Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pennsylvania Hall, "one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city," was an

Pennsylvania Hall Association Records

held a

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

African-American history in Philadelphia History of Philadelphia History of women in Pennsylvania Abolitionism in the United States Women's rights in the Americas Riots and civil disorder in Philadelphia White American riots in the United States American proslavery activists Arson in Pennsylvania May 1838 events Buildings and structures in Philadelphia Buildings and structures in the United States destroyed by arson Origins of the American Civil War American anti-abolitionist riots and civil disorder Demolished buildings and structures in Philadelphia

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

venue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, built in 1837–38. It was a "Temple of Free Discussion", where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Four days after it opened it was destroyed by arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

, the work of an anti-abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

mob. Except for the burning of the White House and the Capitol during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, it was the worst case of arson in American history up to that date.

This was only six months after the murder of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterianism, Presbyterian Minister (Christianity), minister, journalist, Editing, newspaper editor, and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. Followin ...

by a pro-slavery mob in Illinois, a free state. The abolitionist movement consequently became stronger. The process repeated itself with Pennsylvania Hall; the movement gained strength because of the outrage the burning caused. Abolitionists realized that in some places they would be met with violence. The country became more polarized.

Building name and purpose

Located at 109 N. Sixth Street, the site was "symbolically and strategically ideal". It was near where the United States was born, where theDeclaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

and the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

were created. It was also in the middle of the Philadelphia Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

community, so active in the beginnings of the abolition of slavery and in aiding fugitives

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also kno ...

.

The inspiration for the building, to the extent there was one, was Temperance Hall, also in downtown Philadelphia, at 538–40 N. Third St. It seated 300–600, and was the venue for various lectures and debates. Many organizations, including abolitionist groups, held meetings there in the 1830s, "with n anti-abolitionistcrowd at one time determined to burn the place down."

Considering the organization that built it, the offices and stores located there, and the meetings held during the four days of its use, the new building was clearly intended to have an abolitionist focus. But to name it "Abolition Hall" would have been reckless and provocative. "Pennsylvania Hall" was a neutral alternative. "The Board of Managers took pains to make clear that the hall was not exclusively for the use of abolitionists. It was to be open on an equal basis for rental by any groups 'for any purpose not of an immoral character'."

Construction

The Hall was built by thePennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society

The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society was established in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1838. Founders included James Mott, Lucretia Mott, Robert Purvis, and John C. Bowers.

In August 1850, William Still while working as a clerk for the Society, ...

"because abolitionists had such a difficult time finding space for their meetings". The building was designed by architect Thomas Somerville Stewart; it was his first major building.

To finance construction a joint-stock company was created. Two thousand people bought $20 shares, raising over $40,000. Others donated material and labor.

Description of the building

On the ground floor were four stores or offices, which fronted on Sixth St. One was an abolitionist reading room and bookstore; another held the office of the ''Pennsylvania Freeman

The ''National Enquirer'' was an abolitionist newspaper founded by Quaker Benjamin Lundy in 1836,Wicks, Suzanne RBenjamin Lundy. Friends Journal

'', John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

's newly-reincarnated abolitionist newspaper. Another held the office of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, the building's manager, and the fourth was devoted to the sale of products grown or produced without slave labor ( free produce).

The first floor also contained "a neat lecture room" seating between 200 and 300 persons, fronting on Haines Street. There were two committee rooms and three large entries and stairways wide leading to the second floor.

On the second floor there was a large auditorium, with three galleries, on the third floor, surrounding it, "seating all told perhaps as many as three thousand persons. The building was ventilated through the roof, so fresh air could be obtained without opening the windows. It was lighted with gas. The interior appointments were luxurious." Above the stage was a banner with Pennsylvania's motto

A motto (derived from the Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. Mot ...

, "Virtue, Liberty, and Independence".

In the basement, because of the weight of the press and type, was to be the press for the Society's abolitionist newspaper, the ''National Enquirer and General Register'', which had been edited by Benjamin Lundy

Benjamin Lundy (January 4, 1789August 22, 1839) was an American Quaker abolitionist from New Jersey of the United States who established several anti-slavery newspapers and traveled widely. He lectured and published seeking to limit slavery's expa ...

