Norwich Castle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of

Norwich Castle was founded by

Norwich Castle was founded by

The castle provided sanctuary to Jews fleeing the violence that erupted against them across East Anglia in Lent 1190, and which reached Norwich on 6 February (

The castle provided sanctuary to Jews fleeing the violence that erupted against them across East Anglia in Lent 1190, and which reached Norwich on 6 February (

The castle was bought by the city of Norwich to be used as a museum. The conversion was undertaken by

The castle was bought by the city of Norwich to be used as a museum. The conversion was undertaken by

Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

, in the English county of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

. William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

(1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqu ...

. The castle was used as a gaol from 1220 to 1887. In 1894 the Norwich Museum moved to Norwich Castle. The museum and art gallery holds significant objects from the region, especially works of art, archaeological finds and natural history specimens.

The historic national importance of the Norwich Castle site was recognised in 1915 with its listing as a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and ...

. The castle buildings, including the keep, attached gothic style gatehouse and former prison wings, were given Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

status in 1954. The castle is one of the city's twelve heritage sites.

History

Norwich Castle was founded by

Norwich Castle was founded by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

some time between 1066 and 1075 and originally took the form of a motte and bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy t ...

. Early in 1067, William embarked on a campaign to subjugate East Anglia, and according to military historian

Military history is the study of armed conflict in the history of humanity, and its impact on the societies, cultures and economies thereof, as well as the resulting changes to local and international relationships.

Professional historians no ...

R. Allen Brown it was probably around this time that the castle was founded. The earliest recorded incident at the castle is in 1075, when it was besieged by troops loyal to William to put down a rebellion known as the Revolt of the Earls

The Revolt of the Earls in 1075 was a rebellion of three earls against William I of England (William the Conqueror). It was the last serious act of resistance against William in the Norman Conquest.

Cause

The revolt was caused by the king's refu ...

, co-led by Ralph de Gael

Ralph de Gaël (otherwise Ralph de Guader, Ralph Wader or Radulf Waders or Ralf Waiet or Rodulfo de Waiet; before 1042c. 1100) was the Earl of East Anglia (Norfolk and Suffolk) and Lord of Gaël and Montfort (''Seigneur de Gaël et Montfort'') ...

, Earl of Norfolk. Ralph went abroad to try and rally support from the Danes leaving his wife Emma in charge of the garrison. The support failed to materialise and the rebellion was put down. The siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

lasted three months and ended when Emma secured promises that she and her garrison would be unharmed and given safe passage out of the country.

Norwich is one of 48 castles mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086. Estimates suggest that between 17 and 113 houses were destroyed in the building of the castle. Excavations in the late 1970s discovered that the castle bailey was built over a Saxon cemetery. The historian Robert Liddiard remarks that "to glance at the urban landscape of Norwich, Durham or Lincoln is to be forcibly reminded of the impact of the Norman invasion". Until the construction of Orford Castle

Orford Castle is a castle in Orford in the English county of Suffolk, northeast of Ipswich, with views over Orford Ness. It was built between 1165 and 1173 by Henry II of England to consolidate royal power in the region. The well-preserved ke ...

in the mid-12th century under Henry II, Norwich was the only major royal castle in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

.

About the year 1100, the motte was made higher and the surrounding ditch deepened. The stone keep, which stands today, was built on the south west part of the motte between 1094 and 1121. The keep internally had two floors. The entrance was to the upper floor on the eastern side, accessed via an external stone stairway to a forebuilding which became known as Bigod Tower. An area of land surrounding the castle, known as the Castle Fee was immediately brought under royal control, probably for defensive purposes.

During the Revolt of 1173–1174, in which Henry II's sons rebelled and started a civil war, Norwich Castle was put in a state of readiness. Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, one of the more powerful earls, joined the revolt against Henry. Bigod landed 318 Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

soldiers in England in May 1174 and with 500 of his own men advanced on and captured Norwich Castle. Fourteen prisoners were held for ransom. When peace was restored later that year, Norwich was returned to royal control.

The castle provided sanctuary to Jews fleeing the violence that erupted against them across East Anglia in Lent 1190, and which reached Norwich on 6 February (

The castle provided sanctuary to Jews fleeing the violence that erupted against them across East Anglia in Lent 1190, and which reached Norwich on 6 February (Shrove Tuesday

Shrove Tuesday is the day before Ash Wednesday (the first day of Lent), observed in many Christian countries through participating in confession and absolution, the ritual burning of the previous year's Holy Week palms, finalizing one's Lenten ...

). Those Jews unable to find safety inside the castle were massacred.

The Pipe Rolls, records of royal expenditure, note that repairs were carried out at the castle in 1156–1158 and 1204–1205.

The castle as a prison

Parts of Norwich castle were used as aprison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

from an early stage. Sometimes the earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particu ...

in charge of a royal castle refused to allow the sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

to imprison convicted criminals therein, even though it had been customary to do so. In Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

's reign, an Act of Parliament was passed that gave sheriffs control over the prisons within royal castles. From this time, Norwich castle became the public gaol of the county of Norfolk. The king retained ownership of the castle and continued to appoint a constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

to look after it in his name.

The prison reformer John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

visited six times between 1774 and 1782. He recorded the highest number of inmates at 53; split between felons

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resul ...

and debtors. Howard described an ''upper gaol'' with ten cells, a ''low gaol'' and a dungeon restricted to male felons. He was especially critical of the limited separate facilities for women prisoners.

John Soane rebuilt the prison between 1789 and 1793. The interior walls of the keep were removed and cells for the male felons built. The debtors and women prisoners were accommodated in a new building adjoining the east side of the keep. This building incorporated but obscured the traditional entrance to the keep, the Bigod Tower. Soane’s design was heavily criticised by antiquarian and architect William Wilkins (1751–1815) in his essay in ''Archaeologia'' published by The Society of Antiquarians in 1796 Wilkins continued by slating the gutted interior as

In the 18th century, the castle mound was being used by the city's inhabitants as a soil quarry and rubbish dump. Norwich Justices of the Peace petitioned the House of Commons for the fee simple

In English law, a fee simple or fee simple absolute is an estate in land, a form of freehold ownership. A "fee" is a vested, inheritable, present possessory interest in land. A "fee simple" is real property held without limit of time (i.e., pe ...

of the castle, shirehall and surrounding grounds to be vested in them. This was granted by Act of Parliament on 12 July 1806, thereby ending more than 700 years of royal ownership. The authorities soon deemed Soane's prison inadequate and it was extensively remodelled by Wilkins's son, also named William Wilkins. The building work was completed by 1827. Models and plans of the site show that Wilkins retained Soane's U-shape structure within the keep but demolished Soane's adjoining building and the 1749 rebuilt Elizabethan Shirehall or Sessions House on the north side of the keep. Prisoner accommodation was extended across the top of the castle mound by new wings radiating from a central gaoler's house. A new Shirehall was designed by Wilkins in Tudor style and built at the north east foot of the castle hill in Market Avenue. Prisoners would be escorted from the castle cells, down spiral stairs and along a foot tunnel to the crown court in the shirehall.

The castle ceased to be used as a gaol in 1887, following the opening of HMP Norwich on a site adjacent to the Britannia Barracks at Mousehold Heath.

Notable executions

Robert Kett A wall plaque placed at the entrance to the Museum in 1949 commemorates the 400th anniversary of the execution of Robert Kett. The plaque reads Kett and his brother William were accused ofhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

as leaders of a peasant revolt now known as Kett's Rebellion. After capture in Norfolk the brothers were held at the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and indicted. A special commission of oyer and terminer found both guilty and they were brought back to Norfolk for execution; Robert in Norwich and William in Wymondham. On 7 December 1549 at the behest of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

Robert was 'drawn' from the Guildhall to the Castle and taken up to the battlements on the west face to be hanged in chains

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, executioner's block, impalement stake, hanging gallows, or related scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of crimi ...

from a gibbet. A figurative roundel by sculptor James Woodford

James Arthur Woodford (1893–1976) was an English sculptor. His works include sets of bronze doors for the headquarters of the Royal Institute of British Architects and Norwich City Hall; the Queen's Beasts, originally made for the Coronation i ...

that decorates the central bronze entrance door to Norwich City Hall

Norwich City Hall is an Art Deco building completed in 1938 which houses the city hall for the city of Norwich, East Anglia, in Eastern England. It is one of the Norwich 12, a collection of twelve heritage buildings in Norwich deemed of part ...

depicts the hanging.

James Rush

James Blomfield (or Bloomfield) Rush was hanged at the Castle for the double murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the c ...

of Norwich Recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

, Isaac Jermy and his son at Stanfield Hall near Wymondham on 28 November 1848. The crime, trial and execution excited national as well as local interest. Rush was held in the Castle gaol from early December. His trial took place at the Norwich Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ...

and a guilty verdict was pronounced on 4 April 1849. The convicted felon was marched to the scaffold at noon on 21 April 1849 and despatched by hangman William Calcraft

William Calcraft (11 October 1800 – 13 December 1879) was a 19th-century English hangman, one of the most prolific of British executioners. It is estimated in his 45-year career he carried out 450 executions. A cobbler by trade, Ca ...

in front of thousands of spectators.

Conversion to museum and art gallery

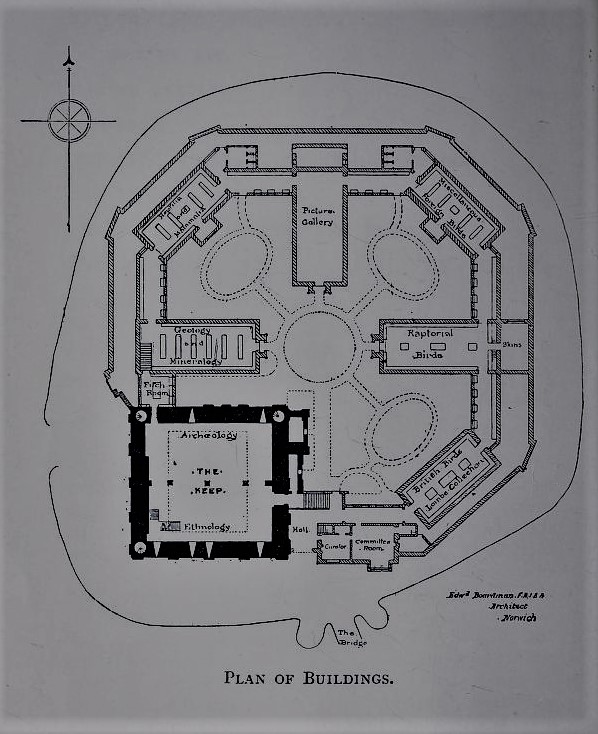

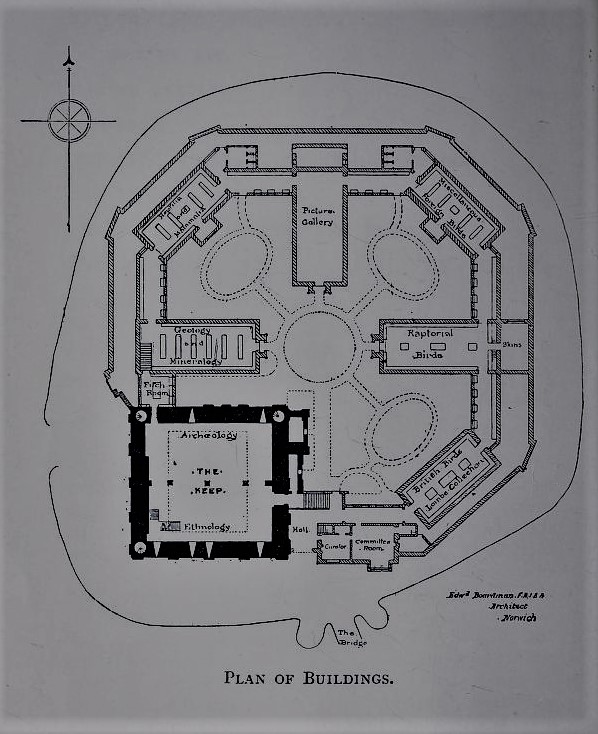

The castle was bought by the city of Norwich to be used as a museum. The conversion was undertaken by

The castle was bought by the city of Norwich to be used as a museum. The conversion was undertaken by Edward Boardman

Edward Boardman (1833–1910) was a Norwich born architect. He succeeded John Brown as the most successful Norwich architect in the second half of the 19th century. The museum was officially opened by the

The outer shell of the keep was extensively repaired in 1835–1839 by the architect Anthony Salvin.

The outer shell of the keep was extensively repaired in 1835–1839 by the architect Anthony Salvin.

The castle remains a museum and art gallery and still contains many of its first exhibits. The museum's fine art collection includes costumes, textiles, jewellery, glass, ceramics and silverware, and a large display of

The castle remains a museum and art gallery and still contains many of its first exhibits. The museum's fine art collection includes costumes, textiles, jewellery, glass, ceramics and silverware, and a large display of

BBC, retrieved 11 April 2015

''The Paston Treasure'' is a painting commissioned around 1663 either by Sir William Paston (1610–1663), or by his son

''The Paston Treasure'' is a painting commissioned around 1663 either by Sir William Paston (1610–1663), or by his son  The Happisburgh hand axe is made of

The Happisburgh hand axe is made of  The unique Anglo-Saxon

The unique Anglo-Saxon  Also known as neck-rings,

Also known as neck-rings,

Official siteInformation about Norwich Castle

by the BBC {{authority control Museums in Norwich Art museums and galleries in Norfolk Castles in Norfolk Prisons in Norfolk Grade I listed buildings in Norfolk Archaeological museums in England Decorative arts museums in England Egyptological collections in England Natural history museums in England Prison museums in the United Kingdom Grade I listed castles Defunct prisons in England Motte-and-bailey castles Debtors' prisons

Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are r ...

and Duchess of York

Duchess of York is the principal courtesy title held by the wife of the duke of York. Three of the eleven dukes of York either did not marry or had already assumed the throne prior to marriage, whilst two of the dukes married twice, therefore t ...

on 23rd October 1894.

Architecture

G. T. Clark

Colonel George Thomas Clark (26 May 1809 – 31 January 1898) was a British surgeon and engineer. He was particularly associated with the management of the Dowlais Iron Company. He was also an antiquary and historian of Glamorgan.

Biography

...

, a 19th-century antiquary

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifacts, archaeological and historic si ...

and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

, described Norwich's great tower as "the most highly ornamented keep in England". It was originally faced with Caen stone over a flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

core. The keep is some by and high, and is of the hall-keep type, entered at first floor level through an external structure called the Bigod Tower. The exterior is decorated with blank arcading. Castle Rising

Castle Rising is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is situated some north-east of the town of King's Lynn and west of the city of Norwich. The River Babingley skirts the north of the village separating C ...

, also in Norfolk, is the only other comparable keep in this respect. Internally, the keep has been gutted so that nothing remains of its medieval layout. The uncertainty surrounding the keep's arrangement has led to scholarly debate. What is agreed on is that it had a complex domestic arrangement, with a kitchen, chapel, a two-storey high hall, and 16 latrines. The original Norman bridge over the inner ditch was replaced in around 1825.

Refacing of the keep

The outer shell of the keep was extensively repaired in 1835–1839 by the architect Anthony Salvin.

The outer shell of the keep was extensively repaired in 1835–1839 by the architect Anthony Salvin. Stonemason

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, ...

James Watson completely refaced the keep with Bath stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of ...

, faithfully reproducing the original ornamentation. The etcher

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

and watercolourist Edward Thomas Daniell was one of the vociferous opponents of the refacing. A letter he wrote published in the ''Norwich Mercury'' in August 1830 referred to the "scandalous re-facing of the ancient keep". Although Daniell was living in London during this period, letters to his friends the artist Henry Ninham and the botanist Dawson Turner reveal the extent of his opposition. In a letter to Turner, Daniell wrote, "I have had a very beautiful drawing made of it, and I mean to etch it the size of the drawing. I can only say that if my etching be half as much like the castle, or half as good as the drawing, it will be more like, than anything yet done, of that very beautiful relic." To Ninham he wrote, "Show me by a plan, how high they have got pulling down, and enable me to judge whether even now in the eleventh hour, any good can be done; and I in return will just inform you, how I stand with regard to my plate. It stands precisely as it did when I left Norwich." His etching of the old keep, however, was never completed.

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery

The castle remains a museum and art gallery and still contains many of its first exhibits. The museum's fine art collection includes costumes, textiles, jewellery, glass, ceramics and silverware, and a large display of

The castle remains a museum and art gallery and still contains many of its first exhibits. The museum's fine art collection includes costumes, textiles, jewellery, glass, ceramics and silverware, and a large display of ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain, ...

teapots. The fine art galleries feature works by the early 19th century Norwich School of painters as well as English watercolour paintings, Dutch landscapes and modern British paintings from the 17th to 20th centuries. The castle also houses a good collection of the work of the Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

artist Peter Tillemans. Other galleries include Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as ()), was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. She ...

and the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened ...

(including the Harford Farm Brooch

The Harford Farm Brooch is a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon disk brooch. The brooch was originally made in Kent and was found along with a number of other artifacts during an excavation of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Harford Farm in Norfolk. The brooch ...

) and Natural History which displays the Fountaine–Neimy butterfly collection. An unusual artefact is the needlework by Lorina Bulwer

Lorina Bulwer (1838 – 5 March 1912) was a British needleworker. She was placed in a workhouse at Great Yarmouth at the age of 55 and there she created several pieces of needlework which have been featured on BBCTV and which can now be found in ...

at the turn of the twentieth century whilst she was confined in a workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

. The work has featured on BBC television.BBC Documentary 2015 - Antiques Roadshow Detectives 2 Lorina BulwerBBC, retrieved 11 April 2015

Exhibit highlights

''The Paston Treasure'' is a painting commissioned around 1663 either by Sir William Paston (1610–1663), or by his son

''The Paston Treasure'' is a painting commissioned around 1663 either by Sir William Paston (1610–1663), or by his son Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

(1631–1683). The identity of the artist is unknown, however it is likely that it was a Dutch artist working in a studio at the principal residence of the Pastons at Oxnead

Oxnead is a lost settlement and former civil parish, now in the parish of Brampton, in the Broadland district, in the county of Norfolk, England. It is roughly three miles south-east of Aylsham. It now consists mostly of St Michael's Church and ...

. The artwork can be placed within the mid-seventeenth century Dutch still life

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, bo ...

tradition, with elements that conform to the genre of vanitas. Still life paintings usually feature one or two objects which are artists' stock items, included only for their symbolism. On the other hand, the majority of the objects represented in ''The Paston Treasure'' were all real, as they correspond to an existing item in the inventories of the Pastons'. Therefore, it was not exclusively commissioned as a ''memento mori'', but also as a record for the family's wealth and own collection and perhaps commemorative of the death of family member, William Paston.

In 2018, the painting formed the centre piece of an exhibition curated by Francesca Vanke, ''The Paston Treasure: Riches & Rarities of the Known World''. The exhibition reunited the painting with some of the objects depicted for the first time in nearly three hundred years.

The Happisburgh hand axe is made of

The Happisburgh hand axe is made of flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

, and measures 12.2 cm × 7.8 cm. The discovery of this Lower Palaeolithic hand axe

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history, yet there is no academic consensus on what they were used for. It is made from stone, usually flint or ...

in 2000 along the Norfolk coast at Happisburgh

Happisburgh () is a village civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is on the coast, to the east of a north–south road, the B1159 from Bacton on the coast to Stalham. It is a nucleated village. The nearest substantial to ...

transformed our understanding of early human occupation in Britain. Dated and shown to be 500,000 years old, it is amongst the oldest handaxes ever discovered in the UK. Analysis of pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametop ...

in the silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

allowed the archaeologists to build a picture of temperate woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (se ...

with the existence of pine, alder, oak, elm and hornbeam trees in evidence at the time the handaxe was made.

The Cavalry Parade Helmet and Visor was found in the River Wensum at Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Ho ...

in 1947 and 1950 respectively. The items, of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

origin, date to the first half of the third century CE. They are an important testimony of the presence of Roman army personnel in central Norfolk during the later period of the Roman occupation. The helmet is made from a single sheet of gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

, highly decorated as to represent a feathered eagle's head on the crest, foliate-tailed beasts on either side and a plain triangular front panel with feather borders on either side at the top, with the lower ends terminating in birds' heads. The visor mask complements the helmet by carrying similar repoussé decoration, depicting Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

on one side and Victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitutes ...

on the other. These two objects are not a fitting pair, although they can be considered together as each would have originally had been coupled with a similar complementary object.

ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain, ...

figurine now known as Spong Man was found in 1979 in Spong Hill. The figure is shown sat on a chair decorated with incised panelling and is leaning forwards with head in hands wearing a round flat hat. It is likely to have once sat on the lid of a pagan funerary urn

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape or ...

and is a unique object in North Western Europe. Although it is labelled as a man, its gender is unclear, as there are no distinctive anatomic details. Exactly why this figurine was created is still a mystery. It is the earliest Anglo-Saxon three-dimensional figure ever found. It may be a representation of a deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

whose identity is now lost, but it is still a great artifact that reminds us how little we know about religion in this early migration period across northern Europe.

Also known as neck-rings,

Also known as neck-rings, torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

s were a characteristic kind of jewel used in the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

across Europe. They would have been worn by prominent people within society as a symbol of status and power. The rare tubular gold torc known as the Gold Tubular Torc came from the Snettisham Treasure. It was found in 1948 at Snettisham

Snettisham is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is located near the west coast of Norfolk, some south of the seaside resort of Hunstanton, north of the town of King's Lynn and northwest of the city of Norwic ...

, alongside a large number of other torcs, carefully disposed in the ground, confirming that burial rituals had great significance within the people of Late Iron Age Norfolk.

Also known as ''The Seven Sorrows of Mary'', the ''Ashwellthorpe Triptych'' has significant connections with South Norfolk and its long trading tradition with Holland. This Flemish altarpiece was commissioned by the Norfolk family of the Knyvettes of Ashwellthorpe. Christopher Knyvettes was sent by King Henry VIII to the Netherlands in 1512, when he commissioned this painting to Master of the Legend of the Magdalen. Both Christopher and his wife Catherina are represented kneeling to Mary, mother of Jesus

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

in the foreground of the composition, showing their religious devotion and wealth.

Dragons in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

are famous through the legend of Saint George

Saint George ( Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldie ...

, however, they have always been particular important in Norwich since the medieval period. The Norwich Snapdragon was made to reflect the civil power and wealth of the city within Norfolk and was used during a procession which combined the celebration of the city's saint and the installation of the new major of the town. The Snapdragon at the Norwich Castle, known as Snap, is the last complete example of the civic snapdragon. Like all others, it was built to contain one person, its body is made of basketwork, painted with gold and red scales over a green body and red underside, while the person's legs were hidden within a canvas 'skirt'.

''Norwich River: Afternoon'' by the Norwich School of Painters artist John Crome. The Norwich Society of Artists was founded in 1803 by Crome and Robert Ladbrooke

Robert Ladbrooke (1768 – 11 October 1842) was an English landscape painter who, along with John Crome, founded the Norwich School of painters. His sons Henry Ladbrooke and John Berney Ladbrooke were also associated with the Norwich School.

E ...

and brought together professional painters and drawing masters such as John Sell Cotman

John Sell Cotman (16 May 1782 – 24 July 1842) was an English marine and landscape painter, etcher, illustrator, author and a leading member of the Norwich School of painters.

Born in Norwich, the son of a silk merchant and lace dealer, C ...

, James Stark, George Vincent as well as other talented amateur artists, who were often inspired by the East Anglian landscape, and were influenced by Dutch landscape painters. This oil on canvas is considered one of the finest works made by Crome. It depicts the River Wensum, near New Mills, at St Martin's Oak, close to where the artist lived, in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

.

The Norfolk Regiment First World War Casualty Book is a unique graphic record of the Norfolk Regiment's participation in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. It records details of more than 15,000 soldiers from the regular and service battalions in 1914 to their return home in 1919. Each entry of the book contains the soldier's name, service number, battalion and details of their health. It also records those who perished in action.

Part of a quartet of rare examples of English medieval art, the stained-glass roundel depicting December is an example of the Norwich School of stained-glass. It shows clear Flemish influences, and it is possible that it has been made by one of the Norwich Strangers, immigrants of the sixteenth century from the Low Countries. It is thought to have been made for the Major Thomas Pykerell's house. originally there would have been twelve roundels depicting the Labours of The Months, a popular pageant in Norwich during that period. This roundel in particular depicts the King of Christmas. Of the original twelve only four now survive, depicting December, September, probably March and either April or November.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Official site

by the BBC {{authority control Museums in Norwich Art museums and galleries in Norfolk Castles in Norfolk Prisons in Norfolk Grade I listed buildings in Norfolk Archaeological museums in England Decorative arts museums in England Egyptological collections in England Natural history museums in England Prison museums in the United Kingdom Grade I listed castles Defunct prisons in England Motte-and-bailey castles Debtors' prisons