Philip VI of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the

In 1328, Philip VI's first cousin King Charles IV died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King

In 1328, Philip VI's first cousin King Charles IV died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King  During the period in which Charles IV's widow was waiting to deliver her child, Philip VI rose to the regency with support of the French magnates, following the pattern set up by his cousin King Philip V who succeeded the throne over his niece

During the period in which Charles IV's widow was waiting to deliver her child, Philip VI rose to the regency with support of the French magnates, following the pattern set up by his cousin King Philip V who succeeded the throne over his niece

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the Black Death struck France and in the next few years killed one-third of the population, including Queen Joan. The resulting labour shortage caused inflation to soar, and the king attempted to fix prices, further destabilising the country. His second marriage to his son's betrothed Blanche of Navarre alienated his son and many nobles from the king.

Philip's last major achievement was the acquisition of the

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the Black Death struck France and in the next few years killed one-third of the population, including Queen Joan. The resulting labour shortage caused inflation to soar, and the king attempted to fix prices, further destabilising the country. His second marriage to his son's betrothed Blanche of Navarre alienated his son and many nobles from the king.

Philip's last major achievement was the acquisition of the

House of Valois

The Capetian house of Valois ( , also , ) was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet (or "Direct Capetians") to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the f ...

, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350.

Philip's reign was dominated by the consequences of a succession dispute. When King Charles IV of France died in 1328, the nearest male relative was his nephew King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

, but the French nobility preferred Charles's paternal cousin Philip. At first, Edward seemed to accept Philip's succession, but he pressed his claim to the throne of France after a series of disagreements with Philip. The result was the beginning of the Hundred Years' War in 1337.

After initial successes at sea, Philip's navy was annihilated at the Battle of Sluys

The Battle of Sluys (; ), also called the Battle of l'Écluse, was a naval battle fought on 24 June 1340 between England and France. It took place in the roadstead of the port of Sluys (French ''Écluse''), on a since silted-up inlet between ...

in 1340, ensuring that the war would occur on the continent. The English took another decisive advantage at the Battle of Crécy (1346), while the Black Death struck France, further destabilising the country.

In 1349, King Philip VI bought the Province of Dauphiné from its ruined ruler the Dauphin Humbert II

Dauphin (french: "dolphin", links=no, plural ''dauphins'') may refer to:

Noble and royal title

* Dauphin of Auvergne

* Dauphin of France, heir apparent to the French crown

* Dauphin of Viennois

People

* Charles Dauphin (c. 1620–1677), French p ...

and entrusted the government of this province to his grandson Prince Charles. Philip VI died in 1350 and was succeeded by his son King John II, the Good.

Early life

Little is recorded about Philip's childhood and youth, in large part because he was of minor royal birth. Philip's fatherCharles, Count of Valois

Charles of Valois (12 March 1270 – 16 December 1325), the fourth son of King Philip III of France and Isabella of Aragon, was a member of the House of Capet and founder of the House of Valois, whose rule over France would start in 1328 ...

, the younger brother of King Philip IV of France, had striven throughout his life to gain the throne for himself but was never successful. He died in 1325, leaving his eldest son Philip as heir to the counties of Anjou, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, and Valois.Elizabeth Hallam and Judith Everard, ''Capetian France 987-1328'', 2nd edition, (Pearson Education Limited, 2001), 366.

Accession to the throne

In 1328, Philip VI's first cousin King Charles IV died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King

In 1328, Philip VI's first cousin King Charles IV died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

, who was the son of Charles's sister Isabella of France

Isabella of France ( – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France (), was Queen of England as the wife of King Edward II, and regent of England from 1327 until 1330. She was the youngest surviving child and only surviving ...

, and Charles IV's closest male relative. The Estates General had decided 20 years earlier that women could not inherit the throne of France. The question arose as to whether Isabella should have been able to transmit a claim that she herself did not possess.Jonathan Sumption

Jonathan Philip Chadwick Sumption, Lord Sumption, (born 9 December 1948), is a British author, medieval historian and former senior judge who sat on the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom between 2012 and 2018. Sumption was sworn in as a Jus ...