, but with the move Lundy's successor, John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

, took over as editor, and the name changed to ''Pennsylvania Freeman

The ''National Enquirer'' was an abolitionist newspaper founded by Quaker Benjamin Lundy in 1836,Wicks, Suzanne RBenjamin Lundy. Friends Journal

''. However, the press had not yet been moved at the time of the fire, and thus escaped destruction.

Destruction of the building planned in advance

The following is from aletter to the editor

A letter to the editor (LTE) is a Letter (message), letter sent to a publication about an issue of concern to the reader. Usually, such letters are intended for publication. In many publications, letters to the editor may be sent either through ...

signed "J. A. G.", published in a New York newspaper on May 30:

The Mayor of Philadelphia had advance knowledge of an "organized band" prepared to disrupt the meeting and "perhaps do injury to the building":

Timeline

Meetings were being held in the building before its formal opening on May 14. Throughout the ceremonies, blacks and whites sat in the audience without separation, and except for those meetings specifically for women, men and women did as well. Such a heterogenous audience had never existed in Philadelphia before. In addition, women and blacks spoke to mixed audiences, which was for some a delight and for others a threat to social order.Monday, May 14, 1838

* 10 AM: "The President f the Associationwill take the chair at 10 o'clock precisely. The Secretary will then read a short statement of the monies which induced the stockholders to erect the building, and the purposes for which it is to be used. Also several interesting letters from individuals at distance." Letters from philanthropistGerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

, abolitionist organizer Theodore Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known ...

, and former president John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

were read. Ohio Senator Thomas Morris was invited in January to speak at the dedication, but was unable to attend, and also sent a letter to be read.

Adams' letter read, in part:I learnt with great satisfaction...that the Pennsylvania Hall Association have erected a large building in your city, wherein liberty and equality of civil rights can be freely discussed, and the evils of slavery fearlessly portrayed. ...I rejoice that, in the city of Philadelphia, the friends of free discussion have erected a Hall for its unrestrained exercise."After which, David Paul Brown of this city .html" ;"title="counsellor at law"">counsellor at law"will deliver an Oration upon Liberty." * "In the afternoon the Philadelphia Lyceum will meet at 3 o'clock, when an ''Essay upon the Lyceum system of Instruction, showing its advantages, mode of operation, &c.,'' written by Victor Value, of Philadelphia, will be read. At 3 o'clock, James P. Espy, of Philad., will explain the cause of winds, clouds, storms, and other atmospheric phenomena. At 4 o'clock several interesting questions will be read and referred to different members of the Lyceum for solution at their meeting on Tuesday afternoon. This meeting will conclude with a discussion on the question—Which has the greater influence, Wealth or Knowledge?" The debate will be opened by two members of the Lyceum—after which any member or visitor may participate. The meeting will adjourn at 6 o'clock." The Lyceum, "so that it should not appear to be in any way connected with the benevolent institution known by the name of the Anti-Slavery Society", requested that the Pennsylvania Hall Association not publish the proceedings of their Monday and Tuesday afternoon meetings. * "''Evening meeting'' at 8 o'clock. Lecture upon Temperance, by Thomas P. Hunt, of South Carolina, preceded by a short address from Arnold Buffum, of Pniladelphia, on the same subject." " me person in the vicinity threw a brickbat through the window and blind." * In the evening, at the house of Ann R. Frost, the bride's sister, there took place "what was, among abolitionists at least, the wedding of the century", "an abolition wedding":

Angelina Grimké

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (February 20, 1805 – October 26, 1879) was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were c ...

married Theodore Dwight Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known ...

. (They had met in an abolition training session.) Present were William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

, Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan (May 23, 1788 – June 21, 1873) was a New York abolitionist who worked to achieve freedom for the enslaved Africans aboard the '' Amistad''. Tappan was also among the founders of the American Missionary Association in 1846, which ...

, Henry B. Stanton

Henry Brewster Stanton (June 27, 1805 – January 14, 1887) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, social reformer, Lawyer, attorney, journalist and politician. His writing was published in the ''New York Tribune, ...

