin: a single large mitochondrion

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is use ...

and the apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including ''Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium' ...

, both of which are involved in the parasite's metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

.

Evolution and taxonomy

Despite its morphological similarity to ''P. malariae'', ''P. knowlesi'' is most closely related to ''P. vivax'' as well as other ''Plasmodium'' species that infect non-human primates. The last common ancestor of all modern ''P. knowlesi'' strains lived an estimated 98,000 to 478,000 years ago. Among human parasites, ''P. knowlesi'' is most closely related to ''P. vivax'', from which it diverged between 18 million and 34 million years ago. Aphylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

comparing the ''Plasmodium'' species that infect humans is shown below:

The population of ''P. knowlesi'' parasites is more genetically diverse than that of ''P. falciparum'' or ''P. vivax''. Within ''P. knowlesi'' there are three genetically distinct subpopulations. Two are present in the same areas of Malaysian Borneo and may infect different mosquitoes. The third has been found only in laboratory isolates originating from other parts of Southeast Asia. Populations of ''P. knowlesi'' isolated from macaques are genetically indistinguishable from those isolated from human infections, suggesting the same parasite populations can infect humans and macaques interchangeably.

Three subspecies of ''P. knowlesi'' have been described based on differences in their appearance in stained blood films: ''P. knowlesi edesoni'', ''P. knowlesi sintoni'', and ''P. knowlesi arimai'', which were isolated from Malaysia, Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, and Taiwan respectively. The relationship between these described subspecies and the populations described in the modern literature is not clear.

Distribution

''Plasmodium knowlesi'' is found throughoutSoutheast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, where it primarily infects the long-tailed macaque, pig-tailed macaque The pig-tailed macaques are two macaque sister species. They look almost identical and are best distinguished by their parapatric ranges:

* Northern pig-tailed macaque, ''Macaca leonina'' (Bangladesh to Vietnam, south to northern Malaysia)

* Sout ...

, and Sumatran surili

The black-crested Sumatran langur (''Presbytis melalophos'') is a species of primate in the family Cercopithecidae. It is endemic to Sumatra in Indonesia. Its natural habitat is subtropical or tropical dry forests. It is threatened by habitat los ...

as well as the mosquito vectors '' Anopheles hackeri'' in peninsular Malaysia and '' Anopheles latens'' in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

. Long-tailed macaques in the wild can be infected with ''P. knowlesi'' without any apparent disease, even when they are simultaneously infected with various other ''Plasmodium'' species. ''P. knowlesi'' is rarely found outside of Southeast Asia, likely because the mosquitoes it infects are restricted to that region.

Role in human disease

''P. knowlesi'' can cause both uncomplicated and

''P. knowlesi'' can cause both uncomplicated and severe

Severity or Severely may refer to:

* ''Severity'' (video game), a canceled video game

* "Severely" (song), by South Korean band F.T. Island

See also

*

*

{{disambig ...

malaria in humans. Those infected nearly always experience fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

and chills

Chills is a feeling of coldness occurring during a high fever, but sometimes is also a common symptom which occurs alone in specific people. It occurs during fever due to the release of cytokines and prostaglandins as part of the inflammatory ...

. People with uncomplicated ''P. knowlesi'' malaria often also experience headaches, joint pain, malaise

As a medical term, malaise is a feeling of general discomfort, uneasiness or lack of wellbeing and often the first sign of an infection or other disease. The word has existed in French since at least the 12th century.

The term is often used ...

, and loss of appetite. Less commonly, people report coughing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Laboratory tests of infected people nearly always show a low platelet count

Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets, also known as thrombocytes, in the blood. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients and ...

, although this rarely leads to bleeding problems. Unlike other human malarias, ''P. knowlesi'' malaria tends to have fevers that spike every 24 hours, and is therefore often called daily or "quotidian" malaria. Uncomplicated ''P. knowlesi'' malaria can be treated with antimalarial drugs

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young c ...

.

At least 10% of people infected with ''P. knowlesi'' develop severe malaria. Severe ''P. knowlesi'' malaria resembles severe malaria caused by ''P. falciparum''. Those with severe disease may experience shortness of breath, abdominal pain, and vomiting. As disease progresses, parasites replicate to very high levels in the blood likely causing acute kidney injury, jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme meta ...

, shock, and respiratory distress. Metabolic acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is a serious electrolyte disorder characterized by an imbalance in the body's acid-base balance. Metabolic acidosis has three main root causes: increased acid production, loss of bicarbonate, and a reduced ability of the kidneys ...

is uncommon, but can occur in particularly severe cases. Unlike ''P. falciparum'' malaria, severe ''P. knowlesi'' malaria rarely causes coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

or severe anemia

Anemia or anaemia (British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. When anemia comes on slowly, t ...

. Approximately 1-2% of cases are fatal.

