Norman Borlaug on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norman Ernest Borlaug (; March 25, 1914September 12, 2009) was an American agronomist who led initiatives worldwide that contributed to the extensive increases in agricultural production termed the

Borlaug was the great-grandchild of Norwegian immigrants to the United States. Ole Olson Dybevig and Solveig Thomasdatter Rinde, of

Borlaug was the great-grandchild of Norwegian immigrants to the United States. Ole Olson Dybevig and Solveig Thomasdatter Rinde, of

An Abundant Harvest: Interview with Norman Borlaug, Recipient, Nobel Peace Prize, 1970

Common Ground, August 12 In July 1944, after rejecting

US201303170850

Borlaug mostly admired the work and personality of Rachel Carson but lamented her Silent Spring, what he saw as its inaccurate portrayal of the effects of DDT, and that it became her best known work. Borlaug retired officially from the position in 1979, but remained a CIMMYT senior

Borlaug said that his first few years in Mexico were difficult. He lacked trained scientists and equipment. Local farmers were hostile towards the wheat program because of serious crop losses from 1939 to 1941 due to stem rust. "It often appeared to me that I had made a dreadful mistake in accepting the position in Mexico," he wrote in the epilogue to his book, ''Norman Borlaug on World Hunger''. He spent the first ten years breeding wheat cultivars resistant to disease, including

Borlaug said that his first few years in Mexico were difficult. He lacked trained scientists and equipment. Local farmers were hostile towards the wheat program because of serious crop losses from 1939 to 1941 due to stem rust. "It often appeared to me that I had made a dreadful mistake in accepting the position in Mexico," he wrote in the epilogue to his book, ''Norman Borlaug on World Hunger''. He spent the first ten years breeding wheat cultivars resistant to disease, including

As an unexpected benefit of the double wheat season, the new breeds did not have problems with photoperiodism. Normally, wheat varieties cannot adapt to new environments, due to the changing periods of sunlight. Borlaug later recalled, "As it worked out, in the north, we were planting when the days were getting shorter, at low elevation and high temperature. Then we'd take the seed from the best plants south and plant it at high elevation, when days were getting longer and there was lots of rain. Soon we had varieties that fit the whole range of conditions. That wasn't supposed to happen by the books". This meant that the project would not need to start separate breeding programs for each geographic region of the planet.

As an unexpected benefit of the double wheat season, the new breeds did not have problems with photoperiodism. Normally, wheat varieties cannot adapt to new environments, due to the changing periods of sunlight. Borlaug later recalled, "As it worked out, in the north, we were planting when the days were getting shorter, at low elevation and high temperature. Then we'd take the seed from the best plants south and plant it at high elevation, when days were getting longer and there was lots of rain. Soon we had varieties that fit the whole range of conditions. That wasn't supposed to happen by the books". This meant that the project would not need to start separate breeding programs for each geographic region of the planet.

In 1961 to 1962, Borlaug's dwarf spring wheat strains were sent for multilocation testing in the International Wheat Rust Nursery, organized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In March 1962, a few of these strains were grown in the fields of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in Pusa, New Delhi, India. In May 1962,

In 1961 to 1962, Borlaug's dwarf spring wheat strains were sent for multilocation testing in the International Wheat Rust Nursery, organized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In March 1962, a few of these strains were grown in the fields of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in Pusa, New Delhi, India. In May 1962,

Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production. These changes in agriculture began in developed countrie ...

. Borlaug was awarded multiple honors for his work, including the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

, the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

and the Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

.