, Henry C. Wright

Henry Clarke Wright (August 29, 1797 – August 16, 1870) was an American abolitionist, pacifist, anarchist and feminist, for over two decades a controversial figure.

Early life

Clarke was born in Sharon, Connecticut, to father Seth Wright, a ...

, Maria Weston Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery jour ...

, James G. Birney, Abby Kelley

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and radical social Reform movement#United States reform movements of the 1840s – 1930s, reformer active from the 1830s ...

, Sarah Mapps Douglass

Sarah Mapps Douglass (September 9, 1806 – September 8, 1882) was an American educator, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, writer, and public lecturer. Her painted images on her written letters may be the first or earliest survivi ...

, the bride's sister Sarah Grimké

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pi ...

, and two former slaves of the Grimké family, whose freedom Ann had purchased. The cake was made by a Black confectioner, using free produce sugar. Both a Black and a White minister gave blessings; the Black one was Theodore S. Wright

Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1797–1847), sometimes Theodore Sedgewick Wright, was an African-American abolitionist and minister who was active in New York City, where he led the First Colored Presbyterian Church as its second pastor. He was ...

.

Tuesday, May 15

* At 10 AM the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held a preliminary meeting in "the session roon"; theGrimké sisters

Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily GrimkéUnited States. National Park Service. "Grimke Sisters." U.S. Department of the Interior, October 8, 2014. Accessed:October 14, 2014. (1805–1879), known as the Grimké sisters, were th ...

, Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

, Maria Weston Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery jour ...

, Susan Paul

Susan Paul (1809–1841) was an African-American abolitionist from Boston, Massachusetts. A primary school teacher and member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Paul also wrote the first biography of an African American published in t ...

, Sarah Mapps Douglass

Sarah Mapps Douglass (September 9, 1806 – September 8, 1882) was an American educator, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, writer, and public lecturer. Her painted images on her written letters may be the first or earliest survivi ...

, Juliana Tappan, eldest daughter of philanthropist and abolition activist Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan (May 23, 1788 – June 21, 1873) was a New York abolitionist who worked to achieve freedom for the enslaved Africans aboard the '' Amistad''. Tappan was also among the founders of the American Missionary Association in 1846, which ...

, and others from as far as Maine were in attendance.

*In the "Grand Saloon", Pennsylvania Representative Walter Forward

Walter Forward (January 24, 1786 – November 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and politician. He was the brother of Chauncey Forward.

Biography

Born in East Granby, Connecticut, he attended the common schools. After moving with his father to ...

, who was to have talked on "the right of Free Discussion", and Ohio Senator Thomas Morris did not appear as announced. James Burleigh

James Burleigh (24 February 1869 – 1917) was an English footballer who played as an outside left for Wolverhampton Wanderers in the Football League

The English Football League (EFL) is a league of professional association football, footb ...

read, at Whittier's request, a lengthy "poetical address" by John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

, who was present. Local abolitionist Lewis C. Gunn spoke at length extemporaneously, followed by Burleigh talking about Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

, and Alvin Stewart about the Seminoles

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and ...

. (May 23 was the deadline for the removal of Native Americans on the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

from Florida, Georgia, and other Southern states to the future Oklahoma.) In response to audience requests, Garrison, "who had not been invited to speak in Philadelphia since 1835", rose to attack the speech of Brown (for not rejecting "colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

"), followed by Burleigh and Stewart, who criticized both Brown and colonization. "With no end to the debate in sight and the Lyceum members waiting to use the room", Samuel Webb announced that the debate, on abolitionism versus colonization, announced for the following week. would take place the next morning.

* The Lyceum met in the afternoon, considering "the history, present condition, and future prospects of the human mind", and "whether opposition or approbation from others provided greater proof of a man's merit."

* At 4 PM, again in the session room, the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women set up a committee to prepare an agenda ("business"). The following day, they were to meet in Temperance Hall.

*"We herewith enclose a written piacard, numbers of which were posted up in various parts of the city, and, so far as we have seen, all appeared to be in the same hand writing."