Diagnosis

Malaria is traditionally diagnosed by examining Giemsa-stained blood films under a microscope; however, differentiating ''P. knowlesi'' from other ''Plasmodium'' species in this way is challenging due to their similar appearance. ''P. knowlesi'' ring-stage parasites stained with Giemsa resemble ''P. falciparum'' ring stages, appearing as a circle with one or two dark dots ofchromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important ...

. Older trophozoites appear more dispersed, forming a rectangular-shape spread across the host cell called a "band-form" that resembles the similar stage in ''P. malariae''. During this stage, dots sometimes appear across the host red blood cell, called "Sinton and Mulligans' stippling". Schizonts appear, similarly to other ''Plasmodium'' species, as clusters of purple merozoites surrounding a central dark-colored pigment.

Due to the morphological similarity among ''Plasmodium'' species, misdiagnosis of ''P. knowlesi'' infection as ''P. falciparum'', ''P. malariae'', or ''P. vivax'' is common. While some rapid diagnostic test

A rapid diagnostic test (RDT) is a medical diagnostic test that is quick and easy to perform. RDTs are suitable for preliminary or emergency medical screening and for use in medical facilities with limited resources. They also allow point-of-care ...

s can detect ''P. knowlesi'', they tend to have poor sensitivity and specificity

''Sensitivity'' and ''specificity'' mathematically describe the accuracy of a test which reports the presence or absence of a condition. Individuals for which the condition is satisfied are considered "positive" and those for which it is not are ...

and are therefore not always reliable. Detection of nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main ...

by PCR or real-time PCR

A real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR, or qPCR) is a laboratory technique of molecular biology based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It monitors the amplification of a targeted DNA molecule during the PCR (i.e., in real ...

is the most reliable method for detecting ''P. knowlesi'', and differentiating it from other ''Plasmodium'' species infection. However, due to the relatively slow and expensive nature of PCR, this is not available in many endemic areas. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is a single-tube technique for the amplification of DNA and a low-cost alternative to detect certain diseases. Reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) combines LAMP with ...

methods of ''P. knowlesi'' detection have also been developed, but are not yet widely used.

Treatment

Because ''P. knowlesi'' takes only 24 hours to complete its erythrocytic cycle, it can rapidly result in very high levels of parasitemia with fatal consequences. For those withuncomplicated malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue (medical), tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In se ...

, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

recommends treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapy

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young ...

(ACT) or chloroquine

Chloroquine is a medication primarily used to prevent and treat malaria in areas where malaria remains sensitive to its effects. Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases typically require different or additional medi ...

. For those with severe malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, the World Health Organization recommends administration of intravenous artesunate

Artesunate (AS) is a medication used to treat malaria. The intravenous form is preferred to quinine for severe malaria. Often it is used as part of combination therapy, such as artesunate plus mefloquine. It is not used for the prevention of ...

for at least 24 hours, followed by ACT treatment. Additionally, early drug trials have suggested that combinations of chloroquine and primaquine

Primaquine is a medication used to treat and prevent malaria and to treat ''Pneumocystis'' pneumonia. Specifically it is used for malaria due to ''Plasmodium vivax'' and '' Plasmodium ovale'' along with other medications and for prevention if oth ...

, artesunate and mefloquine

Mefloquine, sold under the brand name Lariam among others, is a medication used to prevent or treat malaria. When used for prevention it is typically started before potential exposure and continued for several weeks after potential exposure. It ...

, artemether and lumefantrine, and chloroquine alone could be effective treatments for uncomplicated ''P. knowlesi'' malaria. There is no evidence of ''P. knowlesi'' developing resistance to current antimalarials.

Epidemiology

''P. knowlesi'' is the most common cause of malaria inMalaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

, and cases of ''P. knowlesi'' malaria have been reported in most countries of Southeast Asia as well as travelers from the region.

Infection with ''P. knowlesi'' is associated with socioeconomic and lifestyle factors that bring people into the dense forests where the mosquito hosts are commonly found. In particular, those who work in the forest or at its margin such as farmers, hunters, and loggers are at increased risk for infection. Likely for this reason, males are infected more frequently than females, and adults are infected more frequently than children.

Research

''P. knowlesi'' has long been used as a research model for studying the interaction between parasite and host, and developing antimalarial vaccines and drugs. Its utility as a research model is partly due to its ability to infect rhesus macaques, a common laboratory model primate. Rhesus macaques are highly susceptible to ''P. knowlesi'' and can be infected by mosquito bite, injection of sporozoites, or injection of blood-stage parasites. Infected monkeys develop some hallmarks of human malaria including anemia and enlargement of the spleen and liver. Infection is typically fatal if untreated, with the cause of death seeminglycirculatory

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, t ...

failure characterized by adhesion of infected red blood cells to the blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide awa ...

walls. Monkeys can be cured of infection by treatment with antimalarials; repeated infection followed by cure results in the monkeys developing some immunity to infection, a topic that has also been the subject of substantial research.

''P. knowlesi'' is also used for ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called " test-tube experiments", these studies in biology a ...

