Paul Broca on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician,

Since the 1600s, the majority of medical advancements emerged through interaction in independent and sometimes secret societies.Schiller, 1979, p. 90 The ''Society Anatomique'' ''de Paris'' met every Friday and was chaired by anatomist Jean Cruveilhier, and interned by "the Father of French neurology"

Since the 1600s, the majority of medical advancements emerged through interaction in independent and sometimes secret societies.Schiller, 1979, p. 90 The ''Society Anatomique'' ''de Paris'' met every Friday and was chaired by anatomist Jean Cruveilhier, and interned by "the Father of French neurology"

''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity'' was published the same year as Darwin's presentation of the theory of evolution in the ''On the Origin of Species''. At that time, Broca thought of each racial group as independently created by nature. He was against slavery and disturbed by extinction of native populations caused by colonization. Broca thought that monogenism was often used to justify such actions, when it was argued that, if all races were of a single origin then the lower status of non-Caucasians was caused by how their race acted following creation. He wrote:

''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity'' was published the same year as Darwin's presentation of the theory of evolution in the ''On the Origin of Species''. At that time, Broca thought of each racial group as independently created by nature. He was against slavery and disturbed by extinction of native populations caused by colonization. Broca thought that monogenism was often used to justify such actions, when it was argued that, if all races were of a single origin then the lower status of non-Caucasians was caused by how their race acted following creation. He wrote:

Broca is known for making contributions towards

Broca is known for making contributions towards

Broca is celebrated for his theory that the

Broca is celebrated for his theory that the

"Remarks on the Seat of the Faculty of Articulated Language, Following an Observation of Aphemia (Loss of Speech)"

. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique, Vol. 6, (1861), 330–357. Leborgne died several days later due to an uncontrolled infection and resultant gangrene, Broca performed an autopsy, hoping to find a physical explanation for Leborgne's disability. He determined that, as predicted, Leborgne did in fact have a Broca published his findings from the autopsies of the twelve patients in his paper "Localization of Speech in the Third Left Frontal Cultivation" in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, had made similar observations a generation earlier. Based on his work with approximately forty patients and subjects from other papers, Dax presented his findings at an 1836 conference of southern France physicians in Montpellier. Dax died soon after this presentation and it was not reported or published until after Broca made his initial findings.Finger, 2000, pp. 145–47 Accordingly, Dax's and Broca's conclusions that the left frontal lobe is essential for producing language are considered to be independent.

However, the brains of Leborgne and Lelong had been preserved whole; Broca had never sliced them to reveal the other damaged structures beneath. Over 100 years later Nina Dronkers, an American cognitive neuroscientist, obtained permission to re-examine these brains using modern MRI technology. This imaging resulted in virtual slices of the historic brains and revealed that theses patients had sustained much more damage to the brain than Broca could have known from just studying the outer surface. Their lesions extended to deeper layers beyond the left frontal lobe, including portions of

Broca published his findings from the autopsies of the twelve patients in his paper "Localization of Speech in the Third Left Frontal Cultivation" in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, had made similar observations a generation earlier. Based on his work with approximately forty patients and subjects from other papers, Dax presented his findings at an 1836 conference of southern France physicians in Montpellier. Dax died soon after this presentation and it was not reported or published until after Broca made his initial findings.Finger, 2000, pp. 145–47 Accordingly, Dax's and Broca's conclusions that the left frontal lobe is essential for producing language are considered to be independent.

However, the brains of Leborgne and Lelong had been preserved whole; Broca had never sliced them to reveal the other damaged structures beneath. Over 100 years later Nina Dronkers, an American cognitive neuroscientist, obtained permission to re-examine these brains using modern MRI technology. This imaging resulted in virtual slices of the historic brains and revealed that theses patients had sustained much more damage to the brain than Broca could have known from just studying the outer surface. Their lesions extended to deeper layers beyond the left frontal lobe, including portions of

The discovery of Broca's area revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically

The discovery of Broca's area revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically

''De la propagation de l'inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs dites cancéreuses.''

Doctoral dissertation. * 1856

''Des anévrysmes et de leur traitement.''

Paris: Labé & Asselin * 1861. "Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales". ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 2: 190–204. * 1861. "Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 2: 235–38. * 1861. "Remarques sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé, suivies d'une observation d'aphémie (perte de la parole)." ''Bulletin de la Société Anatomique de Paris'' 6: 330–357 * 1861. "Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales." ''Bulletin de la Société Anatomique'' 36: 398–407. * 1863. "Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du langage articulé." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 4: 200–208. * 1864

''On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo.''

London: Pub. for the Anthropological society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts * 1865

"Sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé."

''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 6: 377–393 * 1866. "Sur la faculté générale du langage, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du langage articulé." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' deuxième série 1: 377–82 * 1871–1878. ''Mémoires d'anthropologie'', 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald

vol. 1

vol. 2

vol. 3

* 1879

"Instructions relatives à l'étude anthropologique du système dentaire."

In: ''Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris'', III° Série. Tome 2, 1879. pp. 128–163.

BibNum

'

anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

and anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms an ...

. He is best known for his research on Broca's area

Broca's area, or the Broca area (, also , ), is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Language processing has been linked to Broca's area since Pier ...

, a region of the frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove be ...

that is named after him. Broca's area is involved with language. His work revealed that the brains of patients with aphasia

Aphasia is an inability to comprehend or formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions. The major causes are stroke and head trauma; prevalence is hard to determine but aphasia due to stroke is estimated to be 0.1–0.4% in ...

contained lesions

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classifi ...

in a particular part of the cortex, in the left frontal region. This was the first anatomical proof of localization of brain function. Broca's work also contributed to the development of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

, advancing the science of anthropometry

Anthropometry () refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthropology and in various atte ...