Wednesday, May 16

* The annual meeting of the Pennsylvania State Anti-Slavery Society "for the Eastern District" had been announced for 10 AM but it met instead at 8 AM, to allow a debate on abolition versus colonization to take place. They adjourned until 2 PM. * In the Grand Saloon, a large crowd gathered to hear the debate on colonization versus abolitionism. No one showed up to make the case for colonization, so those for abolition proceeded to discuss "Slavery and its Remedy". *About 50 to 60 people gathered outside, making occasional threats against the attendees. The group grew throughout the day, using increasingly abusive language. The building managers hired two watchmen to keep the peace. *That evening,William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

introduced Maria Weston Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery jour ...

to an audience of 3,000 abolitionists. The mob outside grew violent, smashing windows and breaking into the meeting. Despite the turmoil, Angelina Grimké Weld convinced the audience to stay with an hour-long speech. To protect their more vulnerable members, the group of whites and blacks left the gathering, whites and blacks arm-in-arm, through a hail of rocks and jeers.

Thursday, May 17

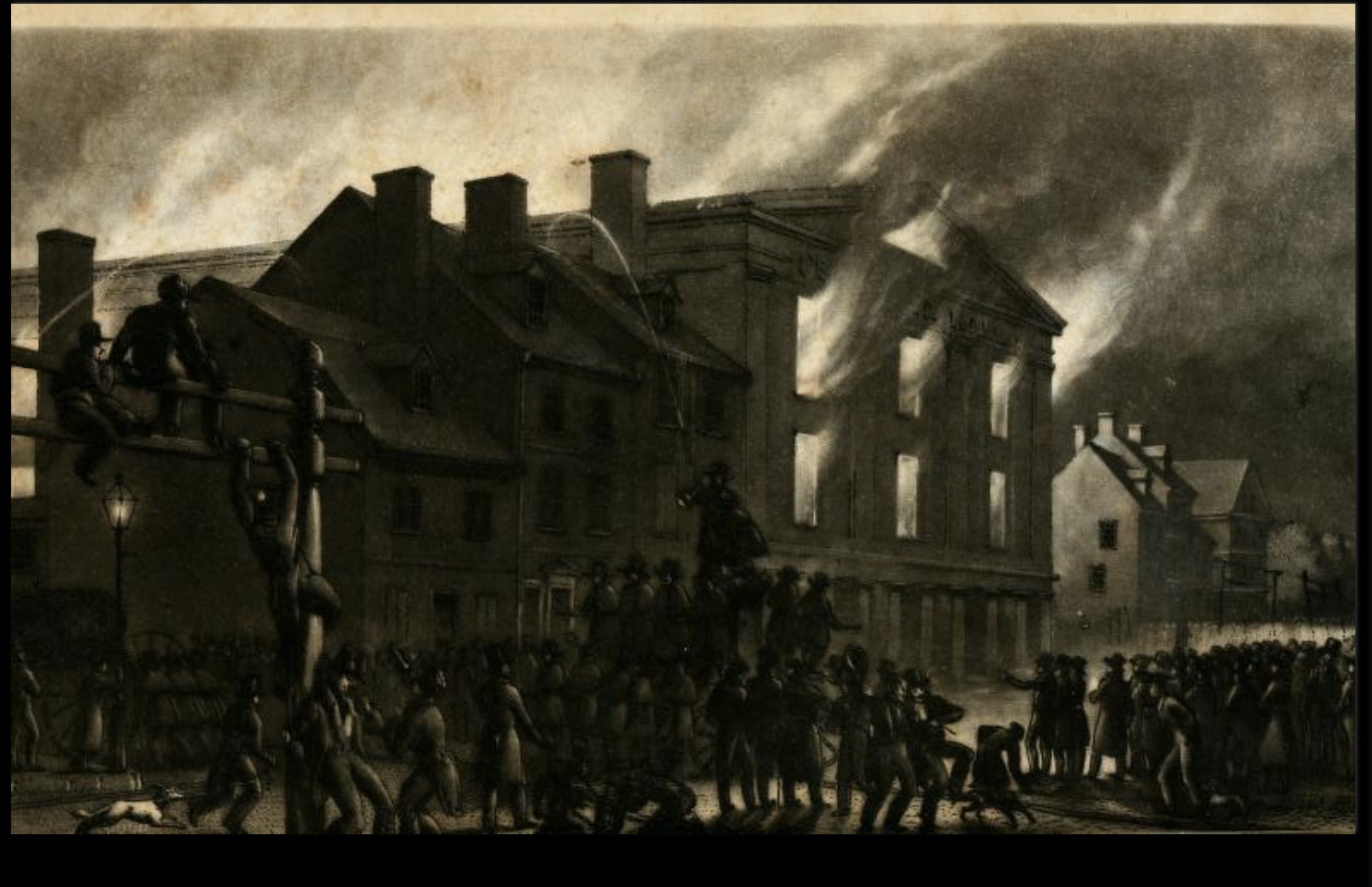

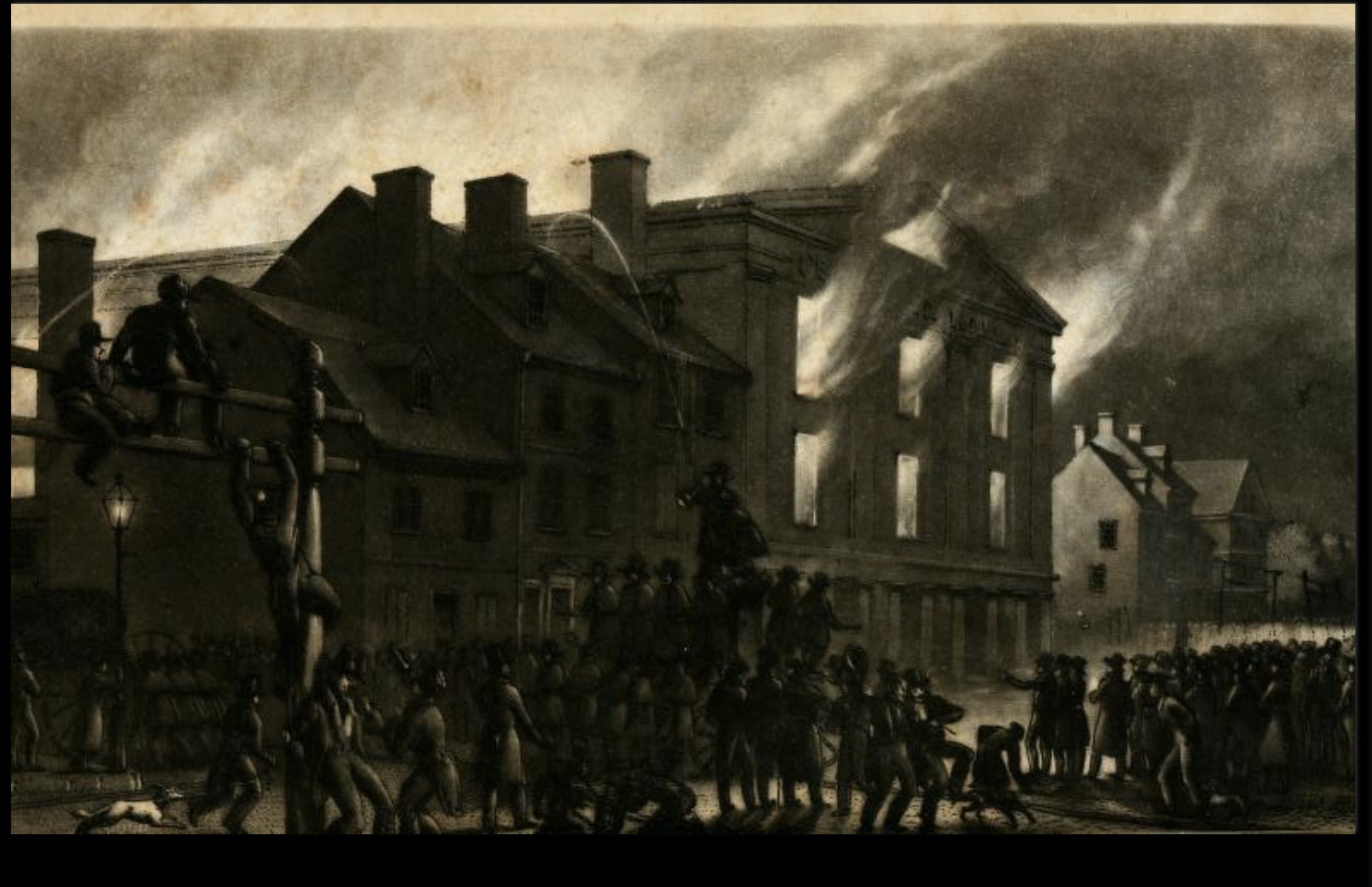

* The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met again in the main room of the hall, having met in Temperance Hall on Wednesday. They "refused to comply with the Mayor's request to restrict the meeting to white women only." * A Requited (paid, non-slave) Labor Convention, whose purpose was to create a National Requited Labor Association, met in a session room at 8 AM and in the Grand Saloon at 2 PM. (See Free-produce movement.) * Managers met and decided to write letters to the mayor and the