Occupation of Poland (1939–1945) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The occupation of Poland by

Conquest, Robert (1991). "Stalin: Breaker of Nations". New York, N.Y.: Viking. Around 6 million Polish citizens—nearly 21.4% of Poland's population—died between 1939 and 1945 as a result of the occupation, See als

review

/ref>Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami, ed. Tomasz Szarota and Wojciech Materski, Warszawa, IPN 2009,

) half of whom were ethnic Poles and the other half of whom were

Introduction reproduced here

)

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 27–29 The size of these annexed territories was approximately with approximately 10.5 million inhabitants.Piotr Eberhardt,

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pagea 25 The remaining block of territory, of about the same size and inhabited by about 11.5 million, was placed under a German administration called the By the end of the invasion the Soviet Union had taken over 51.6% of the territory of Poland (about ), with over 13,200,000 people. The ethnic composition of these areas was as follows: 38% Poles (~5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees, mostly Jews (198,000), who fled from areas occupied by Germany. All territory invaded by the

By the end of the invasion the Soviet Union had taken over 51.6% of the territory of Poland (about ), with over 13,200,000 people. The ethnic composition of these areas was as follows: 38% Poles (~5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees, mostly Jews (198,000), who fled from areas occupied by Germany. All territory invaded by the

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 30–31 The end of the war saw the USSR occupy all of Poland and most of eastern Germany. The Soviets gained recognition of their pre-1941 annexations of Polish territory; as compensation, substantial portions of eastern Germany were ceded to Poland, whose borders were significantly shifted westwards.Piotr Eberhardt,

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 32–34

From the beginning, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany was intended as fulfilment of the future plan of the German Reich described by

From the beginning, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany was intended as fulfilment of the future plan of the German Reich described by  Those plans began to be implemented almost immediately after German troops took control of Poland. As early as October 1939, many Poles were expelled from the annexed lands in order to make room for German colonizers. Only those Poles who had been selected for

Those plans began to be implemented almost immediately after German troops took control of Poland. As early as October 1939, many Poles were expelled from the annexed lands in order to make room for German colonizers. Only those Poles who had been selected for

" This was in spite of racial theory that falsely regarded most Polish leaders as actually being of "German blood",Richard C. Lukas,

', 1939–1945. Hippocrene Books, New York, 2001. and partly because of it, on the grounds that German blood must not be used in the service of a foreign nation. After Germany lost the war, the

The German People's List (''

The German People's List (''

In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated 25 May 1940,

In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated 25 May 1940,

Google Print, p.71-73

The decrees required Poles to wear identifying purple P's on their clothing, made them subject to a curfew, and banned them from using public transportation as well as many German "cultural life" centres and "places of amusement" (this included churches and restaurants). Sexual relations between Germans and Poles were forbidden as ''

File:Polenabzeichen.jpg, Polish-forced-workers' badge

File:Pflichten_der_polen.jpg, Poster in German and Polish listing decrees of labour obligations

File:Verordnung 30 september 1939.JPG, Notice of death penalty for Poles refusing to work during harvest

Labor shortages in the German war economy became critical especially after German defeat in the battle of

A network of

A network of

Following the

Following the

Poles: Victims of the Nazi Era

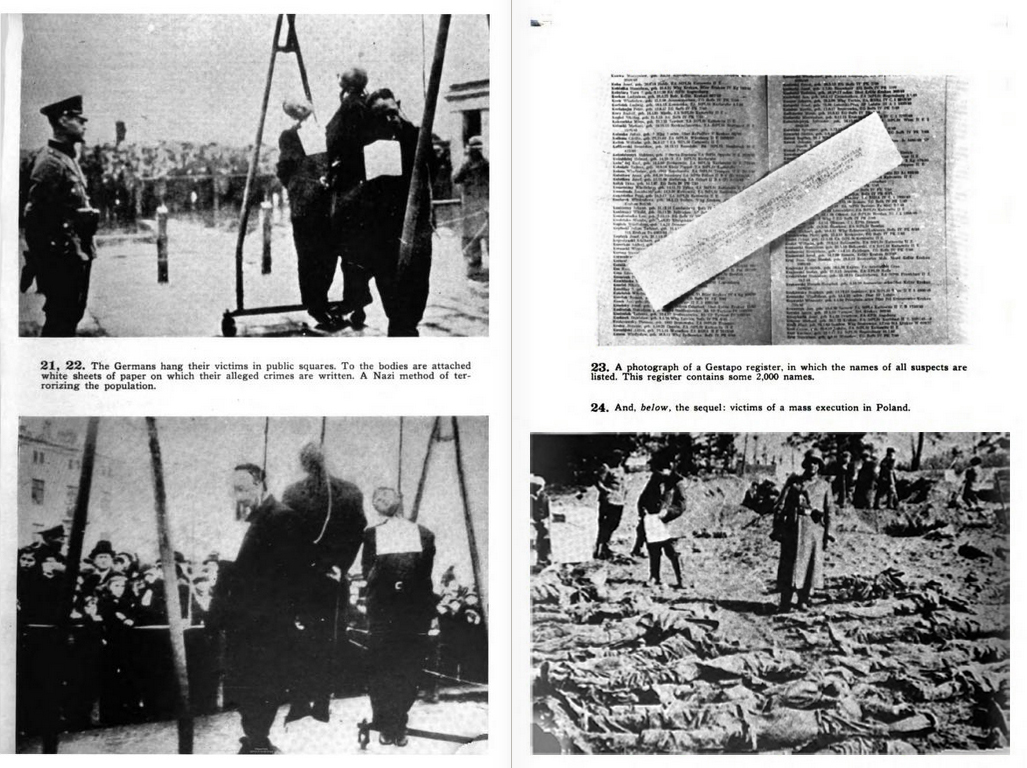

The extermination of the Polish elite was the first stage of the Nazis' plan to destroy the Polish nation and its culture. The disappearance of the Poles' leadership was seen as necessary to the establishment of the Germans as the Poles' sole leaders. Proscription lists ('' Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen''), prepared before the war started, identified more than 61,000 members of the Polish elite and

The extermination of the Polish elite was the first stage of the Nazis' plan to destroy the Polish nation and its culture. The disappearance of the Poles' leadership was seen as necessary to the establishment of the Germans as the Poles' sole leaders. Proscription lists ('' Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen''), prepared before the war started, identified more than 61,000 members of the Polish elite and

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Page 46 Already during the 1939 German invasion, dedicated units of SS and police (the '' The Nazis also persecuted the Catholic Church in Poland and other, smaller religions.

Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where they set about systematically dismantling the Church – arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen and nuns were murdered or sent to concentration and labor camps. Already in 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. Primate of Poland, Cardinal August Hlond, submitted an official account of the persecutions of the Polish Church to the Vatican.The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942; pp. 34–51 In his final observations for

The Nazis also persecuted the Catholic Church in Poland and other, smaller religions.

Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where they set about systematically dismantling the Church – arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen and nuns were murdered or sent to concentration and labor camps. Already in 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. Primate of Poland, Cardinal August Hlond, submitted an official account of the persecutions of the Polish Church to the Vatican.The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942; pp. 34–51 In his final observations for

Polish women deported to Germany as forced labourers and who bore children were a common victim of this policy, with their infants regularly taken. If the child passed the battery of racial, physical and psychological tests, they were sent on to Germany for "Germanization". At least 4,454 children were given new German names, forbidden to use Polish language, and reeducated in Nazi institutions. Few were ever reunited with their original families. Those deemed as unsuitable for Germanization for being "not

Despite the military defeat of the Polish Army in September 1939, the Polish government itself never surrendered, instead evacuating West, where it formed the

Despite the military defeat of the Polish Army in September 1939, the Polish government itself never surrendered, instead evacuating West, where it formed the

The Polish Government-in-Exile's Home Delegature

'. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved 4 April 2011. The main role of the civilian branch of the Underground State was to preserve the continuity of the Polish state as a whole, including its institutions. These institutions included the police, the courts, and In response to the occupation, Poles formed one of the largest underground movements in Europe. Resistance to the

In response to the occupation, Poles formed one of the largest underground movements in Europe. Resistance to the

The Polish Underground State and The Home Army (1939–45)

'. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved 14 March 2008. There was also the People's Army (Polish ''Armia Ludowa'' or AL), backed by the Soviet Union and controlled by the

. Encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 21 December 2006. In February 1942, when AK was formed, it numbered about 100,000 members. In the beginning of 1943, it had reached a strength of about 200,000. In the summer of 1944 when

.

Poland had a large Jewish population, and according to Davies, more Jews were both killed and rescued in Poland, than in any other nation, the rescue figure usually being put at between 100,000 and 150,000.Norman Davies; ''Rising '44: the Battle for Warsaw''; Viking; 2003; p.200 Thousands of Poles have been honoured as

Poland had a large Jewish population, and according to Davies, more Jews were both killed and rescued in Poland, than in any other nation, the rescue figure usually being put at between 100,000 and 150,000.Norman Davies; ''Rising '44: the Battle for Warsaw''; Viking; 2003; p.200 Thousands of Poles have been honoured as

With archival photos. The population in the General Government's territory was initially about 12 million in an area of 94,000 square kilometres, but this increased as about 860,000 Poles and Jews were expelled from the German-annexed areas and "resettled" in the General Government. Offsetting this was the German campaign of extermination of the Polish

By the end of the Polish Defensive War, the Soviet Union took over 52.1% of Poland's territory (~200,000 km2), with over 13,700,000 people. The estimates vary; Prof. Elżbieta Trela-Mazur gives the following numbers in regards to the ethnic composition of these areas: 38% Poles (ca. 5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees from areas occupied by Germany, most of them Jews (198,000). Areas occupied by the USSR were annexed to Soviet territory, with the exception of the

By the end of the Polish Defensive War, the Soviet Union took over 52.1% of Poland's territory (~200,000 km2), with over 13,700,000 people. The estimates vary; Prof. Elżbieta Trela-Mazur gives the following numbers in regards to the ethnic composition of these areas: 38% Poles (ca. 5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees from areas occupied by Germany, most of them Jews (198,000). Areas occupied by the USSR were annexed to Soviet territory, with the exception of the  The Soviet Union had ceased to recognize the Polish state at the start of the invasion.Telegrams sent by

The Soviet Union had ceased to recognize the Polish state at the start of the invasion.Telegrams sent by

No. 317

of 10 September 1939

of 16 September 1939

of 17 September 1939. The

(Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939, refused by Polish ambassador Wacław Grzybowski). Retrieved 15 November 2006. As a result, the two governments never officially declared war on each other. The Soviets therefore did not classify Polish military prisoners as prisoners of war but as rebels against the new legal government of Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia. The Soviets killed tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war. Some, like General

(Executed Hospital). Tygodnik Zamojski, 15 September 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2006. The Soviets also executed all the Polish officers they captured after the

"The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field

", ''Studies in Intelligence'', Winter 1999–2000. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

p. 20–24.

/ref> The Poles and the Soviets re-established diplomatic relations in 1941, following the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement; but the Soviets broke them off again in 1943 after the Polish government demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyn burial pits. The Soviets then lobbied the Western Allies to recognize the pro-Soviet Polish puppet government of Wanda Wasilewska in Moscow. On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany had changed the secret terms of the

p.132.

/ref> They began confiscating,

Represje 1939–41. Aresztowani na Kresach Wschodnich

(Repressions 1939–41. Arrested on the Eastern Borderlands.) Retrieved 15 November 2006. and deported between 350,000 and 1,500,000, of whom between 150,000 and 1,000,000 died, mostly civilians.AFP/Expatica,

'', expatica.com, 30 August 2009Rieber, pp. 14, 32–37.

/ref> Subsequently, all institutions of the dismantled Polish state were closed down and reopened under the Soviet appointed supervisors. Lwow University and many other schools were reopened soon but they were restarted anew as Soviet institutions rather than continuing their old legacy. Lwow University was reorganized in accordance with the Statute Books for Soviet Higher Schools. The tuition, that along with the institution's Polonophile traditions, kept the university inaccessible to most of the rural Ukrainophone population, was abolished and several new chairs were opened, particularly the chairs of

online

, Polish language

, last retrieved on 10 December 2005, Polish language As the Soviet Union did not sign any international convention on

In 1940 and the first half of 1941, the Soviets deported more than 1,200,000 Poles, most in four mass deportations. The first deportation took place 10 February 1940, with more than 220,000 sent to northern European Russia; the second on 13 April 1940, sending 320,000 primarily to Kazakhstan; a third wave in June–July 1940 totaled more than 240,000; the fourth occurred in June 1941, deporting 300,000. Upon resumption of Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations in 1941, it was determined based on Soviet information that more than 760,000 of the deportees had died – a large part of those dead being children, who had comprised about a third of deportees.Assembly of Captive European Nations, First Session

Approximately 100,000 former Polish citizens were arrested during the two years of Soviet occupation.Represje 1939–41 Aresztowani na Kresach Wschodnich

In 1940 and the first half of 1941, the Soviets deported more than 1,200,000 Poles, most in four mass deportations. The first deportation took place 10 February 1940, with more than 220,000 sent to northern European Russia; the second on 13 April 1940, sending 320,000 primarily to Kazakhstan; a third wave in June–July 1940 totaled more than 240,000; the fourth occurred in June 1941, deporting 300,000. Upon resumption of Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations in 1941, it was determined based on Soviet information that more than 760,000 of the deportees had died – a large part of those dead being children, who had comprised about a third of deportees.Assembly of Captive European Nations, First Session

Approximately 100,000 former Polish citizens were arrested during the two years of Soviet occupation.Represje 1939–41 Aresztowani na Kresach Wschodnich

(Repressions 1939–41. Arrested on the Eastern Borderlands.) Ośrodek Karta. Last accessed on 15 November 2006. The prisons soon got severely overcrowded. with detainees suspected of anti-Soviet activities and the NKVD had to open dozens of ad hoc prison sites in almost all towns of the region. The wave of arrests led to forced resettlement of large categories of people (

, last retrieved on 14 March 2006, Polish language) to over 2 million (mostly World War II estimates by the underground). The earlier number is based on records made by the NKVD and does not include roughly 180,000 prisoners of war, also in Soviet captivity. Most modern historians estimate the number of all people deported from areas taken by the Soviet Union during this period at between 800,000 and 1,500,000; for example R. J. Rummel gives the number of 1,200,000 million; Tony Kushner and Katharine Knox give 1,500,000 in their ''Refugees in an Age of Genocide''

p.219

in his ''Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917''

p.132

See also: According to

Google Print, p.78

/ref> According to the Soviet law, all residents of the annexed area, dubbed by the Soviets as citizens of ''former Poland'', automatically acquired Soviet citizenship. However, actual conferral of citizenship still required the individual's consent and the residents were strongly pressured for such consent.

/ref> The refugees who opted out were threatened with repatriation to Nazi controlled territories of Poland.Jan T. Gross, op.cit.,

188

/ref>

p. 35

/ref> Pre-war Poland was portrayed as a capitalist state based on exploitation of the working people and ethnic minorities. Soviet propaganda claimed that unfair treatment of non-Poles by the

page 36

/ref> The death toll of the initial Soviet-inspired terror campaign remains unknown.

Around 6 million Polish citizens – nearly 21.4% of the pre-war population of the

Around 6 million Polish citizens – nearly 21.4% of the pre-war population of the

Review of Piotrowski's ''Poland's Holocaust''

UC Santa Barbara Over 90% of the death toll involved non-military losses, as most civilians were targets of various deliberate actions by the Germans and Soviets. Both occupiers wanted not only to gain Polish territory, but also to destroy

A review of the Piotrowski book ''Poland's Holocaust''

* Michael Phayer

'Et Papa tacet': the genocide of Polish Catholics

* ttp://www.chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra# Testimonies concerning German occupation of Poland in testimony database 'Chronicles of Terror' {{DEFAULTSORT:Occupation Of Poland (1939-1945) Jewish Polish history Military history of Poland Germany–Poland relations

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

(1939–1945) began with the German-Soviet invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

in September 1939, and it was formally concluded with the defeat of Germany by the Allies in May 1945. Throughout the entire course of the occupation, the territory of Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR) both of which intended to eradicate Poland's culture and subjugate its people. In the summer-autumn of 1941, the lands which were annexed by the Soviets were overrun by Germany in the course of the initially successful German attack on the USSR. After a few years of fighting, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

drove the German forces out of the USSR and crossed into Poland from the rest of Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europ ...

.

Sociologist Tadeusz Piotrowski argues that both occupying powers were hostile to the existence of Poland's sovereignty, people

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of prope ...

, and the culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

and aimed to destroy them. Before Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, Germany and the Soviet Union coordinated their Poland-related policies, most visibly in the four Gestapo–NKVD conferences, where the occupiers discussed their plans to deal with the Polish resistance movement."Terminal horror suffered by so many millions of innocent Jewish, Slavic, and other European peoples as a result of this meeting of evil minds is an indelible stain on the history and integrity of Western civilization, with all of its humanitarian pretensions" (Note: "this meeting" refers to the most famous third (Zakopane) conference).Conquest, Robert (1991). "Stalin: Breaker of Nations". New York, N.Y.: Viking. Around 6 million Polish citizens—nearly 21.4% of Poland's population—died between 1939 and 1945 as a result of the occupation, See als

review

/ref>Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami, ed. Tomasz Szarota and Wojciech Materski, Warszawa, IPN 2009,

) half of whom were ethnic Poles and the other half of whom were

Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

. Over 90% of the deaths were non-military losses, because most civilians were deliberately targeted in various actions which were launched by the Germans and Soviets. Overall, during German occupation of pre-war Polish territory, 1939–1945, the Germans murdered 5,470,000–5,670,000 Poles, including 3,000,000 Jews in what was described as a deliberate and systematic genocide during the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

.

In August 2009, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state resea ...

(IPN) researchers estimated Poland's dead (including Polish Jews) at between 5.47 and 5.67 million (due to German actions) and 150,000 (due to Soviet), or around 5.62 and 5.82 million total.Wojciech Materski and Tomasz Szarota (eds.).''Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami.''Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state resea ...

(IPN) Warszawa 2009 Introduction reproduced here

)

Administration

In September 1939 Poland was invaded and occupied by two powers:Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, acting in accordance with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. Germany acquired 48.4% of the former Polish territory. Under the terms of two decrees by Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, with Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's agreement (8 and 12 October 1939), large areas of western Poland were annexed by Germany.Piotr Eberhardt, http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 27–29 The size of these annexed territories was approximately with approximately 10.5 million inhabitants.Piotr Eberhardt,

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pagea 25 The remaining block of territory, of about the same size and inhabited by about 11.5 million, was placed under a German administration called the

General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

(in German: ''Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete''), with its capital at Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

. A German lawyer and prominent Nazi, Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Par ...

, was appointed Governor-General of this occupied area on 12 October 1939. Most of the administration outside strictly local level was replaced by German officials. Non-German population on the occupied lands were subject to forced resettlement, Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

, economic exploitation, and slow but progressive extermination.

A small strip of land, about with 200,000 inhabitants that had been part of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

before 1938, was ceded by Germany to its ally, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

.

Poles comprised an overwhelming majority the population of the territories that came under the control of Germany, in contrast the areas annexed by the Soviet Union contained a diverse array of peoples, the population being split into bilingual provinces, some of which had large ethnic Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities, many of whom welcomed the Soviets due in part to communist agitation by Soviet emissaries. Nonetheless Poles still comprised a plurality of the population in all territories annexed by the Soviet Union.

By the end of the invasion the Soviet Union had taken over 51.6% of the territory of Poland (about ), with over 13,200,000 people. The ethnic composition of these areas was as follows: 38% Poles (~5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees, mostly Jews (198,000), who fled from areas occupied by Germany. All territory invaded by the

By the end of the invasion the Soviet Union had taken over 51.6% of the territory of Poland (about ), with over 13,200,000 people. The ethnic composition of these areas was as follows: 38% Poles (~5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees, mostly Jews (198,000), who fled from areas occupied by Germany. All territory invaded by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

was annexed to the Soviet Union (after a rigged election), and split between the Belarusian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, with the exception of the Wilno area taken from Poland, which was transferred to sovereign Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

for several months and subsequently annexed by the Soviet Union in the form of the Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

on 3 August 1940. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

in 1941, most of the Polish territories annexed by the Soviets were attached to the enlarged General Government.Piotr Eberhardt, http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 30–31 The end of the war saw the USSR occupy all of Poland and most of eastern Germany. The Soviets gained recognition of their pre-1941 annexations of Polish territory; as compensation, substantial portions of eastern Germany were ceded to Poland, whose borders were significantly shifted westwards.Piotr Eberhardt,

http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Pages 32–34

Treatment of Polish citizens under German occupation

''Generalplan Ost'', ''Lebensraum'' and expulsion of Poles

For months prior to the beginning ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1939, German newspapers and leaders had carried out a national and international propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

campaign accusing Polish authorities of organizing or tolerating violent ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

of ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

living in Poland. British ambassador Sir H. Kennard sent four statements in August 1939 to Viscount Halifax

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

regarding Hitler's claims about the treatment Germans were receiving in Poland; he came to the conclusion all the claims by Hitler and the Nazis were exaggerations or false claims.

From the beginning, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany was intended as fulfilment of the future plan of the German Reich described by

From the beginning, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany was intended as fulfilment of the future plan of the German Reich described by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

in his book ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Ge ...

'' as ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

'' ("living space") for the Germans in Central and Eastern Europe. The goal of the occupation was to turn the former territory of Poland into ethnically German "living space", by deporting and exterminating the non-German population, or relegating it to the status of slave laborers.

The goal of the German state under Nazi leadership during the war was the complete destruction of the Polish people and nation. The fate of the Polish people, as well as the fate of many other Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, was outlined in genocidal ''Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be under ...

'' (General Plan for the East) and a closely related ''Generalsiedlungsplan'' (General Plan for Settlement). Over a period of 30 years, approximately 12.5 million Germans would be resettled in the Slavic areas, including Poland; with some versions of the plan requiring the resettlement of at least 100 million Germans over a century. The Slavic inhabitants of those lands would be eliminated as the result of genocidal policies; and the survivors would be resettled further east, in less hospitable areas of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

, beyond the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

, such as Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

. At the plan's fulfillment, no Slavs or Jews would remain in Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europ ...

. ''Generalplan Ost'', essentially a grand plan to commit ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

, was divided into two parts, the ''Kleine Planung'' ("Small Plan"), covered actions which would be undertaken during the war, and the ''Grosse Planung'' ("Big Plan"), covered actions which would be undertaken after the war was won. The plan envisaged that different percentages of the various conquered nations would undergo Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

, be expelled and deported to the depths of Russia, and suffer other gruesome fates, including purposeful starvation and murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

, the net effect of which would ensure that the conquered territories would take on an irrevocably German character. Over a longer period of time, only about 3–4 million Poles, all of whom were considered suitable for Germanization, would be allowed to reside in the former territory of Poland.

Those plans began to be implemented almost immediately after German troops took control of Poland. As early as October 1939, many Poles were expelled from the annexed lands in order to make room for German colonizers. Only those Poles who had been selected for

Those plans began to be implemented almost immediately after German troops took control of Poland. As early as October 1939, many Poles were expelled from the annexed lands in order to make room for German colonizers. Only those Poles who had been selected for Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

, approximately 1.7 million including thousands of children who had been taken from their parents, were permitted to remain, and if they resisted it, they were to be sent to concentration camps, because "German blood must not be utilized in the interest of a foreign nation". By the end of 1940, at least 325,000 Poles from annexed lands were forced to abandon most of their property and forcibly resettled in the General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

. There were numerous fatalities among the very young and very old, many of whom either perished ''en route'' or perished in makeshift transit camps such as those in the towns of Potulice, Smukal, and Toruń

)''

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_flag = POL Toruń flag.svg

, image_shield = POL Toruń COA.svg

, nickname = City of Angels, Gingerbread city, Copernicus Town

, pushpin_map = Kuyavian-Pom ...

. The expulsions continued in 1941, with another 45,000 Poles forced to move eastwards, but following the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, the expulsions slowed down, as more and more trains were diverted for military logistics, rather than being made available for population transfers. Nonetheless, in late 1942 and 1943, large-scale expulsions also took place in the General Government, affecting at least 110,000 Poles in the Zamość

Zamość (; yi, זאמאשטש, Zamoshtsh; la, Zamoscia) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

...

–Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

region. Tens of thousands of the expelled, with no place to go, were simply imprisoned in the Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

(Oświęcim) and Majdanek concentration camp

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, ...

s. By 1942, the number of new German arrivals in pre-war Poland had already reached two million.William J. Duiker, Jackson J. Spielvogel, ''World History'', 1997. Page 794: By 1942, two million ethnic Germans had been settled in Poland.

The Nazi plans also called for Poland's 3.3 million Jews to be exterminated; the non-Jewish majority's extermination was planned for the long term and initiated through the mass murder of its political, religious, and intellectual elites at first, which was meant to make the formation of any organized top-down resistance more difficult. Further, the populace of occupied territories was to be relegated to the role of an unskilled labour-force for German-controlled industry and agriculture.Chapter XIII – Germanization and Spoliation" This was in spite of racial theory that falsely regarded most Polish leaders as actually being of "German blood",Richard C. Lukas,

', 1939–1945. Hippocrene Books, New York, 2001. and partly because of it, on the grounds that German blood must not be used in the service of a foreign nation. After Germany lost the war, the

International Military Tribunal

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

at the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

and Poland's Supreme National Tribunal

The Supreme National Tribunal ( pl, Najwyższy Trybunał Narodowy TN}) was a war-crime tribunal active in communist-era Poland from 1946 to 1948. Its aims and purpose were defined by the State National Council in decrees of 22 January and 17 Oc ...

concluded that the aim of German policies in Poland – the extermination of Poles and Jews – had "all the characteristics of genocide in the biological meaning of this term."

German People's List

The German People's List (''

The German People's List (''Deutsche Volksliste

The Deutsche Volksliste (German People's List), a Nazi Party institution, aimed to classify inhabitants of Nazi-occupied territories (1939-1945) into categories of desirability according to criteria systematised by ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich H ...

'') classified the ''willing'' Polish citizens into four groups of people with ethnic Germanic heritage. Group 1 included so-called ethnic Germans who had taken an active part in the struggle for the Germanization of Poland. Group 2 included those ethnic Germans who had not taken such an active part, but had "preserved" their German characteristics. Group 3 included individuals of alleged German stock who had become "Polonized", but whom it was believed, could be won back to Germany. This group also included persons of non-German descent married to Germans or members of non-Polish groups who were considered desirable for their political attitude and racial characteristics. Group 4 consisted of persons of German stock who had become politically merged with the Poles.

After registration in the List, individuals from Groups 1 and 2 automatically became German citizens. Those from Group 3 acquired German citizenship subject to revocation. Those from Group 4 received German citizenship through naturalization proceedings; resistance to Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

constituted treason because "German blood must not be utilized in the interest of a foreign nation," and such people were sent to concentration camps. Persons ineligible for the List were classified as stateless, and all Poles from the occupied territory, that is from the Government General of Poland, as distinct from the incorporated territory, were classified as non-protected.

Encouraging ethnic strife

According to the 1931 Polish census, out of a prewar population of 35 million, 66% spoke thePolish language

Polish (Polish: ''język polski'', , ''polszczyzna'' or simply ''polski'', ) is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group written in the Latin script. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles. In ad ...

as their mother tongue, and most of the Polish native speakers were Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

s. With regards to the remainder, 15% were Ukrainians, 8.5% Jews, 4.7% Belarusians, and 2.2% Germans.''Powszechny Spis Ludnosci r. 1921'' Germans intended to exploit the fact that the Second Polish Republic was an ethnically diverse territory, and their policy aimed to " divide and conquer" the ethnically diverse population of the occupied Polish territory, to prevent any unified resistance from forming. One of the attempts to divide the Polish nation was a creation of a new ethnicity called " Goralenvolk". Some minorities, like Kashubians

The Kashubians ( csb, Kaszëbi; pl, Kaszubi; german: Kaschuben), also known as Cassubians or Kashubs, are a Lechitic ( West Slavic) ethnic group native to the historical region of Pomerania, including its eastern part called Pomerelia, in nor ...

, were forcefully enrolled of into the Deutsche Volksliste

The Deutsche Volksliste (German People's List), a Nazi Party institution, aimed to classify inhabitants of Nazi-occupied territories (1939-1945) into categories of desirability according to criteria systematised by ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich H ...

, as a measure to compensate for the losses in the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

(unlike Poles, Deutsche Volksliste members were eligible for military conscription).

In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated 25 May 1940,

In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated 25 May 1940, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, head of the SS, wrote: "We need to divide the East's different ethnic groups up into as many parts and splinter groups as possible".See: Helmut Heiber, "Denkschrift Himmler Uber die Behandlung der Fremdvolkischen im Osten", ''Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte'' 1957, No. 2. (In)

Forced labour

Almost immediately after the invasion, Germans began forcibly conscripting laborers. Jews were drafted to repair war damage as early as October, with women and children 12 or older required to work; shifts could take half a day and with little compensation. The labourers, Jews, Poles and others, were employed in SS-owned enterprises (such as the German Armament Works, Deutsche Ausrustungswerke, DAW), but also in many private German firms – such asMesserschmitt

Messerschmitt AG () was a German share-ownership limited, aircraft manufacturing corporation named after its chief designer Willy Messerschmitt from mid-July 1938 onwards, and known primarily for its World War II fighter aircraft, in parti ...

, Junkers

Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (JFM, earlier JCO or JKO in World War I, English: Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works) more commonly Junkers , was a major German aircraft and aircraft engine manufacturer. It was founded there in Dessau, Ge ...

, Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', ''E ...

, and IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies— BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agf ...

.

Forced labourers were subject to harsh discriminatory measures. Announced on 8 March 1940 was the Polish decrees

Polish decrees, Polish directives or decrees on Poles (german: Polen-Erlasse, Polenerlasse) were the decrees of the Nazi Germany government announced on 8 March 1940 during World War II to regulate the working and living conditions of the Polis ...

which were used as a legal basis for foreign labourers in Germany.Ulrich Herbert, William Templer, ''Hitler's foreign workers: enforced foreign labor in Germany under the Third Reich'', Cambridge University Press, 1997,Google Print, p.71-73

The decrees required Poles to wear identifying purple P's on their clothing, made them subject to a curfew, and banned them from using public transportation as well as many German "cultural life" centres and "places of amusement" (this included churches and restaurants). Sexual relations between Germans and Poles were forbidden as ''

Rassenschande

''Rassenschande'' (, "racial shame") or ''Blutschande'' ( "blood disgrace") was an anti-miscegenation concept in Nazi German racial policy, pertaining to sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans. It was put into practice by policies like ...

'' (race defilement) under penalty of death. To keep them segregated from the German population, they were often housed in segregated barracks behind barbed wire.

Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stalingrád, label=none; ) ...

in 1942–1943. This led to the increased use of prisoners as forced labourers in German industries. Following the German invasion and occupation of Polish territory, at least 1.5 million Polish citizens, including teenagers, became labourers in Germany, few by choice. Historian Jan Gross estimates that "no more than 15 per cent" of Polish workers volunteered to go to work in Germany. A total of 2.3 million Polish citizens, including 300,000 POWs, were deported to Germany as forced laborers. They tended to have to work longer hours for lower wages than their German counterparts.

Concentration and extermination camps

A network of

A network of Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

were established on German-controlled territories, many of them in occupied Poland, including one of the largest and most infamous, Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

(Oświęcim). Those camps were officially designed as labor camps, and many displayed the motto '' Arbeit macht frei'' ("Work brings freedom"). Only high-ranking officials knew that one of the purposes of some of the camps, known as extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

(or death camps), was mass murder of the undesirable minorities; officially the prisoners were used in enterprises such as production of synthetic rubber

A synthetic rubber is an artificial elastomer. They are polymers synthesized from petroleum byproducts. About 32-million metric tons of rubbers are produced annually in the United States, and of that amount two thirds are synthetic. Synthetic rubb ...

, as was the case of a plant owned by IG Farben, whose laborers came from Auschwitz III camp, or Monowitz

Monowitz (also known as Monowitz-Buna, Buna and Auschwitz III) was a Nazi concentration camp and labor camp (''Arbeitslager'') run by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland from 1942–1945, during World War II and the Holocaust. For most of its exist ...

. Laborers from concentration camps were literally worked to death. in what was known as extermination through labor

Extermination through labour (or "extermination through work", german: Vernichtung durch Arbeit) is a term that was adopted to describe forced labor in Nazi concentration camps in light of the high mortality rate and poor conditions; in some ...

.

Auschwitz received the first contingent of 728 Poles on 14 June 1940, transferred from an overcrowded prison at Tarnów

Tarnów () is a city in southeastern Poland with 105,922 inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of 269,000 inhabitants. The city is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999. From 1975 to 1998, it was the capital of the Tarn� ...

. Within a year the Polish inmate population was in thousands, and begun to be exterminated, including in the first gassing experiment in September 1941. According to Polish historian Franciszek Piper, approximately 140,000–150,000 Poles went through Auschwitz, with about half of them perishing there due to executions, medical experiments, or due to starvation and disease. About 100,000 Poles were imprisoned in Majdanek camp, with similar fatality rate. About 30,000 Poles died at Mauthausen

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town of Mauthausen, Upper Austria, Mauthausen (roughly east of Linz), Upper Austria. It was the main camp of a group with List of subcamps of Mauthausen, nearly 100 further ...

, 20,000 at Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners ...

and Gross-Rosen each, 17,000 at Neuengamme and Ravensbrueck each, 10,000 at Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

, and tens of thousands perished in other camps and prisons.

The Holocaust

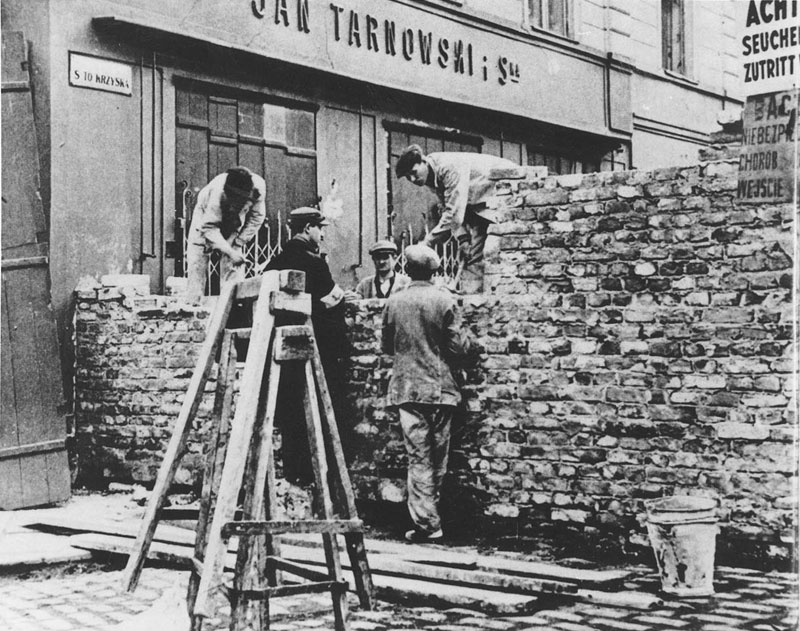

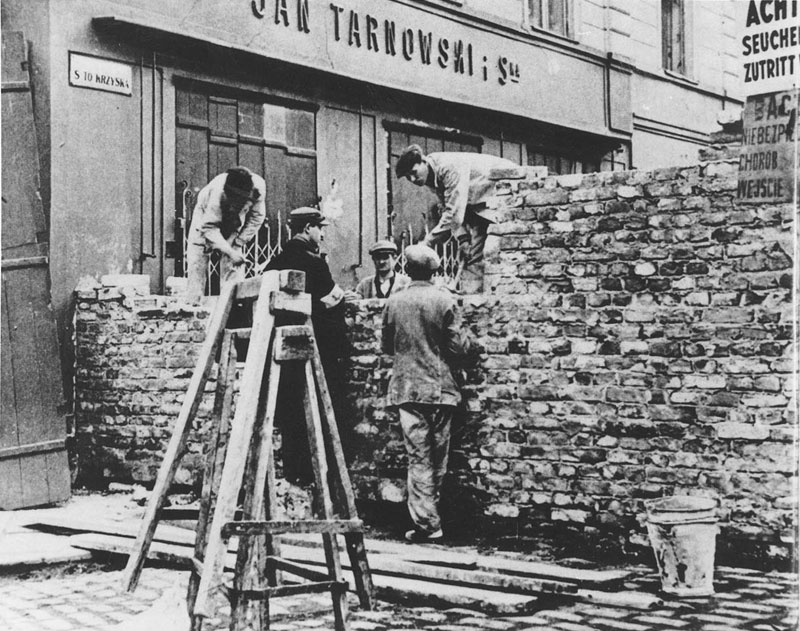

Following the

Following the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

in 1939 most of the approximately 3.5 million Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

were rounded up and put into newly established ghettos by Nazi Germany. The ghetto system was unsustainable, as by the end of 1941 the Jews had no savings left to pay the ''SS'' for food deliveries and no chance to earn their own keep. At 20 January 1942 Wannsee Conference, held near Berlin, new plans were outlined for the total genocide of the Jews, known as the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national ...

". The extermination program was codenamed Operation Reinhard

or ''Einsatz Reinhard''

, location = Occupied Poland

, date = October 1941 – November 1943

, incident_type = Mass deportations to extermination camps

, perpetrators = Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erwin L ...

.

Three secret extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s set up specifically for Operation Reinhard; Treblinka

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The cam ...

, Belzec and Sobibor. In addition to the Reinhard camps, mass killing facilities such as gas chamber

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

History

...

s using Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

were added to the Majdanek concentration camp

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, ...

in March 1942 and at Auschwitz and Chełmno

Chełmno (; older en, Culm; formerly ) is a town in northern Poland near the Vistula river with 18,915 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is the seat of the Chełmno County in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Due to its regional impor ...

.

Cultural genocide

Nazi Germany engaged in a concentrated effort to destroy Polish culture. To that end, numerous cultural and educational institutions were closed or destroyed, from schools and universities, through monuments and libraries, to laboratories and museums. Many employees of said institutions were arrested and executed as part wider persecutions of Polish intellectual elite. Schooling of Polish children was curtailed to a few years of elementary education, as outlined by Himmler's May 1940 memorandum: "The sole goal of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, nothing above the number 500; writing one's name; and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans. ... I do not think that reading is desirable".See alsoPoles: Victims of the Nazi Era

Extermination of elites

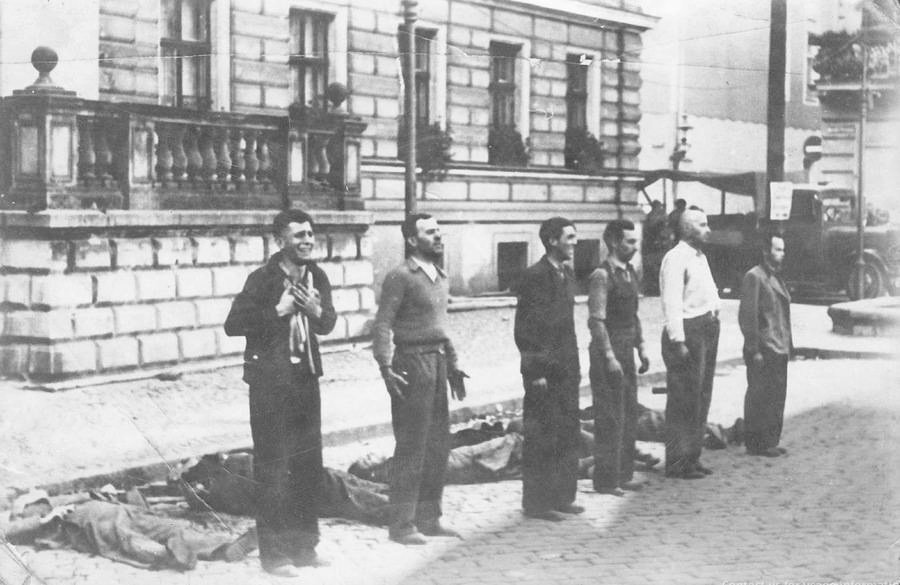

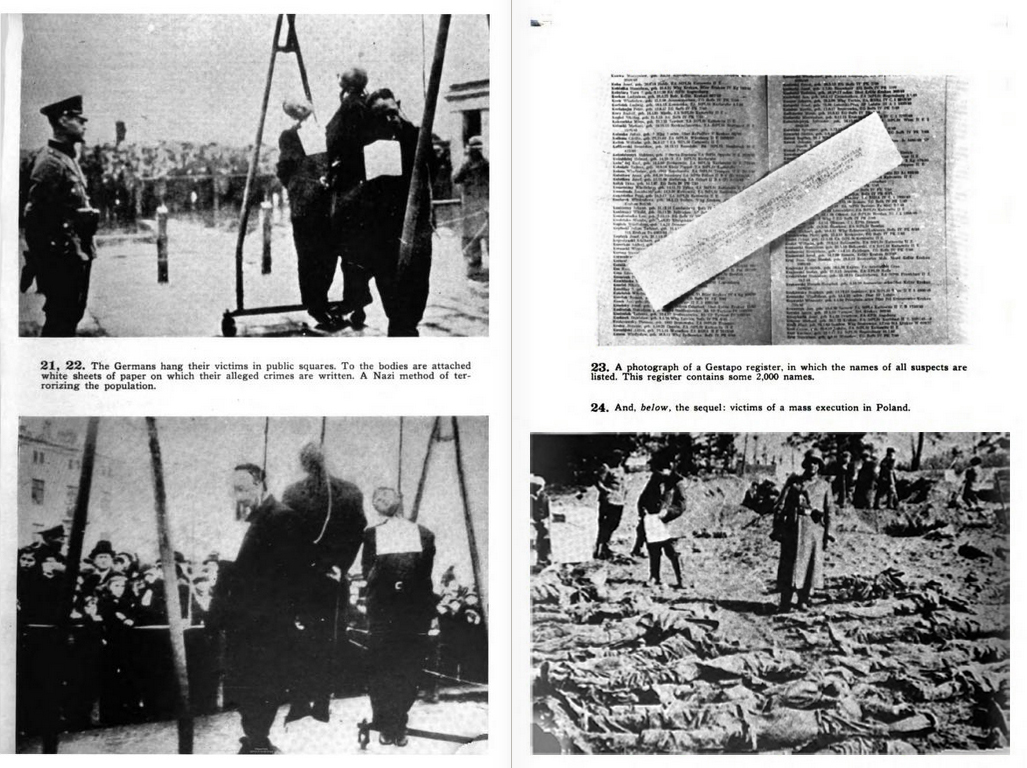

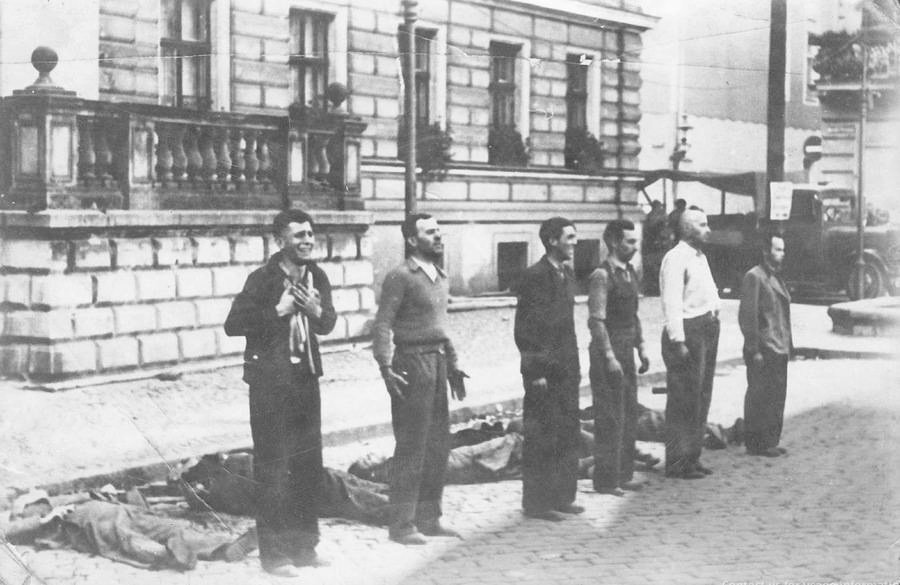

The extermination of the Polish elite was the first stage of the Nazis' plan to destroy the Polish nation and its culture. The disappearance of the Poles' leadership was seen as necessary to the establishment of the Germans as the Poles' sole leaders. Proscription lists ('' Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen''), prepared before the war started, identified more than 61,000 members of the Polish elite and

The extermination of the Polish elite was the first stage of the Nazis' plan to destroy the Polish nation and its culture. The disappearance of the Poles' leadership was seen as necessary to the establishment of the Germans as the Poles' sole leaders. Proscription lists ('' Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen''), prepared before the war started, identified more than 61,000 members of the Polish elite and intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

leaders who were deemed unfriendly to Germany.Piotr Eberhardt, http://rcin.org.pl/Content/15652/WA51_13607_r2011-nr12_Monografie.pdf Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950)

', Polish Academy of Sciences Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Monographies, 12. Page 46 Already during the 1939 German invasion, dedicated units of SS and police (the ''

Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

'') were tasked with arresting or outright killing of those resisting the Germans.

They were aided by some regular German army units and "self-defense" forces composed of members of German minority in Poland

The registered German minority in Poland at the 2011 national census consisted of 148,000 people, of whom 64,000 declared both German and Polish ethnicities and 45,000 solely German ethnicity.Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyni ...

, the Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of ''volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sing ...

. The Nazi regime

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's policy of murdering or suppressing the ethnic Polish elites was known as Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg (german: Unternehmen Tannenberg) was a codename for one of the anti-Polish extermination actions by Nazi Germany that were directed at the Poles during the opening stages of World War II in Europe, as part of the '' Generalp ...

. This included not only those resisting actively, but also those simply capable of doing so by the virtue of their social status

Social status is the level of social value a person is considered to possess. More specifically, it refers to the relative level of respect, honour, assumed competence, and deference accorded to people, groups, and organizations in a society. St ...

. As a result, tens of thousands of people found "guilty" of being educated (members of the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, from clergymen to government officials, doctors, teachers and journalists) or wealthy (landowners, business owners, and so on) were either executed on spot, sometimes in mass executions, or imprisoned, some destined for the concentration camps. Some of the mass executions were reprisal actions for actions of the Polish resistance, with German officials adhering to the collective guilt principle and holding entire communities responsible for the actions of unidentified perpetrators.

One of the most infamous German operations was the '' Außerordentliche Befriedungsaktion'' (''AB-Aktion'' in short, German for ''Special Pacification''), a German campaign during World War II aimed at Polish leaders and the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, including many university professors, teachers and priests. In the spring and summer of 1940, more than 30,000 Poles were arrested by the German authorities of German-occupied Poland

German-occupied Poland during World War II consisted of two major parts with different types of administration.

The Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II—nearly a quarter of the ...

. Several thousands were executed outside Warsaw, in the Kampinos

Kampinos is a village in Warsaw West County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Kampinos. It lies approximately east of Sochaczew and west of Warsaw.

The village li ...

forest near Palmiry, and inside the city at the Pawiak

Pawiak () was a prison built in 1835 in Warsaw, Congress Poland.

During the January 1863 Uprising, it served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia.

During the World War II German occupation o ...

prison. Most of the remainder were sent to various German concentration camps. Mass arrests and shootings of Polish intellectuals and academics included Sonderaktion Krakau

''Sonderaktion Krakau'' was a German operation against professors and academics of the Jagiellonian University and other universities in German-occupied Kraków, Poland, at the beginning of World War II. It was carried out as part of the much bro ...

and the massacre of Lwów professors

In July 1941, 25 Polish academics from the city of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine) along with the 25 of their family members were killed by Nazi German occupation forces. By targeting prominent citizens and intellectuals for elimination, the Nazis ho ...

.

The Nazis also persecuted the Catholic Church in Poland and other, smaller religions.

Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where they set about systematically dismantling the Church – arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen and nuns were murdered or sent to concentration and labor camps. Already in 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. Primate of Poland, Cardinal August Hlond, submitted an official account of the persecutions of the Polish Church to the Vatican.The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942; pp. 34–51 In his final observations for

The Nazis also persecuted the Catholic Church in Poland and other, smaller religions.

Nazi policy towards the Church was at its most severe in the territories it annexed to Greater Germany, where they set about systematically dismantling the Church – arresting its leaders, exiling its clergymen, closing its churches, monasteries and convents. Many clergymen and nuns were murdered or sent to concentration and labor camps. Already in 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. Primate of Poland, Cardinal August Hlond, submitted an official account of the persecutions of the Polish Church to the Vatican.The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942; pp. 34–51 In his final observations for Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, Hlond wrote: "Hitlerism aims at the systematic and total destruction of the Catholic Church in the... territories of Poland which have been incorporated into the Reich...". The smaller Evangelical churches of Poland also suffered. The entirety of the Protestant clergy of the Cieszyn region of Silesia were arrested and deported to concentration camps at Mauthausen, Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or sus ...

, Dachau and Oranienburg

Oranienburg () is a town in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Oberhavel.

Geography

Oranienburg is a town located on the banks of the Havel river, 35 km north of the centre of Berlin.

Division of the town

Oranienburg ...

. Protestant clergy leaders who perished in those purges included charity activist Karol Kulisz, theology professor Edmund Bursche, and Bishop of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Poland

The Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in the Republic of Poland ( pl, Kościół Ewangelicko-Augsburski w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) is a Lutheran denomination and the largest Protestant body in Poland with about 61,000 members and ...

, Juliusz Bursche

Juliusz Bursche (September 19, 1862 in Kalisz – February 20, 1942?) was a bishop of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland. A vocal opponent of Nazi Germany, after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, he was arrested by the Germans, ...

.

Germanization

In the territories annexed to Nazi Germany, in particular with regards to the westernmost incorporated territories—the so-calledWartheland

The ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (initially ''Reichsgau Posen'', also: ''Warthegau'') was a Nazi German ''Reichsgau'' formed from parts of Polish territory annexed in 1939 during World War II. It comprised the region of Greater Poland and adjacent ...

— the Nazis aimed for a complete "Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

", i.e. full cultural, political, economic and social assimilation. The Polish language was forbidden to be taught even in elementary schools; landmarks from streets to cities were renamed ''en masse'' (Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of ca ...

became Litzmannstadt, and so on). All manner of Polish enterprises, up to small shops, were taken over, with prior owners rarely compensated. Signs posted in public places prohibited non-Germans from entering these places warning: "Entrance is forbidden to Poles, Jews, and dogs.", or ''Nur für Deutsche

The slogan ''Nur für Deutsche'' (English: "Only for Germans") was a German ethnocentric slogan indicating that certain establishments, transportation and other facilities such as park benches, bars and restaurants were reserved exclusively f ...

'' ("Only for Germans"), commonly found on many public utilities and places such as trams, parks, cafes, cinemas, theaters, and others.

The Nazis kept an eye out for Polish children who possessed Nordic racial characteristics. An estimated total of 50,000 children, majority taken from orphanages and foster homes in the annexed lands, but some separated from their parents, were taken into a special Germanization program.''Nazi Conspiracy & Aggression Volume I Chapter XIII Germanization & Spoliation''Polish women deported to Germany as forced labourers and who bore children were a common victim of this policy, with their infants regularly taken. If the child passed the battery of racial, physical and psychological tests, they were sent on to Germany for "Germanization". At least 4,454 children were given new German names, forbidden to use Polish language, and reeducated in Nazi institutions. Few were ever reunited with their original families. Those deemed as unsuitable for Germanization for being "not

Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

enough" were sent to orphanages or even to concentration camps like Auschwitz, where many perished, often killed by intercardiac injections of phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it r ...

. For Polish forced laborers, in some cases if an examination of the parents suggested that the child might not be "racially valuable", the mother was compelled to have an abortion. Infants who did not pass muster would be removed to a state orphanage (Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätte

During World War II, Nazi birthing centres for foreign workers, known in German as ' (literally "foreign children nurseries"), ' ("eastern worker children nurseries"), or ''Säuglingsheim'' ("baby home") were German institutions used as stations ...

), where many died from the lack of food.

Resistance

Despite the military defeat of the Polish Army in September 1939, the Polish government itself never surrendered, instead evacuating West, where it formed the

Despite the military defeat of the Polish Army in September 1939, the Polish government itself never surrendered, instead evacuating West, where it formed the Polish government in Exile