.

Biography

Paul Broca was born on 28 June 1824 in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande,Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, France, the son of Jean Pierre "Benjamin" Broca, a medical practitioner and former surgeon in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's service, and Annette Thomas, a well-educated daughter of a Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

, Reformed Protestant, preacher. Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

Broca received basic education in the school in his hometown, earning a bachelor's degree at the age of 16. He entered medical school in Paris when he was 17, and graduated at 20, when most of his contemporaries were just beginning as medical students.

After graduating, Broca undertook an extensive internship, first with the urologist

Urology (from Greek οὖρον ''ouron'' "urine" and '' -logia'' "study of"), also known as genitourinary surgery, is the branch of medicine that focuses on surgical and medical diseases of the urinary-tract system and the reproductive org ...

and dermatologist Philippe Ricord (1800–1889) at the Hôpital du Midi, then in 1844 with the psychiatrist François Leuret (1797–1851) at the Bicêtre Hospital. In 1845, he became an intern with Pierre Nicolas Gerdy (1797–1856), a great anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

and surgeon. After two years with Gerdy, Broca became his assistant. In 1848, Broca became the Prosector, performing dissections for lectures of anatomy, at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

Medical School. In 1849, he was awarded a medical doctorate. In 1853, Broca became professor agrégé, and was appointed surgeon of the hospital. He was elected to the chair of external pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

at the Faculty of Medicine in 1867, and one year later professor of clinical surgery. In 1868, he was elected a member of the Académie de medicine, and appointed the Chair of clinical surgery. He served in this capacity until his death. He also worked for the Hôpital St. Antoine, the Pitié, the Hôtel des Clinques, and the Hôpital Necker.

As a researcher, Broca joined the ''Society Anatomique'' ''de Paris'' in 1847. During his first six years in the society, Broca was its most productive contributor.Schiller, 1979, pp. 91, 93. Two months after joining, he was on the society's journal editorial committee. He became its secretary and then vice president by 1851. Soon after its creation in 1848, Broca joined the ''Société de Biologie.'' He also joined and in 1865 became the president of the ''Societe de Chirurgie (Surgery).''

In parallel with his medical career, in 1848, Broca founded a society of free-thinkers, sympathetic to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's theories. He once remarked, "I would rather be a transformed ape than a degenerate son of Adam".Sagan, Carl. 1979. Broca's Brain. Random House: New York . This brought him into conflict with the church, which regarded him as a subversive, materialist, and a corrupter of the youth. The church's animosity toward him continued throughout his lifetime, resulting in numerous confrontations between Broca and the ecclesiastical authorities.

In 1857, feeling pressured by others, and especially his mother, Broca married Adele Augustine Lugol. She came from a Protestant family and was the daughter of a prominent physician Jean Guillaume Auguste Lugol

Jean Guillaume Auguste Lugol (18 August 1786 – 16 September 1851) was a French physician.

Lugol was born in Montauban. He studied medicine in Paris and graduated MD in 1812. In 1819 he was appointed acting physician at the Hôpital Saint-Louis ...

. The Brocas had three children: a daughter Jeanne Francoise Pauline (1858–1935), a son Benjamin Auguste (1859–1924), and a son Élie André (1863–1925). One year later, Broca's mother died and his father, Benjamin, came to Paris to live with the family until his death in 1877.

In 1858, Paul Broca was elected as member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. In 1859, he founded the Society of Anthropology of Paris

The Society of Anthropology of Paris (french: Société d’Anthropologie de Paris) is a French learned society for anthropology founded by Paul Broca in 1859. Broca served as the Secrétaire-général of SAP, and in that capacity responded to a ...

. In 1872, he founded the journal Revue d'anthropologie, and in 1876, the Institute of Anthropology. The French Church opposed the development of anthropology, and in 1876 organized a campaign to stop the teaching of the subject in the Anthropological Institute. In 1872, Broca was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Near the end of his life, Paul Broca was elected a senator for life

A senator for life is a member of the senate or equivalent upper chamber of a legislature who has life tenure. , six Italian senators out of 206, two out of the 41 Burundian senators, one Congolese senator out of 109, and all members of the B ...

, a permanent position in the French senate. He was also a member of the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

and held honorary degrees from many learned institutions, both in France and abroad. He died of a brain hemorrhage on 9 July 1880, at the age of 56. During his life he was an atheist and identified as a Liberal. His wife died in 1914 when she was 79. Like their father, Auguste and Andre went on to study medicine. Auguste Broca became a professor of pediatric surgery, now known for his contribution to the Broca-Perthes-Blankart operation, while André became a professor of medical optics and is known for developing the Pellin-Broca prism.

Early work

Since the 1600s, the majority of medical advancements emerged through interaction in independent and sometimes secret societies.Schiller, 1979, p. 90 The ''Society Anatomique'' ''de Paris'' met every Friday and was chaired by anatomist Jean Cruveilhier, and interned by "the Father of French neurology"

Since the 1600s, the majority of medical advancements emerged through interaction in independent and sometimes secret societies.Schiller, 1979, p. 90 The ''Society Anatomique'' ''de Paris'' met every Friday and was chaired by anatomist Jean Cruveilhier, and interned by "the Father of French neurology" Jean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot (; 29 November 1825 – 16 August 1893) was a French neurologist and professor of anatomical pathology. He worked on hypnosis and hysteria, in particular with his hysteria patient Louise Augustine Gleizes. Charcot is know ...

; both of whom were instrumental in the later discovery of multiple sclerosis

Multiple (cerebral) sclerosis (MS), also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata or disseminated sclerosis, is the most common demyelinating disease, in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This ...

. At its meetings, members would make presentations regarding their scientific findings, which would then be published in the regular bulletin of the society's activities.

Like Cruveilhier and Charcot, Broca made regular ''Society Anatomique'' presentations on musculoskeletal disorder

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are injuries or pain in the human musculoskeletal system, including the joints, ligaments, muscles, nerves, tendons, and structures that support limbs, neck and back. MSDs can arise from a sudden exertion (e.g ...

s. He demonstrated that rickets

Rickets is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children, and is caused by either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stunted growth, bone pain, large forehead, and trouble sleeping. Complications ma ...

, a disorder that results in weak or soft bones in children, was caused by an interference with ossification

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in ...

due to disruption of nutrition., p. 93. In their work on osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of degenerative joint disease that results from breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone which affects 1 in 7 adults in the United States. It is believed to be the fourth leading cause of disability in the ...

, a form of arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

, Broca and Amédée Deville, Broca showed that, like nails and teeth, cartilage is a tissue that requires absorption of nutrients from nearby blood vessels, and described in detail, the process that lead to degeneration of cartilage in joints. Broca also made regular presentations on the clubfoot disorder, a birth defect where infants feet where rotated inwards at birth. At the time Broca saw degeneration of muscle tissue as an explanation for this condition, and while the root cause of it is still undetermined, Broca's theory of the muscle degeneration would lead to understanding the pathology of muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophies (MD) are a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of rare neuromuscular diseases that cause progressive weakness and breakdown of skeletal muscles over time. The disorders differ as to which muscles are primarily af ...

. As an anatomist, Broca can be considered as making 250 separate contributions to medical science.

As a surgeon, Broca wrote a detailed review on recently discovered use of chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with formula C H Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to PTFE. It is also a precursor to various ...

as anesthesia

Anesthesia is a state of controlled, temporary loss of sensation or awareness that is induced for medical or veterinary purposes. It may include some or all of analgesia (relief from or prevention of pain), paralysis (muscle relaxation), ...

, as well as on his own experiences of using novel pain managing methods during surgery, such as hypnosis

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychologica ...

and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

as a local anesthetics. Broca used hypnosis during surgical removal of an abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pressed. The area of redness often extends ...

and received mixed results, as the patient felt pain at the beginning which then went away, and she could not remember anything afterwards. Because, of inconsistent results reported by other doctors, Broca did not repeat in using hypnosis as an anesthetic. Because of his patient's memory loss, he saw the most potential in using it as a psychological tool. In 1856, Broca published ''On Aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus ( ...

s and their Treatment,'' a detailed, almost a thousand page long review of all accessible records on diagnosis and surgical and non treatment for these weakened blood vessels conditions. This book was one of the first published monograms on a specific subject. Before his later achievements, it was this work, that Broca was known for by other French doctors.

In 1857, Broca contributed to Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard's work on the nervous system, conducting vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

experiments, where specific spinal nerves were cut to demonstrate the spinal pathways for sensory and motor systems. As a result of this work. Brown-Séquard became known for demonstrating the principle of decussation, where a vertebrate's neural fibers cross from one lateral side to another, resulting in phenomenon of the right side of that animals brain controlling the left side of the other.Schiller, 1979, pp. 102–103

As a scientist, Broca also developed theories and made hypotheses that would eventually be disproven. Based on reported findings, for example, he published work in support of viewing syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

as a virus. When western medicine discovered the qualities of the muscle relaxant curare

Curare ( /kʊˈrɑːri/ or /kjʊˈrɑːri/; ''koo-rah-ree'' or ''kyoo-rah-ree'') is a common name for various alkaloid arrow poisons originating from plant extracts. Used as a paralyzing agent by indigenous peoples in Central and South ...

, used by South American Indian hunters as poison, Broca thought there was strong support for the incorrect idea that, aside from being applied topically, curare could also be diluted and ingested to counter tetanus caused muscle spasms.

Broca also spent many of his earlier years researching cancer. His wife had a known family history of carcinoma, and it is possible that this piqued his interest in exploring possible hereditary causes of cancer. In his investigations, he accumulated evidence supporting the hereditary nature of some cancers while also discovering that cancer cells can run through the blood. Many scientists were skeptical of Broca's hereditary hypothesis, with most believing that it is merely coincidental. He stated two hypotheses for the cause of cancer, diathesis and infection. He believed that the cause may lie somewhere between the two. He then hypothesized that (1) diathesis produces the first cancer (2) cancer produces infection, and (3) infection produces secondary multiple tumors, cachexia, and death."

Anthropology

Broca spent much time at his Anthropological Institute studying skulls and bones. It has been argued that he was attempting to use the measurements obtained by these studies as his main criteria for ranking racial groups in order of superiority. In that sense, Broca was a pioneer in the study of physical anthropology a part of which has been called 'scientific racism.' He advanced the science of cranial anthropometry by developing many new types of measuring instruments ( craniometers) and numerical indices. He published around 223 papers on general anthropology, physical anthropology, ethnology, and other branches of this field. He founded the '' Société d'Anthropologie de Paris'' in 1859, the ''Revue d'Anthropologie'' in 1872, and the School of Anthropology in Paris in 1876. Broca first became acquainted with anthropology through the works of Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Antoine Étienne Reynaud Augustin Serres and Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, and by the late 1850s it became his lifetime interest. Broca defined Anthropology as "the study of the human group, considered as whole." Like other scientists, he rejected relying on religious texts, and looked for a scientific explanation of human origins. In 1857, Broca was presented with a hybrid leporid, a result of a cross species reproduction between a rabbit and hare. The crossbreeding was done for commercial rather than scientific reasons, as the resulting hybrids became very popular pets. Specific circumstances had to be set up in order for differently behaving species to reproduce and for their hybrid descendants to be able to reproduce between themselves. To Broca, the fact that different animals are able to intermix and create fertile offspring did not prove that they were of the same species. In 1858, Broca presented these findings on leporids to the ''Société de Biologie.'' He believed that the key element of his work was its implication that physical differences between human races could be explained by them being different species with different origins rather than the single moment of creation. While Charles Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' did not come out until the following year, the topic of human origin was already widely discussed in science, but still capable of producing a negative response from the government. Because of that worry, Pierre Rayer the president of the Société, along with other members with which Broca was on good relations, asked Broca to stop further discussion of the topic. Broca agreed, but was adamant for the discussion to continue, so in 1859 he formed the Société d'Anthropologie.

Racial groups and human species

As a proponent ofpolygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

, Broca rejected the monogenistic approach that all humans have a common ancestor. Instead he viewed human racial groups as coming from different origins. Like most of the proponents on either side, he viewed each racial group as having a place on a 'barbarism' to 'civilization' progression. He saw European colonization of other territories as justified by its being an attempt to civilize the barbaric populations. In his 1859 work ''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity in the Genus Homo'', he argued that it was reasonable to view humanity as composed of independent racial groups – such as Australian, Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian

Ethiopians are the native inhabitants of Ethiopia, as well as the global diaspora of Ethiopia. Ethiopians constitute several component ethnic groups, many of which are closely related to ethnic groups in neighboring Eritrea and other parts of ...

, and American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

. He saw each racial group as its own species, connected to a geographic location. All together, these different species were part of the single genus homo. Per the standard of the time, Broca would also refer to the Caucasian racial group as white, and to the Ethiopian racial group as Negro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

. In his writings, Broca's use of the word ''race'' was narrower than how it is used today. Broca considered Celts, Gauls, Greeks, Persians and Arabs to be distinct races that were part of the Caucasian racial group. Races within each group had specific physical characteristics that distinguished them from other racial groups. Like his work in anatomy, Broca emphasized that his conclusions rested on empirical evidence, rather than ''a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ex ...

'' reasoning. He thought that the distinct geographic location of each racial group was one of the main problems with the monogenists argument for common ancestry: Broca also felt that there was not enough evidence for the theory that appearance of different races could be changed by the qualities of the environments that they lived in. Broca saw the physical characteristic of Jews being the same as those portrayed in the Egyptian paintings from the 2,500 b.c., even though, by 1850 A.D. that population had spread to different locations with vastly different environments. He pointed out that his opponents were unable to provide similar long-term comparisons.

Hybridity

Broca, influenced by previous work ofSamuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer who argued against the single creation story of the Bible, monogenism, instead supporting a theory of multiple racial creations, poly ...

, used the concept of hybridity Hybridity, in its most basic sense, refers to mixture. The term originates from biology and was subsequently employed in linguistics and in racial theory in the nineteenth century. Young, Robert. ''Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and R ...

as his primary argument against monogenism, and that it was flawed to see all of humanity as a single species. Different racial groups' ability to reproduce with each was not sufficient to prove that idea. Under Broca's view on hybridity, the result of a reproduction between two different races could fall into four categories: 1) The resulting offspring are infertile; 2) Where the resulting offspring are infertile when they reproduce between themselves but are sometimes successful when they reproduce with the parent groups; 3) Known as paragenesic, where the offspring's descendants are able reproduce within themselves and with parents, but the success of the reproduction lowers with every generation until it ends; and 4) Known as eugenesic, where a successful reproduction can continue indefinitely, between the intermix descendants and with the parent group.

Looking at historical population figures, Broca concluded that the population of France was an example of a eugenesic mixed race, resulting from intermixing of Cimri, Celtic, Germanic and Northern races within the Caucasian group. On the other hand, the thought that observations and population data from different regions of Africa, Southeast Asia, and North and South America, showed a significant decrease in physical and intellectual abilities of mixed groups when compared to the different races that they originated from. Concluding that intermixed descendants of different racial groups could only be Paragenesic. ''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity'' was published the same year as Darwin's presentation of the theory of evolution in the ''On the Origin of Species''. At that time, Broca thought of each racial group as independently created by nature. He was against slavery and disturbed by extinction of native populations caused by colonization. Broca thought that monogenism was often used to justify such actions, when it was argued that, if all races were of a single origin then the lower status of non-Caucasians was caused by how their race acted following creation. He wrote:

''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity'' was published the same year as Darwin's presentation of the theory of evolution in the ''On the Origin of Species''. At that time, Broca thought of each racial group as independently created by nature. He was against slavery and disturbed by extinction of native populations caused by colonization. Broca thought that monogenism was often used to justify such actions, when it was argued that, if all races were of a single origin then the lower status of non-Caucasians was caused by how their race acted following creation. He wrote:

Craniometry

Broca is known for making contributions towards

Broca is known for making contributions towards anthropometry

Anthropometry () refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthropology and in various atte ...

