The following events occurred in November 1959:

November 1, 1959 (Sunday)

*In

Rwanda, violence between the

Hutu

The Hutu (), also known as the Abahutu, are a Bantu ethnic or social group which is native to the African Great Lakes region. They mainly live in Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where they form one of the p ...

and

Tutsi

The Tutsi (), or Abatutsi (), are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. They are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi (the other two being the largest Bantu ethnic ...

people was triggered by an attack upon Hutu activist

Dominique Mbonyumutwa. Over the next two weeks 300 people, mostly Tutsi, were killed, in what was known as the

wind of destruction.

*

John Howard Griffin

John Howard Griffin (June 16, 1920 – September 9, 1980) was an American journalist and author from Texas who wrote about and championed racial equality. He is best known for his 1959 project to temporarily pass as a black man and journey throug ...

, a white writer from

Mansfield, Texas

Mansfield is a suburban city in the U.S. state of Texas, and is part of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex area. The city is located mostly in Tarrant county, with small parts in Ellis and Johnson counties. Its location is approximately 30 mile ...

, began the process of making himself look black in order to research his classic book, ''

Black Like Me''.

*

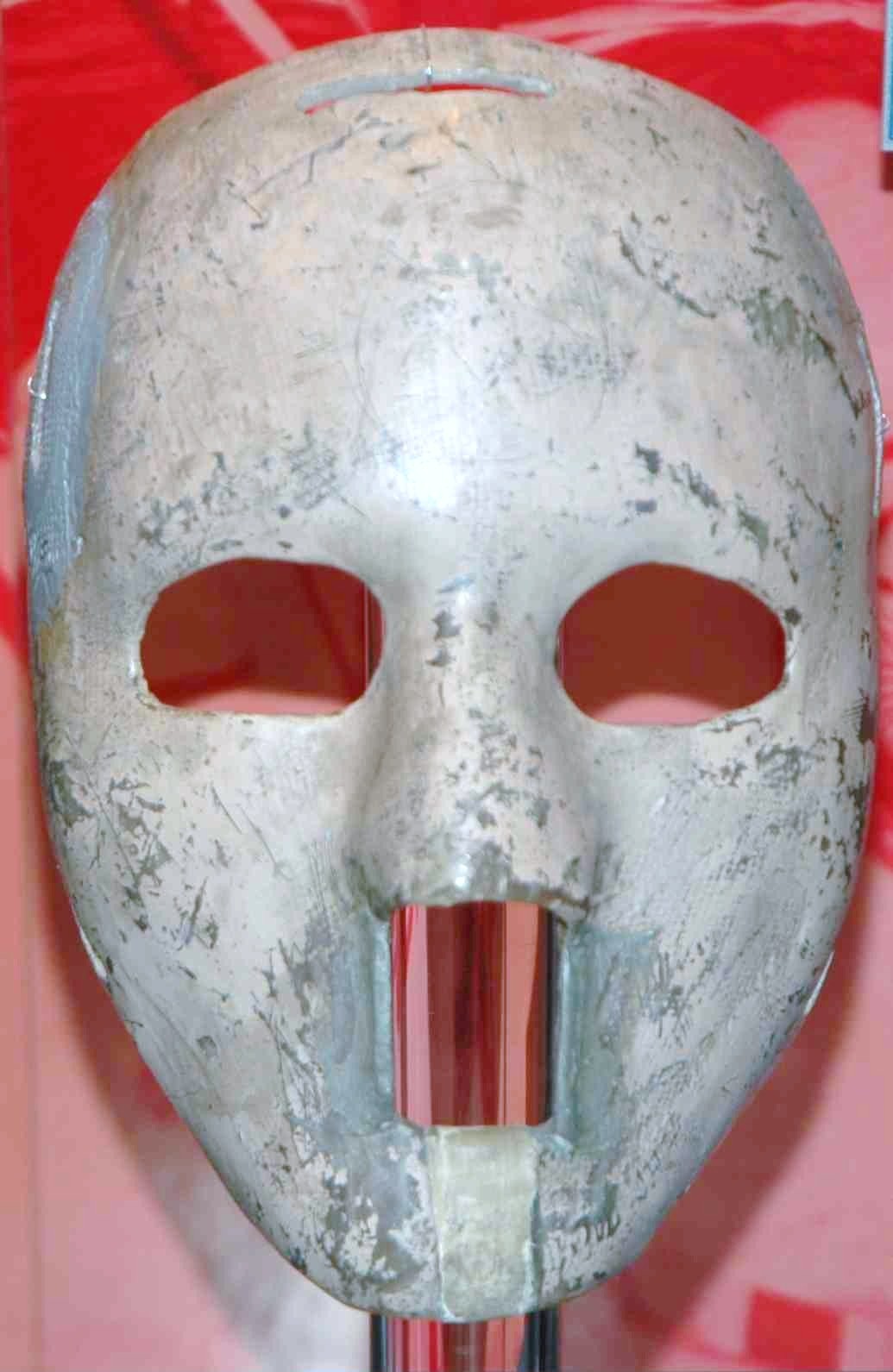

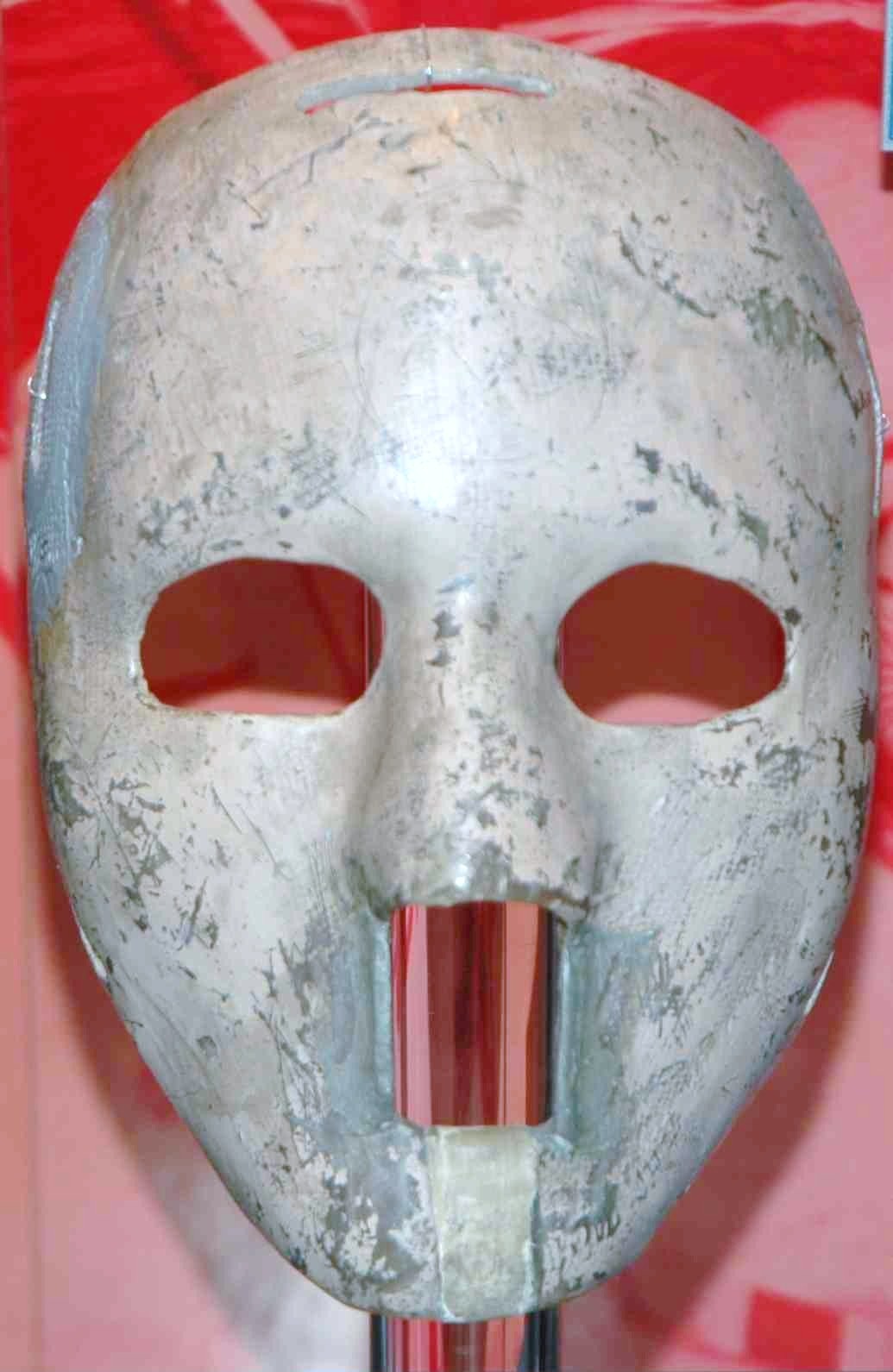

Jacques Plante

Joseph Jacques Omer Plante (; January 17, 1929 – February 27, 1986) was a Canadian professional ice hockey goaltender. During a career lasting from 1947 to 1975, he was considered to be one of the most important innovators in hockey. He played ...

of the

Montreal Canadiens

The Montreal CanadiensEven in English, the French spelling is always used instead of ''Canadians''. The French spelling of ''Montréal'' is also sometimes used in the English media. (french: link=no, Les Canadiens de Montréal), officially ...

became the first NHL goalie in modern times to wear a

face mask, donning it after a shot from

Andy Bathgate

Andrew James Bathgate (August 28, 1932 – February 26, 2016) was a Canadian professional ice hockey right wing who played 17 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for the New York Rangers, Toronto Maple Leafs, Detroit Red Wings and Pittsbu ...

(

New York Rangers

The New York Rangers are a professional ice hockey team based in the New York City borough of Manhattan. They compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Metropolitan Division in the Eastern Conference. The team plays its home ...

) struck him in the face. The Canadiens won 3–1. Soon, all goalies were wearing masks.

November 2, 1959 (Monday)

*

Charles Van Doren

Charles Lincoln Van Doren (February 12, 1926 – April 9, 2019) was an American writer and editor who was involved in a television quiz show scandal in the 1950s. In 1959 he testified before the U.S. Congress that he had been given the corr ...

, famous for being the all-time winner on the TV

game show

A game show is a genre of broadcast viewing entertainment (radio, television, internet, stage or other) where contestants compete for a reward. These programs can either be participatory or demonstrative and are typically directed by a host, ...

''Twenty One'', admitted in a hearing in Congress that he had been supplied the answers in advance.

*Born:

Saïd Aouita

Saïd Aouita ( ar, سعيد عويطة; born November 2, 1959) is a former Moroccan track and field athlete. He is the only athlete in history to have won a medal in each of the 800 meters and 5000 meters at the Olympic games. He won the 5000 mete ...

, Moroccan distance runner, 1987 world champion in the 5000 meter race and 1984 Olympic gold medalist; in

Kenitra

Kenitra ( ar, القُنَيْطَرَة, , , ; ber, ⵇⵏⵉⵟⵔⴰ, Qniṭra; french: Kénitra) is a city in north western Morocco, formerly known as Port Lyautey from 1932 to 1956. It is a port on the Sebou river, has a population in 201 ...

. Aouita at one time held the world record for fastest ever 1500 meters (1985-1992); 3000 meters (1989-1992) and 5000 meters (1985-1994)

November 3, 1959 (Tuesday)

*In

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative ...

for

