Pavel Miliukov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

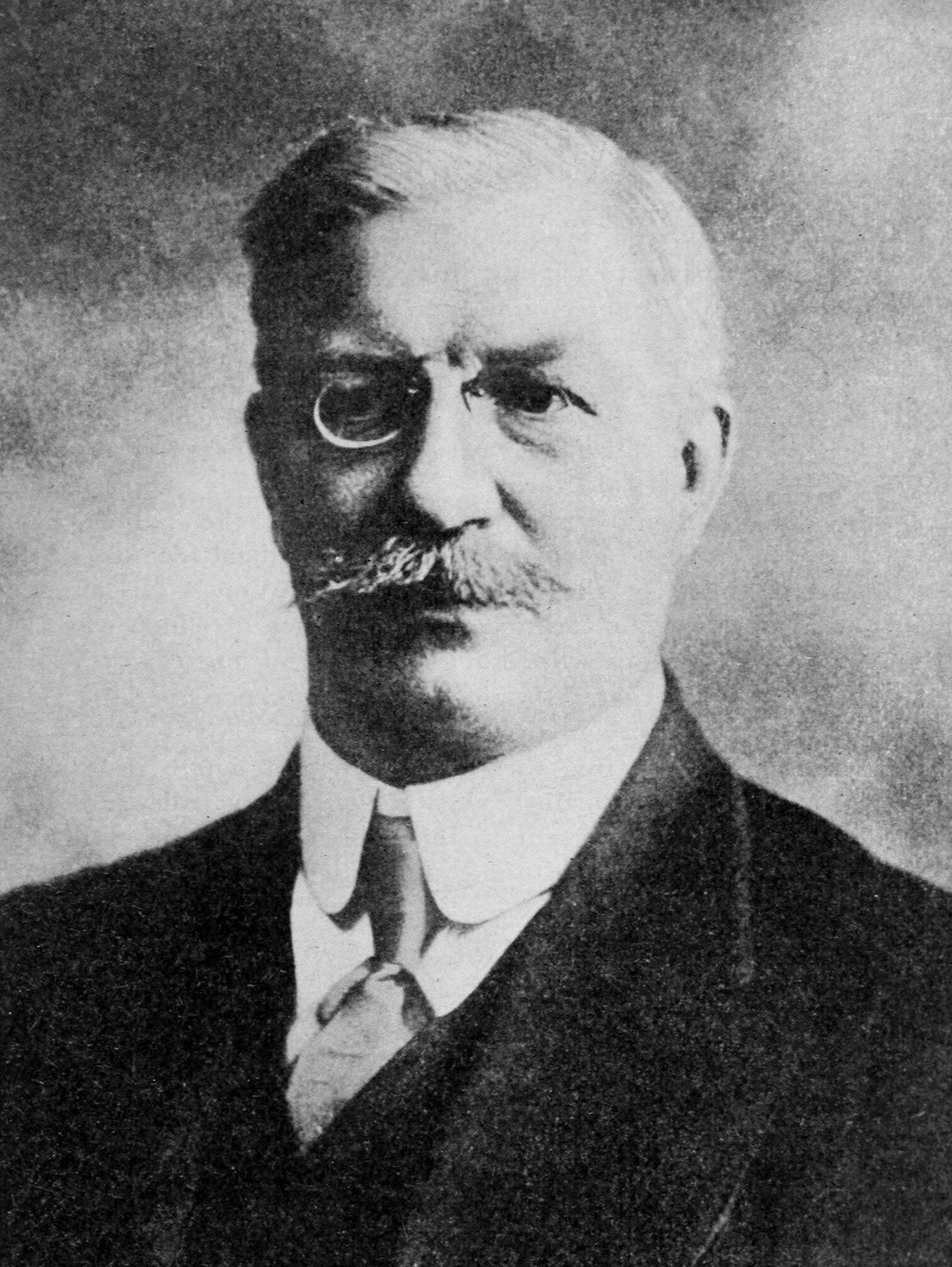

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, –Я–∞ћБ–≤–µ–ї –Э–Є–Ї–Њ–ї–∞ћБ–µ–≤–Є—З –Ь–Є–ї—О–Ї–ЊћБ–≤, p=m ≤…™l ≤ КЋИkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the

In 1890 he became a member of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities. He gave private lectures with great success at a training institute for girl teachers and in 1895 was appointed to the university. These lectures were afterward expanded by him in his book ''Outlines of Russian Culture'' (3 vols., 1896вАУ1903, translated into several languages). He started an association for "home university reading," and, as its first president, edited the first volume of its program, which was widely read in Russian intellectual circles. As a student Milyukov was influenced by the liberal ideas of

In 1890 he became a member of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities. He gave private lectures with great success at a training institute for girl teachers and in 1895 was appointed to the university. These lectures were afterward expanded by him in his book ''Outlines of Russian Culture'' (3 vols., 1896вАУ1903, translated into several languages). He started an association for "home university reading," and, as its first president, edited the first volume of its program, which was widely read in Russian intellectual circles. As a student Milyukov was influenced by the liberal ideas of

At Progressive Bloc meetings near the end of October, Progressives and left-Kadets argued that the revolutionary public mood could no longer be ignored and that the Duma should attack the entire tsarist system or lose whatever influence it had. Nationalists feared that a concerted stand against the government would jeopardize the existence of the Duma and further inflame the revolutionary feelings. Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking

At Progressive Bloc meetings near the end of October, Progressives and left-Kadets argued that the revolutionary public mood could no longer be ignored and that the Duma should attack the entire tsarist system or lose whatever influence it had. Nationalists feared that a concerted stand against the government would jeopardize the existence of the Duma and further inflame the revolutionary feelings. Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking

During the February Revolution Milyukov hoped to retain the

During the February Revolution Milyukov hoped to retain the

On 26 October 1917, the party's newspapers were shut down by the new Soviet Government.

