Petition of Right on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to

Charles instructed the

Charles instructed the

Despite being unanimously accepted by the Commons on 3 April, the Resolutions had no legal power and were rejected by Charles. He presented an alternative; a bill confirming ''Magna Carta'' and six other liberty-related statutes, on condition it contained "no enlargement of former bills". The Commons refused, since Charles was only confirming established rights, which he had already shown willing to ignore, while it would still allow him to decide what was legal.

After conferring with his supporters, Charles announced Parliament would be

Despite being unanimously accepted by the Commons on 3 April, the Resolutions had no legal power and were rejected by Charles. He presented an alternative; a bill confirming ''Magna Carta'' and six other liberty-related statutes, on condition it contained "no enlargement of former bills". The Commons refused, since Charles was only confirming established rights, which he had already shown willing to ignore, while it would still allow him to decide what was legal.

After conferring with his supporters, Charles announced Parliament would be

Charles' acceptance was greeted with widespread public celebrations, including ringing of church bells and lighting of bonfires throughout the country. However, in August, Buckingham was assassinated by a disgruntled former soldier, while the surrender of La Rochelle in October effectively ended the war, and Charles' need for taxes. He dissolved Parliament in 1629, ushering in eleven years of Personal Rule, in which he attempted to regain all the ground lost.

For the rest of his reign, Charles used the same tactics; refusing to negotiate until forced, with concessions seen as temporary and reversed as soon as possible, by force if needed. Once Parliament adjourned, he resumed the policy of imposing unauthorised taxes, then prosecuting opponents using the non-jury

Charles' acceptance was greeted with widespread public celebrations, including ringing of church bells and lighting of bonfires throughout the country. However, in August, Buckingham was assassinated by a disgruntled former soldier, while the surrender of La Rochelle in October effectively ended the war, and Charles' need for taxes. He dissolved Parliament in 1629, ushering in eleven years of Personal Rule, in which he attempted to regain all the ground lost.

For the rest of his reign, Charles used the same tactics; refusing to negotiate until forced, with concessions seen as temporary and reversed as soon as possible, by force if needed. Once Parliament adjourned, he resumed the policy of imposing unauthorised taxes, then prosecuting opponents using the non-jury

Digital Reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petition Of Right 1628 in England 1628 in law 17th century in England Acts of the Parliament of England Acts of the Parliament of England still in force Constitution of the United Kingdom Constitutional laws of England Constitution of New Zealand 1628 works Political charters

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

and the Bill of Rights 1689. It was part of a wider conflict between Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

and the Stuart monarchy that led to the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

, ultimately resolved in the 1688 Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

.

