Otto Hahn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

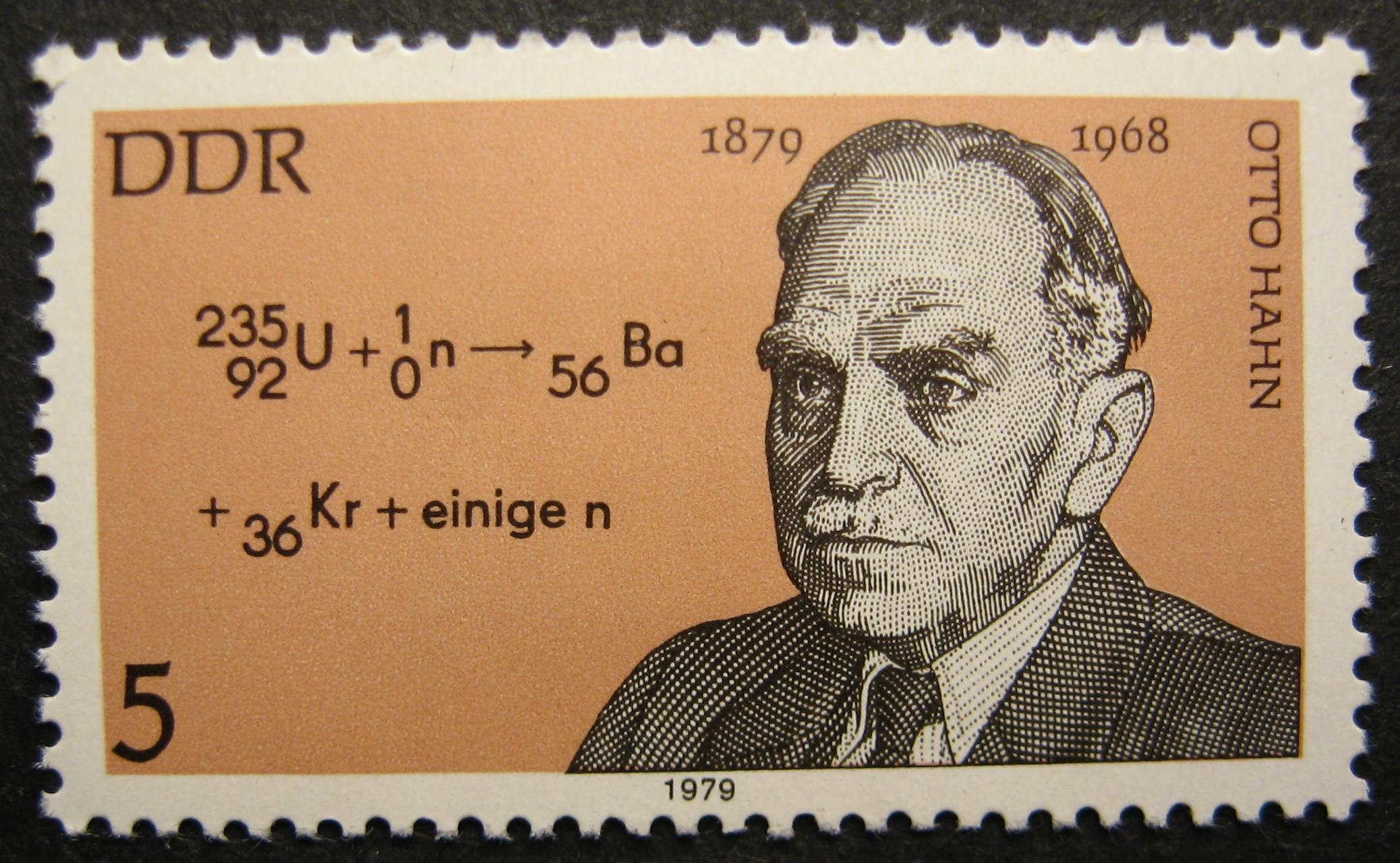

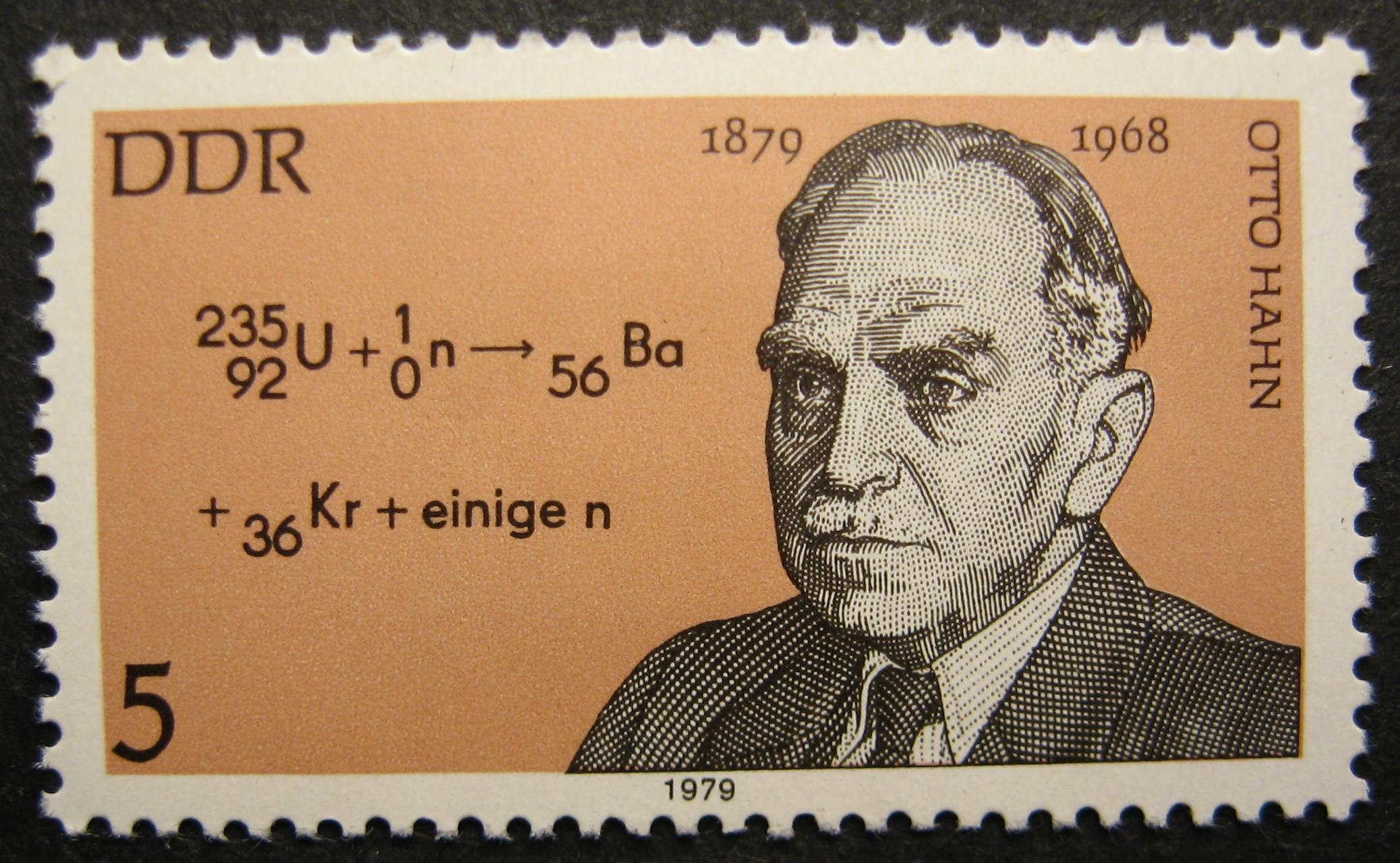

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German

Hahn's intention was still to work in industry. He received an offer of employment from Eugen Fischer, the director of (and the father of organic chemist

Hahn's intention was still to work in industry. He received an offer of employment from Eugen Fischer, the director of (and the father of organic chemist  Hahn published his results in the ''

Hahn published his results in the ''

In 1906, Hahn returned to Germany, where Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop (''Holzwerkstatt'') in the basement of the Chemical Institute to use as a laboratory. Hahn equipped it with

In 1906, Hahn returned to Germany, where Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop (''Holzwerkstatt'') in the basement of the Chemical Institute to use as a laboratory. Hahn equipped it with  Physicists were more accepting of Hahn's work, and he began attending a colloquium at the Physics Institute conducted by Heinrich Rubens. It was at one of these colloquia where, on 28 September 1907, he made the acquaintance of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Almost the same age as himself, she was only the second woman to receive a doctorate from the

Physicists were more accepting of Hahn's work, and he began attending a colloquium at the Physics Institute conducted by Heinrich Rubens. It was at one of these colloquia where, on 28 September 1907, he made the acquaintance of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Almost the same age as himself, she was only the second woman to receive a doctorate from the

Harriet Brooks observed a radioactive recoil in 1904, but interpreted it wrongly. Hahn and Meitner succeeded in demonstrating the radioactive recoil incident to

Harriet Brooks observed a radioactive recoil in 1904, but interpreted it wrongly. Hahn and Meitner succeeded in demonstrating the radioactive recoil incident to

With a regular income, Hahn was now able to contemplate marriage. In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin, Hahn met (1887–1968), a student at the

With a regular income, Hahn was now able to contemplate marriage. In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin, Hahn met (1887–1968), a student at the

In 1913, chemists Frederick Soddy and

In 1913, chemists Frederick Soddy and

With the discovery of protactinium, most of the decay chains of uranium had been mapped. When Hahn returned to his work after the war, he looked back over his 1914 results, and considered some anomalies that had been dismissed or overlooked. He dissolved uranium salts in a hydrofluoric acid solution with tantalic acid. First the tantalum in the ore was precipitated, then the protactinium. In addition to the uranium X1 (thorium-234) and uranium X2 (protactinium-234), Hahn detected traces of a radioactive substance with a half life of between 6 and 7 hours. There was one isotope known to have a half life of 6.2 hours, mesothorium II (actinium-228). This was not in any probable decay chain, but it could have been contamination, as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry had experimented with it. Hahn and Meitner demonstrated in 1919 that when actinium is treated with hydrofluoric acid, it remains in the insoluble residue. Since mesothorium II was an isotope of actinium, the substance was not mesothorium II; it was protactinium.

Hahn was now confident enough that he had found something that he named his new isotope "uranium Z", and in February 1921, he published the first report on his discovery.

Hahn determined that uranium Z had a half life of around 6.7 hours (with a two per cent margin of error) and that when uranium X1 decayed, it became uranium X2 about 99.75 per cent of the time, and uranium Z around 0.25 per cent of the time. He found that the proportion of uranium X to uranium Z extracted from several kilograms of

With the discovery of protactinium, most of the decay chains of uranium had been mapped. When Hahn returned to his work after the war, he looked back over his 1914 results, and considered some anomalies that had been dismissed or overlooked. He dissolved uranium salts in a hydrofluoric acid solution with tantalic acid. First the tantalum in the ore was precipitated, then the protactinium. In addition to the uranium X1 (thorium-234) and uranium X2 (protactinium-234), Hahn detected traces of a radioactive substance with a half life of between 6 and 7 hours. There was one isotope known to have a half life of 6.2 hours, mesothorium II (actinium-228). This was not in any probable decay chain, but it could have been contamination, as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry had experimented with it. Hahn and Meitner demonstrated in 1919 that when actinium is treated with hydrofluoric acid, it remains in the insoluble residue. Since mesothorium II was an isotope of actinium, the substance was not mesothorium II; it was protactinium.

Hahn was now confident enough that he had found something that he named his new isotope "uranium Z", and in February 1921, he published the first report on his discovery.

Hahn determined that uranium Z had a half life of around 6.7 hours (with a two per cent margin of error) and that when uranium X1 decayed, it became uranium X2 about 99.75 per cent of the time, and uranium Z around 0.25 per cent of the time. He found that the proportion of uranium X to uranium Z extracted from several kilograms of

After

After  In May 1937, they issued parallel reports, one in ''Zeitschrift für Physik'' with Meitner as the principal author, and one in ''Chemische Berichte'' with Hahn as the principal author. Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: ''Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion'' ("Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion"); Meitner was increasingly uncertain. She considered the possibility that the reactions were from different isotopes of uranium; three were known: uranium-238, uranium-235 and uranium-234. However, when she calculated the

In May 1937, they issued parallel reports, one in ''Zeitschrift für Physik'' with Meitner as the principal author, and one in ''Chemische Berichte'' with Hahn as the principal author. Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: ''Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion'' ("Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion"); Meitner was increasingly uncertain. She considered the possibility that the reactions were from different isotopes of uranium; three were known: uranium-238, uranium-235 and uranium-234. However, when she calculated the  In her reply, Meitner concurred. "At the moment, the interpretation of such a thoroughgoing breakup seems very difficult to me, but in nuclear physics we have experienced so many surprises, that one cannot unconditionally say: 'it is impossible'." On 22 December 1938, Hahn sent a manuscript to '' Naturwissenschaften'' reporting their radiochemical results, which were published on 6 January 1939. On 27 December, Hahn telephoned the editor of ''Naturwissenschaften'' and requested an addition to the article, speculating that some

In her reply, Meitner concurred. "At the moment, the interpretation of such a thoroughgoing breakup seems very difficult to me, but in nuclear physics we have experienced so many surprises, that one cannot unconditionally say: 'it is impossible'." On 22 December 1938, Hahn sent a manuscript to '' Naturwissenschaften'' reporting their radiochemical results, which were published on 6 January 1939. On 27 December, Hahn telephoned the editor of ''Naturwissenschaften'' and requested an addition to the article, speculating that some

They were relocated to the Château de Facqueval in

They were relocated to the Château de Facqueval in

Under Nazi rule, Germans had been forbidden to accept Nobel prizes after the

Under Nazi rule, Germans had been forbidden to accept Nobel prizes after the

The suicide of

The suicide of

In early 1954, he wrote the article "Cobalt 60 – Danger or Blessing for Mankind?", about the misuse of atomic energy, which was widely reprinted and transmitted in the radio in Germany, Norway, Austria, and Denmark, and in an English version worldwide via the BBC. The international reaction was encouraging. The following year he initiated and organized the Mainau Declaration of 1955, in which he and a number of international Nobel Prize-winners called attention to the dangers of atomic weapons and warned the nations of the world urgently against the use of "force as a final resort", and which was issued a week after the similar Russell-Einstein Manifesto. In 1956, Hahn repeated his appeal with the signature of 52 of his Nobel colleagues from all parts of the world.

Hahn was also instrumental in and one of the authors of the Göttinger Manifest, Göttingen Manifesto of 13 April 1957, in which, together with 17 leading German atomic scientists, he protested against a proposed nuclear arming of the West German armed forces (''Bundeswehr''). This resulted in Hahn receiving an invitation to meet with the Chancellor of Germany, Konrad Adenauer and other senior officials, including the Defense Minister, Franz Josef Strauss, and Generals Hans Speidel and Adolf Heusinger (who both had been generals in the Nazi era). The two generals argued that the ''Bundeswehr'' needed nuclear weapons, and Adenauer accepted their advice. A communique was drafted that said that the Federal Republic did not manufacture nuclear weapons, and would not ask its scientists to do so. Instead, the German forces were equipped with US nuclear weapons.

In early 1954, he wrote the article "Cobalt 60 – Danger or Blessing for Mankind?", about the misuse of atomic energy, which was widely reprinted and transmitted in the radio in Germany, Norway, Austria, and Denmark, and in an English version worldwide via the BBC. The international reaction was encouraging. The following year he initiated and organized the Mainau Declaration of 1955, in which he and a number of international Nobel Prize-winners called attention to the dangers of atomic weapons and warned the nations of the world urgently against the use of "force as a final resort", and which was issued a week after the similar Russell-Einstein Manifesto. In 1956, Hahn repeated his appeal with the signature of 52 of his Nobel colleagues from all parts of the world.

Hahn was also instrumental in and one of the authors of the Göttinger Manifest, Göttingen Manifesto of 13 April 1957, in which, together with 17 leading German atomic scientists, he protested against a proposed nuclear arming of the West German armed forces (''Bundeswehr''). This resulted in Hahn receiving an invitation to meet with the Chancellor of Germany, Konrad Adenauer and other senior officials, including the Defense Minister, Franz Josef Strauss, and Generals Hans Speidel and Adolf Heusinger (who both had been generals in the Nazi era). The two generals argued that the ''Bundeswehr'' needed nuclear weapons, and Adenauer accepted their advice. A communique was drafted that said that the Federal Republic did not manufacture nuclear weapons, and would not ask its scientists to do so. Instead, the German forces were equipped with US nuclear weapons.

On 13 November 1957, in the ''Konzerthaus'' (Concert Hall) in Vienna, Hahn warned of the "dangers of A- and H-bomb-experiments", and declared that "today war is no means of politics anymore – it will only destroy all countries in the world". His highly acclaimed speech was transmitted internationally by the Austrian radio, Österreichischer Rundfunk (ÖR). On 28 December 1957, Hahn repeated his appeal in an English translation for the Bulgarian Radio in Sofia, which was broadcast in all Warsaw pact states.

In 1959 Hahn co-founded in Berlin the

On 13 November 1957, in the ''Konzerthaus'' (Concert Hall) in Vienna, Hahn warned of the "dangers of A- and H-bomb-experiments", and declared that "today war is no means of politics anymore – it will only destroy all countries in the world". His highly acclaimed speech was transmitted internationally by the Austrian radio, Österreichischer Rundfunk (ÖR). On 28 December 1957, Hahn repeated his appeal in an English translation for the Bulgarian Radio in Sofia, which was broadcast in all Warsaw pact states.

In 1959 Hahn co-founded in Berlin the

Hahn was shot in the back by a disgruntled inventor in October 1951, injured in a motor vehicle accident in 1952, and had a minor heart attack in 1953. In 1962, he published a book, ''Vom Radiothor zur Uranspaltung'' (''From the radiothor to Uranium fission''). It was released in English in 1966 with the title ''Otto Hahn: A Scientific Autobiography'', with an introduction by Glenn Seaborg. The success of this book may have prompted him to write another, fuller autobiography, ''Otto Hahn. Mein Leben'', but before it could be published, he fractured one of the vertebrae in his neck while getting out of a car. He gradually became weaker and died in Göttingen on 28 July 1968. His wife Edith survived him by only a fortnight. He was buried in the Stadtfriedhof (Göttingen), Stadtfriedhof in Göttingen.

The day after his death, the Max Planck Society published the following obituary notice in all the major newspapers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland:

Fritz Strassmann wrote:

Otto Robert Frisch recalled:

The

Hahn was shot in the back by a disgruntled inventor in October 1951, injured in a motor vehicle accident in 1952, and had a minor heart attack in 1953. In 1962, he published a book, ''Vom Radiothor zur Uranspaltung'' (''From the radiothor to Uranium fission''). It was released in English in 1966 with the title ''Otto Hahn: A Scientific Autobiography'', with an introduction by Glenn Seaborg. The success of this book may have prompted him to write another, fuller autobiography, ''Otto Hahn. Mein Leben'', but before it could be published, he fractured one of the vertebrae in his neck while getting out of a car. He gradually became weaker and died in Göttingen on 28 July 1968. His wife Edith survived him by only a fortnight. He was buried in the Stadtfriedhof (Göttingen), Stadtfriedhof in Göttingen.

The day after his death, the Max Planck Society published the following obituary notice in all the major newspapers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland:

Fritz Strassmann wrote:

Otto Robert Frisch recalled:

The

Hahn became the honorary president of the Max Planck Society in 1962.

* He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1957, Foreign Member of the Royal Society (1957).

*His honorary memberships of foreign academies and scientific societies included:

** the Romanian Physical Society in Bucharest,

** the Royal Spanish Society for Chemistry and Physics and the Spanish National Research Council,

** and the Academies in Allahabad, Bangalore, Berlin, Boston, Bucharest, Copenhagen, Göttingen, Halle, Helsinki, Lisbon, Madrid, Mainz, Munich, Rome, Stockholm, Vatican, and Vienna.

He was an honorary fellow of University College London,

* and an honorary citizen of the cities of Frankfurt am Main and Göttingen in 1959,

* and of Berlin (1968).

* Hahn was made an Officer of the ''Ordre National de la Légion d'Honneur'' of France (1959),

* and was awarded the Grand Cross First Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1959).

* In 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson and the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) awarded Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann the Enrico Fermi Award. The diploma for Hahn bore the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies culminating in the discovery of fission."

* He received honorary doctorates from

** the University of Gottingen,

** the Technische Universität Darmstadt,

** the University of Frankfurt in 1949,

** and the University of Cambridge in 1957.

Objects named after Hahn include:

* Otto Hahn (ship), NS ''Otto Hahn'', the only European nuclear-powered civilian ship (1964),

* a Hahn (crater), crater on the Moon (shared with his namesake Friedrich von Hahn),

* and the asteroid ''19126 Ottohahn'',

* the Otto Hahn Prize of both the German Chemical and Physical Societies and the city of Frankfurt/Main,

* the Otto Hahn Medal and the Otto Hahn Award of the Max Planck Society,

* and the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin (1988).

Proposals were made at various times, first in 1971 by American chemists, that the newly synthesised element 105 should be named ''hahnium'' in Hahn's honour, but in 1997 the IUPAC named it dubnium, after the Russian research centre in Dubna. In 1992 element 108 was discovered by a German research team, and they proposed the name hassium (after Hesse). In spite of the long-standing convention to give the discoverer the right to suggest a name, a 1994 IUPAC committee recommended that it be named ''hahnium''. After protests from the German discoverers, the name hassium (Hs) was adopted internationally in 1997.

Hahn became the honorary president of the Max Planck Society in 1962.

* He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1957, Foreign Member of the Royal Society (1957).

*His honorary memberships of foreign academies and scientific societies included:

** the Romanian Physical Society in Bucharest,

** the Royal Spanish Society for Chemistry and Physics and the Spanish National Research Council,

** and the Academies in Allahabad, Bangalore, Berlin, Boston, Bucharest, Copenhagen, Göttingen, Halle, Helsinki, Lisbon, Madrid, Mainz, Munich, Rome, Stockholm, Vatican, and Vienna.

He was an honorary fellow of University College London,

* and an honorary citizen of the cities of Frankfurt am Main and Göttingen in 1959,

* and of Berlin (1968).

* Hahn was made an Officer of the ''Ordre National de la Légion d'Honneur'' of France (1959),

* and was awarded the Grand Cross First Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1959).

* In 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson and the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) awarded Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann the Enrico Fermi Award. The diploma for Hahn bore the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies culminating in the discovery of fission."

* He received honorary doctorates from

** the University of Gottingen,

** the Technische Universität Darmstadt,

** the University of Frankfurt in 1949,

** and the University of Cambridge in 1957.

Objects named after Hahn include:

* Otto Hahn (ship), NS ''Otto Hahn'', the only European nuclear-powered civilian ship (1964),

* a Hahn (crater), crater on the Moon (shared with his namesake Friedrich von Hahn),

* and the asteroid ''19126 Ottohahn'',

* the Otto Hahn Prize of both the German Chemical and Physical Societies and the city of Frankfurt/Main,

* the Otto Hahn Medal and the Otto Hahn Award of the Max Planck Society,

* and the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin (1988).

Proposals were made at various times, first in 1971 by American chemists, that the newly synthesised element 105 should be named ''hahnium'' in Hahn's honour, but in 1997 the IUPAC named it dubnium, after the Russian research centre in Dubna. In 1992 element 108 was discovered by a German research team, and they proposed the name hassium (after Hesse). In spite of the long-standing convention to give the discoverer the right to suggest a name, a 1994 IUPAC committee recommended that it be named ''hahnium''. After protests from the German discoverers, the name hassium (Hs) was adopted internationally in 1997.

Otto Hahn – winner of the Enrico Fermi Award 1966

U.S Government, Department of Energy * including the Nobel Lecture on 13 December 1946 ''From the Natural Transmutations of Uranium to Its Artificial Fission''

by Professor Arne Westgren, Stockholm.

BR, 2008

Author: Dr. Anne Hardy (Pro-Physik, 2004)

Otto Hahn (1879–1968) – The discovery of fission

Visit Berlin, 2011.

Author: Dr Edmund Neubauer (Translation: Brigitte Hippmann) – Website of the Otto Hahn Gymnasium (OHG), 2007.

Otto Hahn Award

Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold

Website of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin

Otto Hahn Medal

Helmholtz-Zentrum, Berlin 2011.

Otto Hahn heads a delegation to Israel 1959

Website of the Max Planck Society, 2011.

Otto Hahn – A Life for Science, Humanity and Peace

Hiroshima University Peace Lecture, held by Dietrich Hahn, 2 October 2013.

Otto Hahn – Discoverer of nuclear fission, grandfather of the Atombomb

GMX, Switzerland, 17 December 2013. Author: Marinus Brandl. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hahn, Otto Otto Hahn, Otto Hahn 1879 births 1968 deaths 20th-century German chemists Cornell University faculty Discoverers of chemical elements Enrico Fermi Award recipients Faraday Lecturers Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign Fellows of the Indian National Science Academy Foreign Members of the Royal Society Free University of Berlin faculty German anti–nuclear weapons activists German autobiographers German humanitarians German Army personnel of World War I German Nobel laureates German pacifists Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Honorary members of the Romanian Academy Honorary Officers of the Order of the British Empire Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Humboldt University of Berlin faculty Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni Max Planck Society people Members of the Austrian Academy of Sciences Members of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences Members of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Nobel laureates in Chemistry Nuclear chemists Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Operation Epsilon Scientists from Frankfurt People from Hesse-Nassau Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) University of Marburg alumni Winners of the Max Planck Medal Rare earth scientists Max Planck Institute directors

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry

Radiochemistry is the chemistry of radioactive materials, where radioactive isotopes of elements are used to study the properties and chemical reactions of non-radioactive isotopes (often within radiochemistry the absence of radioactivity leads t ...

. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry

Nuclear chemistry is the sub-field of chemistry dealing with radioactivity, nuclear processes, and transformations in the nuclei of atoms, such as nuclear transmutation and nuclear properties.

It is the chemistry of radioactive elements such as ...

and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner discovered radioactive isotopes of radium

Radium (88Ra) has no stable or nearly stable isotopes, and thus a standard atomic weight cannot be given. The longest lived, and most common, isotope of radium is 226Ra with a half-life of . 226Ra occurs in the decay chain of 238U (often referred ...

, thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

, protactinium

Protactinium (formerly protoactinium) is a chemical element with the symbol Pa and atomic number 91. It is a dense, silvery-gray actinide metal which readily reacts with oxygen, water vapor and inorganic acids. It forms various chemical compounds ...

and uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

. He also discovered the phenomena of atomic recoil Atomic recoil is the result of the interaction of an atom with an energetic elementary particle, when the momentum of the interacting particle is transferred to the atom as whole without altering non-translational degrees of freedom of the atom. ...

and nuclear isomerism

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy higher energy levels than in the ground state of the same nucleus. "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have ha ...

, and pioneered rubidium–strontium dating

The rubidium-strontium dating method is a radiometric dating technique, used by scientists to determine the age of rocks and minerals from their content of specific isotopes of rubidium (87Rb) and strontium (87Sr, 86Sr). One of the two naturally ...

. In 1938, Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

discovered nuclear fission, for which Hahn received the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

. Nuclear fission was the basis for nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

s and nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s.

A graduate of the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

, Hahn studied under Sir William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (; 2 October 1852 – 23 July 1916) was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous element ...

at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

and at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

in Montreal under Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

, where he discovered several new radioactive isotopes. He returned to Germany in 1906; Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fischer projection, a symbolic way of draw ...

placed a former woodworking shop in the basement of the Chemical Institute at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

at his disposal to use as a laboratory. Hahn completed his habilitation in the spring of 1907 and became a '' Privatdozent''. In 1912, he became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. Working with the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner in the building that now bears their names, he made a series of groundbreaking discoveries, culminating with her isolation of the longest-lived isotope of protactinium in 1918.

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he served with a ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortificatio ...

'' regiment on the Western Front, and with the chemical warfare unit headed by Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber (; 9 December 186829 January 1934) was a German chemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method used in industry to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydroge ...

on the Western, Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

fronts, earning the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

(2nd Class) for his part in the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (french: Première Bataille des Flandres; german: Erste Flandernschlacht – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the Firs ...

. After the war he became the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, while remaining in charge of his own department. Between 1934 and 1938, he worked with Strassmann and Meitner on the study of isotopes created through the neutron bombardment of uranium and thorium, which led to the discovery of nuclear fission. He was an opponent of national socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

and the persecution of Jews

The persecution of Jews has been a major event in Jewish history, prompting shifting waves of refugees and the formation of diaspora communities. As early as 605 BCE, Jews who lived in the Neo-Babylonian Empire were persecuted and deported. ...

by the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

that caused the removal of many of his colleagues, including Meitner, who was forced to flee Germany in 1938. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, he worked on the German nuclear weapons program

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through sev ...

, cataloguing the fission products of uranium. As a consequence, at the end of the war he was arrested by the Allied forces; he was incarcerated in Farm Hall

A farm (also called an agricultural holding) is an area of land that is devoted primarily to agricultural processes with the primary objective of producing food and other crops; it is the basic facility in food production. The name is used fo ...

with nine other German scientists, from July 1945 to January 1946.

Hahn served as the last president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science in 1946 and as the founding president of its successor, the Max Planck Society from 1948 to 1960. In 1959 he co-founded in Berlin the Federation of German Scientists The Federation of German Scientists - VDW (Vereinigung Deutscher Wissenschaftler e. V.) is a German non-governmental organization.

History

Since its founding 1959 by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Otto Hahn, Max Born and further prominent nuclea ...

, a non-governmental organization, which has been committed to the ideal of responsible science. As he worked to rebuild German science, he became one of the most influential and respected citizens of the post-war West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

.

History

Early life

Otto Hahn was born inFrankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

on 8 March 1879, the youngest son of Heinrich Hahn (1845–1922), a prosperous glazier

A glazier is a tradesman responsible for cutting, installing, and removing glass (and materials used as substitutes for glass, such as some plastics).Elizabeth H. Oakes, ''Ferguson Career Resource Guide to Apprenticeship Programs'' ( Infobase: ...

(and founder of the Glasbau Hahn company), and Charlotte Hahn Giese (1845–1905). He had an older half-brother Karl, his mother's son from her previous marriage, and two older brothers, Heiner and Julius. The family lived above his father's workshop. The younger three boys were educated at ''Klinger Oberrealschule'' in Frankfurt. At the age of 15, he began to take a special interest in chemistry, and carried out simple experiments in the laundry room of the family home. His father wanted Otto to study architecture, as he had built or acquired several residential and business properties, but Otto persuaded him that his ambition was to become an industrial chemist

The chemical industry comprises the companies that produce industrial chemicals. Central to the modern world economy, it converts raw materials (oil, natural gas, air, water, metals, and minerals) into more than 70,000 different products. The ...

.

In 1897, after taking his '' Abitur'', Hahn began to study chemistry at the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

. His subsidiary subjects were mathematics, physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, mineralogy and philosophy. Hahn joined the Students' Association of Natural Sciences and Medicine, a student fraternity and a forerunner of today's ''Landsmannschaft Nibelungi'' ( Coburger Convent der akademischen Landsmannschaften und Turnerschaften). He spent his third and fourth semesters at the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It is Germany's sixth-oldest university in continuous operatio ...

, studying organic chemistry under Adolf von Baeyer

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer (; 31 October 1835 – 20 August 1917) was a German chemist who synthesised indigo and developed a nomenclature for cyclic compounds (that was subsequently extended and adopted as part of the IUPAC org ...

, physical chemistry under Friedrich Wilhelm Muthmann, and inorganic chemistry under Karl Andreas Hofmann. In 1901, Hahn received his doctorate in Marburg for a dissertation entitled "On Bromine Derivates of Isoeugenol", a topic in classical organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, ...

. He completed his one-year military service (instead of the usual two because he had a doctorate) in the 81st Infantry Regiment, but unlike his brothers, did not apply for a commission. He then returned to the University of Marburg, where he worked for two years as assistant to his doctoral supervisor, ''Geheimrat

''Geheimrat'' was the title of the highest advising officials at the Imperial, royal or princely courts of the Holy Roman Empire, who jointly formed the ''Geheimer Rat'' reporting to the ruler. The term remained in use during subsequent monarchic r ...

'' professor Theodor Zincke.

Discovery of radio thorium, and other "new elements"

Hahn's intention was still to work in industry. He received an offer of employment from Eugen Fischer, the director of (and the father of organic chemist

Hahn's intention was still to work in industry. He received an offer of employment from Eugen Fischer, the director of (and the father of organic chemist Hans Fischer

Hans Fischer (; 27 July 1881 – 31 March 1945) was a German organic chemist and the recipient of the 1930 Nobel Prize for Chemistry "for his researches into the constitution of haemin and chlorophyll and especially for his synthesis of ha ...

), but a condition of employment was that Hahn had to have lived in another country and have a reasonable command of another language. With this in mind, and to improve his knowledge of English, Hahn took up a post at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

in 1904, working under Sir William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (; 2 October 1852 – 23 July 1916) was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous element ...

, who was known for having discovered the inert gas

An inert gas is a gas that does not readily undergo chemical reactions with other chemical substances and therefore does not readily form chemical compounds. The noble gases often do not react with many substances and were historically referred to ...

es. Here Hahn worked on radiochemistry

Radiochemistry is the chemistry of radioactive materials, where radioactive isotopes of elements are used to study the properties and chemical reactions of non-radioactive isotopes (often within radiochemistry the absence of radioactivity leads t ...

, at that time a very new field. In early 1905, in the course of his work with salts of radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rathe ...

, Hahn discovered a new substance he called radiothorium

Thorium (90Th) has seven naturally occurring isotopes but none are stable. One isotope, 232Th, is ''relatively'' stable, with a half-life of 1.405×1010 years, considerably longer than the age of the Earth, and even slightly longer than the gene ...

(thorium-228), which at that time was believed to be a new radioactive

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is consi ...

element. (In fact, it was an isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numb ...

of the known element thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

; the concept of an isotope, along with the term, was only coined in 1913, by the British chemist Frederick Soddy

Frederick Soddy FRS (2 September 1877 – 22 September 1956) was an English radiochemist who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions. He also prov ...

).

Ramsay was enthusiastic when yet another new element was found in his institute, and he intended to announce the discovery in a correspondingly suitable way. In accordance with tradition this was done before the committee of the venerable Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. At the session of the Royal Society on 16 March 1905 Ramsay communicated Hahn's discovery of radiothorium. The '' Daily Telegraph'' informed its readers:

Hahn published his results in the ''

Hahn published his results in the ''Proceedings of the Royal Society

''Proceedings of the Royal Society'' is the main research journal of the Royal Society. The journal began in 1831 and was split into two series in 1905:

* Series A: for papers in physical sciences and mathematics.

* Series B: for papers in life s ...

'' on 24 May 1905. It was the first of over 250 scientific publications of Otto Hahn in the field of radiochemistry. At the end of his time in London, Ramsay asked Hahn about his plans for the future, and Hahn told him about the job offer from Kalle & Co. Ramsay told him radiochemistry had a bright future, and that someone who had discovered a new radioactive element should go to the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

. Ramsay wrote to Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fischer projection, a symbolic way of draw ...

, the head of the chemistry institute there, who replied that Hahn could work in his laboratory, but could not be a '' Privatdozent'' because radiochemistry was not taught there. At this point, Hahn decided that he first needed to know more about the subject, so he wrote to the leading expert on the field, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

. Rutherford agreed to take Hahn on as an assistant, and Hahn's parents undertook to pay Hahn's expenses.

From September 1905 until mid-1906, Hahn worked with Rutherford's group in the basement of the Macdonald Physics Building at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

in Montreal. There was some scepticism about the existence of radiothorium, which Bertram Boltwood memorably described as a compound of thorium X and stupidity. Boltwood was soon convinced that it did exist, although he and Hahn differed on what its half life was. William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist, chemist, mathematician, and active sportsman who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nob ...

and Richard Kleeman

Richard Daniel Kleeman (20 January 1875 – 10 October 1932) was an Australian physicist. With William Henry Bragg he discovered that the alpha particles emitted from particular radioactive substances always had the same energy, providing a new w ...

had noted that the alpha particles emitted from radioactive substances always had the same energy, providing a second way of identifying them, so Hahn set about measuring the alpha particle emissions of radiothorium. In the process, he found that a precipitation of thorium A (polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

-216) and thorium B (lead-212) also contained a short-lived "element", which he named thorium C (which was later identified as polonium-212). Hahn was unable to separate it, and concluded that it had a very short half life (it is about 300 ns). He also identified radioactinium (thorium-227) and radium D (later identified as lead-210). Rutherford remarked that: "Hahn has a special nose for discovering new elements."

Discovery of mesothorium I

In 1906, Hahn returned to Germany, where Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop (''Holzwerkstatt'') in the basement of the Chemical Institute to use as a laboratory. Hahn equipped it with

In 1906, Hahn returned to Germany, where Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop (''Holzwerkstatt'') in the basement of the Chemical Institute to use as a laboratory. Hahn equipped it with electroscope

The electroscope is an early scientific instrument used to detect the presence of electric charge on a body. It detects charge by the movement of a test object due to the Coulomb electrostatic force on it. The amount of charge on an object is ...

s to measure alpha and beta particles and gamma rays

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

. In Montreal these had been made from discarded coffee tins; Hahn made the ones in Berlin from brass, with aluminium strips insulated with amber. These were charged with hard rubber sticks that he rubbed then against the sleeves of his suit. It was not possible to conduct research in the wood shop, but Alfred Stock

Alfred Stock (July 16, 1876 – August 12, 1946) was a German inorganic chemist. He did pioneering research on the hydrides of boron and silicon, coordination chemistry, mercury, and mercury poisoning. The German Chemical Society's Alfred-Stoc ...

, the head of the inorganic chemistry department, let Hahn use a space in one of his two private laboratories. Hahn purchased two milligrams of radium from Friedrich Oskar Giesel

Friedrich Oskar Giesel (20 May 1852 – 13 November 1927, known as Fritz) was a German organic chemist. During his work in a quinine factory in the late 1890s, he started to work on the at-that-time-new field of radiochemistry and started the ...

, the discoverer of emanium (radon), for 100 marks a milligram, and obtained thorium for free from Otto Knöfler, whose Berlin firm was a major producer of thorium products.

In the space of a few months Hahn discovered mesothorium I (radium-228), mesothorium II (actinium-228), and – independently from Boltwood – the mother substance of radium, ionium (later identified as thorium-230

Thorium (90Th) has seven naturally occurring isotopes but none are stable. One isotope, 232Th, is ''relatively'' stable, with a half-life of 1.405×1010 years, considerably longer than the age of the Earth, and even slightly longer than the gene ...

). In subsequent years, mesothorium I assumed great importance because, like radium-226 (discovered by Pierre

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

and Marie Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first ...

), it was ideally suited for use in medical radiation treatment, but cost only half as much to manufacture. Along the way, Hahn determined that just as he was unable to separate thorium from radiothorium, so he could not separate mesothorium from radium.

Hahn completed his habilitation in the spring of 1907, and became a ''Privatdozent''. A thesis was not required; the Chemical Institute accepted one of his publications on radioactivity instead. Most of the organic chemists at the Chemical Institute did not regard Hahn's work as real chemistry. Fischer objected to Hahn's contention in his habilitation colloquium that many radioactive substances existed in such tiny amounts that they could only be detected by their radioactivity, venturing that he had always been able to detect substances with his keen sense of smell, but soon gave in. One department head remarked: "it is incredible what one gets to be a ''Privatdozent'' these days!"

Physicists were more accepting of Hahn's work, and he began attending a colloquium at the Physics Institute conducted by Heinrich Rubens. It was at one of these colloquia where, on 28 September 1907, he made the acquaintance of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Almost the same age as himself, she was only the second woman to receive a doctorate from the

Physicists were more accepting of Hahn's work, and he began attending a colloquium at the Physics Institute conducted by Heinrich Rubens. It was at one of these colloquia where, on 28 September 1907, he made the acquaintance of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Almost the same age as himself, she was only the second woman to receive a doctorate from the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich hist ...

, and had already published two papers on radioactivity. Rubens suggested her as a possible collaborator. So began the thirty-year collaboration and lifelong close friendship between the two scientists.

In Montreal, Hahn had worked with physicists including at least one woman, Harriet Brooks

Harriet Brooks (July 2, 1876 – April 17, 1933) was the first Canadian female nuclear physicist. She is most famous for her research on nuclear transmutations and radioactivity. Ernest Rutherford, who guided her graduate work, regarded her as ...

, but it was difficult for Meitner at first. Women were not yet admitted to universities in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

. Meitner was allowed to work in the wood shop, which had its own external entrance, but could not set foot in the rest of the institute, including Hahn's laboratory space upstairs. If she wanted to go to the toilet, she had to use one at the restaurant down the street. The following year, women were admitted to universities, and Fischer lifted the restrictions, and had women's toilets installed in the building. The Institute of Physics was more accepting than chemists, and she became friends with the physicists there, including , James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate i ...

, Gustav Hertz

Gustav Ludwig Hertz (; 22 July 1887 – 30 October 1975) was a German experimental physicist and Nobel Prize winner for his work on inelastic electron collisions in gases, and a nephew of Heinrich Rudolf Hertz.

Biography

Hertz was born in Hamb ...

, Robert Pohl

Robert Wichard Pohl (10 August 1884 – 5 June 1976) was a German physicist at the University of Göttingen. Nevill Francis Mott described him as the "father of solid state physics". See also: "Components of the solid state", Nevill Mott, New Sci ...

, Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical p ...

, and Wilhelm Westphal.

Discovery of radioactive recoil

alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay, but may also be pr ...

emission and interpreted it correctly. Hahn pursued a report by Stefan Meyer and Egon Schweidler

Egon Schweidler, (* 10 February 1873, in Vienna; † 10 February 1948, in Salzburg Seeham) was an Austrian physicist.

Biography

He was born in 1873 as the son of the court and ''Gerichtsadvokaten'' Emil von Schweidler born in Vienna. After studyi ...

of a decay product of actinium with a half-life of about 11.8 days. Hahn determined that it was actinium X (radium-223

Radium-223 (223Ra, Ra-223) is an isotope of radium with an 11.4-day half-life. It was discovered in 1905 by T. Godlewski, a Polish chemist from Kraków, and was historically known as actinium X (AcX). Radium-223 dichloride is an alpha particle- ...

). Moreover, he discovered that at the moment when a radioactinium (thorium-227) atom emits an alpha particle, it does so with great force, and the actinium X experiences a recoil. This is enough to free it from chemical bonds, and it has a positive charge, and can be collected at a negative electrode. Hahn was thinking only of actinium, but on reading his paper, Meitner told him that he had found a new way of detecting radioactive substances. They set up some tests, and soon found actinium C (thallium-207) and thorium C (thallium-208). The physicist Walther Gerlach

Walther Gerlach (1 August 1889 – 10 August 1979) was a German physicist who co-discovered, through laboratory experiment, spin quantization in a magnetic field, the Stern–Gerlach effect. The experiment was conceived by Otto Stern in 1921 an ...

described radioactive recoil as "a profoundly significant discovery in physics with far-reaching consequences".

In 1910, Hahn was appointed professor by the Prussian Minister of Culture and Education, August von Trott zu Solz. Two years later, Hahn became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin-Dahlem (in what is today the Hahn-Meitner-Building of the Free University of Berlin

The Free University of Berlin (, often abbreviated as FU Berlin or simply FU) is a public research university in Berlin, Germany. It is consistently ranked among Germany's best universities, with particular strengths in political science and t ...

). This came with an annual salary of 5,000 marks. In addition, he received 66,000 marks in 1914 (of which he gave 10 per cent to Meitner) from Knöfler for the mesothorium process. The new institute was inaugurated on 23 October 1912 in a ceremony presided over by Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

. The Kaiser was shown glowing radioactive substances in a dark room.

The move to new accommodation was fortuitous, as the wood shop had become thoroughly contaminated by radioactive liquids that had been spilt, and radioactive gases that had vented and then decayed and settled as radioactive dust, making sensitive measurements impossible. To ensure that their clean new laboratories stayed that way, Hahn and Meitner instituted strict procedures. Chemical and physical measurements were conducted in different rooms, people handling radioactive substances had to follow protocols that included not shaking hands, and rolls of toilet paper were hung next to every telephone and door handle. Strongly radioactive substances were stored in the old wood shop, and later in a purpose-built radium house on the institute grounds.

Marriage to Edith Junghans

With a regular income, Hahn was now able to contemplate marriage. In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin, Hahn met (1887–1968), a student at the

With a regular income, Hahn was now able to contemplate marriage. In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin, Hahn met (1887–1968), a student at the Royal School of Art in Berlin

The Royal School of Art in Berlin (''Königliche Kunstschule zu Berlin'') was a state-sponsored art school founded in 1869. The school was founded through its association with the Prussian Academy of Arts, and after unification stood as one of Be ...

. They saw each other again in Berlin, and became engaged in November 1912. On 22 March 1913 the couple married in Edith's native city of Stettin, where her father, Paul Ferdinand Junghans, was a high-ranking law officer and President of the City Parliament until his death in 1915. After a honeymoon at Punta San Vigilio on Lake Garda

Lake Garda ( it, Lago di Garda or ; lmo, label= Eastern Lombard, Lach de Garda; vec, Ƚago de Garda; la, Benacus; grc, Βήνακος) is the largest lake in Italy.

It is a popular holiday location in northern Italy, about halfway between ...

in Italy, they visited Vienna, and then Budapest, where they stayed with George de Hevesy

George Charles de Hevesy (born György Bischitz; hu, Hevesy György Károly; german: Georg Karl von Hevesy; 1 August 1885 – 5 July 1966) was a Hungarian radiochemist and Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate, recognized in 1943 for his key rol ...

.

Their only child, , was born on 9 April 1922. During World War II, he enlisted in the army in 1942, and served with distinction on the Eastern Front as a panzer commander. He lost an arm in combat. After the war he became a distinguished art historian and architectural researcher (at the Hertziana in Rome), known for his discoveries in the early Cistercian architecture

Cistercian architecture is a style of architecture associated with the churches, monasteries and abbeys of the Roman Catholic Cistercian Order. It was heavily influenced by Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Ber ...

of the 12th century. In August 1960, while on a study trip in France, Hanno died in a car accident, together with his wife and assistant Ilse Hahn Pletz. They left a fourteen-year-old son, Dietrich Hahn.

In 1990, the for outstanding contributions to Italian art history was established in memory of Hanno and Ilse Hahn to support young and talented art historians. It is awarded biennially by the Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History

The Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History is a German research institute located in Rome, Italy. It was founded by a donation of Henriette Hertz in 1912 as a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Of the 80 institutes in the Max Planc ...

in Rome.

World War I

In July 1914—shortly before the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

—Hahn was recalled to active duty with the army in a ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortificatio ...

'' regiment. They marched through Belgium, where the platoon he commanded was armed with captured machine guns. He was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

(2nd Class) for his part in the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (french: Première Bataille des Flandres; german: Erste Flandernschlacht – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the Firs ...

. He was a joyful participant in the Christmas truce of 1914, and was commissioned as a lieutenant. In mid-January 1915, he was summoned to meet chemist Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber (; 9 December 186829 January 1934) was a German chemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method used in industry to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydroge ...

, who explained his plan to break the trench deadlock with chlorine gas

Chlorine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate betwee ...

. Hahn raised the issue that the Hague Convention banned the use of projectiles containing poison gases, but Haber explained that the French had already initiated chemical warfare with tear gas grenades, and he planned to get around the letter of the convention by releasing gas from cylinders instead of shells.

Haber's new unit was called Pioneer Regiment 35. After brief training in Berlin, Hahn, together with physicists James Franck and Gustav Hertz, was sent to Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

again to scout for a site for a first gas attack. He did not witness the attack because he and Franck were off selecting a position for the next attack. Transferred to Poland, at the Battle of Bolimów

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 12 June 1915, they released a mixture of chlorine and phosgene gas. Some German troops were reluctant to advance when the gas started to blow back, so Hahn led them across No Man's land. He witnessed the death agonies of Russians they had poisoned, and unsuccessfully attempted to revive some with gas masks. He was transferred to Berlin as a human guinea pig testing poisonous gases and gas masks. On their next attempt on 7 July, the gas again blew back on German lines, and Hertz was poisoned. This assignment was interrupted by a mission at the front in Flanders and again in 1916 by a mission to Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

to introduce shells filled with phosgene to the Western Front. Then once again he was hunting along both fronts for sites for gas attacks. In December 1916 he joined the new gas command unit at Imperial Headquarters.

Between operations, Hahn returned to Berlin, where he was able to slip back to his old laboratory and work with Meitner, continuing with their research. In September 1917 he was one of three officers, disguised in Austrian uniforms, sent to the Isonzo front

The Battles of the Isonzo (known as the Isonzo Front by historians, sl, soška fronta) were a series of 12 battles between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian armies in World War I mostly on the territory of present-day Slovenia, and the remaind ...

in Italy to find a suitable location for an attack, utilising newly developed rifled ''minenwerfer

''Minenwerfer'' ("mine launcher" or "mine thrower") is the German name for a class of short range mine shell launching mortars used extensively during the First World War by the Imperial German Army. The weapons were intended to be used by engine ...

s'' that simultaneously hurled hundreds of containers of poison gas onto enemy targets. They selected a site where the Italian trenches were sheltered in a deep valley so that a gas cloud would persist. The following Battle of Caporetto

The Battle of Caporetto (also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, the Battle of Kobarid or the Battle of Karfreit) was a battle on the Italian front of World War I.

The battle was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Central ...

broke the Italian lines, and the Central Powers overran much of northern Italy. In 1918 the German offensive in the west smashed through the Allies' lines after a massive release of gas from their mortars. That summer Hahn was accidentally poisoned by phosgene while testing a new model gas mask. At the end of the war he was in the field in mufti on a secret mission to test a pot that heated and released a cloud of arsenicals.

Discovery of protactinium

Kasimir Fajans

Kazimierz Fajans (Kasimir Fajans in many American publications; 27 May 1887 – 18 May 1975) was a Polish American physical chemist of Polish-Jewish origin, a pioneer in the science of radioactivity and the discoverer of chemical element protact ...

independently observed that alpha decay

Alpha decay or α-decay is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits an alpha particle (helium nucleus) and thereby transforms or 'decays' into a different atomic nucleus, with a mass number that is reduced by four and an at ...

caused atoms to shift down two places on the periodic table, while the loss of two beta particles restored it to its original position. Under the resulting reorganisation of the periodic table, radium was placed in group II, actinium

Actinium is a chemical element with the symbol Ac and atomic number 89. It was first isolated by Friedrich Oskar Giesel in 1902, who gave it the name ''emanium''; the element got its name by being wrongly identified with a substance An ...

in group III, thorium in group IV and uranium in group VI. This left a gap between thorium and uranium. Soddy predicted that this unknown element, which he referred to (after Dmitri Mendeleev) as "ekatantalium", would be an alpha emitter with chemical properties similar to tantalium. It was not long before Fajans and Oswald Helmuth Göhring

Oswald Helmuth Göhring, also known as Otto Göhring, (1889 - 1915) was a German chemist who, with his teacher Kasimir Fajans, co-discovered the chemical element protactinium in 1913.

Discovery of protactinium

Protactinium was first identified ...

discovered it as a decay product of a beta-emitting product of thorium. Based on the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy, this was an isotope of the missing element, which they named "brevium" after its short half life. However, it was a beta emitter, and therefore could not be the mother isotope of actinium. This had to be another isotope of the same element.

Hahn and Meitner set out to find the missing mother isotope. They developed a new technique for separating the tantalum group from pitchblende, which they hoped would speed the isolation of the new isotope. The work was interrupted by the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Meitner became an X-ray nurse, working in Austrian Army hospitals, but she returned to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in October 1916. Hahn joined the new gas command unit at Imperial Headquarters in Berlin in December 1916 after travelling between the western and eastern front, Berlin and Leverkusen between the summer of 1914 and late 1916.

Most of the students, laboratory assistants and technicians had been called up, so Hahn and Meitner had to do everything themselves. By December 1917 they was able to isolate 231Pa, and after further work were able to prove that it was indeed the missing isotope. Meitner submitted their findings in both their names for publication in March 1918 to the scientific paper '' Physikalischen Zeitschrift'' under the title .

Although Fajans and Göhring had been the first to discover the element, custom required that an element was represented by its longest-lived and most abundant isotope, and brevium did not seem appropriate. Fajans agreed to Meitner and Hahn naming the element protoactinmium, and assigning it the chemical symbol Pa. In June 1918, Soddy and John Cranston announced that they had extracted a sample of the isotope, but unlike Hahn and Meitner were unable to describe its characteristics. They acknowledged Hahn´s and Meitner's priority, and agreed to the name. The connection to uranium remained a mystery, as neither of the known isotopes of uranium

Uranium (92U) is a naturally occurring radioactive element that has no stable isotope. It has two primordial isotopes, uranium-238 and uranium-235, that have long half-lives and are found in appreciable quantity in the Earth's crust. The d ...

decayed into protactinium. It remained unsolved until the mother isotope, uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

, was discovered in 1929.

For their discovery Hahn and Meitner were repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in the 1920s by several scientists, among them Max Planck, Heinrich Goldschmidt, and Fajans himself. In 1949, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC ) is an international federation of National Adhering Organizations working for the advancement of the chemical sciences, especially by developing nomenclature and terminology. It is ...

) named the new element definitively protactinium, and confirmed Hahn and Meitner as discoverers.

Discovery of nuclear isomerism

uranyl nitrate

Uranyl nitrate is a water-soluble yellow uranium salt with the formula . The hexa-, tri-, and dihydrates are known. The compound is mainly of interest because it is an intermediate in the preparation of nuclear fuels.

Uranyl nitrate can be prepa ...

remained constant over time, strongly indicating that uranium X was the mother of uranium Z. To prove this, Hahn obtained a hundred kilograms of uranyl nitrate; separating the uranium X from it took weeks. He found that the half life of the parent of uranium Z differed from the known 24 day half life of uranium X1 by no more than two or three days, but was unable to get a more accurate value. Hahn concluded that uranium Z and uranium X2 were both the same isotope of protactinium (protactinium-234

Protactinium (91Pa) has no stable isotopes. The three naturally occurring isotopes allow a standard atomic weight to be given.

Thirty radioisotopes of protactinium have been characterized, with the most stable being 231Pa with a half-life of 32, ...

), and they both decayed into uranium II (uranium-234), but with different half lives.

Uranium Z was the first example of nuclear isomer

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy higher energy levels than in the ground state of the same nucleus. "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have ...

ism. Walther Gerlach later remarked that this was "a discovery that was not understood at the time but later became highly significant for nuclear physics". Not until 1936 was Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker

Carl Friedrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (; 28 June 1912 – 28 April 2007) was a German physicist and philosopher. He was the longest-living member of the team which performed nuclear research in Germany during the Second World War, under ...

able to provide a theoretical explanation of the phenomenon. For this discovery, whose full significance was recognised by very few, Hahn was again proposed for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry by Bernhard Naunyn, Goldschmidt and Planck.

''Applied Radiochemistry''

In 1924, Hahn was elected to full membership of thePrussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

in Berlin, by a vote of thirty white balls to two black. While still remaining the head of his own department, he hecame Deputy Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in 1924, and succeeded Alfred Stock as the director in 1928. Meitner became the director of the Physical Radioactivity Division, while Hahn headed the Chemical Radioactivity Division. In the early 1920s, he created a new line of research. Using the "emanation method", which he had recently developed, and the "emanation ability", he founded what became known as "applied radiochemistry" for the researching of general chemical and physical-chemical questions. In 1936 Cornell University Press published a book in English (and later in Russian) titled '' Applied Radiochemistry'', which contained the lectures given by Hahn when he was a visiting professor at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

in Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named ...

, in 1933. This important publication had a major influence on almost all nuclear chemists and physicists in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union during the 1930s and 1940s.

In 1966, Glenn T. Seaborg

Glenn Theodore Seaborg (; April 19, 1912February 25, 1999) was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work i ...

, co-discoverer of many transuranium elements, wrote about this book as follows:

Hahn is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry, which emerged from applied radichemistry.

National socialism

Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

had come to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry to study under Hahn to improve his employment prospects. After the Nazi Party