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

's

Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

,

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

's

Mapai

Mapai ( he, מַפָּא"י, an acronym for , ''Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael'', lit. "Workers' Party of the Land of Israel") was a democratic socialist political party in Israel, and was the dominant force in Israeli politics until its merger in ...

Party retained power, capturing 47 of the 120 seats, but still 13 short of a majority.

*Speaking at France's

École Militaire

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savo ...

,

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Charles de Gaulle announced that France would build its own nuclear strike force, the "

force de frappe

The ''Force de frappe'' (French language, French: "strike force"), or ''Force de dissuasion'' ("deterrent force") after 1961,Gunston, Bill. Bombers of the West. New York: Charles Scribner's and Sons; 1973. p104 is the designation of what used to ...

", "whether we make it ourselves or buy it".

*Rioting broke out in

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

after a crowd of 2,000 students in

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

clashed with police at the American controlled

Panama Canal Zone.

November 4, 1959 (Wednesday)

*Six

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i jets and four

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

ian

MiG-17

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 (russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-17; NATO reporting name: Fresco) is a high-subsonic fighter aircraft produced in the Soviet Union from 1952 and was operated by air forces internationally. The MiG-17 w ...

s clashed in a dogfight near the border between the two nations. All planes reportedly returned safely and the battle did not lead to further action.

*The government of

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

imposed emergency measures after more than 6,700 people had been paralyzed by tainted

cooking oil, including the death penalty for manufacturers who had sold the oil in

Meknes

Meknes ( ar, مكناس, maknās, ; ber, ⴰⵎⴽⵏⴰⵙ, amknas; french: Meknès) is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco, located in northern central Morocco and the sixth largest city by population in the kingdom. Founded in the 11th c ...

during the feast of Ramadan in September and October. Peanut oil had been mixed with a jet aircraft engine rinse purchased as surplus from a United States Air Force base at

Nouasseur, and the victims were poisoned by

tricresyl phosphate

Tricresyl phosphate (TCP), is a mixture of three isomeric organophosphate compounds most notably used as a flame retardant and as a plasticizer in manufacturing for lacquers and varnishes and vinyl plastics. Pure tricresyl phosphate is a colourles ...

. More than 10,000 people eventually required treatment for injuries. Five of the manufacturers were sentenced to death, but never executed.

*

Little Joe 1A

Little Joe 1A (LJ-1A) was an unmanned rocket launched as part of NASA's Mercury program on November 4, 1959. This flight, a repeat of the Little Joe 1 (LJ-1) launch, was to test a launch abort under high aerodynamic load conditions. After lift-of ...

was launched in a test for a planned abort under high aerodynamic load conditions. This flight was a repeat of the failed

Little Joe 1 launch that had been planned for August 21, 1959. After lift-off, the pressure sensing system was to supply a signal when the intended abort dynamic pressure was reached (about 30 seconds after launch). An electrical impulse was then sent to the explosive bolts to separate the spacecraft from the launch vehicle. Up to this point, the operation went as planned, but the impulse was also designed to start the igniter in the escape motor. The igniter activated, but pressure failed to build up in the motor until a number of seconds had elapsed. Thus, the abort maneuver, the prime mission of the flight, was accomplished at a dynamic pressure that was too low. For this reason, a repeat of the test was planned. All other events from the launch through recovery occurred without incident. The flight attained an altitude of 9 statute miles, a range of 11.5 statute miles, and a speed of .

