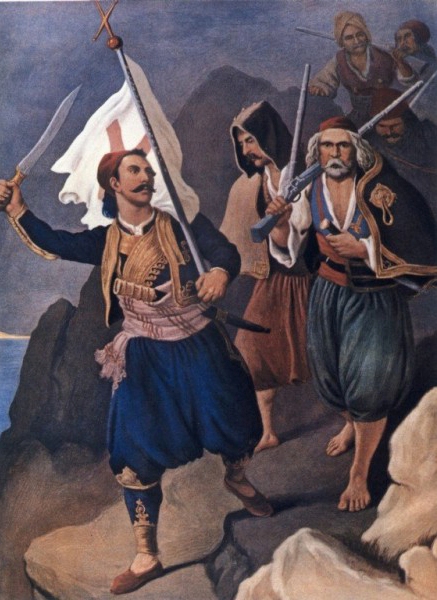

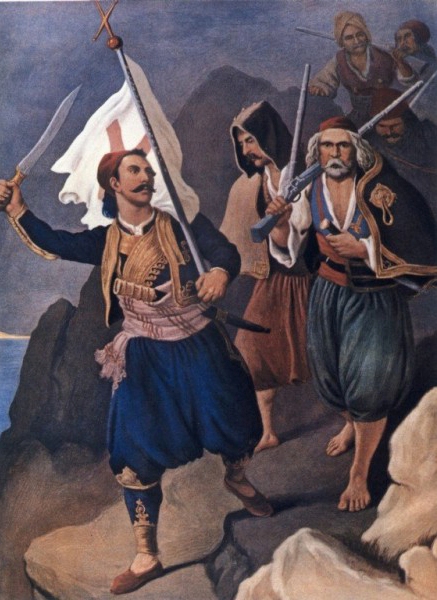

Petros Mavromichalis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Petros Mavromichalis (; 1765–1848), also known as Petrobey ( ), was a

Petros was born on 6 August 1765, the son of leader Pierros "Mavromichalis" Pierrakos and Katerina Koutsogrigorakos, a doctor's daughter.

Mavromichalis' family had a long history of uprising against the

Petros was born on 6 August 1765, the son of leader Pierros "Mavromichalis" Pierrakos and Katerina Koutsogrigorakos, a doctor's daughter.

Mavromichalis' family had a long history of uprising against the  By 1814, the reorganized Maniots again became a threat to the Ottomans, and the Sultan offered a number of concessions to Pierrakos, including his being named Bey, or ''Chieftain'', of Mani - in effect formalizing the de facto status of autonomy the region had maintained for years. Under the leadership of Petrobey, as he was now called, the Maniot state and the Pierrakos family in particular were powerful enough to control the areas of the southern Peloponnese against Albanian raiders on behalf of the Sultan. Still, Petrobey was an active participant in the various designs of the Moreot (, 'captains, commanders of warbands') for an uprising. In 1818, he became a member of the ''

By 1814, the reorganized Maniots again became a threat to the Ottomans, and the Sultan offered a number of concessions to Pierrakos, including his being named Bey, or ''Chieftain'', of Mani - in effect formalizing the de facto status of autonomy the region had maintained for years. Under the leadership of Petrobey, as he was now called, the Maniot state and the Pierrakos family in particular were powerful enough to control the areas of the southern Peloponnese against Albanian raiders on behalf of the Sultan. Still, Petrobey was an active participant in the various designs of the Moreot (, 'captains, commanders of warbands') for an uprising. In 1818, he became a member of the '' After the summer of 1822, Petrobey retired from battle, leaving the leadership of his troops to his sons (two of whom were killed fighting). He continued to act as a mediator whenever disputes arose among the ', and acted as the leader of the

After the summer of 1822, Petrobey retired from battle, leaving the leadership of his troops to his sons (two of whom were killed fighting). He continued to act as a mediator whenever disputes arose among the ', and acted as the leader of the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

general, politician and the leader of the Maniot

The Maniots or Maniates ( el, Μανιάτες) are the inhabitants of Mani Peninsula, located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes and the peninsula as ''Maina''. ...

people during the first half of the 19th century. His family had a long history of revolts against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, which ruled most of what is now Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. His grandfather Georgios and his father Pierros were among the leaders of the Orlov Revolt.

Life

Petros was born on 6 August 1765, the son of leader Pierros "Mavromichalis" Pierrakos and Katerina Koutsogrigorakos, a doctor's daughter.

Mavromichalis' family had a long history of uprising against the

Petros was born on 6 August 1765, the son of leader Pierros "Mavromichalis" Pierrakos and Katerina Koutsogrigorakos, a doctor's daughter.

Mavromichalis' family had a long history of uprising against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, which ruled most of what is now Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. His grandfather Georgakis Mavromichalis and his father Pierros "Mavromichalis" Pierrakos were among the leaders of the Orlov Revolt. The revolt was followed by a period of infighting between the leaders of Mani

Mani may refer to:

Geography

* Maní, Casanare, a town and municipality in Casanare Department, Colombia

* Mani, Chad, a town and sub-prefecture in Chad

* Mani, Evros, a village in northeastern Greece

* Mani, Karnataka, a village in Dakshina ...

; soon, young Petros gained a strong reputation for mediating the disputes and reuniting the warring families. Due to the failure of several uprisings against the Turks, he was successful in helping many klephts

Klephts (; Greek κλέφτης, ''kléftis'', pl. κλέφτες, ''kléftes'', which means "thieves" and perhaps originally meant just "brigand": "Other Greeks, taking to the mountains, became unofficial, self-appointed armatoles and were kno ...

and other rebels to escape to the French-controlled Heptanese, which gave him a useful contact with a potential ally. During that period he possibly made an alliance with Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, who was fighting in Egypt; Napoleon was to strike the Ottoman Empire in coordination with a Greek revolt. Napoleon's failure in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

doomed that plan.

By 1814, the reorganized Maniots again became a threat to the Ottomans, and the Sultan offered a number of concessions to Pierrakos, including his being named Bey, or ''Chieftain'', of Mani - in effect formalizing the de facto status of autonomy the region had maintained for years. Under the leadership of Petrobey, as he was now called, the Maniot state and the Pierrakos family in particular were powerful enough to control the areas of the southern Peloponnese against Albanian raiders on behalf of the Sultan. Still, Petrobey was an active participant in the various designs of the Moreot (, 'captains, commanders of warbands') for an uprising. In 1818, he became a member of the ''

By 1814, the reorganized Maniots again became a threat to the Ottomans, and the Sultan offered a number of concessions to Pierrakos, including his being named Bey, or ''Chieftain'', of Mani - in effect formalizing the de facto status of autonomy the region had maintained for years. Under the leadership of Petrobey, as he was now called, the Maniot state and the Pierrakos family in particular were powerful enough to control the areas of the southern Peloponnese against Albanian raiders on behalf of the Sultan. Still, Petrobey was an active participant in the various designs of the Moreot (, 'captains, commanders of warbands') for an uprising. In 1818, he became a member of the ''Filiki Eteria

Filiki Eteria or Society of Friends ( el, Φιλικὴ Ἑταιρεία ''or'' ) was a secret organization founded in 1814 in Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow the Ottoman rule of Greece and establish an independent Greek state. (''ret ...

'', and in 1819 he brokered a formal pact among the major ' families. On 17 March 1821 Petrobey raised his war flag in Areopoli

Areopoli ( el, Αρεόπολη; before 1912 , ) is a town on the Mani Peninsula, Laconia, Greece.

The word ''Areopoli'', which means "city of Ares", the ancient Greek god of war, became the official name in 1912. It was the seat of Oitylo ...

s, effectively signaling the start of the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

. His troops marched into Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regi ...

and took the city on 23 March.

After the summer of 1822, Petrobey retired from battle, leaving the leadership of his troops to his sons (two of whom were killed fighting). He continued to act as a mediator whenever disputes arose among the ', and acted as the leader of the

After the summer of 1822, Petrobey retired from battle, leaving the leadership of his troops to his sons (two of whom were killed fighting). He continued to act as a mediator whenever disputes arose among the ', and acted as the leader of the Messenian Senate

The Messenian Senate ( el, Μεσσηνιακή Σύγκλητος) was the first government of the Greek Revolution. It was the first move towards the creation of the Peloponnesian Senate.

History

The Messenian Senate was formed at Kalamata o ...

, a council of prominent revolutionary leaders. He also tried to seek support from the West by sending a number of letters to leaders and philhellenes

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as Lord Byron and Charles Nicolas Fabvier to advocate for Greek ...

in Europe and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

After the revolution, Petrobey became a member of the first Greek Senate

The Greek Senate ( el, Γερουσία, '' Gerousia'') was the upper chamber of the parliament in Greece, extant several times in the country's history.

Local senates during the War of Independence

During the early stages of the Greek War of ...

, under the leadership of Ioannis Kapodistrias

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (10 or 11 February 1776 – 9 October 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias ( el, Κόμης Ιωάννης Αντώνιος Καποδίστριας, Komis Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias; russian: � ...

. The two men soon clashed as a result of Kapodistrias' insistence on establishing a centralized regional administration based on political appointees, replacing the traditional system of family loyalties. Petros' brother Ioannis led a revolt against the appointed governor of Lakonia; the two brothers were invited to meet Kapodistrias and negotiate a solution but when they showed up, they were arrested. From his prison cell, Petros tried to negotiate a settlement with Kapodistrias; the latter refused. The crisis was then settled by more traditional means: Petros' brother Konstantinos and his son Georgios Georgios (, , ) is a Greek name derived from the word ''georgos'' (, , "farmer" lit. "earth-worker"). The word ''georgos'' (, ) is a compound of ''ge'' (, , "earth", "soil") and ''ergon'' (, , "task", "undertaking", "work").

It is one of the mo ...

assassinated Kapodistrias on 9 October 1831. Petros publicly disapproved of the murder. Kapodistrias was succeeded by King Otto, whose attitude towards the ''kapetanaioi'' was much friendlier. Petros became vice-president of the Council of State, and later a senator. He was also one of the few Greeks to be awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

The Order of the Redeemer ( el, Τάγμα του Σωτήρος, translit=Tágma tou Sotíros), also known as the Order of the Saviour, is an order of merit of Greece. The Order of the Redeemer is the oldest and highest decoration awarded by the ...

.

He died in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

on 17 January 1848 and was buried with the highest honors.

References

Sources

* Κ. Ζησίου, Οι Μαυρομιχάλαι. Συλλογή των περί αυτών γραφέντων, (K. Zisiou, The Mavromichalai. Collection of their own scripts, Athens,1903) * Ανάργυρου Κουτσιλιέρη, Ιστορία της Μάνης, (Anargiros Koutsilieris, History of Mani, Athens, 1996) *Αγαπητός Σ. Αγαπητός (1877). Οι Ένδοξοι Έλληνες του 1821, ή Οι Πρωταγωνισταί της Ελλάδος σελ. 40-47. Τυπογραφείον Α. Σ. Αγαπητού, Εν Πάτραις -ανακτήθηκε 13 Αυγούστου 2009-. (Agapitos S. Agapitos, The 1821 Glorious Greeks, The Protagonists of Greece, pg 40-47. A.S. Agapitou Press, Patras -1877 - reimpression 8.13.2009) {{DEFAULTSORT:Mavromichalis, Petros 1765 births 1848 deaths 19th-century heads of state of Greece 19th-century prime ministers of Greece Ottoman-era Greek primates People from East Mani Members of the Filiki Eteria Petros Greek people of the Greek War of Independence Prime Ministers of Greece Speakers of the Hellenic Parliament Members of the Greek Senate