—the scientific approach to measurements of human physical features. He developed numerous instruments and data points that were the basis of current methods of medical and archeological craniometry. Specifically, cranial points like glabella

The glabella, in humans, is the area of skin between the eyebrows and above the nose. The term also refers to the underlying bone that is slightly depressed, and joins the two brow ridges. It is a cephalometric landmark that is just superior t ...

and inion and instruments like craniograph and stereograph. Unlike Morton, who believed that a subject's brain size was the main indicator of intelligence, Broca thought that there were other factors that were more important. These included prognathic

Prognathism, also called Habsburg jaw or Habsburgs' jaw primarily in the context of its prevalence amongst members of the House of Habsburg, is a positional relationship of the mandible or maxilla to the skeletal base where either of the jaws pr ...

facial angles, with closer to right angles indicating higher intelligence, and the cephalic index relationship between the brain's length and width, that was directly proportional with intelligence, with the most intelligent European group being 'long headed', while the least intelligent Negro group being 'short headed'.Ashok, 2017, p. 32 He thought that the most important aspect, was the relative size between the frontal and rear areas of the brain, with Caucasians having a larger frontal area than Negroes. Broca eventually came to the conclusion that larger skulls were not associated with higher intelligence, but still believed brain size was important in some aspects such as social progress, material security, and education. He compared cranial capacity of different types of Parisian skulls. In doing so he found that the average oldest Parisian skull was smaller than a modern, wealthier Parisian skull and that both were bigger than the average skull from a poor Parisian's grave. Aside from his approaches to craniometry, Broca made other contributions to anthropometry, such as developing field work scales and measuring techniques for classifying eye, skin, and hair color, designed to resist water and sunlight damage.

Criticism

Darwin

In 1868 the English naturalistCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

criticized Broca for believing in the existence of a tailless mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It ...

of the Ceylon junglefowl

The Sri Lankan junglefowl (''Gallus lafayettii'' sometimes spelled ''Gallus lafayetii''), also known as the Ceylon junglefowl or Lafayette's junglefowl, is a member of the Galliformes bird order which is endemic to Sri Lanka, where it is the nati ...

, described in 1807 by the Dutch aristocrat

The aristocracy is historically associated with "hereditary" or "ruling" social class. In many states, the aristocracy included the upper class of people (aristocrats) with hereditary rank and titles. In some, such as ancient Greece, ancient R ...

, zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and d ...

and museum director Coenraad Jacob Temminck

Coenraad Jacob Temminck (; 31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist and museum director.

Biography

Coenraad Jacob Temminck was born on 31 March 1778 in Amsterdam in the Dutch Republic. From his father, Jacob Temmi ...

.

Stephen Jay Gould

Broca was one of the first anthropologists engaged incomparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in ...

of primates and humans. Comparing then dominant craniometry-based measures of intelligence as well as other factors such as relative forearm-to-arm length, he proposed that Negroes were an intermediate form between apes and Europeans. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Goul ...

criticized Broca and his contemporaries of being engaged in "scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

" when conducting their research. Basing their work on biological determinism, and "''a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ex ...

'' expectations" that "social and economic differences between human groups—primarily races, classes, and sexes—arise from inherited, inborn distinctions and that society, in this sense, is an accurate reflection of biology."

Evolution

Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species'' was published in 1859, and two years later Broca published ''On the Phenomenon of Hybridity.'' Soon after Darwin's publication, Broca accepted evolution as one of the main elements of a broader explanation for diversification of species: "I am one of those who do not think that Charles Darwin has discovered the true agents of organic evolution; on the other hand I am not one of those who fail to recognize the greatness of his work ... Vital competition ... is a law; the resultant selection is a fact; individual variation, another fact." He came to reject polygenism as applied to humans, conceding that all races were of single origin. In 1866, after the discovery of a chinless and protruded neanderthal jaw, he wrote: "I have already had occasion to state that I am not a Darwinist ... Yet I do not hesitate ... to call this the first link in the chain which, according to the Darwinists, extends from man to ape..." He saw some differences between groups of animals as too distinct to be explained through evolution from a single source:Even on a narrower level Broca saw evolution as insufficient explanation for the presence of some traits:Ultimately, Broca believed that there had to be a process that ran parallel to evolution, to fully explain the origins of, and divergences, between different species.Language

Broca's area

Broca is celebrated for his theory that the

Broca is celebrated for his theory that the speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

production center of the brain is located on the left side of the brain and for pinpointing the location to the ventroposterior region of the frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove be ...

s (now known as Broca's area

Broca's area, or the Broca area (, also , ), is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Language processing has been linked to Broca's area since Pier ...

). He arrived at this discovery by studying the brains of aphasic

Aphasia is an inability to comprehend or formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions. The major causes are stroke and head trauma; prevalence is hard to determine but aphasia due to stroke is estimated to be 0.1–0.4% in t ...

patients (persons with speech and language disorders resulting from brain injuries).Fancher, Raymond E. ''Pioneers of Psychology'', 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990 (1979), pp. 72–93

This area of study began for Broca with the dispute between the proponents of cerebral localization – whose views derived from the phrenology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

of Franz Joseph Gall

Franz Josef Gall (; 9 March 175822 August 1828) was a German neuroanatomist, physiologist, and pioneer in the study of the localization of mental functions in the brain.

Claimed as the founder of the pseudoscience of phrenology, Gall was an ...

– and their opponents led by Pierre Flourens

Marie Jean Pierre Flourens (13 April 1794 – 6 December 1867), father of Gustave Flourens, was a French physiologist, the founder of experimental brain science, and a pioneer in anesthesia.

Biography

Flourens was born at Maureilhan, near Bézie ...

. Phrenologists believed that the human mind has a set of various mental faculties, each one represented in a different area of the brain. With specific areas representing personality characteristics like one's aggressiveness or spirituality, but also memory and linguistic abilities. Their opponents claimed that, by careful ablation

Ablation ( la, ablatio – removal) is removal or destruction of something from an object by vaporization, chipping, erosive processes or by other means. Examples of ablative materials are described below, and include spacecraft material for ...

(specific way of removing material) of various brain regions, Flourens had disproved Gall's hypotheses. However, Gall's former student, Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud, kept the localization of function hypothesis alive (especially with regards to a "language center"), although he rejected much of the remaining phrenological thinking. In 1848, Bouillaud relied on his work with brain-damaged patients to challenge other professionals to disprove him by finding a case of frontal lobe damage unaccompanied by a disorder of speech. His son-in-law, Ernest Aubertin (1825–1893), began seeking out cases to either support or disprove the theory, and he found several in support of it.