, ''The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle'', Vol. I, (Faber & Faber, 1990), 106-107. The assemblies of the French barons and prelates and the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

decided that males who derive their right to inheritance through their mother should be excluded according to Salic law. As Philip was the eldest grandson of King Philip III of France, through the male line, he became regent instead of Edward, who was a matrilineal grandson of King Philip IV and great-grandson of King Philip III.

During the period in which Charles IV's widow was waiting to deliver her child, Philip VI rose to the regency with support of the French magnates, following the pattern set up by his cousin King Philip V who succeeded the throne over his niece

During the period in which Charles IV's widow was waiting to deliver her child, Philip VI rose to the regency with support of the French magnates, following the pattern set up by his cousin King Philip V who succeeded the throne over his niece Joan II of Navarre

Joan II (french: Jeanne; 28 January 1312 – 6 October 1349) was Queen of Navarre from 1328 until her death. She was the only surviving child of Louis X of France, King of France and Navarre, and Margaret of Burgundy. Joan's paternity was dubiou ...

. He formally held the regency from 9 February 1328 until 1 April, when Jeanne of Évreux gave birth to a daughter named Blanche of France, Duchess of Orléans. Upon this birth, Philip was named king and crowned at the Cathedral in Reims on 29 May 1328. After his elevation to the throne, Philip sent the Abbot of Fécamp

Fécamp () is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France.

Geography

Fécamp is situated in the valley of the river Valmont, at the heart of the Pays de Caux, on the Alabaster Coast. It is aroun ...

, Pierre Roger, to summon Edward III of England to pay homage for the duchy of Aquitaine and Gascony.Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle'', 109-110. After a subsequent second summons from Philip, Edward finally arrived at the Cathedral of Amiens on 6 June 1329 and worded his vows in such a way to cause more disputes in later years.

The dynastic change had another consequence: Charles IV had also been King of Navarre

This is a list of the kings and queens of Pamplona, later Navarre. Pamplona was the primary name of the kingdom until its union with Aragon (1076–1134). However, the territorial designation Navarre came into use as an alternative name in the ...

, but, unlike the crown of France, the crown of Navarre was not subject to Salic law. Philip VI was neither an heir nor a descendant of Joan I of Navarre

Joan I (14 January 1273 – 31 March/2 April 1305) ( eu, Joana) was Queen of Navarre and Countess of Champagne from 1274 until 1305; she was also Queen of France by marriage to King Philip IV. She founded the College of Navarre in Paris in 130 ...

, whose inheritance (the kingdom of Navarre, as well as the counties of Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

, Troyes, Meaux

Meaux () is a Communes of France, commune on the river Marne (river), Marne in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region in the Functional area (France), metropolitan area of Paris, Franc ...

, and Brie

Brie (; ) is a soft cow's-milk cheese named after Brie, the French region from which it originated (roughly corresponding to the modern ''département'' of Seine-et-Marne). It is pale in color with a slight grayish tinge under a rind of white mo ...

) had been in personal union with the crown of France for almost fifty years and had long been administered by the same royal machinery established by King Philip IV, the father of French bureaucracy. These counties were closely entrenched in the economic and administrative entity of the crown lands of France

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or (in French) ''domaine royal'' (from demesne) of France were the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France. While the term eventually came to refer to a territorial unit, the ...

, being located adjacent to Île-de-France. Philip, however, was not entitled to that inheritance; the rightful heiress was the surviving daughter of his cousin King Louis X, the future Joan II of Navarre, the heir general

In English law, heirs of the body is the principle that certain types of property pass to a descendant of the original holder, recipient or grantee according to a fixed order of kinship. Upon the death of the grantee, a designated inheritance such ...

of Joan I of Navarre. Navarre thus passed to Joan II, with whom Philip struck a deal regarding the counties in Champagne: she received vast lands in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

(adjacent to the fief in Évreux that her husband Philip III of Navarre

Philip III ( eu, Filipe, es, Felipe, french: Philippe; 27 March 1306 – 16 September 1343), called the Noble or the Wise, was King of Navarre from 1328 until his death. He was born a minor member of the French royal family but gained prominen ...

owned) as compensation, and he kept Champagne as part of the French crown lands.