On 25 November 1917 Milyukov was elected in the

On 26 October 1917, the party's newspapers were shut down by the new Soviet Government.

On 25 November 1917 Milyukov was elected in the

Russia and its crisis (1905)

by P.N. Miliukov

Constitutional government for Russia

an address delivered before the Civic forum by P.N. Miliukov. New York city, 14 January 1908 (1908) * "Past and present of Russian economics" in ''Russian realities & problems: Lectures delivered at Cambridge in August 1916'', by Pavel Milyukov, Peter Struve, Harold Williams, Alexander Lappo-Danilevsky and

Bolshevism: an international danger

by P.N. Miliukov. 1920. * History of the Second Russian Revolution (1921) by P. Milykov.

Russia, to-day and to-morrow (1922)

by P.N. Miliukov.

online

* Breuillard, Sabine. "Russian LiberalismвАФUtopia or Realism? The Individual and the Citizen in the Political Thought of Milyukov." in Robert B Mcklean, ed. ''New Perspectives in Modern Russian History'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1992) pp. 99вАУ116. * Elkin, B. I. "Paul Milyukov (1859вАУ1943)" ''Slavonic and East European Review'' 23#2 (1945), pp. 137вАУ14

online obituary

* Jansen, Dinah. "After October: Russian Liberalism as a 'Work in Progress,' 1919-1945," Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada (2015). * Pearson, Raymond. "Milyukov and the Sixth Kadet Congress." ''Slavonic and East European Review'' 53.131 (1975): 210вАУ229

online

* Riha, Thomas. ''A Russian European: Paul Miliukov in Russian Politics'', (U of Notre Dame Press, 1969), , 373pp. * Stockdale, Melissa Kirschke. ''Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia, 1880вАУ1918'', (Cornell University Press, 1996), , 379pp. * Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." ''Slavonic & East European Review'' 93.2 (2015): 315вАУ337

online

* Zeman, ZbynƒЫk A. ''A diplomatic history of the First World War.'' (1971) pp 207вАУ42.

an early critique of Miliukov's liberalism by

Constitutional Democratic party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (russian: –Ъ–Њ–љ—Б—В–Є—В—Г—Ж–Є–ЊћБ–љ–љ–Њ-–і–µ–Љ–Њ–Ї—А–∞—В–ЄћБ—З–µ—Б–Ї–∞—П –њ–∞ћБ—А—В–Є—П, translit=Konstitutsionno-demokraticheskaya partiya, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of P ...

(known as the ''Kadets''). He changed his view on the monarchy between 1905 and 1917. In the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, –Т—А–µ–Љ–µ–љ–љ–Њ–µ –њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В–µ–ї—М—Б—В–≤–Њ –†–Њ—Б—Б–Є–Є, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

, he served as Foreign Minister, working to prevent Russia's exit from the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

Pre-revolutionary career

Pavel was born in Moscow in the upper-class family of Nikolai Pavlovich Milyukov, a professor in architecture who taught at theMoscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture

The Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (russian: –Ь–Њ—Б–Ї–Њ–≤—Б–Ї–Њ–µ —Г—З–Є–ї–Є—Й–µ –ґ–Є–≤–Њ–њ–Є—Б–Є, –≤–∞—П–љ–Є—П –Є –Ј–Њ–і—З–µ—Б—В–≤–∞, –Ь–£–Ц–Т–Ч) also known by the acronym MUZHZV, was one of the largest educational insti ...

. Milyukov was a member of the House of Milukoff. Milyukov studied history and philology at the Moscow University

M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU; russian: –Ь–Њ—Б–Ї–Њ–≤—Б–Ї–Є–є –≥–Њ—Б—Г–і–∞—А—Б—В–≤–µ–љ–љ—Л–є —Г–љ–Є–≤–µ—А—Б–Є—В–µ—В –Є–Љ–µ–љ–Є –Ь. –Т. –Ы–Њ–Љ–Њ–љ–Њ—Б–Њ–≤–∞) is a public research university in Moscow, Russia and the most prestigious ...

, where he was influenced by Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 вАУ 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

, Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste Fran√Іois Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 вАУ 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

, and Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 вАУ 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

. His teachers were Vasily Klyuchevsky

Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky (russian: –Т–∞—Б–Є–ї–Є–є –Ю—Б–Є–њ–Њ–≤–Є—З –Ъ–ї—О—З–µ–≤—Б–Ї–Є–є; in Voskresnskoye Village, Penza Governorate, Russia вАУ , Moscow) was a leading Russian Imperial historian of the late imperial period. Also, he addres ...

and Paul Vinogradoff

Sir Paul Gavrilovitch Vinogradoff (russian: –Я–∞ћБ–≤–µ–ї –У–∞–≤—А–ЄћБ–ї–Њ–≤–Є—З –Т–Є–љ–Њ–≥—А–∞ћБ–і–Њ–≤, transliterated: ''Pavel Gavrilovich Vinogradov''; 18 November 1854 (O.S.)19 December 1925) was a Russian and British historian and medieval ...

. In summer 1877 he briefly took part in Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or OttomanвАУRussian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

as a military logistic, but returned to the university. He was expelled for taking part in student riots, went to Italy, but was readmitted and allowed to take his degree. He specialized in the study of Russian history and in 1885 received the degree for work on the ''State Economics of Russia in the First Quarter of the 18th Century and the reforms of Peter the Great

Peter I ( вАУ ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Aleks√©yevich ( rus, –Я—С—В—А –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–µћБ–µ–≤–Є—З, p=ЋИp ≤…µtr …Рl ≤…™ЋИks ≤ej…™v ≤…™t…Х, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

''.

