Novaya Zemlya on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an

, p. 58. Natural resources include

File:Barents' ship among the arctic ice.jpg, Willem Barentsz' ship among the Arctic ice.

File:India Orientalis - no-nb digibok 2013101026001-314.jpg, 1599–1601 map of Novaya Zemlya.

File:C.G. Zorgdragers Bloeyende opkomst der aloude en hedendaagsche Groenlandsche visschery - no-nb digibok 2014010724007-V6.jpg, Map of Novaya Zemlya from 1720.

Novaya Zemlya is an extension of the northern part of the

Novaya Zemlya is an extension of the northern part of the

File:Roze Glacier, Novaya Zemlya.jpg, Natural-color satellite image of the Nordenskiöld Glacier group. East coast, Severny

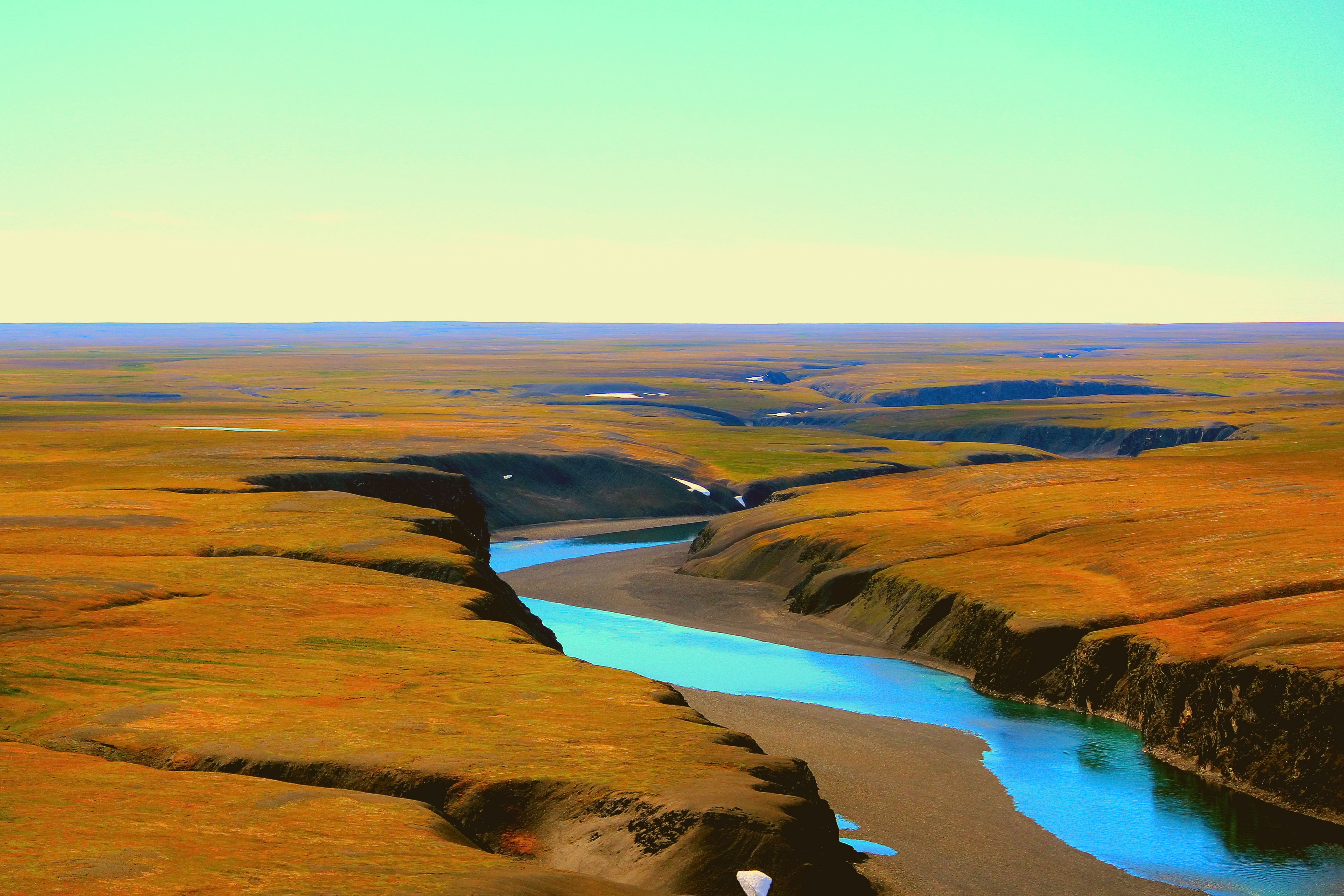

File:Novaya Zemlya - 27460478779.jpg, Wide shot of Novaya Zemlya

File:Barents-Bucht 1 2014-09-03.jpg, Barents Bay (Willem Barents' gravesite; )

File:Inostrantsewa-Gletscher 1 2014-09-05.jpg, Inostrantsev Glacier terminus ()

File:Kap Zhelanyia 2 2014-09-03.jpg, Cape Zhelaniya (Northernmost cape of Severny; )

Novaya Zemlya information portal

(global security).

* ttp://www.rozenbergps.com/index.php?frame=boek.php&item=295 Rozenberg Publishers – Climate and glacial history of the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago, Russian Arctic

Nuclear tests in Novaya Zemlya

International Atomic Energy Agency Department of Nuclear Safety and Security.

Испытание чистой водородной бомбы мощностью 50 млн тонн

declassified

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arch ...

in northern Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, in the extreme northeast of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, with Cape Flissingsky

Cape Flissingsky ( rus, Мыс Флиссингский; Mys Flissingskiy) is a cape on Northern Island, Novaya Zemlya, Russia. It is considered the easternmost point of Europe, including islands.

The cape was discovered by Willem Barents ...

, on the northern island, considered the easternmost point of Europe. To Novaya Zemlya's west lies the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian terr ...

and to the east is the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea (russian: Ка́рское мо́ре, ''Karskoye more'') is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipel ...

.

Novaya Zemlya consists of two main islands, the northern Severny Island and the southern Yuzhny Island, which are separated by the Matochkin Strait. Administratively, it is incorporated as Novaya Zemlya District, one of the twenty-one in Arkhangelsk Oblast

Arkhangelsk Oblast (russian: Арха́нгельская о́бласть, ''Arkhangelskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It includes the Arctic archipelagos of Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya, as well as the Solo ...

, Russia.Law #65-5-OZ Municipally, it is incorporated as Novaya Zemlya Urban Okrug.Law #258-vneoch.-OZ

The population of Novaya Zemlya as of the 2010 Census was about 2,429, of whom 1,972 resided in Belushya Guba

Belushya Guba (russian: Белу́шья Губа́, lit. ''beluga whale'' ''bay''), also Belushye (), is a work settlement and the administrative center of Novaya Zemlya District of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Gusinaya Zemlya pe ...

, an urban settlement that is the administrative center

An administrative center is a seat of regional administration or local government, or a county town, or the place where the central administration of a commune is located.

In countries with French as administrative language (such as Belgium, Lu ...

of Novaya Zemlya District.

The indigenous population (from 1872 to the 1950s when it was resettled to the mainland) consisted of about 50–300 Nenets who subsisted mainly on fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from fish stocking, stocked bodies of water such as fish pond, ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. ...

, trapping, reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subs ...

herding, polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a hypercarnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the largest extant bear spec ...

hunting and seal hunting.Ядерные испытания СССР. Том 1. Глава 2, p. 58. Natural resources include

copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

, and zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

.

Novaya Zemlya was a sensitive military area during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, and parts of it are still used for airfield

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publ ...

s today. The Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

maintained a presence at Rogachevo on the southern part of the southern island, on the westernmost peninsula (). It was used primarily for interceptor aircraft

An interceptor aircraft, or simply interceptor, is a type of fighter aircraft designed specifically for the defensive interception role against an attacking enemy aircraft, particularly bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Aircraft that are ...

operations, but also provided logistical support for the nearby nuclear test area. Novaya Zemlya was one of the two major nuclear test sites managed by the USSR; it was used for air drops and underground testing of the largest of Soviet nuclear bombs, in particular the October 30, 1961 air burst

An air burst or airburst is the detonation of an explosive device such as an anti-personnel artillery shell or a nuclear weapon in the air instead of on contact with the ground or target. The principal military advantage of an air burst over ...

explosion of Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, the largest, most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated.

History

The Russian people knew of Novaya Zemlya from the 11th century, when hunters fromNovgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

visited the area. For Western Europeans, the search for the Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: Се́верный морско́й путь, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of N ...

in the 16th century led to its exploration. The first visit from a Western European was by Hugh Willoughby in 1553. Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya in 1594, and in a subsequent expedition of 1596, he rounded the northern cape and wintered on the northeastern coast. (Barentsz died during the expedition, and may have been buried on Severny Island.) During a later voyage by Fyodor Litke in 1821–1824, the western coast was mapped. Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

was another explorer who passed through Novaya Zemlya while searching for the Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands o ...

.Henry Hudson in:

The islands were systematically surveyed by Pyotr Pakhtusov and Avgust Tsivolko during the early 1830s. The first permanent settlement was established in 1870 at Malye Karmakuly, which served as capital of Novaya Zemlya until 1924. Later, the administrative center was transferred to Belushya Guba

Belushya Guba (russian: Белу́шья Губа́, lit. ''beluga whale'' ''bay''), also Belushye (), is a work settlement and the administrative center of Novaya Zemlya District of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Gusinaya Zemlya pe ...

, in 1935 to Lagernoe, but then returned to Belushya Guba.

Small numbers of Nenets were resettled to Novaya Zemlya in the 1870s in a bid by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

to keep out the Norwegians

Norwegians ( no, nordmenn) are a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians a ...

. This population, then numbering 298, was transferred to the mainland in 1957 before nuclear testing began.

World War II

In the months following Hitler's June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, the United States and Great Britain organized convoys of merchant ships under naval escort to deliver Lend-Lease supplies to northern Soviet seaports. The Allied convoys up to PQ 12 arrived unscathed but German aircraft, ships and U-boats were sent to northern Norway and Finland to oppose the convoys.Convoy PQ 17

Convoy PQ 17

PQ 17 was the code name for an Allied Arctic convoy during the Second World War. On 27 June 1942, the ships sailed from Hvalfjörður, Iceland, for the port of Arkhangelsk in the Soviet Union. The convoy was located by German forces on 1 July, ...

consisted of thirty-six merchant ships containing 297 aircraft, 596 tanks, 4,286 other vehicles and more than of other cargo, six destroyer escorts, fifteen additional armed ships (among which were two Free-French corvettes) and three small rescue craft. The convoy departed Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

on June 27, 1942, one ship running aground and dropping out of the convoy. The convoy was able to sail north of Bear Island but encountered ice floes on June 30; a ship was damaged too badly to carry on and broke radio silence. On the following morning, the convoy was detected by German U-boats and German reconnaissance aircraft and torpedo bomber attacks began on July 2.

On the night of July 2/3, the German battleship '' Tirpitz'' and the heavy cruiser '' Admiral Hipper'', sortied from Trondheim with four destroyers and two smaller vessels. The pocket battleships ''Admiral Scheer

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer (30 September 1863 – 26 November 1928) was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commandi ...

'' and '' Lutzow'' and six destroyers sailed from Narvik, but ''Lutzow'' and three destroyers ran aground. The British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of i ...

responded on July 4 by diverting the escort vessels to the west to rendezvous with the Home Fleet and ordered the merchant vessels to scatter. Seeking safety in the Matochkin Strait, several ships headed toward Novaya Zemlya. S.A. Kerslake, a crew-member aboard the British trawler ''Northern Gem'', recorded in his diary:

When the ''Northern Gem'' approached Novaya Zemlya and neared the entrance to Matochkin Strait, it quickly reduced speed. Kerslake wrote:

Another seaman described the strait as "very barren and uninviting, but almost with 'Welcome' written along it."

On July 7 at 4:00 p.m., Captain J. H. Jauncey, the commander of the British anti-aircraft ship ''Palomares'', called a meeting of the commanders of the other ships which had reached the strait. At first, they discussed breaking into the Kara Sea from the east end of the Strait. An officer familiar with the region raised the possibility that the strait, navigable on the west end, might, at the other end, be ice-locked. A seaplane was dispatched which found that the eastern entrance was blocked. Other officers suggested that the ships remain in the strait until "the hue and cry had died down", adding that "the high cliffs on either side would afford some protection from dive-bombing".

The ships were painted white and positioned with its armament facing the west entrance. The French corvettes ''Lotus'' and ''La Malouine'' were dispatched to patrol the entrance to watch for German submarines.

At 7:00 p.m., the ships re-entered the Barents Sea and headed south. Anticipating the breakout, Rear Admiral Hubert Schmundt had positioned several U-boats near the west end of the strait. Six of the seventeen Allied ships exiting the strait were sunk. The badly-damaged American freighter ''Alcoa Ranger'' was beached on the west coast of Novaya Zemlya; the crew found shelter and were eventually rescued by a Russian vessel which took them to Belushya Bay. The Germans also damaged the Soviet tankers ''Donbass'' and ''Azerbaijan'' which reached the sanctuary of Archangel. Of the thirty-four merchant ships in PQ 17, twenty-four were sunk. The American contingent alone lost more than three-fourths of the merchant ships committed to the convoy — more than one fourth of the losses to American shipping in all convoys to northern Russia.

The PQ 17 delivered 896 vehicles and 3,350 were lost, 164 tanks arrived and 430 did not, 87 aircraft reached the USSR and 210 were lost; of cargo were delivered and was sunk at a cost to the Germans of five aircraft. Karlo Štajner, a Gulag prisoner in Norilsk in 1942, wrote "the German cruiser’s attack on Novaya Zemlya and the sinking of the food transports had catastrophic consequences… the population was left without provisions… supplies in the warehouses of Norilsk eredistributed among the NKVD, the guards, and the few free civilians that lived in the town". Štajner and his fellow prisoners received nothing. Between July and August 1942, German U-boats destroyed the ''Maliyye Karmakuly'' polar station and damaged the station at ''Mys Zhelaniya''. German warships also destroyed two Soviet seaplanes and staged an attack on ships in Belushya Bay.

Operation Wunderland

In August 1942, the German Navy commenced Operation Wunderland, to enter the Kara Sea and sink as many Soviet ships as possible. ''Admiral Scheer'' and other warships rounded Cape Desire, entered the Kara Sea and attacked a shore station onDikson Island

Dikson Island (russian: Ди́ксон), initially Dickson, is the name of an island in Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District (russian: Таймы́рский Долга́но-Не́нецкий райо́н), Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, situated ...

, badly damaging the Soviet ships ''Dezhnev'' and ''Revolutionist''. Later that year, Karlo Štajner made the acquaintance of a new prisoner, a Captain Menshikov, who told him that:

Whether the attack on Menshikov's battery occurred on Dikson Island or on Novaya Zemlya, Stajner's account illuminated the fate of a Soviet officer imprisoned by his countrymen for the "crime" of suffering defeat at the hands of the enemy. Not surprisingly, Menshikov's arrest was never announced in the Soviet press.

1943 operations

In August 1943, a German U-boat sank the Soviet research ship ''Akademic Shokalskiy'' near ''Mys Sporyy Navolok'' but the Soviet Navy, now on the offensive, destroyed the German submarine U-639 near ''Mys Zhelaniya''. In 1943, Novaya Zemlya briefly served as a secret seaplane base forNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'', to provide German surveillance of Allied shipping en route to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

. The seaplane base was established by U-255

German submarine ''U-255'' was a Type VIIC U-boat that served in Nazi Germany's '' Kriegsmarine'' during World War II. The submarine was laid down on 21 December 1940 at the Bremer Vulkan yard at Bremen-Vegesack, launched on 8 October 1941 ...

and U-711, which were operating along the northern coast of Soviet Russia as part of '' 13th U-boat Flotilla''. Seaplane sorties were flown in August and September 1943.

Nuclear testing

In July 1954, Novaya Zemlya was designated as the nuclear weapons testing venue, construction of which began in October and existed during much of theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. "Zone A", Chyornaya Guba Chyorny/Cherny (masculine), Chyornaya/Chernaya (feminine), or Chyornoye/Chernoye (neuter) may refer to:

*Daniil Chyorny (c. 1360–1430), Russian icon painter

*Vadim Chyorny (born 1997), Russian football player.

*Chyorny (inhabited locality) (' ...

(), was used in 1955–1962 and 1972–1975. "Zone B", Matochkin Shar (), was used for underground tests in 1964–1990. "Zone C", Sukhoy Nos (), was used in 1958–1961 and was the site of the 1961 test of the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated.

Other tests occurred elsewhere throughout the islands, with an official testing range covering over half of the landmass. In September 1961, two propelled thermonuclear warheads were launched from Vorkuta Sovetsky

Vorkuta Sovetskiy (also known as Vorkuta East) is a military airfield in the Komi Republic, Russia, located 11 km east of Vorkuta. It was one of nine Air Army staging bases in the Arctic for Russian bomber units.

and Salekhard to target areas on Novaya Zemlya. The launch rocket was subsequently deployed to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

.

1963 saw the implementation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty which banned most atmospheric nuclear tests. The largest underground test in Novaya Zemlya took place on September 12, 1973, involving four nuclear devices of 4.2 megatons total yield. Although far smaller in blast power than the Tsar Bomba and other atmospheric tests, the confinement of the blasts underground led to pressures rivaling natural earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s. In the case of the September 12, 1973 test, a seismic magnitude of 6.97 on the Richter Scale

The Richter scale —also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale—is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Francis Richter and presented in his landmark 1935 ...

was reached, setting off an 80 million ton avalanche

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope, such as a hill or mountain.

Avalanches can be set off spontaneously, by such factors as increased precipitation or snowpack weakening, or by external means such as humans, animals, and ea ...

that blocked two glacial streams and created a lake in length.

Over its history as a nuclear test site, Novaya Zemlya hosted 224 nuclear detonations with a total explosive energy equivalent to 265 megatons of TNT. For comparison, all explosives used in World War II, including the detonations of two US nuclear bombs, amounted to only two megatons.

In 1988–1989, ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' helped make the Novaya Zemlya testing activities public knowledge, and in 1990 Greenpeace

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, founded in Canada in 1971 by Irving Stowe and Dorothy Stowe, immigrant environmental activists from the United States. Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth t ...

activists staged a protest at the site. The last nuclear test explosion was in 1990 (also the last for the entire Soviet Union and Russia). The Ministry for Atomic Energy

Ministry for Atomic Energy of the Russian Federation and Federal Agency on Atomic Energy (or Rosatom), were a Russian federal executive body in 1992–2008 (as Federal Ministry in 1992–2004 and as Federal Agency in 2004–2008).

The Min ...

has performed a series of subcritical

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fissi ...

underwater nuclear experiments near Matochkin Shar each autumn since 1998. These tests reportedly involve up to of weapons-grade plutonium.

In October 2012, it was reported that Russia would resume subcritical nuclear testing at "Zone B". In Spring 2013, construction of what would become a new tunnel and four buildings was initiated near the ''Severny'' settlement, west-northwest to the Mount Lazarev.

Geography and geology

Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

, and the interior is mountainous throughout. It is separated from the mainland by the Kara Strait. Novaya Zemlya consists of two major islands, separated by the narrow Matochkin Strait, as well as a number of smaller islands. The two main islands are:

* Severny (Northern), which has a large ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

Ice caps are not constrained by topographical feat ...

, the Severny Island ice cap, as well as many active glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s.

* Yuzhny (Southern), which is largely unglaciated

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

and has a tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

landscape.Novaya Zemlya in:

The coast of Novaya Zemlya is very indented, and it is the area with the largest number of fjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Germany, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Icel ...

s in the Russian Federation. Novaya Zemlya separates the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian terr ...

from the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea (russian: Ка́рское мо́ре, ''Karskoye more'') is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipel ...

. The total area is about . The highest mountain is located on the Northern island and is 1,547 meters (5,075 ft) high.

Compared to other regions that were under large ice sheets during the last glacial period, Novaya Zemlya shows relatively little isostatic rebound. Possibly this is indebted to a counter-effect created by the growth of glaciers during the last few thousand years.

Geology

The geology of Novaya Zemlya is dominated by a largeanticlinal Anticlinal may refer to:

*Anticline, in structural geology, an anticline is a fold that is convex up and has its oldest beds at its core.

*Anticlinal, in stereochemistry, a torsion angle between 90° to 150°, and –90° to –150°; see Alkane_st ...

structure that forms an extension of the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

. The geology is primarily formed of Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

sedimentary rocks, including both carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate ...

and siliciclastic rocks spanning the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ...

to Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

, ranging from deep marine turbidites and flysch to shallow marine and terrestrial sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

s and reef limestones. Small areas of late Neoproterozoic (~600 mya) granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

and associated metasedimentary rocks are also exposed.

Environment

Theecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

of Novaya Zemlya is influenced by its severe climate, but the region nevertheless supports a diversity of biota. One of the most notable species present is the polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a hypercarnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the largest extant bear spec ...

, whose population in the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian terr ...

region is genetically distinct from other polar bear subpopulations.

Climate

Novaya Zemlya has a maritime-influenced variety of a tundra climate ( Köppen ''ET''). Due to some effect from theGulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the Unit ...

and its offshore position, winters are a lot less severe than in inland areas on a lot lower latitudes in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

, but instead last up to eight months a year. The milder waters to its west delays the onset of sea ice and causes vast seasonal lag

Seasonal lag is the phenomenon whereby the date of maximum average air temperature at a geographical location on a planet is delayed until some time after the date of maximum insolation (i.e. the summer solstice). This also applies to the mini ...

in shoulder seasons. Due to latitudinal differences, the temperatures and daylight varies quite a bit throughout the archipelago, with the Malye Karmakuly station being located in the southern part. Novaya Zemlya is cloudy in general, but snowfall and rainfall is relatively scarce for being a maritime location. Even so, glaciers dominate the northern interior and there is strong snow accumulation each winter due to the length of the season.

Polar bears enter human-inhabited areas more frequently than previously, which has been attributed to climate change. Global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

reduces sea ice, forcing the bears to come inland to find food. In February 2019, a mass migration

Mass migration refers to the migration of large groups of people from one geographical area to another. Mass migration is distinguished from individual or small-scale migration; and also from seasonal migration, which may occur on a regular basis ...

occurred in the northeastern portion of Novaya Zemlya. Dozens of polar bears were seen entering homes, public buildings, and inhabited areas, so Arkhangelsk region authorities declared a state of emergency on Saturday, February 16, 2019.

In creative works

*Gerrit de Veer

Gerrit de Veer (–) was a Dutch officer on Willem Barentsz' second and third voyages of 1595 and 1596 respectively, in search of the Northeast passage.

De Veer kept a diary of the voyages and in 1597, was the first person to observe and record ...

, ''Nova Zembla'', written 1598, published 1996

* Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ...

refers to Nova Zembla in the Preface to the New Essays on Human Understanding, saying that observations there establish that it is not always true that within the passage of twenty-four hours day turns into night and night into day.

* Vladimir Nabokov:

** "The Refrigerator Awakes" (1942), line 27

** In '' Pale Fire'' (1962), Kinbote's home country is named Zembla, and references to Novaya Zembla are made throughout the novel.

* In Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer who is best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., an ...

's ''The Living Daylights'' (1966), Agent 272 is holed up in Novaya Zemlya.

* Clive Cussler

Clive Eric Cussler (July 15, 1931 – February 24, 2020) was an American adventure novelist and underwater explorer. His thriller novels, many featuring the character Dirk Pitt, have reached ''The New York Times'' fiction best-seller list ...

's '' Raise the Titanic!'' (1976), features a U.S. plan to recover a rare element vital to protecting the U.S. in the Cold War, an element found on Novaya Zemlya (where a U.S. spy and a Soviet guard clash), but now believed to be in the wreck of the RMS ''Titanic''.

* Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

, 1833, Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is an 1831 novel by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 – Augus ...

, Book II, Chapter Nine

* Laurence Sterne, 1761, ''The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Book III'', Chapter Twenty

* Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

:

** "The Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bri ...

" (1728), line 74: "Here gay description Egypt glads with showers,/Or gives to Zembla fruits, to Barca flowers..."

** " An Essay on Man" (1733-1734), epistle 2, part 5: "...But where the extreme of vice, was ne’er agreed:/Ask where’s the north? at York, ’tis on the Tweed;/In Scotland, at the Orcades; and there,/At Greenland, Zembla, or the Lord knows where."

* Thomas Köner – ''Novaya Zemlya'', 2012 album on Touch Music

Touch (sometimes mistakenly written 'Touch Records' and sometimes written Touch Music, which is technically the publishing side of the company) is a British audio-visual organisation, operating the Touch label. Touch was founded in 1982 by Jon ...

* Edward Gorey

Edward St. John Gorey (February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer, Tony Award-winning costume designer, and artist, noted for his own illustrated books as well as cover art and illustration for books by other writers. Hi ...

- The Broken Spoke

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

Cycling cards from the pen of Dogear Wryde. One shows 3 contestants in the annual Trans-Novaya Zemlya Bicycle Race.

* The 1998 video game '' Delta Force'' featured several missions set on Novaya Zemlya.

See also

*List of fjords of Russia

This is a list of the most important fjords of the Russian Federation. Fjords

In spite of the vastness of the Arctic coastlines of the Russian Federation there are relatively few fjords in Russia. Fjords are circumscribed to certain areas only; ...

* List of islands of Russia

* Novaya Zemlya effect

*Gusinaya Zemlya

The Gusinaya Zemlya (russian: Гусиная Земля means Goose Land) is a peninsula in the western portion of Yuzhny Island located in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It is the biggest peninsula on the archipelago Novaya Zemlya. It protrudes into ...

* ''Novaya Zemlya'' (2008 film)

* ''Nova Zembla'' (2011 film)

*Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

*Gora Severny Nunatak

Gora Severny or Gora Severnyy Nunatak (russian: Гора Северный Нунатак) is a nunatak in Novaya Zemlya. It is one of the very few nunataks of the Russian Federation. Administratively it falls under the Arkhangelsk Oblast.

Geogra ...

* Mezhdusharsky Island

References

Notes

Sources

* * * *Further reading

*External links

*Novaya Zemlya information portal

(global security).

* ttp://www.rozenbergps.com/index.php?frame=boek.php&item=295 Rozenberg Publishers – Climate and glacial history of the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago, Russian Arctic

Nuclear tests in Novaya Zemlya

International Atomic Energy Agency Department of Nuclear Safety and Security.

Испытание чистой водородной бомбы мощностью 50 млн тонн

declassified

Rosatom

Rosatom, ( rus, Росатом, p=rɐsˈatəm}) also known as Rosatom State Nuclear Energy Corporation, the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom or Rosatom State Corporation, is a Russian state corporation headquartered in Moscow that special ...

historical video of the RDS-220, or Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, 50 megatonne hydrogen bomb test on 30 October 1961. at 8:55–9:30. 20 August 2020.

{{Authority control

Archipelagoes of the Arctic Ocean

Archipelagoes of the Kara Sea

Islands of the Barents Sea

Archipelagoes of Arkhangelsk Oblast

Russian nuclear test sites