Oder–Neisse Line on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the

During the 4th and 5th centuries, in what is known as the

During the 4th and 5th centuries, in what is known as the

Originally, Germany was to retain Stettin, while the Poles were to annex

Originally, Germany was to retain Stettin, while the Poles were to annex  The eventual border was not the most far-reaching territorial change that was proposed. There were suggestions to include areas further west so that Poland could include the small minority population of ethnic Slavic

The eventual border was not the most far-reaching territorial change that was proposed. There were suggestions to include areas further west so that Poland could include the small minority population of ethnic Slavic

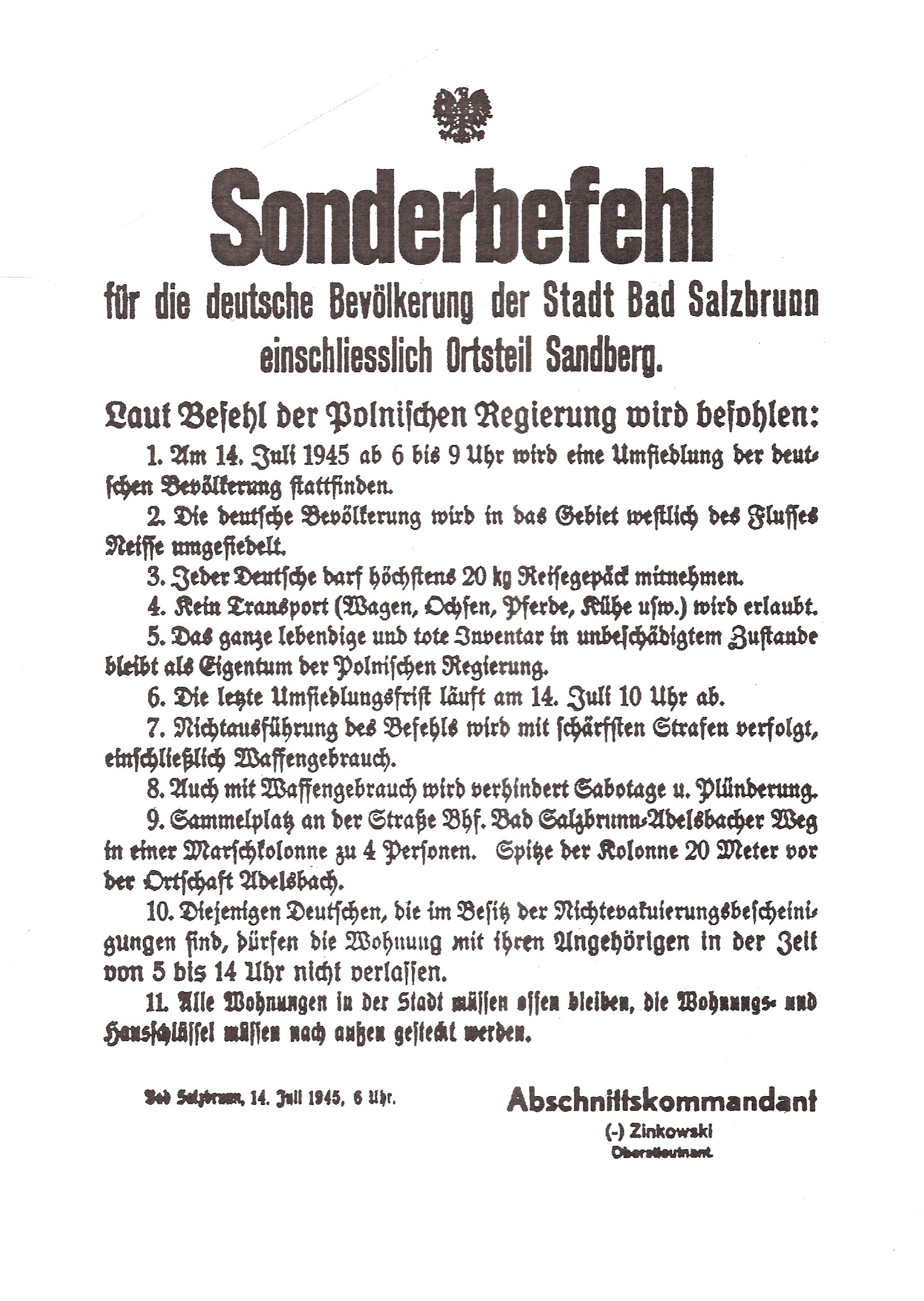

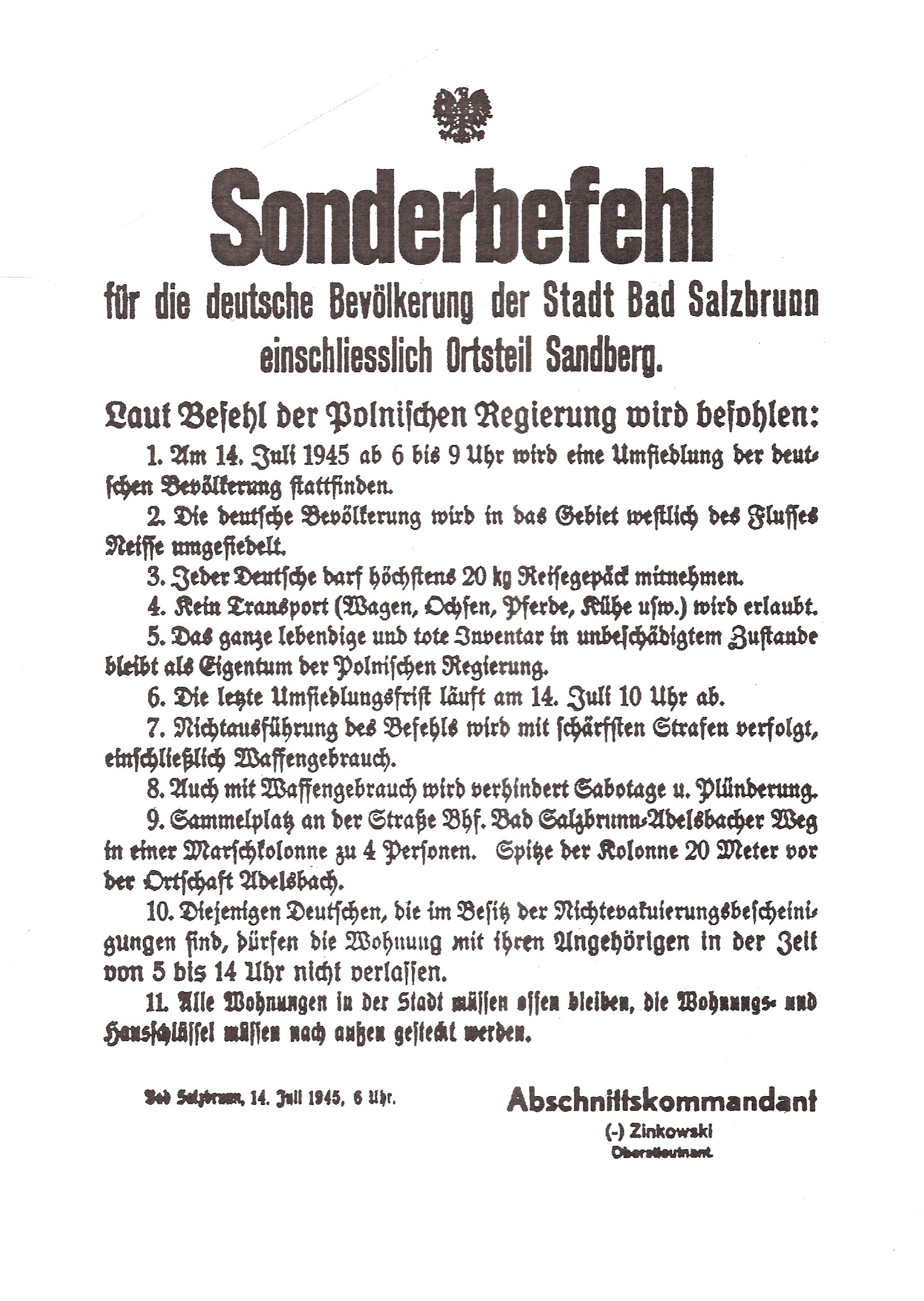

At Potsdam, Stalin argued for the Oder–Neisse line on the grounds that the Polish Government demanded this frontier and that there were no longer any Germans left east of this line. Later the Russians admitted that at least "a million Germans" (still far lower than the true number) still remained in the area at that time. Several Polish Communist leaders appeared at the conference to advance arguments for an Oder–Western Neisse frontier. The port of Stettin was demanded for Eastern European exports. If Stettin was Polish, then "in view of the fact that the supply of water is found between the Oder and the Lausitzer Neisse, if the Oder's tributaries were controlled by someone else the river could be blocked." Soviet forces had initially expelled Polish administrators who tried to seize control of Stettin in May and June, and the city was governed by a German communist-appointed mayor, under the surveillance of the Soviet occupiers, until 5 July 1945.

At Potsdam, Stalin argued for the Oder–Neisse line on the grounds that the Polish Government demanded this frontier and that there were no longer any Germans left east of this line. Later the Russians admitted that at least "a million Germans" (still far lower than the true number) still remained in the area at that time. Several Polish Communist leaders appeared at the conference to advance arguments for an Oder–Western Neisse frontier. The port of Stettin was demanded for Eastern European exports. If Stettin was Polish, then "in view of the fact that the supply of water is found between the Oder and the Lausitzer Neisse, if the Oder's tributaries were controlled by someone else the river could be blocked." Soviet forces had initially expelled Polish administrators who tried to seize control of Stettin in May and June, and the city was governed by a German communist-appointed mayor, under the surveillance of the Soviet occupiers, until 5 July 1945.

James Byrnes – who had been appointed as U.S. Secretary of State earlier that month – later advised the Soviets that the U.S. was prepared to concede the area east of the Oder and the Eastern Neisse to Polish administration, and for it not to consider it part of the Soviet occupation zone, in return for a moderation of Soviet demands for reparations from the Western occupation zones. An Eastern Neisse boundary would have left Germany with roughly half of

James Byrnes – who had been appointed as U.S. Secretary of State earlier that month – later advised the Soviets that the U.S. was prepared to concede the area east of the Oder and the Eastern Neisse to Polish administration, and for it not to consider it part of the Soviet occupation zone, in return for a moderation of Soviet demands for reparations from the Western occupation zones. An Eastern Neisse boundary would have left Germany with roughly half of

Those territories were known in Poland as the Regained or Recovered Territories, a term based on the claim that they were in the past the possession of the