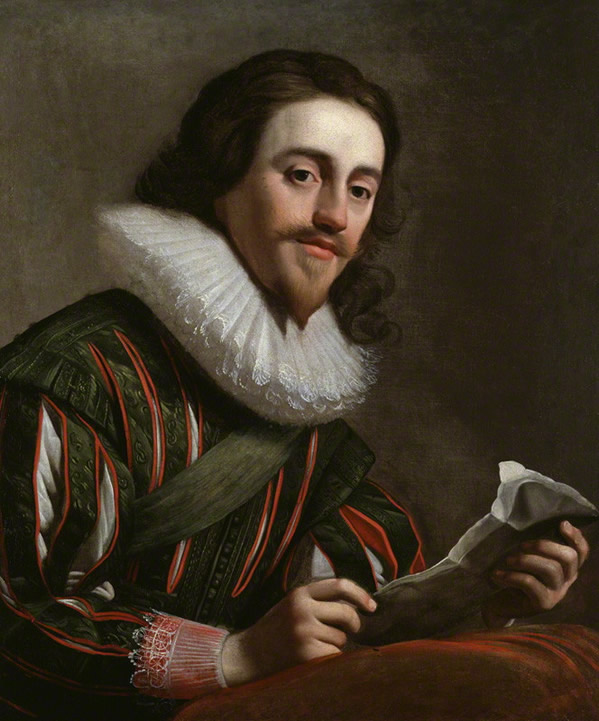

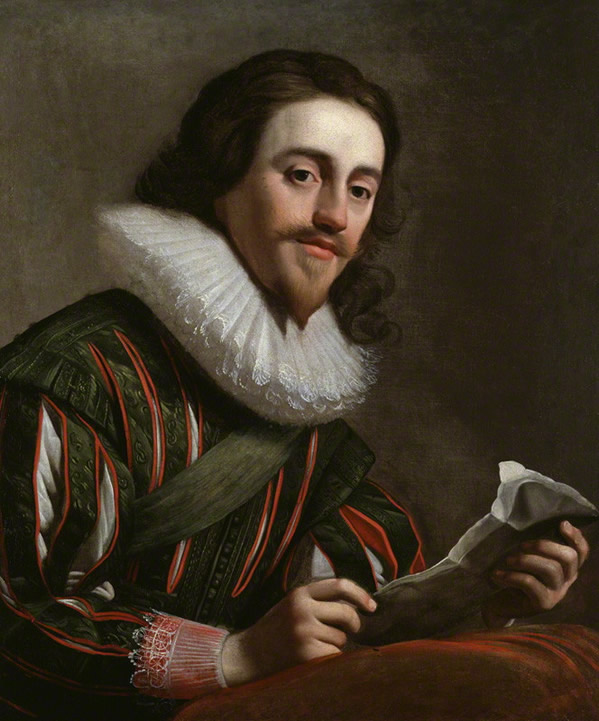

Following a series of disputes with Parliament over granting taxes, in 1627 Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

imposed "forced loans", and imprisoned those who refused to pay, without trial. This was followed in 1628 by the use of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

, forcing private citizens to feed, clothe and accommodate soldiers and sailors, which implied the king could deprive any individual of property, or freedom, without justification. It united opposition at all levels of society, particularly those elements the monarchy depended on for financial support, collecting taxes, administering justice etc, since wealth simply increased vulnerability.

A Commons committee prepared four "Resolutions", declaring each of these illegal, while re-affirming Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

and ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

''. Charles previously depended on the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

for support against the Commons, but their willingness to work together forced him to accept the Petition. It marked a new stage in the constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this ...

, since it became clear many in both Houses did not trust him, or his ministers, to interpret the law.

The Petition remains in force in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and parts of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. It reportedly influenced elements of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties, and the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hi ...

, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh amendments to the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

.

Background

On 27 March 1625,James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

died, and was succeeded by his son, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. His most pressing foreign policy issue was the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, particularly regaining the hereditary lands and titles of the Protestant Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V (german: link=no, Friedrich; 26 August 1596 – 29 November 1632) was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate bo ...

, who was married to his sister Elizabeth.

The pro- Spanish policy pursued by James prior to 1623 had been unpopular, inefficient and expensive, and there was widespread support for declaring war. However, money granted by Parliament for this purpose was spent on the royal household, while they also objected to the use of indirect taxes and customs duties. Charles' first Parliament wanted to review the entire system, and as a temporary measure while doing so, the Commons granted Tonnage and Poundage for twelve months, rather than the entire reign, as was customary.

Charles instructed the

Charles instructed the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

to reject the bill, and adjourned Parliament on 11 July, but needing money for the war, recalled it on 1 August. However, the Commons began investigating Charles' favourite and military commander, the Duke of Buckingham, notorious for inefficiency and extravagance. When they demanded his impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

in return for approving taxes, Charles dissolved his first parliament on 12 August 1625. The disastrous Cádiz expedition forced him to recall Parliament in 1626, but once again they demanded the impeachment of Buckingham before providing funds to finance the war, Charles adopted "forced loans"; those who refused to pay would be imprisoned without trial, and if they continued to resist, sent before the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

.

Ruled illegal by Chief Justice Sir Randolph Crewe

Sir Ranulph (or Ralulphe, Randolph, or Randall) Crew(e) (1558 – 3 January 1646) was an English judge and Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Early life and career

Ranulph Crewe was the second son of John Crew of Nantwich, who is said to hav ...

, the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

complied only after he was dismissed. Over 70 individuals were jailed for refusing to contribute, including Sir Thomas Darnell, Sir John Corbet, Sir Walter Erle, Sir John Heveningham

Sir John Heveningham (c. 1577 – 17 June 1633) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1628 to 1629.

Life

Heveningham was the son of Sir Arthur Heveningham, of Heveningham, Suffolk and was baptised there on 26 March 1577 ...

and Sir Edmund Hampden, who submitted a joint petition for ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

''. Approved on 3 November 1627, the court ordered the five be brought before them for examination. Since it was unclear what they were charged with, the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Sir Robert Heath

Sir Robert Heath (20 May 1575 – 30 August 1649) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1621 to 1625.

Early life

Heath was the son of Robert

Heath, attorney, and Anne Posyer. He was educated at Tunbridg ...

attempted to get a ruling; this became known as ' Darnell's Case', although Darnell himself withdrew.

The judges avoided the issue by denying bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

, on the grounds that as there were no charges, "the risonerscould not be freed, as the offence was probably too dangerous for public discussion". A clear defeat, Charles decided not to pursue charges; since his opponents included the previous Chief Justice, and other senior legal officers, the ruling meant the loans would almost certainly be deemed illegal. So many now refused payment, the reduction in projected income forced him to recall Parliament in 1628, while the controversy returned "a preponderance of MPs opposed to the King".

To fund his army, Charles resorted to martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

. This was a process employed for short periods by his predecessors, specifically to deal with internal rebellions, or imminent threat of invasion, clearly not the case here. Intended to allow local commanders to try soldiers or insurgents outside normal courts, it was now extended to require civilians to feed, house and clothe military personnel, known as 'Coat and conduct money.' As with forced loans, this deprived individuals of personal property, subject to arbitrary detention if they protested.

In a society that valued stability, predictability, and conformity, the parliament assembled in March claimed to be confirming established and customary law, implying both James and Charles had attempted to alter it. On 1 April, a Commons committee began preparing four resolutions, led by Sir Edward Coke

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as ...

, a former Chief Justice, and most respected lawyer of the age. One protected individuals from taxation not authorised by Parliament, like forced loans, the other three summarised rights in place since 1225, and later enshrined in the Habeas Corpus Act 1679. They stipulated individuals could not be imprisoned without trial, deprived of ''habeas corpus'', whether by king or Privy Council, or detained until charged with a crime.

Passage

Despite being unanimously accepted by the Commons on 3 April, the Resolutions had no legal power and were rejected by Charles. He presented an alternative; a bill confirming ''Magna Carta'' and six other liberty-related statutes, on condition it contained "no enlargement of former bills". The Commons refused, since Charles was only confirming established rights, which he had already shown willing to ignore, while it would still allow him to decide what was legal.

After conferring with his supporters, Charles announced Parliament would be

Despite being unanimously accepted by the Commons on 3 April, the Resolutions had no legal power and were rejected by Charles. He presented an alternative; a bill confirming ''Magna Carta'' and six other liberty-related statutes, on condition it contained "no enlargement of former bills". The Commons refused, since Charles was only confirming established rights, which he had already shown willing to ignore, while it would still allow him to decide what was legal.

After conferring with his supporters, Charles announced Parliament would be prorogued

A legislative session is the period of time in which a legislature, in both parliamentary and presidential systems, is convened for purpose of lawmaking, usually being one of two or more smaller divisions of the entire time between two election ...

on 13 May, but was now out-manoeuvred by his opponents. Since he refused a public bill, Coke suggested the Commons and Lords pass the resolutions as a Petition of Right, and then have it "exemplified under the great seal". An established element of Parliamentary procedure, this had not been expressly prohibited by Charles, allowing them to evade his restrictions, but avoid direct opposition.

The Committee redrafted the content as a 'Petition', which was accepted by the Commons on 8 May, and presented the same day to the Lords by Coke, with a bill approving subsidies to encourage acceptance. After several days of debate, they approved it, but attempted to "sweeten" the wording; they then received a message from Charles, claiming he must retain the right to decide whether to detain someone.

Despite protestations on both sides, in an age when legal training was considered part of a gentleman's education, significant elements within both Commons and Lords did not trust Charles to interpret the law. The Commons ignored both the request, and alterations proposed by the Lords to appease him; by now, there was a clear majority in both houses for the Petition as originally submitted. On 26 May, the Lords unanimously voted to join with the Commons on the Petition of Right, with the minor addition of an assurance of their loyalty, approved by the Commons on 27 May.

Charles now ordered John Finch, the Speaker of the Commons, to prevent "insult", or criticism of any Minister of State. He specifically named Buckingham, and in response, Selden moved the Commons demand his removal from office. Needing money for his war effort, Charles finally accepted the Petition, but first increased the level of mistrust on 2 June by trying to qualify it. Both houses now demanded "a clear and satisfactory answer by His Majesty in full Parliament", and on 7 June, Charles capitulated.

Provisions

After setting out a list of individual grievances and statutes that had been broken, the Petition of Right declares that Englishmen have various "rights and liberties", and provides that no person should be forced to provide a gift, loan or tax without an Act of Parliament, that no free individual should be imprisoned or detained unless a cause has been shown, and that soldiers or members of theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

should not be billeted in private houses without the free consent of the owner.

In relation to martial law, the Petition first repeated the due process chapter of ''Magna Carta'', then demanded its repeal. This clause was directly addressed to the various commissions issued by Charles and his military commanders, restricting the use of martial law except in war or direct rebellion and prohibiting the formation of commissions. A state of war automatically activated martial law; as such, the only purpose for commissions, in their view, was to unjustly permit martial law in circumstances that did not require it.

Aftermath

Charles' acceptance was greeted with widespread public celebrations, including ringing of church bells and lighting of bonfires throughout the country. However, in August, Buckingham was assassinated by a disgruntled former soldier, while the surrender of La Rochelle in October effectively ended the war, and Charles' need for taxes. He dissolved Parliament in 1629, ushering in eleven years of Personal Rule, in which he attempted to regain all the ground lost.

For the rest of his reign, Charles used the same tactics; refusing to negotiate until forced, with concessions seen as temporary and reversed as soon as possible, by force if needed. Once Parliament adjourned, he resumed the policy of imposing unauthorised taxes, then prosecuting opponents using the non-jury

Charles' acceptance was greeted with widespread public celebrations, including ringing of church bells and lighting of bonfires throughout the country. However, in August, Buckingham was assassinated by a disgruntled former soldier, while the surrender of La Rochelle in October effectively ended the war, and Charles' need for taxes. He dissolved Parliament in 1629, ushering in eleven years of Personal Rule, in which he attempted to regain all the ground lost.

For the rest of his reign, Charles used the same tactics; refusing to negotiate until forced, with concessions seen as temporary and reversed as soon as possible, by force if needed. Once Parliament adjourned, he resumed the policy of imposing unauthorised taxes, then prosecuting opponents using the non-jury Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the ju ...

. When Parliament and the normal courts quoted the Petition in support of objections to the tax, and the detention of Selden and Sir John Eliot

Sir John Eliot (11 April 1592 – 27 November 1632) was an English statesman who was serially imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he eventually died, by King Charles I for advocating the rights and privileges of Parliament.

Early life

T ...

, Charles responded it was not a legal document.

Although confirmed as a legal statute in 1641 by the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

, debate over who was right continues; however, "it seems impossible to establish conclusively which interpretation (is) correct". Regardless, the Petition has been described as "one of England's most famous constitutional documents", of equal standing to ''Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

'' and the 1689 Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

. It remains in force in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and much of the Commonwealth. It has been cited in support of the Third Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Third Amendment (Amendment III) to the United States Constitution places restrictions on the quartering of soldiers in private homes without the owner's consent, forbidding the practice in peacetime. The amendment is a response to the Quar ...

, and the Seventh. It is suggested elements appear in the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Amendment, primarily through the Massachusetts Body of Liberties.

References

Note

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Digital Reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petition Of Right 1628 in England 1628 in law 17th century in England Acts of the Parliament of England Acts of the Parliament of England still in force Constitution of the United Kingdom Constitutional laws of England Constitution of New Zealand 1628 works Political charters