Borlaug received his B.S. in forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

in 1937 and Ph.D. in plant pathology

Plant pathology (also phytopathology) is the scientific study of diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

from the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

in 1942. He took up an agricultural research position with CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known - even in English - by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT for ''Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo'') is a non-profit research-for-development organization that develops im ...

in Mexico, where he developed semi-dwarf, high- yield, disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

-resistant wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

varieties. During the mid-20th century, Borlaug led the introduction of these high-yielding varieties combined with modern agricultural production techniques to Mexico, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

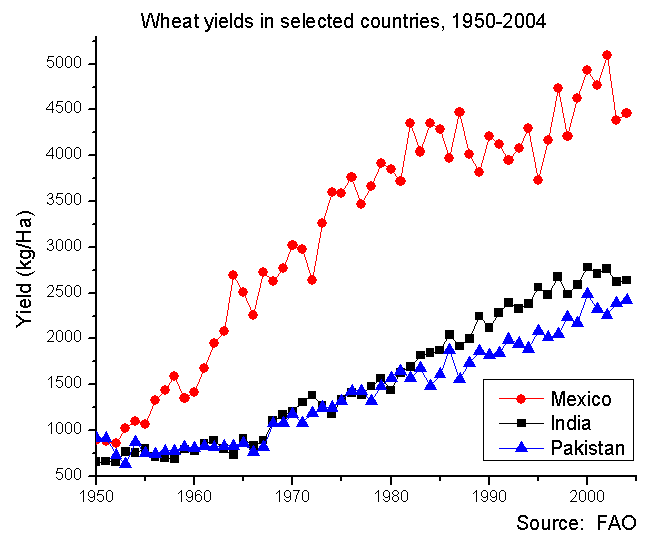

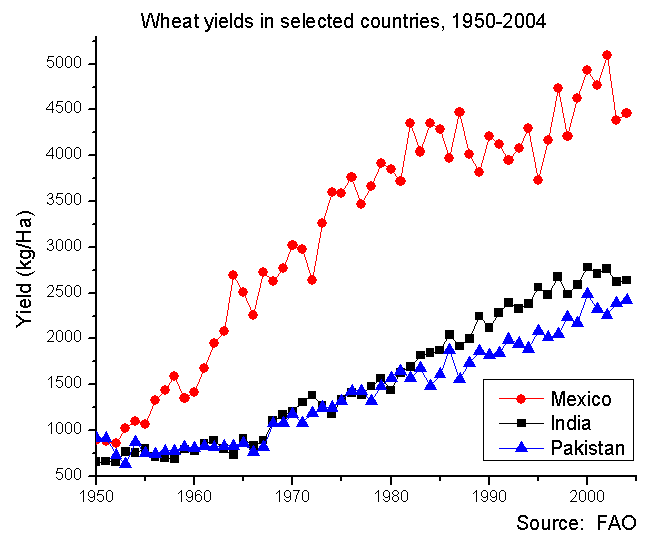

. As a result, Mexico became a net exporter of wheat by 1963. Between 1965 and 1970, wheat yields nearly doubled in Pakistan and India, greatly improving the food security

Food security speaks to the availability of food in a country (or geography) and the ability of individuals within that country (geography) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuffs. According to the United Nations' Committee on World ...

in those nations.

Borlaug was often called "the father of the Green Revolution", and is credited with saving over a billion people worldwide from starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

.The phrase "over a billion lives saved" is often cited by others in reference to Norman Borlaug's work. According to Jan Douglas, executive assistant to the president of the World Food Prize Foundation, the source of this number is Gregg Easterbrook's 1997 article "Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity." The article states that the "form of agriculture that Borlaug preaches may have prevented a billion deaths." He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

in 1970 in recognition of his contributions to world peace through increasing food supply.

Later in his life, he helped apply these methods of increasing food production in Asia and Africa.

Early life, education and family

Borlaug was the great-grandchild of Norwegian immigrants to the United States. Ole Olson Dybevig and Solveig Thomasdatter Rinde, of

Borlaug was the great-grandchild of Norwegian immigrants to the United States. Ole Olson Dybevig and Solveig Thomasdatter Rinde, of Feios

Feios is a village in Vik Municipality in Vestland county, Norway. The village is located on the southern shore of the Sognefjorden, about southeast of the village of Vangsnes and about northwest of the village of Fresvik. The village lies in a ...