sheriff requesting protection. Three went to meet with the mayor, advised him of the situation, showed him the placard, and offered to "give him the name of one of the ringleaders of the mob". "The mayor gave little indication that he wanted to intervene. ...He said 'There are always two sides to a question — it is public opinion make mobs — and ninety-nine out of a hundred of those with whom I converse are against you.'" He said that in the evening he would address the crowd, but could do nothing further. * The Wesleyan Antislavery Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church of Philadelphia was to meet in the evening. * "On the 17th, early in the evening, the managers, at the request of John Swift, Mayor of the city, closed the Hall and delivered the keys to him — he having advised the abstaining from holding an evening meeting, as a necessary means for ensuring the safety of the building." * "A large mob was assembled and was every moment increasing. The Mayor having taken the key, addressed the crowd in deferential language; and recommending to them to go home and go to bed, as he intended to do, he wished them 'a hearty good night', and left the ground amid the cheers of the assemblage. About half an hour afterwards, the doors were forced by the mob, and the Hall was set on fire, with little apparent resistance from the police." "No attempt of any kind was made to quell the riot", wrote an eyewitness. * "The fire engines of the city repaired to the spot, and by their efforts protected the surrounding buildings. Many of the firemen were not disposed to extinguish the fire in the Hall, and some who attempted it were deterred by threats of violence." The firemen did not try to save the hall, but concentrated on saving the adjacent structures. "When one unit tried spraying the new building, its men became the target of