Petr Stolypin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

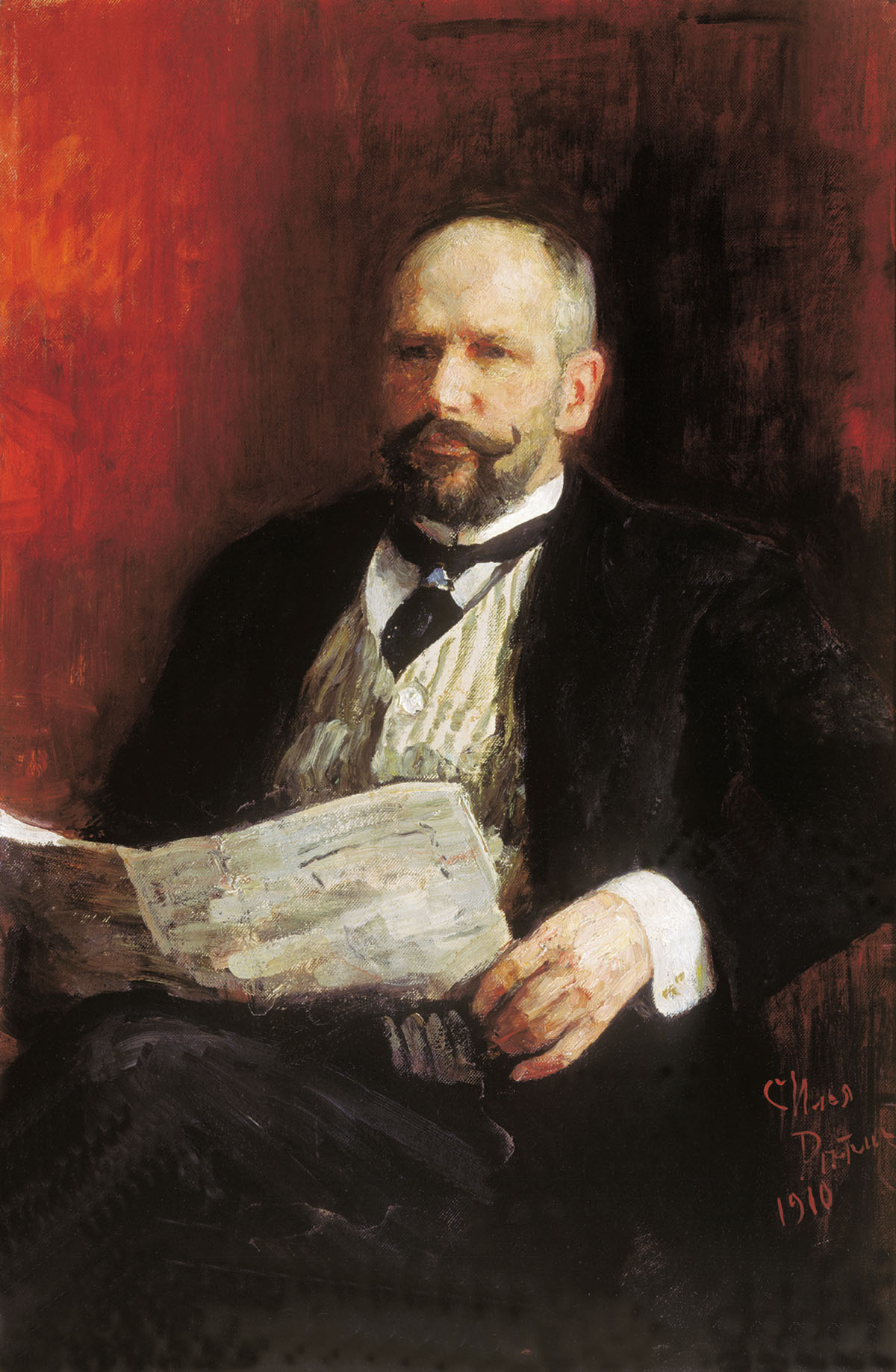

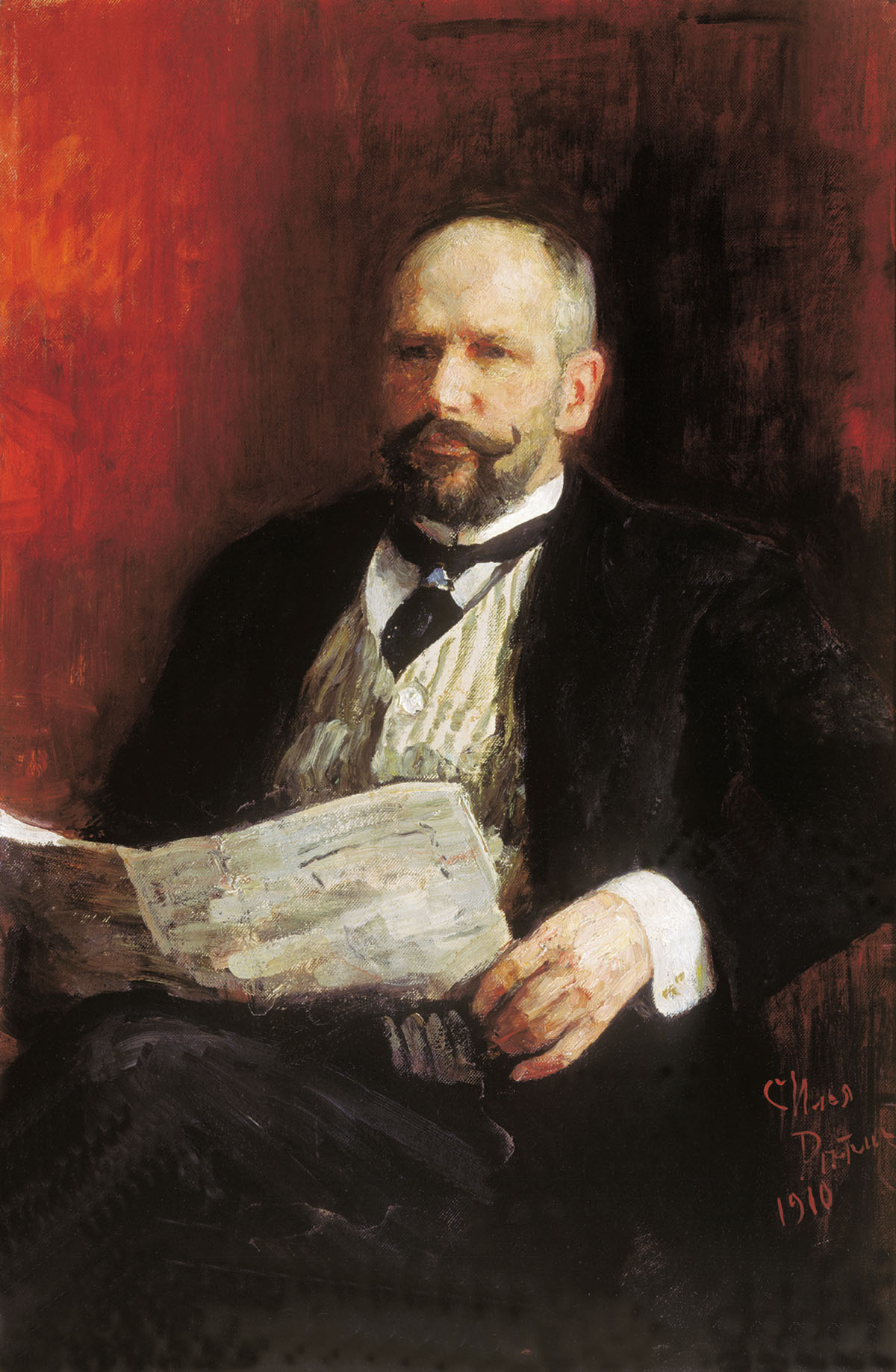

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third

In 1881 Stolypin studied agriculture at

In 1881 Stolypin studied agriculture at

From 1869, Stolypin spent his childhood years in Kalnaberžė manor (now

From 1869, Stolypin spent his childhood years in Kalnaberžė manor (now

In February 1903 he became governor of Saratov. Stolypin is known for suppressing strikers and peasant unrest in January 1905. According to

In February 1903 he became governor of Saratov. Stolypin is known for suppressing strikers and peasant unrest in January 1905. According to

On 25 August 1906, three assassins from the Union of Socialists Revolutionaries Maximalists, wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his