, a small village in Vik kommune, Sogn og Fjordane, Norway, emigrated to Dane County, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, in 1854. The family eventually moved to the small Norwegian-American

Norwegian Americans ( nb, Norskamerikanere, nn, Norskamerikanarar) are Americans with ancestral roots in Norway. Norwegian immigrants went to the United States primarily in the latter half of the 19th century and the first few decades of the ...

community of Saude, near Cresco, Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

. There they were members of Saude Lutheran Church, where Norman was both baptized and confirmed.

Borlaug was born to Henry Oliver (1889–1971) and Clara (Vaala) Borlaug (1888–1972) on his grandparents' farm in Saude in 1914, the first of four children. His three sisters were Palma Lillian (Behrens; 1916–2004), Charlotte (Culbert; b. 1919-2012) and Helen (b. 1921). From age seven to nineteen, he worked on the family farm west of Protivin, Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, fishing, hunting, and raising corn, oats, timothy-grass, cattle, pigs and chickens. He attended the one-teacher, one-room New Oregon #8 rural school in Howard County, through eighth grade.

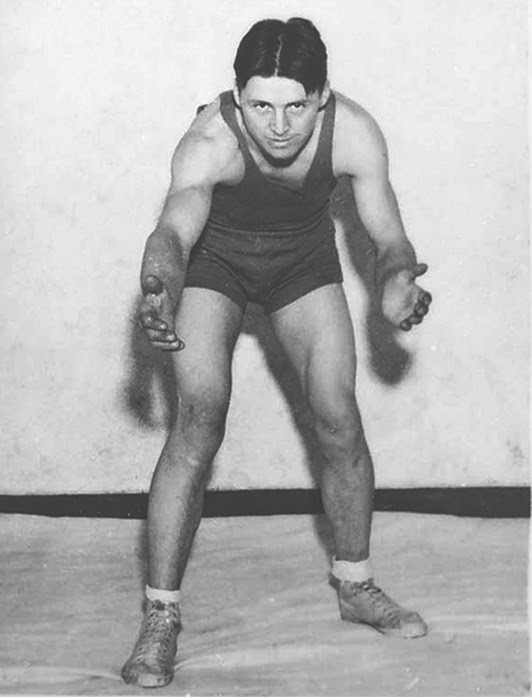

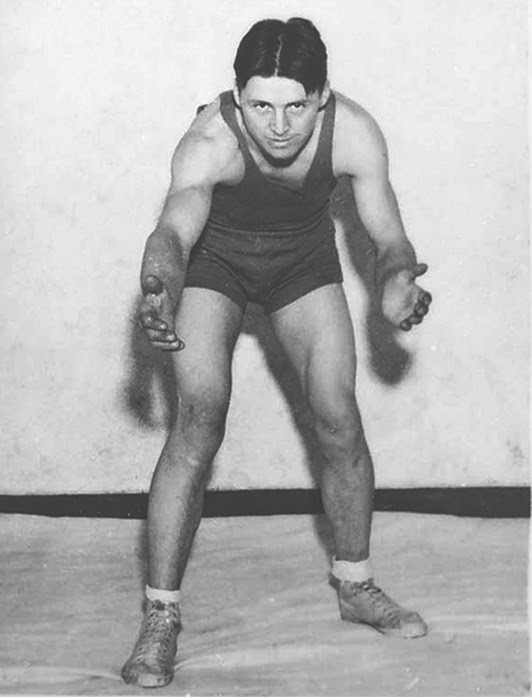

Today, the school building, built in 1865, is owned by the Norman Borlaug Heritage Foundation as part of "Project Borlaug Legacy".State Historical Society of Iowa. 2002. FY03 HRDP/REAP Grant Application Approval Borlaug was a member of the football, baseball and wrestling teams at Cresco High School, where his wrestling coach, Dave Barthelma, continually encouraged him to "give 105%".