the other units' hoses." As put in a letter from an eyewitness to the New Orleans '' True American'': * "The papers say that of the many thousands, who crowded in the vicinity to witness the conflagration of this beautiful edifice, the larger part were 'respectable and well dressed persons, who evidently looked on with approbation.' ...It is said that when the roof of this noble temple of liberty fell in there was a universal shout of triumph."Friday, May 18

* The following meetings had been announced for Friday: "To-morrow the State Anti-Slavery Society will meet at 8 o'clock, A.M. The Free Produce Convention at 10 o'clock. The Convention of American Women will meet at 1 o'clock, P.M. and the Free Produce Convention will meet at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, and the Pennsylvania State Anti Slavery Society will meet at 8 o'clock in the evening." On Monday the 21st there was to have been a debate between abolitionists and colonizationists. * The attendees of the Requited Labor Convention assembled "at the ruins of the Pennsylvania Hall" and adjourned to the residence ofJames Mott

James Mott (20 June 1788 – 26 January 1868) was a Quaker leader, teacher, merchant, and anti-slavery activist. He was married to suffragist leader Lucretia Mott.

Life and work

James was born in Cow Neck in North Hempstead on Long Island, t ...

, where a committee was set up to find a place for future meetings.

* " e next night, the 18th, a body of entire strangers to the locality attacked and set fire to the Friends' charitable institution, called the Shelter for Colored Children, in Thirteenth Street above Callowhill, and considerably damaged the building before the fire was extinguished." It "was with difficulty preserved from utter conflagration by the spirited conduct of the firemen and the police magistrate of the district."

