Nuclear weapons debate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of

Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past

''UNLV FUSION'', 2005, p. 20. and nuclear weapons have been detonated on over two thousand occasions for

A World Free of Nuclear Weapons

''Wall Street Journal'', January 4, 2007, page A15. A 2011 article in ''

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

. Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

were divided over the use of the weapon. The only time nuclear weapons have been used in warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regu ...

was during the final stages of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

when USAAF

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 ...

bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an aircra ...

dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

and Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

in early August 1945. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

and the U.S.'s ethical

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

justification for them have been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades.

Nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

refers both to the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world. Proponents of disarmament typically condemn a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ex ...

the threat or use of nuclear weapons as immoral and argue that only total disarmament can eliminate the possibility of nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine deterrence and make conventional wars more likely, more destructive, or both. The debate becomes considerably complex when considering various scenarios for example, total vs partial or unilateral

__NOTOC__

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Such action may be in disregard for other parties, or as an expression of a commitment toward a direction which other parties may find disagreeable. As a word, ''un ...

vs multilateral disarmament.

Nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

is a related concern, which most commonly refers to the spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries and increases the risks of nuclear war arising from regional conflicts. The diffusion of nuclear technologies -- especially the nuclear fuel cycle technologies for producing weapons-usable nuclear materials such as highly enriched uranium and plutonium -- contributes to the risk of nuclear proliferation. These forms of proliferation are sometimes referred to as horizontal proliferation to distinguish them from vertical proliferation, the expansion of nuclear stockpiles of established nuclear powers.

History

Manhattan Project

Because the Manhattan Project was considered to be "top secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kn ...

," there was no public discussion of the use of nuclear arms, and even within the US government, knowledge of the bomb was extremely limited. However, even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

were divided over the use of the weapon.

Franck Report

On June 2nd 1945,Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

, the leader of the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

, also known as Met Lab, at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

briefed his staff on the latest information from the Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on m ...

, which was formulating plans for the use of the atomic bomb to force Japanese capitulation. In response to the briefing, Met Lab's Committee on the Social and Political Implications of the Atomic Bomb, chaired by James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate i ...

, wrote the Franck Report

The Franck Report of June 1945 was a document signed by several prominent nuclear physicists recommending that the United States not use the atomic bomb as a weapon to prompt the surrender of Japan in World War II.

The report was named for James ...

. The report, to which Leo Szilárd

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

and Glenn T. Seaborg also contributed, argued that instead of being used against a city, the first atomic bomb should be "demonstrated" to the Japanese on an uninhabited area. The recommendation was not agreed with by the military commanders, the Los Alamos Target Committee (made up of other scientists), or the politicians who had input into the use of the weapon.

The report also argued that to preclude a nuclear arms race and a destabilized world order, the existence of the weapon should be made public so that a collaborative, international body could come to control atomic power:"From this point of view a demonstration of the new weapon may best be made before the eyes of representatives of all United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America would be able to say to the world, “You see what weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future and to join other nations in working out adequate supervision of the use of this nuclear weapon.” - The Franck Report

Szilárd Petition

70 scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, many of them from Met Lab, represented in part byLeó Szilárd

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

, put forth a petition to President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

in July 1945. The Szilárd Petition

The Szilárd petition, drafted and circulated in July 1945 by scientist Leo Szilard, was signed by 70 scientists working on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. It asked President H ...

urged Truman to use the atomic bomb only if the full terms of surrender were made public and if Japan, in full possession of the facts, still refused to surrender. "We, the undersigned, respectfully petition: first, that you exercise your power as Commander-in-Chief, to rule that the United States shall not resort to the use of atomic bombs in this war unless the terms which will be imposed upon Japan have been made public in detail and Japan knowing these terms has refused to surrender; second, that in such an event the question whether or not to use atomic bombs be decided by you in the light of the considerations presented in this petition as well as all the other moral responsibilities which are involved." - The Szilárd PetitionThe petition also warned Truman to consider the future implications of the decision to use the atomic bomb, including the probability of a rapid

nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

and a decline in global security, and pleaded with him to prevent such an eventuality if possible.

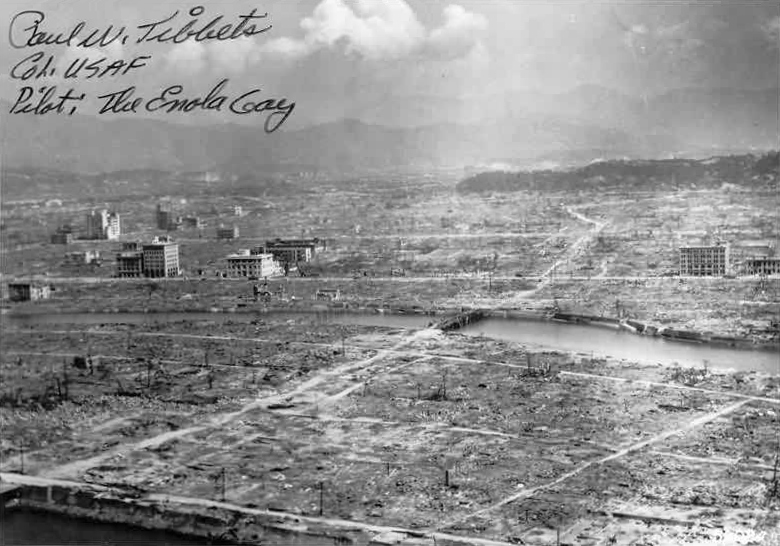

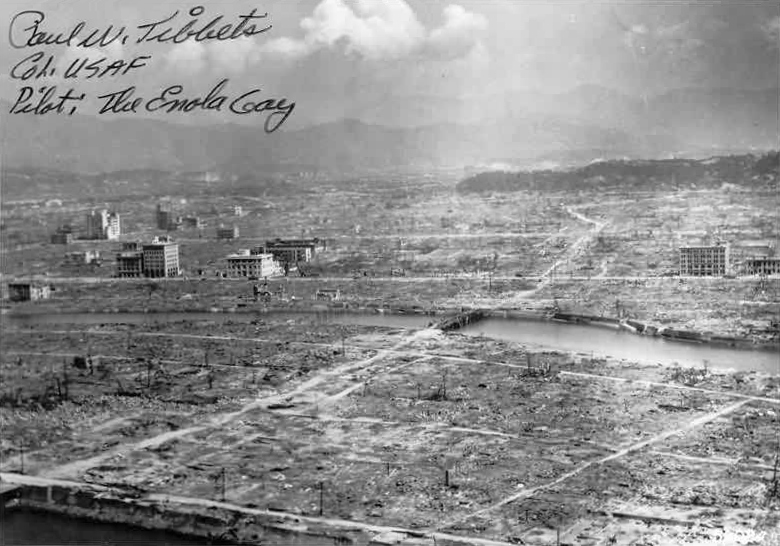

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

TheLittle Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

atomic bomb was detonated over the Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

ese city of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings (including the headquarters

Headquarters (commonly referred to as HQ) denotes the location where most, if not all, of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. In the United States, the corporate headquarters represents the entity at the center or the to ...

of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division) and killed approximately 75,000 people, among them 20,000 Japanese soldiers and 20,000 Koreans. Detonation of the "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" atomic bomb exploded over the Japanese city of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

three days later on 9 August 1945, destroying 60% of the city and killing approximately 35,000 people, among them 23,200-28,200 Japanese civilian munitions workers and 150 Japanese soldiers. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

and the U.S.'s ethical

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. J. Samuel Walker suggests that "the controversy over the use of the bomb seems certain to continue".

Postwar

After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew,Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew KirkRecollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past

''UNLV FUSION'', 2005, p. 20. and nuclear weapons have been detonated on over two thousand occasions for

testing

An examination (exam or evaluation) or test is an educational assessment intended to measure a test-taker's knowledge, skill, aptitude, physical fitness, or classification in many other topics (e.g., beliefs). A test may be administered verba ...

and demonstration purposes. Countries known to have detonated nuclear weapons and that acknowledge possessing such weapons are (chronologically) the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

(succeeded as a nuclear power by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

), the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

.

In the early 1980s, a revival of the nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

caused a popular nuclear disarmament movement to emerge. In October 1981 500,000 people took to the streets in several cities in Italy, more than 250,000 people protested in Bonn, 250,000 demonstrated in London, and 100,000 marched in Brussels. The largest anti-nuclear protest was held on June 12, 1982, when one million people demonstrated in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

against nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

. In October 1983, nearly 3 million people across western Europe protested nuclear missile deployments and demanded an end to the arms race.

Arguments

Under the scenario of total multilateral disarmament, there is no possibility ofnuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

. Under scenarios of partial disarmament, there is a disagreement as to how the probability of nuclear war would change. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine the ability of governments to threaten sufficient retaliation upon an attack to deter aggression against them. Application of game theory to questions of strategic nuclear warfare during the Cold War resulted in the doctrine of mutually assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

(MAD), a concept developed by Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the ...

and others in the mid-1960s. Its success in averting nuclear war was theorized to depend upon the "readiness at any time before, during, or after an attack to destroy the adversary as a functioning society." Those who believe governments that should develop or maintain nuclear-strike capability usually justify their position with reference to the Cold War, claiming that a " nuclear peace" was the result of both the US and the USSR possessing mutual second-strike retaliation capability. Since the end of the Cold War, theories of deterrence in international relations have been further developed and generalized in the concept of the stability–instability paradox Proponents of disarmament call into question the assumption that political leaders are rational actors who place the protection of their citizens above other considerations, and highlight, as McNamara himself later acknowledged with the benefit of hindsight, the non-rational choices, chance, and contingency, which played a significant role in averting nuclear war, such as during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and the Able Archer 83

Able Archer 83 was the annual NATO Able Archer exercise conducted in November 1983. The purpose for the command post exercise, like previous years, was to simulate a period of conflict escalation, culminating in the US military attaining a simul ...

crisis of 1983. Thus, they argue that evidence trumps theory and deterrence theories cannot be reconciled with the historical record.

Kenneth Waltz

Kenneth Neal Waltz (; June 8, 1924 – May 12, 2013) was an American political scientist who was a member of the faculty at both the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University and one of the most prominent scholars in the field of ...

argues in favor of the continued proliferation of nuclear weapons. In the July 2012 issue of '' Foreign Affairs'' Waltz took issue with the view of most US, European, and Israeli commentators and policymakers that a nuclear-armed Iran would be unacceptable. Instead, Waltz argues that it would probably be the best possible outcome by restoring stability to the Middle East since it would balance the Israeli regional monopoly on nuclear weapons. Professor John Mueller of Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

, author of ''Atomic Obsession'' has also dismissed the need to interfere with Iran's nuclear program and expressed that arms control measures are counterproductive. During a 2010 lecture at the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou, MU, or Missouri) is a public land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus University of Missouri System. MU was founded in ...

, which was broadcast by C-Span, Dr. Mueller also argued that the threat from nuclear weapons, including that from terrorists, has been exaggerated in the popular media and by officials.

In contrast, various American government officials, including Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, George Shultz, Sam Nunn

Samuel Augustus Nunn Jr. (born September 8, 1938) is an American politician who served as a United States Senator from Georgia (1972–1997) as a member of the Democratic Party.

After leaving Congress, Nunn co-founded the Nuclear Threat Initia ...

, and William Perry, who were in office during the Cold War period, now advocate the elimination of nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s in the belief that the doctrine of mutual Soviet-American deterrence is obsolete and that reliance on nuclear weapons for deterrence is increasingly hazardous and decreasingly effective ever since the Cold War ended.George P. Shultz, William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger and Sam Nunn.A World Free of Nuclear Weapons

''Wall Street Journal'', January 4, 2007, page A15. A 2011 article in ''

The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'' argued, along similar lines, that risks are more acute in rivalries between relatively-new nuclear states that lack the "security safeguards" developed by the Americans and the Soviets and that additional risks are posed by the emergence of pariah states, such as North Korea (possibly soon to be joined by Iran), armed with nuclear weapons as well as the declared ambition of terrorists to steal, buy, or build a nuclear device.

See also

*Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty to ban nuclear weapons test explosions and any other nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nati ...

* Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

*Global catastrophic risk

A global catastrophic risk or a doomsday scenario is a hypothetical future event that could damage human well-being on a global scale, even endangering or destroying modern civilization. An event that could cause human extinction or permanen ...

*List of nuclear weapons

This is a list of nuclear weapons listed according to country of origin, and then by type within the states.

United States

US nuclear weapons of all types – bombs, warheads, shells, and others – are numbered in the same sequence starting wi ...

* Nth Country Experiment

*''Nuclear Tipping Point

''Nuclear Tipping Point'' is a 2010 documentary film produced by the Nuclear Threat Initiative. It features interviews with four American government officials who were in office during the Cold War period, but are now advocating for the eliminatio ...

''

*Three Non-Nuclear Principles

Japan's are a parliamentary resolution (never adopted into law) that have guided Japanese nuclear policy since their inception in the late 1960s, and reflect general public sentiment and national policy since the end of World War II. The ten ...

, of Japan

* Uranium mining debate

References

Further reading

*M. Clarke and M. Mowlam (Eds) (1982). ''Debate on Disarmament'', Routledge and Kegan Paul. * Cooke, Stephanie (2009). '' In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age'', Black Inc. * Falk, Jim (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press. * Murphy, Arthur W. (1976). ''The Nuclear Power Controversy'', Prentice-Hall. * Malheiros, Tania. ''Brasiliens geheime Bombe: Das brasilianische Atomprogramm''. Tradução: Maria Conceição da Costa e Paulo Carvalho da Silva Filho. Frankfurt am Main: Report-Verlag, 1995. * Malheiros, Tania. ''Brasil, a bomba oculta: O programa nuclear brasileiro''. Rio de Janeiro: Gryphus, 1993. * Malheiros, Tania. ''Histórias Secretas do Brasil Nuclear''. (WVA Editora; ) *Walker, J. Samuel (2004). '' Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective'', University of California Press. *Williams, Phil (Ed.) (1984). ''The Nuclear Debate: Issues and Politics'', Routledge & Keagan Paul, London. * Wittner, Lawrence S. (2009). ''Confronting the Bomb: A Short History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement'', Stanford University Press. {{Nuclear and radiation accidents and incidents Nuclear history Nuclear technology