Pavel Florensky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

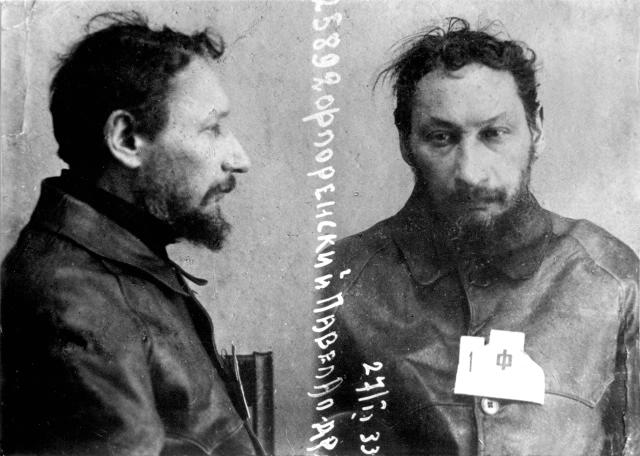

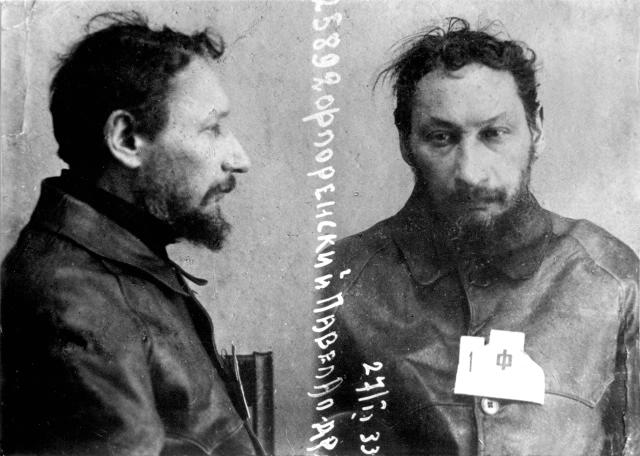

Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky (also P. A. Florenskiĭ, Florenskii, Florenskij; russian: Па́вел Алекса́ндрович Флоре́нский; hy, Պավել Ֆլորենսկի, Pavel Florenski; – December 8, 1937) was a Russian Orthodox

According to the forward in a book of his letters published by the

According to the forward in a book of his letters published by the

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

, polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and neomartyr

The title of New Martyr or Neomartyr ( el, νεο-, ''neo''-, the prefix for "new"; and μάρτυς, ''martys'', "witness") is conferred in some denominations of Christianity to distinguish more recent martyrs and confessors from the old martyr ...

.

Biography

Early life

Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky was born on in the town ofYevlakh

Yevlakh ( az, Yevlax, ) is a city in Azerbaijan, 265 km west of capital Baku. It is surrounded by, but administratively separate from, the Yevlakh District.

Etymology

The settlement is mentioned by the 13th century Armenian historian Step ...

in Elisabethpol Governorate (in present-day western Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

) into the family of a railroad engineer, Aleksandr Florensky. His father came from a family of Russian Orthodox

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: Русское православие) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

priests while his mother Olga (Salomia) Saparova (Saparyan, Sapharashvili) was of the Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

Armenian nobility in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

.Natalino Valentini, (ed.) Pavel Florenskij, ''La colonna e il fondamento della verità'', San Paolo editore, 2010, p. lxxi. His maternal grandmother Sofia Paatova (Paatashvili) was from an Armenian family from Karabakh, living in Bolnisi, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Florensky "always searched for the roots of his Armenian family" and noted that they came from Karabakh

Karabakh ( az, Qarabağ ; hy, Ղարաբաղ, Ġarabaġ ) is a geographic region in present-day southwestern Azerbaijan and eastern Armenia, extending from the highlands of the Lesser Caucasus down to the lowlands between the rivers Kura and ...

.

Florensky completed his high school studies (1893-1899) at the Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

classical lyceum

Liceo classico or Ginnasio (literally ''classical lyceum'') is the oldest, public secondary school type in Italy. Its educational curriculum spans over five years, when students are generally about 14 to 19 years of age.

Until 1969, this was ...

, where several companions were later to distinguish themselves, among them the founder of Russian Cubo-Futurism

Cubo-Futurism (also called Russian Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm) was an art movement that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo ...

, David Burliuk. In 1899, Florensky underwent a religious crisis, connected to a visit to Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

caused by an awareness of the limits and relativity of the scientific positivism and rationality which had been an integral part of his initial formation within his family and high school. He decided to construct his own solution by developing theories that would reconcile the spiritual and the scientific visions on the basis of mathematics. He entered the department of mathematics of the Imperial Moscow University

Imperial Moscow University was one of the oldest universities of the Russian Empire, established in 1755. It was the first of the twelve imperial universities of the Russian Empire.