Saturday, May 19

* "And the next evening, the 19th, Bethel Church, in South Sixth Street, belonging to colored people, was attacked and sustained injury.". "This would have shared the fate of Pennsylvania Hall, had not the Recorder of the city, with a spirit which does him great credit, interfered to do what the Mayor should have done on the first day, and forming a guard of well disposed citizens around the building, awed the rioters from their meditated violence." * "From regulating the affairs of the church the mob proceeded to extend its cares to the public press. The ''Philadelphia Ledger

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

'' had displeased it by the freedom of some of its remarks on the right of mobs to insult women and destroy property, and the office of the ''Philadelphia Ledger'' was accordingly doomed to destruction." However, no attack on it took place.

Aftermath

The burning was greatly praised in Southern newspapers. A Northern newspaper, defending slavery, blamed the riot on the abolitionists.Rewards

The mayor of Philadelphia, John Swift, offered a $2000 reward, and the Governor of Pennsylvania,Joseph Ritner

Joseph Ritner (March 25, 1780 – October 16, 1869) was the eighth Governor of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and was a member of the Anti-Masonic Party. Elected Governor of Pennsylvania during the 1835 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, h ...

, offered $500. Samuel Yaeger, described as "a man of considerable property, and the father of five children", was arrested. He is presumably the arrested "individual of good standing" who was observed "busily engaged in tearing down the blinds, and inciting others to the destruction of the building." Another man was arrested with him. Other arrests were made, but there were no trials, much less convictions, and the rewards were never claimed.

Investigation of the mayor and police

The mayor of Philadelphia, John Swift, received a lot of criticism in the press. In the end, the city's official report blamed the fire and riots on the abolitionists, saying they had upset the citizens by encouraging "race mixing" and inciting violence.Role of the sheriff

The Sheriff of Philadelphia County, John G. Watmough, in his report to the Governor, said: "I arrested with my own hands some ten or a dozen rioters; among them a sturdy blackguard engaged in forcing the doors with a log of wood, and a youth with a brand of fire in his hands. They were either forcibly rescued from me or were let loose again by those into whose hands I gave them. I appealed in vain for assistance — no one responded to me." However, "many individuals are already in custody". Just after the burning a new fund was set up by the Philadelphia Hall Society to raise $50,000 with which to rebuild. Nothing further was heard of this attempt.Efforts to recover damages from the city

All sources agree that since it was destroyed by a mob, the city was financially responsible for the building's damages, according to a recent law. After many years and much litigation the Anti-Slavery Society was able to recover a part of the loss from the city.National impact

"Ultimately the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall contributed to an awakening by the Northern public that was essential to the defeat of slavery." "The gutted shell stood for several years after the blaze, becoming a pilgrimage site for abolitionists." "In the destruction of this Hall consecrated to freedom, a fire has in fact been kindled that will never go out. The onward progress of our cause in the Key-stone State may now be regarded as certain." "The Philadelphia '' Public Ledger'', which was threatened with demolition by the rioters in the late mob, asserts that its daily circulation has augmented nearly two thousand since the disturbances, notwithstanding its uncompromising opposition to mobs."Primary sources

* * * * * Also published as a pamphlet, . * *Legacy

* "The Tocsin", by Rev.John Pierpont

John Pierpont (April 6, 1785 – August 27, 1866) was an American poet, who was also successively a teacher, lawyer, merchant, and Unitarian minister. His poem '' The Airs of Palestine'' made him one of the best-known poets in the U.S. in his da ...

, on occasion of the Hall's destruction, was published anonymouslty in ''The Liberator'' of May 25.

Historical marker

In 1992, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission erected a marker at the Hall's location. The marker reads: "Built on this site in 1838 by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society as a meeting place for abolitionists, this hall was burned to the ground by anti-Black rioters three days after it was first opened."See also

* Lombard Street riot (1842) * Philadelphia Nativist Riots (1844)Further reading

* * * * *References

{{ReflistExternal links

Pennsylvania Hall Association Records

held a

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

African-American history in Philadelphia History of Philadelphia History of women in Pennsylvania Abolitionism in the United States Women's rights in the Americas Riots and civil disorder in Philadelphia White American riots in the United States American proslavery activists Arson in Pennsylvania May 1838 events Buildings and structures in Philadelphia Buildings and structures in the United States destroyed by arson Origins of the American Civil War American anti-abolitionist riots and civil disorder Demolished buildings and structures in Philadelphia