On 25 August 1906, three assassins from the Union of Socialists Revolutionaries Maximalists, wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his  In Saratov, Stolypin had come to the conviction that the

In Saratov, Stolypin had come to the conviction that the

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings that an assassination plot was afoot as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , there was a performance of

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings that an assassination plot was afoot as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , there was a performance of

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by revolutionary unrest and discontent was widespread among the population. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by revolutionary unrest and discontent was widespread among the population. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

online

* Pares, Bernard. ''A History of Russia'' (1926) pp 495–506

Online

* Pares, Bernard. '' The Fall of the Russian Monarchy'' (1939) pp 94–143

Online

*

Stolypin and the Russian Agrarian Miracle

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stolypin, Petr 1862 births 1911 deaths 1911 murders in Europe 20th-century murders in Russia Marshals of nobility Heads of government of the Russian Empire Interior ministers of Russia Assassinated politicians of the Russian Empire Deaths by firearm in Russia People murdered in Russia Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Assassinated heads of government Burials at the Refectory Church, Kyiv Pechersk Lavra People from Dresden Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Male murder victims Russian duellists Russian untitled nobility Russian monarchists

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

and the interior minister of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

from 1906 until his assassination in 1911. The greatest reformer of Russian society and economy; his reforms caused unprecedented growth of Russian state which was stopped by his assassination only.

Born in Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, Germany, to a prominent Russian aristocratic family, Stolypin became involved in government from his early 20s. His successes in public service led to rapid promotions, culminating in his appointment as interior minister under prime minister Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин, Iván Lógginovich Goremýkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 a ...

in April 1906. In July, Goremykin resigned and was succeeded as prime minister by Stolypin.

As prime minister, Stolypin initiated major agrarian reform Agrarian reform can refer either, narrowly, to government-initiated or government-backed redistribution of agricultural land (see land reform) or, broadly, to an overall redirection of the agrarian system of the country, which often includes land ...

s, known as the Stolypin reform

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted during the tenure of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Most, if not all, of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known ...

, that granted the right of private land ownership to the peasantry. His tenure was also marked by increased revolutionary unrest, to which he responded with a new system of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

that allowed for the arrest, speedy trial, and execution of accused offenders. Subject to numerous assassination attempts, Stolypin was fatally shot in September 1911 by revolutionary Dmitry Bogrov

Dmitry Grigoriyevich Bogrov ( – ) () was the assassin of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.

On Bogrow was sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on in the Kiev fortress Lyssa Hora.

Stolypin's widow had campaigned in vain to spare the ass ...

in Kiev.

Stolypin was a monarchist and hoped to strengthen the throne by modernizing the rural Russian economy. Modernity and efficiency, rather than democracy, were his goals. He argued that the land question could only be resolved and revolution averted when the peasant commune

Obshchina ( rus, община, p=ɐpˈɕːinə, literally "commune") or mir (russian: мир, literally "society", among other meanings), or selskoye obshchestvo (russian: сельское общество, literally "rural community", official ...

was abolished and a stable landowning class of peasants, the kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

s, would have a stake in the ''status quo''. His successes and failures have been the subject of heated controversies among scholars, who agree he was one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with clearly defined public policies and the determination to undertake major reforms.

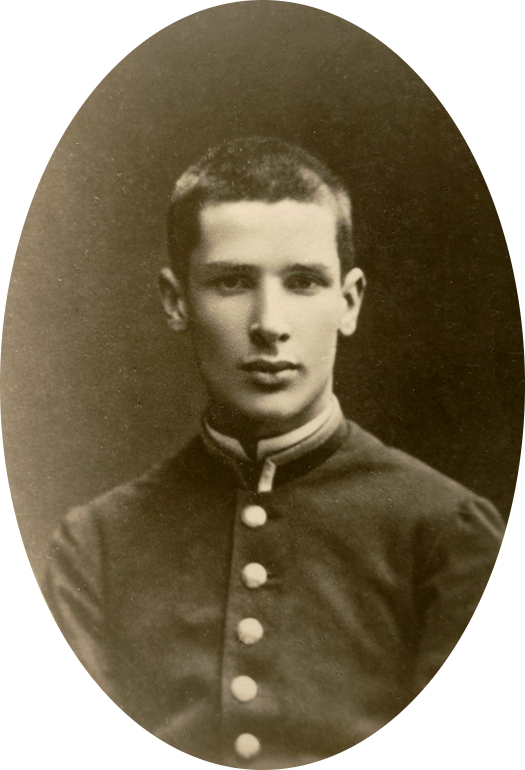

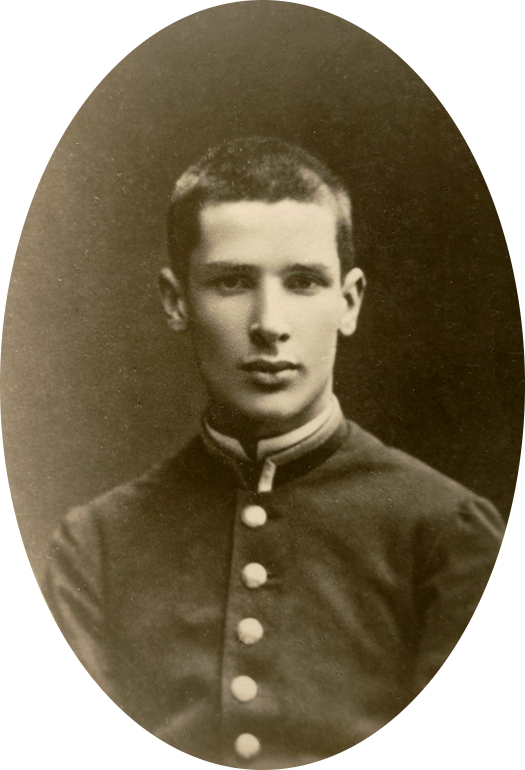

Early life and career

Stolypin was born atDresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

in the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Saxo ...

, on 14 April 1862, and was baptized on 24 May in the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

in that city. His father, Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821–99), was at the time a Russian envoy.

Stolypin's family was prominent in the Russian aristocracy

The Russian nobility (russian: дворянство ''dvoryanstvo'') originated in the 14th century. In 1914 it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members (about 1.1% of the population) in the Russian Empire.

Up until the February Revolution ...

, his forebears having served the tsars since the 16th century, and as a reward for their service had accumulated huge estates in several provinces. His father Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821–99), was a general in the Russian artillery, the governor of Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia ( bg, Източна Румелия, Iztochna Rumeliya; ota, , Rumeli-i Şarkî; el, Ανατολική Ρωμυλία, Anatoliki Romylia) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, '' vilayet'' in Turkish) in the Ott ...

and commandant of the Kremlin Palace

The Grand Kremlin Palace (russian: Большой Кремлёвский дворец - ) was built from 1837 to 1849 in Moscow, Russia, on the site of the estate of the Grand Princes, which had been established in the 14th century on Borovits ...

guard. He was married twice. His second wife, Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (''née'' Gorchakov

Gorchakov, or Gortchakoff (russian: Горчако́в), is a Russian princely family of Rurikid stock that is descended from the Rurikid sovereigns of Peremyshl, Russia.

Aleksey Gorchakov

The family first achieved prominence during the reign of ...

a; 1827–89), was the daughter of Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov

Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov (russian: Михаи́л Дми́триевич Горчако́в, pl, Michaił Dymitrowicz Gorczakow; – , Warsaw) was a Russian General of the Artillery from the Gorchakov family, who commanded the R ...

, the Commanding general of the Russian infantry during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and later the governor general of Warsaw.

Pyotr grew up on the family estate ''Serednikovo'' (russian: Середниково) in Solnechnogorsky District

Solnechnogorsky District (russian: Солнечного́рский райо́н) is an administrativeLaw #11/2013-OZ and municipalLaw #27/2005-OZ district (raion), one of the thirty-six in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It is located in the northwest o ...

, once inhabited by Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (; russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjurʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲɛrməntəf; – ) was a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucas ...

, near Moscow Governorate. In 1879 the family moved to Oryol. Stolypin and his brother Aleksandr studied at the Oryol Boys College where he was described by his teacher, B. Fedorova, as 'standing out among his peers for his rationalism and character.'

In 1881 Stolypin studied agriculture at

In 1881 Stolypin studied agriculture at St. Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter t ...

where one of his teachers was Dmitri Mendeleev. He entered government service upon graduating in 1885, writing his thesis on tobacco growing in the south of Russia. It is unclear if he joined the Ministry of State Property

The Ministry of State Property, sometimes translated as the Ministry of State Domains, (russian: Министерство государственных имуществ (МГИ), ''Ministerstvo gosudarstvennykh imushestv (MGI)'') was the minis ...

or Internal Affairs.

In 1884, Stolypin married Olga Borisovna von Neidhart Neidhart is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Christian Neidhart, German football manager

*Jim Neidhart, Canadian professional wrestler

*Natalya Neidhart

Natalie Katherine Neidhart-Wilson (born May 27, 1 ...

whose family was of a similar standing to Stolypin's. They married whilst Stolypin was still a student, an uncommon occurrence at the time. The marriage began in tragic circumstances: Olga had been engaged to Stolypin's brother, Mikhail, who died in a duel. The marriage was a happy one, devoid of scandal. The couple had five daughters and one son.

Lithuania

Stolypin spent much of his life and career in Lithuania, then administratively known as Northwestern Krai of the Russian Empire.Kėdainiai district

Kėdainiai () is one of the oldest cities in Lithuania. It is located north of Kaunas on the banks of the Nevėžis River. First mentioned in the 1372 Livonian Chronicle of Hermann de Wartberge, its population is 23,667. Its old town dates to ...

of Lithuania), built by his father, a place that remained his favorite residence for the rest of life. In 1876, the Stolypin family moved to Vilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

(now Vilnius), where he attended grammar school.

Stolypin served as marshal of the Kovno Governorate

Kovno Governorate ( rus, Ковенская губеpния, r=Kovenskaya guberniya; lt, Kauno gubernija) or Governorate of Kaunas was a governorate ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire. Its capital was Kaunas (Kovno in Russian). It was forme ...

(now Kaunas, Lithuania) between 1889 and 1902. This public service gave him an inside view of local needs and allowed him to develop administrative skills. His thinking was influenced by the single-family farmstead system of the Northwestern Krai

A krai or kray (; russian: край, , ''kraya'') is one of the types of federal subjects of modern Russia, and was a type of geographical administrative division in the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR.

Etymologically, the word is relat ...

, and he later sought to introduce the land reform based on private ownership throughout the Russian Empire.

Stolypin's service in Kovno was deemed a success by the Russian government. He was promoted seven times, culminating in his promotion to the rank of state councilor in 1901. Four of his daughters were also born during this period; his daughter Maria recalled: "this was the most calm period fhis life".

In May 1902 Stolypin was appointed governor in Grodno Governorate

The Grodno Governorate, (russian: Гро́дненская губе́рнiя, translit=Grodnenskaya guberniya, pl, Gubernia grodzieńska, be, Гродзенская губерня, translit=Hrodzenskaya gubernya, lt, Gardino gubernija, u ...

, where he was the youngest person ever appointed to this position.

Governor of Saratov

In February 1903 he became governor of Saratov. Stolypin is known for suppressing strikers and peasant unrest in January 1905. According to

In February 1903 he became governor of Saratov. Stolypin is known for suppressing strikers and peasant unrest in January 1905. According to Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes () is a British historian and writer. Until his retirement, he was Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Figes is known for his works on Russian history, such as '' A People's Tragedy'' (1996), ''Nata ...

, its peasants were among the poorest and most rebellious in the whole of the country.O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, p. 223. It seems he cooperated with the zemstvos, the local government. He gained a reputation as the only governor able to keep a firm hold on his province during the Revolution of 1905, a period of widespread revolt. The roots of unrest lay partly in the Emancipation Reform of 1861, which had given land to the Obshchina, instead of individually to the newly freed serfs. Stolypin was the first governor to use effective police methods. Some sources suggest that he had a police record on every adult male in his province.

Interior minister and prime minister

Stolypin's successes as provincial governor led to Stolypin being appointed interior minister underIvan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: Ива́н Лóггинович Горемы́кин, Iván Lógginovich Goremýkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 a ...

in April 1906. He instigated a new track of the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

along the Amur River within Russian borders.

After two months, Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov

Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov (transliterated at the time as Trepoff) (15 December 1850 – 15 September 1906) was Head of the Moscow police, Governor-General of St. Petersburg with extraordinary powers, and Assistant Interior Minister with full contr ...

suggested the absent-minded Goremykin ought to step down and secretly met with Pavel Milyukov, who promoted a cabinet with only Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

s, which in his opinion would soon enter into a violent conflict with Tsar Nicholas II and fail. Trepov opposed Stolypin, who promoted a coalition cabinet. Georgy Lvov and Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Гучко́в) (14 October 1862 – 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government. ...

tried to convince the tsar to accept liberals in the new government.

When Goremykin, described by his predecessor Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

as a bureaucratic nonentity, resigned on , Nicholas II appointed Stolypin to serve as Prime Minister, while continuing on as Minister of the Interior, an unusual concentration of power in Imperial Russia. He dissolved the Duma, despite the reluctance of some of its more radical members, in order to facilitate government cooperation. In response, 120 Kadet and 80 Trudovik and Social Democrat deputies went to Vyborg (then a part of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecess ...

and thus beyond the reach of Russian police) and responded with the Vyborg Manifesto

The Vyborg Manifesto (russian: Выборгское воззвание, translit=Vyborgskoye Vozzvaniye, fi, Viipurin manifesti, sv, Viborgsmanifestet); also called the Vyborg Appeal) was a proclamation signed by several Russian politicians, pri ...

(or the "Vyborg Appeal"), written by Pavel Milyukov. Stolypin allowed the signers to return to the capital unmolested.

On 25 August 1906, three assassins from the Union of Socialists Revolutionaries Maximalists, wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his

On 25 August 1906, three assassins from the Union of Socialists Revolutionaries Maximalists, wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an outbu ...

on Aptekarsky Island

Aptekarsky Island (russian: Апте́карский о́стров, , "Apothecary Island", fi, Korpisaari, "Deep Forest Island") is a relatively small island situated in the northern part of the Neva delta. It is separated from Petrogradsky Is ...

. Stolypin was only slightly injured by flying splinters, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter lost both legs and later succumbed to her injuries at the hospital, his 3-year-old son broke a leg, standing with his sister on the balcony. Stolypin moved into the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

. In October 1906, at the request of the Tsar, Grigori Rasputin paid a visit to the wounded child. On 9 November by an imperial decree far reaching changes in land tenure law were put in operation which attacked in one sweep the communal and the household (family) property system.

Stolypin changed the nature of the First Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four tim ...

to attempt to make it more willing to pass legislation proposed by the government. On 8 June 1907, Stolypin dissolved the Second Duma, and 15 Kadets, who had been in contact with terrorists, were arrested; he also changed the weight of votes in favor of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower-class votes. The leading Kadets were ineligible. This affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more conservative members, more willing to cooperate with the government. It changed Georgy Lvov from a moderate liberal into a radical.

In Saratov, Stolypin had come to the conviction that the

In Saratov, Stolypin had come to the conviction that the open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

had to be abolished; communal land tenure

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land owned by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individual ...

had to go. The chief obstacle appeared to be the Mir (commune)

Obshchina ( rus, община, p=ɐpˈɕːinə, literally "commune") or mir (russian: мир, literally "society", among other meanings), or selskoye obshchestvo (russian: сельское общество, literally "rural community", official ...

. Its dissolution and the individualization of peasant land ownership became the leading objectives of agrarian policy. Like in Denmark, he introduced land reforms in order to resolve peasant grievances and quell dissent. Stolypin proposed his own landlord-sided reform in opposition to those democratic proposals which led to the dissolution of the first two Russian parliaments. Stolypin's reforms aimed to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of market-oriented smallholding

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology ...

landowners, who would thus support societal order. (See article " Stolypin's Reform"). He was assisted by Alexander Krivoshein

Alexander Vasilyevich Krivoshein (russian: Александр Васильевич Кривошеин) (July 19 (31 ( N.S.), 1857, Warsaw – October 28, 1921, Berlin) was a Russian monarchist politician and Minister of Agriculture under Pyotr S ...

, who in 1908 became the Minister of Agriculture. In June 1908 Stolypin lived in a wing of the Yelagin Palace

Yelagin Palace (Елагин дворец; also ''Yelaginsky'' or ''Yelaginoostrovsky Dvorets'') is a Palladian villa on Yelagin Island in Saint Petersburg, which served as a royal summer palace during the reign of Alexander I. The villa was desi ...

; where the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

also convened.

Supported by the Peasants' Land Bank, the amount of credit cooperatives increased from 1908. Russian industry was booming. Stolypin tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and worked towards increasing the power of local governments, but the zemstvos adopted an attitude hostile to the government.

Stolypin attempted to improve the acrimonious relations between the Russian Orthodox and Jewish citizens at the level of nationalities policy. Sergey Sazonov was the brother-in-law of Stolypin and did his best to further his career; in 1910 he became Minister of Foreign Affairs, following Count Alexander Izvolsky

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Петро́вич Изво́льский, , Moscow – 16 August 1919, Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with Grea ...

. Around 1910 the press started a campaign against Rasputin, who was accused of paying too much attention to young girls and women. Stolypin wanted to ban him from the capital and threatened to prosecute him as a sectarian. Rasputin went on a trip to Jerusalem and came back to St. Petersburg only after Stolypin's death.

On 14 June 1910, Stolypin's land reform measures became a full-fledged law. He also proposed spreading the system of zemstvo

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexande ...

to the southwestern provinces of Asian Russia

North Asia or Northern Asia, also referred to as Siberia, is the northern region of Asia, which is defined in geographical terms and is coextensive with the Asian part of Russia, and consists of three Russian regions east of the Ural Mountains: ...

. It was originally slated to pass with a narrow majority, but Stolypin's political opponents stopped it. "Stolypin resigned in March of 1911 from the fractious and chaotic Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

after the failure of his land-reform bill". Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

decided to look for a successor to Stolypin and considered Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

, Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (russian: Влади́мир Никола́евич Коко́вцов; – 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Empe ...

and Alexei Khvostov

Aleksey Nikolayevich Khvostov () (1 July 1872 – 23 August 1918) was a right-wing Russian politician and the leader of the Russian Assembly. He was a governor, a Privy Councillor (Russia), a chamberlain, a member of the Black Hundreds, and ant ...

.

Assassination

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings that an assassination plot was afoot as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , there was a performance of

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings that an assassination plot was afoot as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , there was a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

's ''The Tale of Tsar Saltan'' at the Kiev Opera House in the presence of the Tsar and his two oldest daughters, the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana

Tatiana (or Tatianna, also romanized as Tatyana, Tatjana, Tatijana, etc.) is a female name of Sabine-Roman origin that became widespread in Eastern Europe.

Variations

* be, Тацця́на, Tatsiana

* bg, Татяна, Tatyana

* germ ...

. The theater was occupied by 90 men posted as interior guards. According to Alexander Spiridovich

Alexander Ivanovich Spiridovich (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Спиридо́вич; 1873–1952) was a police general in the Russian Imperial Guard. He became a historian after he had left Russia.

Life

Spiridovitch was bor ...

, after the second act "Stolypin was standing in front of the ramp separating the parterre from the orchestra, his back to the stage. On his right were Baron Freedericks and Gen. Sukhomlinov." His personal bodyguard had stepped out to smoke. Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the chest, by Dmitry Bogrov

Dmitry Grigoriyevich Bogrov ( – ) () was the assassin of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.

On Bogrow was sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on in the Kiev fortress Lyssa Hora.

Stolypin's widow had campaigned in vain to spare the ass ...

, a Jewish leftist revolutionary. Bogrov ran to one of the entrances and was caught. Stolypin rose from his chair, removed his gloves and unbuttoned his jacket, exposing a blood-soaked waistcoat. He gave a gesture to tell the Tsar to go back and made the sign of the cross. He never lost consciousness, but his condition deteriorated. He died four days later.

Bogrov was hanged 10 days after the assassination. The judicial investigation was halted by order of the Tsar, giving rise to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists who were afraid of Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the Tsar. However, this has never been proven. On his request, Stolypin was buried in the city where he was murdered.

Legacy

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by revolutionary unrest and discontent was widespread among the population. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by revolutionary unrest and discontent was widespread among the population. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

, that allowed for the arrest and speedy trial of accused offenders. Over 3,000 (possibly 5,500) suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. In a Duma session on 17 November 1907, Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

party member referred to the gallows as "Stolypin's efficient black Monday necktie". As a result, Stolypin challenged Rodichev to a duel, but the Kadet party member decided to apologize for the phrase in order to avoid the duel. Nevertheless, the expression remained, as did the phrase "Stolypin car

Stolypin car (russian: Столыпинский вагон, Stolypinskiy vagon) is a type of railroad carriage in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union, and modern Russia.

During the Stolypin reform in Russia around the turn of the century, which gave ...

".

The opinions on Stolypin's work are divided. Some hold that, in the unruly atmosphere after the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, he had to suppress violent revolt and anarchy. However, historians disagree over how realistic Stolypin's policies were. Others, however, have argued that, while it is true that the conservatism of most peasants prevented them from embracing progressive change, Stolypin was correct in thinking that he could "wager on the strong" since there was indeed a layer of strong peasant farmers. This argument is based on evidence drawn from tax returns data, which shows that a significant minority of peasants were paying increasingly higher taxes from the 1890s, a sign that their farming was producing higher profits.

There remains doubt whether, even without the interruption of Stolypin's murder and the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, his agricultural policy would have succeeded. The deep conservatism from the mass of peasants made them slow to respond. In 1914 the strip system was still widespread, with only around 10% of the land having been consolidated into farms.Lynch, Michael ''From Autocracy to Communism: Russia 1894-1941'' p.42 Most peasants were unwilling to leave the security of the commune for the uncertainty of individual farming. Furthermore, by 1913, the government's own Ministry of Agriculture had itself begun to lose confidence in the policy. Nevertheless, Krivoshein became the most powerful figure in the Imperial government.

Published in the Paris newspaper "Social-Democrat" on 31 October 1911, in an article titled "Stolypin and the Revolution", Lenin, calling for the "mortification of the uber-lyncher", said:

″Stolypin tried to pour new wine into old bottles, to reshape the old autocracy into a bourgeois monarchy; and the failure of Stolypin's policy is the failure of tsarism on this last, the last conceivable, road for tsarism."

In " Name of Russia", a 2008 television poll to select "the greatest Russian", Stolypin placed second, behind Alexander Nevsky and followed by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

. He is seen by his admirers as the greatest statesman Russia ever had, the one who could have saved the country from revolution and the civil war.

On 27 December 2012, a monument to Pyotr Stolypin was unveiled in Moscow to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth. The monument is situated near the Russian White House

The White House ( rus, Белый дом, r=Bely dom, p=ˈbʲɛlɨj ˈdom; officially The House of the Government of the Russian Federation, rus, Дом Правительства Российской Федерации, r=Dom pravitelstva Ross ...

where the Russian Cabinet is situated. At the foot of the pedestal, a bronze plaque has written on it a well-known expression of Stolypin: ''"We must all unite in defense of Russia, coordinate our efforts, our duties and our rights in order to maintain one of Russia's historic supreme rights - to be strong."''

Screen portrayals

Stolypin is portrayed in the opening scenes of the 1971 British film ''Nicholas and Alexandra

''Nicholas and Alexandra'' is a 1971 British epic historical drama film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, from a screenplay written by James Goldman and Edward Bond, based on Robert K. Massie's 1967 book of the same name, which is a partia ...

'', anachronistically taking part in the Romanov dynasty tercentenary celebrations of 1913 before being assassinated later in the film, two years after the date of his actual assassination.

See also

* Coup of June 1907 *Stolypin reform

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted during the tenure of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Most, if not all, of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known ...

References

Further reading

* * Conroy, M.S. (1976), ''Peter Arkadʹevich Stolypin: Practical Politics in Late Tsarist Russia'', Westview Press, (Boulder), 1976. * Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 314. . * * Lieven, Dominic, ed. ''The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 2, Imperial Russia, 1689-1917'' (2015) * * * Pallot, Judith. ''Land reform in Russia, 1906-1917: peasant responses to Stolypin's project of rural transformation'' (1999)online

* Pares, Bernard. ''A History of Russia'' (1926) pp 495–506

Online

* Pares, Bernard. '' The Fall of the Russian Monarchy'' (1939) pp 94–143

Online

*

External links

* *Stolypin and the Russian Agrarian Miracle

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stolypin, Petr 1862 births 1911 deaths 1911 murders in Europe 20th-century murders in Russia Marshals of nobility Heads of government of the Russian Empire Interior ministers of Russia Assassinated politicians of the Russian Empire Deaths by firearm in Russia People murdered in Russia Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Assassinated heads of government Burials at the Refectory Church, Kyiv Pechersk Lavra People from Dresden Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Male murder victims Russian duellists Russian untitled nobility Russian monarchists