Norwegian Americans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norwegian Americans ( nb, Norskamerikanere, nn, Norskamerikanarar) are

The Netherlands, and especially the cities of

The Netherlands, and especially the cities of

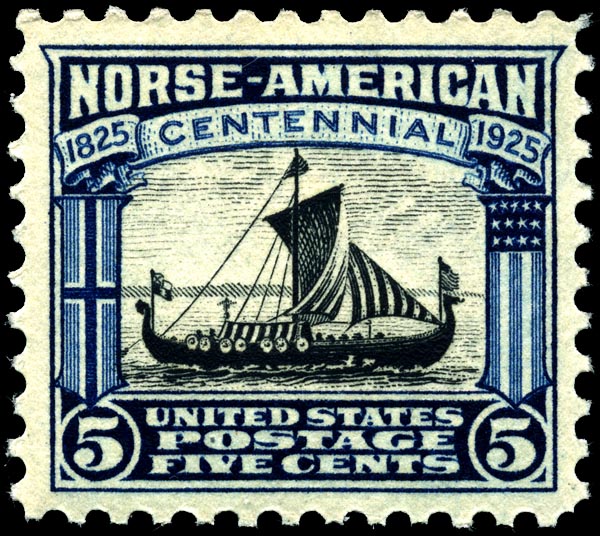

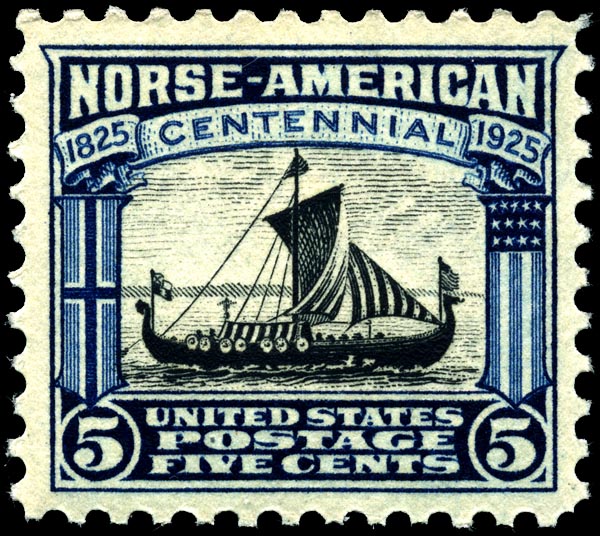

Between 1825 and 1925, more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to North America—about one-third of Norway's population with the majority immigrating to the US, and lesser numbers immigrating to the Dominion of Canada. With the exception of

Between 1825 and 1925, more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to North America—about one-third of Norway's population with the majority immigrating to the US, and lesser numbers immigrating to the Dominion of Canada. With the exception of

Beginning in 1836, Norwegian immigrants arrived in significant numbers annually. From the early "slooper" settlement in

Beginning in 1836, Norwegian immigrants arrived in significant numbers annually. From the early "slooper" settlement in

Norwegian Americans cultivated bonds with

Norwegian Americans cultivated bonds with

Today, the traditions practiced by Norwegian Americans are distinct from those practiced in modern-day Norway. Norwegian Americans are primarily descendants of 19th or early 20th century

Today, the traditions practiced by Norwegian Americans are distinct from those practiced in modern-day Norway. Norwegian Americans are primarily descendants of 19th or early 20th century  There are a number of museums commemorating the Norwegian-American immigrant experience.

There are a number of museums commemorating the Norwegian-American immigrant experience.

File:Emigrantkirka på Sletta.jpg, Lutheran church on Sletta, Radøy, built 1908 to 1922 in

In entertainment, Sigrid Gurie, "the siren of the fjords," starred in numerous motion pictures in the 1930s and 1940s. Other Hollywood actors and personalities with one Norwegian parent or grandparent include James Arness,

In entertainment, Sigrid Gurie, "the siren of the fjords," starred in numerous motion pictures in the 1930s and 1940s. Other Hollywood actors and personalities with one Norwegian parent or grandparent include James Arness,

Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine.

Report of Count Carl Lewenhaupt on Swedish-Norwegian Immigration in 1870

''Swedish Pioneer Historical Quarterly.'' 30(1): pp. 5–24. — Swedish diplomat provides a wealth of factual detail on immigrants.

Vesterheim in Red, White and Blue: The Hyphenated Norwegian-American and Regional Identity in the Pacific Northwest, 1890–1950

. (Dissertation. Washington State University, 2018). * Jacobs, Henry Eyster (1893). '' A History of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States.'' New York: Christian Literature Company. * Joranger, Terje Mikael Hasle (2019). "The Creation of a Norwegian-American Identity in the USA." ''Journal of Migration History''. 5(3): pp. 489–511. * Lovoll, Odd S. (2014). Riggs, Thomas (ed.).

Norwegian Americans

" ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America''. Vol 3 (3rd ed.) vol. 3. Gale. pp. 343–357. * Lovoll, Odd S. (2010). ''Norwegian Newspapers in America: Connecting Norway and the New Land'' . Minnesota Historical Society Press. — discusses more than 280 Norwegian-language papers, both short-lived and successful, founded after 1847. * Mathiesen, Henrik Olav (2014). "Belonging in the Midwest: Norwegian Americans and the Process of Attachment, ca. 1830–1860," ''American Nineteenth Century History''. 15(2): pp. 119–46. * Munch, Peter A. (1979). "Authority and Freedom: Controversy in Norwegian-American Congregations"''.'' '' Norwegian-American Studies''. 28. *Nelson, E. Clifford, and Eugene L. Fevold (1960) ''The Lutheran Church among Norwegian Americans: A History of the Evangelical Lutheran Church.'' Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House. 2 Vols. * Nelson, O. N. (1904). '' History of the Scandinavians and Successful Scandinavians in the United States''. Minneapolis: O. N. Nelson & Co. * Norlie, Olaf M. (1925). ''History of the Norwegian People in America.'' Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House. * Olson, Gary D. (2011). "Norwegian Immigrants in Early Sioux Falls: A Demographic Profile". ''Norwegian-American Studies.'' 36: pp 45–84. * Qualey, Carlton C. (1938). ''Norwegian Settlement in the United States.'' Norwegian-American Historical Association. * Rygg, Andreas Nilsen (1941). ''Norwegians in New York, 1825—1925.'' Brooklyn, N.Y.: Norwegian News Co. *Thaler, Peter (1998). ''Norwegian Minds--American Dreams: Ethnic Activism among Norwegian-American Intellectuals.'' Newark and London: University of Delaware Press. * Woods, Fred E., and Nicholas J. Evans (2002)

'Latter-day Saint Scandinavian Migration through Hull, England, 1852–1894'

''BYU Studies.'' 41(4): pp. 75–102.

Norwegian Embassy official website in the United States

��General information about Norway, news and events of interest to Americans U.S. Census Bureau statistics:

Norwegian population data

��Page hosted by Mongabay.com

Number of language speakers, including Norwegian

Associations/societies:

Daughters of Norway

– organization dedicated to preserving Norwegian immigrant heritage

— United States Congressional Caucus promoting Norwegian-American relations, founded by Norwegian-American congressmen

Norse Federation ''(Nordmanns-Forbundet)''

– Founded in 1907; seeks to strengthen cultural as well as personal ties with Norway

Norwegian-American Bygdelagenes Fellesraad

– umbrella organization for Norwegian-American bygdelags or lags in North America

– promotes trade and goodwill and to foster business, financial and professional interest between Norway and the United States of America

Norwegian-American Foundation

– Foundation sponsoring educational and cultural initiatives based on donor advised funds and contributions

Information on famous Americans, past and present, who are readily associated with their Norwegian ancestry

Norwegian-American Historical Association

— private membership organization dedicated to locating, collecting preserving and interpreting the Norwegian-American experience

– organization dedicated to the Norwegian American culture

Sons of Norway

– organization dedicated to preserving and promoting Norwegian-American heritage and culture

Sons of Norway Vennekretsen

– organization dedicated to preserving and promoting Norwegian heritage and culture in Atlanta, Georgia Museums:

– located on highway 71 northeast of Ottawa, Illinois

Norwegian American Genealogical Center & Naeseth Library

– Norwegian and Norwegian Americang Genealogy. Collection includes bygdebøker, family histories, Norwegian church records, Norwegian American Lutheran church records, cemetery transcripts, transcripts of ship passenger lists, obituaries and more.

– Norwegian Genealogy: List of Reference Sources

Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum

– Exhibitions and collections, genealogy and Civil War databases, etc. {{European Americans

Americans

Americans are the citizens and nationals of the United States of America.; ; Although direct citizens and nationals make up the majority of Americans, many dual citizens, expatriates, and permanent residents could also legally claim Ame ...

with ancestral roots in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

. Norwegian immigrants went to the United States primarily in the latter half of the 19th century and the first few decades of the 20th century. There are more than 4.5 million Norwegian Americans, according to the 2021 U.S. census,; most live in the Upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

and on the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S ...

.

Immigration

Viking-era exploration

Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the ...

from Greenland and Iceland were the first Europeans to reach North America. Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, Leiv Eiriksson, or Leif Ericson, ; Modern Icelandic: ; Norwegian: ''Leiv Eiriksson'' also known as Leif the Lucky (), was a Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to have set foot on continental Nort ...

reached North America via Norse settlements in Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

around the year 1000. Norse settlers from Greenland founded the settlement of L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit. Meadows Cove) is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the C ...

and Point Rosee

Point Rosee (French: ''Pointe Rosée''), previously known as Stormy Point, is a headland near Codroy at the southwest end of the island of Newfoundland, on the Atlantic coast of Canada.

In 2014, archaeologist Sarah Parcak, using near-infrared ...

in Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

, in what is now Newfoundland, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. These settlers failed to establish a permanent settlement because of conflicts with indigenous people and within the Norse community.

Colonial settlement

The Netherlands, and especially the cities of

The Netherlands, and especially the cities of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

and Hoorn

Hoorn () is a city and municipality in the northwest of the Netherlands, in the province of North Holland. It is the largest town and the traditional capital of the region of West Friesland. Hoorn is located on the Markermeer, 20 kilometers ...

, had strong commercial ties with the coastal lumber trade of Norway during the 17th century and many Norwegians immigrated to Amsterdam. Some of them settled in Dutch colonies, although never in large numbers. There were also Norwegian settlers in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in the first half of the 18th century, upstate New York in the latter half of the same century, and in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

during both halves.

During the colonial period, Norwegian immigrants often joined the Dutch seeking opportunities for trade and a new life in America. The Dutch often took Norwegians with them to the New World for their sailing expertise. There was a Norwegian presence in New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

in the early part of the 17th century. Hans Hansen Bergen Hans Hansen Bergen (–1654) was one of the earliest settlers of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, and one of the few from Scandinavia. He was a native of Bergen, Norway. Hans Hansen Bergen was a shipwright who served as overseer of an early tob ...

, a native of Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

, Norway, was one of the earliest settlers of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, having immigrated in 1633. Another early Norwegian settler, Albert Andriessen Bradt, arrived in New Amsterdam in 1637.

Approximately 60 people had settled in the Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

area before the region was taken over by the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

in 1664. The total number of Norwegians that settled in New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva ...

is not known. In the period that followed, many of the original Norwegian settlers in the area remained, including the family of Pieter Van Brugh, a colonial mayor of Albany

From its formal chartering on 22 July 1686 until 1779, the mayors of Albany, New York, were appointed by the royal governor of New York, per the provisions of the original city charter, issued by Governor Thomas Dongan.

From 1779 until 1839, may ...

, who was the grandson of early Norwegian immigrants.

19th century

Many immigrants during the early 1800s sought religious freedom. From the mid-1800s however, the driving forces behind Norwegian immigration to the United States were agricultural disasters which led topoverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse

, from the European Potato Failure of the 1840s to the Famine of 1866–68

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompani ...

