Historians who debate the origins of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

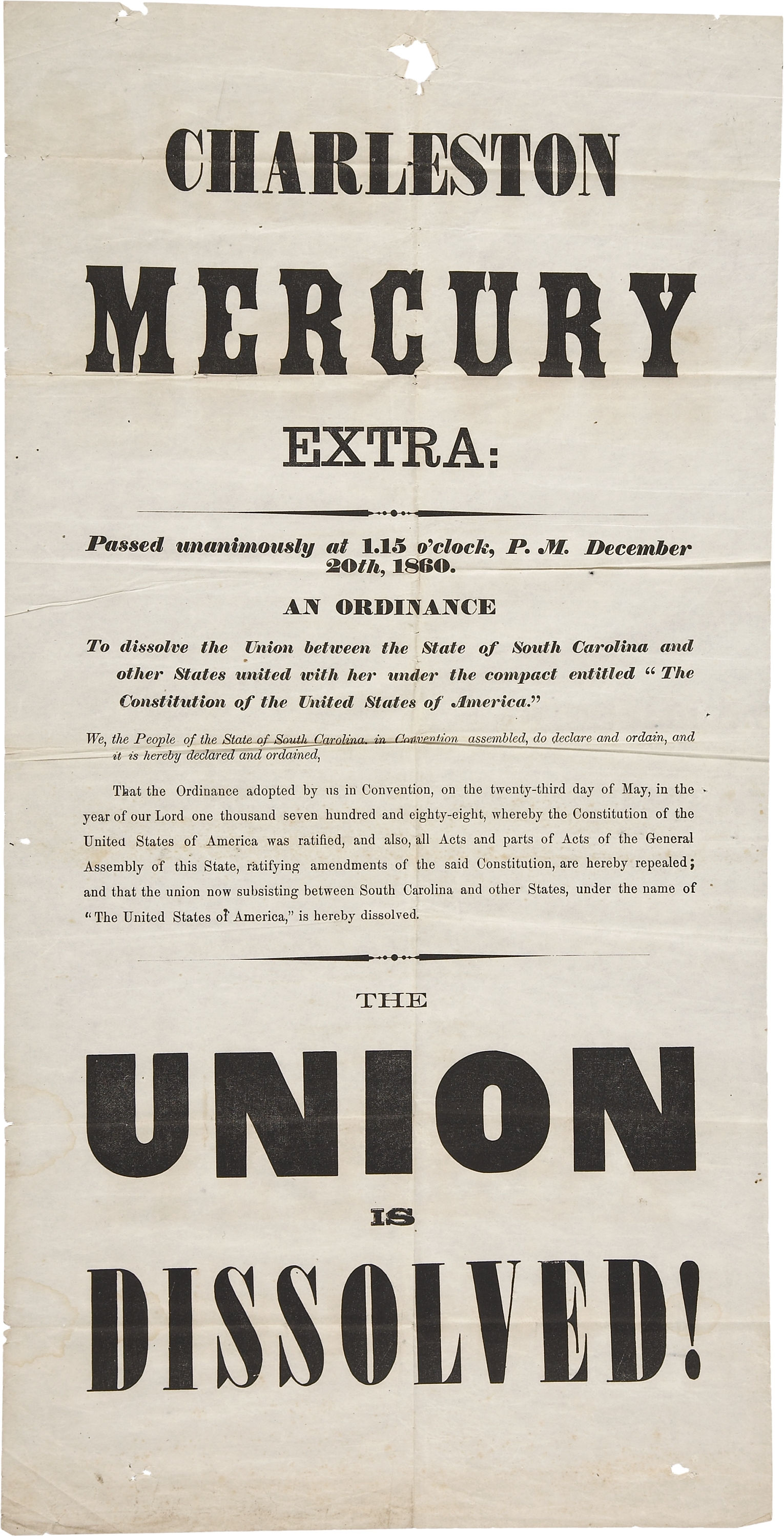

focus on the reasons that seven

Southern states (followed by four other states after the onset of the war) declared their secession from the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

(the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

) and united to form the

Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

(known as the "Confederacy"), and the reasons that the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

refused to let them go. Proponents of the

pseudo-historical

Pseudohistory is a form of pseudoscholarship that attempts to distort or misrepresent the historical record, often by employing methods resembling those used in scholarly historical research. The related term cryptohistory is applied to pseudohi ...

Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

ideology have denied that

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was the principal cause of the secession. While historians in the 21st century

agree on the centrality of the conflict over slavery—it was not just "a cause" of the war but "the cause"—they disagree sharply on which aspects of this conflict (ideological, economic, political, or social) were most important.

The principal political battle leading to Southern secession was over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into newly acquired Western territories destined to become states. Initially

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

had admitted new states into the Union in pairs,

one slave and one free. This had kept a sectional balance in the

Senate but not in the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

, as free states outstripped slave states in population.

Thus, at mid-19th century, the free-versus-slave status of the new territories was a critical issue, both for the North, where anti-slavery sentiment had grown, and for the South, where the fear of slavery's abolition had grown. Another factor leading to secession and the formation of the Confederacy was the development of

white Southern nationalism in the preceding decades. The primary reason for the North to reject secession was to preserve the Union, a cause based on

American nationalism

American nationalism, is a form of civic, ethnic, cultural or economic influences

*

*

*

*

*

*

* found in the United States. Essentially, it indicates the aspects that characterize and distinguish the United States as an autonomous political ...