Borlaug attributed his decision to leave the farm and pursue further education to his grandfather's urgent encouragement to learn: Nels Olson Borlaug (1859–1935) once told him, "you're wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on." When Borlaug applied for admission to the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

in 1933, he failed its entrance exam, but was accepted at the school's newly created two-year General College. After two quarters, he transferred to the College of Agriculture's forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

program. As a member of University of Minnesota's varsity wrestling team, Borlaug reached the Big Ten

The Big Ten Conference (stylized B1G, formerly the Western Conference and the Big Nine Conference) is the oldest Division I collegiate athletic conference in the United States. Founded as the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representati ...

semifinals, and promoted the sport to Minnesota high schools in exhibition matches all around the state.

Wrestling taught me some valuable lessons ... I always figured I could hold my own against the best in the world. It made me tough. Many times, I drew on that strength. It's an inappropriate crutch perhaps, but that's the way I'm made.University of Minnesota. 2005.To finance his studies, Borlaug put his education on hold periodically to earn some income, as he did in 1935 as a leader in the

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a ...

, working with the unemployed on Federal projects. Many of the people who worked for him were starving. He later recalled, "I saw how food changed them ... All of this left scars on me". From 1935 to 1938, before and after receiving his Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

in forestry in 1937, Borlaug worked for the United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 United States National Forest, national forests and 20 United States Nationa ...

at stations in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

. He spent one summer in the middle fork of Idaho's Salmon River, the most isolated piece of wilderness in the nation at that time.

In the last months of his undergraduate education, Borlaug attended a Sigma Xi

Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society () is a highly prestigious, non-profit honor society for scientists and engineers. Sigma Xi was founded at Cornell University by a junior faculty member and a small group of graduate students in 1886 ...

lecture by Elvin Charles Stakman

Elvin Charles Stakman (May 17, 1885 – January 22, 1979) was an American plant pathologist who was a pioneer of methods of identifying and combatting disease in wheat.

Career

Stakman was the advisor for Margaret Newton, who completed her Docto ...

, a professor and soon-to-be head of the plant pathology

Plant pathology (also phytopathology) is the scientific study of diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, ...

group at the University of Minnesota. The event was a pivot for Borlaug's future. Stakman, in his speech entitled "These Shifty Little Enemies that Destroy our Food Crops", discussed the manifestation of the plant disease rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO( ...

, a parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

fungus

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

that feeds on phytonutrients

Phytochemicals are chemical compounds produced by plants, generally to help them resist fungi, bacteria and plant virus infections, and also consumption by insects and other animals. The name comes . Some phytochemicals have been used as pois ...

in wheat, oats, and barley crops. He had discovered that special plant breeding

Plant breeding is the science of changing the traits of plants in order to produce desired characteristics. It has been used to improve the quality of nutrition in products for humans and animals. The goals of plant breeding are to produce cr ...

methods produced plants resistant to rust. His research greatly interested Borlaug, and when Borlaug's job at the Forest Service was eliminated because of budget

A budget is a calculation play, usually but not always financial, for a defined period, often one year or a month. A budget may include anticipated sales volumes and revenues, resource quantities including time, costs and expenses, environme ...

cuts, he asked Stakman if he should go into forest pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

. Stakman advised him to focus on plant pathology instead. He subsequently enrolled at the university to study plant pathology under Stakman. Borlaug earned a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

degree in 1940, and a Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

in 1942.

Borlaug was a member of the Alpha Gamma Rho

Alpha Gamma Rho (), commonly known as AGR, is a social/professional, agriculture fraternity in the United States, currently with 71 collegiate chapters.

Founding

The fraternity considers the Morrill Act of 1862 to be the instrument of its incept ...

fraternity. While in college, he met his future wife, Margaret Gibson, as he waited tables at a coffee shop in the university's Dinkytown

Dinkytown is a commercial district within the Marcy-Holmes neighborhood in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Centered at 14th Avenue Southeast and 4th Street Southeast, the district contains several city blocks occupied by various small businesses, restau ...

, where the two of them worked. They were married in 1937 and had three children, Norma Jean "Jeanie" Laube, Scotty (who died from spina bifida

Spina bifida (Latin for 'split spine'; SB) is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, men ...

soon after birth), and William; five grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. On March 8, 2007, Margaret Borlaug died at the age of ninety-five, following a fall. They had been married for sixty nine years. Borlaug resided in northern Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

the last years of his life, although his global humanitarian efforts left him with only a few weeks of the year to spend there.

Career

From 1942 to 1944, Borlaug was employed as amicrobiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of para ...

at DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

in Wilmington, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

. It was planned that he would lead research on industrial and agricultural bacteriocides, fungicide

Fungicides are biocidal chemical compounds or biological organisms used to kill parasitic fungi or their spores. A fungistatic inhibits their growth. Fungi can cause serious damage in agriculture, resulting in critical losses of yield, quality ...

s, and preservative

A preservative is a substance or a chemical that is added to products such as food products, beverages, pharmaceutical drugs, paints, biological samples, cosmetics, wood, and many other products to prevent decomposition by microbial growth or b ...

s. However, following the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

Borlaug tried to enlist in the military, but was rejected under wartime labor regulations; his lab was converted to conduct research for the United States armed forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

. One of his first projects was to develop glue that could withstand the warm salt water

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish w ...

of the South Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. The Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

had gained control of the island of Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

, and patrolled the sky and sea by day. The only way for U.S. forces to supply the troops stranded on the island was to approach at night by speedboat, and jettison boxes of canned food and other supplies into the surf to wash ashore. The problem was that the glue holding these containers together disintegrated in saltwater. Within weeks, Borlaug and his colleagues had developed an adhesive that resisted corrosion, allowing food and supplies to reach the stranded Marines. Other tasks included work with camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

; canteen

{{Primary sources, date=February 2007

Canteen is an Australian national support organisation for young people (aged 12–25) living with cancer; including cancer patients, their brothers and sisters, and young people with parents or primary carers ...

disinfectants; DDT to control malaria; and insulation for small electronics.

In 1940, the Avila Camacho administration took office in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. The administration's primary goal for Mexican agriculture was augmenting the nation's industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and economic growth. U.S. Vice President-Elect Henry Wallace, who was instrumental in persuading the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropy, philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, aft ...

to work with the Mexican government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republ ...

in agricultural development, saw Avila Camacho's ambitions as beneficial to U.S. economic and military interests.Wright, Angus 2005. The Death of Ramón González. The Rockefeller Foundation contacted E.C. Stakman and two other leading agronomists. They developed a proposal for a new organization, the Office of Special Studies, as part of the Mexican Government, but directed by the Rockefeller Foundation. It was to be staffed with both Mexican and US scientists, focusing on soil development, maize and wheat production, and plant pathology

Plant pathology (also phytopathology) is the scientific study of diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, ...

.

Stakman chose Dr. Jacob George "Dutch" Harrar as project leader. Harrar immediately set out to hire Borlaug as head of the newly established Cooperative Wheat Research and Production Program in Mexico; Borlaug declined, choosing to finish his war service at DuPont.Davidson, M.G. 1997An Abundant Harvest: Interview with Norman Borlaug, Recipient, Nobel Peace Prize, 1970

Common Ground, August 12 In July 1944, after rejecting

DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

's offer to double his salary, and temporarily leaving behind his pregnant wife and 14-month-old daughter, he flew to Mexico City to head the new program as a geneticist and plant pathologist

Plant pathology (also phytopathology) is the scientific study of diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, oomy ...

.

In 1964, he was made the director of the International Wheat Improvement Program at El Batán, Texcoco, on the eastern fringes of Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

, as part of the newly established Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research's International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center ''(Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo,'' or CIMMYT). Funding for this autonomous international research training institute developed from the Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program was undertaken jointly by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations and the Mexican government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republ ...

.

Besides his work in genetic resistance against crop loss, he felt that pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests. This includes herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, microbicide, fungicide, and ...

s including DDT had more benefits than drawbacks for humanity and advocated publicly for their continued use. He continued to support pesticide use despite the severe public criticism he received for it. AGRIS iUS201303170850

Borlaug mostly admired the work and personality of Rachel Carson but lamented her Silent Spring, what he saw as its inaccurate portrayal of the effects of DDT, and that it became her best known work. Borlaug retired officially from the position in 1979, but remained a CIMMYT senior

consultant

A consultant (from la, consultare "to deliberate") is a professional (also known as ''expert'', ''specialist'', see variations of meaning below) who provides advice and other purposeful activities in an area of specialization.

Consulting servi ...

. In addition to taking up charitable and educational roles, he continued to be involved in plant research at CIMMYT with wheat, triticale, barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

, maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

, and high-altitude sorghum

''Sorghum'' () is a genus of about 25 species of flowering plants in the grass family (Poaceae). Some of these species are grown as cereals for human consumption and some in pastures for animals. One species is grown for grain, while many other ...

.

In 1981, Borlaug became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.

In 1984, Borlaug began teaching and conducting research at Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public university, public, Land-grant university, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M Unive ...

. Eventually he was given the title Distinguished Professor of International Agriculture at the university and the holder of the Eugene Butler Endowed Chair in Agricultural Biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used ...

.

He advocated for agricultural biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used ...

as he had for pesticides in earlier decades: Publicly, knowledgeably, and always despite heavy criticism.

Borlaug remained at A&M until his death in September 2009.

Wheat research in Mexico

The Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program, a joint venture by theRockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropy, philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, aft ...

and the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture, involved research in genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

, plant breeding

Plant breeding is the science of changing the traits of plants in order to produce desired characteristics. It has been used to improve the quality of nutrition in products for humans and animals. The goals of plant breeding are to produce cr ...

, plant pathology, entomology

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as ara ...

, agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

, soil science

Soil science is the study of soil as a natural resource on the surface of the Earth including soil formation, classification and mapping; physical, chemical, biological, and fertility properties of soils; and these properties in relation to ...

, and cereal

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food ...

technology. The goal of the project was to boost wheat production in Mexico, which at the time was importing a large portion of its grain. Plant pathologist George Harrar recruited and assembled the wheat research team in late 1944. The four other members were soil scientist William Colwell; maize breeder Edward Wellhausen; potato breeder John Niederhauser; and Norman Borlaug, all from the United States.Brown, L. R. 1970. Nobel Peace Prize: developer of high-yield wheat receives award (Norman Ernest Borlaug). ''Science'', 30 October 1970;170(957):518–19. During the sixteen years Borlaug remained with the project, he bred a series of remarkably successful high-yield, disease-resistant, semi-dwarf wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

.

Borlaug said that his first few years in Mexico were difficult. He lacked trained scientists and equipment. Local farmers were hostile towards the wheat program because of serious crop losses from 1939 to 1941 due to stem rust. "It often appeared to me that I had made a dreadful mistake in accepting the position in Mexico," he wrote in the epilogue to his book, ''Norman Borlaug on World Hunger''. He spent the first ten years breeding wheat cultivars resistant to disease, including

Borlaug said that his first few years in Mexico were difficult. He lacked trained scientists and equipment. Local farmers were hostile towards the wheat program because of serious crop losses from 1939 to 1941 due to stem rust. "It often appeared to me that I had made a dreadful mistake in accepting the position in Mexico," he wrote in the epilogue to his book, ''Norman Borlaug on World Hunger''. He spent the first ten years breeding wheat cultivars resistant to disease, including rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO( ...