[ ]

*Died:

**

U.S. Congressman Charles A. Boyle of

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

, 52, was killed in an automobile accident as he returned from a long day of campaigning on behalf of Chicago Democrats.

**U.S. Congressman

Steven V. Carter of

Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

, 44, died the same day of cancer.

November 5, 1959 (Thursday)

*The

Mercury astronauts were fitted with

pressure suit

A pressure suit is a protective suit worn by high-altitude pilots who may fly at altitudes where the air pressure is too low for an unprotected person to survive, even breathing pure oxygen at positive pressure. Such suits may be either full-pr ...

s and indoctrinated as to their use at the

B. F. Goodrich Company,

Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 Census, the city prop ...

.

*Test pilot

Albert Scott Crossfield

Albert Scott Crossfield (October 2, 1921 – April 19, 2006) was an American naval officer and test pilot. In 1953, he became the first pilot to fly at twice the speed of sound. Crossfield was the first of twelve pilots who flew the North Ameri ...

encountered trouble at on the third flight of the

North American X-15 rocket plane and was unable to jettison his fuel because of a steep glide. The plane buckled on a hard landing on a dry lake bed. By chance, the split occurred between the cabin and the fuel tanks, and the fuel did not ignite.

*Born:

Bryan Adams

Bryan Guy Adams (born 5 November 1959) is a Canadian musician, singer, songwriter, composer, and photographer. He has been cited as one of the best-selling music artists of all time, and is estimated to have sold between 75 million and mor ...

, Canadian pop singer, in

Kingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north-eastern end of Lake Ontario, at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River (south end of the Rideau Canal). The city is midway between To ...

November 6, 1959 (Friday)

*In

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Dr.

Bernard Lown

Bernard Lown (June 7, 1921February 16, 2021) was a Lithuanian-American cardiologist and inventor. Lown was the original developer of the direct current defibrillator for cardiac resuscitation, and the cardioverter for correcting rapid disordered ...

was inspired to create the direct current heart

defibrillator

Defibrillation is a treatment for life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, specifically ventricular fibrillation (V-Fib) and non-perfusing ventricular tachycardia (V-Tach). A defibrillator delivers a dose of electric current (often called a ''coun ...

after using 400 volts of electricity to restore the heart rhythm of a patient, known to history only as "Mr. C___".

*Died:

Jose P. Laurel

José Paciano Laurel y García (; March 9, 1891 – November 6, 1959) was a Filipino people, Filipino politician, lawyer, and judge, who served as the president of the Japanese-occupied Second Philippine Republic, a puppet state during World W ...

, 68, President of the Philippines during Japanese occupation; Laurel was installed as the leader of the Japanese puppet-state, the

Second Philippine Republic

The Second Philippine Republic, officially known as the Republic of the Philippines ( tl, Repúbliká ng Pilipinas; es, República de Filipinas; ja, フィリピン共和国, ''Firipin-kyōwakoku'') and also known as the Japanese-sponsored Phi ...

, from 1943 to 1946 and later received amnesty for collaboration with the enemy

November 7, 1959 (Saturday)

*The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the

Taft-Hartley Act, and ordered 500,000 striking steelworkers to return to work for the next 80 days. In an 8–1 decision, Justice Douglas dissenting, the Court declared that the strike "imperils the national safety".

*After his troops had control of most of the disputed

Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu ...

border region with India, China's Premier

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Ma ...

proposed that both sides withdraw their troops. When the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

was fought in 1962, China insisted on the border being based on the

lines of "actual control" of 1959.

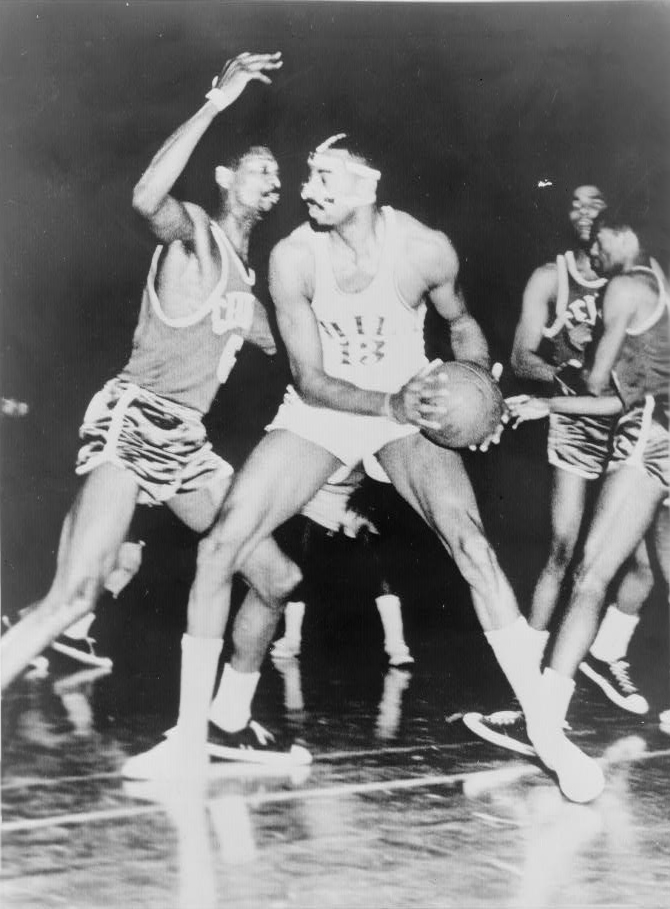

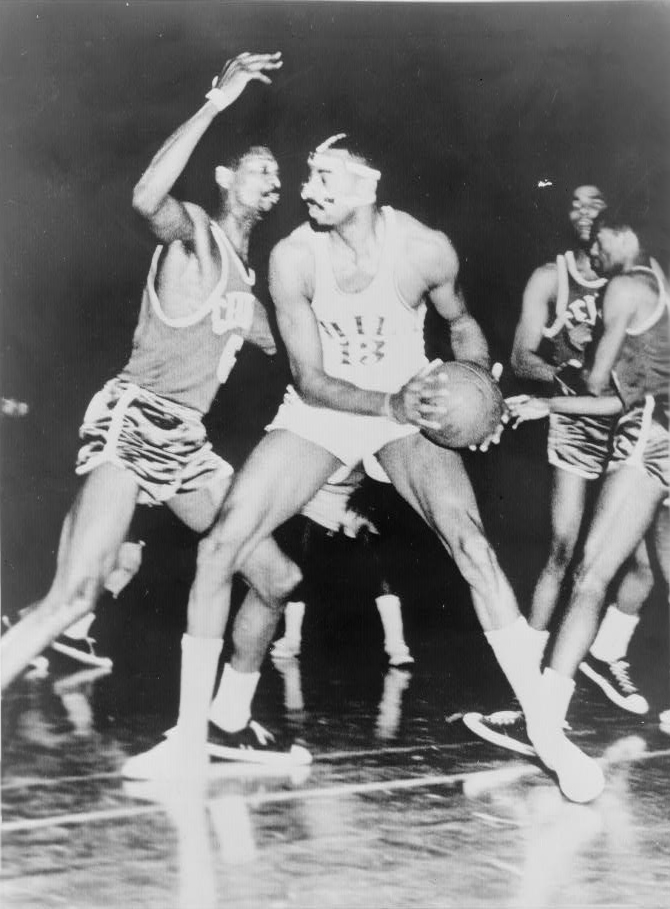

*The

rivalry

A rivalry is the state of two people or groups engaging in a lasting competitive relationship. Rivalry is the "against each other" spirit between two competing sides. The relationship itself may also be called "a rivalry", and each participant ...

between

Bill Russell

William Felton Russell (February 12, 1934 – July 31, 2022) was an American professional basketball player who played as a center for the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1956 to 1969. A five-time NBA Most Va ...

and

Wilt Chamberlain

Wilton Norman Chamberlain (; August 21, 1936 – October 12, 1999) was an American professional basketball player who played as a center. Standing at tall, he played in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for 14 years and is widely reg ...

began as Russell and the

Boston Celtics defeated Chamberlain's

Philadelphia Warriors, 115–106. During the 1960s, Chamberlain won more scoring titles, while Russell won more team championships. Their last meeting was in Game 7 of the

1969 NBA Finals

The 1969 NBA World Championship Series to determine the champion of the 1968–69 NBA season was played between the Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics, the Lakers being heavily favored due to the presence of three formidable stars: Elgin Bayl ...

(May 5), when Boston beat the

Los Angeles Lakers 108–106.

*Born:

Billy Gillispie

Billy Clyde Gillispie ( ; born November 7, 1959), also known by his initials BCG and Billy Clyde, is an American college basketball and current men's basketball coach at Tarleton State. Gillispie had previously been head coach at UTEP, Texas A ...

, American basketball coach, in

Abilene, Texas

*Died:

Victor McLaglen

Victor Andrew de Bier Everleigh McLaglen (10 December 1886 – 7 November 1959) was a British boxer-turned-Hollywood actor.Obituary ''Variety'', 11 November 1959, page 79. He was known as a character actor, particularly in Westerns, and made sev ...

, 72, Western actor

November 8, 1959 (Sunday)

*

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and the

Sudan signed a treaty governing use of the

Nile River, clearing the way for construction projects there.

*

Habib Bourguiba, the

President of Tunisia

The president of Tunisia, officially the president of the Tunisian Republic ( ar, رئيس الجمهورية التونسية), is the head of state of Tunisia. Tunisia is a presidential republic, whereby the president is the head of state a ...

, was unopposed in his first election bid, as were all 90 candidates for the legislative seats in the

Majlis al-Nuwaab.

*Between this date and December 5, 1959, the tentative design and layout of the

Mercury Control Center __NOTOC__

The Mercury Control Center (also known as Building 1385 or simply MCC) provided control and coordination of all activities associated with the NASA's Project Mercury flight operation as well as the first three Project Gemini flights (the ...

to be used to monitor the orbiting flight of the

Mercury spacecraft

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

were completed. The control center would have trend charts to indicate the

astronaut's condition and world map displays to keep continuous track of the Mercury spacecraft.

*

Elgin Baylor

Elgin Gay Baylor ( ; September 16, 1934 – March 22, 2021) was an American professional basketball player, coach, and executive. He played 14 seasons as a forward in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the Minneapolis/Los Angeles Lak ...

broke the NBA scoring record with 64 points in the

Minneapolis Lakers

The Los Angeles Lakers franchise has a long and storied history, predating the formation of the National Basketball Association (NBA).

Founded in 1947, the Lakers are one of the NBA's most famous and successful franchises. As of summer 2012, th ...

' 136–115 win over the visiting

Boston Celtics.

*Born:

**

Selçuk Yula, Turkish footballer, in

Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

(d. 2013)

*Died:

**

Frank S. Land, 69, founder of the

Order of DeMolay

DeMolay International is an international fraternal organization for young men ages 12 to 21. It was founded in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1919 and named for Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. DeMolay was incorpora ...

**

William Langer

William "Wild Bill" Langer (September 30, 1886November 8, 1959) was a prominent American lawyer and politician from North Dakota, where he was an infamous character, bouncing back from a scandal that forced him out of the governor's office and ...

, 73,

U.S. Senator from

North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

since 1941

November 9, 1959 (Monday)

*Seventeen days before Thanksgiving,

Arthur Flemming

Arthur Sherwood Flemming (June 12, 1905September 7, 1996) was an American government official. He served as the United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare from 1958 until 1961 under President Dwight D. Eisenhower's administration ...

, the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, warned that some of the 1959 crop of

cranberries

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus ''Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species ''Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranberry ...

was tainted with the carcinogen

aminotriazole, and said that if a housewife did not know where the berries in a product came from, "to be on the safe side, she doesn't buy". Cranberry sales plummeted, but producers responded by finding ways to promote year-round sales of cranberry products, including

cranberry juice

Cranberry juice is the liquid juice of the cranberry, typically manufactured to contain sugar, water, and other fruit juices. Cranberry – a fruit native to North America – is recognized for its bright red color, tart taste, and versat ...

.

*The first

Ski-doo

Ski-Doo is a brand name of snowmobile manufactured by Bombardier Recreational Products (originally Bombardier Inc. before the spin-off). The Ski-Doo personal snowmobile brand is so iconic, especially in Canada, that it was listed in 17th place ...

, a

snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known as a Ski-Doo, snowmachine, sled, motor sled, motor sledge, skimobile, or snow scooter, is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow. It is designed to be operated on snow and ice and does not ...

with a new, light-weight (30 pound) engine, was manufactured in

Valcourt,

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, one of 250 made on the first day of production. The lighter engine made snowmobiling more practical, and within a decade, more than 200,000 Ski-doos were being sold annually in North America.

*Born:

**

Tony Slattery

Tony Declan James Slattery (born 9 November 1959) is an English actor and comedian. He appeared on British television regularly from the mid-1980s, most notably as a regular on the Channel 4 improvisation show '' Whose Line Is It Anyway?'' His ...

, British comedian and TV actor, in

Stonebridge, London

**

Donnie McClurkin

Donald Andrew "Donnie" McClurkin, Jr. (born November 9, 1959) is an American gospel singer and minister. He has won three Grammy Awards, ten Stellar Awards, two BET Awards, two Soul Train Awards, one Dove Award and one NAACP Image Awards. ...

, American gospel singer, in

Amityville, New York

Amityville () is a village near the Town of Babylon in Suffolk County, on the South Shore of Long Island, in New York. The population was 9,523 at the 2010 census.

History

Huntington settlers first visited the Amityville area in 1653 du ...

**

Angela Spivey, American gospel singer, in

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

November 10, 1959 (Tuesday)

*, at in length and 5,000 tons the largest

submarine to that time, joined the U.S. Navy's nuclear sub force. With two nuclear reactors, the ''Triton'' had cost $100,000,000 to build. Meanwhile, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev claimed in an interview that he had told President Eisenhower in August that "your submarines are not so bad, but the speed of our atomic submarines is double yours."

*

Space Task Group

The Space Task Group was a working group of NASA engineers created in 1958, tasked with managing America's human spaceflight programs. Headed by Robert Gilruth and based at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, it managed Project Me ...

personnel visited

McDonnell

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer based in St. Louis, Missouri. The company was founded on July 6, 1939, by James Smith McDonnell, and was best known for its military fighters, including the F-4 Phantom I ...

to monitor the molding of the first production-type couch for the Mercury spacecraft.

*Born:

**

Linda Cohn

Linda Cohn (born ) is an American sportscaster. She anchors ESPN's ''SportsCenter''.

Early life and education

Cohn grew up in a Jewish family on Long Island, New York. As a child, she would watch sports on TV with her father, who is a huge sp ...

, the first full-time female sports anchor in the United States; in

Selden, New York

Selden is a hamlet (and census-designated place) in the Town of Brookhaven in Suffolk County, New York, United States. The population was 19,851 at the 2010 census.

History Early settlement

The farmers who first moved to what is now Selden in the ...

**

Mackenzie Phillips, American TV actress (''One Day at a Time''); in

Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city in the northern region of the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of downtown Washington, D.C.

In 2020, the population was 159,467. ...

November 11, 1959 (Wednesday)

*

Werner Heyde

Werner Heyde (aka Fritz Sawade) (25 April 1902 – 13 February 1964) was a German psychiatrist. He was one of the main organizers of Nazi Germany's T-4 Euthanasia Program.

Early life

Heyde was born in Forst (Lausitz), on May 25, in 1902, and com ...

, a psychiatrist who had guided the euthanizing of more than 100,000 handicapped persons in

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, surrendered to police in

Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

after 13 years as a fugitive. As director of the Reich Association of Hospitals, Dr. Heyde had carried out "

Action T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of t ...

". Men, women and children who were mentally or physically handicapped were the victims of Heyde's "mercy killing" from 1939 to 1942, usually by lethal injection. Sentenced ''in absentia'' to death, Heyde had been practicing in

Flensburg as "Dr. Fritz Sawade". On February 13, 1964, five days before his trial was to start, Dr. Heyde hanged himself at the prison in

Butzbach

Butzbach () is a town in the Wetteraukreis district in Hessen, Germany. It is located approximately 16 km south of Gießen and 35 km north of Frankfurt am Main.

In 2007, the town hosted the 47th Hessentag state festival from 1 to 10 June ...

.

November 12, 1959 (Thursday)

*

William Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil

William Shepherd Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil, (10 August 1893 – 3 February 1961), was a British politician. He was a long-serving cabinet minister before serving as Speaker of the House of Commons from 1951 to 1959. He was then appoint ...

was selected to become the new

Governor-General of Australia. Morrison, a native of Scotland, had retired earlier in the year as

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

. Prior to his selection, it was speculated that

Princess Margaret, sister to

Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, would be selected as the Head of State and representative of the Crown in Australia.

*

NASA Administrator

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is the highest-ranking official of NASA, the national space agency of the United States. The administrator is NASA's chief decision maker, responsible for providing clarity to ...

T. Keith Glennan

Thomas Keith Glennan (September 8, 1905 – April 11, 1995) was the first Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, serving from August 19, 1958 to January 20, 1961.

Early career

Born in Enderlin, North Dakota, the so ...

and

Deputy Secretary of Defense

The deputy secretary of defense (acronym: DepSecDef) is a statutory office () and the second-highest-ranking official in the Department of Defense of the United States of America.

The deputy secretary is the principal civilian deputy to the sec ...

Thomas S. Gates Jr.

Thomas Sovereign Gates Jr. (April 10, 1906March 25, 1983) was an American politician and diplomat who served as Secretary of Defense from 1959 to 1961 and Secretary of the Navy from 1957 to 1959, both under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. During ...

signed a

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

-

Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

agreement, relevant to the principles governing reimbursement of costs incurred by NASA or the Department of Defense in support of

Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

.

November 13, 1959 (Friday)

*The

Narrows Bridge in

Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

, Australia, was opened to traffic. At the time, the structure was the largest in the world to be made of

precast

Precast concrete is a construction product produced by casting concrete in a reusable mold or "form" which is then cured in a controlled environment, transported to the construction site and maneuvered into place; examples include precast bea ...

and

prestressed concrete

Prestressed concrete is a form of concrete used in construction. It is substantially "prestressed" ( compressed) during production, in a manner that strengthens it against tensile forces which will exist when in service. Post-tensioned concreted i ...

.

November 14, 1959 (Saturday)

*

Kilauea on the island of

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

had begun to swell in September. At , the volcano erupted, producing fires of lava up to high. The fire fountains ceased by December 20.

*Born:

Paul McGann

Paul John McGann (; born 14 November 1959) is an English actor. He came to prominence for portraying Percy Toplis in the television serial '' The Monocled Mutineer'' (1986), then starred in the dark comedy '' Withnail and I'' (1987), which wa ...

, British TV actor, in

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

November 15, 1959 (Sunday)

*Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, and their teenage children, Nancy and Kenyon, were murdered at their home near

Holcomb, Kansas

Holcomb is a city in Finney County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 2,245.

History

Holcomb took its name from a local hog farmer. The city was a station and shipping point on the Atchison, Topeka ...

. Dick Hickock and Perry Smith would be captured in January, and hanged in 1965. The killings were immortalized in

Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

's 1966 book, ''

In Cold Blood''.

*Born:

Robert Draper

Robert Draper (born November 15, 1959) is an American journalist, and author of '' Do Not Ask What Good We Do: Inside the U.S. House of Representatives''. He is a correspondent for '' GQ'' and a contributor to ''The New York Times Magazine''. Pre ...

, American journalist and author, in

Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 i ...

*Died:

C. T. R. Wilson, 90, Scottish physicist, inventor of the

cloud chamber

A cloud chamber, also known as a Wilson cloud chamber, is a particle detector used for visualizing the passage of ionizing radiation.

A cloud chamber consists of a sealed environment containing a supersaturated vapour of water or alcohol. An ...

, for which he won the

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1927

November 16, 1959 (Monday)

*''

The Sound of Music

''The Sound of Music'' is a musical with music by Richard Rodgers, lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, and a book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. It is based on the 1949 memoir of Maria von Trapp, ''The Story of the Trapp Family Singers''. S ...

'', written by

Rodgers and Hammerstein

Rodgers and Hammerstein was a theater-writing team of composer Richard Rodgers (1902–1979) and lyricist-dramatist Oscar Hammerstein II (1895–1960), who together created a series of innovative and influential American musicals. Their popular ...

's music and lyrics, premiered on

Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

at the

Lunt-Fontanne Theatre

The Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, originally the Globe Theatre, is a Broadway theater at 205 West 46th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1910, the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre was designed by Carrère and Hasti ...

.

Mary Martin

Mary Virginia Martin (December 1, 1913 – November 3, 1990) was an American actress and singer. A muse of Rodgers and Hammerstein, she originated many leading roles on stage over her career, including Nellie Forbush in '' South Pacific'' (194 ...

starred as

Maria von Trapp

Baroness Maria Augusta von Trapp DHS (; 26 January 1905 – 28 March 1987) was the stepmother and matriarch of the Trapp Family Singers. She wrote ''The Story of the Trapp Family Singers'', which was published in 1949 and was the inspiratio ...

.

*

National Airlines Flight 967

National Airlines Flight 967, registration was a Douglas DC-7B aircraft that disappeared over the Gulf of Mexico en route from Tampa, Florida, to New Orleans, Louisiana, on November 16, 1959. All 42 on board were presumed killed in the incident ...

, with 42 people on board, crashed into the Gulf of Mexico while en route from

Tampa to

. Though an onboard bomb was suspected, the physical evidence was lost in the Gulf.

*From November 16 to 20, wearing the

Mercury pressure suits, the astronauts were familiarized with the expected reentry heat pulse at the

Navy Aircrew Equipment Laboratory,

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

,

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

.

November 17, 1959 (Tuesday)

*The London ''

Daily Herald'' revealed a plot to kidnap

Prince Charles, the 11-year-old heir to the British throne, from his boarding school, but most observers scoffed at the exclusive story. Beneath the banner headline "ROYAL KIDNAP QUIZ" came the story that the

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

nationalist group

Fianna Uladh planned to raid the

Cheam School to take Charles hostage. A spokesman for Scotland Yard opined that the story had been made up by the ''Herald'' "because we refused to give information about why security measures were increased at Cheam School". The newspaper ceased publication in 1964.

*Born:

William R. Moses, American TV actor; in

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

*Died:

Heitor Villa-Lobos, 72, Brazilian composer

November 18, 1959 (Wednesday)

*''

Ben-Hur'', which would go on to become the most popular film of the year and would win a record 12 Academy Awards, debuted at New York's Loews Theater in

Ultra Panavision

Ultra Panavision 70 and MGM Camera 65 were, from 1957 to 1966, the marketing brands that identified motion pictures photographed with Panavision's anamorphic movie camera lenses on 65 mm film. Ultra Panavision 70 and MGM Camera 65 were shot at 24 f ...

, before nationwide and then worldwide release.

*

Ornette Coleman became a sensation in the world of

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

with his East Coast debut at the "Five Spot Cafe" in New York's

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. Described by one critic as "the only really new thing in jazz since ... the mid 40s", the alto saxophonist's style received a mixed reaction.

*Born:

Jimmy Quinn, footballer and manager, in

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

November 19, 1959 (Thursday)

*''

The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show

''The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends'' (commonly referred to as simply ''Rocky and Bullwinkle'') is an American animated television series that originally aired from November 19, 1959, to June 27, 1964, on the ABC and NBC te ...

'' was introduced. The cartoon was shown on ABC network stations at 5:30 each afternoon and was originally called ''Rocky and Friends'', although Bullwinkle the moose soon became more popular than Rocky the flying squirrel.

*In its third unsuccessful year, the last

Edsel

Edsel is a discontinued division and brand of automobiles that was marketed by the Ford Motor Company from the 1958 to the 1960 model years. Deriving its name from Edsel Ford, son of company founder Henry Ford, Edsels were developed in an effor ...

automobile was manufactured by the

Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobi ...

, after a loss of $100,000,000 on the program. Eighteen of the 1960 Edsels were produced on the final day.

*Born:

Allison Janney

Allison Brooks Janney (born November 19, 1959) is an American actress. In a career spanning three decades, she is known for her performances across multiple genres of screen and stage. Janney has received various accolades, including an Academ ...

, American actress (''The West Wing''), in

Dayton

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Da ...

*Died:

**

Edward C. Tolman

Edward Chace Tolman (April 14, 1886 – November 19, 1959) was an American psychologist and a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Through Tolman's theories and works, he founded what is now a branch of psychology know ...

, 73, American psychologist

**

Aleksandr Khinchin

Aleksandr Yakovlevich Khinchin (russian: Алекса́ндр Я́ковлевич Хи́нчин, french: Alexandre Khintchine; July 19, 1894 – November 18, 1959) was a Soviet mathematician and one of the most significant contributors to th ...

, 65, Soviet mathematician

November 20, 1959 (Friday)

*The

Declaration of the Rights of the Child

The Declaration of the Rights of the Child, sometimes known as the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, is an international document promoting child rights, drafted by Eglantyne Jebb and adopted by the League of Nations in 1924, and adop ...

, a set of ten principles introduced by the resolution, "Whereas, mankind owes to the child the best it has to give", was passed unanimously by the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, as Resolution 1386 of the 14th Session.

*The

Army Ballistic Missile Agency

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) was formed to develop the U.S. Army's first large ballistic missile. The agency was established at Redstone Arsenal on 1 February 1956, and commanded by Major General John B. Medaris with Wernher von ...

proposed the installation of an open-circuit television system in the

Mercury-Redstone 2

Mercury-Redstone 2 (MR-2) was the test flight of the Mercury-Redstone Launch Vehicle just prior to the first crewed American space mission in Project Mercury. Carrying a chimpanzee named Ham on a suborbital flight, Mercury spacecraft Number 5 w ...

and

Mercury-Redstone 3

Mercury-Redstone 3, or ''Freedom 7'', was the first United States human spaceflight, on May 5, 1961, piloted by astronaut Alan Shepard. It was the first crewed flight of Project Mercury. The project had the ultimate objective of putting an as ...

flights.

*Died:

Roy Thomas, 85, American baseball player

November 21, 1959 (Saturday)

*The career of nationally known disc jockey

Alan Freed

Albert James "Alan" Freed (December 15, 1921 – January 20, 1965) was an American disc jockey. He also produced and promoted large traveling concerts with various acts, helping to spread the importance of rock and roll music throughout Nor ...

ended with his firing from New York's most popular rock station,

WABC (AM)

WABC (770 AM) is a commercial radio station licensed to New York, New York, carrying a conservative talk format known as "Talkradio 77". Owned by John Catsimatidis' Red Apple Media, the station's studios are located in Red Apple Media headqu ...

, after he refused to sign an affidavit denying involvement in the

"payola" scandal. As a DJ for WABC, Freed had promoted selected singles for undisclosed financial gain.

Dick Clark

Richard Wagstaff Clark (November 30, 1929April 18, 2012) was an American radio and television personality, television producer and film actor, as well as a cultural icon who remains best known for hosting '' American Bandstand'' from 1956 to 19 ...

, host of TV's ''

American Bandstand'', signed a similar affidavit and had divested himself of financial interests, and his career was not interrupted by the scandal.

*The first inter-league trade without waivers in major league baseball history took place when the

Chicago Cubs sent

Jim Marshall and

Dave Hillman to the

Boston Red Sox

The Boston Red Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Boston. The Red Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) East division. Founded in as one of the American League's eigh ...

in return for

Dick Gernert.

*The

Phoenix Art Museum

The Phoenix Art Museum is the largest museum for visual art in the southwest United States. Located in Phoenix, Arizona, the museum is . It displays international exhibitions alongside its comprehensive collection of more than 18,000 works of ...

was opened in Arizona.

*Died:

Max Baer, 50, American boxer who was

world heavyweight champion

At boxing's beginning, the heavyweight division had no weight limit, and historically the weight class has gone with vague or no definition. During the 19th century many heavyweights were 170 pounds (12 st 2 lb, 77 kg) or less, tho ...

in 1934 and 1935.

November 22, 1959 (Sunday)

*The stop-motion children's program ''

Unser Sandmännchen'' ("Our

Sandman

The Sandman is a mythical character in European folklore who puts people to sleep and encourages and inspires beautiful dreams by sprinkling magical sand onto their eyes.

Representation in traditional folklore

The Sandman is a traditional charact ...

") premiered on

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

's state television network

Deutscher Fernsehfunk

Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF; German for "German Television Broadcasting") was the state television broadcaster in the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany) from 1952 to 1991.

DFF produced free-to-air terrestrial television programmin ...

(DFF) as a 10-minute long show bedtime story. In

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, a different version called ''Sandmännchen'' premiered nine days later at the same time on the

ARD network of stations. The West German version would stop being shown after March 31, 1989, while the East German series would continue to be shown after the reunification of Germany and continued to be seen more than 60 years later.

*In

Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

, on the morning of the

American Football League's first owners' meeting, the Minneapolis ''Star-Journal'' carried the headline "MINNESOTA TO GET NFL FRANCHISE". The owners of the AFL Minneapolis team denied the story, but soon were awarded the NFL's 14th team, the

Minnesota Vikings

The Minnesota Vikings are a professional American football team based in Minneapolis. They compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the National Football Conference (NFC) North division. Founded in 1960 as an expansi ...

. Legend has it that

Harry Wismer

Harry Wismer (June 30, 1913 – December 4, 1967) was an American sports broadcaster and the charter owner of the New York Titans franchise in the American Football League (AFL).

Early years

Harry Wismer was born on June 30, 1911 in Port Huron ...

brought copies of the newspaper to a banquet, pointed to

Max Winter

Max Winter (June 29, 1903 – July 26, 1996) was a Minneapolis businessman and sport executive who helped found the Minnesota Vikings.

Biography

Winter was born in Ostrava, Austria-Hungary (modern day Czechia). He emigrated with his family an ...

, and said, "This is the last supper. And he's Judas!" The Minneapolis AFL team was replaced by the

Oakland Raiders.

* The

New England Patriots American football team, known then as the Boston Patriots, was founded by

Billy Sullivan in Boston, United States.

*Died:

Sam M. Lewis, 74, American songwriter

November 23, 1959 (Monday)

*The

Curtiss-Wright

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is a manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation of Curtiss, Wright, and v ...

Corporation announced that it had developed a new internal combustion engine, in conjunction with

NSU Motorenwerke AG

NSU Motorenwerke AG, or NSU, was a German manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles and pedal cycles, founded in 1873. Acquired by Volkswagen Group in 1969, VW merged NSU with Auto Union, creating Audi NSU Auto Union AG, ultimately Audi. The nam ...

of Germany. With only two moving parts (the rotor and the crankshaft) this would later be called the

rotary engine

The rotary engine is an early type of internal combustion engine, usually designed with an odd number of cylinders per row in a radial configuration. The engine's crankshaft remained stationary in operation, while the entire crankcase and its ...

.

*African track athletes

Yotham Muleya

Yotam Siachobe Muleya (1940 – 23 November 1959) was a long-distance runner who represented Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Muleya broke racial barriers and opened a new era in Rhodesian sport when he ...

and John Winter, both students at

Central Michigan College, were fatally injured in a car crash near

Mt. Pleasant, Michigan, while on their way to a track meet at

Michigan State University in

East Lansing

East Lansing is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan. Most of the city lies within Ingham County with a smaller portion extending north into Clinton County. At the 2020 Census the population was 47,741. Located directly east of the state capital ...

. The car in which they were riding went out of control after passing another vehicle and collided head-on with the car of two men on a hunting trip, killing both hunters. Muleya, the three-mile champion of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and the first black African to be permitted to run in a track meet in the segregated Southern Rhodesia, died later in the day, while his friend Winter of Southern Rhodesia, a white athlete who held the Rhodesian record for the quarter mile, died five days later.

*Born:

Dominique Dunne

Dominique Ellen Dunne (November 23, 1959 – November 4, 1982) was an American actress. Born and raised in Santa Monica, California, Dunne studied acting at Milton Katselas' Workshop, where she appeared in stage productions. She made her ...

, American actress (''Poltergeist''), in

Santa Monica

Santa Monica (; Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 U.S. Census population was 93,076. Santa Monica is a popular resort town, owing to i ...

; she was killed in 1982 by her boyfriend shortly after the release of the film

November 24, 1959 (Tuesday)

*TWA Flight 595, a cargo plane with three crew members on board, crashed into a

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

neighborhood adjacent to

Midway Airport. At , the Constellation airplane crashed at the corner of 64th Street and Knox Avenue, and destroyed apartments and bungalows. In addition to the crew, eight people on the ground were killed and 13 more injured.

*Near

Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

, the

Proton Synchrotron

The Proton Synchrotron (PS, sometimes also referred to as CPS) is a particle accelerator at CERN. It is CERN's first synchrotron, beginning its operation in 1959. For a brief period the PS was the world's highest energy particle accelerator. It ...

developed by the European nuclear agency,

CERN, went online and exceeded expectations, accelerating protons to 25

GeV GEV may refer to:

* ''G.E.V.'' (board game), a tabletop game by Steve Jackson Games

* Ashe County Airport, in North Carolina, United States

* Gällivare Lapland Airport, in Sweden

* Generalized extreme value distribution

* Gev Sella, Israeli-Sou ...

(

electron volts), more than twice as much as the Soviet synchrotron at

Dubna

Dubna ( rus, Дубна́, p=dʊbˈna) is a town in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It has a status of ''naukograd'' (i.e. town of science), being home to the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, an international nuclear physics research center and one o ...

.

*Died:

Herbert "Daily" Messenger, 76, Australian rugby league star

November 25, 1959 (Wednesday)

*The first

Bilateral Investment Treaty

A bilateral investment treaty (BIT) is an agreement establishing the terms and conditions for private investment by nationals and companies of one state in another state. This type of investment is called foreign direct investment (FDI). BITs ar ...

(BIT) in history was signed between

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

and Pakistan. BITs govern the terms of private investment between companies in the two nations, including provisions for arbitration of disputes.

*Born:

Charles Kennedy

Charles Peter Kennedy (25 November 1959 – 1 June 2015) was a British Liberal Democrat politician who served as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 1999 to 2006, and was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Ross, Skye and Lochaber from 1983 ...

, Scottish member of the British House of Commons and

Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 1999 to 2006; in

Inverness (d. 2015)

November 26, 1959 (Thursday)

*The maiden flight of the

Atlas-Able

The Atlas-Able was an American expendable launch system derived from the SM-65 Atlas missile. It was a member of the Atlas family of rockets, and was used to launch several Pioneer spacecraft towards the Moon. Of the five Atlas-Able rockets built ...

rocket, the most powerful ever built by the United States, failed less than a minute after its launch. The rocket lifted off at from

Cape Canaveral, with plans to carry the Pioneer V satellite to be placed in lunar orbit. Forty seconds later, parts fell from the third stage and the rocket misfired.

*Born:

Dai Davies, Welsh politician and independent

MP, in

Ebbw Vale

November 27, 1959 (Friday)

*More than 20,000 protesters in Tokyo, demanding that Japan end its military ties with the United States, stormed the grounds of the

Japanese parliament

The is the national legislature of Japan. It is composed of a lower house, called the House of Representatives (, ''Shūgiin''), and an upper house, the House of Councillors (, '' Sangiin''). Both houses are directly elected under a paralle ...

. In the ensuing riot, 159 policemen and 212 civilians were injured in the worst violence in Japan since the May Day riots of 1952.

*Nazi war criminal Dr.

Josef Mengele

, allegiance =

, branch = Schutzstaffel

, serviceyears = 1938–1945

, rank = '' SS''-'' Hauptsturmführer'' (Captain)

, servicenumber =

, battles =

, unit =

, awards =

, commands =

, ...

, the "Angel of Death" at the

Auschwitz and

Birkenau concentration camps, was granted citizenship by

Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, whose dictator

Alfredo Stroessner

Alfredo Stroessner Matiauda (; 3 November 1912 – 16 August 2006) was a Paraguayan army officer and politician who served as President of Paraguay from 15 August 1954 to 3 February 1989.

Stroessner led a coup d'état on 4 May 1954 with t ...

refused to allow the extradition of a Paraguayan citizen. Mengele later fled to Brazil, and was never captured, living until 1979 when he drowned.

*Born:

Viktoria Mullova

Viktoria Yurievna Mullova ( rus, Виктория Юрьевна Муллова, , vʲɪˈktorʲɪɪ̯ə ˈmuɫəvə; born 27 November 1959) is a Russian-born British violinist. She is best known for her performances and recordings of a number ...

, Russian violinist, in

Zhukovsky

November 28, 1959 (Saturday)

*Victims of the mercury-poisoning induced

Minamata disease

Minamata disease is a neurological disease caused by severe mercury poisoning. Signs and symptoms include ataxia, numbness in the hands and feet, general muscle weakness, loss of peripheral vision, and damage to hearing and speech. In extrem ...

, and their families, began a

sit-in at the chemical factory operated by

Chisso

The , since 2012 reorganized as JNC (Japan New Chisso), is a Japanese chemical company. It is an important supplier of liquid crystal used for LCDs, but is best known for its role in the 34-year-long pollution of the water supply in Minamata, ...

in

Minamata, Japan, and after a month's protest, secured an

agreement Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting o ...

for injury compensation.

*The first of the

Nashville sit-ins

The Nashville sit-ins, which lasted from February 13 to May 10, 1960, were part of a protest to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. The sit-in campaign, coordinated by the Nashville Student Movement and th ...

, aimed at ending the policy of discrimination against African-Americans at lunch counters, began with a test run at

Harveys Department Store in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. By 1960, the nonviolent protests were being duplicated, successfully and nationwide.

*

Saint Louis University won the first ever

NCAA college soccer tournament, beating the

University of Bridgeport

The University of Bridgeport (UB) is a private university in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The university is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education. In 2021, the university was purchased by Goodwin University; it retain its own ...

, 5 to 2, in the championship game of the 8-team playoff.

*Born:

Judd Nelson

Judd Asher Nelson (born November 28, 1959) is an American actor. He is best known for his roles as John Bender in ''The Breakfast Club'', Alec Newbury in ''St. Elmo's Fire'', Joe Hunt in '' Billionaire Boys Club'', Nick Peretti in ''New Jack Cit ...

, American actor (''

The Breakfast Club

''The Breakfast Club'' is a 1985 American teen coming-of-age comedy-drama film written, produced, and directed by John Hughes. It stars Emilio Estevez, Paul Gleason, Anthony Michael Hall, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, and Ally Sheedy. The ...

''), in

Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

November 29, 1959 (Sunday)

*The Reverend

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, preached his final sermon as pastor of the

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

, resigning to devote more time to the civil rights movement.

*Born:

Rahm Emanuel

Rahm Israel Emanuel (; born November 29, 1959) is an American politician and diplomat who is the current United States Ambassador to Japan. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served two terms as the 55th Mayor of Chicago from 2011 ...

,

Mayor of Chicago (2011-2019) and

White House Chief of Staff (2009-2010); in

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

November 30, 1959 (Monday)

*In Hungary,

János Kádár

János József Kádár (; ; 26 May 1912 – 6 July 1989), born János József Czermanik, was a Hungarian communist leader and the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, a position he held for 32 years. Declining health l ...

, leader of that nation's

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

since the Soviet invasion of 1956, announced that the nearly 60,000 Soviet troops stationed in Hungary would remain "as long as the international situation demands it". Occupation forces remained until 1991.

*Born:

Lorraine Kelly

Lorraine Kelly, (born 30 November 1959) is a Scottish journalist and television presenter. She has presented various television shows for ITV, including '' Good Morning Britain'' (1988–1992), '' GMTV'' (1993–2010), ''This Morning'' (2003 ...

, Scottish

ITV news presenter; in

East Kilbride

East Kilbride (; gd, Cille Bhrìghde an Ear ) is the largest town in South Lanarkshire in Scotland and the country's sixth-largest locality by population. It was also designated Scotland's first new town on 6 May 1947. The area lies on a rais ...

November 1959

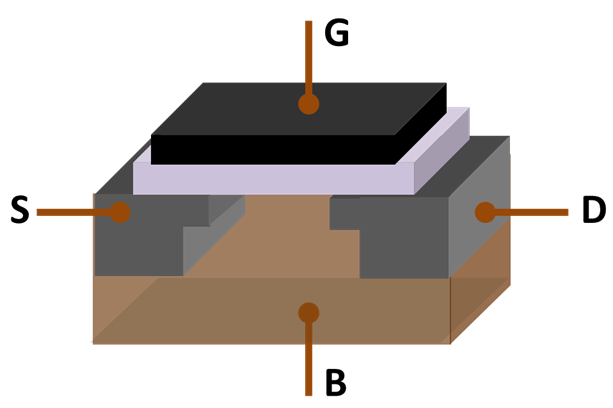

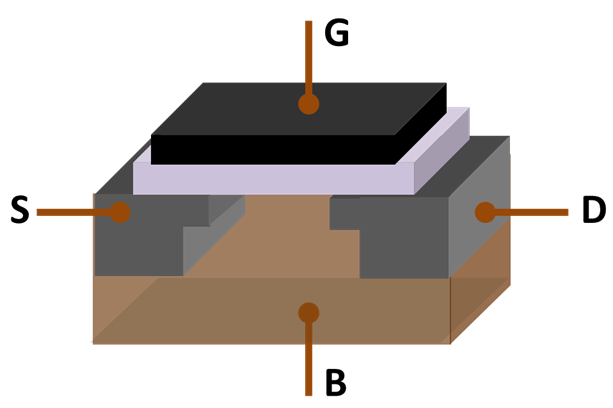

*The

MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor

field-effect transistor

The field-effect transistor (FET) is a type of transistor that uses an electric field to control the flow of current in a semiconductor. FETs ( JFETs or MOSFETs) are devices with three terminals: ''source'', ''gate'', and ''drain''. FETs cont ...

), also known as the MOS

transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch ...

, was invented by

Mohamed Atalla and

Dawon Kahng

Dawon Kahng ( ko, 강대원; May 4, 1931 – May 13, 1992) was a Korean-American electrical engineer and inventor, known for his work in solid-state electronics. He is best known for inventing the MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effe ...

at

Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial Research and development, research and scientific developm ...

in November 1959.

It revolutionized the

electronics industry,

and became the fundamental building block of the

Digital Revolution.

The MOSFET went on to become the most widely manufactured device in history.

References

{{Events by month links

1959

Events January

* January 1 - Cuba: Fulgencio Batista flees Havana when the forces of Fidel Castro advance.

* January 2 - Lunar probe Luna 1 was the first man-made object to attain escape velocity from Earth. It reached the vicinity of E ...

*1959-11

*1959-11

The following events occurred in November 1959:

The following events occurred in November 1959:

*

* *

* *Between this date and December 5, 1959, the tentative design and layout of the

*Between this date and December 5, 1959, the tentative design and layout of the

*Seventeen days before Thanksgiving,

*Seventeen days before Thanksgiving,  *In

*In  *The Reverend

*The Reverend  *The MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor

*The MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor