Oxygen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the

chalcogen

The chalcogens (ore forming) ( ) are the chemical elements in group 16 of the periodic table. This group is also known as the oxygen family. Group 16 consists of the elements oxygen (O), sulfur (S), selenium (Se), tellurium (Te), and the radioac ...

group

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic ide ...

in the periodic table, a highly reactive

Reactive may refer to:

*Generally, capable of having a reaction (disambiguation)

*An adjective abbreviation denoting a bowling ball coverstock made of reactive resin

*Reactivity (chemistry)

*Reactive mind

*Reactive programming

See also

*Reactanc ...

nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as well as with other compounds. Oxygen is Earth's most abundant element, and after hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

and helium, it is the third-most abundant element in the universe. At standard temperature and pressure, two atoms of the element bind

BIND () is a suite of software for interacting with the Domain Name System (DNS). Its most prominent component, named (pronounced ''name-dee'': , short for ''name daemon''), performs both of the main DNS server roles, acting as an authoritative ...

to form dioxygen

There are several known allotropes of oxygen. The most familiar is molecular oxygen (O2), present at significant levels in Earth's atmosphere and also known as dioxygen or triplet oxygen. Another is the highly reactive ozone (O3). Others are:

* ...

, a colorless and odorless diatomic gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

with the formula . Diatomic oxygen gas currently constitutes 20.95% of the Earth's atmosphere, though this has changed considerably over long periods of time. Oxygen makes up almost half of the Earth's crust in the form of oxides.Atkins, P.; Jones, L.; Laverman, L. (2016).''Chemical Principles'', 7th edition. Freeman.

Many major classes of organic molecules in living organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fungi ...

s contain oxygen atoms, such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple est ...

s, as do the major constituent inorganic compounds of animal shells, teeth, and bone. Most of the mass of living organisms is oxygen as a component of water, the major constituent of lifeforms. Oxygen is continuously replenished in Earth's atmosphere by photosynthesis, which uses the energy of sunlight to produce oxygen from water and carbon dioxide. Oxygen is too chemically reactive to remain a free element in air without being continuously replenished by the photosynthetic action of living organisms. Another form ( allotrope) of oxygen, ozone (), strongly absorbs ultraviolet UVB

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

radiation and the high-altitude ozone layer helps protect the biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also ...

from ultraviolet radiation

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

. However, ozone present at the surface is a byproduct of smog and thus a pollutant.

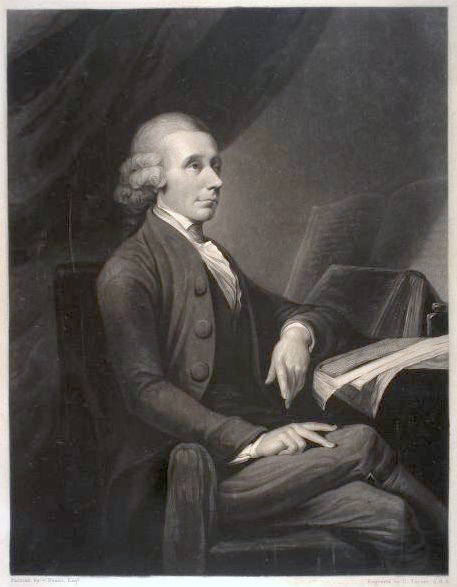

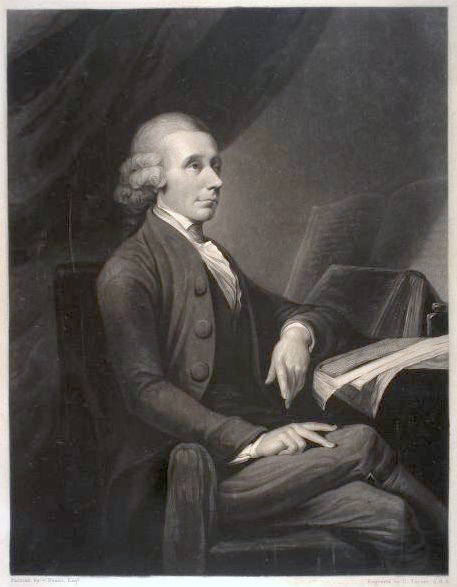

Oxygen was isolated by Michael Sendivogius before 1604, but it is commonly believed that the element was discovered independently by Carl Wilhelm Scheele, in Uppsala, in 1773 or earlier, and Joseph Priestley in Wiltshire, in 1774. Priority is often given for Priestley because his work was published first. Priestley, however, called oxygen "dephlogisticated air", and did not recognize it as a chemical element. The name ''oxygen'' was coined in 1777 by Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

steel, plastics and textiles, brazing, welding and cutting of steels and other metals, rocket propellant, oxygen therapy, and life support systems in aircraft, submarines, spaceflight and diving.

Polish alchemist, philosopher, and physician Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój) in his work ''De Lapide Philosophorum Tractatus duodecim e naturae fonte et manuali experientia depromti'' (1604) described a substance contained in air, referring to it as 'cibus vitae' (food of life,) and according to Polish historian Roman Bugaj, this substance is identical with oxygen. Sendivogius, during his experiments performed between 1598 and 1604, properly recognized that the substance is equivalent to the gaseous byproduct released by the

Polish alchemist, philosopher, and physician Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój) in his work ''De Lapide Philosophorum Tractatus duodecim e naturae fonte et manuali experientia depromti'' (1604) described a substance contained in air, referring to it as 'cibus vitae' (food of life,) and according to Polish historian Roman Bugaj, this substance is identical with oxygen. Sendivogius, during his experiments performed between 1598 and 1604, properly recognized that the substance is equivalent to the gaseous byproduct released by the

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation and gave the first correct explanation of how combustion works. He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book ''Sur la combustion en général'', which was published in 1777. In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and ''azote'' (Gk. ' "lifeless"), which did not support either. ''Azote'' later became ''

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation and gave the first correct explanation of how combustion works. He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book ''Sur la combustion en général'', which was published in 1777. In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and ''azote'' (Gk. ' "lifeless"), which did not support either. ''Azote'' later became ''

John Dalton's original atomic hypothesis presumed that all elements were monatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, leading to the conclusion that the atomic mass of oxygen was 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16. In 1805,

John Dalton's original atomic hypothesis presumed that all elements were monatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, leading to the conclusion that the atomic mass of oxygen was 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16. In 1805,  In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer

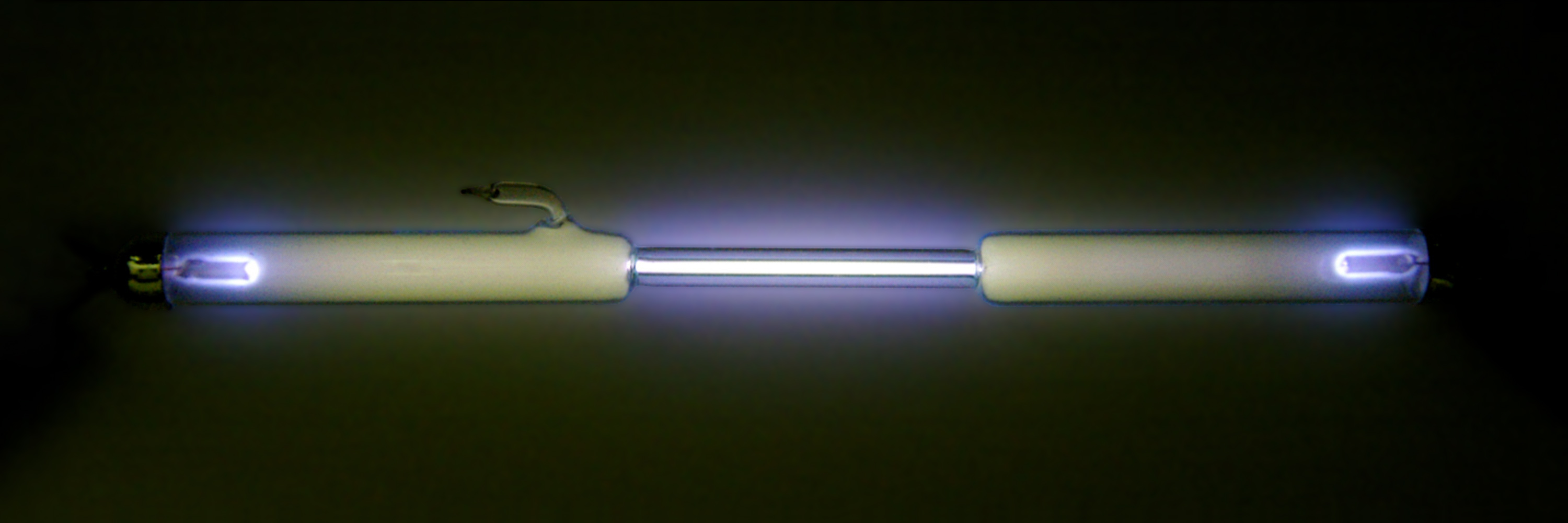

At standard temperature and pressure, oxygen is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas with the

At standard temperature and pressure, oxygen is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas with the

Google Books

accessed January 31, 2015. This combination of cancellations and σ and π overlaps results in dioxygen's double-bond character and reactivity, and a triplet electronic ground state. An electron configuration with two unpaired electrons, as is found in dioxygen orbitals (see the filled π* orbitals in the diagram) that are of equal energy—i.e., In the triplet form, molecules are

In the triplet form, molecules are

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter, and seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter. At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for freshwater and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Both liquid and solid are clear substances with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter, and seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter. At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for freshwater and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Both liquid and solid are clear substances with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to

Naturally occurring oxygen is composed of three stable isotopes, 16O, 17O, and 18O, with 16O being the most abundant (99.762% natural abundance).

Most 16O is synthesized at the end of the

Naturally occurring oxygen is composed of three stable isotopes, 16O, 17O, and 18O, with 16O being the most abundant (99.762% natural abundance).

Most 16O is synthesized at the end of the

The unusually high concentration of oxygen gas on Earth is the result of the

The unusually high concentration of oxygen gas on Earth is the result of the

Paleoclimatologists measure the ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in the shells and skeletons of marine organisms to determine the climate millions of years ago (see

Paleoclimatologists measure the ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in the shells and skeletons of marine organisms to determine the climate millions of years ago (see

In nature, free oxygen is produced by the light-driven splitting of water during oxygenic photosynthesis. According to some estimates, green algae and cyanobacteria in marine environments provide about 70% of the free oxygen produced on Earth, and the rest is produced by terrestrial plants. Other estimates of the oceanic contribution to atmospheric oxygen are higher, while some estimates are lower, suggesting oceans produce ~45% of Earth's atmospheric oxygen each year.

A simplified overall formula for photosynthesis is

: 6 + 6 + photons → + 6

or simply

: carbon dioxide + water + sunlight → glucose + dioxygen

Photolytic oxygen evolution occurs in the

In nature, free oxygen is produced by the light-driven splitting of water during oxygenic photosynthesis. According to some estimates, green algae and cyanobacteria in marine environments provide about 70% of the free oxygen produced on Earth, and the rest is produced by terrestrial plants. Other estimates of the oceanic contribution to atmospheric oxygen are higher, while some estimates are lower, suggesting oceans produce ~45% of Earth's atmospheric oxygen each year.

A simplified overall formula for photosynthesis is

: 6 + 6 + photons → + 6

or simply

: carbon dioxide + water + sunlight → glucose + dioxygen

Photolytic oxygen evolution occurs in the

Free oxygen gas was almost nonexistent in Earth's atmosphere before photosynthetic archaea and

Free oxygen gas was almost nonexistent in Earth's atmosphere before photosynthetic archaea and

One hundred million tonnes of are extracted from air for industrial uses annually by two primary methods. The most common method is fractional distillation of liquefied air, with

One hundred million tonnes of are extracted from air for industrial uses annually by two primary methods. The most common method is fractional distillation of liquefied air, with

Oxygen storage methods include high-pressure oxygen tanks, cryogenics and chemical compounds. For reasons of economy, oxygen is often transported in bulk as a liquid in specially insulated tankers, since one liter of liquefied oxygen is equivalent to 840 liters of gaseous oxygen at atmospheric pressure and . Such tankers are used to refill bulk liquid-oxygen storage containers, which stand outside hospitals and other institutions that need large volumes of pure oxygen gas. Liquid oxygen is passed through

Oxygen storage methods include high-pressure oxygen tanks, cryogenics and chemical compounds. For reasons of economy, oxygen is often transported in bulk as a liquid in specially insulated tankers, since one liter of liquefied oxygen is equivalent to 840 liters of gaseous oxygen at atmospheric pressure and . Such tankers are used to refill bulk liquid-oxygen storage containers, which stand outside hospitals and other institutions that need large volumes of pure oxygen gas. Liquid oxygen is passed through

Uptake of from the air is the essential purpose of

Uptake of from the air is the essential purpose of

An application of as a low-pressure

An application of as a low-pressure

Smelting of iron ore into steel consumes 55% of commercially produced oxygen. In this process, is injected through a high-pressure lance into molten iron, which removes sulfur impurities and excess carbon as the respective oxides, and . The reactions are exothermic, so the temperature increases to 1,700 ° C.

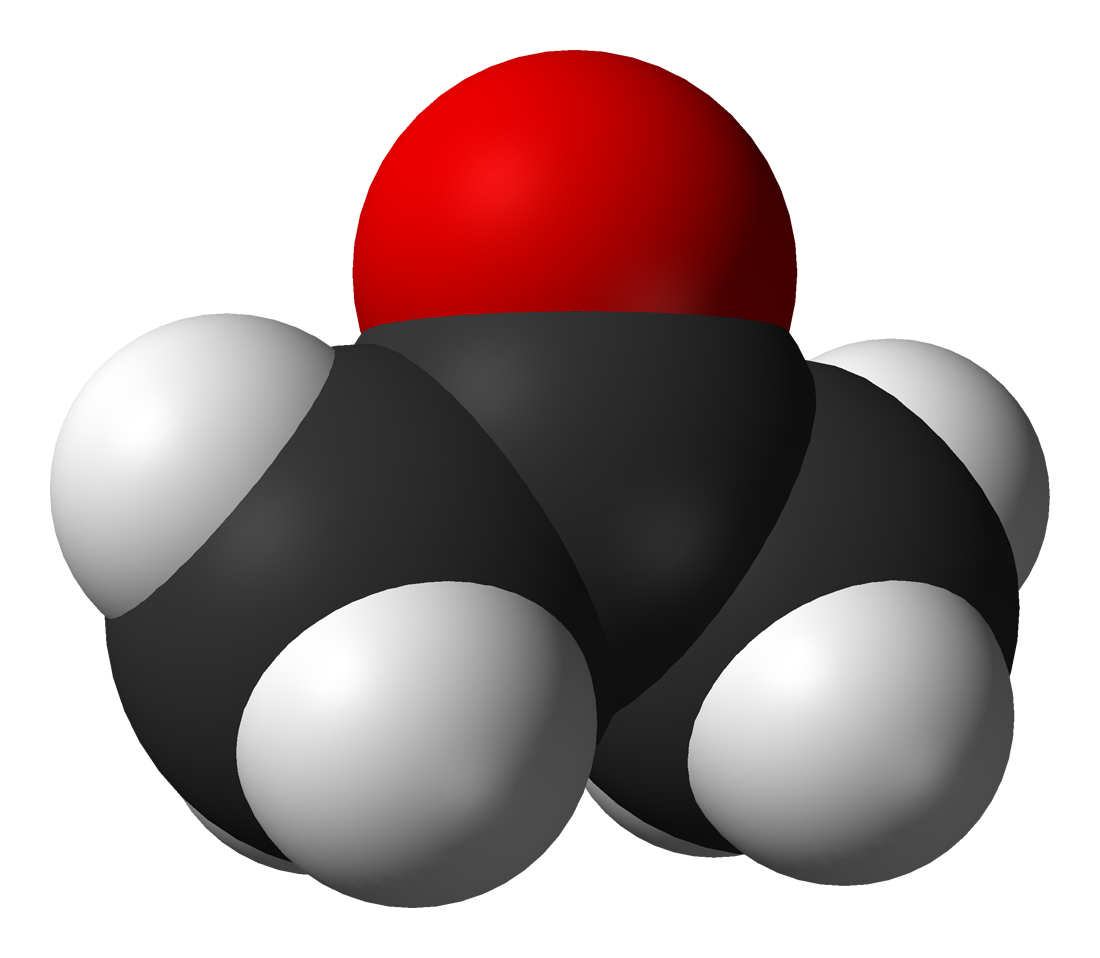

Another 25% of commercially produced oxygen is used by the chemical industry. Ethylene is reacted with to create

Smelting of iron ore into steel consumes 55% of commercially produced oxygen. In this process, is injected through a high-pressure lance into molten iron, which removes sulfur impurities and excess carbon as the respective oxides, and . The reactions are exothermic, so the temperature increases to 1,700 ° C.

Another 25% of commercially produced oxygen is used by the chemical industry. Ethylene is reacted with to create

The oxidation state of oxygen is −2 in almost all known compounds of oxygen. The oxidation state −1 is found in a few compounds such as peroxides. Compounds containing oxygen in other oxidation states are very uncommon: −1/2 (

The oxidation state of oxygen is −2 in almost all known compounds of oxygen. The oxidation state −1 is found in a few compounds such as peroxides. Compounds containing oxygen in other oxidation states are very uncommon: −1/2 (

Due to its

Due to its

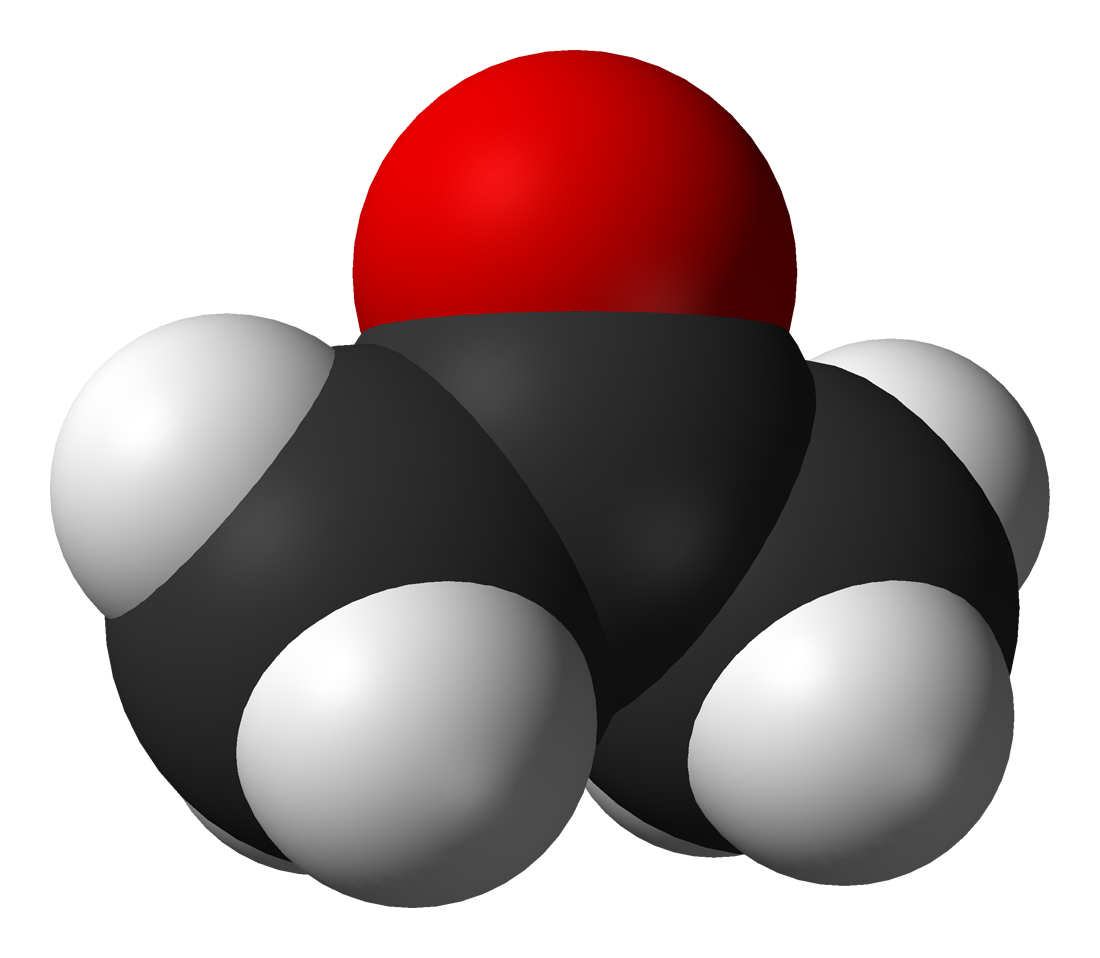

Among the most important classes of organic compounds that contain oxygen are (where "R" is an organic group): alcohols (R-OH); ethers (R-O-R); ketones (R-CO-R); aldehydes (R-CO-H); carboxylic acids (R-COOH); esters (R-COO-R);

Among the most important classes of organic compounds that contain oxygen are (where "R" is an organic group): alcohols (R-OH); ethers (R-O-R); ketones (R-CO-R); aldehydes (R-CO-H); carboxylic acids (R-COOH); esters (R-COO-R);

Oxygen gas () can be toxic at elevated partial pressures, leading to convulsions and other health problems.Since 's partial pressure is the fraction of times the total pressure, elevated partial pressures can occur either from high fraction in breathing gas or from high breathing gas pressure, or a combination of both. Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 511 Oxygen toxicity usually begins to occur at partial pressures more than 50 kilo pascals (kPa), equal to about 50% oxygen composition at standard pressure or 2.5 times the normal sea-level partial pressure of about 21 kPa. This is not a problem except for patients on

Oxygen gas () can be toxic at elevated partial pressures, leading to convulsions and other health problems.Since 's partial pressure is the fraction of times the total pressure, elevated partial pressures can occur either from high fraction in breathing gas or from high breathing gas pressure, or a combination of both. Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 511 Oxygen toxicity usually begins to occur at partial pressures more than 50 kilo pascals (kPa), equal to about 50% oxygen composition at standard pressure or 2.5 times the normal sea-level partial pressure of about 21 kPa. This is not a problem except for patients on

Highly concentrated sources of oxygen promote rapid combustion. Fire and explosion hazards exist when concentrated oxidants and fuels are brought into close proximity; an ignition event, such as heat or a spark, is needed to trigger combustion. Oxygen is the oxidant, not the fuel.

Concentrated will allow combustion to proceed rapidly and energetically. Steel pipes and storage vessels used to store and transmit both gaseous and liquid oxygen will act as a fuel; and therefore the design and manufacture of systems requires special training to ensure that ignition sources are minimized. The fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew in a launch pad test spread so rapidly because the capsule was pressurized with pure but at slightly more than atmospheric pressure, instead of the normal pressure that would be used in a mission.

Liquid oxygen spills, if allowed to soak into organic matter, such as wood, petrochemicals, and asphalt can cause these materials to detonate unpredictably on subsequent mechanical impact.

Highly concentrated sources of oxygen promote rapid combustion. Fire and explosion hazards exist when concentrated oxidants and fuels are brought into close proximity; an ignition event, such as heat or a spark, is needed to trigger combustion. Oxygen is the oxidant, not the fuel.

Concentrated will allow combustion to proceed rapidly and energetically. Steel pipes and storage vessels used to store and transmit both gaseous and liquid oxygen will act as a fuel; and therefore the design and manufacture of systems requires special training to ensure that ignition sources are minimized. The fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew in a launch pad test spread so rapidly because the capsule was pressurized with pure but at slightly more than atmospheric pressure, instead of the normal pressure that would be used in a mission.

Liquid oxygen spills, if allowed to soak into organic matter, such as wood, petrochemicals, and asphalt can cause these materials to detonate unpredictably on subsequent mechanical impact.

Oxygen

at ''

Oxidizing Agents > Oxygen

Roald Hoffmann article on "The Story of O"

*

Scripps Institute: Atmospheric Oxygen has been dropping for 20 years

{{featured article Chemical elements Diatomic nonmetals Reactive nonmetals Chalcogens Chemical substances for emergency medicine Breathing gases E-number additives Oxidizing agents

History of study

Early experiments

One of the first known experiments on the relationship between combustion and air was conducted by the 2nd century BCEGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

writer on mechanics, Philo of Byzantium. In his work ''Pneumatica'', Philo observed that inverting a vessel over a burning candle and surrounding the vessel's neck with water resulted in some water rising into the neck. Philo incorrectly surmised that parts of the air in the vessel were converted into the classical element fire and thus were able to escape through pores in the glass. Many centuries later Leonardo da Vinci built on Philo's work by observing that a portion of air is consumed during combustion and respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

. Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 499.

In the late 17th century, Robert Boyle proved that air is necessary for combustion. English chemist John Mayow (1641–1679) refined this work by showing that fire requires only a part of air that he called ''spiritus nitroaereus''. In one experiment, he found that placing either a mouse or a lit candle in a closed container over water caused the water to rise and replace one-fourteenth of the air's volume before extinguishing the subjects. From this, he surmised that nitroaereus is consumed in both respiration and combustion.

Mayow observed that antimony increased in weight when heated, and inferred that the nitroaereus must have combined with it. He also thought that the lungs separate nitroaereus from air and pass it into the blood and that animal heat and muscle movement result from the reaction of nitroaereus with certain substances in the body. Accounts of these and other experiments and ideas were published in 1668 in his work ''Tractatus duo'' in the tract "De respiratione".

Phlogiston theory

Robert Hooke, Ole Borch, Mikhail Lomonosov, and Pierre Bayen all produced oxygen in experiments in the 17th and the 18th century but none of them recognized it as a chemical element. Emsley 2001, p. 299 This may have been in part due to the prevalence of the philosophy of combustion and corrosion called the ''phlogiston theory'', which was then the favored explanation of those processes. Established in 1667 by the German alchemist J. J. Becher, and modified by the chemistGeorg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl (22 October 1659 – 24 May 1734) was a German chemist, physician and philosopher. He was a supporter of vitalism, and until the late 18th century his works on phlogiston were accepted as an explanation for chemical processes.K ...

by 1731, phlogiston theory stated that all combustible materials were made of two parts. One part, called phlogiston, was given off when the substance containing it was burned, while the dephlogisticated part was thought to be its true form, or calx

Calx is a substance formed from an ore or mineral that has been heated.

Calx, especially of a metal, is now known as an oxide. According to the obsolete phlogiston theory, the calx was the true elemental substance, having lost its phlogiston in t ...

.

Highly combustible materials that leave little residue

Residue may refer to:

Chemistry and biology

* An amino acid, within a peptide chain

* Crop residue, materials left after agricultural processes

* Pesticide residue, refers to the pesticides that may remain on or in food after they are applied ...

, such as wood or coal, were thought to be made mostly of phlogiston; non-combustible substances that corrode, such as iron, contained very little. Air did not play a role in phlogiston theory, nor were any initial quantitative experiments conducted to test the idea; instead, it was based on observations of what happens when something burns, that most common objects appear to become lighter and seem to lose something in the process.

Discovery

Polish alchemist, philosopher, and physician Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój) in his work ''De Lapide Philosophorum Tractatus duodecim e naturae fonte et manuali experientia depromti'' (1604) described a substance contained in air, referring to it as 'cibus vitae' (food of life,) and according to Polish historian Roman Bugaj, this substance is identical with oxygen. Sendivogius, during his experiments performed between 1598 and 1604, properly recognized that the substance is equivalent to the gaseous byproduct released by the

Polish alchemist, philosopher, and physician Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój) in his work ''De Lapide Philosophorum Tractatus duodecim e naturae fonte et manuali experientia depromti'' (1604) described a substance contained in air, referring to it as 'cibus vitae' (food of life,) and according to Polish historian Roman Bugaj, this substance is identical with oxygen. Sendivogius, during his experiments performed between 1598 and 1604, properly recognized that the substance is equivalent to the gaseous byproduct released by the thermal decomposition

Thermal decomposition, or thermolysis, is a chemical decomposition caused by heat. The decomposition temperature of a substance is the temperature at which the substance chemically decomposes. The reaction is usually endothermic as heat is re ...

of potassium nitrate. In Bugaj's view, the isolation of oxygen and the proper association of the substance to that part of air which is required for life, provides sufficient evidence for the discovery of oxygen by Sendivogius. This discovery of Sendivogius was however frequently denied by the generations of scientists and chemists which succeeded him.

It is also commonly claimed that oxygen was first discovered by Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. He had produced oxygen gas by heating mercuric oxide

Mercury(II) oxide, also called mercuric oxide or simply mercury oxide, is the inorganic compound with the formula Hg O. It has a red or orange color. Mercury(II) oxide is a solid at room temperature and pressure. The mineral form montroydite is v ...

(HgO) and various nitrates in 1771–72. Scheele called the gas "fire air" because it was then the only known agent to support combustion. He wrote an account of this discovery in a manuscript titled ''Treatise on Air and Fire'', which he sent to his publisher in 1775. That document was published in 1777. Emsley 2001, p. 300

In the meantime, on August 1, 1774, an experiment conducted by the British clergyman Joseph Priestley focused sunlight on mercuric oxide contained in a glass tube, which liberated a gas he named "dephlogisticated air". Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 500 He noted that candles burned brighter in the gas and that a mouse was more active and lived longer while breathing it. After breathing the gas himself, Priestley wrote: "The feeling of it to my lungs was not sensibly different from that of common air, but I fancied that my breast felt peculiarly light and easy for some time afterwards." Priestley published his findings in 1775 in a paper titled "An Account of Further Discoveries in Air", which was included in the second volume of his book titled '' Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air''. Because he published his findings first, Priestley is usually given priority in the discovery.

The French chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier later claimed to have discovered the new substance independently. Priestley visited Lavoisier in October 1774 and told him about his experiment and how he liberated the new gas. Scheele had also dispatched a letter to Lavoisier on September 30, 1774, which described his discovery of the previously unknown substance, but Lavoisier never acknowledged receiving it. (A copy of the letter was found in Scheele's belongings after his death.)

Lavoisier's contribution

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation and gave the first correct explanation of how combustion works. He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book ''Sur la combustion en général'', which was published in 1777. In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and ''azote'' (Gk. ' "lifeless"), which did not support either. ''Azote'' later became ''

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation and gave the first correct explanation of how combustion works. He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book ''Sur la combustion en général'', which was published in 1777. In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and ''azote'' (Gk. ' "lifeless"), which did not support either. ''Azote'' later became ''nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

'' in English, although it has kept the earlier name in French and several other European languages.

Etymology

Lavoisier renamed 'vital air' to ''oxygène'' in 1777 from theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

roots '' (oxys)'' ( acid, literally "sharp", from the taste of acids) and ''-γενής (-genēs)'' (producer, literally begetter), because he mistakenly believed that oxygen was a constituent of all acids. Chemists (such as Sir Humphry Davy in 1812) eventually determined that Lavoisier was wrong in this regard, but by then the name was too well established.

''Oxygen'' entered the English language despite opposition by English scientists and the fact that the Englishman Priestley had first isolated the gas and written about it. This is partly due to a poem praising the gas titled "Oxygen" in the popular book '' The Botanic Garden'' (1791) by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin.

Later history

John Dalton's original atomic hypothesis presumed that all elements were monatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, leading to the conclusion that the atomic mass of oxygen was 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16. In 1805,

John Dalton's original atomic hypothesis presumed that all elements were monatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, leading to the conclusion that the atomic mass of oxygen was 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16. In 1805, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (, , ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen (with Alexander von Humboldt), for two laws ...

and Alexander von Humboldt showed that water is formed of two volumes of hydrogen and one volume of oxygen; and by 1811 Amedeo Avogadro

Lorenzo Romano Amedeo Carlo Avogadro, Count of Quaregna and Cerreto (, also , ; 9 August 17769 July 1856) was an Italian scientist, most noted for his contribution to molecular theory now known as Avogadro's law, which states that equal volume ...

had arrived at the correct interpretation of water's composition, based on what is now called Avogadro's law and the diatomic elemental molecules in those gases.These results were mostly ignored until 1860. Part of this rejection was due to the belief that atoms of one element would have no chemical affinity In chemical physics and physical chemistry, chemical affinity is the electronic property by which dissimilar chemical species are capable of forming chemical compounds. Chemical affinity can also refer to the tendency of an atom or compound to co ...

towards atoms of the same element, and part was due to apparent exceptions to Avogadro's law that were not explained until later in terms of dissociating molecules.

The first commercial method of producing oxygen was chemical, the so-called Brin process involving a reversible reaction of barium oxide

Barium oxide, also known as baria, is a white hygroscopic non-flammable compound with the formula BaO. It has a cubic structure and is used in cathode ray tubes, crown glass, and catalysts. It is harmful to human skin and if swallowed in larg ...

. It was invented in 1852 and commercialized in 1884, but was displaced by newer methods in early 20th century.

By the late 19th century scientists realized that air could be liquefied and its components isolated by compressing and cooling it. Using a cascade method, Swiss chemist and physicist Raoul Pierre Pictet evaporated

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humi ...

liquid sulfur dioxide in order to liquefy carbon dioxide, which in turn was evaporated to cool oxygen gas enough to liquefy it. He sent a telegram on December 22, 1877, to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris announcing his discovery of liquid oxygen. Just two days later, French physicist Louis Paul Cailletet announced his own method of liquefying molecular oxygen. Only a few drops of the liquid were produced in each case and no meaningful analysis could be conducted. Oxygen was liquefied in a stable state for the first time on March 29, 1883, by Polish scientists from Jagiellonian University, Zygmunt Wróblewski Zygmunt, Zigmunt, Zigmund and spelling variations thereof are masculine given names and occasionally surnames. People so named include:

Given name Medieval period

* Sigismund I the Old (1467–1548), Zygmunt I Stary in Polish, King of Poland and Gr ...

and Karol Olszewski.

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde

Carl Paul Gottfried von Linde (11 June 1842 – 16 November 1934) was a German scientist, engineer, and businessman. He discovered a refrigeration cycle and invented the first industrial-scale air separation and gas liquefaction processes, whi ...

and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them separately. Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene welding was demonstrated for the first time by burning a mixture of acetylene and compressed . This method of welding and cutting metal later became common.

In 1923, the American scientist Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first liquid-fueled rocket. Goddard successfully laun ...

became the first person to develop a rocket engine that burned liquid fuel; the engine used gasoline for fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer. Goddard successfully flew a small liquid-fueled rocket 56 m at 97 km/h on March 16, 1926, in Auburn, Massachusetts, US.

In academic laboratories, oxygen can be prepared by heating together potassium chlorate mixed with a small proportion of manganese dioxide.

Oxygen levels in the atmosphere are trending slightly downward globally, possibly because of fossil-fuel burning.

Characteristics

Properties and molecular structure

molecular formula

In chemistry, a chemical formula is a way of presenting information about the chemical proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound or molecule, using chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, ...

, referred to as dioxygen.

As ''dioxygen'', two oxygen atoms are chemically bound to each other. The bond can be variously described based on level of theory, but is reasonably and simply described as a covalent double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betwee ...

that results from the filling of molecular orbitals formed from the atomic orbitals of the individual oxygen atoms, the filling of which results in a bond order of two. More specifically, the double bond is the result of sequential, low-to-high energy, or Aufbau, filling of orbitals, and the resulting cancellation of contributions from the 2s electrons, after sequential filling of the low σ and σ* orbitals; σ overlap of the two atomic 2p orbitals that lie along the O–O molecular axis and π overlap of two pairs of atomic 2p orbitals perpendicular to the O–O molecular axis, and then cancellation of contributions from the remaining two 2p electrons after their partial filling of the π* orbitals.Jack Barrett, 2002, "Atomic Structure and Periodicity", (Basic concepts in chemistry, Vol. 9 of Tutorial chemistry texts), Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry, p. 153, . SeGoogle Books

accessed January 31, 2015. This combination of cancellations and σ and π overlaps results in dioxygen's double-bond character and reactivity, and a triplet electronic ground state. An electron configuration with two unpaired electrons, as is found in dioxygen orbitals (see the filled π* orbitals in the diagram) that are of equal energy—i.e.,

degenerate

Degeneracy, degenerate, or degeneration may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Degenerate (album), ''Degenerate'' (album), a 2010 album by the British band Trigger the Bloodshed

* Degenerate art, a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party i ...

—is a configuration termed a spin triplet state. Hence, the ground state of the molecule is referred to as triplet oxygen

Triplet oxygen, 3O2, refers to the ''S'' = 1 electronic ground state of molecular oxygen (dioxygen). It is the most stable and common allotrope of oxygen. Molecules of triplet oxygen contain two unpaired electrons, making triplet oxygen an unus ...

.An orbital is a concept from quantum mechanics that models an electron as a wave-like particle that has a spatial distribution about an atom or molecule. The highest-energy, partially filled orbitals are antibonding, and so their filling weakens the bond order from three to two. Because of its unpaired electrons, triplet oxygen reacts only slowly with most organic molecules, which have paired electron spins; this prevents spontaneous combustion.

In the triplet form, molecules are

In the triplet form, molecules are paramagnetic

Paramagnetism is a form of magnetism whereby some materials are weakly attracted by an externally applied magnetic field, and form internal, induced magnetic fields in the direction of the applied magnetic field. In contrast with this behavior, ...

. That is, they impart magnetic character to oxygen when it is in the presence of a magnetic field, because of the spin magnetic moments of the unpaired electrons in the molecule, and the negative exchange energy between neighboring molecules. Liquid oxygen is so magnetic that, in laboratory demonstrations, a bridge of liquid oxygen may be supported against its own weight between the poles of a powerful magnet.

Singlet oxygen is a name given to several higher-energy species of molecular in which all the electron spins are paired. It is much more reactive with common organic molecules than is normal (triplet) molecular oxygen. In nature, singlet oxygen is commonly formed from water during photosynthesis, using the energy of sunlight. It is also produced in the troposphere

The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. From ...

by the photolysis of ozone by light of short wavelength and by the immune system as a source of active oxygen. Carotenoids in photosynthetic organisms (and possibly animals) play a major role in absorbing energy from singlet oxygen and converting it to the unexcited ground state before it can cause harm to tissues.

Allotropes

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen

There are several known allotropes of oxygen. The most familiar is molecular oxygen (O2), present at significant levels in Earth's atmosphere and also known as dioxygen or triplet oxygen. Another is the highly reactive ozone (O3). Others are:

* ...

, , the major part of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen (see Occurrence). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498 kJ/mol. O2 is used by complex forms of life, such as animals, in cellular respiration. Other aspects of are covered in the remainder of this article.

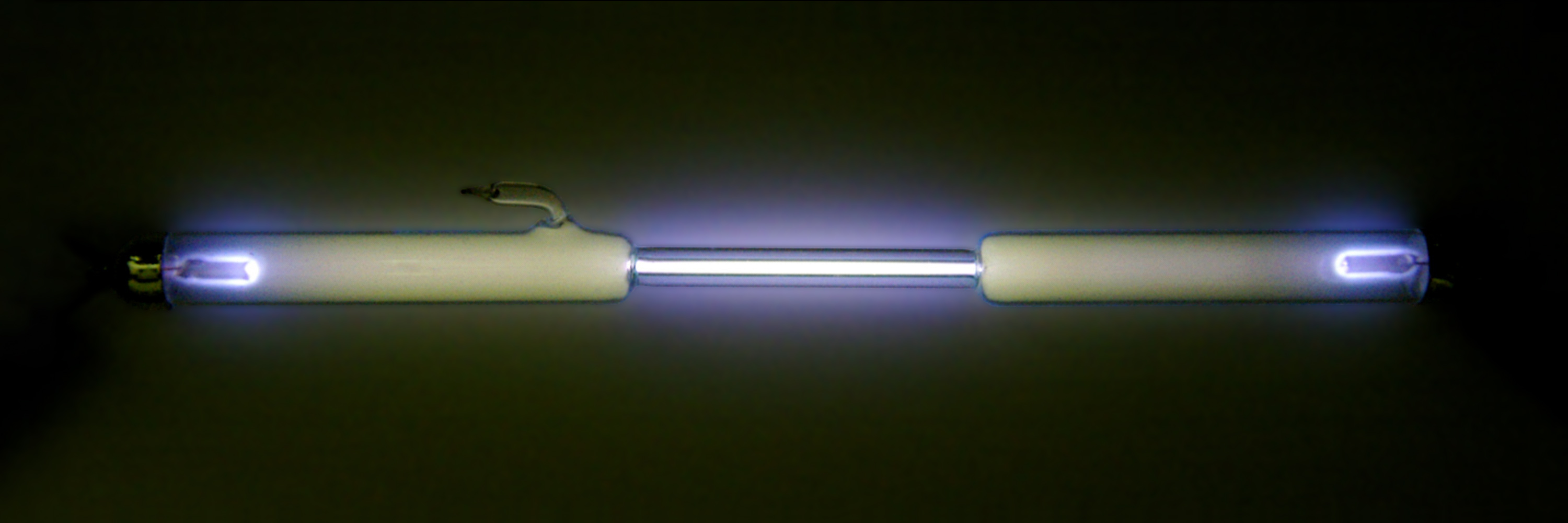

Trioxygen () is usually known as ozone and is a very reactive allotrope of oxygen that is damaging to lung tissue. Ozone is produced in the upper atmosphere when combines with atomic oxygen made by the splitting of by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Since ozone absorbs strongly in the UV region of the spectrum, the ozone layer of the upper atmosphere functions as a protective radiation shield for the planet. Near the Earth's surface, it is a pollutant

A pollutant or novel entity is a substance or energy introduced into the environment that has undesired effects, or adversely affects the usefulness of a resource. These can be both naturally forming (i.e. minerals or extracted compounds like o ...

formed as a by-product of automobile exhaust. At low earth orbit altitudes, sufficient atomic oxygen is present to cause corrosion of spacecraft.

The metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability denotes an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball i ...

molecule tetraoxygen () was discovered in 2001, and was assumed to exist in one of the six phases of solid oxygen. It was proven in 2006 that this phase, created by pressurizing to 20 GPa

Grading in education is the process of applying standardized measurements for varying levels of achievements in a course. Grades can be assigned as letters (usually A through F), as a range (for example, 1 to 6), as a percentage, or as a numbe ...

, is in fact a rhombohedral

In geometry, a rhombohedron (also called a rhombic hexahedron or, inaccurately, a rhomboid) is a three-dimensional figure with six faces which are rhombi. It is a special case of a parallelepiped where all edges are the same length. It can be us ...

cluster. This cluster has the potential to be a much more powerful oxidizer than either or and may therefore be used in rocket fuel

Rocket propellant is the reaction mass of a rocket. This reaction mass is ejected at the highest achievable velocity from a rocket engine to produce thrust. The energy required can either come from the propellants themselves, as with a chemical ...

. A metallic phase was discovered in 1990 when solid oxygen is subjected to a pressure of above 96 GPa and it was shown in 1998 that at very low temperatures, this phase becomes superconducting

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in certain materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic flux fields are expelled from the material. Any material exhibiting these properties is a superconductor. Unlike ...

.

Physical properties

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter, and seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter. At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for freshwater and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Both liquid and solid are clear substances with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter, and seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter. At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for freshwater and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Both liquid and solid are clear substances with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ), named after the 19th-century British physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), is the predominantly elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of th ...

of blue light). High-purity liquid is usually obtained by the fractional distillation of liquefied air. Liquid oxygen may also be condensed from air using liquid nitrogen as a coolant.

Liquid oxygen is a highly reactive substance and must be segregated from combustible materials.

The spectroscopy of molecular oxygen is associated with the atmospheric processes of aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

and airglow

Airglow (also called nightglow) is a faint emission of light by a planetary atmosphere. In the case of Earth's atmosphere, this optical phenomenon causes the night sky never to be completely dark, even after the effects of starlight and diffu ...

. The absorption in the Herzberg continuum and Schumann–Runge bands in the ultraviolet produces atomic oxygen that is important in the chemistry of the middle atmosphere. Excited-state singlet molecular oxygen is responsible for red chemiluminescence in solution.

Table of thermal and physical properties of oxygen (O2) at atmospheric pressure:

Isotopes and stellar origin

helium fusion

The triple-alpha process is a set of nuclear fusion reactions by which three helium-4 nuclei (alpha particles) are transformed into carbon.

Triple-alpha process in stars

Helium accumulates in the cores of stars as a result of the proton–pro ...

process in massive stars but some is made in the neon burning process. 17O is primarily made by the burning of hydrogen into helium during the CNO cycle

The CNO cycle (for carbon–nitrogen–oxygen; sometimes called Bethe–Weizsäcker cycle after Hans Albrecht Bethe and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker) is one of the two known sets of fusion reactions by which stars convert hydrogen to helium, ...

, making it a common isotope in the hydrogen burning zones of stars. Most 18O is produced when 14N (made abundant from CNO burning) captures a 4He nucleus, making 18O common in the helium-rich zones of evolved, massive stars.

Fourteen radioisotope

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transferr ...

s have been characterized. The most stable are 15O with a half-life of 122.24 seconds and 14O with a half-life of 70.606 seconds. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 27 s and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 83 milliseconds. The most common decay mode of the isotopes lighter than 16O is β+ decay to yield nitrogen, and the most common mode for the isotopes heavier than 18O is beta decay to yield fluorine.

Occurrence

Oxygen is the most abundant chemical element by mass in the Earth'sbiosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also ...

, air, sea and land. Oxygen is the third most abundant chemical element in the universe, after hydrogen and helium. Emsley 2001, p. 297 About 0.9% of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

's mass is oxygen. Oxygen constitutes 49.2% of the Earth's crust by mass as part of oxide compounds such as silicon dioxide and is the most abundant element by mass in the Earth's crust. It is also the major component of the world's oceans (88.8% by mass). Oxygen gas is the second most common component of the Earth's atmosphere, taking up 20.8% of its volume and 23.1% of its mass (some 1015 tonnes). Emsley 2001, p. 298Figures given are for values up to above the surface Earth is unusual among the planets of the Solar System in having such a high concentration of oxygen gas in its atmosphere: Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

(with 0.1% by volume) and Venus have much less. The surrounding those planets is produced solely by the action of ultraviolet radiation on oxygen-containing molecules such as carbon dioxide.

The unusually high concentration of oxygen gas on Earth is the result of the

The unusually high concentration of oxygen gas on Earth is the result of the oxygen cycle

Oxygen cycle refers to the movement of oxygen through the atmosphere (air), biosphere (plants and animals) and the lithosphere (the Earth’s crust). The oxygen cycle demonstrates how free oxygen is made available in each of these regions, as wel ...

. This biogeochemical cycle describes the movement of oxygen within and between its three main reservoirs on Earth: the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the lithosphere. The main driving factor of the oxygen cycle is photosynthesis, which is responsible for modern Earth's atmosphere. Photosynthesis releases oxygen into the atmosphere, while respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

, decay, and combustion remove it from the atmosphere. In the present equilibrium, production and consumption occur at the same rate.

Free oxygen also occurs in solution in the world's water bodies. The increased solubility of at lower temperatures (see Physical properties) has important implications for ocean life, as polar oceans support a much higher density of life due to their higher oxygen content. Water polluted with plant nutrients such as nitrates or phosphates may stimulate growth of algae by a process called eutrophication and the decay of these organisms and other biomaterials may reduce the content in eutrophic water bodies. Scientists assess this aspect of water quality by measuring the water's biochemical oxygen demand

Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) is the amount of dissolved oxygen (DO) needed (i.e. demanded) by aerobic biological organisms to break down organic material present in a given water sample at a certain temperature over a specific time period. ...

, or the amount of needed to restore it to a normal concentration. Emsley 2001, p. 301

Analysis

Paleoclimatologists measure the ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in the shells and skeletons of marine organisms to determine the climate millions of years ago (see

Paleoclimatologists measure the ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in the shells and skeletons of marine organisms to determine the climate millions of years ago (see oxygen isotope ratio cycle

Oxygen isotope ratio cycles are cyclical variations in the ratio of the abundance of oxygen with an atomic mass of 18 to the abundance of oxygen with an atomic mass of 16 present in some substances, such as polar ice or calcite in ocean core sampl ...

). Seawater molecules that contain the lighter isotope, oxygen-16, evaporate at a slightly faster rate than water molecules containing the 12% heavier oxygen-18, and this disparity increases at lower temperatures. Emsley 2001, p. 304 During periods of lower global temperatures, snow and rain from that evaporated water tends to be higher in oxygen-16, and the seawater left behind tends to be higher in oxygen-18. Marine organisms then incorporate more oxygen-18 into their skeletons and shells than they would in a warmer climate. Paleoclimatologists also directly measure this ratio in the water molecules of ice core samples as old as hundreds of thousands of years.

Planetary geologists have measured the relative quantities of oxygen isotopes in samples from the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, the Moon, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, and meteorites, but were long unable to obtain reference values for the isotope ratios in the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, believed to be the same as those of the primordial solar nebula. Analysis of a silicon wafer exposed to the solar wind

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles released from the upper atmosphere of the Sun, called the corona. This plasma mostly consists of electrons, protons and alpha particles with kinetic energy between . The composition of the sol ...

in space and returned by the crashed Genesis spacecraft has shown that the Sun has a higher proportion of oxygen-16 than does the Earth. The measurement implies that an unknown process depleted oxygen-16 from the Sun's disk of protoplanetary material prior to the coalescence of dust grains that formed the Earth.

Oxygen presents two spectrophotometric absorption bands peaking at the wavelengths 687 and 760 nm. Some remote sensing scientists have proposed using the measurement of the radiance coming from vegetation canopies in those bands to characterize plant health status from a satellite platform. This approach exploits the fact that in those bands it is possible to discriminate the vegetation's reflectance

The reflectance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in reflecting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is reflected at the boundary. Reflectance is a component of the response of the electronic ...

from its fluorescence, which is much weaker. The measurement is technically difficult owing to the low signal-to-noise ratio and the physical structure of vegetation; but it has been proposed as a possible method of monitoring the carbon cycle from satellites on a global scale.

Biological production and role of O2

Photosynthesis and respiration

thylakoid membrane

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thyla ...

s of photosynthetic organisms and requires the energy of four photons.Thylakoid membranes are part of chloroplasts in algae and plants while they simply are one of many membrane structures in cyanobacteria. In fact, chloroplasts are thought to have evolved from cyanobacteria that were once symbiotic partners with the progenitors of plants and algae. Many steps are involved, but the result is the formation of a proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane, which is used to synthesize adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via photophosphorylation In the process of photosynthesis, the phosphorylation of ADP to form ATP using the energy of sunlight is called photophosphorylation. Cyclic photophosphorylation occurs in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, driven by the main primary source of ...

. Raven 2005, 115–27 The remaining (after production of the water molecule) is released into the atmosphere.Water oxidation is catalyzed by a manganese-containing enzyme complex known as the oxygen evolving complex

The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), also known as the water-splitting complex, is the portion of photosystem II where photo-oxidation of water occurs during the light reactions of photosynthesis. The OEC is surrounded by four core protein subunits ...

(OEC) or water-splitting complex found associated with the lumenal side of thylakoid membranes. Manganese is an important cofactor, and calcium and chloride are also required for the reaction to occur. (Raven 2005)

Oxygen is used in mitochondria in the generation of ATP during oxidative phosphorylation. The reaction for aerobic respiration is essentially the reverse of photosynthesis and is simplified as

: + 6 → 6 + 6 + 2880 kJ/mol

In vertebrates, diffuses through membranes in the lungs and into red blood cells. Hemoglobin binds , changing color from bluish red to bright red ( is released from another part of hemoglobin through the Bohr effect). Other animals use hemocyanin (molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estim ...

and some arthropods) or hemerythrin ( spiders and lobsters). A liter of blood can dissolve 200 cm3 of .

Until the discovery of anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

* Anaerobic adhesive, a bonding a ...

metazoa, oxygen was thought to be a requirement for all complex life.

Reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (). Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

The reduction of molecular oxygen () p ...

, such as superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of t ...

ion () and hydrogen peroxide (), are reactive by-products of oxygen use in organisms. Parts of the immune system of higher organisms create peroxide, superoxide, and singlet oxygen to destroy invading microbes. Reactive oxygen species also play an important role in the hypersensitive response of plants against pathogen attack. Oxygen is damaging to obligately anaerobic organisms, which were the dominant form of early life

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

on Earth until began to accumulate in the atmosphere about 2.5 billion years ago during the Great Oxygenation Event, about a billion years after the first appearance of these organisms.

An adult human at rest inhales 1.8 to 2.4 grams of oxygen per minute. This amounts to more than 6 billion tonnes of oxygen inhaled by humanity per year.(1.8 grams/min/person)×(60 min/h)×(24 h/day)×(365 days/year)×(6.6 billion people)/1,000,000 g/t=6.24 billion tonnes

Living organisms

The free oxygen partial pressure in the body of a living vertebrate organism is highest in therespiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies ...

, and decreases along any arterial system, peripheral tissues, and venous system, respectively. Partial pressure is the pressure that oxygen would have if it alone occupied the volume.

Build-up in the atmosphere

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

evolved, probably about 3.5 billion years ago. Free oxygen first appeared in significant quantities during the Paleoproterozoic

The Paleoproterozoic Era (;, also spelled Palaeoproterozoic), spanning the time period from (2.5–1.6 Ga), is the first of the three sub-divisions ( eras) of the Proterozoic Eon. The Paleoproterozoic is also the longest era of the Earth's ...

eon (between 3.0 and 2.3 billion years ago). Even if there was much dissolved iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

in the oceans when oxygenic photosynthesis was getting more common, it appears the banded iron formation

Banded iron formations (also known as banded ironstone formations or BIFs) are distinctive units of sedimentary rock consisting of alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. They can be up to several hundred meters in thickness ...

s were created by anoxyenic or micro-aerophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria which dominated the deeper areas of the photic zone, while oxygen-producing cyanobacteria covered the shallows. Free oxygen began to outgas from the oceans 3–2.7 billion years ago, reaching 10% of its present level around 1.7 billion years ago.

The presence of large amounts of dissolved and free oxygen in the oceans and atmosphere may have driven most of the extant anaerobic organisms to extinction during the Great Oxygenation Event (''oxygen catastrophe'') about 2.4 billion years ago. Cellular respiration using enables aerobic organisms to produce much more ATP than anaerobic organisms. Cellular respiration of occurs in all eukaryotes, including all complex multicellular organisms such as plants and animals.

Since the beginning of the Cambrian period 540 million years ago, atmospheric levels have fluctuated between 15% and 30% by volume. Towards the end of the Carboniferous period (about 300 million years ago) atmospheric levels reached a maximum of 35% by volume, which may have contributed to the large size of insects and amphibians at this time.

Variations in atmospheric oxygen concentration have shaped past climates. When oxygen declined, atmospheric density dropped, which in turn increased surface evaporation, causing precipitation increases and warmer temperatures.

At the current rate of photosynthesis it would take about 2,000 years to regenerate the entire in the present atmosphere.

Extraterrestrial free oxygen

In the field of astrobiology and in the search for extraterrestrial life oxygen is a strong biosignature. That said it might not be a definite biosignature, being possibly produced abiotically on celestial bodies with processes and conditions (such as a peculiar hydrosphere) which allow free oxygen, like with Europa's and Ganymede's thin oxygen atmospheres.Industrial production

distilling

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distillation is the heating ...

as a vapor while is left as a liquid.

The other primary method of producing is passing a stream of clean, dry air through one bed of a pair of identical zeolite molecular sieves, which absorbs the nitrogen and delivers a gas stream that is 90% to 93% . Simultaneously, nitrogen gas is released from the other nitrogen-saturated zeolite bed, by reducing the chamber operating pressure and diverting part of the oxygen gas from the producer bed through it, in the reverse direction of flow. After a set cycle time the operation of the two beds is interchanged, thereby allowing for a continuous supply of gaseous oxygen to be pumped through a pipeline. This is known as pressure swing adsorption

Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) is a technique used to separate some gas species from a mixture of gases (typically air) under pressure according to the species' molecular characteristics and affinity for an adsorbent material. It operates at ne ...

. Oxygen gas is increasingly obtained by these non- cryogenic technologies (see also the related vacuum swing adsorption).

Oxygen gas can also be produced through electrolysis of water

Electrolysis of water, also known as electrochemical water splitting, is the process of using electricity to decompose water into oxygen and hydrogen gas by electrolysis. Hydrogen gas released in this way can be used as hydrogen fuel, or remi ...

into molecular oxygen and hydrogen. DC electricity must be used: if AC is used, the gases in each limb consist of hydrogen and oxygen in the explosive ratio 2:1. A similar method is the electrocatalytic evolution from oxides and oxoacid

An oxyacid, oxoacid, or ternary acid is an acid that contains oxygen. Specifically, it is a compound that contains hydrogen, oxygen, and at least one other element, with at least one hydrogen atom bonded to oxygen that can dissociate to produce ...

s. Chemical catalysts can be used as well, such as in chemical oxygen generators or oxygen candles that are used as part of the life-support equipment on submarines, and are still part of standard equipment on commercial airliners in case of depressurization emergencies. Another air separation method is forcing air to dissolve through ceramic membranes based on zirconium dioxide by either high pressure or an electric current, to produce nearly pure gas.

Storage

Oxygen storage methods include high-pressure oxygen tanks, cryogenics and chemical compounds. For reasons of economy, oxygen is often transported in bulk as a liquid in specially insulated tankers, since one liter of liquefied oxygen is equivalent to 840 liters of gaseous oxygen at atmospheric pressure and . Such tankers are used to refill bulk liquid-oxygen storage containers, which stand outside hospitals and other institutions that need large volumes of pure oxygen gas. Liquid oxygen is passed through

Oxygen storage methods include high-pressure oxygen tanks, cryogenics and chemical compounds. For reasons of economy, oxygen is often transported in bulk as a liquid in specially insulated tankers, since one liter of liquefied oxygen is equivalent to 840 liters of gaseous oxygen at atmospheric pressure and . Such tankers are used to refill bulk liquid-oxygen storage containers, which stand outside hospitals and other institutions that need large volumes of pure oxygen gas. Liquid oxygen is passed through heat exchanger

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between a source and a working fluid. Heat exchangers are used in both cooling and heating processes. The fluids may be separated by a solid wall to prevent mixing or they may be in direct conta ...

s, which convert the cryogenic liquid into gas before it enters the building. Oxygen is also stored and shipped in smaller cylinders containing the compressed gas; a form that is useful in certain portable medical applications and oxy-fuel welding and cutting.

Applications

Medical

Uptake of from the air is the essential purpose of

Uptake of from the air is the essential purpose of respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

, so oxygen supplementation is used in medicine. Treatment not only increases oxygen levels in the patient's blood, but has the secondary effect of decreasing resistance to blood flow in many types of diseased lungs, easing work load on the heart. Oxygen therapy is used to treat emphysema, pneumonia, some heart disorders ( congestive heart failure), some disorders that cause increased pulmonary artery pressure, and any disease that impairs the body's ability to take up and use gaseous oxygen. Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 510

Treatments are flexible enough to be used in hospitals, the patient's home, or increasingly by portable devices. Oxygen tent

An oxygen tent consists of a canopy placed over the head and shoulders, or over the entire body of a patient to provide oxygen at a higher level than normal. Some devices cover only a part of the face. Oxygen tents are sometimes confused with a ...

s were once commonly used in oxygen supplementation, but have since been replaced mostly by the use of oxygen masks or nasal cannula

The nasal cannula (NC) is a device used to deliver supplemental oxygen or increased airflow to a patient or person in need of respiratory help. This device consists of a lightweight tube which on one end splits into two prongs which are place ...

s.

Hyperbaric (high-pressure) medicine uses special oxygen chambers to increase the partial pressure of around the patient and, when needed, the medical staff. Carbon monoxide poisoning, gas gangrene

Gas gangrene (also known as clostridial myonecrosis and myonecrosis) is a bacterial infection that produces tissue gas in gangrene. This deadly form of gangrene usually is caused by '' Clostridium perfringens'' bacteria. About 1,000 cases of gas ...

, and decompression sickness

Decompression sickness (abbreviated DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompressio ...

(the 'bends') are sometimes addressed with this therapy. Increased concentration in the lungs helps to displace carbon monoxide from the heme group of hemoglobin. Oxygen gas is poisonous to the anaerobic bacteria that cause gas gangrene, so increasing its partial pressure helps kill them. Decompression sickness occurs in divers who decompress too quickly after a dive, resulting in bubbles of inert gas, mostly nitrogen and helium, forming in the blood. Increasing the pressure of as soon as possible helps to redissolve the bubbles back into the blood so that these excess gasses can be exhaled naturally through the lungs. Normobaric oxygen administration at the highest available concentration is frequently used as first aid for any diving injury that may involve inert gas bubble formation in the tissues. There is epidemiological support for its use from a statistical study of cases recorded in a long term database.

Life support and recreational use

An application of as a low-pressure

An application of as a low-pressure breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed ...

is in modern space suit

A space suit or spacesuit is a garment worn to keep a human alive in the harsh environment of outer space, vacuum and temperature extremes. Space suits are often worn inside spacecraft as a safety precaution in case of loss of cabin pressure, ...

s, which surround their occupant's body with the breathing gas. These devices use nearly pure oxygen at about one-third normal pressure, resulting in a normal blood partial pressure of . This trade-off of higher oxygen concentration for lower pressure is needed to maintain suit flexibility.

Scuba and surface-supplied underwater divers

This is a list of underwater divers whose exploits have made them notable.

Underwater divers are people who take part in underwater diving activities – Underwater diving is practiced as part of an occupation, or for recreation, where t ...

and submariners also rely on artificially delivered . Submarines, submersibles and atmospheric diving suits

An atmospheric diving suit (ADS) is a small one-person articulated submersible which resembles a suit of armour, with elaborate pressure joints to allow articulation while maintaining an internal pressure of one atmosphere. An ADS can enable di ...