. In that time, his group made 6,000 individual crossings of wheat.University of Minnesota. 2005.

Double harvest season

Initially, Borlaug's work had been concentrated in the central highlands, in the village ofChapingo

Chapingo is a small town located on the outskirts of the city of Texcoco, State of Mexico in central Mexico.

It is located at , about east-northeast of Mexico City International Airport.

Chapingo is most notable as the location of Chapingo Aut ...

near Texcoco, where the problems with rust and poor soil were most prevalent

In epidemiology, prevalence is the proportion of a particular population found to be affected by a medical condition (typically a disease or a risk factor such as smoking or seatbelt use) at a specific time. It is derived by comparing the number o ...

. The village never met their aims. He realized that he could speed up breeding by taking advantage of the country's two growing seasons. In the summer he would breed wheat in the central highlands as usual, then immediately take the seeds north to the Valle del Yaqui research station near Ciudad Obregón

Ciudad Obregón is a city in southern Sonora. It is the state's second largest city after Hermosillo and serves as the municipal seat of Cajeme, as of 2020, the city has a population of 436,484. Ciudad Obregón is south of the state's norther ...

, Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

. The difference in altitudes and temperatures would allow more crops to be grown each year.

Borlaug's boss, George Harrar, was against this expansion. Besides the extra costs of doubling the work, Borlaug's plan went against a then-held principle of agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

that has since been disproved. It was believed that to store energy for germination before being planted, seeds needed a rest period after harvesting. When Harrar vetoed his plan, Borlaug resigned. Elvin Stakman, who was visiting the project, calmed the situation, talking Borlaug into withdrawing his resignation and Harrar into allowing the double wheat season. As of 1945, wheat would then be bred at locations 700 miles (1000 km) apart, 10 degrees apart in latitude, and 8500 feet (2600 m) apart in altitude. This was called "shuttle breeding".

As an unexpected benefit of the double wheat season, the new breeds did not have problems with photoperiodism. Normally, wheat varieties cannot adapt to new environments, due to the changing periods of sunlight. Borlaug later recalled, "As it worked out, in the north, we were planting when the days were getting shorter, at low elevation and high temperature. Then we'd take the seed from the best plants south and plant it at high elevation, when days were getting longer and there was lots of rain. Soon we had varieties that fit the whole range of conditions. That wasn't supposed to happen by the books". This meant that the project would not need to start separate breeding programs for each geographic region of the planet.

As an unexpected benefit of the double wheat season, the new breeds did not have problems with photoperiodism. Normally, wheat varieties cannot adapt to new environments, due to the changing periods of sunlight. Borlaug later recalled, "As it worked out, in the north, we were planting when the days were getting shorter, at low elevation and high temperature. Then we'd take the seed from the best plants south and plant it at high elevation, when days were getting longer and there was lots of rain. Soon we had varieties that fit the whole range of conditions. That wasn't supposed to happen by the books". This meant that the project would not need to start separate breeding programs for each geographic region of the planet.

Disease resistance through varieties of wheat

Becausepurebred

Purebreds are " cultivated varieties" of an animal species achieved through the process of selective breeding. When the lineage of a purebred animal is recorded, that animal is said to be "pedigreed". Purebreds breed true-to-type which means the ...

(genotypically

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

identical) plant varieties often only have one or a few major genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

for disease resistance, and plant diseases such as rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO( ...

are continuously producing new races that can overcome a pure line's resistance, multiple linear lines varieties were developed. Multiline varieties are mixtures of several phenotypically

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

similar pure lines which each have different genes for disease resistance. By having similar heights, flowering and maturity dates, seed colors, and agronomic characteristics, they remain compatible with each other, and do not reduce yields when grown together on the field.