.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

won the

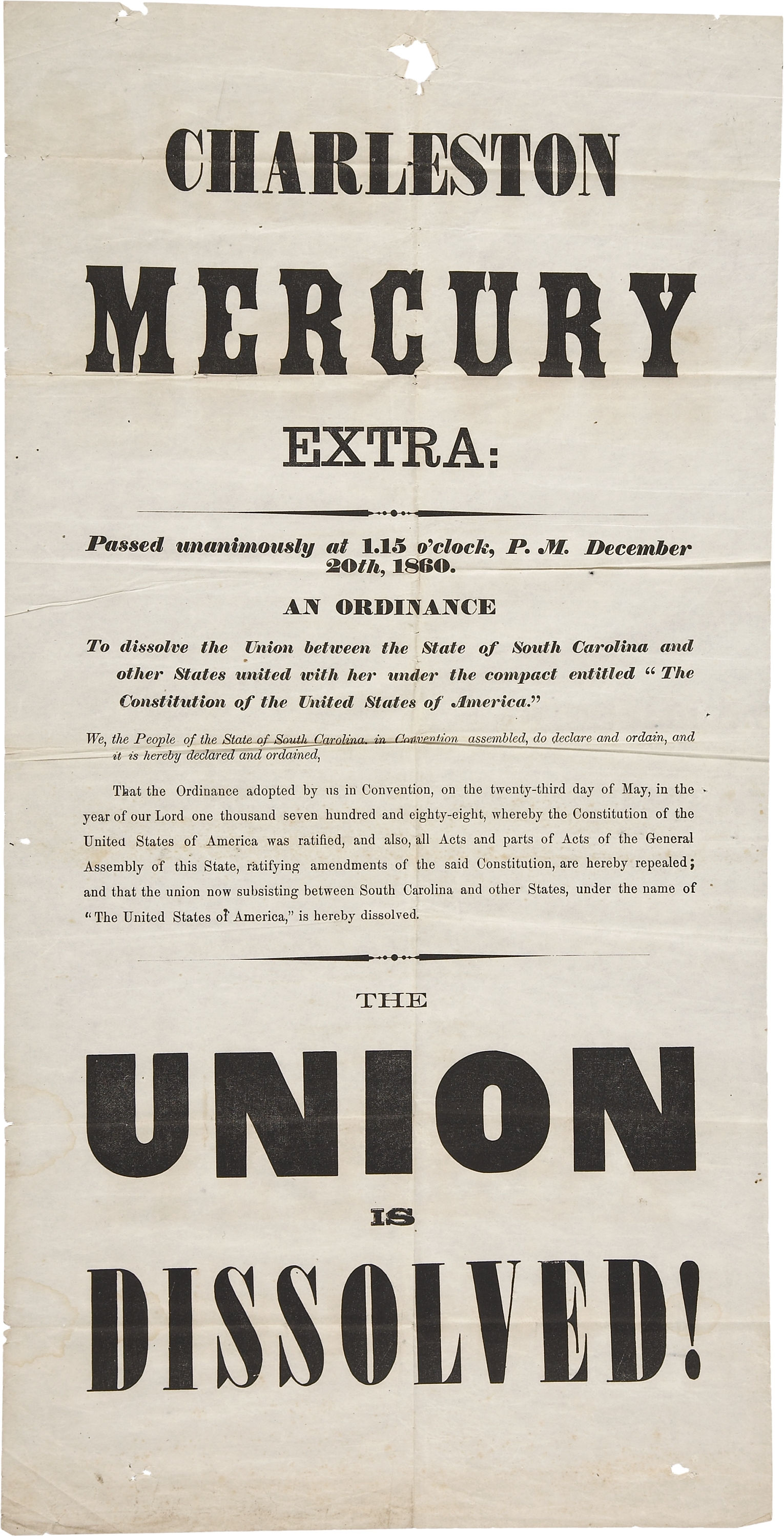

1860 presidential election, even though he was not on the ballot in ten Southern states. His victory triggered declarations of

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

by seven slave states of the

Deep South, all of whose riverfront or coastal economies were based on cotton that was cultivated by enslaved labor. They formed the Confederate States after Lincoln was elected in November 1860 but before

he took office in March 1861.

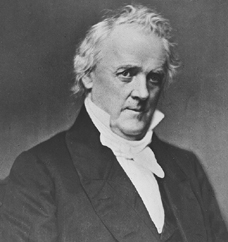

Nationalists in the North and "Unionists" in the South refused to accept the declarations of secession. No foreign government ever recognized the Confederacy. The U.S. government, under President

James Buchanan, refused to relinquish its forts that were in territory claimed by the Confederacy. The war itself began on April 12, 1861, when

Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter, in the harbor of

Charleston, South Carolina.

As a panel of historians emphasized in 2011, "while slavery and its various and multifaceted discontents were the primary cause of disunion, it was disunion itself that sparked the war." Historian

David M. Potter wrote: "The problem for Americans who, in the age of Lincoln, wanted slaves to be free was not simply that southerners wanted the opposite, but that they themselves cherished a conflicting value: they wanted the Constitution, which protected slavery, to be honored, and the Union, which had fellowship with slaveholders, to be preserved. Thus they were committed to values that could not logically be reconciled."

Other important factors were

partisan politics

A partisan is a committed member of a political party or army. In multi-party systems, the term is used for persons who strongly support their party's policies and are reluctant to compromise with political opponents. A political partisan is no ...

,

abolitionism,

nullification

Nullification may refer to:

* Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution

* Nullification Crisis, the 1832 confront ...

versus

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

, Southern and Northern nationalism,

expansionism,

economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

, and modernization in the

Antebellum period

In the history of the Southern United States, the Antebellum Period (from la, ante bellum, lit= before the war) spanned the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. The Antebellum South was characterized by ...

.

Geography and demographics

By the mid-19th century the United States had become a nation of two distinct regions. The

free states in

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, the

Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

, and the

Midwest had a rapidly growing economy based on family farms, industry, mining, commerce and transportation, with a large and rapidly growing urban population. Their growth was fed by a high birth rate and large numbers of European immigrants, especially from

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. The South was dominated by a settled

plantation system

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash ...

based on slavery; there was some rapid growth taking place in the Southwest (e.g.,

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

), based on high birth rates and high migration from the Southeast; there was also immigration by Europeans, but in much smaller number. The heavily rural South had few cities of any size, and little manufacturing except in border areas such as

St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

and

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. Slave owners controlled politics and the economy, although about 75% of white Southern families owned no slaves.

Overall, the Northern population was growing much more quickly than the Southern population, which made it increasingly difficult for the South to dominate the national government. By the time the 1860 election occurred, the heavily agricultural Southern states as a group had fewer

Electoral College votes than the rapidly

industrializing

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

Northern states. Abraham Lincoln was able to win the

1860 presidential election without even being on the ballot in ten Southern states. Southerners felt a loss of federal concern for Southern pro-slavery political demands, and their continued domination of the federal government was threatened. This political calculus provided a very real basis for Southerners' worry about the relative political decline of their region, due to the North growing much faster in terms of population and industrial output.

In the interest of maintaining unity, politicians had mostly moderated opposition to slavery, resulting in numerous compromises such as the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

of 1820 under the presidency of

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. After the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

of 1846 to 1848, the issue of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the new

territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

led to the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

. While the compromise averted an immediate political crisis, it did not permanently resolve the issue of the

Slave Power (the power of slaveholders to control the national government on the slavery issue). Part of the Compromise of 1850 was the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most con ...

that required Northerners assist Southerners in reclaiming fugitive slaves, which many Northerners found to be extremely offensive.