Those territories were known in Poland as the Regained or Recovered Territories, a term based on the claim that they were in the past the possession of the

''"The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy Over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland"''

ed. by Polonsky and Michlic, p. 466 The creation of a picture of the new territories as an "integral part of historical Poland" in the post-war era had the aim of forging Polish settlers and repatriates arriving there into a coherent community loyal to the new Communist regime.Martin Åberg, Mikael Sandberg, ''Social Capital and Democratisation: Roots of Trust in Post-Communist Poland and Ukraine'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003,

Google Print, p. 79

/ref> The term was in use immediately following the end of

Winston Churchill was not present at the end of the Conference, since the results of the British elections had made it clear that he had been defeated. Churchill later claimed that he would never have agreed to the Oder–Western Neisse line, and in his famous

Winston Churchill was not present at the end of the Conference, since the results of the British elections had made it clear that he had been defeated. Churchill later claimed that he would never have agreed to the Oder–Western Neisse line, and in his famous  Not only were the German territorial changes of the

Not only were the German territorial changes of the

The East German Socialist Unity Party (SED), founded 1946, originally rejected the Oder–Neisse line. Under Soviet occupation and heavy pressure by Moscow, the official phrase ''Friedensgrenze'' (border of peace) was promulgated in March–April 1947 at the Moscow Foreign Ministers Conference. The

The East German Socialist Unity Party (SED), founded 1946, originally rejected the Oder–Neisse line. Under Soviet occupation and heavy pressure by Moscow, the official phrase ''Friedensgrenze'' (border of peace) was promulgated in March–April 1947 at the Moscow Foreign Ministers Conference. The

The West German definition of the "de jure" borders of Germany was based on the determinations of the Potsdam Agreement, which placed the German territories (as of 31 December 1937) east of the Oder–Neisse line "''under the administration of the Polish State''" while "''the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement''". The recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was thus only reserved to a final peace settlement with reunited Germany.Article VIII. B of the Potsdam Agreement: "In conformity with the agreement on Poland reached at the Crimea Conference the three heads of government have sought the opinion of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in regard to the accession of territory in the north 'end west which Poland should receive. The President of the National Council of Poland and members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity have been received at the Conference and have fully presented their views. The three heads of government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.

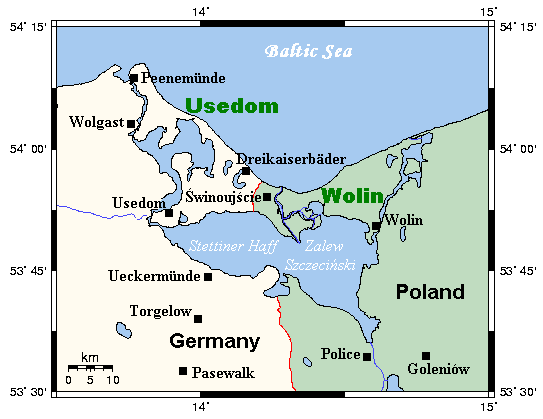

The three heads of government agree that, pending the final determination of Poland's western frontier, the former German territories cast of a line running from the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinamunde, and thence along the Oder River to the confluence of the western Neisse River and along the Western Neisse to the Czechoslovak frontier, including that portion of East Prussia not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in accordance with the understanding reached at this conference and including the area of the former free city of Danzig, shall be under the administration of the Polish State and for such purposes should not be considered as part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany."