In 1890 he became a member of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities. He gave private lectures with great success at a training institute for girl teachers and in 1895 was appointed to the university. These lectures were afterward expanded by him in his book ''Outlines of Russian Culture'' (3 vols., 1896вАУ1903, translated into several languages). He started an association for "home university reading," and, as its first president, edited the first volume of its program, which was widely read in Russian intellectual circles. As a student Milyukov was influenced by the liberal ideas of

In 1890 he became a member of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities. He gave private lectures with great success at a training institute for girl teachers and in 1895 was appointed to the university. These lectures were afterward expanded by him in his book ''Outlines of Russian Culture'' (3 vols., 1896вАУ1903, translated into several languages). He started an association for "home university reading," and, as its first president, edited the first volume of its program, which was widely read in Russian intellectual circles. As a student Milyukov was influenced by the liberal ideas of Konstantin Kavelin

Konstantin Dmitrievich Kavelin (russian: –Ъ–Њ–љ—Б—В–∞–љ—В–ЄћБ–љ –Ф–Љ–ЄћБ—В—А–Є–µ–≤–Є—З –Ъ–∞–≤–µћБ–ї–Є–љ; November 4, 1818 вАУ May 5, 1885) was a Russian historian, jurist, and sociologist, sometimes called the chief architect of early Russian lib ...

and Boris Chicherin

Boris Nikolayevich Chicherin (russian: –С–Њ—А–ЄћБ—Б –Э–Є–Ї–Њ–ї–∞ћБ–µ–≤–Є—З –І–Є—З–µћБ—А–Є–љ) ( 1828 вАУ 1904) was a Russian jurist and political philosopher, who worked out a theory that Russia needed a strong, authoritative government to perseve ...

. His liberal opinions brought him into conflict with the educational authorities, and he was dismissed in 1894 after one of the ever-recurrent university "riots". He was imprisoned for two years in Riazan as a political agitator, but contributed as an archaeologist.

When released from jail, Milyukov went to Bulgaria, and was appointed professor in the University of Sofia

Sofia University, "St. Kliment Ohridski" at the University of Sofia, ( bg, –°–Њ—Д–Є–є—Б–Ї–Є —Г–љ–Є–≤–µ—А—Б–Є—В–µ—В вАЮ–°–≤. –Ъ–ї–Є–Љ–µ–љ—В –Ю—Е—А–Є–і—Б–Ї–ЄвАЬ, ''Sofijski universitet вАЮSv. Kliment OhridskiвАЬ'') is the oldest higher education i ...

, where he lectured in Bulgarian in the philosophy of history

Philosophy of history is the philosophical study of history and its discipline. The term was coined by French philosopher Voltaire.

In contemporary philosophy a distinction has developed between ''speculative'' philosophy of history and ''crit ...

, etc. He was sent (or dismissed under Russian pressure) to Macedonia, part of the Ottoman Empire. There he worked in an archaeological site. In 1899 he was allowed to return to St Petersburg. In 1901 he was arrested again for taking part in a commemoration of the populist writer Pyotr Lavrov

Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov (russian: –Я—С—В—А –Ы–∞ћБ–≤—А–Њ–≤–Є—З –Ы–∞–≤—А–ЊћБ–≤; alias Mirtov (); (June 14 O.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="une 2 Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 1823 вАУ February 6 anuary 6 O.S. 1900) was a ...

. (The last volume of ''Outlines of Russian Culture'' was actually finished in jail, where he spent six months for his political speech.) In 1901, according to Milyukov, about 16,000 people were exiled from the capital. The following by-law, published in 1902 by the governor of Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''–С–µ—Б—Б–∞—А–∞ћБ–±—Ц—П'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

is typical:

He contributed under a pseudonym to the clandestine journal ''Liberation'', founded by Peter Berngardovich Struve, published in Stuttgart in 1902. The government again gave him the choice of exile for three years or jail for six months, Milyukov chose the Kresty Prison

Kresty (russian: –Ъ—А–µ—Б—В—Л, literally ''Crosses'') prison, officially Investigative Isolator No. 1 of the Administration of the Federal Service for the Execution of Punishments for the city of Saint Petersburg (–°–ї–µ–і—Б—В–≤–µ–љ–љ—Л–є –Є–Ј–Њ– ...

. After an interview with Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, –Т—П—З–µ—Б–ї–∞ћБ–≤ (Wenzel (–°–ї–∞–≤–Є–Ї)) –Є–Ј –Я–ї–µ–≤–љ—Л –Ъ–Њ–љ—Б—В–∞–љ—В–ЄћБ–љ–Њ–≤–Є—З —Д–Њ–љ –Я–ї–µћБ–≤–µ, p=v ≤…™t…Х…™ЋИslaf f…Рn ЋИpl ≤ev ≤…™; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

, whom he regarded as "the symbol of the Russia he hated", Milyukov was released. He was central in the founding of the Union of Unions in 1905.

In 1903 he delivered courses of lectures in the United States вАКat summer sessions in University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and for the Lowell Institute lectures in Boston. He visited London and attended the Paris Conference 1904, organized by the Finnish dissident Konni Zilliacus. Milyukov returned to Russia during the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, according to Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes () is a British historian and writer. Until his retirement, he was Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Figes is known for his works on Russian history, such as '' A People's Tragedy'' (1996), ''Nata ...

in many ways a foretaste of the conflicts of 1917. He founded the Constitutional Democratic party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (russian: –Ъ–Њ–љ—Б—В–Є—В—Г—Ж–Є–ЊћБ–љ–љ–Њ-–і–µ–Љ–Њ–Ї—А–∞—В–ЄћБ—З–µ—Б–Ї–∞—П –њ–∞ћБ—А—В–Є—П, translit=Konstitutsionno-demokraticheskaya partiya, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of P ...

, a party of professors, academics, lawyers, writers, journalists, teachers, doctors, officials, and liberal zemstvo

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, –Ј–µ–Љ—Б—В–≤–Њ, p=ЋИz ≤…Ыmstv…Щ, plural ''zemstva'' вАУ rus, –Ј–µ–Љ—Б—В–≤–∞) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexande ...

men. As a journalist for "Svobodny narod" ("Free People") and "Narodnaya swoboda" ("People's Freedom") or as a former political prisoner Milyukov was not allowed to represent the Kadets in the first and second Duma

A duma (russian: –і—Г–Љ–∞) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were f ...