Reign

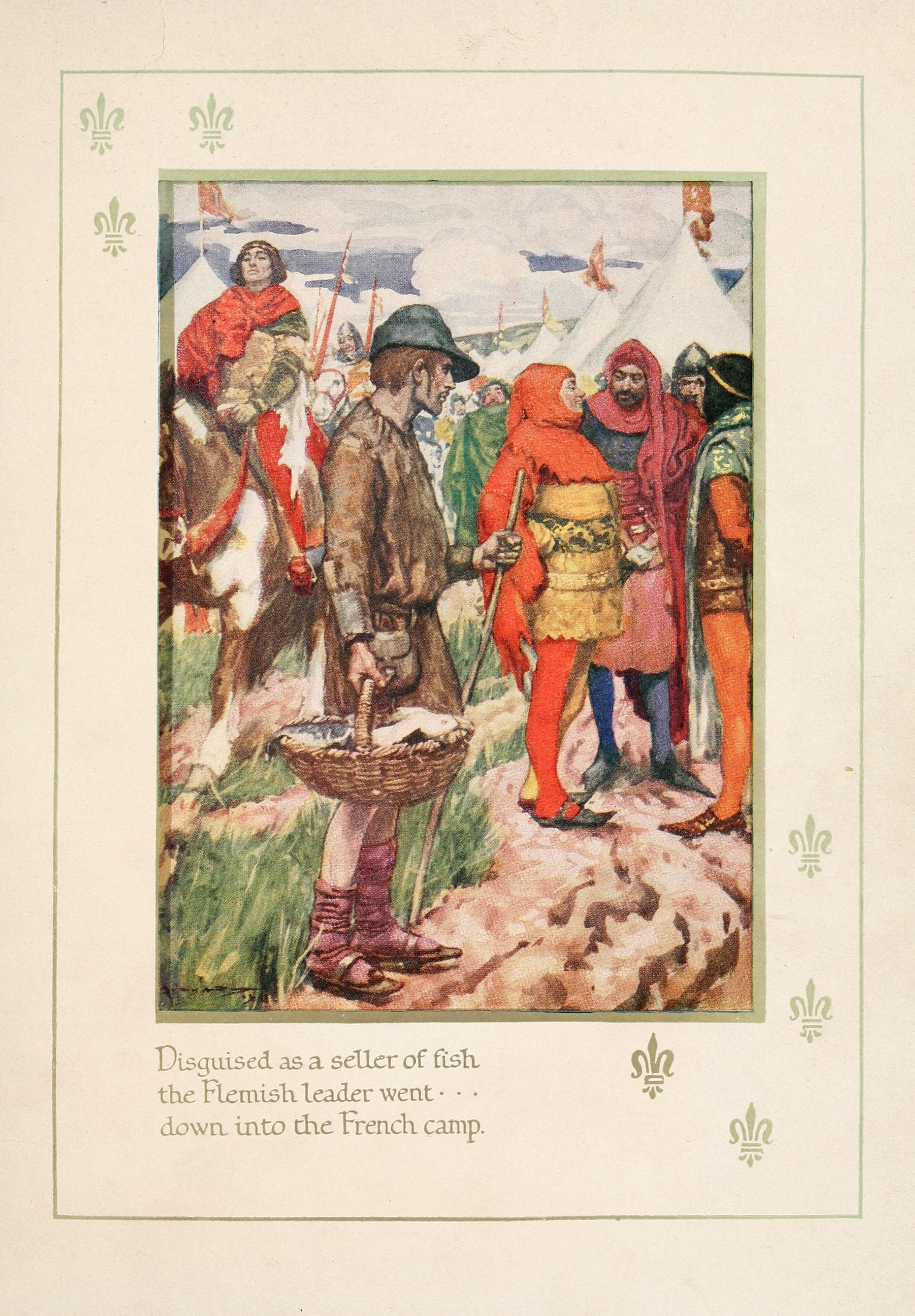

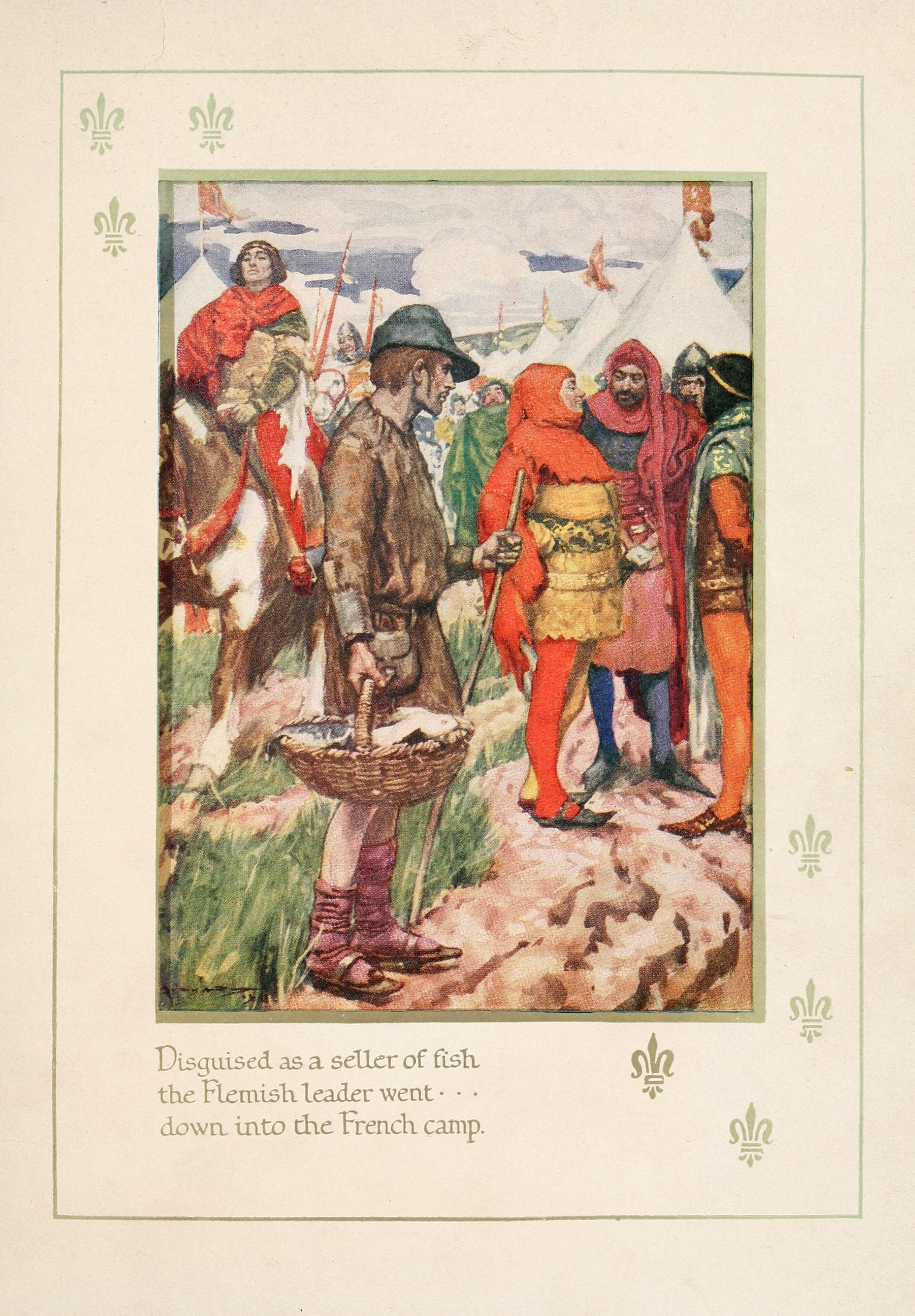

Philip's reign was plagued with crises, although it began with a military success inFlanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

at the Battle of Cassel (August 1328), where Philip's forces re-seated Louis I, Count of Flanders

Louis I ( – 26 August 1346, ruled 1322–1346) was Count of Flanders, Nevers and Rethel.