In West Germany, where the majority of the displaced refugees found refuge, recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was long regarded as unacceptable. Right from the beginning of his Chancellorship in 1949, Adenauer refused to accept the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern frontier, and made it quite clear that if Germany ever reunified, the Federal Republic would lay claim to all of the land that had belonged to Germany as at 1 January 1937.Schwarz, Hans Peter ''Konrad Adenauer: From the German Empire to the Federal Republic, 1876–1952'', Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1995 page 638. Adenauer's rejection of the border adjustments resulting from the Potsdam agreement was viewed critically by some in Poland. Soon after the agreement was signed, both the US and Soviet Union accepted the border as the de facto border of Poland. United States Secretary James Byrnes accepted the Western Neisse as the provisional Polish border. While in his Stuttgart Speech he played around with an idea of modification of borders (in Poland's favor), giving fuel to speculation by German nationalists and revisionists, the State department confessed that the speech was simply intended to "smoke out Molotov's attitude on the eve of elections in Germany". The Adenauer government went to the Constitutional Court to receive a ruling that declared that legally speaking the frontiers of the Federal Republic were those of Germany as at 1 January 1937, that the Potsdam Declaration of 1945 which announced that the Oder–Neisse line was Germany's "provisional" eastern border was invalid, and that as such the Federal Republic considered all of the land east of the Oder–Neisse line to be "illegally" occupied by Poland and the Soviet Union. The American historian

The West German definition of the "de jure" borders of Germany was based on the determinations of the Potsdam Agreement, which placed the German territories (as of 31 December 1937) east of the Oder–Neisse line "''under the administration of the Polish State''" while "''the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement''". The recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was thus only reserved to a final peace settlement with reunited Germany.Article VIII. B of the Potsdam Agreement: "In conformity with the agreement on Poland reached at the Crimea Conference the three heads of government have sought the opinion of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in regard to the accession of territory in the north 'end west which Poland should receive. The President of the National Council of Poland and members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity have been received at the Conference and have fully presented their views. The three heads of government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.

The three heads of government agree that, pending the final determination of Poland's western frontier, the former German territories cast of a line running from the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinamunde, and thence along the Oder River to the confluence of the western Neisse River and along the Western Neisse to the Czechoslovak frontier, including that portion of East Prussia not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in accordance with the understanding reached at this conference and including the area of the former free city of Danzig, shall be under the administration of the Polish State and for such purposes should not be considered as part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany."

In West Germany, where the majority of the displaced refugees found refuge, recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was long regarded as unacceptable. Right from the beginning of his Chancellorship in 1949, Adenauer refused to accept the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern frontier, and made it quite clear that if Germany ever reunified, the Federal Republic would lay claim to all of the land that had belonged to Germany as at 1 January 1937.Schwarz, Hans Peter ''Konrad Adenauer: From the German Empire to the Federal Republic, 1876–1952'', Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1995 page 638. Adenauer's rejection of the border adjustments resulting from the Potsdam agreement was viewed critically by some in Poland. Soon after the agreement was signed, both the US and Soviet Union accepted the border as the de facto border of Poland. United States Secretary James Byrnes accepted the Western Neisse as the provisional Polish border. While in his Stuttgart Speech he played around with an idea of modification of borders (in Poland's favor), giving fuel to speculation by German nationalists and revisionists, the State department confessed that the speech was simply intended to "smoke out Molotov's attitude on the eve of elections in Germany". The Adenauer government went to the Constitutional Court to receive a ruling that declared that legally speaking the frontiers of the Federal Republic were those of Germany as at 1 January 1937, that the Potsdam Declaration of 1945 which announced that the Oder–Neisse line was Germany's "provisional" eastern border was invalid, and that as such the Federal Republic considered all of the land east of the Oder–Neisse line to be "illegally" occupied by Poland and the Soviet Union. The American historian  To Hans Peter Schwarz, Adenauer's refusal to accept the Oder–Neisse line was in large part motivated by domestic politics, especially his desire to win the votes of the domestic lobby of those Germans who had been expelled from areas east of the Oder–Neisse line. 16% of the electorate in 1950 were people who fled or were expelled after the war, forming a powerful political force . As a result, the CDU, the CSU, the FDP and the SPD all issued statements opposing the Oder–Neisse line and supporting ''Heimatrecht'' ("right to one's homeland", i.e. that the expellees be allowed to return to their former homes). Adenauer greatly feared the power of the expellee lobby, and told his cabinet in 1950 that he was afraid of "unbearable economic and political unrest" if the government did not champion all of the demands of the expellee lobby. In addition, Adenauer's rejection of the Oder–Neisse line was intended to be a deal-breaker if negotiations ever began to reunite Germany on terms that Adenauer considered unfavorable such as the neutralization of Germany as Adenauer knew well that the Soviets would never consider revising the Oder–Neisse line. Finally Adenauer's biographer, the German historian Hans Peter Schwarz has argued that Adenauer may have genuinely believed that Germany had the right to retake the land lost east of the Oder and Neisse rivers, despite all of the image problems this created for him in the United States and western Europe. By contrast, the Finnish historian Pertti Ahonen—citing numerous private statements made by Adenauer that Germany's eastern provinces were lost forever and expressing contempt for the expellee leaders as delusional in believing that they were actually going to return one day to their former homes—has argued that Adenauer had no interest in really challenging the Oder–Neisse line. Ahonen wrote that Adenauer "saw his life's work in anchoring the Federal Republic irrevocably to the anti-Communist West and no burning interest in East European problems—or even German reunification." Adenauer's stance on the Oder–Neisse line was to create major image problems for him in the Western countries in the 1950s, where many regarded his revanchist views on where Germany's eastern borders ought to be with considerable distaste, and only the fact that East Germany was between the Federal Republic and Poland prevented this from becoming a major issue in relations with the West.

To Hans Peter Schwarz, Adenauer's refusal to accept the Oder–Neisse line was in large part motivated by domestic politics, especially his desire to win the votes of the domestic lobby of those Germans who had been expelled from areas east of the Oder–Neisse line. 16% of the electorate in 1950 were people who fled or were expelled after the war, forming a powerful political force . As a result, the CDU, the CSU, the FDP and the SPD all issued statements opposing the Oder–Neisse line and supporting ''Heimatrecht'' ("right to one's homeland", i.e. that the expellees be allowed to return to their former homes). Adenauer greatly feared the power of the expellee lobby, and told his cabinet in 1950 that he was afraid of "unbearable economic and political unrest" if the government did not champion all of the demands of the expellee lobby. In addition, Adenauer's rejection of the Oder–Neisse line was intended to be a deal-breaker if negotiations ever began to reunite Germany on terms that Adenauer considered unfavorable such as the neutralization of Germany as Adenauer knew well that the Soviets would never consider revising the Oder–Neisse line. Finally Adenauer's biographer, the German historian Hans Peter Schwarz has argued that Adenauer may have genuinely believed that Germany had the right to retake the land lost east of the Oder and Neisse rivers, despite all of the image problems this created for him in the United States and western Europe. By contrast, the Finnish historian Pertti Ahonen—citing numerous private statements made by Adenauer that Germany's eastern provinces were lost forever and expressing contempt for the expellee leaders as delusional in believing that they were actually going to return one day to their former homes—has argued that Adenauer had no interest in really challenging the Oder–Neisse line. Ahonen wrote that Adenauer "saw his life's work in anchoring the Federal Republic irrevocably to the anti-Communist West and no burning interest in East European problems—or even German reunification." Adenauer's stance on the Oder–Neisse line was to create major image problems for him in the Western countries in the 1950s, where many regarded his revanchist views on where Germany's eastern borders ought to be with considerable distaste, and only the fact that East Germany was between the Federal Republic and Poland prevented this from becoming a major issue in relations with the West.

On 1 May 1956, the West German Foreign Minister

On 1 May 1956, the West German Foreign Minister Treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Poland on the confirmation of the frontier between them, 14 November 1990

PDF) came into force on 16 January 1992, together with a second one, a

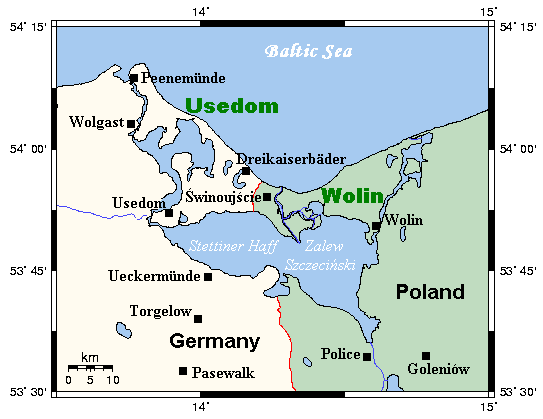

The border divided several cities into two parts –

The border divided several cities into two parts –

online

* * * * * * * * * * *

* [https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/DEU-POL1990CF.PDF Treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Poland on the confirmation of the frontier between them, 14 November 1990](PDF)Treaty confirming the border between Germany and Poland (Warsaw, 14 November 1990)

in Polish and German)

The Oder Neisse Line Problem

(German) (PDF)

Speaking Frankly

James F. Byrnes; Excerpt on the

Triumph and Tragedy

Churchill's statement to the House of Commons

27, February 1945, Describing the outcome of Yalta

ARENA Working Papers WP 97/19 Jorunn Sem Fure Department of History, University of Bergen {{DEFAULTSORT:Oder-Neisse Line Aftermath of World War II in Poland Aftermath of World War II in Germany Partition (politics) 1945 establishments in Europe

international border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political border ...

between Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

and Lusatian Neisse rivers and meets the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

in the north, just west of the ports of Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Świnoujście

Świnoujście (; german: Swinemünde ; nds, Swienemünn; all three meaning "Świna ivermouth"; csb, Swina) is a city and seaport on the Baltic Sea and Szczecin Lagoon, located in the extreme north-west of Poland. Situated mainly on the islands ...

(German: ''Stettin'' and ''Swinemünde'').

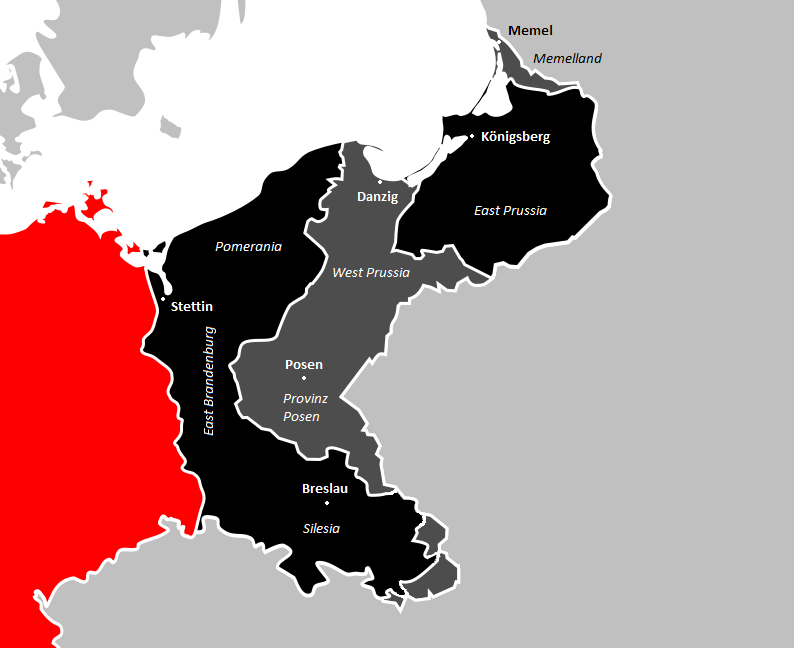

All prewar German territories east of the line and within the 1937 German boundaries—comprising nearly one quarter (23.8 percent) of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

—were ceded under the changes decided at the postwar Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

(Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

), with the greatest part becoming part of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. The remainder, consisting of northern East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

with the German city of Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

(renamed Kaliningrad

Kaliningrad ( ; rus, Калининград, p=kəlʲɪnʲɪnˈɡrat, links=y), until 1946 known as Königsberg (; rus, Кёнигсберг, Kyonigsberg, ˈkʲɵnʲɪɡzbɛrk; rus, Короле́вец, Korolevets), is the largest city and ...

), was allocated to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, as the Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and admin ...

of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

(today Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

). However this did not become completely official until the peace treaty for Germany was signed. The ethnic Germans in these territories either fled or were expelled to the west Oder–Neisse line.

The Oder–Neisse line marked the border between East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

and Poland from 1950 to 1990. The two Communist governments agreed to the border in 1950, while West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

, after a period of refusal, adhered to the border, with reservations, in 1970.

After the Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Natio ...

, newly reunified Germany and Poland accepted the line as their border in the 1990 German–Polish Border Treaty. Previously, Germany renounced all territorial claim beyond East Germany and West Germany with the fact that these two German countries signed the peace treaty (Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (german: Vertrag über die abschließende Regelung in Bezug auf Deutschland;

rus, Договор об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Ге� ...

) on 12 September 1990.

History

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

, Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

(ancient Germans) seized control of the decaying Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the South and established new kingdoms within it. Meanwhile, formerly Germanic areas in Eastern Europe and present-day Eastern Germany in west of Oder-Neisse line, were settled by Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

.

After capturing what is now Eastern Germany from the Slavs, the eastern border of East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

(Germany) extended to the Oder-Neisse line and bordered Piast Poland (Polish are also a people of Slavs).

The lower River Oder in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

was Piast Poland

The period of rule by the Piast dynasty between the 10th and 14th centuries is the first major stage of the history of the Polish state. The dynasty was founded by a series of dukes listed by the chronicler Gall Anonymous in the early 12th ce ...

's western border from the 10th until the 13th century. From around the time of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, some proposed restoring this line, in the belief that it would provide protection against Germany. One of the first proposals was made in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

. Later, when the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

gained power, the German territory to the east of the line was militarised by Germany with a view to a future war, and the Polish population faced Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In lin ...

.Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej nr 9-10/2005, "Polski Dziki Zachód" – ze Stanisławem Jankowiakiem, Czesławem Osękowskim i Włodzimierzem Suleją rozmawia Barbara Polak, pages 4–28 The policies of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

also encouraged nationalism among the German minority in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

.

Before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Poland's western border with Germany had been fixed under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

of 1919. It partially followed the historic border between the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

(Germany) and Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

(Poland), but with certain adjustments that were intended to reasonably reflect the ethnic compositions of small areas near the traditional provincial borders. However Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

had been divided (beside a plebiscite with a 59,8 % pro-German result), leaving areas populated by a Polish minority on the German side and a significant German minority on the Polish side. Moreover, the border left Germany divided into two portions by the Polish Corridor and the independent Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

, which had an overwhelmingly German population (96.7%), but was split from Germany to help secure Poland's strategic access to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

.

Considerations during the war

Background

Between the wars, the concept of "Western thought" ('' myśl zachodnia'') became popular among some Polish nationalists. The "Polish motherland territories" were defined by scholars, likeZygmunt Wojciechowski

Zygmunt Wojciechowski (27 April 1900 – 14 October 1955) was a Polish historian and nationalist politician. Born in 1900 in then-Austria, he obtained a doctorate from medieval history at Lviv University. In 1925 he moved to Poznań, where ...

, as the areas included in Piast Poland

The period of rule by the Piast dynasty between the 10th and 14th centuries is the first major stage of the history of the Polish state. The dynasty was founded by a series of dukes listed by the chronicler Gall Anonymous in the early 12th ce ...

in the 10th century. Some Polish historians called for the "return" of territories up to the river Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

. The proponents of these ideas, in prewar Poland often described as a "group of fantasists", were organized in the National Party, which was also opposed to the government of Poland, the Sanacja."Myśl zachodnia Ruchu Narodowego w czasie II wojny światowej" dr Tomasz Kenar. Dodatek Specjalny IPN Nowe Państwo 1/2010 The proposal to establish the border along the Oder and Neisse was not seriously considered for a long time. After World War II the Polish Communists, lacking their own expertise regarding the Western border, adopted the National Democratic concept of western thought.

After Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

invaded and occupied Poland, some Polish politicians started to see a need to alter the border with Germany. A secure border was seen as essential, especially in the light of Nazi atrocities. During the war, Nazi Germany committed genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

against Poland's population, especially Jews, whom they classified as '' Untermenschen'' ("sub-humans"). Alteration to the western border was seen as a punishment for the Germans for their atrocities and a compensation for Poland. The participation in the genocide by German minorities and their paramilitary organizations, such as the ''Selbstschutz

''Selbstschutz'' (German for "self-protection") is the name given to different iterations of ethnic-German self-protection units formed both after the First World War and in the lead-up to the Second World War.

The first incarnation of the ''Selb ...

'' ("self defense"), and support for Nazism among German society also connected the issue of border changes with the idea of population transfers intended to avoid such events in the future.

Initially the Polish government in exile envisioned territorial changes after the war which would incorporate East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, Danzig (Gdańsk) and the Oppeln (Opole) Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

n region into post-war Poland, along with a straightening of the Pomeranian border and minor acquisition in the Lauenburg (Lębork) area. The border changes were to provide Poland with a safe border and to prevent the Germans from using Eastern Pomerania and East Prussia as strategic assets against Poland. Only with the changing situation during the war were these territorial proposals modified. In October 1941 the exile newspaper '' Dziennik Polski'' postulated a postwar Polish western border that would include East Prussia, Silesia up to the Lausitzer Neisse

The Lusatian Neisse (german: Lausitzer Neiße; pl, Nysa Łużycka; cs, Lužická Nisa; Upper Sorbian: ''Łužiska Nysa''; Lower Sorbian: ''Łužyska Nysa''), or Western Neisse, is a river in northern Central Europe.Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

's mouth. While these territorial claims were regarded as "megalomaniac" by the Soviet ambassador in London, in October 1941 Stalin announced the "return of East Prussia to Slavdom" after the war. On 16 December 1941 Stalin remarked in a meeting with the British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

, though inconsistent in detail, that Poland should receive all German territory up to the river Oder. In May 1942 General Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Prior to the First World War, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause for Polish i ...

, Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile, sent two memoranda to the US government, sketching a postwar Polish western border along the Oder and Neisse (inconsistent about the Eastern Glatzer Neisse

The Eastern Neisse, also known by its Polish name of Nysa Kłodzka (german: Glatzer Neiße, cs, Kladská Nisa), is a river in southwestern Poland, a left tributary of the Oder, with a length of 188 km (21st longest) and a basin area of 4,570& ...

and the Western Lausitzer Neisse). However, the proposal was dropped by the government-in-exile in late 1942.

In post-war Poland the government described the Oder–Neisse line as the result of tough negotiations between Polish Communists and Stalin.

However, according to the modern Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state resea ...

, Polish aspirations had no impact on the final outcome; rather the idea of a westward shift of the Polish border was adopted synthetically by Stalin, who was the final arbiter in the matter. Stalin's political goals as well as his desire to foment enmity between Poles and Germans influenced his idea of a swap of western for eastern territory, thus ensuring control over both countries. As with before the war, some fringe groups advocated restoring the old border between Poland and Germany.

Tehran Conference

At theTehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

in late 1943, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

raised the subject of Poland's western frontier and its extension to the River Oder. While the Americans were not interested in discussing any border changes at that time, Roosevelt agreed that in general the Polish border should be extended West to the Oder, while Polish eastern borders should be shifted westwards; he also admitted that it was due to elections at home he could not express his position publicly. British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

wrote in his diary that "A difficulty is that the Americans are terrified of the subject which oosevelt advisorHarry opkinscalled 'political dynamite' for their elections. But, as I told him, if we cannot get a solution, Polish-Soviet relations six months from now, with Soviet armies in Poland, will be infinitely worse and elections nearer."

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

compared the westward shift of Poland to soldiers taking two steps "left close" and declared in his memoirs: "If Poland trod on some German toes that could not be helped, but there must be a strong Poland."

The British government formed a clear position on the issue and at the first meeting of the European Advisory Commission on 14 January 1944, recommended "that East Prussia and Danzig, and possibly other areas, will ultimately be given to Poland" as well as agreeing on a Polish "frontier on the Oder".

Yalta Conference

In February 1945, American and British officials met inYalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

and agreed on the basics on Poland's future borders. In the east, the British agreed to the Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

but recognised that the US might push for Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

to be included in post-war Poland. In the west, Poland should receive part of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, Danzig, the eastern tip of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

. President Franklin D. Roosevelt said that it would "make it easier for me at home" if Stalin were generous to Poland with respect to Poland's eastern frontiers. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

said a Soviet concession on that point would be admired as "a gesture of magnanimity" and declared that, with respect to Poland's post-war government, the British would "never be content with a solution which did not leave Poland a free and independent state." With respect to Poland's western frontiers, Stalin noted that the Polish Prime Minister in exile, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, had been pleased when Stalin had told him Poland would be granted Stettin/Szczecin and the German territories east of the Western Neisse. Yalta was the first time that the Soviets openly declared support for a German-Polish frontier on the Western as opposed to the Eastern Neisse. Churchill objected to the Western Neisse frontier, saying that "it would be a pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food that it got indigestion." He added that many Britons would be shocked if such large numbers of Germans were driven out of these areas, to which Stalin responded that "many Germans" had "already fled before the Red Army." Poland's western frontier was ultimately left to be decided at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

.

Polish and Soviet demands

Originally, Germany was to retain Stettin, while the Poles were to annex

Originally, Germany was to retain Stettin, while the Poles were to annex East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

with Königsberg (now Kaliningrad

Kaliningrad ( ; rus, Калининград, p=kəlʲɪnʲɪnˈɡrat, links=y), until 1946 known as Königsberg (; rus, Кёнигсберг, Kyonigsberg, ˈkʲɵnʲɪɡzbɛrk; rus, Короле́вец, Korolevets), is the largest city and ...

). The Polish government had in fact demanded this since the start of World War II in 1939, because of East Prussia's strategic position that allegedly undermined the defense of Poland. Other territorial changes proposed by the Polish government were the transfer of the Silesian region of Oppeln and the Pomeranian regions of Danzig, Bütow and Lauenburg, and the straightening of the border somewhat in Western Pomerania.

However, Stalin decided that he wanted Königsberg as a year-round warm water port for the Soviet Navy, and he argued that the Poles should receive Stettin instead. The prewar Polish government-in-exile had little to say in these decisions, but insisted on retaining the city of Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

(Lvov, Lemberg, now L'viv) in Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

. Stalin refused to concede, and instead proposed that all of Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

including Breslau (Polish: Wrocław) be given to Poland. Many Poles from Lwów would later be moved to populate the city.

Sorbs

Sorbs ( hsb, Serbja, dsb, Serby, german: Sorben; also known as Lusatians, Lusatian Serbs and Wends) are a indigenous West Slavic ethnic group predominantly inhabiting the parts of Lusatia located in the German states of Saxony and Branden ...

who lived near Cottbus

Cottbus (; Lower Sorbian: ''Chóśebuz'' ; Polish: Chociebuż) is a university city and the second-largest city in Brandenburg, Germany. Situated around southeast of Berlin, on the River Spree, Cottbus is also a major railway junction with exte ...

and Bautzen

Bautzen () or Budyšin () is a hill-top town in eastern Saxony, Germany, and the administrative centre of the district of Bautzen. It is located on the Spree river. In 2018 the town's population was 39,087. Until 1868, its German name was ''Budi ...

.

The precise location of the western border was left open. The western Allies accepted in general that the Oder would be the future western border of Poland. Still in doubt was whether the border should follow the eastern or western Neisse, and whether Stettin, now Szczecin, which lay west of the Oder, should remain German or be placed in Poland (with an expulsion of the German population). Stettin was the traditional seaport of Berlin. It had a dominant German population and a small Polish minority that numbered 2,000 in the interwar period.Tadeusz Białecki, "Historia Szczecina" Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1992 Wrocław. Pages 9, 20–55, 92–95, 258–260, 300–306.Polonia szczecińska 1890–1939 Anna Poniatowska Bogusław Drewniak, Poznań 1961 The western Allies sought to place the border on the eastern Neisse at Breslau, but Stalin refused to budge. Suggestions of a border on the Bóbr (Bober) were also rejected by the Soviets.

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

in his memoirs said: ''"I had only one desire – that Poland's borders were moved as far west as possible."''

Potsdam Conference

Concessions

James Byrnes – who had been appointed as U.S. Secretary of State earlier that month – later advised the Soviets that the U.S. was prepared to concede the area east of the Oder and the Eastern Neisse to Polish administration, and for it not to consider it part of the Soviet occupation zone, in return for a moderation of Soviet demands for reparations from the Western occupation zones. An Eastern Neisse boundary would have left Germany with roughly half of

James Byrnes – who had been appointed as U.S. Secretary of State earlier that month – later advised the Soviets that the U.S. was prepared to concede the area east of the Oder and the Eastern Neisse to Polish administration, and for it not to consider it part of the Soviet occupation zone, in return for a moderation of Soviet demands for reparations from the Western occupation zones. An Eastern Neisse boundary would have left Germany with roughly half of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

– including the majority of Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, r ...

(Breslau), the former provincial capital and the largest city in the region. The Soviets insisted that the Poles would not accept this. The next day Byrnes told the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

that the Americans would reluctantly concede to the Western Neisse.

Byrnes' concession undermined the British position, and although the British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in th ...

raised objections, the British eventually agreed to the American concession. In response to American and British statements that the Poles were claiming far too much German territory, Stanisław Mikołajczyk argued that "the western lands were needed as a reservoir to absorb the Polish population east of the Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

, Poles who returned from the West, and Polish people who lived in the overcrowded central districts of Poland." The U.S. and the U.K. were also negative towards the idea of giving Poland an occupation zone in Germany. However, on 29 July, President Truman handed Molotov a proposal for a temporary solution whereby the U.S. accepted Polish administration of land as far as the Oder and eastern Neisse until a final peace conference determined the boundary. In return for this large concession, the U.S. demanded that "each of the occupation powers take its share of reparations from its own ccupationZone and provide for admission of Italy into the United Nations." The Soviets stated that they were not pleased "because it denied Polish administration of the area between the two Neisse rivers."

On 29 July Stalin asked Bolesław Bierut, the head of the Soviet-controlled Polish government

The Government of Poland takes the form of a unitary parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the President is the head of state and the Prime Minister is the head of government. However, its form of government has also been id ...

, to accept in consideration of the large American concessions. The Polish delegation decided to accept a boundary of the administration zone at "somewhere between the western Neisse and the Kwisa". Later that day the Poles changed their mind: "Bierut, accompanied by Rola-Zymierski, returned to Stalin and argued against any compromise with the Americans. Stalin told his Polish protégés that he would defend their position at the conference."

During the Potsdam Conference in 1945, the Western Allies briefly advocated a Polish-German border along the Oder, Bóbr and Kwisa rivers, but were rejected by Joseph Stalin, who had already committed himself to the Oder-Neisse line.

Finally on 1 August 1945, the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, in anticipation of the final peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

, placed the German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line formally under Polish administrative control. It was also decided that all Germans remaining in the new and old Polish territory should be expelled.

Recovered territories

Those territories were known in Poland as the Regained or Recovered Territories, a term based on the claim that they were in the past the possession of the

Those territories were known in Poland as the Regained or Recovered Territories, a term based on the claim that they were in the past the possession of the Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branche ...

dynasty of Polish kings, Polish fiefs or included in the parts lost to Prussia during the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

. The term was widely exploited by Propaganda in the People's Republic of Poland.An explanation note i''"The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy Over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland"''

ed. by Polonsky and Michlic, p. 466 The creation of a picture of the new territories as an "integral part of historical Poland" in the post-war era had the aim of forging Polish settlers and repatriates arriving there into a coherent community loyal to the new Communist regime.Martin Åberg, Mikael Sandberg, ''Social Capital and Democratisation: Roots of Trust in Post-Communist Poland and Ukraine'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003,

Google Print, p. 79

/ref> The term was in use immediately following the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

when it was part of the Communist indoctrination of the Polish settlers in those territories. The final agreements in effect compensated Poland with of former German territory in exchange for of land lying east of the Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

– Polish areas occupied by the Soviet Union. Poles and Polish Jews from the Soviet Union were the subject of a process called "repatriation" (settlement within the territory of post-war Poland). Not all of them were repatriated: some were imprisoned or deported to work camps in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

or Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

.

One reason for this version of the new border was that it was the shortest possible border between Poland and Germany. It is only 472 km (293 miles) long, from one of the northernmost points of the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

to one of the southernmost points of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

at the Oder estuary.

World War II aftermath

Winston Churchill was not present at the end of the Conference, since the results of the British elections had made it clear that he had been defeated. Churchill later claimed that he would never have agreed to the Oder–Western Neisse line, and in his famous

Winston Churchill was not present at the end of the Conference, since the results of the British elections had made it clear that he had been defeated. Churchill later claimed that he would never have agreed to the Oder–Western Neisse line, and in his famous Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its ...

speech declared that

The Russian-dominated Polish Government has been encouraged to make enormous and wrongful inroads upon Germany, and mass expulsions of millions of Germans on a scale grievous and undreamed-of are now taking place.

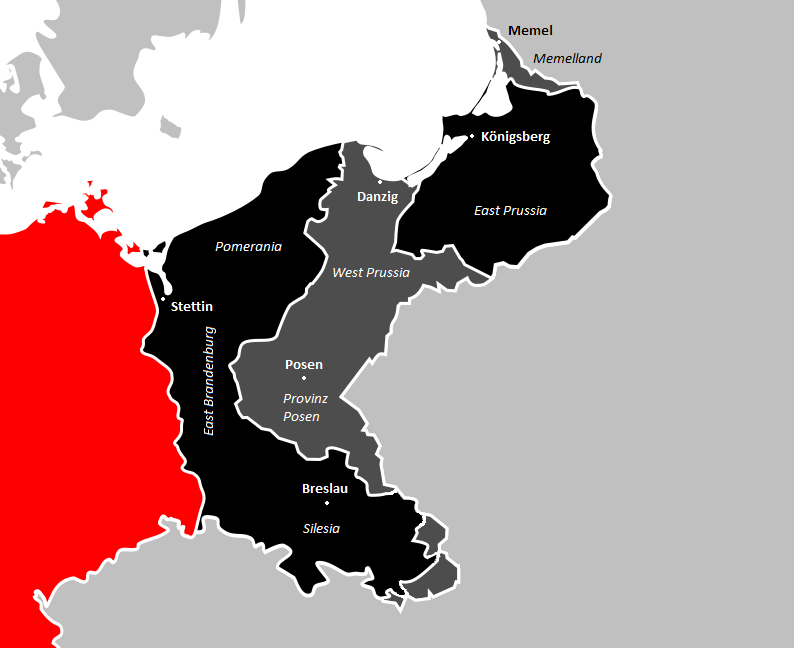

Not only were the German territorial changes of the

Not only were the German territorial changes of the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

s reversed, but the border was moved westward, deep into territory which had been in 1937 part of Germany with an almost exclusively German population. The new line placed almost all of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

, more than half of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, the eastern portion of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

, a small area of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

, the former Free City of Danzig and the southern two-thirds of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

( Masuria and Warmia) within Poland (see Former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

). The northeastern third of East Prussia was directly annexed by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, with the Memelland becoming part of the Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

and the bulk of the territory forming the new Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and admin ...

of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

.

These territorial changes were followed by large-scale population transfers, involving 14 million people all together from the whole of Eastern Europe, including many people already shifted during the war. Nearly all remaining Germans from the territory annexed by Poland were expelled, while Polish persons who had been displaced into Germany, usually as slave laborers, returned to settle in the area. In addition to this, the Polish population originating from the eastern half of the former Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

, now annexed by the Soviet Union, was mostly expelled and transferred to the newly acquired territories.

Most Poles supported the new border, mostly out of fear of renewed German aggression and German irredentism. The border was also presented as a just consequence for the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

German state's initiation of World War II and the subsequent genocide against Poles and the attempt to destroy Polish statehood, as well as for the territorial losses of eastern Poland to the Soviet Union, mainly western Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

. It has been asserted that resentment towards the expelled German population on the part of the Poles was based on the fact that the majority of that population was loyal to the Nazis during the invasion and occupation, and the active role some of them played in the persecution and mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

of Poles and Jews. These circumstances allegedly have impeded sensitivity among Poles with respect to the expulsion committed during the aftermath of World War II.

The new order was in Stalin's interests, because it enabled the Soviet Communists to present themselves as the primary maintainer of Poland's new western border. It also provided the Soviet Union with territorial gains from part of East Prussia and the eastern part of the Second Republic of Poland.

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

James F. Byrnes outlined the official position of the U.S. government regarding the Oder–Neisse line in his Stuttgart Speech of 6 September 1946:

At Potsdam specific areas which were part of Germany were provisionally assigned to the Soviet Union and to Poland, subject to the final decisions of the Peace Conference. ..With regard to Silesia and other eastern German areas, the assignment of this territory to Poland by Russia for administrative purposes had taken place before the Potsdam meeting. The heads of government agreed that, pending the final determination of Poland's western frontier, Silesia and other eastern German areas should be under the administration of the Polish state and for such purposes should not be considered as a part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. However, as the Protocol of the Potsdam Conference makes clear, the heads of government did not agree to support at the peace settlement the cession of this particular area. The Soviets and the Poles suffered greatly at the hands of Hitler's invading armies. As a result of the agreement at Yalta, Poland ceded to the Soviet Union territory east of the Curzon Line. Because of this, Poland asked for revision of her northern and western frontiers. The United States will support revision of these frontiers in Poland's favor. However, the extent of the area to be ceded to Poland must be determined when the final settlement is agreed upon.The speech was met with shock in Poland and Deputy Prime Minister Mikołajczyk immediately issued a response declaring that retention of Polish territories based on the Oder–Neisse line was matter of life and death. Byrnes, who accepted Western Neisse as provisional Polish border,No exit: America and the German problem, 1943–1954, page 94, James McAllister, Cornell University Press 2002Peter H. Merkl, German Unification, 2004. Penn State Press, p. 338.Pertti Ahonen, After the expulsion: West Germany and Eastern Europe, 1945–1990, 2003. Oxford University Press, pp. 26–27 in fact did not state that such a change would take place (as was read by Germans who hoped for support to regain the lost territories). The purpose of the speech and associated US diplomatic activities was as propaganda aimed at Germany by Western Powers, who could blame the Polish-German border and German expulsions on Moscow alone. In the late 1950s, by the time of Dwight D. Eisenhower's Presidency, the United States had largely accepted the Oder–Neisse line as final and did not support German demands regarding the border, while officially declaring a need for a final settlement in a peace treaty. In the mid-1960s the U.S. government accepted the Oder–Neisse line as binding and agreed that there would be no changes to it in the future. German revisionism regarding the border began to cost West Germany sympathies among its western allies. In 1959, France officially issued a statement supporting the Oder–Neisse line, which created controversy in West Germany. The Oder–Neisse line was, however, never formally recognized by the United States until the revolutionary changes of 1989 and 1990.

German recognition of the border

East Germany

The East German Socialist Unity Party (SED), founded 1946, originally rejected the Oder–Neisse line. Under Soviet occupation and heavy pressure by Moscow, the official phrase ''Friedensgrenze'' (border of peace) was promulgated in March–April 1947 at the Moscow Foreign Ministers Conference. The

The East German Socialist Unity Party (SED), founded 1946, originally rejected the Oder–Neisse line. Under Soviet occupation and heavy pressure by Moscow, the official phrase ''Friedensgrenze'' (border of peace) was promulgated in March–April 1947 at the Moscow Foreign Ministers Conference. The German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

and Poland's Communist government signed the Treaty of Zgorzelec in 1950 recognizing the Oder–Neisse line, officially designated by the Communists as the "Border of Peace and Friendship".

In 1952 Stalin made recognition of the Oder–Neisse line as a permanent boundary one of the conditions for the Soviet Union to agree to a reunification of Germany (see Stalin Note

The Stalin Note, also known as the March Note, was a document delivered to the representatives of the Western Allies (the United Kingdom, France, and the United States) from the Soviet Union in separated Germany including the two countries in W ...

). The offer was rejected by the West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

.

West Germany

The West German definition of the "de jure" borders of Germany was based on the determinations of the Potsdam Agreement, which placed the German territories (as of 31 December 1937) east of the Oder–Neisse line "''under the administration of the Polish State''" while "''the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement''". The recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was thus only reserved to a final peace settlement with reunited Germany.Article VIII. B of the Potsdam Agreement: "In conformity with the agreement on Poland reached at the Crimea Conference the three heads of government have sought the opinion of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in regard to the accession of territory in the north 'end west which Poland should receive. The President of the National Council of Poland and members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity have been received at the Conference and have fully presented their views. The three heads of government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.

The three heads of government agree that, pending the final determination of Poland's western frontier, the former German territories cast of a line running from the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinamunde, and thence along the Oder River to the confluence of the western Neisse River and along the Western Neisse to the Czechoslovak frontier, including that portion of East Prussia not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in accordance with the understanding reached at this conference and including the area of the former free city of Danzig, shall be under the administration of the Polish State and for such purposes should not be considered as part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany."

In West Germany, where the majority of the displaced refugees found refuge, recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was long regarded as unacceptable. Right from the beginning of his Chancellorship in 1949, Adenauer refused to accept the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern frontier, and made it quite clear that if Germany ever reunified, the Federal Republic would lay claim to all of the land that had belonged to Germany as at 1 January 1937.Schwarz, Hans Peter ''Konrad Adenauer: From the German Empire to the Federal Republic, 1876–1952'', Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1995 page 638. Adenauer's rejection of the border adjustments resulting from the Potsdam agreement was viewed critically by some in Poland. Soon after the agreement was signed, both the US and Soviet Union accepted the border as the de facto border of Poland. United States Secretary James Byrnes accepted the Western Neisse as the provisional Polish border. While in his Stuttgart Speech he played around with an idea of modification of borders (in Poland's favor), giving fuel to speculation by German nationalists and revisionists, the State department confessed that the speech was simply intended to "smoke out Molotov's attitude on the eve of elections in Germany". The Adenauer government went to the Constitutional Court to receive a ruling that declared that legally speaking the frontiers of the Federal Republic were those of Germany as at 1 January 1937, that the Potsdam Declaration of 1945 which announced that the Oder–Neisse line was Germany's "provisional" eastern border was invalid, and that as such the Federal Republic considered all of the land east of the Oder–Neisse line to be "illegally" occupied by Poland and the Soviet Union. The American historian

The West German definition of the "de jure" borders of Germany was based on the determinations of the Potsdam Agreement, which placed the German territories (as of 31 December 1937) east of the Oder–Neisse line "''under the administration of the Polish State''" while "''the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement''". The recognition of the Oder-Neisse Line as permanent was thus only reserved to a final peace settlement with reunited Germany.Article VIII. B of the Potsdam Agreement: "In conformity with the agreement on Poland reached at the Crimea Conference the three heads of government have sought the opinion of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in regard to the accession of territory in the north 'end west which Poland should receive. The President of the National Council of Poland and members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity have been received at the Conference and have fully presented their views. The three heads of government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.