. For Milyukov any agreement between liberalism and autocracy was impossible. In 1906 the Duma was dissolved and its members moved to Vyborg

Vyborg (; rus, –Т—ЛћБ–±–Њ—А–≥, links=1, r=V√љborg, p=ЋИv…®b…Щrk; fi, Viipuri ; sv, Viborg ; german: Wiborg ) is a town in, and the administrative center of, Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus ...

in Finland. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto

The Vyborg Manifesto (russian: –Т—Л–±–Њ—А–≥—Б–Ї–Њ–µ –≤–Њ–Ј–Ј–≤–∞–љ–Є–µ, translit=Vyborgskoye Vozzvaniye, fi, Viipurin manifesti, sv, Viborgsmanifestet); also called the Vyborg Appeal) was a proclamation signed by several Russian politicians, pri ...

, calling for political freedom, reforms, and passive resistance to the governmental policy.

Dmitri Trepov

Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov (transliterated at the time as Trepoff) (15 December 1850 вАУ 15 September 1906) was Head of the Moscow police, Governor-General of St. Petersburg with extraordinary powers, and Assistant Interior Minister with full contr ...

suggested Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (russian: –Ш–≤–∞ћБ–љ –Ы√≥–≥–≥–Є–љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –У–Њ—А–µ–Љ—ЛћБ–Ї–Є–љ, Iv√°n L√≥gginovich Gorem√љkin) (8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 a ...

ought to step down and promote a cabinet with only Kadets, which in his opinion would soon enter into a violent conflict with the Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

and fail. He secretly met with Milyukov. Trepov opposed Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, –Я—С—В—А –Р—А–Ї–∞ћБ–і—М–µ–≤–Є—З –°—В–Њ–ї—ЛћБ–њ–Є–љ, p=p ≤…µtr …РrЋИkad ≤j…™v ≤…™t…Х st…РЋИl…®p ≤…™n; вАУ ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third prime minister and the interior ministe ...

, who promoted a coalition cabinet

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

.

The Kadets gave up the idea of founding a republic and promoting a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Russia, prime minister of Russian Provisional Government, republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During ...

and Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–∞ћБ–љ–і—А –Ш–≤–∞ћБ–љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –У—Г—З–Ї–ЊћБ–≤) (14 October 1862 вАУ 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

...

tried to convince the tsar to accept liberals in the new government. In 1907 Milyukov was elected in the Third Duma; at some time he joined the board of the party Rech (newspaper)

''Rech'' (; current Russian: –†–µ—З—М, originally: –†—£—З—М) was a Russian daily newspaper and the central organ of the Constitutional Democratic Party.

History

''Rech'' was published in St. Petersburg from February 1906 to October 1917. Julia ...

. He was one of the few publicists in Russia, who had considerable knowledge of international politics, and his articles on the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, „Ф„Ю„Ц„®„Ч „Ф„І„®„Х„С; arc, №Х№Ґ№Ъ№Р №©№™№Т; fa, ЎЃЎІўИЎ± ўЖЎ≤ЎѓџМЏ©, XƒБvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakƒ±n DoƒЯu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

seem to be of considerable interest.

Deputy

In January 1908 Milyukov addressed "The Civic Forum" inCarnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th and 57th Streets. Designed by architect William Burnet Tuthill and built ...

. From the very beginning, the slogan and the idea of the empire ruled by Russians were very controversial regarding what "Russians" meant. One of the outspoken critics of the notion, Pavel Milyukov, considered the "Russia for Russians

"Russia for Russians" (russian: –†–Њ—Б—Б–ЄћБ—П –і–ї—П —А—ГћБ—Б—Б–Ї–Є—Е, ''Rossiya dlya russkikh'', ) is a political slogan and nationalist doctrine, encapsulating the range of ideas from bestowing the ethnic white Russians with exclusive rights in ...

" slogan to have been "a slogan of disunity... ndnot creative but destructive." In 1909, Milyukov addressed the Russian State Duma on the issue of using Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

in the court system, attacking Russian nationalist deputies: "You say "Russia for Russians," but whom do you mean by "Russian"? You should say "Russia only for the Great Russia

Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' (russian: –Т–µ–ї–Є–Ї–∞—П –†—Г—Б—М, , , , , ), is a name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of Muscovy and later Russia. This was the land to which the et ...

ns," because that which you do not give to Muslims and Jews you also do not give your own nearest kin вАУ Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, –£–Ї—А–∞—Ч–љ–∞, Ukra√ѓna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

."

In 1912 he was reelected in the Fourth Duma. According to Milyukov, in May 1914 Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, –У—А–Є–≥–Њ—А–Є–є –Х—Д–Є–Љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –†–∞—Б–њ—Г—В–Є–љ ; вАУ ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus ga ...

had become an influential factor in Russian politics. With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Milyukov swung to the right, but a coup to remove the Tsar belonged to the possibilities. He had become a nationalist, patriotic policy of national defense, relying on social chauvinism

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

. (He was best friends with Sergei Sazonov

Sergei Dmitryevich Sazonov GCB (Russian: –°–µ—А–≥–µ–є –Ф–Љ–Є—В—А–Є–µ–≤–Є—З –°–∞–Ј–Њ–љ–Њ–≤; 10 August 1860 in Ryazan Governorate 11 December 1927) was a Russian statesman and diplomat who served as Foreign Minister from November 1910 to July 1916 ...

.) Milyukov insisted his younger son volunteer for the army (who subsequently died in battle). In August 1915 he formed the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Span ...

and became the leader. Milyukov was regarded as a staunch supporter of the conquest of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, ўВЎ≥ЎЈўЖЎЈўКўЖўКўЗ

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. In the nineties, Milyukov thoroughly studied the Balkans, which made him the most competent authority on Balkan politics. His opponents mockingly called him "Milyukov of Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, √Зanakkale BoƒЯazƒ±, lit=Strait of √Зanakkale, el, ќФќ±ѕБќіќ±ќљќ≠ќїќїќєќ±, translit=Dardan√©llia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

". In Summer 1916, at the request of Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: –Ь–Є—Е–∞–ЄћБ–ї –Т–ї–∞–і–ЄћБ–Љ–Є—А–Њ–≤–Є—З –†–Њ–і–Ј—ПћБ–љ–Ї–Њ; uk, –Ь–Є—Е–∞–є–ї–Њ –Т–Њ–ї–Њ–і–Є–Љ–Є—А–Њ–≤–Є—З –†–Њ–і–Ј—П–љ–Ї–Њ; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beo ...

, Protopopov Protopopov is the surname of several Russian individuals.

*Alexander Protopopov (1866вАУ1918), Russian Minister of Interior 1916вАУ17

* Mikhail Protopopov (1848вАУ1915), Russian journalist and literary critic

*Oleg Protopopov

Oleg Alekseyevich ...

led a delegation of Duma members (with Milyukov) to strengthen the ties with Russia's western allies in World War I: the ( Entente powers). In August he gave lectures in Oxford. On 1 November 1916, in a populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

speech, he sharply criticized the St√Љrmer government for its inefficiency. He met professor Thomas Garrigue Masaryk in London, and consulted with him about the present state of the Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion (Czech language, Czech: ''ƒМeskoslovensk√© legie''; Slovak language, Slovak: ''ƒМeskoslovensk√© l√©gie'') were volunteer armed forces composed predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Allies of World ...

in Russia at that time.

"Stupidity or treason" speech

At Progressive Bloc meetings near the end of October, Progressives and left-Kadets argued that the revolutionary public mood could no longer be ignored and that the Duma should attack the entire tsarist system or lose whatever influence it had. Nationalists feared that a concerted stand against the government would jeopardize the existence of the Duma and further inflame the revolutionary feelings. Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking

At Progressive Bloc meetings near the end of October, Progressives and left-Kadets argued that the revolutionary public mood could no longer be ignored and that the Duma should attack the entire tsarist system or lose whatever influence it had. Nationalists feared that a concerted stand against the government would jeopardize the existence of the Duma and further inflame the revolutionary feelings. Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking Boris St√Љrmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (russian: –С–Њ—А–ЄћБ—Б –Т–ї–∞–і–ЄћБ–Љ–Є—А–Њ–≤–Є—З –®—В—ОћБ—А–Љ–µ—А) (27 July 1848 вАУ 9 September 1917) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a ...

and forcing his replacement.

According to Stockdale, he had trouble gaining the support of his own party; at the 22вАУ24 October Kadet fall conference provincial delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity. His travels abroad had made him poorly informed about the public mood, they charged; the patience of the people was exhausted." He responded with a plea to keep their ultimate goal in mind:It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905.The day before the opening of the Duma, the Progressist party pulled out of the bloc because they believed the situation called for more than a mere denunciation of St√Љrmer. On 1 November (O.S.) the government under the pro-peace Boris St√Љrmer was attacked in the Imperial Duma, not gathering since February.

Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( вАУ 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Novem ...

spoke first, called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka r GrigoriRasputin!" The acting president Rodzianko ordered him to leave, when calling for the overthrow of the government in wartime. Miliukov's speech was more than three times longer than Kerensky's, and delivered using much more moderate language.

In his speech "Rasputin and Rasputuiza" he spoke of "treachery and betrayal, about the dark forces, fighting in favor of Germany". He highlighted numerous governmental failures, including the case Sukhomlinov, concluding that St√Љrmer's policies placed in jeopardy the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. After each accusation вАУ many times without basis вАУ he asked "Is this stupidity or is it treason?" and the listeners answered "stupidity!", "treason!", etc. (Milyukov stated that it did not matter "Choose any ... as the consequences are the same.") St√Љrmer walked out, followed by all his ministers.

He began by outlining how public hope had been lost over the course of the war, saying: "We have lost faith that the government can lead us to victory." He mentioned the rumours of treason and then proceeded to discuss some of the allegations: that St√Љrmer had freed Suchomlinov, that there was a great deal of pro-German propaganda, that he had been told that the enemy had access to Russian state secrets in his visits to allied countries and that St√Љrmer's private secretary van Manuilov-Manasevichhad been arrested for taking German bribes but was released when he kicked back to St√Љrmer.

Milyukov was taken immediately by Sir George Buchanan to the British Embassy and lived there till the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, –§–µ–≤—А–∞ћБ–ї—М—Б–Ї–∞—П —А–µ–≤–Њ–ї—ОћБ—Ж–Є—П, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=f ≤…™vЋИral ≤sk…Щj…Щ r ≤…™v…РЋИl ≤uts…®j…Щ), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

; (according to Stockdale he went to the Crimea). It is not known what they discussed, but his speech was spread in flyers on the front and at the Hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associate ...

. St√Љrmer and Protopopov asked in vain for the dissolution of the Duma. Tsarina Alexandra suggested to her husband to expel Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–∞ћБ–љ–і—А –Ш–≤–∞ћБ–љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –У—Г—З–Ї–ЊћБ–≤) (14 October 1862 вАУ 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

...

, Prince Lvov

Lvov (russian: –Ы—М–≤–Њ–≤) is the name of a princely Russian family of Rurikid stock. The family is descended from the princes of Yaroslavl where early members of the family are buried.

Notable members

*Knyaz Matvey Danilovich (?вАУ1603), Voivod ...

, Milyukov and Alexei Polivanov to Siberia.

According to Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, it was a "volatile combination of revolutionary passions, escalating apprehension, and the near breakdown of unity in the moderate camp that provided the impetus for the most notorious address in the history of the Duma..." The speech was a milestone on the road to Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, –У—А–Є–≥–Њ—А–Є–є –Х—Д–Є–Љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –†–∞—Б–њ—Г—В–Є–љ ; вАУ ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus ga ...

's murder and the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, –§–µ–≤—А–∞ћБ–ї—М—Б–Ї–∞—П —А–µ–≤–Њ–ї—ОћБ—Ж–Є—П, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=f ≤…™vЋИral ≤sk…Щj…Щ r ≤…™v…РЋИl ≤uts…®j…Щ), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

. Stockdale also points out that Miliukov admitted to some reservations about his evidence in his memoirs, where he observed that his listeners resolutely answered ''treason'' "even in those aspects where I myself was not entirely sure."

Richard Abraham, in his biography of Kerensky, argues that the withdrawal of the Progressists was essentially a vote of no confidence in Miliukov and that he grasped at the idea of accusing St√Љrmer in an effort to preserve his own influence.

February Revolution

During the February Revolution Milyukov hoped to retain the

During the February Revolution Milyukov hoped to retain the constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

in Russia. He became a member of the Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under th ...

on 27 February 1917. Milyukov wanted the monarchy retained, albeit with Alexei as Tsar and the Grand Duke Michael acting as Regent. When Michael awoke on 2 March (O.S.), he discovered not only that his brother had abdicated in his favour, as Nicholas had not informed him previously, but also that a delegation from the Duma would visit him in a few hours. The meeting with Duma President Rodzianko, Prince Lvov

Lvov (russian: –Ы—М–≤–Њ–≤) is the name of a princely Russian family of Rurikid stock. The family is descended from the princes of Yaroslavl where early members of the family are buried.

Notable members

*Knyaz Matvey Danilovich (?вАУ1603), Voivod ...

, and other ministers, including Milyukov and Kerensky, lasted all morning. Since the masses would not tolerate a new Tsar and the Duma could not guarantee Michael's safety, Michael decided to decline the throne. On 6 March 1917, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 вАУ 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

gave a cautious welcome to the suggestion of Milyukov that the toppled Tsar and his family could be given sanctuary in Britain, but Lloyd George would have preferred that they go to a neutral country.

Rodzianko succeeded in publishing an order for the immediate return of the soldiers to their barracks, subordinate to their officers. To them, Rodzianko was totally unacceptable as prime minister and Prince Lvov, less unpopular, became the leader of the new cabinet. In the first Provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

Miliukov became Minister of Foreign Affairs, taking over the ministry from deputy minister Anatoly Neratov

Anatoly Anatolyevich Neratov (Russian: –Р–љ–∞—В–Њ–ї–Є–є –Р–љ–∞—В–Њ–ї—М–µ–≤–Є—З –Э–µ—А–∞—В–Њ–≤) (2 October 1863 in Russia вАУ 10 April 1938 in Villejuif, France) was a Russian diplomat and an official of the Russian foreign ministry.–Р—А—Е–Є–≤ – ...

who had held the office temporarily.

Miliukov sent the British an official request for revolutionary Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( вАУ 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, –Ы–µ–≤ –Ф–∞–≤–Є–і–Њ–≤–Є—З –Ґ—А–Њ—Ж—М–Ї–Є–є; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

to be released from Amherst Internment Camp

Amherst Internment Camp was an internment camp that existed from 1914 to 1919 in Amherst, Nova Scotia. It was the largest internment camp camp in Canada during World War I; a maximum of 853 prisoners were housed at one time at the old Malleable I ...

in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, after the British had boarded a steamer in Halifax harbour to arrest Trotsky and other "dangerous socialists" who were en route to Russia from New York. Upon receiving Milykov's request the British freed Trotsky, who then continued his journey to Russia and became a key planner and leader of the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

that overthrew the provisional government.

He staunchly opposed popular demands for peace at any cost and firmly clung to Russia's wartime alliances. As the Britannica 2004 put it, "he was too inflexible to succeed in practical politics". On 20 April 1917, the government sent a note to Britain and France (which became known as the Miliukov note) proclaiming that Russia would fulfill its obligation towards the Allies and wage the war as long as it was necessary. On the same day, "thousands of armed workers and soldiers came out to demonstrate on the street of Petrograd. Many of them carried banners with slogans calling for the removal of the "ten bourgeois ministers', for an end to the war and for the appointment of a new revolutionary government. The next day the Miliukov Note was condemned by the ministers. This resolved the immediate crisis. On 29 April, the minister of war Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–∞ћБ–љ–і—А –Ш–≤–∞ћБ–љ–Њ–≤–Є—З –У—Г—З–Ї–ЊћБ–≤) (14 October 1862 вАУ 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

...

resigned, and Milyukov's resignation followed on 2 or 4 May. Milyukov was offered a post as Secretary of Education, but refused; he stayed on as the Kadet leader and began to flirt with counter-revolutionary ideas.

Kornilov Affair

In the mass discontent following theJuly Days

The July Days (russian: –Ш—О–ї—М—Б–Ї–Є–µ –і–љ–Є) were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between . It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisi ...

, mainly about Ukrainian autonomy, the Russian populace grew highly skeptical of the Provisional Government's abilities to alleviate the economic distress and social resentment among the lower classes; the word 'provisional' did not command respect. The crowd tired of war and hunger demanded a "peace without annexations or contributions". Milyukov described the situation in Russia in late July as, "Chaos in the army, chaos in foreign policy, chaos in industry and chaos in the nationalist questions". Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov (russian: –Ы–∞–≤—А –У–µ–ЊћБ—А–≥–Є–µ–≤–Є—З –Ъ–Њ—А–љ–ЄћБ–ї–Њ–≤, ; вАУ 13 April 1918) was a Russian military intelligence officer, explorer, and general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and the ensuing Rus ...

, appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian army in July 1917, considered the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: –Я–µ—В—А–Њ–≥—А–∞–і—Б–Ї–Є–є —Б–Њ–≤–µ—В —А–∞–±–Њ—З–Є—Е –Є —Б–Њ–ї–і–∞—В—Б–Ї–Є—Е –і–µ–њ—Г—В–∞—В–Њ–≤, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

responsible for the breakdown in the military in recent times, and believed that the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, –Т—А–µ–Љ–µ–љ–љ–Њ–µ –њ—А–∞–≤–Є—В–µ–ї—М—Б—В–≤–Њ –†–Њ—Б—Б–Є–Є, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

lacked the power and confidence to dissolve the Petrograd Soviet. Following several ambiguous correspondences between Kornilov and Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( вАУ 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Novem ...

, Kornilov commanded an assault on the Petrograd Soviet.

Because the Petrograd Soviet was able to quickly gather a powerful army of workers and soldiers in defense of the Revolution, Kornilov's coup was an abysmal failure and he was placed under arrest. The Kornilov Affair resulted in significantly increased distrust among Russians towards the Provisional Government.

Exile

On 26 October 1917, the party's newspapers were shut down by the new Soviet Government.

On 25 November 1917 Milyukov was elected in the

On 26 October 1917, the party's newspapers were shut down by the new Soviet Government.

On 25 November 1917 Milyukov was elected in the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (–Т—Б–µ—А–Њ—Б—Б–Є–є—Б–Ї–Њ–µ –£—З—А–µ–і–Є—В–µ–ї—М–љ–Њ–µ —Б–Њ–±—А–∞–љ–Є–µ, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

, the first truly free election in Russian history. On 28 November the party was banned by the Soviets and went underground. Milyukov moved from Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, –°–∞–љ–Ї—В-–Я–µ—В–µ—А–±—Г—А–≥, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ЋИsankt p ≤…™t ≤…™rЋИburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914вАУ1924) and later Leningrad (1924вАУ1991), i ...

to the Don Host Oblast

The Province (Oblast) of the Don Cossack Host (, ''OblastвАЩ Voyska Donskogo'') of Imperial Russia was the official name of the territory of Don Cossacks, coinciding approximately with the present-day Rostov Oblast of Russia. Its site of admini ...

. There he became a member of the Don civil council. He advised Mikhail Alekseyev

Mikhail Vasilyevich Alekseyev (russian: –Ь–Є—Е–∞–Є–ї –Т–∞—Б–Є–ї—М–µ–≤–Є—З –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–µ–µ–≤) ( – ) was an Imperial Russian Army general during World War I and the Russian Civil War. Between 1915 and 1917 he served as Tsar Nicholas II's Chi ...

of the Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army (russian: –Ф–Њ–±—А–Њ–≤–Њ–ї—М—З–µ—Б–Ї–∞—П –∞—А–Љ–Є—П, translit=Dobrovolcheskaya armiya, abbreviated to russian: –Ф–Њ–±—А–∞—А–Љ–Є—П, translit=Dobrarmiya) was a White Army active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from ...

. Milyukov and Struve defended a Great Russia

Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' (russian: –Т–µ–ї–Є–Ї–∞—П –†—Г—Б—М, , , , , ), is a name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of Muscovy and later Russia. This was the land to which the et ...

as firmly as the most reactionary monarchist. In May 1918 he went to Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, where he negotiated with the German high command to act together against the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: –С–Њ–ї—М—И–µ–≤–Є–Ї–ЄћБ, from –±–Њ–ї—М—И–Є–љ—Б—В–≤–ЊћБ ''bol'shinstv√≥'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstv√≥'' (–±–Њ–ї—М—И–Є–љ—Б—В–≤–ЊћБ), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. For many members of the Cadet Party, this went too far: Milyukov was forced to resign the presidency of the KDP Central Committee.

Milyukov went to Turkey and from there to Western Europe, to get support from the allies of the White movement, involved in the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. In April 1921 he immigrated to France, where he remained active in politics and edited the Russian-language newspaper ''Poslednie novosti'' (''Latest News)'' (1920вАУ1940). In June 1921 he left the Constitutional Democrats, following a division in the party. Miliukov had called on exiles to abandon hopes in counterrevolution at home, and instead to place their hopes in the peasantry to rise up against the hated Bolshevik regime. The debate between Milyukov and Vasily Maklakov

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov (Russian: –Т–∞—Б–ЄћБ–ї–Є–є –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–µћБ–µ–≤–Є—З –Ь–∞–Ї–ї–∞–Ї–ЊћБ–≤; , Moscow вАУ July 15, 1957, Baden, Switzerland) was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and one ...

began with Maklakov's criticism of the Constitutional Democratic Party. Could the revolutions of 1917 have been prevented if the Kadets had adopted a less radical stance, particularly in 1905-1906? During a performance of the Berliner Philharmonie

The Berliner Philharmonie () is a concert hall in Berlin, Germany, and home to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Philharmonie lies on the south edge of the city's Tiergarten and just west of the former Berlin Wall. The Philharmonie is o ...

on 28 March 1922, his friend Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, the father of the novelist Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, –Т–ї–∞–і–Є–Љ–Є—А –Т–ї–∞–і–Є–Љ–Є—А–Њ–≤–Є—З –Э–∞–±–Њ–Ї–Њ–≤ ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

, was killed while shielding Milyukov from attackers. In 1934, Milyukov was a witness at the Berne Trial

The Berne Trial (also known under the name of "Zionistenprozess") was a famous court case in Berne, Switzerland which took place between 1933 and 1935. Two organisations, the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities () and the Bernese Jewish Commu ...

.

Although he remained an opponent of the communist regime, Milyukov supported Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; вАУ 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's "imperial" foreign policy. On the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, –Ч–ЄћБ–Љ–љ—П—П –≤–Њ–є–љ–∞ћБ, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names SovietвАУFinnish War 1939вАУ1940 (russian: link=no, –°–Њ–≤–µћБ—В—Б–Ї–Њ-—Д–Є–љ—Б–Ї–∞—П –≤–Њ–є–љ–∞ћБ 1939вАУ1940) and SovietвАУFinland War 1 ...

he commented as follows: "I feel pity for the Finns, but I am for the Vyborg guberniya". Already in 1933 he had stated in Prague that, in case of a war between Germany and the USSR, "the emigration must be unconditionally on the side of the Homeland". He supported the Soviet Union in its war effort against Nazi Germany and refused all Nazi rapprochements. He sincerely rejoiced at the Soviet victory in Stalingrad.