Life

He was the son of Louis I, Count of Nevers, and Joan, Countess of Rethel, and grandson of Robert III of Flanders. He succeeded his father as c ...

, who had been unseated by a popular revolution.Kelly DeVries, ''Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century'', (The Boydell Press, 1996), 102. Philip's wife, the able Joan the Lame, gave the first of many demonstrations of her competence as regent in his absence.

Philip initially enjoyed relatively amicable relations with Edward III, and they planned a crusade together in 1332, which was never executed. However, the status of the Duchy of Aquitaine remained a sore point, and tension increased. Philip provided refuge for David II of Scotland

David II (5 March 1324 – 22 February 1371) was King of Scots from 1329 until his death in 1371. Upon the death of his father, Robert the Bruce, David succeeded to the throne at the age of five, and was crowned at Scone in November 1331, beco ...

in 1334 and declared himself champion of his interests, which enraged Edward. By 1336, they were enemies, although not yet openly at war.

Philip successfully prevented an arrangement between the Avignon papacy

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon – at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire; now part of France – rather than in Rome. The situation a ...

and Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV, although in July 1337 Louis concluded an alliance with Edward III. The final breach with England came when Edward offered refuge to Robert III of Artois

Robert III of Artois (1287 – between 6 October & 20 November 1342) was Lord of Conches-en-Ouche, of Domfront, and of Mehun-sur-Yèvre, and in 1309 he received as appanage the county of Beaumont-le-Roger in restitution for the County of Arto ...

, formerly one of Philip's trusted advisers,Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 171-172. after Robert committed forgery to try to obtain an inheritance. As relations between Philip and Edward worsened, Robert's standing in England strengthened. On 26 December 1336, Philip officially demanded the extradition of Robert to France. On 24 May 1337, Philip declared that Edward had forfeited Aquitaine for disobedience and for sheltering the "king's mortal enemy", Robert of Artois. Thus began the Hundred Years' War, complicated by Edward's renewed claim to the throne of France in retaliation for the forfeiture of Aquitaine.

Hundred Years' War

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

was richer and more populous than England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and was at the height of its medieval glory. The opening stages of the war, accordingly, were largely successful for the French.

At sea, French privateers raided and burned towns and shipping all along the southern and southeastern coasts of England. The English made some retaliatory raids, including the burning of a fleet in the harbour of Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

,Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 320-328. but the French largely had the upper hand. With his sea power established, Philip gave orders in 1339 to begin assembling a fleet off the Zeeland

, nl, Ik worstel en kom boven("I struggle and emerge")

, anthem = "Zeeuws volkslied"("Zeelandic Anthem")

, image_map = Zeeland in the Netherlands.svg

, map_alt =

, m ...

coast at Sluys. In June 1340, however, in the bitterly fought Battle of Sluys

The Battle of Sluys (; ), also called the Battle of l'Écluse, was a naval battle fought on 24 June 1340 between England and France. It took place in the roadstead of the port of Sluys (French ''Écluse''), on a since silted-up inlet between ...

, the English attacked the port and captured or destroyed the ships there, ending the threat of an invasion.

On land, Edward III largely concentrated upon Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

and the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, where he had gained allies through diplomacy and bribery. A raid in 1339 (the first '' chevauchée'') into Picardy ended ignominiously when Philip wisely refused to give battle. Edward's slender finances would not permit him to play a waiting game, and he was forced to withdraw into Flanders and return to England to raise more money. In July 1340, Edward returned and mounted the siege of Tournai. By September 1340, Edward was in financial distress, hardly able to pay or feed his troops, and was open to dialogue.Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 354-359. After being at Bouvines for a week, Philip was finally persuaded to send Joan of Valois, Countess of Hainaut

Joan of Valois (c. 1294 – 7 March 1352) was a Countess consort of Hainaut, Holland, and Zeeland, by marriage to William I, Count of Hainaut. She acted as regent of Hainaut and Holland several times during the absence of her spouse, and she als ...

, to discuss terms to end the siege. On 23 September 1340, a nine-month truce was reached.

