Philosophy (from , )

is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about

existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval Latin ''existentia/exsistentia' ...

,

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

,

knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as Descriptive knowledge, awareness of facts or as Procedural knowledge, practical skills, and may also refer to Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called pro ...

,

values

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of something or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live (normative ethics in ethics), or to describe the significance of di ...

,

mind, and

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some sources claim the term was coined by

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

( BCE), although this theory is disputed by some.

Philosophical methods include

questioning,

critical discussion,

rational argument, and systematic presentation.

[ in .]

Historically, ''philosophy'' encompassed all bodies of knowledge and a practitioner was known as a ''

philosopher''.

["The English word "philosophy" is first attested to , meaning "knowledge, body of knowledge."

] "

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

," which began as a discipline in ancient India and Ancient Greece, encompasses

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

,

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, and

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

. For example,

Newton's 1687 ''

Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'' later became classified as a book of physics. In the 19th century, the growth of modern

research universities

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kn ...

led academic philosophy and other disciplines to

professionalize and specialize. Since then, various areas of investigation that were traditionally part of philosophy have become separate academic disciplines, and namely the

social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of so ...

such as

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

,

sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation an ...

,

linguistics

Linguistics is the science, scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure ...

, and

economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

.

Today, major subfields of academic philosophy include

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

, which is concerned with the fundamental nature of

existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval Latin ''existentia/exsistentia' ...

and

reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, r ...

;

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epis ...

, which studies the nature of

knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as Descriptive knowledge, awareness of facts or as Procedural knowledge, practical skills, and may also refer to Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called pro ...

and

belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to take ...

;

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concer ...

, which is concerned with

moral value; and

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

, which studies the

rules of inference

In the philosophy of logic, a rule of inference, inference rule or transformation rule is a logical form consisting of a function which takes premises, analyzes their syntax, and returns a conclusion (or conclusions). For example, the rule of ...

that allow one to derive

conclusions from

true

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* ...

premises

Premises are land and buildings together considered as a property. This usage arose from property owners finding the word in their title deeds, where it originally correctly meant "the aforementioned; what this document is about", from Latin ''pr ...

. Other notable subfields include

philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning ph ...

,

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ult ...

,

political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

,

aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

,

philosophy of language

In analytic philosophy, philosophy of language investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of meaning, intentionality, reference, ...

, and

philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are add ...

.

Definitions

There is wide agreement that philosophy (from the

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

, phílos: "love"; and , sophía: "wisdom") is characterized by various general features: it is a form of

rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an abi ...

inquiry, it aims to be systematic, and it tends to critically reflect on its own methods and presuppositions.

But approaches that go beyond such vague characterizations to give a more interesting or profound definition are usually controversial.

Often, they are only accepted by theorists belonging to a certain

philosophical movement

A philosophical movement refers to the phenomenon defined by a group of philosophers who share an origin or style of thought. Their ideas may develop substantially from a process of learning and communication within the group, rather than from out ...

and are revisionistic in that many presumed parts of philosophy would not deserve the title "philosophy" if they were true.

Before the modern age, the term was used in a very wide sense, which included the individual

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

s, like

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

or

mathematics, as its sub-disciplines, but the contemporary usage is more narrow.

Some approaches argue that there is a set of essential features shared by all parts of philosophy while others see only weaker family resemblances or contend that it is merely an empty blanket term.

Some definitions characterize philosophy in relation to its method, like pure reasoning. Others focus more on its topic, for example, as the study of the biggest patterns of the world as a whole or as the attempt to answer the big questions.

Both approaches have the problem that they are usually either too wide, by including non-philosophical disciplines, or too narrow, by excluding some philosophical sub-disciplines.

Many definitions of philosophy emphasize its intimate relation to science.

In this sense, philosophy is sometimes understood as a proper science in its own right. Some

naturalist approaches, for example, see philosophy as an empirical yet very abstract science that is concerned with very wide-ranging empirical patterns instead of particular observations.

Some

phenomenologists

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

, on the other hand, characterize philosophy as the science of

essence

Essence ( la, essentia) is a polysemic term, used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property or set of properties that make an entity or substance what it fundamentally is, and which it has by necessity, and without which it ...

s.

Science-based definitions usually face the problem of explaining why philosophy in its long history has not made the type of

progress as seen in other sciences.

This problem is avoided by seeing philosophy as an immature or provisional science whose subdisciplines cease to be philosophy once they have fully developed.

In this sense, philosophy is the midwife of the sciences.

Other definitions focus more on the contrast between science and philosophy. A common theme among many such definitions is that philosophy is concerned with

meaning,

understanding

Understanding is a psychological process related to an abstract or physical object, such as a person, situation, or message whereby one is able to use concepts to model that object.

Understanding is a relation between the knower and an object ...

, or the clarification of language.

According to one view, philosophy is

conceptual analysis

Philosophical analysis is any of various techniques, typically used by philosophers in the analytic tradition, in order to "break down" (i.e. analyze) philosophical issues. Arguably the most prominent of these techniques is the analysis of concep ...

, which involves finding the

necessary and sufficient conditions

In logic and mathematics, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between two statements. For example, in the conditional statement: "If then ", is necessary for , because the truth of ...

for the application of concepts.

Another defines philosophy as a linguistic therapy that aims at dispelling misunderstandings to which humans are susceptible due to the confusing structure of

natural language.

One more approach holds that the main task of philosophy is to articulate the pre-ontological understanding of the world, which acts as a

condition of possibility

In philosophy, condition of possibility (german: Bedingungen der Möglichkeit) is a concept made popular by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and is an important part of his philosophy.

A condition of possibility is a necessary framework fo ...

of

experience

Experience refers to conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these conscious processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience involv ...

.

Many other definitions of philosophy do not clearly fall into any of the aforementioned categories. An early approach already found in

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

and

Roman philosophy is that philosophy is the spiritual practice of developing one's

reasoning ability.

This practice is an expression of the philosopher's love of wisdom and has the aim of improving one's

well-being

Well-being, or wellbeing, also known as wellness, prudential value or quality of life, refers to what is intrinsically valuable relative ''to'' someone. So the well-being of a person is what is ultimately good ''for'' this person, what is in th ...

by leading a reflective life.

A closely related approach identifies the development and articulation of

worldviews

A worldview or world-view or ''Weltanschauung'' is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. A worldview can include natural ...

as the principal task of philosophy, i.e. to express how things on the grand scale hang together and which practical stance we should take towards them.

Another definition characterizes philosophy as ''

thinking

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, an ...

about thinking'' in order to emphasize its reflective nature.

Historical overview

In one general sense, philosophy is associated with

wisdom

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowle ...

, intellectual culture, and a search for knowledge. In this sense, all cultures and literate societies ask philosophical questions, such as "how are we to live" and "what is the nature of reality". A broad and impartial conception of philosophy, then, finds a reasoned inquiry into such matters as

reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, r ...

,

morality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of co ...

, and life in all world civilizations.

Western philosophy

Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

is the philosophical tradition of the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. , dating back to

pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

thinkers who were active in 6th-century

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

(BCE), such as

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

( BCE) and

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

( BCE) who practiced a 'love of wisdom' ()

and were also termed 'students of nature' ().

Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

can be divided into three eras:

#

Ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

(

Greco-Roman).

#

Medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, ...

(referring to Christian European thought).

#

Modern philosophy

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school (and thus should not be confused with ''Modernism''), although there are certain assumptions common to much of i ...

(beginning in the 17th century).

Ancient era

While our knowledge of the ancient era begins with

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

in the 6th century BCE, little is known about the philosophers who came before

Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

(commonly known as

the pre-Socratics). The ancient era was dominated by

Greek philosophical schools. Most notable among the schools influenced by Socrates' teachings were

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, who founded the

Platonic Academy

The Academy (Ancient Greek: Ἀκαδημία) was founded by Plato in c. 387 BC in Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years (367–347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic p ...

, and his student

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, who founded the

Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristo ...

. Other ancient philosophical traditions influenced by Socrates included

Cynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

,

Cyrenaicism,

Stoicism, and

Academic Skepticism

Academic skepticism refers to the skeptical period of ancient Platonism dating from around 266 BCE, when Arcesilaus became scholarch of the Platonic Academy, until around 90 BCE, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism, although indi ...

. Two other traditions were influenced by Socrates' contemporary,

Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

:

Pyrrhonism and

Epicureanism. Important topics covered by the Greeks included

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

(with competing theories such as

atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

and

monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

),

cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

, the nature of the well-lived life (''

eudaimonia''), the

possibility of knowledge, and the nature of reason (

logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

). With the rise of the

Roman empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, Greek philosophy was increasingly discussed in

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

by

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

such as

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

and

Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

(see

Roman philosophy).

Medieval era

Medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, ...

(5th–16th centuries) took place during the period following the fall of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

and was dominated by the rise of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

; it hence reflects

Judeo-Christian theological concerns while also retaining a continuity with Greco-Roman thought. Problems such as the existence and nature of

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, the nature of

faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

and reason, metaphysics, and the

problem of evil

The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,The Problem of Evil, Michael TooleyThe Internet Encycl ...

were discussed in this period. Some key medieval thinkers include

St. Augustine,

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

,

Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

,

Anselm and

Roger Bacon. Philosophy for these thinkers was viewed as an aid to

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

(), and hence they sought to align their philosophy with their interpretation of sacred scripture. This period saw the development of

scholasticism, a text critical method developed in

medieval universities based on close reading and disputation on key texts. The

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

period saw increasing focus on classic Greco-Roman thought and on a robust

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and Agency (philosophy), agency of Human, human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical in ...

.

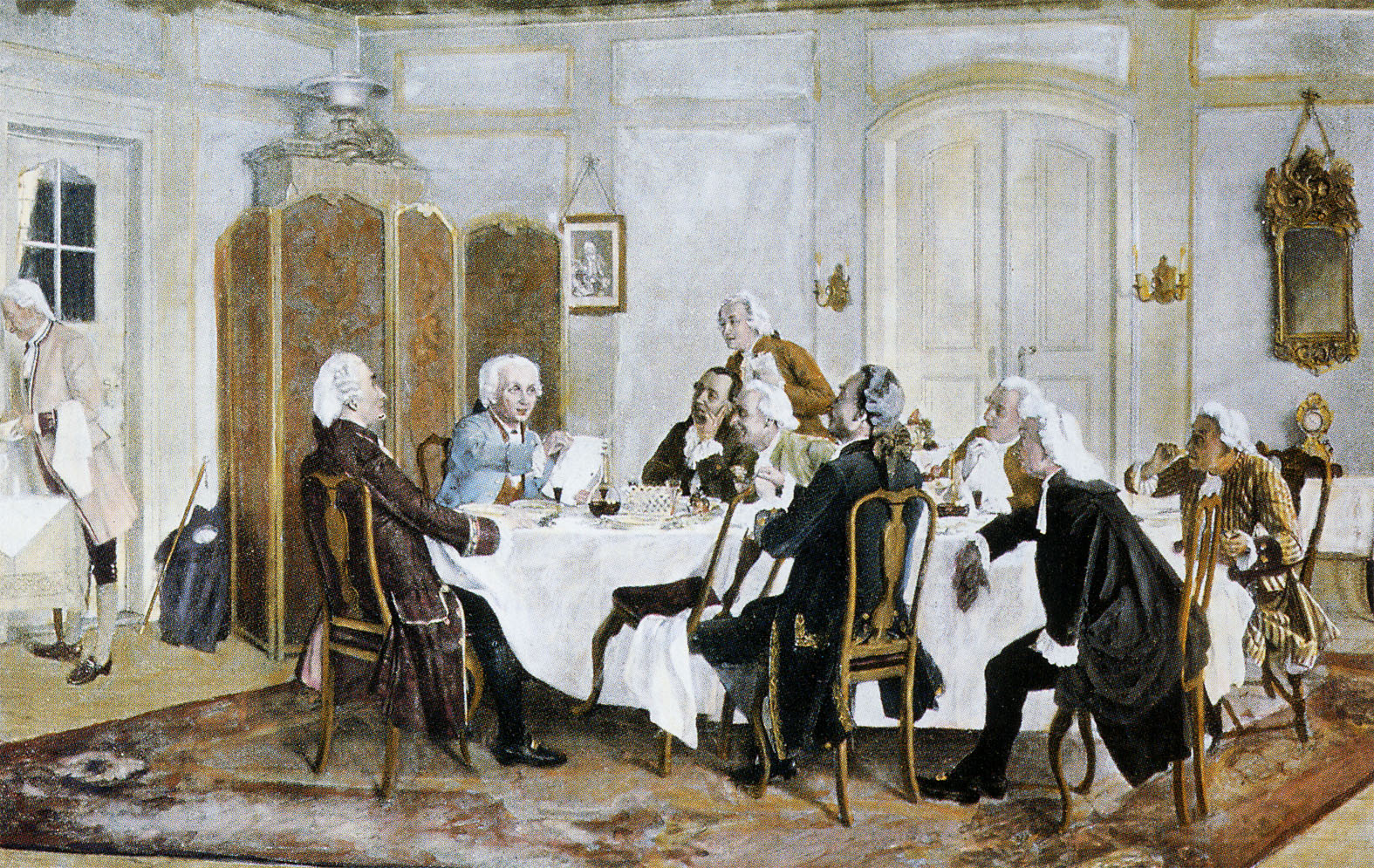

Modern era

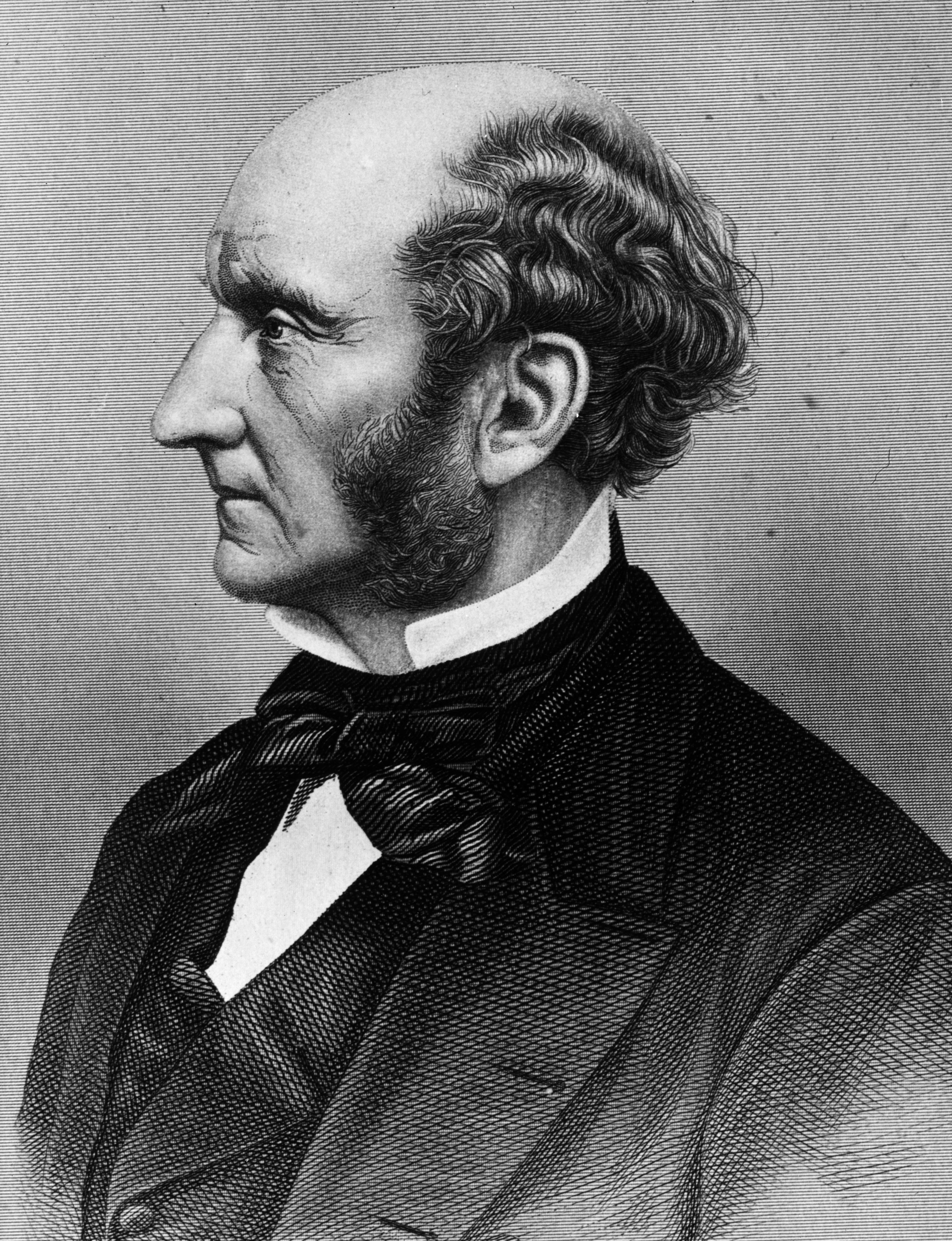

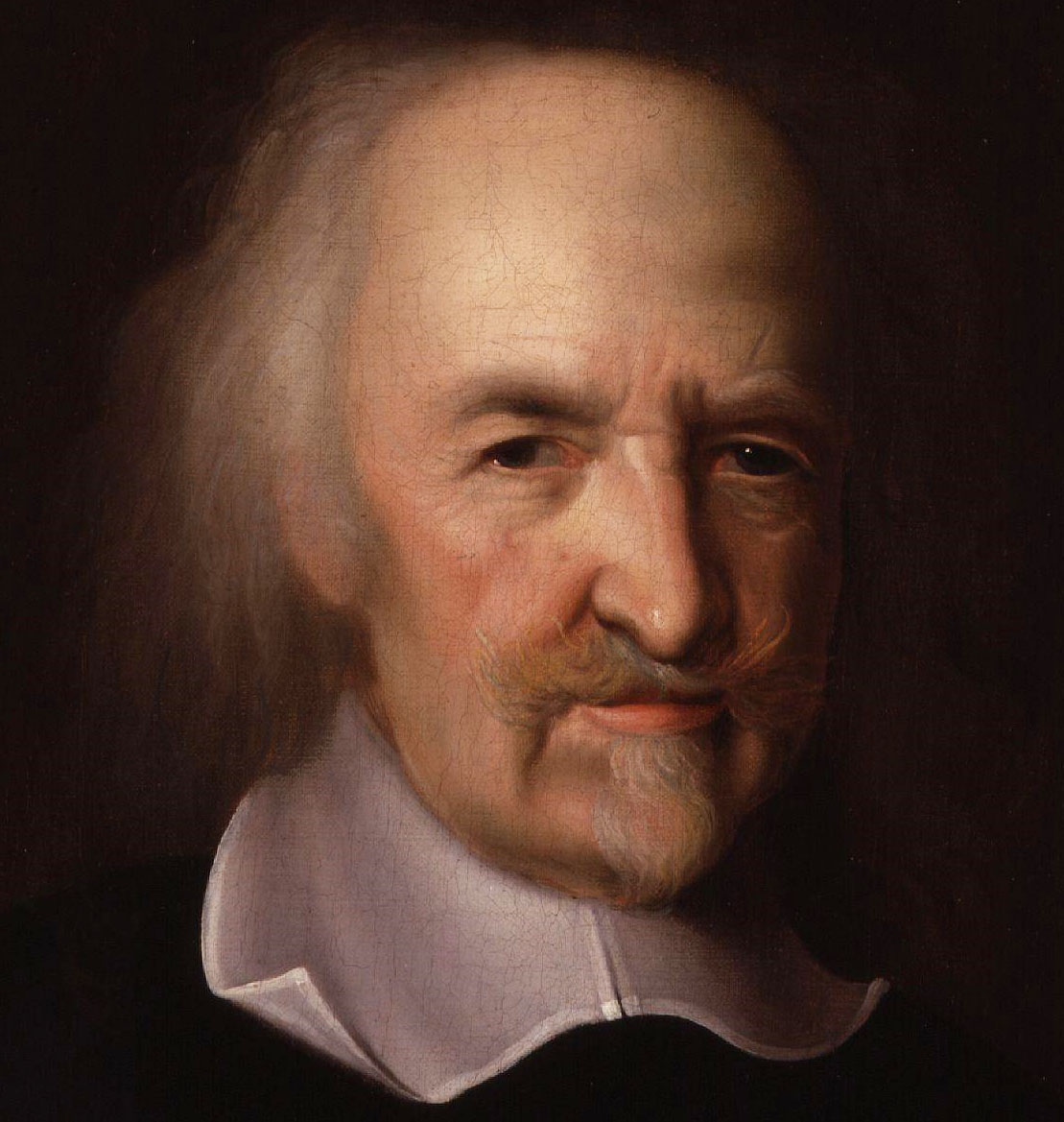

Early modern philosophy

Early modern philosophy (also classical modern philosophy)Richard Schacht, ''Classical Modern Philosophers: Descartes to Kant'', Routledge, 2013, p. 1: "Seven men have come to stand out from all of their counterparts in what has come to be known ...

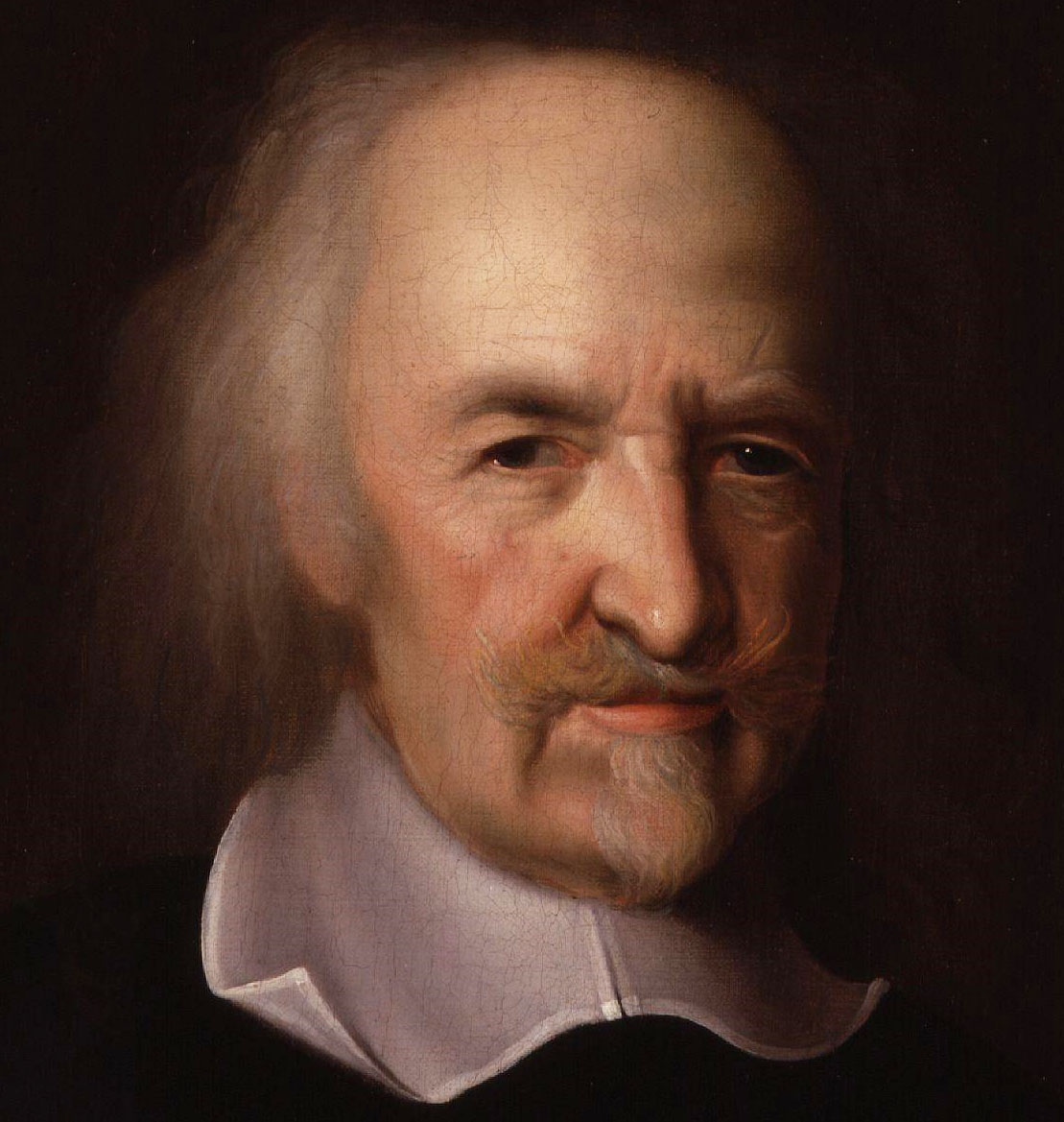

in the Western world begins with thinkers such as

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

and

René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

(1596–1650).

Following the rise of natural science,

modern philosophy

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school (and thus should not be confused with ''Modernism''), although there are certain assumptions common to much of i ...

was concerned with developing a secular and rational foundation for knowledge and moved away from traditional structures of authority such as religion, scholastic thought and the Church. Major modern philosophers include

Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

,

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ma ...

,

Locke,

Berkeley,

Hume, and

Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

.

19th-century philosophy (sometimes called

late modern philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ...

) was influenced by the wider 18th-century movement termed "

the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

", and includes figures such as

Hegel, a key figure in

German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

;

Kierkegaard, who developed the foundations for

existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

;

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, representative of the

great man theory;

Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his car ...

, a famed anti-Christian;

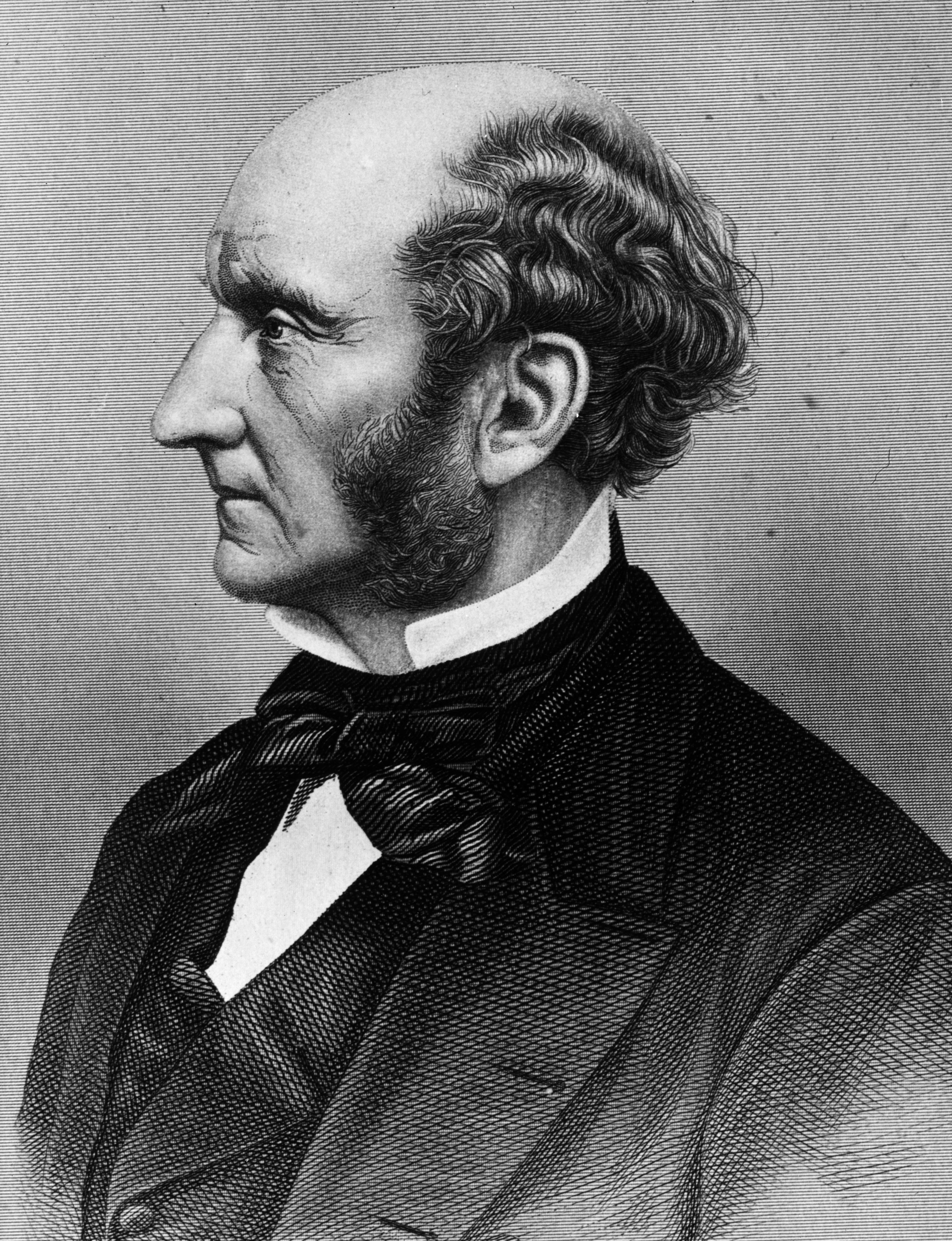

John Stuart Mill, who promoted

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

;

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, who developed the foundations for

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

; and the American

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

. The 20th century saw the split between

analytic philosophy and

continental philosophy, as well as philosophical trends such as

phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

,

existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

,

logical positivism,

pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

and the

linguistic turn

The linguistic turn was a major development in Western philosophy during the early 20th century, the most important characteristic of which is the focusing of philosophy and the other humanities primarily on the relations between language, langua ...

(see

Contemporary philosophy).

Middle Eastern philosophy

Pre-Islamic philosophy

The regions of the

Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

,

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

are home to the earliest known philosophical wisdom literature.

According to the

assyriologist

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

Marc Van de Mieroop

Marc Van de Mieroop (b. 22 October 1956) is a noted Belgians, Belgian Assyriology, Assyriologist and Egyptology, Egyptologist who has been full professor of Ancient Near Eastern history at Columbia University since 1996.

Biography

Born in Bel ...

,

Babylonian philosophy was a highly developed system of thought with a unique approach to knowledge and a focus on writing,

lexicography

Lexicography is the study of lexicons, and is divided into two separate academic disciplines. It is the art of compiling dictionaries.

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoreti ...

, divination, and law. It was also a

bilingual intellectual culture, based on

Sumerian and

Akkadian.

Early

Wisdom literature

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it w ...

from the Fertile Crescent was a genre that sought to instruct people on ethical action, practical living, and virtue through stories and proverbs. In

Ancient Egypt, these texts were known as ''

sebayt Sebayt (Egyptian '' sbꜣyt'', Coptic ⲥⲃⲱ "instruction, teaching") is the ancient Egyptian term for a genre of pharaonic literature. ''sbꜣyt'' literally means "teachings" or "instructions" and refers to formally written ethical teachings f ...

'' ('teachings'), and they are central to our understandings of

Ancient Egyptian philosophy. The most well known of these texts is ''

The Maxims of Ptahhotep

''The Maxims of Ptahhotep'' or ''Instruction of Ptahhotep'' is an ancient Egyptian literary composition composed by the Vizier Ptahhotep around 2375–2350 BC, during the rule of King Djedkare Isesi of the Fifth Dynasty. The text was discovered ...

.'' Theology and cosmology were central concerns in Egyptian thought. Perhaps the earliest form of a

monotheistic theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

also emerged in Egypt, with the rise of the

Amarna theology (or Atenism) of

Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth D ...

(14th century BCE), which held that the solar creation deity

Aten

Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn ( egy, jtn, ''reconstructed'' ) was the focus of Atenism, the religious system established in ancient Egypt by the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect o ...

was the only god. This has been described as a "monotheistic revolution" by

egyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religiou ...

Jan Assmann

Jan Assmann (born Johann Christoph Assmann; born 7 July 1938) is a German Egyptologist.

Life and works

Assmann studied Egyptology and classical archaeology in Munich, Heidelberg, Paris, and Göttingen. In 1966–67, he was a fellow of the German ...

, though it also drew on previous developments in Egyptian thought, particularly the "New Solar Theology" based around

Amun-Ra

Amun (; also ''Amon'', ''Ammon'', ''Amen''; egy, jmn, reconstructed as ( Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian) → (later Middle Egyptian) → ( Late Egyptian), cop, Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ, Amoun) romanized: ʾmn) was a major ancient Egypt ...

.

These theological developments also influenced the post-Amarna

Ramesside

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth century BC and the eleventh century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties of Egypt. Radioca ...

theology, which retained a focus on a single creative solar deity (though without outright rejection of other gods, which are now seen as manifestations of the main solar deity). This period also saw the development of the concept of the

''ba'' (soul) and its relation to god.

and

Christian philosophy

Christian philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to the religion of Christianity.

Christian philosophy emerged with the aim of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational explanations w ...

are religious-philosophical traditions that developed both in the Middle East and in Europe, which both share certain early Judaic texts (mainly the

Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

'' Geonim

''Geonim'' ( he, גאונים; ; also transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura and Pumbedita, in the Abbasid Caliphate, and were the generally accepted spiritual leaders of ...

of the

Talmudic Academies in Babylonia and

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

engaged with Greek and Islamic philosophy. Later Jewish philosophy came under strong Western intellectual influences and includes the works of

Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or ' ...

who ushered in the

Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

(the Jewish Enlightenment),

Jewish existentialism, and

Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous sear ...

.

The various traditions of

Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

, which were influenced by both Greek and Abrahamic currents, originated around the first century and emphasized spiritual knowledge (''

gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge ( γνῶσις, ''gnōsis'', f.). The term was used among various Hellenistic religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world. It is best known for its implication within Gnosticism, where it ...

'').

Pre-Islamic

Iranian philosophy

Iranian philosophy ( Persian: فلسفه ایرانی) or Persian philosophy can be traced back as far as to Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts which originated in ancient Indo-Iranian roots and were considerably influenced by Zar ...

begins with the work of

Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label= Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism. He is ...

, one of the first promoters of

monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfo ...

and of the

dualism between good and evil. This dualistic cosmogony influenced later Iranian developments such as

Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian Empire, Parthian ...

,

Mazdakism, and

Zurvanism

Zurvanism is a fatalistic religious movement of Zoroastrianism in which the divinity Zurvan is a first principle (primordial creator deity) who engendered equal-but-opposite twins, Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. Zurvanism is also known as "Zu ...

.

Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic, ...

is the philosophical work originating in the

Islamic tradition and is mostly done in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. It draws from the religion of Islam as well as from Greco-Roman philosophy. After the

Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

, the

translation movement (mid-eighth to the late tenth century) resulted in the works of Greek philosophy becoming available in Arabic.

Early Islamic philosophy developed the Greek philosophical traditions in new innovative directions. This intellectual work inaugurated what is known as the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

. The two main currents of early Islamic thought are

Kalam

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

, which focuses on

Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Batin ...

, and

Falsafa

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic, ...

, which was based on

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the so ...

and

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some i ...

. The work of Aristotle was very influential among philosophers such as

Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(9th century),

Avicenna (980 – June 1037), and

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

(12th century). Others such as

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

were highly critical of the methods of the Islamic Aristotelians and saw their metaphysical ideas as heretical. Islamic thinkers like

Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pri ...

and

Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

also developed a

scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

, experimental medicine, a theory of optics, and a legal philosophy.

Ibn Khaldun was an influential thinker in

philosophy of history.

Islamic thought also deeply influenced European intellectual developments, especially through the commentaries of Averroes on Aristotle. The

Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire ( 1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastatio ...

and the

destruction of Baghdad in 1258 are often seen as marking the end of the Golden Age. Several schools of Islamic philosophy continued to flourish after the Golden Age, however, and include currents such as

Illuminationist philosophy

Illuminationism (Persian حكمت اشراق ''hekmat-e eshrāq'', Arabic: حكمة الإشراق ''ḥikmat al-ishrāq'', both meaning "Wisdom of the Rising Light"), also known as ''Ishrāqiyyun'' or simply ''Ishrāqi'' (Persian اشراق, Arab ...

,

Sufi philosophy

Sufi philosophy includes the schools of thought unique to Sufism, the mystical tradition within Islam, also termed as ''Tasawwuf'' or ''Faqr'' according to its adherents. Sufism and its philosophical tradition may be associated with both Sunni a ...

, and

Transcendent theosophy

Transcendent theosophy or al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah (حكمت متعاليه), the doctrine and philosophy developed by Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra (d.1635 CE), is one of two main disciplines of Islamic philosophy that are currently live an ...

.

The 19th- and 20th-century

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

saw the ''

Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, Leb ...

'' movement (literally meaning 'The Awakening'; also known as the 'Arab Renaissance'), which had a considerable influence on

contemporary Islamic philosophy

Contemporary Islamic philosophy revives some of the trends of medieval Islamic philosophy, notably the tension between Mutazilite and Asharite views of ethics in science and law, and the duty of Muslims and role of Islam in the sociology o ...

.

Eastern philosophy

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Veda ...

( sa, , lit=point of view', 'perspective) refers to the diverse philosophical traditions that emerged since the ancient times on the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

. Indian philosophy chiefly considers epistemology, theories of consciousness and theories of mind, and the physical properties of reality. Indian philosophical traditions share various key concepts and ideas, which are defined in different ways and accepted or rejected by the different traditions. These include concepts such as

''dhárma'', ''

karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

'', ''

pramāṇa,'' ''

duḥkha

''Duḥkha'' (; Sanskrit: दुःख; Pāli: ''dukkha''), commonly translated as "suffering", "pain," or "unhappiness," is an important concept in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism. Its meaning depends on the context, and may refer more specif ...

,

saṃsāra'' and ''

mokṣa.''

Some of the earliest surviving Indian philosophical texts are the

Upanishads

The Upanishads (; sa, उपनिषद् ) are late Vedic Sanskrit texts that supplied the basis of later Hindu philosophy.Wendy Doniger (1990), ''Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism'', 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, , ...

of the

later Vedic period

Later may refer to:

* Future, the time after the present

Television

* ''Later'' (talk show), a 1988–2001 American talk show

* '' Later... with Jools Holland'', a British music programme since 1992

* ''The Life and Times of Eddie Roberts'', or ...

(1000–500 BCE), which are considered to preserve the ideas of

Brahmanism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

. Indian philosophical traditions are commonly grouped according to their relationship to the Vedas and the ideas contained in them.

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

and

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

originated at the end of the

Vedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ca. 1300–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, betwe ...

, while the various traditions grouped under

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

mostly emerged after the Vedic period as independent traditions. Hindus generally classify Indian philosophical traditions as either orthodox (

''āstika'') or heterodox (''nāstika'') depending on whether they accept the authority of the

Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

and the theories of ''

brahman

In Hinduism, ''Brahman'' ( sa, ब्रह्मन्) connotes the highest universal principle, the ultimate reality in the universe.P. T. Raju (2006), ''Idealistic Thought of India'', Routledge, , page 426 and Conclusion chapter part X ...

'' and

''ātman'' found therein.

The schools which align themselves with the thought of the Upanishads, the so-called "orthodox" or "

Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

" traditions, are often classified into six ''

darśanas'' or philosophies:

Sānkhya,

Yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consci ...

,

Nyāya,

Vaisheshika

Vaisheshika or Vaiśeṣika ( sa, वैशेषिक) is one of the six schools of Indian philosophy (Vedic systems) from ancient India. In its early stages, the Vaiśeṣika was an independent philosophy with its own metaphysics, epistemolog ...

,

Mimāmsā and

Vedānta

''Vedanta'' (; sa, वेदान्त, ), also ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six (''āstika'') schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, t ...

.

The doctrines of the Vedas and Upanishads were interpreted differently by these six schools of

Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy encompasses the philosophies, world views and teachings of Hinduism that emerged in Ancient India which include six systems ('' shad-darśana'') – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta.Andrew Nicholson ( ...

, with varying degrees of overlap. They represent a "collection of philosophical views that share a textual connection", according to Chadha (2015). They also reflect a tolerance for a diversity of philosophical interpretations within Hinduism while sharing the same foundation.

Hindu philosophers of the six orthodox schools developed systems of epistemology (''

pramana

''Pramana'' (Sanskrit: प्रमाण, ) literally means "proof" and "means of knowledge".[guṇa

( sa, गुण) is a concept in Hinduism, Jainism and Sikhism, which can be translated as "quality, peculiarity, attribute, property".][hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. Hermeneutics is more than interpretative principles or methods used when immediate ...](_b ...<br></span></div>''), <div class=)

, and

soteriology

Soteriology (; el, σωτηρία ' "salvation" from σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many religion ...

within the framework of the Vedic knowledge, while presenting a diverse collection of interpretations.

The commonly named six orthodox schools were the competing philosophical traditions of what has been called the "Hindu synthesis" of

classical Hinduism.

There are also other schools of thought which are often seen as "Hindu", though not necessarily orthodox (since they may accept different scriptures as normative, such as the

Shaiva Agamas and Tantras), these include different schools of

Shavism such as

Pashupata

Pashupata Shaivism (, sa, पाशुपत) is the oldest of the major Shaivite Hindu schools. The mainstream which follows Vedic Pasupata penance are 'Maha Pasupatas' and the schism of 'Lakula Pasupata' of Lakulisa.

There is a debate about ...

,

Shaiva Siddhanta

Shaiva Siddhanta () (Tamil: சைவ சித்தாந்தம் "Caiva cittāntam") is a form of Shaivism that propounds a dualistic philosophy where the ultimate and ideal goal of a being is to become an enlightened soul through Shiv ...

,

non-dual tantric Shavism (i.e. Trika, Kaula, etc.).

The "Hindu" and "Orthodox" traditions are often contrasted with the "unorthodox" traditions (''nāstika,'' literally "those who reject"), though this is a label that is not used by the "unorthodox" schools themselves. These traditions reject the Vedas as authoritative and often reject major concepts and ideas that are widely accepted by the orthodox schools (such as ''Ātman'', ''Brahman'', and

''Īśvara'').

These unorthodox schools include Jainism (accepts ''ātman'' but rejects ''Īśvara,'' Vedas and ''Brahman''), Buddhism (rejects all orthodox concepts except rebirth and karma),

Cārvāka (materialists who reject even rebirth and karma) and

Ājīvika

''Ajivika'' (IAST: ) is one of the Āstika and nāstika, ''nāstika'' or "heterodox" schools of Indian philosophy.Natalia Isaeva (1993), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, , pages 20-23James Lochtefeld, "Ajivik ...

(known for their doctrine of fate).

<

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system found in Jainism. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence, the living, consciou ...

is one of the only two surviving "unorthodox" traditions (along with Buddhism). It generally accepts the concept of a permanent soul (''

jiva

''Jiva'' ( sa, जीव, IAST: ) is a living being or any entity imbued with a life force in Hinduism and Jainism. The word itself originates from the Sanskrit verb-root ''jīv'', which translates as 'to breathe' or 'to live'. The ''jiva'', a ...

'') as one of the five ''

astikayas'' (eternal, infinite categories that make up the substance of existence). The other four being

''dhárma'', ''

adharma

Adharma is the Sanskrit antonym of dharma. It means "that which is not in accord with the dharma". Connotations include betrayal, discord, disharmony, unnaturalness, wrongness, evil, immorality, unrighteousness, wickedness, and vice..In Indi ...

'', ''

ākāśa'' ('space'), and ''

pudgala

In Jainism, Pudgala (or ') is one of the six Dravyas, or aspects of reality that fabricate the world we live in. The six ''dravya''s include the jiva and the fivefold divisions of ajiva (non-living) category: ''dharma'' (motion), ''adharma'' ( ...

'' ('matter'). Jain thought holds that all existence is cyclic, eternal and uncreated.

Some of the most important elements of Jain philosophy are the

Jain theory of karma, the doctrine of nonviolence (

ahiṃsā

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India – F ...

) and the theory of "many-sidedness" or

Anēkāntavāda. The ''

Tattvartha Sutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature '' ''artha">nowiki/>''artha''.html" ;"title="artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ...

'' is the earliest known, most comprehensive and authoritative compilation of Jain philosophy.

Major European Quantum Physicists, including Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Albert Einstein, & Niels Bohr credit the Vedas with giving them the ideas for their experiments.

Buddhist philosophy

Buddhist philosophy begins with the thought of

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

(

fl. between 6th and 4th century BCE) and is preserved in the

early Buddhist texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

. It originated in the Indian region of

Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

and later spread to the rest of the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

,

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

,

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

,

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

. In these regions, Buddhist thought developed into different philosophical traditions which used various languages (like

Tibetan,

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and

Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Buddh ...

). As such, Buddhist philosophy is a

trans-cultural and international phenomenon.

The dominant Buddhist philosophical traditions in

East Asian nations are mainly based on Indian

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

Buddhism. The

philosophy of the Theravada school is dominant in

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

n countries like

Sri Lanka,

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

.

Because

ignorance

Ignorance is a lack of knowledge and understanding. The word "ignorant" is an adjective that describes a person in the state of being unaware, or even cognitive dissonance and other cognitive relation, and can describe individuals who are unaware ...

to the true nature of things is considered one of the roots of suffering (''

dukkha''), Buddhist philosophy is concerned with epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and psychology. Buddhist philosophical texts must also be understood within the context of

meditative practices which are supposed to bring about certain cognitive shifts. Key innovative concepts include the

Four Noble Truths as an analysis of ''dukkha'',

''anicca'' (impermanence), and ''

anatta'' (non-self).

After the death of the Buddha, various groups began to systematize his main teachings, eventually developing comprehensive philosophical systems termed ''

Abhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the f ...

''. Following the Abhidharma schools, Indian

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

philosophers such as

Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

and

Vasubandhu

Vasubandhu (; Tibetan: དབྱིག་གཉེན་ ; fl. 4th to 5th century CE) was an influential Buddhist monk and scholar from ''Puruṣapura'' in ancient India, modern day Peshawar, Pakistan. He was a philosopher who wrote commentary ...

developed the theories of ''

śūnyatā

''Śūnyatā'' ( sa, शून्यता, śūnyatā; pi, suññatā; ), translated most often as ''emptiness'', ''vacuity'', and sometimes ''voidness'', is an Indian philosophical concept. Within Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and other ...

'' ('emptiness of all phenomena') and

''vijñapti-matra'' ('appearance only'), a form of phenomenology or

transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that dese ...

. The

Dignāga

Dignāga (a.k.a. ''Diṅnāga'', c. 480 – c. 540 CE) was an Indian Buddhist scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian logic (''hetu vidyā''). Dignāga's work laid the groundwork for the development of deductive logic in India and ...

school of ''

pramāṇa'' ('means of knowledge') promoted a sophisticated form of

Buddhist epistemology.

There were numerous schools, sub-schools, and traditions of Buddhist philosophy in ancient and medieval India. According to Oxford professor of Buddhist philosophy

Jan Westerhoff

Jan Christoph Westerhoff is a German philosopher and orientalist with specific interests in metaphysics and the philosophy of language. He is currently Professor (highest academic rank), Professor of Buddhist Philosophy in the Faculty of Theology a ...

, the major Indian schools from 300 BCE to 1000 CE were: the

Mahāsāṃghika

The Mahāsāṃghika ( Brahmi: 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀲𑀸𑀁𑀖𑀺𑀓, "of the Great Sangha", ) was one of the early Buddhist schools. Interest in the origins of the Mahāsāṃghika school lies in the fact that their Vinaya recension appears in ...

tradition (now extinct), the

Sthavira schools (such as

Sarvāstivāda

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy ...

,

Vibhajyavāda

Vibhajyavāda (Sanskrit; Pāli: ''Vibhajjavāda''; ) is a term applied generally to groups of early Buddhists belonging to the Sthavira Nikaya. These various groups are known to have rejected Sarvāstivāda doctrines (especially the doctrine of ...

and

Pudgalavāda) and the

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

schools. Many of these traditions were also studied in other regions, like Central Asia and China, having been brought there by Buddhist missionaries.

After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the

Tibetan Buddhist