Broca's Society of Anthropology of Paris

The Society of Anthropology of Paris (french: Société d’Anthropologie de Paris) is a French learned society for anthropology founded by Paul Broca in 1859. Broca served as the Secrétaire-général of SAP, and in that capacity responded to a ...

was where language was regularly discussed in the context of race and nationality, it also became a platform for addressing its physiological aspects. The localization of function controversy became a topic of regular debate when several experts of head and brain anatomy, including Aubertin, joined the society. Most of these experts still supported Flourens argument, but Aubertin was persistent in presenting new patients to counter their views. However, it was Broca, not Aubertin, who finally put the localization issue to rest.

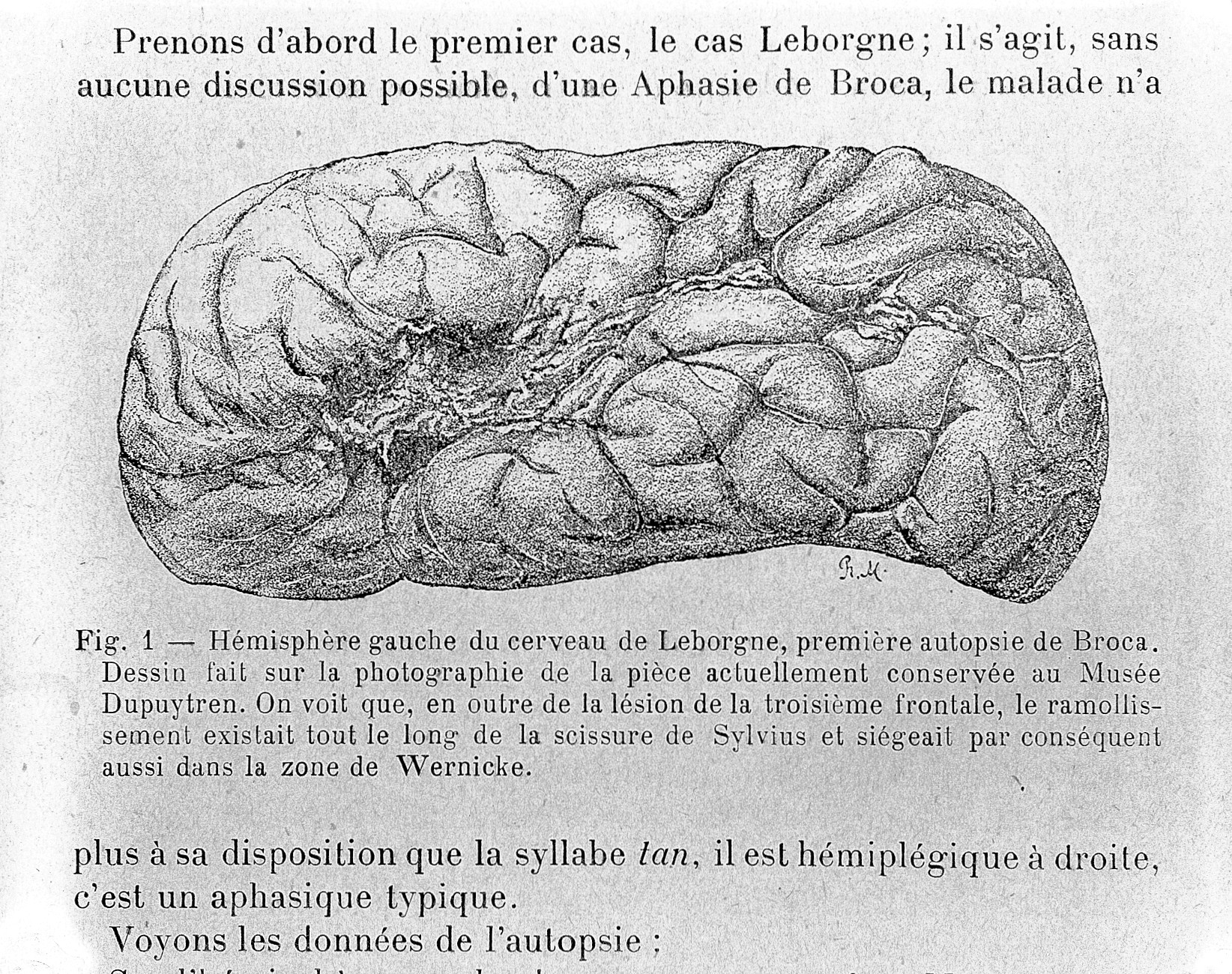

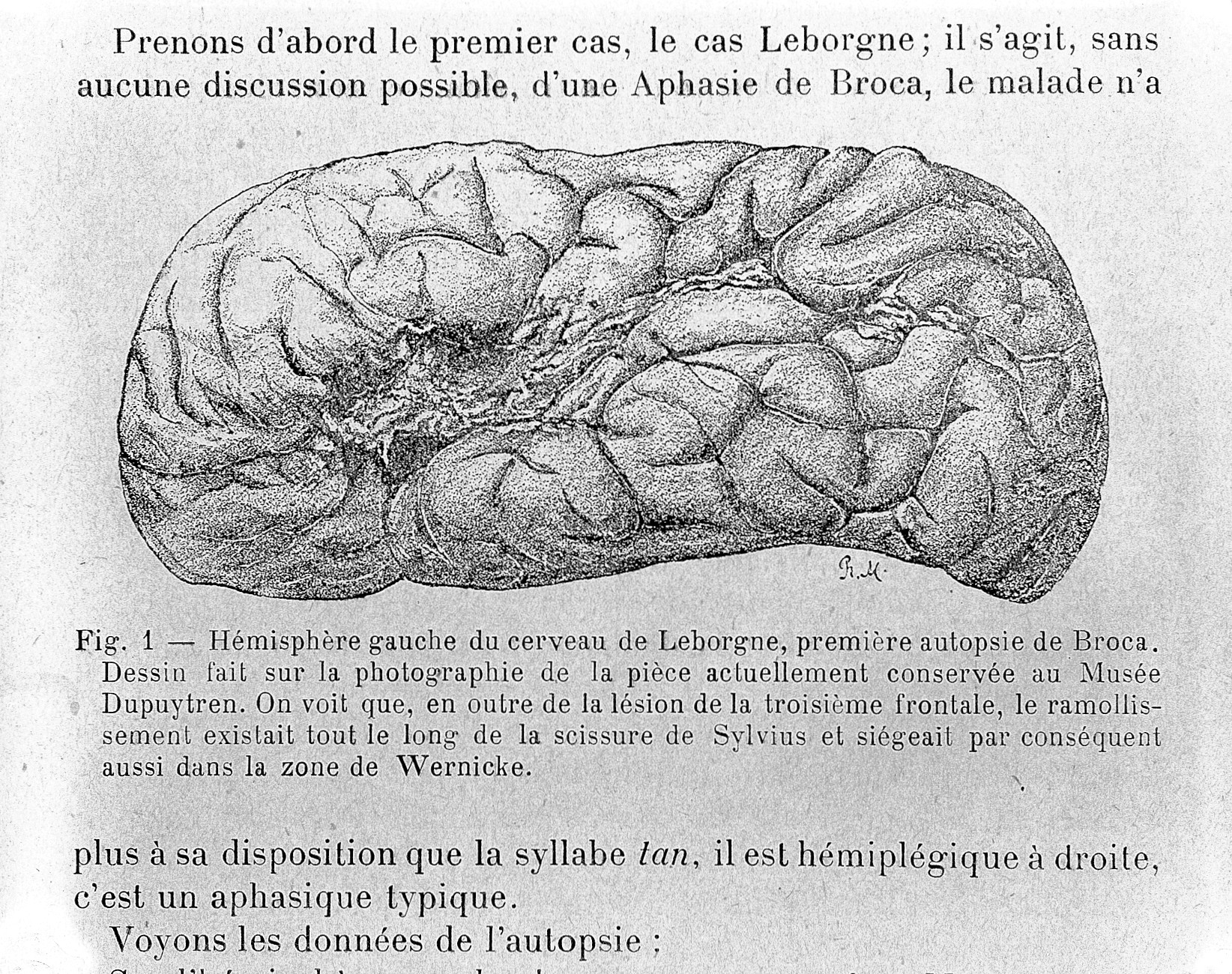

In 1861, Broca visited a patient in the Bicêtre Hospital named Louis Victor Leborgne, who had a 21-year progressive loss of speech and paralysis but not a loss of comprehension nor mental function. He was nicknamed "Tan" due to his inability to clearly speak any words other than "tan" (pronounced \tɑ̃\, as in the French word ''temps'', "time").Broca, Paul"Remarks on the Seat of the Faculty of Articulated Language, Following an Observation of Aphemia (Loss of Speech)"

. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique, Vol. 6, (1861), 330–357. Leborgne died several days later due to an uncontrolled infection and resultant gangrene, Broca performed an autopsy, hoping to find a physical explanation for Leborgne's disability. He determined that, as predicted, Leborgne did in fact have a

lesion

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classif ...

in the frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove be ...

in one of the cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum ( brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemisphere ...

s, which in this case turned out to be the left. From a comparative progression of Leborgne's loss of speech and motor movement, the area of the brain important for speech production was determined to lie within the third convolution of the left frontal lobe, next to the lateral sulcus. One day after Tan's death Broca presented his findings to the anthropological society.

A second case after Leborgne is what solidified Broca's beliefs that human speech function was localized. Lazare Lelong was an 84-year-old grounds worker who was being treated at Bicêtre for dementia. He had also lost the ability to speak other than five simple, meaningful words – these included his own name, "yes", "no", "always" as well as the number "three". After his death his brain was also autopsied. Broca found a lesion that encompassed much the same area as had been affected in Leborgne's brain. This finding concluded that a specific area controlled one's ability to produce meaningful sounds, and when it is affected, one can lose their capability to communicate. For the next two years, Broca went on to find autopsy evidence from twelve more cases in support of the localization of articulated language.

Broca published his findings from the autopsies of the twelve patients in his paper "Localization of Speech in the Third Left Frontal Cultivation" in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, had made similar observations a generation earlier. Based on his work with approximately forty patients and subjects from other papers, Dax presented his findings at an 1836 conference of southern France physicians in Montpellier. Dax died soon after this presentation and it was not reported or published until after Broca made his initial findings.Finger, 2000, pp. 145–47 Accordingly, Dax's and Broca's conclusions that the left frontal lobe is essential for producing language are considered to be independent.

However, the brains of Leborgne and Lelong had been preserved whole; Broca had never sliced them to reveal the other damaged structures beneath. Over 100 years later Nina Dronkers, an American cognitive neuroscientist, obtained permission to re-examine these brains using modern MRI technology. This imaging resulted in virtual slices of the historic brains and revealed that theses patients had sustained much more damage to the brain than Broca could have known from just studying the outer surface. Their lesions extended to deeper layers beyond the left frontal lobe, including portions of

Broca published his findings from the autopsies of the twelve patients in his paper "Localization of Speech in the Third Left Frontal Cultivation" in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, had made similar observations a generation earlier. Based on his work with approximately forty patients and subjects from other papers, Dax presented his findings at an 1836 conference of southern France physicians in Montpellier. Dax died soon after this presentation and it was not reported or published until after Broca made his initial findings.Finger, 2000, pp. 145–47 Accordingly, Dax's and Broca's conclusions that the left frontal lobe is essential for producing language are considered to be independent.

However, the brains of Leborgne and Lelong had been preserved whole; Broca had never sliced them to reveal the other damaged structures beneath. Over 100 years later Nina Dronkers, an American cognitive neuroscientist, obtained permission to re-examine these brains using modern MRI technology. This imaging resulted in virtual slices of the historic brains and revealed that theses patients had sustained much more damage to the brain than Broca could have known from just studying the outer surface. Their lesions extended to deeper layers beyond the left frontal lobe, including portions of insular cortex

The insular cortex (also insula and insular lobe) is a portion of the cerebral cortex folded deep within the lateral sulcus (the fissure separating the temporal lobe from the parietal and frontal lobes) within each hemisphere of the mammalian b ...

and critical white matter pathways below the cortex. This work was published in a peer-reviewed article, and has been cited.

The brains of many of Broca's aphasic patients are still preserved and available for viewing on a limited basis in the special collections of the Pierre-and-Marie-Curie University (UPMC) in Paris. The collection was formerly displayed in the Musée Dupuytren

The Musée Dupuytren was a museum of wax anatomical items and specimens illustrating diseases and malformations. It was located at the Cordeliers Convent building, 15, rue de l'Ecole de Médecine, Les Cordeliers, Paris, France, and is part of the ...

. His collection of casts is in the Musée d'Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière. Broca presented his study on Leborgne in 1861 in the ''Bulletin of the Société Anatomique''.

Patients with damage to Broca's area or to neighboring regions of the left inferior frontal lobe are often categorized clinically as having Expressive aphasia

Expressive aphasia, also known as Broca's aphasia, is a type of aphasia characterized by partial loss of the ability to produce language ( spoken, manual, or written), although comprehension generally remains intact. A person with expressive apha ...

(also known as Broca's aphasia). This type of aphasia, which often involves impairments in speech output, can be contrasted with receptive aphasia

Wernicke's aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, sensory aphasia or posterior aphasia, is a type of aphasia in which individuals have difficulty understanding written and spoken language. Patients with Wernicke's aphasia demonstrate fluent ...

, (also known as Wernicke's aphasia), named for Karl Wernicke, which is characterized by damage to more posterior regions of the left temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The temporal lobe is located beneath the lateral fissure on both cerebral hemispheres of the mammalian brain.

The temporal lobe is involved i ...

, and is often characterized by impairments in language comprehension.

Broca's legacy

The discovery of Broca's area revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically

The discovery of Broca's area revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically Wernicke's area

Wernicke's area (; ), also called Wernicke's speech area, is one of the two parts of the cerebral cortex that are linked to speech, the other being Broca's area. It is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language, in contrast to B ...

.

New research has found that dysfunction in the area may lead to other speech disorders such as stuttering

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder in which the flow of speech is disrupted by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses or blocks in which the ...

and apraxia of speech. Recent anatomical neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is the use of quantitative (computational) techniques to study the structure and function of the central nervous system, developed as an objective way of scientifically studying the healthy human brain in a non-invasive manner. Incr ...

studies have shown that the pars opercularis of Broca's area is anatomically smaller in individuals who stutter whereas the pars triangularis

The inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), (gyrus frontalis inferior), is the lowest positioned gyrus of the frontal gyri, of the frontal lobe, and is part of the prefrontal cortex.

Its superior border is the inferior frontal sulcus (which divides it f ...

appears to be normal.

He also invented more than 20 measuring instruments for the use in craniology, and helped standardize measuring procedures.

His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Selected publications

* 1849''De la propagation de l'inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs dites cancéreuses.''

Doctoral dissertation. * 1856

''Des anévrysmes et de leur traitement.''

Paris: Labé & Asselin * 1861. "Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales". ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 2: 190–204. * 1861. "Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 2: 235–38. * 1861. "Remarques sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé, suivies d'une observation d'aphémie (perte de la parole)." ''Bulletin de la Société Anatomique de Paris'' 6: 330–357 * 1861. "Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales." ''Bulletin de la Société Anatomique'' 36: 398–407. * 1863. "Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du langage articulé." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 4: 200–208. * 1864

''On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo.''

London: Pub. for the Anthropological society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts * 1865

"Sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé."

''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' 6: 377–393 * 1866. "Sur la faculté générale du langage, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du langage articulé." ''Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie'' deuxième série 1: 377–82 * 1871–1878. ''Mémoires d'anthropologie'', 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald

vol. 1

vol. 2

vol. 3

* 1879

"Instructions relatives à l'étude anthropologique du système dentaire."

In: ''Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris'', III° Série. Tome 2, 1879. pp. 128–163.

Notes

References

Literature

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * "Paul Broca's discovery of the area of the brain governing articulated language", analysis of Broca's 1861 article, onBibNum

'

lick 'à télécharger' for English version

Lick may refer to:

* Licking, the action of passing the tongue over a surface

Places

* Lick (crater), a crater on the Moon named after James Lick

* 1951 Lick, an asteroid named after James Lick

* Lick Township, Jackson County, Ohio, United Sta ...

/small>.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Broca, Paul Pierre

1824 births

1880 deaths

19th-century French male writers

École pratique des hautes études faculty

French anthropologists

French anatomists

French atheists

French medical writers

French neuroscientists

French life senators

History of neuroscience

Huguenots

Members of the Académie Française

Members of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

People from Gironde

Race and intelligence controversy

Proponents of scientific racism