So far, the war had gone quite well for Philip and the French. While often stereotyped as chivalry-besotten incompetents, Philip and his men had in fact carried out a successful Fabian strategy

The Fabian strategy is a military strategy where pitched battles and frontal assaults are avoided in favor of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection. While avoiding decisive battles, the side employing this strategy ...

against the debt-plagued Edward and resisted the chivalric blandishments of single combat or a combat of two hundred knights that he offered. In 1341, the War of the Breton Succession

The War of the Breton Succession (, ) was a conflict between the Counts of Blois and the Montforts of Brittany for control of the Sovereign Duchy of Brittany, then a fief of the Kingdom of France. It was fought between 1341 and 12 April 1 ...

allowed the English to place permanent garrisons in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. However, Philip was still in a commanding position: during negotiations arbitrated by the pope in 1343, he refused Edward's offer to end the war in exchange for the Duchy of Aquitaine in full sovereignty.

The next attack came in 1345, when the Earl of Derby

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the en ...

overran the Agenais (lost twenty years before in the War of Saint-Sardos

The War of Saint-Sardos was a short war fought between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France in 1324. The French invaded the English Duchy of Aquitaine. The war was a clear defeat for the English, and led indirectly to the overthrow of ...

) and took Angoulême, while the forces in Brittany under Sir Thomas Dagworth

Sir Thomas Dagworth (1276 – 20 July 1350) was an English knight and soldier, who led the joint English-Breton armies in Brittany during the Hundred Years' War.

Hundred Years War Breton War of Succession

In 1346 he led a small English force in ...

also made gains. The French responded in the spring of 1346 with a massive counter-attack against Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

, where an army under John, Duke of Normandy, besieged Derby at Aiguillon. On the advice of Godfrey Harcourt (like Robert III of Artois

Robert III of Artois (1287 – between 6 October & 20 November 1342) was Lord of Conches-en-Ouche, of Domfront, and of Mehun-sur-Yèvre, and in 1309 he received as appanage the county of Beaumont-le-Roger in restitution for the County of Arto ...

, a banished French nobleman), Edward sailed for Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

instead of Aquitaine. As Harcourt predicted, the Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

were ill-prepared for war, and many of the fighting men were at Aiguillon. Edward sacked and burned the country as he went, taking Caen and advancing as far as Poissy and then retreating before the army Philip had hastily assembled at Paris. Slipping across the Somme, Edward drew up to give battle at Crécy.

Close behind him, Philip had planned to halt for the night and reconnoitre the English position before giving battle the next day. However, his troops were disorderly, and the roads were jammed by the rear of the army coming up, and by the local peasantry furiously calling for vengeance on the English. Finding them hopeless to control, he ordered a general attack as evening fell. Thus began the Battle of Crécy. When it was done, the French army had been annihilated and a wounded Philip barely escaped capture. Fortune had turned against the French.

The English seized and held the advantage. Normandy called off the siege of Aiguillon and retreated northward, while Sir Thomas Dagworth

Sir Thomas Dagworth (1276 – 20 July 1350) was an English knight and soldier, who led the joint English-Breton armies in Brittany during the Hundred Years' War.

Hundred Years War Breton War of Succession

In 1346 he led a small English force in ...

captured Charles of Blois

Charles of Blois-Châtillon (131929 September 1364), nicknamed "the Saint", was the legalist Duke of Brittany from 1341 until his death, via his marriage to Joan, Duchess of Brittany and Countess of Penthièvre, holding the title against the c ...

in Brittany. The English army pulled back from Crécy to mount the siege of Calais; the town held out stubbornly, but the English were determined, and they easily supplied across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. Philip led out a relieving army in July 1347, but unlike the Siege of Tournai, it was now Edward who had the upper hand. With the plunder of his Norman expedition and the reforms he had executed in his tax system, he could hold to his siege lines and await an attack that Philip dared not deliver. It was Philip who marched away in August, and the city capitulated shortly thereafter.

Final years

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the Black Death struck France and in the next few years killed one-third of the population, including Queen Joan. The resulting labour shortage caused inflation to soar, and the king attempted to fix prices, further destabilising the country. His second marriage to his son's betrothed Blanche of Navarre alienated his son and many nobles from the king.

Philip's last major achievement was the acquisition of the

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the Black Death struck France and in the next few years killed one-third of the population, including Queen Joan. The resulting labour shortage caused inflation to soar, and the king attempted to fix prices, further destabilising the country. His second marriage to his son's betrothed Blanche of Navarre alienated his son and many nobles from the king.

Philip's last major achievement was the acquisition of the Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

and the territory of Montpellier in the Languedoc in 1349. At his death in 1350, France was very much a divided country filled with social unrest. Philip VI died at Coulombes Abbey, Eure-et-Loir, on 22 August 1350 and is interred with his first wife, Joan of Burgundy, in Saint Denis Basilica

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

, though his viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a f ...

were buried separately at the now demolished church of Couvent des Jacobins in Paris. He was succeeded by his first son by Joan of Burgundy, who became John II.

Marriages and children

Philip married twice. In July 1313, he married Joan the Lame (french: link=no, Jeanne), daughter ofRobert II, Duke of Burgundy

Robert II of Burgundy (1248 – 21 March 1306) was Duke of Burgundy between 1272 and 1306 as well as titular King of Thessalonica. Robert was the third son of duke Hugh IV and Yolande of Dreux.

He married Agnes, youngest daughter of Louis IX o ...

, and Agnes of France, the youngest daughter of King Louis IX of France. She was thus Philip's first cousin once removed. The couple had the following children:

# King John II of France (26 April 1319 – 8 April 1364)Marguerite Keane, ''Material Culture and Queenship in 14th-century France'', (Brill, 2016), 17.

# Marie of France (1326 – 22 September 1333), who died aged only seven, but was already married to John of Brabant, the son and heir of John III, Duke of Brabant; no issue.

# Louis (born and died 17 January 1329).

# Louis (8 June 1330 – 23 June 1330)

# A son ohn?(born and died 2 October 1333).

# A son (28 May 1335), stillborn

# Philip of Orléans (1 July 1336 – 1 September 1375), Duke of Orléans

# Joan (born and died November 1337)

# A son (born and died summer 1343)

After Joan died in 1349, Philip married Blanche of Navarre,''Identity Politics and Rulership in France: Female Political Place and the Fraudulent Salic Law in Christine de Pizan and Jean de Montreuil'', Sarah Hanley, ''Changing Identities in Early Modern France'', ed. Michael Wolfe, (Duke University Press, 1996), 93 n45. daughter of Queen Joan II of Navarre

Joan II (french: Jeanne; 28 January 1312 – 6 October 1349) was Queen of Navarre from 1328 until her death. She was the only surviving child of Louis X of France, King of France and Navarre, and Margaret of Burgundy. Joan's paternity was dubiou ...

and Philip III of Navarre

Philip III ( eu, Filipe, es, Felipe, french: Philippe; 27 March 1306 – 16 September 1343), called the Noble or the Wise, was King of Navarre from 1328 until his death. He was born a minor member of the French royal family but gained prominen ...

, on 11 January 1350. They had one daughter:

* Joan (Blanche) of France (May 1351 – 16 September 1371), who was intended to marry John I of Aragon

John I (27 December 1350 – 19 May 1396), called by posterity the Hunter or the Lover of Elegance, but the Abandoned in his lifetime, was the King of Aragon from 1387 until his death.

Biography

John was the eldest son of Peter IV and his third ...

, but who died during the journey.

In fiction

Philip is a character in ''Les Rois maudits'' ('' The Accursed Kings''), a series of French historical novels byMaurice Druon

Maurice Druon (23 April 1918 – 14 April 2009) was a French novelist and a member of the Académie Française, of which he served as "Perpetual Secretary" (chairman) between 1985 and 1999.

Life and career

Born in Paris, France, Druon was the s ...

. He was portrayed by Benoît Brione in the 1972 French miniseries adaptation of the series, and by Malik Zidi in the 2005 adaptation.

References

Sources

* , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip 06 Of France 1293 births 1350 deaths 13th-century French people 14th-century kings of France 14th-century French people 14th-century peers of France Captains General of the Church Counts of Anjou Counts of Valois Heirs presumptive to the French throne House of Valois People from Eure-et-Loir People of the Hundred Years' War Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis