Piano Concerto No. 1 (Tchaikovsky) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in

According to Alan Walker, the concerto was so popular that Bülow was obliged to repeat the Finale, a fact that Tchaikovsky found astonishing. Although the premiere was a success with the audience, the critics were not so impressed. One wrote that the piece was "hardly destined ..to become classical".

The introduction's theme is notable for its apparent formal independence from the rest of the movement and the concerto as a whole, especially given its setting not in the work's nominal key of B minor but rather in

The introduction's theme is notable for its apparent formal independence from the rest of the movement and the concerto as a whole, especially given its setting not in the work's nominal key of B minor but rather in

Tchaikovsky Research

{{authority control Concertos by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

B minor

B minor is a minor scale based on B, consisting of the pitches B, C, D, E, F, G, and A. Its key signature has two sharps. Its relative major is D major and its parallel major is B major.

The B natural minor scale is:

:

Changes need ...

, Op. 23, was composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most pop ...

between November 1874 and February 1875.Maes, 75. It was revised in 1879 and in 1888. It was first performed on October 25, 1875, in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

by Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, virtuoso pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for es ...

after Tchaikovsky's desired pianist, Nikolai Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich Tc ...

, criticised the piece. Rubinstein later withdrew his criticism and became a fervent champion of the work. It is one of the most popular of Tchaikovsky's compositions and among the best known of all piano concerti.

From 2021 to 2022, it served as the sporting anthem of the Russian Olympic Committee as a substitute of the country's actual national anthem as a result of the doping scandal that prohibits the use of its national symbols.

History

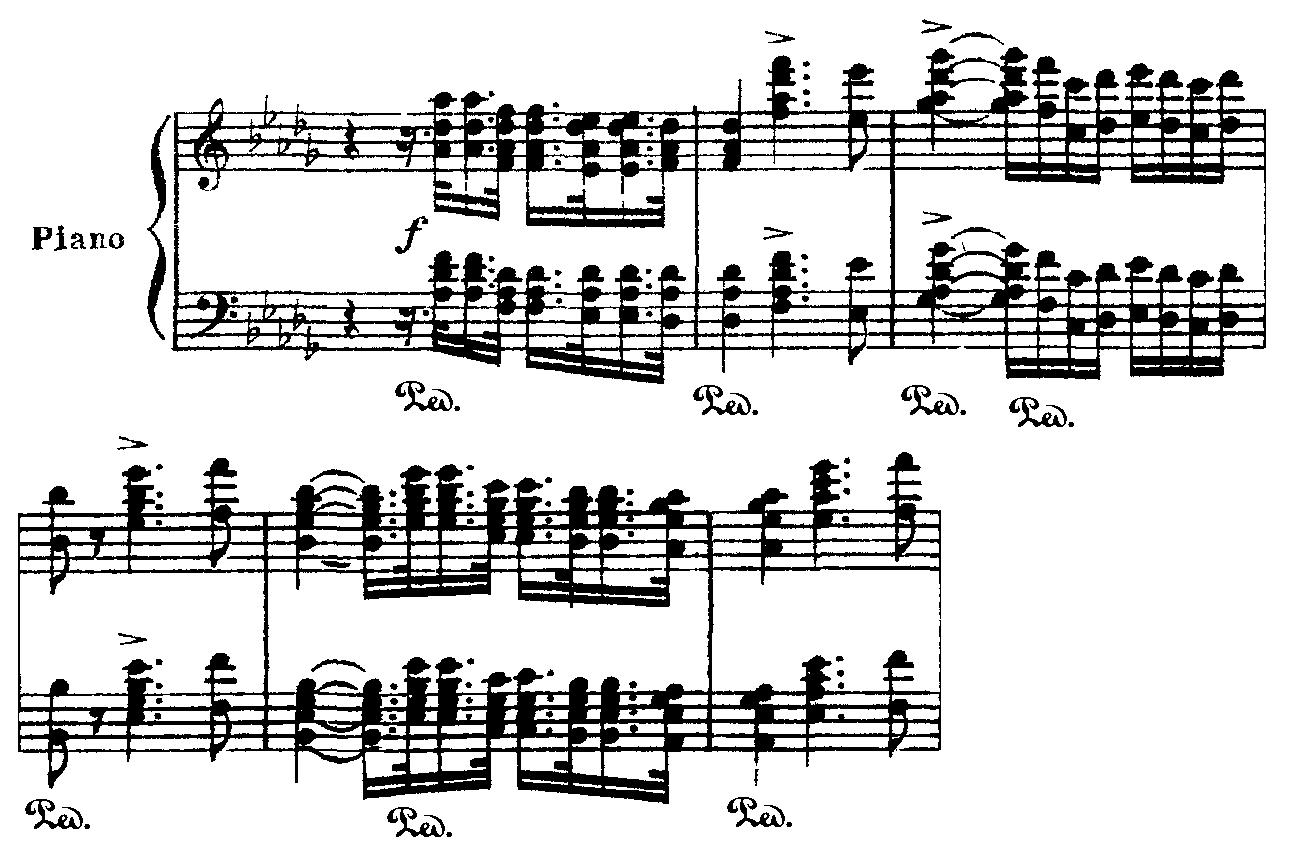

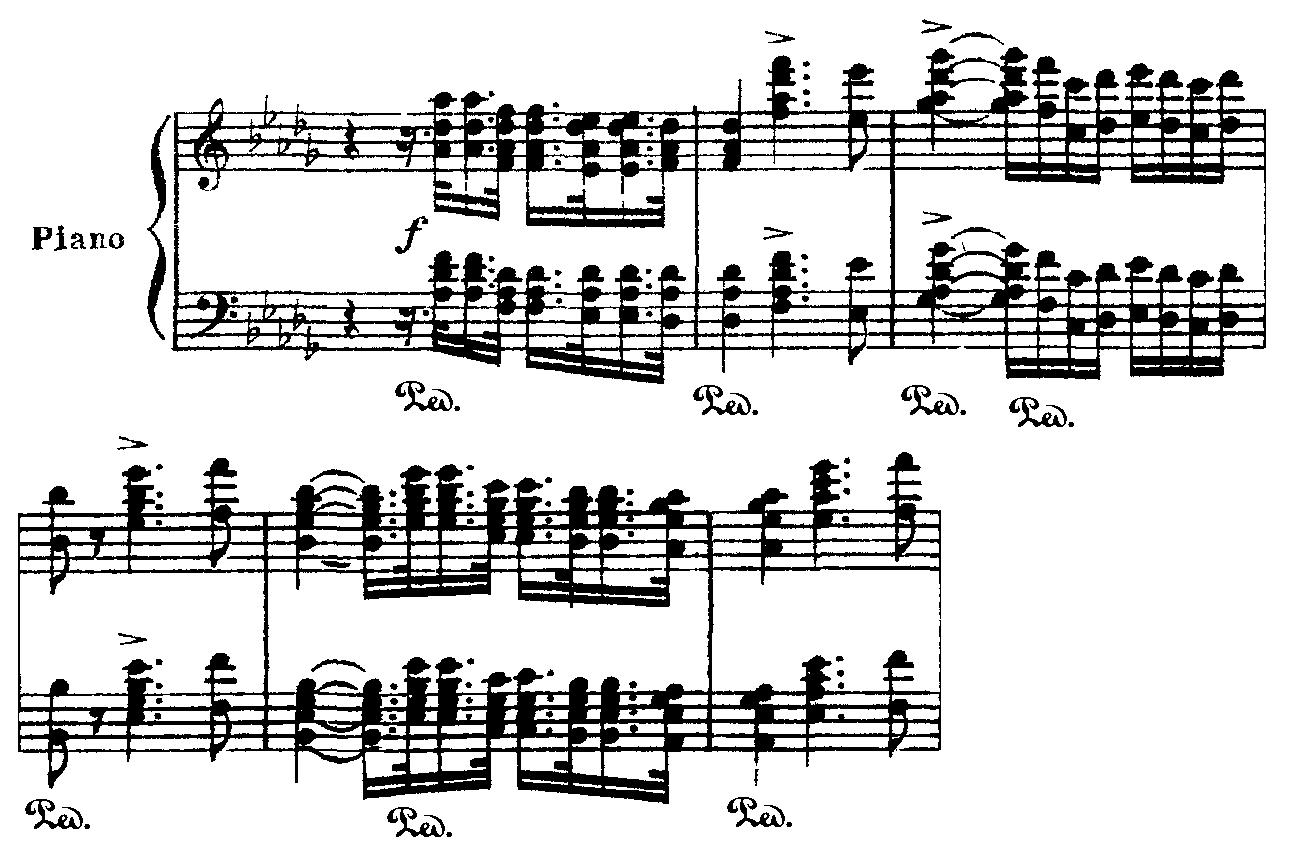

Tchaikovsky revised the concerto three times, the last in 1888, which is the version usually played. One of the most prominent differences between the original and final versions is that in the opening section, the chords played by the pianist, over which the orchestra plays the main theme, were originally written asarpeggios

A broken chord is a chord broken into a sequence of notes. A broken chord may repeat some of the notes from the chord and span one or more octaves.

An arpeggio () is a type of broken chord, in which the notes that compose a chord are played ...

. Tchaikovsky also arranged the work for two pianos in December 1874; this edition was revised in 1888.

Disagreement with Rubinstein

There is some confusion about to whom the concerto was originally dedicated. It was long thought that Tchaikovsky initially dedicated the work toNikolai Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich Tc ...

, and Michael Steinberg writes that Rubinstein's name is crossed off the autograph score. But in his Tchaikovsky biography, David Brown writes that the work was never dedicated to Rubinstein.Brown, ''Crisis Years'', 18. Tchaikovsky did hope that Rubinstein would perform the work at one of the 1875 concerts of the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. For this reason he showed the work to him and another musical friend, Nikolai Hubert, at the Moscow Conservatory on December 24, 1874/January 5, 1875, three days after finishing it. Brown writes, "This occasion has become one of the most notorious incidents in the composer's biography." Three years later, Tchaikovsky shared what happened with his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

:

I played the first movement. Not a single word, not a single remark! If you knew how stupid and intolerable is the situation of a man who cooks and sets before a friend a meal, which he proceeds to eat in silence! Oh, for one word, for friendly attack, but for God's sake one word of sympathy, even if not of praise. Rubinstein was amassing his storm, and Hubert was waiting to see what would happen, and that there would be a reason for joining one side or the other. Above all I did not want sentence on the artistic aspect. My need was for remarks about the virtuoso piano technique. R's eloquent silence was of the greatest significance. He seemed to be saying: "My friend, how can I speak of detail when the whole thing is antipathetic?" I fortified myself with patience and played through to the end. Still silence. I stood up and asked, "Well?" Then a torrent poured from Nikolay Grigoryevich's mouth, gentle at first, then more and more growing into the sound of a Jupiter Tonans. It turned out that my concerto was worthless and unplayable; passages were so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written that they were beyond rescue; the work itself was bad, vulgar; in places I had stolen from other composers; only two or three pages were worth preserving; the rest must be thrown away or completely rewritten. "Here, for instance, this—now what's all that?" (he caricatured my music on the piano) "And this? How can anyone ..." etc., etc. The chief thing I can't reproduce is the ''tone'' in which all this was uttered. In a word, a disinterested person in the room might have thought I was a maniac, a talented, senseless hack who had come to submit his rubbish to an eminent musician. Having noted my obstinate silence, Hubert was astonished and shocked that such a ticking off was being given to a man who had already written a great deal and given a course in free composition at the Conservatory, that such a contemptuous judgment without appeal was pronounced over him, such a judgment as you would not pronounce over a pupil with the slightest talent who had neglected some of his tasks—then he began to explain N.G.'s judgment, not disputing it in the least but just softening that which His Excellency had expressed with too little ceremony. I was not only astounded but outraged by the whole scene. I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition, and I no longer need lessons from anyone, especially when they are delivered so harshly and unfriendlily. I need and shall always need friendly criticism, but there was nothing resembling friendly criticism. It was indiscriminate, determined censure, delivered in such a way as to wound me to the quick. I left the room without a word and went upstairs. In my agitation and rage I could not say a thing. Presently R. enjoined me, and seeing how upset I was he asked me into one of the distant rooms. There he repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places where it would have to be completely revised, and said that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing my thing at his concert. ''"I shall not alter a single note,"'' I answered, ''"I shall publish the work exactly as it is!"'' This I did.Tchaikovsky biographer

John Warrack

John Hamilton Warrack (born 1928, in London) is an English music critic, writer on music, and oboist.

Warrack is the son of Scottish conductor and composer Guy Warrack. He was educated at Winchester College (1941-6) and then at the Royal College ...

writes that, even if Tchaikovsky were restating the facts in his favor,it was, at the very least, tactless of Rubinstein not to see how much he would upset the notoriously touchy Tchaikovsky. ... It has, moreover, been a long-enduring habit for Russians, concerned about the role of their creative work, to introduce the concept of "correctness" as a major aesthetic consideration, hence to submit to direction and criticism in a way unfamiliar in the West, from Balakirev and Stasov organizing Tchaikovsky's works according to plans of their own, to, in our own day, official intervention and the willingness of even major composers to pay attention to it.Warrack adds that Rubinstein's criticisms fell into three categories. First, he thought the writing of the solo part was bad, "and certainly there are passages which even the greatest virtuoso is glad to survive unscathed, and others in which elaborate difficulties are almost inaudible beneath the orchestra." Second, he mentioned "outside influences and unevenness of invention ... but it must be conceded that the music is uneven and that twould, like all works, seem the more uneven on a first hearing before its style had been properly understood."Warrack, 80. Third, the work probably sounded awkward to a conservative musician such as Rubinstein. While the introduction in the "wrong" key of D (for a piece supposed to be in B minor) may have taken Rubinstein aback, Warrack explains, he may have been "precipitate in condemning the work on this account or for the formal structure of all that follows."

Hans von Bülow

Brown writes that it is not known why Tchaikovsky next approached German pianistHans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, virtuoso pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for es ...

to premiere the work, although he had heard Bülow play in Moscow earlier in 1874 and been taken with his combination of intellect and passion; Bülow likewise admired Tchaikovsky's music.Steinberg, 476. Bülow was preparing to go on a tour of the United States. This meant that the concerto would be premiered half a world away from Moscow. Brown suggests that Rubinstein's comments may have deeply shaken Tchaikovsky, though he did not change the work and finished orchestrating it the following month, and that his confidence in the piece may have been so shaken that he wanted the public to hear it in a place where he would not have to personally endure any humiliation if it did not fare well. Tchaikovsky dedicated the work to Bülow, who called it "so original and noble".

The first performance of the original version took place on October 25, 1875, in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, conducted by Benjamin Johnson Lang

Benjamin Johnson Lang (December 28, 1837April 3 or 4, 1909) was an American conductor, pianist, organist, teacher and composer. He introduced a large amount of music to American audiences, including the world premiere of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ...

with Bülow as soloist. Bülow had initially engaged a different conductor, but they quarrelled, and Lang was brought in on short notice.Margaret Ruthven Lang & FamilyAccording to Alan Walker, the concerto was so popular that Bülow was obliged to repeat the Finale, a fact that Tchaikovsky found astonishing. Although the premiere was a success with the audience, the critics were not so impressed. One wrote that the piece was "hardly destined ..to become classical".

George Whitefield Chadwick

George Whitefield Chadwick (November 13, 1854 – April 4, 1931) was an American composer. Along with John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, Amy Beach, Arthur Foote, and Edward MacDowell, he was a representative composer of what is called the Se ...

, who was in the audience, recalled in a memoir years later: "They had not rehearsed much and the trombones got in wrong in the 'tutti' in the middle of the first movement, whereupon Bülow sang out in a perfectly audible voice, ''The brass may go to hell''". The work fared much better at its performance in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

on November 22, under Leopold Damrosch

Leopold Damrosch (October 22, 1832 – February 15, 1885) was a German American orchestral conductor and composer.

Biography

Damrosch was born in Posen (Poznań), Kingdom of Prussia, the son of Heinrich Damrosch. His father was Jewish and his m ...

.

Lang appeared as soloist in a complete performance of the concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on February 20, 1885, under Wilhelm Gericke

Wilhelm Gericke (April 18, 1845 – October 27, 1925) was an Austrian-born conductor and composer who worked in Vienna and Boston.

He was born in Schwanberg, Austria. Initially he trained in Graz to be a schoolmaster. This didn't work out, thoug ...

. Lang previously performed the first movement with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in March 1883, conducted by Georg Henschel, in a concert in Fitchburg, Massachusetts

Fitchburg is a city in northern Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The third-largest city in the county, its population was 41,946 at the 2020 census. Fitchburg is home to Fitchburg State University as well as 17 public and private e ...

.

The Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

n premiere took place on in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, with the Russian pianist Gustav Kross

Gustav Kross () was a Russian pianist and teacher. He is primarily remembered for being the soloist of the first, negatively-received Russian performance of Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1.

Biography

Gustav Gustavovich Kross was born in Saint ...

and the Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

conductor Eduard Nápravník

Eduard Francevič Nápravník (Russian: Эдуа́рд Фра́нцевич Напра́вник; 24 August 1839 – 10 November 1916) was a Czech conductor and composer. Nápravník settled in Russia and is best known for his leading role in Rus ...

. In Tchaikovsky's estimation, Kross reduced the work to "an atrocious cacophony". The Moscow premiere took place on , with Sergei Taneyev

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Тане́ев, ; – ) was a Russian composer, pianist, teacher of composition, music theorist and author.

Life

Taneyev was born in Vladimir, Vladimir Governorate, Russia ...

as soloist. The conductor was Rubinstein, the man who had comprehensively criticised the work less than a year earlier. Rubinstein had come to see its merits, and played the solo part many times throughout Europe. He even insisted that Tchaikovsky entrust the premiere of his Second Piano Concerto to him, and the composer would have done so had Rubinstein not died. At that time, Tchaikovsky considered rededicating the work to Taneyev, who had performed it splendidly, but ultimately the dedication went to Bülow.

Publication of original version and subsequent revisions

In 1875, Tchaikovsky published the work in its original form, but in 1876 he happily accepted advice on improving the piano writing from German pianist Edward Dannreuther, who had given the London premiere of the work, and from Russian pianist Alexander Siloti several years later. The solid chords played by the soloist at the opening of the concerto may in fact have been Siloti's idea, as they appear in the first (1875) edition as rolled chords, somewhat extended by the addition of one or sometimes two notes which made them more inconvenient to play but without significantly altering the sound of the passage. Various other slight simplifications were also incorporated into the published 1879 version. Further small revisions were undertaken for a new edition published in 1890. The American pianist Malcolm Frager unearthed and performed the original version of the concerto. In 2015, Kirill Gerstein made the world premiere recording of the 1879 version. It received anECHO Klassik The Echo Klassik, often stylized as ECHO Klassik, was Germany's major classical music award in 22 categories. The award, presented by the , was held annually, usually in October or September, separate from its parent award, the Echo Music Prize. Th ...

award in the Concerto Recording of the Year category. Based on Tchaikovsky's conducting score from his last public concert, the new critical urtext edition was published in 2015 by the Tchaikovsky Museum in Klin, tying in with Tchaikovsky's 175th anniversary and marking 140 years since the concerto's world premiere in Boston in 1875. For the recording, Gerstein was granted special pre-publication access to the new urtext edition.

Anthem of Team Russia

After Russia was banned from all major sporting competitions from 2021 to 2023 by theWorld Anti-Doping Agency

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA; french: Agence mondiale antidopage, AMA) is a foundation initiated by the International Olympic Committee based in Canada to promote, coordinate, and monitor the fight against drugs in sports. The agency's key ...

as a result of a doping scandal, those cleared to compete were allowed to represent the Russian Olympic Committee or Russian Paralympic Committee at the 2020 Summer Olympics

The , officially the and also known as , was an international multi-sport event held from 23 July to 8 August 2021 in Tokyo, Japan, with some preliminary events that began on 21 July.

Tokyo was selected as the host city during the 1 ...

and Paralympics, and at the 2022 Winter Olympics and Paralympics. Instead of the national anthem of Russia

The "State Anthem of the Russian Federation" is the national anthem of Russia. It uses the same melody as the " State Anthem of the Soviet Union", composed by Alexander Alexandrov, and new lyrics by Sergey Mikhalkov, who had collaborated wit ...

, a fragment of the concerto was used as the "Anthem of Team Russia" when athletes competing under the banner were awarded a gold medal. The introduction to the first movement had been played during the closing ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, and during the final leg of the Olympic torch relay during the Opening Ceremony of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Instrumentation

The work is scored for two flutes, twooboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

s, two clarinets in B, two bassoons, four horns Horns or The Horns may refer to:

* Plural of Horn (instrument), a group of musical instruments all with a horn-shaped bells

* The Horns (Colorado), a summit on Cheyenne Mountain

* ''Horns'' (novel), a dark fantasy novel written in 2010 by Joe Hill ...

in F, two trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s in F, three trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrate ...

s (two tenor, one bass), timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally ...

, solo piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keybo ...

, and strings.

Structure

The concerto follows the traditional form of threemovements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

:

A standard performance lasts between 30 and 36 minutes, the majority of which is taken up by the first movement.

I. Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso – Allegro con spirito

The first movement starts with a short horn theme in B minor, accompanied by orchestral chords that quickly modulate to the lyrical and passionate theme in D major. This subsidiary theme is heard three times, the last of which is preceded by a piano cadenza, and never appears again throughout the movement. The introduction ends in a subdued manner. Theexposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

* Expository writing

** Exposition (narrative)

* Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

A trade fair, also known as trade show, trade exhibition, or trade e ...

proper then begins in the concerto's tonic minor key, with a Ukrainian folk theme based on a melody that Tchaikovsky heard performed by blind lirnyks at a market in Kamianka (near Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Kyi ...

). A short transitional passage is a call and response

Call and response is a form of interaction between a speaker and an audience in which the speaker's statements ("calls") are punctuated by responses from the listeners. This form is also used in music, where it falls under the general category of ...

section on the tutti and the piano, alternating between high and low registers. The second subject group consists of two alternating themes, the first of which features some of the melodic contours from the introduction. This is answered by a smoother and more consoling second theme, played by the strings and set in the subtonic key (A major) over a pedal point, before a more turbulent reappearance of the woodwind theme, this time reinforced by driving piano arpeggios, gradually builds to a stormy climax in C minor that ends in a perfect cadence on the piano. After a short pause, a closing section, based on a variation of the consoling theme, closes the exposition in A major.Frivola-Walker 2010.

The development section

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

transforms this theme into an ominously building sequence, punctuated with snatches of the first subject material. After a flurry of piano octaves, fragments of the "plaintive" theme are revisited for the first time in E major, then for the second time in G minor. Then the piano and the strings take turns playing the theme for the third time in E major while the timpani furtively plays a tremolo on a low B until the first subject's fragments are continued.

The recapitulation features an abridged version of the first subject, working around to C minor for the transition section. In the second subject group, the consoling second theme is omitted; instead the first theme repeats, with a reappearance of the stormy climactic build previously heard in the exposition, but this time in B major. The excitement is cut short by a deceptive cadence. A brief closing section comprises G-flat major chords played by the whole orchestra and the piano. Then a piano cadenza appears, the second half of which contains subdued snatches of the second subject group's first theme in the work's original minor key. B major is restored in the coda, when the orchestra reenters with the second subject group's second theme; the tension then gradually builds, leading to a triumphant conclusion, ending with a plagal cadence.

Question of the introduction

The introduction's theme is notable for its apparent formal independence from the rest of the movement and the concerto as a whole, especially given its setting not in the work's nominal key of B minor but rather in

The introduction's theme is notable for its apparent formal independence from the rest of the movement and the concerto as a whole, especially given its setting not in the work's nominal key of B minor but rather in D major

D major (or the key of D) is a major scale based on D, consisting of the pitches D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. Its key signature has two sharps. Its relative minor is B minor and its parallel minor is D minor.

The D major scale is:

:

Ch ...

, that key's relative major. Despite its very substantial nature, this theme is only heard twice, and it never reappears at any later point in the concerto.

Russian music historian Francis Maes writes that because of its independence from the rest of the work,

For a long time, the introduction posed an enigma to analysts and critics alike. ... The key to the link between the introduction and what follows is ... Tchaikovsky's gift of hiding motivic connections behind what appears to be a flash of melodic inspiration. The opening melody comprises the most important motivic core elements for the entire work, something that is not immediately obvious, owing to its lyric quality. However, a closer analysis shows that the themes of the three movements are subtly linked. Tchaikovsky presents his structural material in a spontaneous, lyrical manner, yet with a high degree of planning and calculation.Maes adds that all the themes are tied together by a strong motivic link. These themes include the Ukrainian folk song "Oi, kriache, kriache, ta y chornenkyi voron ..." as the first theme of the first movement proper; the French ''chansonette'' "Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire" ("One must have fun, dance and laugh") in the middle section of the second movement; and a Ukrainian ''vesnianka'' "Vyidy, vyidy, Ivanku" or greeting to spring which appears as the first theme of the finale. The second theme of the finale is motivically derived from the Russian folk song "Poydu, poydu vo Tsar-Gorod" ("I'm Coming to the Capital") and also shares this motivic bond. The relationship between them has often been ascribed to chance because they were all well-known songs at the time Tchaikovsky composed the concerto. But it seems likely that he used these songs precisely because of their motivic connection. "Selecting folkloristic material," Maes writes, "went hand in hand with planning the large-scale structure of the work." All this is in line with the earlier analysis of the concerto by Tchaikovsky authority David Brown, who further suggests that Alexander Borodin's First Symphony may have given Tchaikovsky both the idea to write such an introduction and to link the work motivically as he does. Brown also identifies a four-note musical phrase ciphered from Tchaikovsky's own name and a three-note phrase likewise taken from the name of soprano Désirée Artôt, to whom the composer had been engaged some years before.

II. Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo I

The second movement, in D major, is in time. The tempo marking, "andantino semplice", lends itself to a range of interpretations; theWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

-era recording by Vladimir Horowitz

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a Russian-born American classical pianist. Considered one of the greatest pianists of al ...

and Arturo Toscanini completed the movement in under six minutes, while toward the other extreme, Lang Lang

Lang Lang (; born 14 June 1982) is a Chinese pianist who has performed with leading orchestras in China, North America, Europe, and elsewhere. Active since the 1990s, he was the first Chinese pianist to be engaged by the Berlin Philharmonic, ...

recorded the movement with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenu ...

conducted by Daniel Barenboim in eight minutes.

*Measures 1–58: Andantino semplice

*Measures 59–145: Prestissimo

*Measures 146–170: Tempo I

After a brief pizzicato introduction, the flute carries the first statement of the theme. The flute's opening four notes are A–E–F–A, while each other statement of this motif in the remainder of the movement substitutes the F for a (higher) B. The British pianist Stephen Hough

Sir Stephen Andrew Gill Hough (; born 22 November 1961) is a British-born classical pianist, composer and writer. He became an Australian citizen in 2005 and thus has dual nationality (his father was born in Australia in 1926).

Biography

Houg ...

suggests this may be an error in the published score, and that the flute should play a B. After the flute's opening statement of the melody, the piano continues and modulates to F major. After a bridge section, two cellos return with the theme in D major and the oboe continues it. The A section ends with the piano holding a high F major chord, pianissimo. The movement's B section is in D minor (the relative minor of F major) and marked "allegro vivace assai" or "prestissimo", depending on the edition. It commences with a virtuosic piano introduction before the piano assumes an accompanying role and the strings commence a new melody in D major. The B section ends with another virtuosic solo piano passage, leading into the return of the A section. In the return, the piano makes the first, now ornamented, statement of the theme. The oboe continues the theme, this time resolving it to the tonic (D major) and setting up a brief coda which finishes on another plagal cadence.

III. Allegro con fuoco – Molto meno mosso – Allegro vivo

The final movement, inrondo

The rondo is an instrumental musical form introduced in the Classical period.

Etymology

The English word ''rondo'' comes from the Italian form of the French ''rondeau'', which means "a little round".

Despite the common etymological root, rondo ...

form, starts with a very brief introduction. The A theme, in B minor, is march-like and upbeat. This melody is played by the piano until the orchestra plays a variation of it . The B theme, in D major, is more lyrical and the melody is first played by the violins, and by the piano second. A set of descending scales leads to the abridged version of the A theme.

The C theme is heard afterward, modulating through various keys, containing dotted rhythm, and a piano solo leads to:

The later measures of the A section are heard, and then the B appears, this time in E♭ major. Another set of descending scales leads to the A once more. This time, it ends with a half cadence on a secondary dominant, in which the coda starts. An urgent buildup leads to a sudden crash with F major octaves as a transition point to the last B♭ major melody played along with the orchestra, and it fuses into a dramatic and extended climactic episode, gradually building to a dominant prolongation. Then the melodies from the B theme are heard in B major. After that, the final part of the coda, marked ''allegro vivo,'' draws the work to a conclusion on a perfect authentic cadence.

Notable performances

* On March 22 .S. March 1 1878, Nikolai Rubenstein, who had initially rejected the piece before coming to see its value, finally performed the concerto as the pianist in Moscow, with Eduard Langer conducting. Rubenstein subsequently played the piece in two more cities that same year: inPalais du Trocadéro

Palais () may refer to:

* Dance hall, popularly a ''palais de danse'', in the 1950s and 1960s in the UK

* ''Palais'', French for palace

**Grand Palais, the Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

**Petit Palais, an art museum in Paris

* Palais River in t ...

(Paris), with Édouard Colonne conducting, and in St. Petersburg.

* Theodore Thomas programmed the concerto for the first concerts of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenu ...

, given on 16 and 17 October 1891. Rafael Joseffy was the soloist. Joseffy had previously performed the piece in January 1888 at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

* Wassily Sapellnikoff

Wassily Sapellnikoff (russian: Василий Львович Сапельников; tr. ''Vasily Lvovich Sapelnikov'') (17 March 1941), was a Ukrainian-born Russian pianist.

Biography

Sapellnikoff was born in Odessa. He studied at the Odessa C ...

, who played the concerto many times with Tchaikovsky himself conducting, made a record in 1926 with Aeolian Orchestra under Stanley Chapple.

* Arthur Rubinstein recorded the concerto five times: with John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

in 1932; with Dmitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos ( el, Δημήτρης Μητρόπουλος; The dates 18 February 1896 and 1 March 1896 both appear in the literature. Many of Mitropoulos's early interviews and program notes gave 18 February. In his later interviews, howe ...

in 1946; with Artur Rodzinski

Artur is a cognate to the common male given name Arthur, meaning "bear-like," which is believed to possibly be descended from the Roman surname Artorius or the Celtic bear-goddess Artio or more probably from the Celtic word ''artos'' ("bear"). O ...

live in 1946; with Carlo Maria Giulini in 1961; and with Erich Leinsdorf

Erich Leinsdorf (born Erich Landauer; February 4, 1912 – September 11, 1993) was an Austrian-born American conductor. He performed and recorded with leading orchestras and opera companies throughout the United States and Europe, earning a ...

in 1963.

* Solomon recorded the concerto thrice, most notably with Philharmonia Orchestra under Issay Dobrowen in 1949.

* Egon Petri

Egon Petri (23 March 188127 May 1962) was a Dutch pianist.

Life and career

Petri's family was Dutch. He was born a Dutch citizen but in Hanover, Germany, and grew up in Dresden, where he attended the Kreuzschule. His father, a professional vio ...

in 1937 with London Philharmonic Orchestra under Walter Goehr

Walter Goehr (; 28 May 19034 December 1960) was a German composer and conductor.

Biography

Goehr was born in Berlin, where he studied with Arnold Schoenberg and embarked on a conducting career, before being forced as a Jew to seek employment outs ...

.

* Vladimir Horowitz

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a Russian-born American classical pianist. Considered one of the greatest pianists of al ...

performed this piece as part of a World War II fundraising concert in 1943, with his father-in-law, the conductor Arturo Toscanini, conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Two performances of Horowitz playing the concerto and Toscanini conducting were eventually released on records and CDs – the live 1943 rendition, and an earlier studio recording made in 1941.

* Van Cliburn

Harvey Lavan "Van" Cliburn Jr. (; July 12, 1934February 27, 2013) was an American pianist who, at the age of 23, achieved worldwide recognition when he won the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 during the Cold W ...

won the First International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958 with this piece, surprising some people, as he was an American competing in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. He received an 8 minute standing ovation for this performance. His subsequent RCA LP recording with Kirill Kondrashin was the first classical LP to go platinum.

* Emil Gilels

Emil Grigoryevich Gilels ( Russian: Эми́ль Григо́рьевич Ги́лельс; 19 October 1916 – 14 October 1985) was a Russian pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time.

Early life and educati ...

recorded the concerto more than a dozen times, both live and in studio. The studio recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1955, and his performance in Portugal, in 1961, with the Portuguese Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Pedro de Freitas Branco, are very well regarded.

* Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter, group= ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet classical pianist. He is frequently regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his int ...

in 1962 with Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Richter also made recordings in 1954, 1957, 1958 and 1968.

* Lazar Berman recorded the concerto in studio with Berlin Philharmonic

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

under Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

in 1975 playing the revised version, and live in 1986 with Yuri Temirkanov

Yuri Khatuevich Temirkanov (russian: Ю́рий Хату́евич Темирка́нов; kbd, Темыркъан Хьэту и къуэ Юрий; born December 10, 1938) is a Russian conductor of Circassian ( Kabardian) origin.

Early life

...

playing the original version of 1875.

* Claudio Arrau

Claudio Arrau León (; February 6, 1903June 9, 1991) was a Chilean pianist known for his interpretations of a vast repertoire spanning the baroque to 20th-century composers, especially Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt and B ...

recorded the concerto twice, once in 1960 with Alceo Galliera and the Philharmonia Orchestra and again in 1979 with Sir Colin Davis and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

* Martha Argerich

Martha Argerich (; Eastern Catalan: �ɾʒəˈɾik born 5 June 1941) is an Argentine classical concert pianist. She is widely considered to be one of the greatest pianists of all time.

Early life and education

Argerich was born in Buenos A ...

recorded the concerto in 1971 with Charles Dutoit and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. She also recorded it in 1980 with Kirill Kondrashin

Kirill Petrovich Kondrashin (, ''Kirill Petrovič Kondrašin''; – 7 March 1981) was a Soviet and Russian conductor. People's Artist of the USSR (1972).

Early life

Kondrashin was born in Moscow to a family of orchestral musicians. Having spent ...

and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (german: Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, BRSO) is a German radio orchestra. Based in Munich, Germany, it is one of the city's four orchestras. The BRSO is one of two full-size symphony orchestr ...

, as well as in 1994 with Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado (; 26 June 1933 – 20 January 2014) was an Italian conductor who was one of the leading conductors of his generation. He served as music director of the La Scala opera house in Milan, principal conductor of the London Symphony ...

and the Berlin Philharmonic

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

.

* Horacio Gutiérrez's performance of this piece at the International Tchaikovsky Competition (1970) resulted in a silver medal. He later recorded with the Baltimore Symphony

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra based in Baltimore, Maryland. The Baltimore SO has its principal residence at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, where it performs more than 130 concerts a year. In 2005, it bega ...

and David Zinman

David Zinman (born July 9, 1936, in Brooklyn, NY) is an American conductor and violinist.

Education

After violin studies at Oberlin Conservatory, Zinman studied theory and composition at the University of Minnesota, earning his M.A. in 1963. H ...

.

* Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, ''Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi''; born 6 July 1937) is an internationally recognized solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. He ...

recorded the concerto in 1963 with Lorin Maazel and the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's Hall Orc ...

.

* Evgeny Kissin

Evgeny Igorevich Kissin (russian: link=no, Евге́ний И́горевич Ки́син, translit=Evgénij Ígorevič Kísin, yi, link=no, יעווגעני קיסין, translit=Yevgeni Kisin; born 10 October 1971) is a Russian concert piani ...

performed and recorded the concerto live with Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

during New Year's Eve Concert in 1988, being one of the last recordings of the maestro.

* Stanislav Ioudenitch won the gold medal at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition

The Van Cliburn International Piano Competition (The Cliburn) is an American piano competition by The Cliburn, first held in 1962 in Fort Worth, Texas and hosted by the Van Cliburn Foundation. Initially held at Texas Christian University, the c ...

in 2001 performing this concerto with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra

The Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra (FWSO) is an American symphony orchestra based in Fort Worth, Texas. The orchestra is resident at the Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass Performance Hall. In addition to its symphonic and pops concert series, the FWSO a ...

and James Conlon

James Conlon (born March 18, 1950) is an American conductor. He is currently the music director of Los Angeles Opera, principal conductor of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra, and artistic advisor to the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra.

Early ...

in the final round. His live recording of this concerto from the final round is available on the DVD ''The Cliburn: Playing on the Edge''.

* Andrej Hoteev

Andrej Ivanovich Hoteev (Андрей Иванович Хотеев/'; 2 December 1946 - 28 November 2021) was a Russian classical pianist.

Early life

Andrej Hoteev was born in Leningrad. He studied piano at the Rimsky-Korsakov Conservatory in ...

recorded 2021 the original version with Vladimir Fedoseyev and the Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra.

Notes

References

Sources

* * Brown, David, ''Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878'', (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). . * Friskin, James, "The Text of Tchaikovsky's B-flat-minor Concerto," ''Music & Letters

''Music & Letters'' is an academic journal published quarterly by Oxford University Press with a focus on musicology. The journal sponsors the Music & Letters Trust, twice-yearly cash awards of variable amounts to support research in the music fie ...

'' 50(2):246–251 (1969).

*

* Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, ''A History of Russian Music: From ''Kamarinskaya ''to'' Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). .

* Norris, Jeremy, ''The Russian Piano Concerto'' (Bloomington, 1994), Vol. 1: ''The Nineteenth Century''. .

* Poznansky, Alexander ''Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man'' (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). .

*

* Steinberg, M. ''The Concerto: A Listener's Guide'', Oxford (1998). .

* Warrack, John

John Hamilton Warrack (born 1928, in London) is an English music critic, writer on music, and oboist.

Warrack is the son of Scottish conductor and composer Guy Warrack. He was educated at Winchester College (1941-6) and then at the Royal College o ...

, ''Tchaikovsky'' (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). .

External links

* *Tchaikovsky Research

{{authority control Concertos by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

1875 compositions

1941 singles

Compositions in B-flat minor

United States National Recording Registry recordings

Olympic theme songs