. The also put farmers out of work and pushed them to seek employment in a more industrialized America.

Religious migration

The earliest immigrants from Norway to America emigrated mostly for religious motives, especially as members of theReligious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

or as Haugeans. To a great extent, this early emigration from Norway was born out of religious persecution, especially for Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

s and a local religious group, the Haugeans.

Organized Norwegian immigration to North America began in 1825, when several dozen Norwegians left Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

bound for North America on the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

'' Restauration'' (often called the "Norse ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, ...

''"). Under the leadership of Cleng Peerson

Cleng Peerson (17 May 1783 – 16 December 1865) was a Norwegian emigrant to the United States; his voyage in 1824 was the precursor for the boat load of 52 Norwegian emigrants in the following year. That boat load was a precursor for the main ...

, the '' Restauration'' left Stavanger in July 1825 and ferried six families on a 14-week journey. The ship landed in New York City, where it was at first impounded for exceeding its passenger limit. After intervention from President John Quincy Adams, the passengers moved on to settle in Kendall, New York

Kendall is a town in Orleans County, just west of the town of Hamlin in Monroe County, in New York State, United States. The population of Kendall was 2,724 at the 2010 census. The Town of Kendall is in the northeast corner of Orleans County and ...

with the help of Andreas Stangeland, witnessing the opening of the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing ...

en route. After making the journey to Kendall, Cleng Peerson became a traveling emissary for Norwegian immigrants and died in a Norwegian Settlement near Cranfills Gap, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

in 1865. The descendants of these immigrants are referred to as "sloopers", in reference to the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

ship that brought them from Norway. Many of the 1825 immigrants moved on from the Kendall Settlement in the mid-1830s, settling in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. These "Sloopers" gave impetus to the westward movement of Norwegians

Norwegians ( no, nordmenn) are a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians a ...

by founding a settlement in the Fox River area of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

. A small urban colony of Norwegians had its genesis in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

at about the same time.

Organized immigration

While about 65 Norwegians emigrated via Sweden and elsewhere in the intervening years, no emigrant ships left Norway for the New World until the 1836 departures of the ''Den Norske Klippe'' and ''Norden''. In 1837, a group of immigrants fromTinn

Tinn is a municipality in Telemark in the county of Vestfold og Telemark in Norway. It is part of the traditional regions of Upper Telemark and Øst-Telemark. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Rjukan.

The parish of ...

emigrated via Gothenburg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, Göteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the Västra Götaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has ...

to the Fox River Settlement, near present-day Sheridan, Illinois. It was the writings of Ole Rynning, who traveled to the U.S. on the ''Ægir'' in 1837 that energized Norwegian immigration, however.

Throughout much of the latter part of the 19th century and into the 20th century, a vast majority of Norwegian emigration to both the United States and Canada followed a route commonly shared by most Swedish, Danish and Finnish emigrants of the period, being via England by means of the monopoly established by the leading shipping lines of Great Britain, primarily the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

and the Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival Corporation & plc#Carnival United Kingdom, Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its ...

, both of which operated chiefly out of Liverpool, England

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

. These lines negotiated with smaller 'feeder lines', primarily the Wilson Line, which was based out of the port city of Hull on England's east coast, to provide emigrants with passage from port cities such as Christiania (present-day Oslo), Bergen and Trondheim to England via Hull. Steamship companies such as Cunard and White Star included fares for passage on these feeder ship in their overall ticket prices, along with railway fares for passage between Hull and Liverpool and temporary accommodations in numerous hotels owned by the shipping lines in port cities such as Liverpool.

Most Norwegian emigrants bound for the United States entered the country through New York City, with smaller numbers coming through other eastern ports such as Boston and Philadelphia. Other shipping lines such as the Canadian Pacific Line, which operated chiefly out of Liverpool, and the Glasgow-based Anchor Line operated routes to ports in eastern Canada, primarily Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

and Halifax. Because Canadian-bound routes were slightly shorter, lines which disembarked at Canadian ports often provided quicker passages and cheaper fares. The Canadian route offered many advantages to the emigrant over traveling to the USA directly. "They moved on from Quebec both by rail and by steamer for another thousand or more miles (1,600 km) for a steerage fare of slightly less than $9.00." Steamers from Quebec, Canada brought them to Toronto, Canada then the immigrants often traveled by rail for 93 miles to Collingwood, Ontario, Canada on Lake Huron, from where steamers transported them across Lake Michigan to Chicago, Milwaukee and Green Bay. Not until the start of the 20th century did Norwegians accept Canada as a land of the second chance. This was also true of the many American-Norwegians who moved to Canada seeking homesteads and new economic opportunities. By 1921, one-third of all Norwegians in Canada had been born in the U.S.

Between 1825 and 1925, more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to North America—about one-third of Norway's population with the majority immigrating to the US, and lesser numbers immigrating to the Dominion of Canada. With the exception of

Between 1825 and 1925, more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to North America—about one-third of Norway's population with the majority immigrating to the US, and lesser numbers immigrating to the Dominion of Canada. With the exception of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, no single country contributed a larger percentage of its population to the United States than Norway. Data from the U.S. Office of Immigration statistics of the number of Norwegians obtaining lawful permanent resident status in the US from 1870 to 2016 highlights two peaks in the migration flow, the first one in the 1880s, and the second one in the first decade of the 20th century. It also shows an abrupt decrease after 1929, during the economic crisis of the 1930s.

Settlement

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, Norwegian pioneers followed the general spread of population northwestward into Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

remained the center of Norwegian American activity up until the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, a war in which a number of Norwegian Americans fought for the Union, such as in the 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment. In the 1850s Norwegian land seekers began moving into both Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, and serious migration to the Dakotas

The Dakotas is a collective term for the U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota. It has been used historically to describe the Dakota Territory, and is still used for the collective heritage, culture, geography, fauna, sociology, econo ...

was underway by the 1870s.

Norwegian immigration through the years was predominantly motivated by economic concerns. Compounded by crop failures, Norwegian agricultural resources were unable to keep up with population growth, and the Homestead Act of 1862

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of ...

promised fertile, flat land. As a result, settlement trended westward with each passing year. The majority of Norwegian agrarian settlements developed in the northern region of the so-called Homestead Act Triangle between the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and the Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

rivers. Early Norwegian settlements were in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Illinois, but moved westward into Wisconsin, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, and the Dakotas. Later waves of Norwegian immigration went to the Western states such as Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

through missionary efforts which gained Norwegian and Swedish converts to Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects o ...

. Additionally, craftsmen also immigrated to a larger, more diverse market. Until recently, there was a Norwegian area in Sunset Park, Brooklyn

Sunset Park is a neighborhood in the southwestern part of the borough of Brooklyn in New York City, bounded by Park Slope and Green-Wood Cemetery to the north, Borough Park to the east, Bay Ridge to the south, and Upper New York Bay to the ...

originally populated by Norwegian craftsmen.

The upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

became home to most immigrants. In 1910 almost 80 percent of the one million or more Norwegian Americans lived in that part of the United States. In 1990, 51.7 percent of the Norwegian American population lived in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. At that time, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

had the largest Norwegian American population and Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

functioned as a hub for Norwegian American secular and religious activities.

In the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

, the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected m ...

region, and especially the city of Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

, became another center of immigrant life. Enclaves of Norwegian immigrants emerged as well in greater Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

, and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. After Minnesota, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

had the most Norwegians in 1990, followed by California, Washington, and North Dakota.

Cultural identity

19th century

In a letter fromChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

dated November 9, 1855, Elling Haaland from Stavanger, Norway, assured his relatives back home that "of all nations Norwegians are those who are most favored by Americans." Svein Nilsson, a Norwegian-American journalist recorded that "A newcomer from Norway who arrives here will be surprised indeed to find in the heart of the country, more than a thousand miles from his landing place, a town where language and way of life so unmistakably remind him of his native land."

This sentiment was expressed frequently as the immigrants attempted to seek acceptance and negotiate entrance into the new society. In their segregated farming communities, Norwegians

Norwegians ( no, nordmenn) are a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians a ...

were spared direct prejudice and might indeed have been viewed as a welcome ingredient in a region's development. Still, a sense of inferiority was inherent in their position. The immigrants were occasionally referred to as "guests" in the United States and they were not immune to condescending and disparaging attitudes by old-stock Americans. Economic adaptation required a certain amount of interaction with a larger commercial environment, from working for an American farmer to doing business with the seed dealer, the banker, and the elevator operator. Products had to be grown and sold—all of which pulled Norwegian farmers into social contact with their American neighbors.

Norwegian-American debating societies provided opportunities for immigrants to discuss and debate issues of the day in an atmosphere conducive to learning while also developing skills useful in American life. Beginning in 1889, both the ''Wig Debate Society'' and ''Forward Debate Society'', located in Minnesota, hosted weekly debates. Many topics were discussed including voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

, women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

, and racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

. These societies helped to develop friendship and understanding.

In places like Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Seattle, Norwegian-Americans interacted with the multi-cultural environment of the city while constructing a complex ethnic community that met the needs of its members. It might be said that a Scandinavian melting pot existed in the urban setting among Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes, evidenced in residential and occupational patterns, in political mobilization, and in public commemoration. Inter-marriage promoted inter-ethnic assimilation. There are no longer any Norwegian immigrant enclaves or neighborhoods in America's great cities. Beginning in the 1920s, Norwegian-Americans increasingly became suburban.

20th century

Norwegian Americans cultivated bonds with

Norwegian Americans cultivated bonds with Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

, sending gifts home often and offering aid during natural disasters and other hardships in Norway. Relief in the form of collected funds was forthcoming without delay. Only during conflicts within the Union between Sweden and Norway

Sweden and Norway or Sweden–Norway ( sv, Svensk-norska unionen; no, Den svensk-norske union(en)), officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and known as the United Kingdoms, was a personal union of the separate kingdoms of Swede ...

, however, did Norwegian Americans become involved directly in the political life of Norway. In the 1880s they formed societies to assist Norwegian liberals, collecting money to assist rifle clubs in Norway should the political conflict between liberals and conservatives call for arms. The ongoing tensions between Sweden and Norway and Norway's humiliating retreat in 1895 fueled nationalism and created anguish. Norwegian Americans raised money to strengthen Norway's military defenses. The unilateral declaration by Norway on June 7, 1905, to dissolve its union with Sweden yielded a new holiday of patriotic celebration.

In American popular culture, Norwegian Americans were the central characters in the popular CBS network television series, ''Mama

Mama(s) or Mamma or Momma may refer to:

Roles

*Mother, a female parent

* Mama-san, in Japan and East Asia, a woman in a position of authority

*Mamas, a name for female associates of the Hells Angels

Places

* Mama, Russia, an urban-type settlemen ...

'' (1949–1956). Set in San Francisco around 1900, the weekly program focused on working-class family life. They also form the background to Garrison Keillor

Gary Edward "Garrison" Keillor (; born August 7, 1942) is an American author, singer, humorist, voice actor, and radio personality. He created the Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) show ''A Prairie Home Companion'' (called ''Garrison Keillor's Radi ...

's " Lake Wobegon" series of novels as well as ''A Prairie Home Companion

''A Prairie Home Companion'' is a weekly radio variety show created and hosted by Garrison Keillor that aired live from 1974 to 2016. In 2016, musician Chris Thile took over as host, and the successor show was eventually renamed '' Live from ...

'', a radio variety show that contains much humorous material from the "Norwegian American Midwest".

According to a 2018 paper, Norwegian immigrants who lived in large ethnic enclaves in the United States in the 1910 and 1920 "had lower occupational earnings, were more likely to be in farming occupations, and were less likely to be in white-collar occupations."

Traditions

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

and rural Norwegians, and the traditions which these immigrants brought with them represented a specific segment of the Norwegian population and cultural period. As these traditions continued to evolve in an American context, they are today divergent from that of modern-day Norway.

Norwegian Americans actively celebrate and maintain their heritage in many ways. Much of these traditions center upon Lutheran-Evangelical church communities. Other organizations, such as the Sons and Daughters of Norway and the Chicago Norske Klub also serve to preserve their ethnic heritage. Culinary customs (e.g., ''lutefisk

''Lutefisk'' ( Norwegian, in Northern and parts of Central Norway, in Southern Norway; sv, lutfisk ; fi, lipeäkala ; literally " lye fish") is dried whitefish (normally cod, but ling and burbot are also used). It is made from aged sto ...

'' and '' lefse''), national dress (''bunad

''Bunad'' (, plural: ''bunader''/''bunadar'') is a Norwegian umbrella term encompassing, in its broadest sense, a range of both traditional rural clothes (mostly dating to the 18th and 19th centuries) as well as modern 20th-century folk costume ...

''), and Norwegian holidays (''Syttende Mai

Constitution Day is the national day of Norway and is an official public holiday observed on 17 May each year. Among Norwegians, the day is referred to as ''Syttende Mai'' ("Seventeenth of May"), ''Nasjonaldagen'' ("National Day"), or ''Grunnlo ...

'') are also popular. Some regional festivals celebrate Norwegian heritage, predominantly in areas with a high density of Norwegian Americans, such as Norsk Høstfest

Norsk Høstfest (Norwegian language: "''Norwegian Autumn Festival''") is an annual festival held each fall in Minot, North Dakota, US. It is North America's largest Scandinavian festival.

History

The event is held on the North Dakota State Fair gr ...

(English'':'' ''Norwegian Autumn Festival''), an annual festival held in Minot, North Dakota

Minot ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Ward County, North Dakota, United States, in the state's north-central region. It is most widely known for the Air Force base approximately north of the city. With a population of 48,377 at the 2 ...

. In 1925, the Norse-American Centennial celebration was held at the Minnesota State Fair.

A number of towns in the United States, particularly in the Upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

, are known for their display of Norwegian heritage, including: Stoughton, Wisconsin

Stoughton is a city in Dane County, Wisconsin, United States. It straddles the Yahara River about 20 miles southeast of the state capital, Madison. Stoughton is part of the Madison Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census, the popula ...

; Sunburg, Minnesota; Ulen, Minnesota

Ulen ( ) is a city in Clay County, Minnesota, Clay County, Minnesota, United States, along the South Branch of the Wild Rice River (Minnesota), Wild Rice River. The population was 476 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

Near this sma ...

; and Westby, Wisconsin

Westby is a city in Vernon County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 2,332 as of the 2020 census. The name "Westby" is a Norwegian name and literally translates to "Western city".

History

Westby was named after general store owner an ...

. Starbuck, Minnesota

Starbuck is a city in Pope County, Minnesota, Pope County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 1,365 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The city is on the western shore of Lake Minnewaska (Minnesota), Lake Minnewaska.

Geogra ...

is known to produce the largest lefse in the world. Other regions known for their Norwegian heritage or origins include: Norge, Virginia Norge is an unincorporated community in James City County, Virginia, United States.

Location

Norge is located on the old Richmond-Williamsburg Stage Road, which is U.S. Route 60 in modern times. Interstate 64 was built through the area in the 1970 ...

; Petersburg, Alaska

Petersburg (Tlingit: ''Séet Ká'' or ''Gantiyaakw Séedi'' "Steamboat Channel") is a census-designated place (CDP) in and essentially the borough seat of Petersburg Borough, Alaska, United States. The population was 3,043 at the 2020 census, up ...

; Poulsbo, Washington; and Lapskaus Boulevard

Eighth Avenue is a major street in Brooklyn, New York City. It was formerly an enclave for Norwegians and Norwegian-Americans, who have recently become a minority in the area among the current residents, which include new immigrant colonies, am ...

, the nickname of 8th Avenue in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

.

There are a number of museums commemorating the Norwegian-American immigrant experience.

There are a number of museums commemorating the Norwegian-American immigrant experience. Norskedalen

Norskedalen Nature and Heritage Center is a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving, interpreting, and sharing the Coulee Region's natural environment and cultural heritage. It is near Coon Valley, in La Crosse, and Vernon counties, Wis ...

is a natural and cultural heritage site near Coon Valley, Wisconsin

Coon Valley is a village in Vernon County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 765 at the 2010 census. Coon Valley was hit by the floods ravaging Wisconsin in 2018.

Geography

Coon Valley is located at (43.701628, -91.014083).

Accordi ...

, spread over 440 acres which exhibits the Norwegian immigrant experience of the late 1800s. Little Norway, Wisconsin

Little Norway was a living museum of a Norwegian village located in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. Little Norway consisted of a fully restored farm dating to the mid-19th century. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Little Norway ...

is a living museum of a Norwegian village located in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. The National Nordic Museum in the Ballard, a district Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

heavily settled by Scandinavian immigrants, serves as a community gathering place. The Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum in Decorah, Iowa

Decorah is a city in and the county seat of Winneshiek County, Iowa, United States. The population was 7,587 at the time of the 2020 census. Decorah is located at the intersection of State Highway 9 and U.S. Route 52, and is the largest commun ...

is the largest museum in the United States dedicated to the experiences of a single immigrant population and has an extensive collection of Norwegian-American artifacts. Chapel in the Hills is an exact replica of the Borgund stave church in Norway, located in Rapid City, South Dakota

Rapid City ( lkt, link=no, Mni Lúzahaŋ Otȟúŋwahe; "Swift Water City") is the second most populous city in South Dakota and the county seat of Pennington County. Named after Rapid Creek, where the settlement developed, it is in western S ...

. The church's site also maintains other period typical historical buildings.

Religion

Although today Norway is relatively secular, Norwegian-Americans are among the most religious ethnic groups in the United States, with 90% acknowledging a religious affiliation in 1998. Because membership to theState Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

was mandatory until the 19th century in Norway, all ethnic Norwegians have traditionally been Lutheran. Today, many Norwegian Americans remain Lutheran, though significant numbers converted to other Christian denominations. Some Norwegians immigrated to the United States in hope of practicing other religions freely. A significant number of Norwegian immigrants and their descendants were Methodists concentrated especially in Chicago, with its own theological seminary, while others converted to become Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul com ...

. There were also groups of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

, relating back to "the Sloopers," and Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into sever ...

who joined the trek to the "New Jerusalem" in Salt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, t ...

.

Norwegian Lutheranism

Most Norwegian immigrants to the United States, particularly in the migration wave between the 1860s and early 20th century, were members of theChurch of Norway

The Church of Norway ( nb, Den norske kirke, nn, Den norske kyrkja, se, Norgga girku, sma, Nöörjen gærhkoe) is an evangelical Lutheran denomination of Protestant Christianity and by far the largest Christian church in Norway. The church ...

, an evangelical Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

church established by the Constitution of Norway

nb, Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov

nn, Kongeriket Noregs Grunnlov

, jurisdiction = Kingdom of Norway

, date_created =10 April - 16 May 1814

, date_ratified =16 May 1814

, system =Constitutional monarchy

, ...

. As they settled in their new homeland and forged their own communities, however, Norwegian-American Lutherans diverged from the state church in many ways, forming synods and conferences that ultimately contributed to the present Lutheran establishment in the United States. The Norwegian Lutheran church

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

was a focal point in rural settlements in the Upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

. The congregation became an all-encompassing institution for its members, creating a tight social network that touched all aspects of immigrant life. The force of tradition in religious practice made the church a central institution in the urban environment as well. The severe reality of urban life increased the social role of the church.

The official State Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

in Norway did not extend pastoral care to emigrants and provided no guidance in the formation of new congregations in the United States. The Church of Norway was seen as an integrated part of the Norwegian state administration with no particular responsibility for people outside of Norway, with the exception of sailors and those who remained citizens. As a consequence, no fewer than 14 Lutheran synods were founded by Norwegian immigrants between 1846 and 1900. In 1917 most of the factions reconciled doctrinal differences and organized the Norwegian Lutheran Church in America. It was one of the church bodies that in 1960 formed the American Lutheran Church

The American Lutheran Church (TALC) was a Christian Protestant denomination in the United States and Canada that existed from 1960 to 1987. Its headquarters were in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Upon its formation in 1960, The ALC designated Augsburg ...

, which in 1988 became a constituent part of the newly created Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is a mainline Protestant Lutheran church headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA was officially formed on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three Lutheran church bodies. , it has approxim ...

.

Norwegian Lutheran colleges

Several Lutheran colleges and higher education institutions were founded by Norwegian Americans, which retain a Norwegian lutheran identity today. Luther College, located inDecorah, Iowa

Decorah is a city in and the county seat of Winneshiek County, Iowa, United States. The population was 7,587 at the time of the 2020 census. Decorah is located at the intersection of State Highway 9 and U.S. Route 52, and is the largest commun ...

was founded by Norwegian immigrants in 1861 and is today associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is a mainline Protestant Lutheran church headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA was officially formed on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three Lutheran church bodies. , it has approxim ...

. Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota is also associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is a mainline Protestant Lutheran church headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA was officially formed on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three Lutheran church bodies. , it has approxim ...

and was founded by Norwegian settlers in 1891. Other Norwegian Lutheran colleges include: Augsburg University

Augsburg University is a private university in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is affiliated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. It was founded in 1869 as a Norwegian-American Lutheran seminary known as Augsburg Seminarium. Today, the ...

, Augustana College, Bethany Lutheran College

Bethany Lutheran College (BLC) is a private Christian liberal arts college in Mankato, Minnesota. Founded in 1927, BLC is operated by the Evangelical Lutheran Synod. The campus overlooks the Minnesota River valley in a community of 53,000.

...

, Pacific Lutheran University

Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) is a private Lutheran university in Parkland, Washington. It was founded by Norwegian Lutheran immigrants in 1890. PLU is sponsored by the 580 congregations of Region I of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Ame ...

, St. Olaf College

St. Olaf College is a private liberal arts college in Northfield, Minnesota. It was founded in 1874 by a group of Norwegian-American pastors and farmers led by Pastor Bernt Julius Muus. The college is named after the King and the Patron Saint Olaf ...

, and Waldorf College

Waldorf University is a private for-profit university in Forest City, Iowa. It was founded in 1903 and associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and its predecessors. In 2010, it was sold to Columbia Southern University and beca ...

.

Brampton

Brampton ( or ) is a city in the Canadian province of Ontario. Brampton is a city in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and is a lower-tier municipality within Peel Region. The city has a population of 656,480 as of the 2021 Census, making it t ...

, North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, ...

, and moved as a gift from Norwegian emigrants in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in 1997.

File:St.olaf.kirke.jpg, St. Olaf Kirke

St. Olaf Kirke, commonly referred to as The Rock Church, is a small Lutheran church located outside of Cranfills Gap, Texas, United States, in an unincorporated rural community known as Norse in Bosque County, Texas. The Church is affiliated with ...

, constructed in 1884, in Cranfills Gap, Texas.

File:Church in Irwin, Iowa.jpg, Norwegian Lutheran Church in Irwin, Iowa

Irwin is a city in Shelby County, Iowa, United States, along the West Nishnabotna River. The population was 319 at the time of the 2020 census.

History

The Western Town Lot Company established Irwin in 1881. The town was named for E. W. Irwin, ...

, in 1941.

File:Mindekirken Outside ViewFromSE.jpg, Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origi ...

, built in 1922.

File:ChapelInTheHills3.JPG, Chapel in the Hills, a replica of an historic stave church

A stave church is a medieval wooden Christian church building once common in north-western Europe. The name derives from the building's structure of post and lintel construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing ore-pine posts ar ...

, consecrated in 1969 in Rapid City, South Dakota

Rapid City ( lkt, link=no, Mni Lúzahaŋ Otȟúŋwahe; "Swift Water City") is the second most populous city in South Dakota and the county seat of Pennington County. Named after Rapid Creek, where the settlement developed, it is in western S ...

.

File:Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church, Chicago, Illinois LCCN2011636313.tif, Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church, or '' Minnekirken'', completed in 1912 in Chicago's Logan Square neighborhood.

File:Norway NY One of the oldest Churches in Herkimer County.jpg, Historic Norwegian church in Herkimer County, New York

Herkimer County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 60,139. Its county seat is Herkimer. The county was created in 1791 north of the Mohawk River out of part of Montgomery County. It is named ...

Language usage

Use of theNorwegian language

Norwegian ( no, norsk, links=no ) is a North Germanic language spoken mainly in Norway, where it is an official language. Along with Swedish and Danish, Norwegian forms a dialect continuum of more or less mutually intelligible local and r ...

in the United States was at its peak between 1900 and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, then declined in the 1920s and 1930s. Over one million Americans spoke Norwegian as their primary language from 1900 to World War I, and more than 3,000 Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

churches in the Upper Midwest used Norwegian as their sole language. There were hundreds of Norwegian-language newspapers across the Upper Midwest.

*'' Decorah Posten'' and '' Skandinaven'' were major Norwegian language newspapers.

*''The Northfield Northfield may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Northfield, Aberdeen, Scotland

* Northfield, Edinburgh, Scotland

* Northfield, Birmingham, England

* Northfield (Kettering BC Ward), Northamptonshire, England

United States

* Northfield, Connect ...

Independent'' was another notable newspaper. The editor was Andrew Rowberg, who collected massive numbers of Norwegian births and deaths in U.S. The file he created is now known as The Rowberg File Maintained at St. Olaf College

St. Olaf College is a private liberal arts college in Northfield, Minnesota. It was founded in 1874 by a group of Norwegian-American pastors and farmers led by Pastor Bernt Julius Muus. The college is named after the King and the Patron Saint Olaf ...

, and is commonly used in family research across the US and Norway.

*Over 600,000 homes received at least one Norwegian newspaper in 1910.

However, use of the language declined in part due to the rise of nationalism among the American population during and after World War I. During this period, readership of Norwegian-language publications fell. Norwegian Lutheran churches began to hold their services in English, and the younger generation of Norwegian Americans was encouraged to speak English rather than Norwegian. When Norway itself was liberated from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in 1945, relatively few Norwegian Americans under the age of 40 still spoke Norwegian as their primary language (although many still understood the language). As such, they were not passing the language on to their children, the next generation of Norwegian Americans.

Some sources stated that today there are 81,000 Americans who speak Norwegian as their primary language. According to the US Census however, only 55,475 Americans spoke Norwegian at home as of 2000, and the American Community Survey in 2005 showed that only 39,524 people use the language at home. Still, most Norwegian Americans can speak a common Norwegian with easy words like hello, yes and no. Today, there are still 1,209 people who only understand Norwegian or who do not speak English well in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. In 2000 this figure was 215 for those under 17 years old, whereas it increased to 216 in 2005. For other age groups, the numbers went down. For those who are from 18 to 64 years old, went down from 915 in 2000 to 491 in 2005. For those who are older than 65 years it went drastically down from 890 to 502 in the same period. The Norwegian language is likely to never die out in the U.S. because there is still immigration, of course on a much smaller scale, but they often emigrate to other areas, like Texas, where the number of Norwegian speakers increase.

Many Lutheran colleges that were established by immigrants and people of Norwegian background, such as Luther College in Decorah, Iowa

Decorah is a city in and the county seat of Winneshiek County, Iowa, United States. The population was 7,587 at the time of the 2020 census. Decorah is located at the intersection of State Highway 9 and U.S. Route 52, and is the largest commun ...

, Pacific Lutheran University

Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) is a private Lutheran university in Parkland, Washington. It was founded by Norwegian Lutheran immigrants in 1890. PLU is sponsored by the 580 congregations of Region I of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Ame ...

in Tacoma, Washington

Tacoma ( ) is the county seat of Pierce County, Washington, United States. A port city, it is situated along Washington's Puget Sound, southwest of Seattle, northeast of the state capital, Olympia, and northwest of Mount Rainier National Pa ...

, and St. Olaf College

St. Olaf College is a private liberal arts college in Northfield, Minnesota. It was founded in 1874 by a group of Norwegian-American pastors and farmers led by Pastor Bernt Julius Muus. The college is named after the King and the Patron Saint Olaf ...

in Northfield, Minnesota

Northfield is a city in Dakota and Rice counties in the State of Minnesota. It is mostly in Rice County, with a small portion in Dakota County. The population was 20,790 at the 2020 census.

History

Northfield was platted in 1856 by John W ...

, continue to offer Norwegian majors in their undergraduate programs. Many major American universities, such as the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

, University of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a public research university in Eugene, Oregon. Founded in 1876, the institution is well known for its strong ties to the sports apparel and marketing firm Nike, Inc

Nike, Inc. ( or ) is a ...

, University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

, and the Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universi ...

offer Norwegian as a language within their Germanic language studies programs.

Two Norwegian Lutheran churches in the United States continue to use Norwegian as a primary liturgical language, Mindekirken in Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

and Minnekirken in Chicago. There are also several Norwegian Seaman's Churches in the US that have services in Norwegian. They are located in Houston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, New Orleans, and New York.

Literary writing in Norwegian in North America includes the works of Ole Edvart Rølvaag

Ole Edvart Rølvaag (; Rølvåg in modern Norwegian, Rolvaag in English orthography) (April 22, 1876 – November 5, 1931) was a Norwegian-American novelist and professor who became well known for his writings regarding the Norwegian American imm ...

, whose best-known work ''Giants in the Earth'' ("''I de dage''", literally ''In Those Days'') was published in both English and Norwegian versions. Rølvaag was a professor from 1906 to 1931 at St. Olaf College, where he was also head of the Norwegian studies department beginning in 1916.

Communities by Norwegian speakers

As of 2000, U.S. communities with high percentages of people who use Norwegian language were: # Blair, Wisconsin 8.54% #Westby, Wisconsin

Westby is a city in Vernon County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 2,332 as of the 2020 census. The name "Westby" is a Norwegian name and literally translates to "Western city".

History

Westby was named after general store owner an ...

7.67%

# Northwood, North Dakota

Northwood is a city in Grand Forks County, North Dakota, United States. It is part of the "Grand Forks, ND- MN Metropolitan Statistical Area" or "Greater Grand Forks." The population was 982 at the 2020 census.

History

Northwood was founded in ...

4.41%

# Fertile, Minnesota

Fertile is a city in Polk County, Minnesota, United States. It is part of the Grand Forks ND- MN Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 804 at the 2020 census.

The annual Polk County Fair is held in Fertile and dates to 1900. This ...

4.26%

# Spring Grove, Minnesota

Spring Grove is a city in Houston County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 1,330 at the 2010 census. It is part of the La Crosse-Onalaska, WI-MN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

A post office has been in operation at Spring ...

4.14%

# Mayville, North Dakota

Mayville is a city in Traill County, North Dakota, United States. The population was 1,854 at the 2020 census. which makes Mayville the largest community in Traill County. Mayville was founded in 1881. The city's name remembers May Arnold, the f ...

3.56%

# Strum, Wisconsin 2.86%

# Crosby, North Dakota

Crosby is a city and the county seat of Divide County, North Dakota, United States. The population was 1,065 at the 2020 census.

History

Crosby was founded in 1904 at the end of a Great Northern Railway branch line that began in Berthold ...

2.81%

# Twin Valley, Minnesota 2.54%

# Velva, North Dakota 2.52%

Counties by Norwegian speakers

As of 2000, the ten U.S. counties with the highest percentage of Norwegian language speakers were: #Divide County, North Dakota

Divide County is a county in the U.S. state of North Dakota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 2,195. Its county seat is Crosby.

History

On November 8, 1910, election, the voters of Williams County voters determined that the county ...

2.3%

# Griggs County, North Dakota 2.0%

# Nelson County, North Dakota 2.0%

# Norman County, Minnesota 2.0%

# Traill County, North Dakota 2.0%

# Vernon County, Wisconsin

Vernon County is a county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 30,714. Its county seat is Viroqua.

History

Vernon County was renamed from Bad Ax County on March 22, 1862. Bad Ax County had been created o ...

1.8%

# Steele County, North Dakota 1.6%

# Trempealeau County, Wisconsin 1.6%

# Lac qui Parle County, Minnesota

Lac qui Parle County () is a county in the U.S. state of Minnesota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 6,719. Its county seat is Madison. The largest city in the county is Dawson.

History

The name of the county is French for "Lake ...

1.5%

# Pennington County, Minnesota 1.0%

States by Norwegian speakers

Demographics

Immigrants by year or period

Population by region

Historical population by year

Historical population by state, comparison by census

Notable people

In entertainment, Sigrid Gurie, "the siren of the fjords," starred in numerous motion pictures in the 1930s and 1940s. Other Hollywood actors and personalities with one Norwegian parent or grandparent include James Arness,

In entertainment, Sigrid Gurie, "the siren of the fjords," starred in numerous motion pictures in the 1930s and 1940s. Other Hollywood actors and personalities with one Norwegian parent or grandparent include James Arness, Paris Hilton

Paris Whitney Hilton (born February 17, 1981) is an American media personality, businesswoman, socialite, model, and entertainer. Born in New York City, and raised there and in Beverly Hills, California, she is a great-granddaughter of Conrad ...

, James Cagney

James Francis Cagney Jr. (; July 17, 1899March 30, 1986) was an American actor, dancer and film director. On stage and in film, Cagney was known for his consistently energetic performances, distinctive vocal style, and deadpan comic timing. He ...

, Peter Graves, Tippi Hedren, Lance Henriksen

Lance Henriksen (born May 5, 1940) is an American actor. He is known for his works in various science fiction, action and horror films, such as that of Bishop in the ''Alien'' film franchise, and Frank Black in Fox television series ''Millenn ...

, Celeste Holm

Celeste Holm (April 29, 1917 – July 15, 2012) was an American stage, film and television actress.

Holm won an Academy Award for her performance in Elia Kazan's '' Gentleman's Agreement'' (1947), and was nominated for her roles in ''Come to ...

, Kristanna Loken

Kristanna Loken (born October 8, 1979) is a Norwegian American actress and model. She is known for her roles in the films '' Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines'' (2003), ''BloodRayne'' (2005) and ''Bounty Killer'' (2013) and on the TV series ''P ...

, Robert Mitchum

Robert Charles Durman Mitchum (August 6, 1917 – July 1, 1997) was an American actor. He rose to prominence with an Academy Award nomination for the Best Supporting Actor for ''The Story of G.I. Joe'' (1945), followed by his starring in ...

, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen

Mary-Kate Olsen and Ashley Fuller Olsen (born June 13, 1986), also known as the Olsen twins as a duo, are American fashion designers and former actresses. The twins made their acting debut as infants playing Michelle Tanner on the television s ...

, Elizabeth Olsen, Piper Perabo

Piper Lisa Perabo () (born October 31, 1976) is an American actress. Following her breakthrough in the comedy-drama film '' Coyote Ugly'' (2000), she starred in ''The Prestige'' (2006), ''Angel Has Fallen'' (2019), and as CIA agent Annie Walke ...

, Chris Pratt

Christopher Michael Pratt (born June 21, 1979) is an American actor. He rose to prominence for playing Andy Dwyer in the NBC sitcom '' Parks and Recreation'' (2009–2015). He also appeared in The WB drama series '' Everwood'' (2002–2006) ...

, Priscilla Presley, Michelle Williams, Rainn Wilson

Rainn Percival Dietrich Wilson (born January 20, 1966) is an American actor, comedian, podcaster, producer, and writer. He is best known for his role as Dwight Schrute on the NBC sitcom ''The Office'', for which he earned three consecutive Em ...