History of the University

Ivan Shuvalov and Mikhail Lomono ...

and studied under Nikolai Bugaev, and became friends with his son, the future poet and theorist of Russian symbolism

Russian symbolism was an intellectual and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It arose separately from European symbolism, emphasizing mysticism and ostranenie.

Literature

Influences

Primary ...

, Andrei Bely

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev ( rus, Бори́с Никола́евич Буга́ев, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ bʊˈɡajɪf, a=Boris Nikolayevich Bugayev.ru.vorb.oga), better known by the pen name Andrei Bely or Biely ( rus, Андр� ...

. He was particularly drawn to Georg Cantor

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor ( , ; – January 6, 1918) was a German mathematician. He played a pivotal role in the creation of set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance o ...

's set theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies sets, which can be informally described as collections of objects. Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory, as a branch of mathematics, is mostly concern ...

.

He also took courses on ancient philosophy. During this period the young Florensky, who had no religious upbringing, began taking an interest in studies beyond "the limitations of physical knowledge" In 1904 he graduated from the Imperial Moscow University and declined a teaching position at the university: instead, he proceeded to study theology at the Ecclesiastical Academy in Sergiyev Posad

Sergiyev Posad ( rus, Се́ргиев Поса́д, p=ˈsʲɛrgʲɪ(j)ɪf pɐˈsat) is a city and the administrative center of Sergiyevo-Posadsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia. Population:

It was previously known as ''Sergiyev Posad'' (un ...

. During his theological studies there, he came into contact with Elder Isidore on a visit to Gethsemane Hermitage, and Isidore was to become his spiritual guide and father. Together with fellow students Ern, Svenitsky and Brikhnichev he founded a society, the Christian Struggle Union (Союз Христиaнской Борьбы), with the revolutionary aim of rebuilding Russian society according to the principles of Vladimir Solovyov. Subsequently he was arrested for membership in this society in 1906: however, he later lost his interest in the Radical Christianity movement.

Intellectual interests

During his studies at the Ecclesiastical Academy, Florensky's interests includedphilosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

, religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

, art and folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

. He became a prominent member of the Russian Symbolism

Russian symbolism was an intellectual and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It arose separately from European symbolism, emphasizing mysticism and ostranenie.

Literature

Influences

Primary ...

movement, together with his friend Andrei Bely and published works in the magazines ''New Way'' (Новый Путь) and ''Libra'' (Весы). He also started his main philosophical work, ''The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters''. The complete book was published only in 1914 but most of it was finished at the time of his graduation from the academy in 1908.

According to the forward in a book of his letters published by the

According to the forward in a book of his letters published by the Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial ...

: "The book is a series of twelve letters to a 'brother' or 'friend,' who may be understood symbolically as Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

. Central to Florensky's work is an exploration of the various meanings of Christian love, which is viewed as a combination of ''philia'' (friendship) and ''agape'' (universal love). He describes the ancient Christian rites of the '' adelphopoiesis'' (brother-making), which joins male friends in chaste bonds of love. In addition, Florensky was one of the first thinkers in the twentieth century to develop the idea of the Divine Sophia, who has become one of the central concerns of feminist theologians."

Recent research by Michael Hagemeister, known mostly for his work on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, has authenticated that antisemitic material, written under a pseudonym, is in Florensky's hand. Florensky's biographer Avril Pyman evaluates Florensky's position regarding Jews as, contextually for the period, a middle way between liberal critics who excoriated at the time of the incident Russia's backwardness and the behaviour of instigators of pogroms like the Black Hundreds.

After graduating from the academy, he married Anna Giatsintova, the sister of a friend, in August 1910, a move which shocked his friends who were familiar with his aversion to marriage. He continued to teach philosophy and lived at Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra until 1919. In 1911 he was ordained into the priesthood. In 1914 he wrote his dissertation, ''About Spiritual Truth''. He published works on philosophy, theology, art theory, mathematics and electrodynamics

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions o ...

. Between 1911 and 1917 he was the chief editor of the most authoritative Orthodox theological publication of that time, ''Bogoslovskiy Vestnik''. He was also a spiritual teacher of the controversial Russian writer Vasily Rozanov, urging him to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

Period of Communist rule in Russia

After theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

he formulated his position as: "I have developed my own philosophical and scientific worldview, which, though it contradicts the vulgar interpretation of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

... does not prevent me from honestly working in the service of the state." After the Bolsheviks closed the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra (1918) and the Sergievo-Posad Church (1921), where he was the priest, he moved to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

to work on the State Plan for Electrification of Russia (ГОЭЛРО) under the recommendation of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

who strongly believed in Florensky's ability to help the government in the electrification of rural Russia. According to contemporaries, Florensky in his priest's cassock, working alongside other leaders of a Government department, was a remarkable sight.

In 1924, he published a large monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

on dielectric

In electromagnetism, a dielectric (or dielectric medium) is an electrical insulator that can be polarised by an applied electric field. When a dielectric material is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the ma ...

s. He worked simultaneously as the Scientific Secretary of the ''Historical Commission on Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra'' and published his works on ancient Russian art. He was rumoured to be the main organizer of a secret endeavour to save the relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

s of St. Sergii Radonezhsky whose destruction had been ordered by the government.

In the second half of the 1920s, he mostly worked on physics and electrodynamics, eventually publishing his paper '' Imaginary numbers in Geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

'' ( «Мнимости в геометрии. Расширение области двухмерных образов геометрии») devoted to the geometrical interpretation of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in ...

. Among other things, he proclaimed that the geometry of imaginary numbers predicted by the theory of relativity for a body moving faster than light is the geometry of the Kingdom of God. For mentioning the Kingdom of God in that work, he was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda by Soviet authorities.

1928–1937: exile, imprisonment, death

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət ), colloquially shortened to Nizhny, from the 13th to the 17th century Novgorod of the Lower Land, formerly known as Gork ...

. After the intercession of Ekaterina Peshkova (wife of Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

), Florensky was allowed to return to Moscow. On 26 February 1933 he was arrested again, on suspicion of engaging in a conspiracy with Pavel Gidiulianov, a professor of canon law who was a complete stranger to Florensky, to overthrow the state and install, with Nazi assistance, a fascist monarchy. He defended himself vigorously against the imputations until he realized that by showing a willingness to admit them, though false, he would enable several acquaintances to resecure their liberty. He was sentenced to ten years in the labor camps by the infamous Article 58 of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's criminal code (clauses ten and eleven: "agitation against the Soviet system" and "publishing agitation materials against the Soviet system"). The published agitation materials were the monograph about the theory of relativity. His manner of continuing to wear priestly garb annoyed his employers. The state offered him numerous opportunities to go into exile in Paris, but he declined them.

He served at the Baikal Amur Mainline camp until 1934 when he was moved to Solovki, where he conducted research into producing iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , ...

and agar

Agar ( or ), or agar-agar, is a jelly-like substance consisting of polysaccharides obtained from the cell walls of some species of red algae, primarily from ogonori (''Gracilaria'') and "tengusa" (''Gelidiaceae''). As found in nature, agar i ...

out of the local seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of '' Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Phaeophyta'' (brown) and '' Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ...

. In 1937 he was transferred to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(then known as Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

) where, on 25 November, he was sentenced by an extrajudicial

Extrajudicial punishment is a punishment for an alleged crime or offense which is carried out without legal process or supervision by a court or tribunal through a legal proceeding.

Politically motivated

Extrajudicial punishment is often a fe ...

NKVD troika to death. According to a legend he was sentenced for the refusal to disclose the location of the head of St. Sergii Radonezhsky that the communists wanted to destroy. The saint's head was indeed saved and in 1946 the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra was opened again. The relics of St. Sergii became fashionable once more. The saint's relics were returned to Lavra by Pavel Golubtsov, later known as Archbishop Sergiy.

After sentencing, Florensky was transported in a special train together with another 500 prisoners to a location near St. Petersburg, where he was shot dead on the night of 8 December 1937 in a wood not far from the city. The site of his burial is unknown. Antonio Maccioni states that he was shot at the Rzhevsky Artillery Range, near Toksovo

Toksovo (russian: То́ксово; fi, Toksova) is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) in Vsevolozhsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located to the north of St. Petersburg on the Karelian Isthmus. It is served by two neig ...

, which is located about twenty kilometers northeast of Saint Petersburg and was buried in a secret grave in Koirangakangas near Toksovo together with 30,000 others who were executed by the NKVD at the same time. In 1997, a mass burial ditch was excavated in the Sandarmokh

Sandarmokh (russian: Сандармох; krl, Sandarmoh) is a forest massif from Medvezhyegorsk in the Republic of Karelia where possibly thousands of victims of Stalin's Great Terror were executed. More than 58 nationalities were shot and bur ...

forest, which may well contain his remains. His name was registered in 1982 among the list of New Martyrs and Confessor

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death.religious renaissance of his time or scientific thinking, came to be studied in a broader perspective in the 1960s, a change associated with the revival of interest in neglected aspects of his oeuvre shown by the Tartu school of

''ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art''

The Lutterworth Press, 2014 pp.73-94 p.86.

Site devoted to Florensky

The Pavel Florensky School of Theology and Ministry

*

DISF: P.A. Florenskij

- Voice by N. Valentini *

*

Florenskij in Italy - Article by A. Maccioni

*

Page devoted to Florenskij

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Florensky, Pavel 1882 births 1937 deaths 20th-century Christian mystics 20th-century Eastern Orthodox martyrs 20th-century Eastern Orthodox theologians 20th-century Russian philosophers 20th-century Russian scientists Eastern Orthodox mystics Critics of atheism Eastern Orthodox philosophers Eastern Orthodox theologians Executed priests Bamlag detainees Great Purge victims from Azerbaijan Armenian people from the Russian Empire Engineers from the Russian Empire Inventors from the Russian Empire Mathematicians from the Russian Empire Philosophers from the Russian Empire Religious leaders from the Russian Empire Theologians from the Russian Empire Imperial Moscow University alumni People executed by the Soviet Union People from Elizavetpol Governorate People from Yevlakh Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians Russian Christian mystics Russian people of Armenian descent Sophiology Soviet inventors Soviet rehabilitations Soviet theologians

semiotics

Semiotics (also called semiotic studies) is the systematic study of sign processes ( semiosis) and meaning making. Semiosis is any activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, where a sign is defined as anything that communicates something ...

, which evaluated his works in terms of their anticipation of themes that formed part of the theoretical avant-garde's interests in a general theory of cultural signs at that time. Read in this light, the evidence that Florensky's thinking actively responded to the art of the Russian modernists. Of particular importance in this regard was their publication of his 1919 essay, delivered as a lecture the following year, on spatial organization in the Russian icon tradition, entitled " Reverse Perspective", a concept which Florensky, like Erwin Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky (March 30, 1892 in Hannover – March 14, 1968 in Princeton, New Jersey) was a German-Jewish art historian, whose academic career was pursued mostly in the U.S. after the rise of the Nazi regime.

Panofsky's work represents a high ...

later, picked up from Oskar Wulff's 1907 essay, 'Die umgekehrte Perspektive und die Niedersicht. Here Florensky contrasted the dominant concept of spatiality in Renaissance art analysing the visual conventions employed in the iconological tradition. This work has remained since its publication a seminal text in this area down to the present day. In that essay, his interpretation has recently been developed and reformulated critically by Clemena Antonova, who argues rather that what Florensky analysed is better described in terms of "simultaneous planes".Matthew J. Milliner, 'Icons as Theology:The Virgin Mary of Predestination,' in James Romaine, Linda Stratford (eds''ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art''

The Lutterworth Press, 2014 pp.73-94 p.86.

See also

*Vladimir N. Beneshevich

Vladimir Nicolayevich Beneshevich (russian: Влади́мир Никола́евич Бенеше́вич; August 9, 1874 – January 17, 1938) was a Russian scholar of Byzantine history and canon law, and a philologer and paleographer of th ...

*Theophilus of Antioch

:''There is also a Theophilus of Alexandria'' (c. 412 AD).

Theophilus ( el, Θεόφιλος ὁ Ἀντιοχεύς) was Patriarch of Antioch from 169 until 182. He succeeded Eros c. 169, and was succeeded by Maximus I c. 183, according to He ...

*Imiaslavie

''Imiaslavie'' (russian: Имяславие, literally "praising the name") or ''Imiabozhie'' (), also spelled ''imyaslavie'' and ''imyabozhie'', and also referred to as onomatodoxy, is a Christian dogmatic movement that asserts that the name of ...

* Andrei N. Kolmogorov

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

* Superluminal speeds

* Tachyonic particle

* Imaginary mass fields

References

External links

Biographies

Site devoted to Florensky

Works

*The Pavel Florensky School of Theology and Ministry

*

DISF: P.A. Florenskij

- Voice by N. Valentini *

*

Florenskij in Italy - Article by A. Maccioni

*

Page devoted to Florenskij

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Florensky, Pavel 1882 births 1937 deaths 20th-century Christian mystics 20th-century Eastern Orthodox martyrs 20th-century Eastern Orthodox theologians 20th-century Russian philosophers 20th-century Russian scientists Eastern Orthodox mystics Critics of atheism Eastern Orthodox philosophers Eastern Orthodox theologians Executed priests Bamlag detainees Great Purge victims from Azerbaijan Armenian people from the Russian Empire Engineers from the Russian Empire Inventors from the Russian Empire Mathematicians from the Russian Empire Philosophers from the Russian Empire Religious leaders from the Russian Empire Theologians from the Russian Empire Imperial Moscow University alumni People executed by the Soviet Union People from Elizavetpol Governorate People from Yevlakh Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians Russian Christian mystics Russian people of Armenian descent Sophiology Soviet inventors Soviet rehabilitations Soviet theologians