Amid the emergence of increasingly virulent and hostile sectional ideologies in national politics, the collapse of the old

Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

in the 1850s hampered politicians' efforts to reach yet another compromise. The compromise that was reached (the 1854

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

) outraged many Northerners and led to the formation of the

Republican Party, the first major party that was almost entirely Northern-based. The industrializing North and agrarian Midwest became committed to the economic ethos of free-labor

industrial capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

.

Arguments that slavery was undesirable for the nation had long existed, and early in U.S. history were made even by some prominent Southerners. After 1840, abolitionists denounced slavery as not only a social evil but also a moral wrong. Activists in the new Republican Party, usually Northerners, had another view: They believed the Slave Power conspiracy was controlling the national government with the goal of extending slavery and limiting access to good farm land to rich slave owners.

[Leonard L. Richards, ''The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780–1860'' (2000).] Southern defenders of slavery, for their part, increasingly came to contend that black people benefited from slavery.

Historical tensions and compromises

Early Republic

At the time of the American Revolution, the institution of slavery was firmly established in the American colonies. It was most important in the six southern states from Maryland to Georgia, but the total of a half million slaves were spread out through all of the colonies. In the South, 40% of the population was made up of slaves, and as Americans moved into Kentucky and the rest of the southwest, one-sixth of the settlers were slaves. By the end of the Revolutionary War, the

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

states provided most of the American ships that were used in the foreign slave trade, while most of their customers were in Georgia and

the Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nor ...

.

During this time many Americans found it easy to reconcile slavery with the Bible but a growing number rejected this defense of slavery. A small antislavery movement, led by the

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, appeared in the 1780s, and by the late 1780s all of the states banned the international slave trade. No serious national political movement against slavery developed, largely due to the overriding concern over achieving national unity. When the Constitutional Convention met, slavery was the one issue "that left the least possibility of compromise, the one that would most pit morality against pragmatism." In the end, many would take comfort in the fact that the word "slavery" never occurs in the Constitution. The

three-fifths clause was a compromise between those (in the North) who wanted no slaves counted, and those (in the South) who wanted all the slaves counted. The Constitution also allowed the federal government to suppress domestic violence which would dedicate national resources to defending against slave revolts. Imports could not be banned for 20 years. The need for three-fourths approval for amendments made the constitutional abolition of slavery virtually impossible.

With the

outlawing of the African slave trade on January 1, 1808, many Americans felt that the slavery issue was resolved. Any national discussion that might have continued over slavery was drowned out by the years of trade embargoes, maritime competition with Great Britain and France, and, finally, the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. The one exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.

During and in the aftermath of the American Revolution (1775–1783), the Northern states (north of the

Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virginia ...

separating Pennsylvania from Maryland and Delaware) abolished slavery by 1804, although in some states older slaves were turned into indentured servants who could not be bought or sold. In the

Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Congress (still under the

Articles of Confederation) barred slavery from the Midwestern territory north of the

Ohio River. When Congress organized the territories acquired through the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

of 1803, there was no ban on slavery.

Missouri Compromise

In 1819 Congressman

James Tallmadge Jr. of New York initiated an uproar in the South when he proposed two amendments to a bill admitting

Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

to the Union as a free state. The first would have barred slaves from being moved to Missouri, and the second would have freed all Missouri slaves born after admission to the Union at age 25. With the admission of Alabama as a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

in 1819, the U.S. was equally divided with 11 slave states and 11 free states. The admission of the new state of Missouri as a slave state would give the slave states a majority in the Senate; the

Tallmadge Amendment would give the free states a majority.

The Tallmadge amendments passed the House of Representatives but failed in the Senate when five Northern senators voted with all the Southern senators. The question was now the admission of Missouri as a slave state, and many leaders shared

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

's fear of a crisis over slavery—a fear that Jefferson described as "a fire bell in the night". The crisis was solved by the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

, in which

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

agreed to cede control over its relatively large, sparsely populated and disputed

exclave, the

District of Maine

The District of Maine was the governmental designation for what is now the U.S. state of Maine from October 25, 1780 to March 15, 1820, when it was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state. The district was a part of the Commonwealth of Massachu ...

. The compromise allowed

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

to be admitted to the Union as a free state at the same time that Missouri was admitted as a slave state. The Compromise also banned slavery in the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

territory north and west of the state of Missouri along the line of 36–30. The Missouri Compromise quieted the issue until its limitations on slavery were repealed by the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

of 1854.

In the South, the Missouri crisis reawakened old fears that a strong federal government could be a fatal threat to slavery. The

Jeffersonian coalition that united southern planters and northern farmers, mechanics and artisans in opposition to the threat presented by the

Federalist Party had started to dissolve after the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. It was not until the Missouri crisis that Americans became aware of the political possibilities of a sectional attack on slavery, and it was not until the

mass politics

Mass politics is a political order resting on the emergence of mass political parties.

The emergence of mass politics generally associated with the rise of mass society coinciding with the Industrial Revolution in the West. However, because of ...

of

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's administration that this type of organization around this issue became practical.

Nullification crisis

The

American System, advocated by

Henry Clay in Congress and supported by many nationalist supporters of the War of 1812 such as

John C. Calhoun, was a program for rapid economic modernization featuring protective tariffs,

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

at federal expense, and a national bank. The purpose was to develop American industry and international commerce. Since iron, coal, and water power were mainly in the North, this tax plan was doomed to cause rancor in the South, where economies were agriculture-based. Southerners claimed it demonstrated favoritism toward the North.

The nation suffered an economic downturn throughout the 1820s, and South Carolina was particularly affected. The highly protective Tariff of 1828 (called the "

Tariff of Abominations

The Tariff of 1828 was a very high protective tariff that became law in the United States in May 1828. It was a bill designed to not pass Congress because it was seen by free trade supporters as hurting both industry and farming, but surprising ...

" by its detractors), designed to protect American industry by taxing imported manufactured goods, was enacted into law during the last year of the presidency of

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

. Opposed in the South and parts of New England, the expectation of the tariff's opponents was that with the election of

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

the tariff would be significantly reduced.

By 1828 South Carolina state politics increasingly organized around the tariff issue. When the Jackson administration failed to take any actions to address their concerns, the most radical faction in the state began to advocate that the state declare the tariff null and void within South Carolina. In Washington, an open split on the issue occurred between Jackson and his vice-president John C. Calhoun, the most effective proponent of the constitutional theory of state nullification through his 1828 "

South Carolina Exposition and Protest

The South Carolina Exposition and Protest, also known as Calhoun's Exposition, was written in December 1828 by John C. Calhoun, then Vice President of the United States under John Quincy Adams and later under Andrew Jackson. Calhoun did not formall ...

".

Congress enacted a new

tariff in 1832, but it offered the state little relief, resulting in the most dangerous sectional crisis since the Union was formed. Some militant South Carolinians even hinted at withdrawing from the Union in response. The newly elected South Carolina legislature then quickly called for the election of delegates to a state convention. Once assembled, the convention voted to declare null and void the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 within the state. President Andrew Jackson responded firmly, declaring nullification an act of

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. He then took steps to strengthen federal forts in the state.

Violence seemed a real possibility early in 1833 as Jacksonians in Congress introduced a "

Force Bill

The Force Bill, formally titled "''An Act further to provide for the collection of duties on imports''", (1833), refers to legislation enacted by the 22nd U.S. Congress on March 2, 1833, during the nullification crisis.

Passed by Congress at ...

" authorizing the President to use the federal army and navy in order to enforce acts of Congress. No other state had come forward to support South Carolina, and the state itself was divided on willingness to continue the showdown with the federal government. The crisis ended when Clay and Calhoun worked to devise a compromise tariff. Both sides later claimed victory. Calhoun and his supporters in South Carolina claimed a victory for nullification, insisting that it had forced the revision of the tariff. Jackson's followers, however, saw the episode as a demonstration that no single state could assert its rights by independent action.

Calhoun, in turn, devoted his efforts to building up a sense of Southern solidarity so that when another standoff should come, the whole section might be prepared to act as a bloc in resisting the federal government. As early as 1830, in the midst of the crisis, Calhoun identified the right to own slaves—the foundation of the plantation agricultural system—as the chief southern minority right being threatened:

On May 1, 1833, Jackson wrote of this idea, "the tariff was only the pretext, and

disunion and

southern confederacy

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

question."

The issue appeared again after 1842's

Black Tariff. A period of relative free trade followed 1846's

Walker Tariff

The Walker Tariff was a set of tariff rates adopted by the United States in 1846. Enacted by the Democrats, it made substantial cuts in the high rates of the " Black Tariff" of 1842, enacted by the Whigs. It was based on a report by Secretary of ...

, which had been largely written by Southerners. Northern industrialists (and some in western Virginia) complained it was too low to encourage the growth of industry.

Gag Rule debates

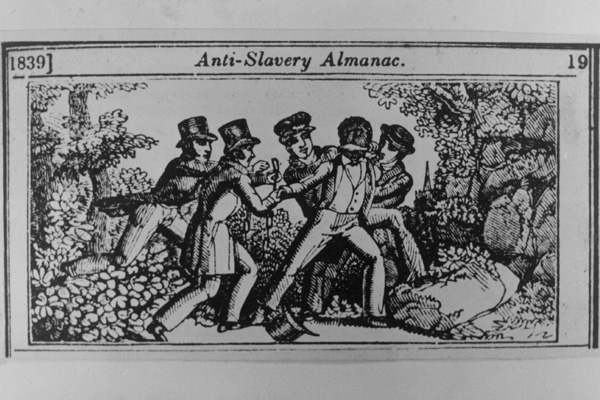

From 1831 to 1836

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

and the

American Anti-Slavery Society (AA-SS) initiated a campaign to petition Congress in favor of ending

slavery in the District of Columbia

The slave trade in the District of Columbia was legal from its creation until 1850, when the trade in enslaved people in the District was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming ...

and all federal territories. Hundreds of thousands of petitions were sent, with the number reaching a peak in 1835.

The

House passed the Pinckney Resolutions on May 26, 1836. The first of these stated that Congress had no constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the states and the second that it "ought not" do so in the District of Columbia. The third resolution, known from the beginning as the "gag rule", provided that:

The first two resolutions passed by votes of 182 to 9 and 132 to 45. The gag rule, supported by Northern and Southern Democrats as well as some Southern Whigs, was passed with a vote of 117 to 68.

Former President

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, who was elected to the House of Representatives in 1830, became an early and central figure in the opposition to the gag rules. He argued that they were a direct violation of the

First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

right "to petition the Government for a redress of grievances". A majority of Northern

Whigs joined the opposition. Rather than suppress anti-slavery petitions, however, the gag rules only served to offend Americans from Northern states, and dramatically increase the number of petitions.

Since the original gag was a resolution, not a standing House Rule, it had to be renewed every session, and the Adams' faction often gained the floor before the gag could be imposed. However, in January 1840, the House of Representatives passed the Twenty-first Rule, which prohibited even the reception of anti-slavery petitions and was a standing House rule. Now the pro-petition forces focused on trying to revoke a standing rule. The Rule raised serious doubts about its constitutionality and had less support than the original Pinckney gag, passing only by 114 to 108. Throughout the gag period, Adams' "superior talent in using and abusing parliamentary rules" and skill in baiting his enemies into making mistakes, enabled him to evade the rule and debate the slavery issues. The gag rule was finally rescinded on December 3, 1844, by a strongly sectional vote of 108 to 80, all the Northern and four Southern Whigs voting for repeal, along with 55 of the 71 Northern Democrats.

Antebellum South and the Union

There had been a continuing contest between the states and the national government over the power of the latter—and over the loyalty of the citizenry—almost since the founding of the republic. The

Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued ...

of 1798, for example, had defied the

Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

, and at the

Hartford Convention

The Hartford Convention was a series of meetings from December 15, 1814, to January 5, 1815, in Hartford, Connecticut, United States, in which the New England Federalist Party met to discuss their grievances concerning the ongoing War of 1812 and ...

,

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

voiced its opposition to President

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

and the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, and discussed secession from the Union.

Southern culture

Although a minority of free Southerners owned slaves, free Southerners of all classes nevertheless defended the institution of slavery—threatened by the rise of free labor abolitionist movements in the Northern states—as the cornerstone of their social order.

Per the 1860 census, the percentage of slaveholding families was as follows:

* 26% in the 15 Slave states (AL, AR, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, MO, NC, SC, TN, TX, VA)

* 16% in the 4 Border states (DE, KY, MD, MO)

* 31% in the 11 Confederate states (AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, TX, VA)

* 37% in the first 7 Confederate states (AL, FL, GA, LA, MS, SC, TX)

* 25% in the second 4 Confederate states (AR, NC, TN, VA)

Mississippi was the highest at 49%, followed by South Carolina at 46%

Based on a system of

plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

slavery, the social structure of the South was far more stratified and patriarchal than that of the North. In 1850 there were around 350,000 slaveholders in a total free Southern population of about six million. Among slaveholders, the concentration of slave ownership was unevenly distributed. Perhaps around 7 percent of slaveholders owned roughly three-quarters of the slave population. The largest slaveholders, generally owners of large plantations, represented the top stratum of Southern society. They benefited from

economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables ...

and needed large numbers of slaves on big plantations to produce cotton, a highly profitable labor-intensive crop.

Per the 1860 Census, in the 15 slave states, slaveholders owning 30 or more slaves (7% of all slaveholders) owned approximately 1,540,000 slaves (39% of all slaves).(PDF p. 64/1860 Census p. 247)

In the 1850s, as large plantation owners outcompeted smaller farmers, more slaves were owned by fewer planters. Yet poor whites and small farmers generally accepted the political leadership of the planter elite. Several factors helped explain why slavery was not under serious threat of internal collapse from any move for democratic change initiated from the South. First, given the opening of new territories in the West for white settlement, many non-slaveowners also perceived a possibility that they, too, might own slaves at some point in their life.

Second, small free farmers in the South often embraced

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

, making them unlikely agents for internal democratic reforms in the South.

The principle of

white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

, accepted by almost all white Southerners of all classes, made slavery seem legitimate, natural, and essential for a civilized society. "Racial" discrimination was completely legal. White racism in the South was sustained by official systems of repression such as the "slave codes" and elaborate codes of speech, behavior, and social practices illustrating the subordination of blacks to whites. For example, the "

slave patrol

Slave patrols—also known as patrollers, patterrollers, pattyrollers or paddy rollersVerner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis (2019). ''Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement''. p. 323. Rowman & Littlefield—were organized groups of armed men who m ...

s" were among the institutions bringing together southern whites of all classes in support of the prevailing economic and racial order. Serving as slave "patrollers" and "overseers" offered white Southerners positions of power and honor in their communities. Policing and punishing Blacks who transgressed the regimentation of slave society was a valued community service in the South, where the fear of free Blacks threatening law and order figured heavily in the public discourse of the period.

Third, many

yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

and small farmers with a few slaves were linked to elite planters through the market economy.

In many areas, small farmers depended on local planter elites for vital goods and services, including access to

cotton gins, markets, feed and livestock, and even loans (since the banking system was not well developed in the antebellum South). Southern tradesmen often depended on the richest planters for steady work. Such dependency effectively deterred many white non-slaveholders from engaging in any political activity that was not in the interest of the large slaveholders. Furthermore, whites of varying social class, including poor whites and "plain folk" who worked outside or in the periphery of the market economy (and therefore lacked any real economic interest in the defense of slavery) might nonetheless be linked to elite planters through extensive kinship networks. Since

inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officia ...

in the South was often unequitable (and generally favored eldest sons), it was not uncommon for a poor white person to be perhaps the first cousin of the richest plantation owner of his county and to share the same militant support of slavery as his richer relatives. Finally, there was no

secret ballot at the time anywhere in the United States—this innovation did not become widespread in the U.S. until the 1880s. For a typical white Southerner, this meant that so much as casting a ballot against the wishes of the establishment meant running the risk of being socially

ostracized.

Thus, by the 1850s, Southern slaveholders and non-slaveholders alike felt increasingly encircled psychologically and politically in the national political arena because of the rise of

free soilism and

abolitionism in the Northern states. Increasingly dependent on the North for manufactured goods, for commercial services, and for loans, and increasingly cut off from the flourishing agricultural regions of the Northwest, they faced the prospects of a growing free labor and abolitionist movement in the North.

Historian

William C. Davis refutes the argument that Southern culture was different from that of Northern states or that it was a cause of the war, stating, "Socially and culturally the North and South were not much different. They prayed to the same deity, spoke the same language, shared the same ancestry, sang the same songs. National triumphs and catastrophes were shared by both." He stated that culture was not the cause of the war, but rather, slavery was: "For all the myths they would create to the contrary, the only significant and defining difference between them was slavery, where it existed and where it did not, for by 1804 it had virtually ceased to exist north of Maryland. Slavery demarked not just their labor and economic situations, but power itself in the new republic."

Militant defense of slavery

With the outcry over developments in Kansas strong in the North, defenders of slavery—increasingly committed to a way of life that abolitionists and their sympathizers considered obsolete or immoral—articulated a militant pro-slavery ideology that would lay the groundwork for secession upon the election of a Republican president. Southerners waged a vitriolic response to political change in the North. Slaveholding interests sought to uphold their constitutional rights in the territories and to maintain sufficient political strength to repulse "hostile" and "ruinous" legislation. Behind this shift was the growth of the cotton textile industry in the North and in Europe, which left slavery more important than ever to the Southern economy.

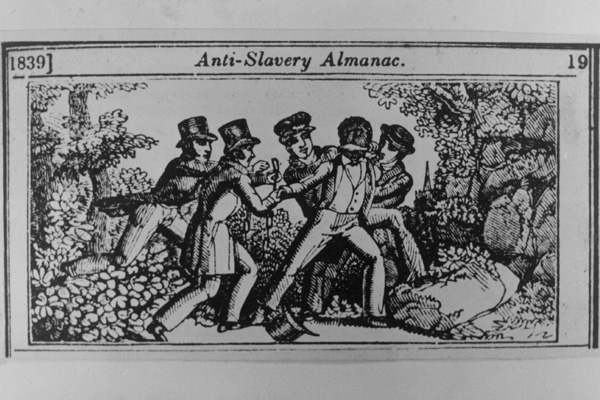

Abolitionism

Southern spokesmen greatly exaggerated the power of abolitionists, looking especially at the great popularity of ''

Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' (1852), the novel and play by

Harriet Beecher Stowe (whom Abraham Lincoln reputedly called "the little woman that started this great war"). They saw a vast growing abolitionist movement after the success of ''

The Liberator'' in 1831 by

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

. The fear was a

race war

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positio ...

by blacks that would massacre whites, especially in counties where whites were a small minority.

The South reacted with an elaborate intellectual defense of slavery.

J. D. B. De Bow of New Orleans established ''

De Bow's Review'' in 1846, which quickly grew to become the leading Southern magazine, warning about the dangers of depending on the North economically. ''De Bow's Review'' also emerged as the leading voice for secession. The magazine emphasized the South's economic inequality, relating it to the concentration of manufacturing, shipping, banking and international trade in the North. Searching for Biblical passages endorsing slavery and forming economic, sociological, historical and scientific arguments, slavery went from being a "necessary evil" to a "positive good". Dr.

John H. Van Evrie's book ''Negroes and Negro slavery: The First an Inferior Race: The Latter Its Normal Condition''—setting out the arguments the title would suggest—was an attempt to apply scientific support to the Southern arguments in favor of race-based slavery.

Latent sectional divisions suddenly activated derogatory sectional imagery which emerged into sectional ideologies. As industrial capitalism gained momentum in the North, Southern writers emphasized whatever aristocratic traits they valued (but often did not practice) in their own society: courtesy, grace,

chivalry, the slow pace of life, orderly life and leisure. This supported their argument that slavery provided a more humane society than industrial labor. In his ''Cannibals All!'',

George Fitzhugh

George Fitzhugh (November 4, 1806 – July 30, 1881) was an American social theorist who published racial and slavery-based sociological theories in the antebellum era. He argued that the negro was "but a grown up child" needing the economic and ...

argued that the antagonism between labor and capital in a free society would result in "

robber barons" and "pauper slavery", while in a slave society such antagonisms were avoided. He advocated enslaving Northern factory workers, for their own benefit. Abraham Lincoln, on the other hand, denounced such Southern insinuations that Northern wage earners were fatally fixed in that condition for life. To Free Soilers, the stereotype of the South was one of a diametrically opposite, static society in which the slave system maintained an entrenched anti-democratic aristocracy.

Southern fears of modernization

According to the historian

James M. McPherson

James Munro McPherson (born October 11, 1936) is an American Civil War historian, and is the George Henry Davis '86 Professor Emeritus of United States History at Princeton University. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for '' Battle Cry of ...

, exceptionalism applied not to the South but to the North after the North ended slavery and launched an industrial revolution that led to urbanization, which in turn led to increased education, which in its own turn gave ever-increasing strength to various reform movements but especially abolitionism. The fact that seven immigrants out of eight settled in the North (and the fact that most immigrants viewed slavery with disfavor), compounded by the fact that twice as many whites left the South for the North as vice versa, contributed to the South's defensive-aggressive political behavior. The ''

Charleston Mercury'' wrote that on the issue of slavery the North and South "are not only two Peoples, but they are rival, hostile Peoples."

James M. McPherson

James Munro McPherson (born October 11, 1936) is an American Civil War historian, and is the George Henry Davis '86 Professor Emeritus of United States History at Princeton University. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for '' Battle Cry of ...

, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question", ''Civil War History'' 29 (September 1983) As ''De Bow's Review'' said, "We are resisting revolution. ... We are not engaged in a Quixotic fight for the rights of man. ... We are conservative."

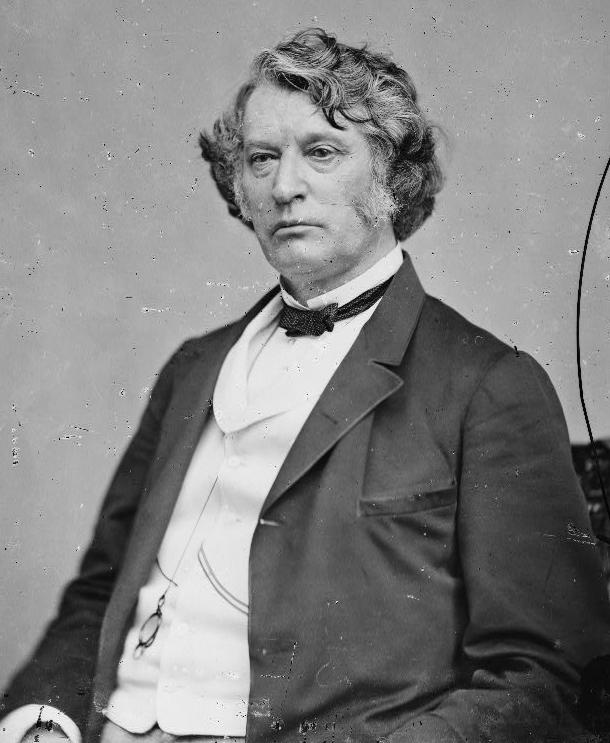

Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

argued that the Civil War was an "irrepressible" conflict, adopting a phrase from Senator

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

. Nevins synthesized contending accounts emphasizing moral, cultural, social, ideological, political, and economic issues. In doing so, he brought the historical discussion back to an emphasis on social and cultural factors. Nevins pointed out that the North and the South were rapidly becoming two different peoples, a point made also by historian

Avery Craven

Avery Odelle Craven (August 12, 1885 – January 21, 1980) was an American historian who wrote extensively about the nineteenth-century United States, the American Civil War and Congressional Reconstruction from a then-revisionist viewpoint sym ...

. At the root of these cultural differences was the problem of slavery, but fundamental assumptions, tastes, and cultural aims of the regions were diverging in other ways as well. More specifically, the North was rapidly modernizing in a manner threatening to the South. Historian McPherson explains:

When secessionists protested in 1861 that they were acting to preserve traditional rights and values, they were correct. They fought to preserve their constitutional liberties against the perceived Northern threat to overthrow them. The South's concept of republicanism had not changed in three-quarters of a century; the North's had. ... The ascension to power of the Republican Party, with its ideology of competitive, egalitarian free-labor capitalism, was a signal to the South that the Northern majority had turned irrevocably towards this frightening, revolutionary future.

Harry L. Watson has synthesized research on antebellum southern social, economic, and political history. Self-sufficient

yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, in Watson's view, "collaborated in their own transformation" by allowing promoters of a market economy to gain political influence. Resultant "doubts and frustrations" provided fertile soil for the argument that southern rights and liberties were menaced by Black Republicanism.

J. Mills Thornton III explained the viewpoint of the average white Alabamian. Thornton contends that Alabama was engulfed in a severe crisis long before 1860. Deeply held principles of freedom, equality, and autonomy, as expressed in

Republican values, appeared threatened, especially during the 1850s, by the relentless expansion of market relations and commercial agriculture. Alabamians were thus, he judged, prepared to believe the worst once Lincoln was elected.

Sectional tensions and the emergence of mass politics

The politicians of the 1850s were acting in a society in which the traditional restraints that suppressed sectional conflict in the 1820s and 1850s—the most important of which being the stability of the two-party system—were being eroded as this rapid extension of democracy went forward in the North and South. It was an era when the mass political party galvanized voter participation to 80% or 90% turnout rates, and a time in which politics formed an essential component of American mass culture. Historians agree that political involvement was a larger concern to the average American in the 1850s than today. Politics was, in one of its functions, a form of mass entertainment, a spectacle with rallies, parades, and colorful personalities. Leading politicians, moreover, often served as a focus for popular interests, aspirations, and values.

Historian Allan Nevins, for instance, writes of political rallies in 1856 with turnouts of anywhere from twenty to fifty thousand men and women. Voter turnouts even ran as high as 84% by 1860. An abundance of new parties emerged 1854–56, including the Republicans, People's party men, Anti-Nebraskans, Fusionists,

Know Nothings, Know-Somethings (anti-slavery nativists), Maine Lawites, Temperance men, Rum Democrats, Silver Gray Whigs, Hindus, Hard Shell Democrats, Soft Shells, Half Shells and Adopted Citizens. By 1858, they were mostly gone, and politics divided four ways. Republicans controlled most Northern states with a strong Democratic minority. The Democrats were split North and South and fielded two tickets in 1860. Southern non-Democrats tried different coalitions; most supported the Constitutional Union party in 1860.

Many Southern states held constitutional conventions in 1851 to consider the questions of nullification and secession. With the exception of South Carolina, whose convention election did not even offer the option of "no secession" but rather "no secession without the collaboration of other states", the Southern conventions were dominated by Unionists who voted down articles of secession.

Economics

Historians today generally agree that economic conflicts were not a major cause of the war. While an economic basis to the sectional crisis was popular among the "Progressive school" of historians from the 1910s to the 1940s, few professional historians now subscribe to this explanation. According to economic historian Lee A. Craig, "In fact, numerous studies by economic historians over the past several decades reveal that economic conflict was not an inherent condition of North-South relations during the antebellum era and did not cause the Civil War."

When numerous groups tried at the last minute in 1860–61 to find a compromise to avert war, they did not turn to economic policies. The three major attempts at compromise, the

Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Jo ...

, the

Corwin Amendment

The Corwin Amendment was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that was never adopted. It would shield "domestic institutions" of the states from the federal constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by ...

and the Washington Peace Conference, addressed only the slavery-related issues of fugitive slave laws, personal liberty laws, slavery in the territories and interference with slavery within the existing slave states.

Economic value of slavery to the South

Historian James L. Huston emphasizes the role of slavery as an economic institution. In October 1860

William Lowndes Yancey

William Lowndes Yancey (August 10, 1814July 27, 1863) was an American journalist, politician, orator, diplomat and an American leader of the Southern secession movement. A member of the group known as the Fire-Eaters, Yancey was one of the m ...

, a leading advocate of secession, placed the value of Southern-held slaves at $2.8 billion. Huston writes:

The

cotton gin greatly increased the efficiency with which cotton could be harvested, contributing to the consolidation of "

King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

" as the backbone of the economy of the Deep South, and to the entrenchment of the system of slave labor on which the cotton plantation economy depended. Any chance that the South would industrialize was over.

The tendency of

monoculture

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of growing one crop species in a field at a time. Monoculture is widely used in intensive farming and in organic farming: both a 1,000-hectare/acre cornfield and a 10-ha/acre field of organic kale are ...

cotton plantings to lead to soil exhaustion created a need for cotton planters to move their operations to new lands, and therefore to the westward expansion of slavery from the

Eastern seaboard into new areas (e.g., Alabama, Mississippi, and beyond to

East Texas

East Texas is a broadly defined cultural, geographic, and ecological region in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Texas that comprises most of 41 counties. It is primarily divided into Northeast and Southeast Texas. Most of the region cons ...

).

Regional economic differences

The South, Midwest, and Northeast had quite different economic structures. They traded with each other and each became more prosperous by staying in the Union, a point many businessmen made in 1860–61. However,

Charles A. Beard in the 1920s made a highly influential argument to the effect that these differences caused the war (rather than slavery or constitutional debates). He saw the industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the agrarian Midwest against the plantation South. Critics challenged his image of a unified Northeast and said that the region was in fact highly diverse with many different competing economic interests. In 1860–61, most business interests in the Northeast opposed war.

After 1950, only a few mainstream historians accepted the Beard interpretation, though it was accepted by

libertarian economists. Historian

Kenneth Stampp, who abandoned Beardianism after 1950, sums up the scholarly consensus: "Most historians ... now see no compelling reason why the divergent economies of the North and South should have led to disunion and civil war; rather, they find stronger practical reasons why the sections, whose economies neatly complemented one another, should have found it advantageous to remain united."

Free labor vs. pro-slavery arguments

Historian

Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African-American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstruc ...

argued that a free-labor ideology dominated thinking in the North, which emphasized economic opportunity. By contrast, Southerners described free labor as "greasy mechanics, filthy operators, small-fisted farmers, and moonstruck theorists". They strongly opposed the

homestead laws that were proposed to give free farms in the west, fearing the small farmers would oppose plantation slavery. Indeed, opposition to homestead laws was far more common in secessionist rhetoric than opposition to tariffs. Southerners such as Calhoun argued that slavery was "a positive good", and that slaves were more civilized and morally and intellectually improved because of slavery.

Religious conflict over the slavery question

Led by

Mark Noll

Mark Allan Noll (born 1946) is an American historian specializing in the history of Christianity in the United States. He holds the position of Research Professor of History at Regent College, having previously been Francis A. McAnaney Professor o ...

, a body of scholarship

has highlighted the fact that the American debate over slavery became a shooting war in part because the two sides reached diametrically opposite conclusions based on reading the same authoritative source of guidance on moral questions: the

King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

of the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

.

After the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and the

disestablishment of government-sponsored churches, the U.S. experienced the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

, a massive

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

revival. Without centralized church authorities, American Protestantism was heavily reliant on the Bible, which was read in the standard 19th-century Reformed

hermeneutic of "common sense", literal interpretation as if the Bible were speaking directly about the modern American situation instead of events that occurred in a much different context, millennia ago.

By the mid-19th century this form of religion and Bible interpretation had become a dominant strand in American religious, moral and political discourse, almost serving as a de facto state religion.

The Bible, interpreted under these assumptions, seemed to clearly suggest that slavery was Biblically justified:

"The pro-slavery South could point to slaveholding by the godly patriarch Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

(Gen 12:5; 14:14; 24:35–36; 26:13–14), a practice that was later incorporated into Israelite national law (Lev 25:44–46). It was never denounced by Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

, who made slavery a model of discipleship (Mk 10:44). The Apostle Paul supported slavery, counseling obedience to earthly masters (Eph 6:5–9; Col 3:22–25) as a duty in agreement with "the sound words of our Lord Jesus Christ and the teaching which accords with godliness" (1 Tim 6:3). Because slaves were to remain in their present state unless they could win their freedom (1 Cor 7:20–24), he sent the fugitive slave Onesimus

Onesimus ( grc-gre, Ὀνήσιμος, Onēsimos, meaning "useful"; died , according to Catholic tradition), also called Onesimus of Byzantium and The Holy Apostle Onesimus in the Eastern Orthodox Church, was probably a slave to Philemon of Colo ...

back to his owner Philemon (Phlm 10–20). The abolitionist north had a difficult time matching the pro-slavery south passage for passage. ... Professor Eugene Genovese, who has studied these biblical debates over slavery in minute detail, concludes that the pro-slavery faction clearly emerged victorious over the abolitionists except for one specious argument based on the so-called Curse of Ham

The curse of Ham is described in the Book of Genesis as imposed by the patriarch Noah upon Ham's son Canaan. It occurs in the context of Noah's drunkenness and is provoked by a shameful act perpetrated by Noah's son Ham, who "saw the nakedness o ...

(Gen 9:18–27). For our purposes, it is important to realize that the South won this crucial contest with the North by using the prevailing hermeneutic, or method of interpretation, on which both sides agreed. So decisive was its triumph that the South mounted a vigorous counterattack on the abolitionists as infidels who had abandoned the plain words of Scripture for the secular ideology of the Enlightenment."

Protestant churches in the U.S., unable to agree on what God's Word said about slavery, ended up with schisms between Northern and Southern branches: the

Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

in 1844, the

Baptists in 1845, and the

Presbyterian Church in 1857.

These splits presaged the subsequent split in the nation: "The churches played a major role in the dividing of the nation, and it is probably true that it was the splits in the churches which made a final split of the nation inevitable."

The conflict over how to interpret the Bible was central:

"The theological crisis occasioned by reasoning like onservative Presbyterian theologian James H.Thornwell's was acute. Many Northern Bible-readers and not a few in the South ''felt'' that slavery was evil. They somehow ''knew'' the Bible supported them in that feeling. Yet when it came to using the Bible as it had been used with such success to evangelize and civilize the United States, the sacred page was snatched out of their hands. Trust in the Bible and reliance upon a Reformed, literal hermeneutic had created a crisis that only bullets, not arguments, could resolve."

The result:

"The question of the Bible and slavery in the era of the Civil War was never a simple question. The issue involved the American expression of a Reformed literal hermeneutic, the failure of hermeneutical alternatives to gain cultural authority, and the exercise of deeply entrenched intuitive racism, as well as the presence of Scripture as an authoritative religious book and slavery as an inherited social-economic relationship. The North—forced to fight on unfriendly terrain that it had helped to create—lost the exegetical war. The South certainly lost the shooting war. But constructive orthodox theology was the major loser when American believers allowed bullets instead of hermeneutical self-consciousness to determine what the Bible said about slavery. For the history of theology in America, the great tragedy of the Civil War is that the most persuasive theologians were the Rev. Drs. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

."

There were many causes of the Civil War, but the religious conflict, almost unimaginable in modern America, cut very deep at the time. Noll and others highlight the significance of the religion issue for the famous phrase in

Lincoln's second inaugural: "Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other."

The territorial crisis and the United States Constitution

Between 1803 and 1854, the United States achieved a vast expansion of territory through purchase (

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

), negotiation (

Adams–Onís Treaty,

Oregon Treaty), and conquest (the

Mexican Cession). Of the states carved out of these territories by 1845, all had entered the union as slave states: Louisiana, Missouri, Arkansas, Florida, and Texas, as well as the southern portions of Alabama and Mississippi.

[McPherson, 2007, p. 14.] With the conquest of northern Mexico, including California, in 1848, slaveholding interests looked forward to the institution flourishing in these lands as well. Southerners also anticipated annexing as slave states Cuba (see

Ostend Manifesto

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain while implying that the U.S. should declare war if Spain refused. Cuba's annex ...

), Mexico, and Central America (see

Golden Circle (proposed country)).

Northern free soil interests vigorously sought to curtail any further expansion of slave soil. It was these territorial disputes that the proslavery and antislavery forces collided over.

The existence of slavery in the southern states was far less politically polarizing than the explosive question of the territorial expansion of the institution in the west. Moreover, Americans were informed by two well-established readings of the Constitution regarding human bondage: that the slave states had complete autonomy over the institution within their boundaries, and that the domestic slave trade—trade among the states—was immune to federal interference. The only feasible strategy available to attack slavery was to restrict its expansion into the new territories. Slaveholding interests fully grasped the danger that this strategy posed to them. Both the South and the North believed: "The power to decide the question of slavery for the territories was the power to determine the future of slavery itself."

By 1860, four doctrines had emerged to answer the question of federal control in the territories, and they all claimed to be sanctioned by the Constitution, implicitly or explicitly. Two of the "conservative" doctrines emphasized the written text and historical precedents of the founding document, while the other two doctrines developed arguments that transcended the Constitution.

[Bestor, 1964, p. 21]

One of the "conservative" theories, represented by the

Constitutional Union Party, argued that the historical designation of free and slave apportionments in territories should become a Constitutional mandate. The

Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Jo ...

of 1860 was an expression of this view.

[Bestor, 1964, p. 20]

The second doctrine of Congressional preeminence, championed by

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and the

Republican Party, insisted that the Constitution did not bind legislators to a policy of balance—that slavery could be excluded altogether in a territory at the discretion of Congress

—with one caveat: the

due process clause of the Fifth Amendment must apply. In other words, Congress could restrict human bondage, but never establish it.

The

Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

announced this position in 1846.

Of the two doctrines that rejected federal authority, one was articulated by northern Democrat of Illinois Senator

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, and the other by southern Democratic Senator

Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and Senator

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

of Kentucky.

Douglas devised the doctrine of territorial or "popular" sovereignty, which declared that the settlers in a territory had the same rights as states in the Union to establish or disestablish slavery—a purely local matter.

Congress, having created the territory, was barred, according to Douglas, from exercising any authority in domestic matters. To do so would violate historic traditions of self-government, implicit in the US Constitution.

[Bestor, 1964, p. 23] The

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

of 1854 legislated this doctrine.

The fourth in this quartet is the theory of state sovereignty ("

states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

"),