Milyukov died in 1943, in Aix-les-Bains

Aix-les-Bains (, ; frp, √Иx-los-Bens; la, Aquae Gratianae), locally simply Aix, is a commune in the southeastern French department of Savoie.

, France. Sometime between 1945 and 1954 his body was reburied at Batignolles Cemetery

The Batignolles Cemetery (french: Cimetière des Batignolles) is a cemetery in Paris.

History

Batignolles Cemetery opened on 22 August 1833. Part of the cemetery had to be closed and the graves moved because of the construction of the great ring ...

, in the ''carré russe-orthodoxe'' (Russian Orthodox section), division 25, next to his wife, Anna Sergeievna.

Works

* *Russia and its crisis (1905)

by P.N. Miliukov

Constitutional government for Russia

an address delivered before the Civic forum by P.N. Miliukov. New York city, 14 January 1908 (1908) * "Past and present of Russian economics" in ''Russian realities & problems: Lectures delivered at Cambridge in August 1916'', by Pavel Milyukov, Peter Struve, Harold Williams, Alexander Lappo-Danilevsky and

Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanis≈Вaw Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 вАУ 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

, Cambridge, University press, 1917, 229p.

Bolshevism: an international danger

by P.N. Miliukov. 1920. * History of the Second Russian Revolution (1921) by P. Milykov.

Russia, to-day and to-morrow (1922)

by P.N. Miliukov.

Notes

References

Further reading

* Aldanov, M. "Professor Milyukov on the Russian Revolution." ''Slavonic Review'' 6#16 (1927), pp. 223вАУ227online

* Breuillard, Sabine. "Russian LiberalismвАФUtopia or Realism? The Individual and the Citizen in the Political Thought of Milyukov." in Robert B Mcklean, ed. ''New Perspectives in Modern Russian History'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1992) pp. 99вАУ116. * Elkin, B. I. "Paul Milyukov (1859вАУ1943)" ''Slavonic and East European Review'' 23#2 (1945), pp. 137вАУ14

online obituary

* Jansen, Dinah. "After October: Russian Liberalism as a 'Work in Progress,' 1919-1945," Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada (2015). * Pearson, Raymond. "Milyukov and the Sixth Kadet Congress." ''Slavonic and East European Review'' 53.131 (1975): 210вАУ229

online

* Riha, Thomas. ''A Russian European: Paul Miliukov in Russian Politics'', (U of Notre Dame Press, 1969), , 373pp. * Stockdale, Melissa Kirschke. ''Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia, 1880вАУ1918'', (Cornell University Press, 1996), , 379pp. * Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." ''Slavonic & East European Review'' 93.2 (2015): 315вАУ337

online

* Zeman, ZbynƒЫk A. ''A diplomatic history of the First World War.'' (1971) pp 207вАУ42.

Other languages

* Thomas M. Bohn: Russische Geschichtswissenschaft von 1880 bis 1905. Pavel N. Miljukov und die Moskauer Schule. B√ґhlau, K√ґln u. a. 1998, * –С–Њ–љ, –Ґ.–Ь. –†—Г—Б—Б–Ї–∞—П –Є—Б—В–Њ—А–Є—З–µ—Б–Ї–∞—П –љ–∞—Г–Ї–∞ /1880 –≥. вАУ 1905 –≥./. –Я–∞–≤–µ–ї –Э–Є–Ї–Њ–ї–∞–µ–≤–Є—З –Ь–Є–ї—О–Ї–Њ–≤ –Є –Ь–Њ—Б–Ї–Њ–≤—Б–Ї–∞—П —И–Ї–Њ–ї–∞. –°.-–Я–µ—В–µ—А–±—Г—А–≥ 2005. * –Ь–∞–Ї—Г—И–Є–љ –Р. –Т., –Ґ—А–Є–±—Г–љ—Б–Ї–Є–є –Я. –Р. –Я–∞–≤–µ–ї –Э–Є–Ї–Њ–ї–∞–µ–≤–Є—З –Ь–Є–ї—О–Ї–Њ–≤: —В—А—Г–і—Л –Є –і–љ–Є (1859вАУ1904). вАФ –†—П–Ј–∞–љ—М, 2001. вАФ 439 —Б. вАФ (–Э–Њ–≤–µ–є—И–∞—П —А–Њ—Б—Б–Є–є—Б–Ї–∞—П –Є—Б—В–Њ—А–Є—П. –Ш—Б—Б–ї–µ–і–Њ–≤–∞–љ–Є—П –Є –і–Њ–Ї—Г–Љ–µ–љ—В—Л. –Ґ–Њ–Љ 1.). вАФExternal links

an early critique of Miliukov's liberalism by

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( вАУ 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, –Ы–µ–≤ –Ф–∞–≤–Є–і–Њ–≤–Є—З –Ґ—А–Њ—Ж—М–Ї–Є–є; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Milyukov, Pavel

1859 births

1943 deaths

Politicians from Moscow

People from Moskovsky Uyezd

Russian Constitutional Democratic Party members

Foreign ministers of Russia

Ministers of the Russian Provisional Government

Members of the 3rd State Duma of the Russian Empire

Members of the 4th State Duma of the Russian Empire

Russian Constituent Assembly members

Historians from the Russian Empire

Male writers from the Russian Empire

Imperial Moscow University alumni

Professorships at the Imperial Moscow University

Sofia University faculty

Members of the Macedonian Scientific Institute

Inmates of Kresty Prison

Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Bulgaria

White Russian emigrants to France

Burials at Batignolles Cemetery

Ogoniok editors