'' research into ''Plasmodium'' cell biology. Isolated sporozoites can infect primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

...

rhesus hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, ...

s, allowing the ''in vitro'' study of the parasite liver stage. Additionally, ''P. knowlesi'' and ''P. falciparum'' are the only ''Plasmodium'' species that can be maintained continuously in cultured red blood cells, both rhesus and human. Facilitating molecular biology research, the ''P. knowlesi'' genome has been sequenced and is available on PlasmoDB PlasmoDB is a ''biological database'' for the genus ''Plasmodium''. The database is a member of the '' EuPathDB'' project. The database contains extensive ''genome'', ''proteome'' and ''metabolome'' information relating to malaria parasites.

See al ...

and other online repositories. ''P. knowlesi'' can be genetically modified in the lab by transfection

Transfection is the process of deliberately introducing naked or purified nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells. It may also refer to other methods and cell types, although other terms are often preferred: " transformation" is typically used to des ...

either in the rhesus macaque model system, or in blood cell culture. Blood-infecting stages and sporozoites can be stored long-term by freezing with glycerolyte, allowing the preservation of strains of interest.

History

The Italian physician Giuseppe Franchini first described what may have been ''P. knowlesi'' in 1927 when he noted a parasite distinct from '' P. cynomolgi'' and '' P. inui'' in the blood of a long-tailed macaque.Franchini G (1927) Su di un plasmodio pigmentato di una scimmia. Arch Ital Sci Med Colon 8:187–90 In 1931, the parasite was again seen in a long-tailed macaque by H. G. M. Campbell during his work on ''kala azar'' (visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar ( Hindi: kālā āzār, "black sickness") or "black fever", is the most severe form of leishmaniasis and, without proper diagnosis and treatment, is associated with high fatality. Leishmanias ...

) in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

; Campbell's colleague Lionel Everard Napier

L. Everard Napier (9 October 1888, Preston, Lancashire – 15 December 1957, Silchester, Hampshire) was a British tropical physician and professor of tropical medicine, known for his 1946 textbook ''Principles and Practice of Tropical Medicine'' a ...

drew blood from the affected monkey and inoculated three laboratory monkeys, one of which was a rhesus macaque that developed a severe infection. Campbell and Napier gave the infected monkey to Biraj Mohan Das Gupta who was able to maintain the parasite by serial passage through monkeys. In 1932, Das Gupta and his supervisor Robert Knowles described the morphology of the parasite in macaque blood, and demonstrated that it could infect three human patients (in each case it was used to induce fever with the hope of treating another infection). Also in 1932, John Sinton and H. W. Mulligan further described the morphology of the parasite in blood cells, determined it to be a distinct species from others described, and named it ''Plasmodium knowlesi'' in honor of Robert Knowles.

Soon thereafter, in 1935 C. E. Van Rooyen and George R. Pile reported using ''P. knowlesi'' infection to treat general paralysis

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

in psychiatric patients. ''P. knowlesi'' would go on to be used as a general pyretic agent for various diseases, particularly neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis refers to infection of the central nervous system in a patient with syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been reported in HIV-infected patients. Meningitis is the most common neurologic ...

for which it was used until at least 1955. While Cyril Garnham

Percy Cyril Claude Garnham CMG FRS (15 January 1901 – 25 December 1994), was a British biologist and parasitologist. On his 90th birthday, he was called the "greatest living parasitologist".

Early life and education

Garnham was born in Lo ...

had suggested in 1957 that ''P. knowlesi'' might naturally infect humans, the first documented case of a human naturally infected with ''P. knowlesi'' was in 1965 in a U.S. Army surveyor who developed chills and fever after a five-day deployment in Malaysia. Based on this finding, a team at the Institute for Medical Research in Peninsular Malaysia undertook a survey of people living in proximity to macaques, but failed to find evidence that simian malaria was being transmitted to humans.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, scientific research groups used ''P. knowlesi'' as a research model to make seminal discoveries in malaria. In 1965 and 1972, several groups characterized how ''P. knowlesi'' antigenic variation contributed to immune evasion and chronic infection. In 1975, Louis H. Miller Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ...

and others showed that ''P. knowlesi'' required Duffy factor on the surface of red blood cells in order to invade them (they would go on to show the same requirement for ''P. vivax'' a year later).

Work on ''P. knowlesi'' as a human malaria parasite was revitalized in 2004, when Balbir Singh and others used PCR to show that over half of a group of humans diagnosed with ''P. malariae'' malaria in Malaysian Borneo were actually infected with ''P. knowlesi''. Over the following decade, several investigators used molecular detection methods capable of distinguishing ''P. knowlesi'' from morphologically similar parasites to attribute an increasing proportion of malaria cases to ''P. knowlesi'' throughout Southeast Asia. Work with archival samples has shown that infection with this parasite has occurred in Malaysia at least since the 1990s.

References

External links

CDC malaria page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Plasmodium Knowlesi knowlesi Parasites of primates