In 1953, Borlaug extended this technique by suggesting that several pure lines with different resistance genes should be developed through backcross methods using one recurrent parent. Backcrossing

Backcrossing is a crossing of a hybrid with one of its parents or an individual genetically similar to its parent, to achieve offspring with a genetic identity closer to that of the parent. It is used in horticulture, animal breeding, and produ ...

involves crossing a hybrid and subsequent generations with a recurrent parent. As a result, the genotype of the backcrossed progeny becomes increasingly similar to that of the recurrent parent. Borlaug's method would allow the various different disease-resistant genes from several donor parents to be transferred into a single recurrent parent. To make sure each line has different resistant genes, each donor parent is used in a separate backcross program. Between five and ten of these lines may then be mixed depending upon the races of pathogen present in the region. As this process is repeated, some lines will become susceptible to the pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

. These lines can easily be replaced with new resistant lines.

As new sources of resistance become available, new lines are developed. In this way, the loss of crops is kept to a minimum, because only one or a few lines become susceptible to a pathogen within a given season, and all other crops are unaffected by the disease. Because the disease would spread more slowly than if the entire population were susceptible, this also reduces the damage to susceptible lines. There is still the possibility that a new race of pathogen will develop to which all lines are susceptible, however."AGB 301: Principles and Methods of Plant Breeding". Tamil Nadu Agricultural University.

Dwarfing

Dwarfing is an important agronomic quality for wheat; dwarf plants produce thick stems. Thecultivars

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture, ...

Borlaug worked with had tall, thin stalks. Taller wheat grasses better compete for sunlight, but tend to collapse under the weight of the extra grain—a trait called lodging—from the rapid growth spurts induced by nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

Borlaug used in the poor soil. To prevent this, he bred wheat to favor shorter, stronger stalks that could better support larger seed heads. In 1953, he acquired a Japanese dwarf variety of wheat called Norin 10 developed by the agronomist Gonjiro Inazuka in Iwate Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu. It is the second-largest Japanese prefecture at , with a population of 1,210,534 (as of October 1, 2020). Iwate Prefecture borders Aomori Prefecture to the north, Akita Prefectu ...

, including ones which had been crossed with a high-yielding American cultivar called Brevor 14 by Orville Vogel Orville Vogel (1907–1991) was an American scientist and wheat breeder whose research made possible the "Green Revolution" in world food production.

Life and career

Orville Alvin Vogel was born in Pilger, Stanton County, Nebraska, one of the four ...

. Norin 10/Brevor 14 is semi-dwarf (one-half to two-thirds the height of standard varieties) and produces more stalks and thus more heads of grain per plant. Also, larger amounts of assimilate were partitioned into the actual grains, further increasing the yield. Borlaug crossbred the semi-dwarf Norin 10/Brevor 14 cultivar with his disease-resistant cultivars to produce wheat varieties that were adapted to tropical and sub-tropical climates.

Borlaug's new semi-dwarf, disease-resistant varieties, called Pitic 62 and Penjamo 62, changed the potential yield of spring wheat dramatically. By 1963, 95% of Mexico's wheat crops used the semi-dwarf varieties developed by Borlaug. That year, the harvest was six times larger than in 1944, the year Borlaug arrived in Mexico. Mexico had become fully self-sufficient in wheat production, and a net exporter of wheat.University of Minnesota. 2005. Four other high-yield varieties were also released, in 1964: Lerma Rojo 64, Siete Cerros, Sonora 64, and Super X.

Expansion to South Asia: the Green Revolution

In 1961 to 1962, Borlaug's dwarf spring wheat strains were sent for multilocation testing in the International Wheat Rust Nursery, organized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In March 1962, a few of these strains were grown in the fields of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in Pusa, New Delhi, India. In May 1962,

In 1961 to 1962, Borlaug's dwarf spring wheat strains were sent for multilocation testing in the International Wheat Rust Nursery, organized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In March 1962, a few of these strains were grown in the fields of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in Pusa, New Delhi, India. In May 1962, M. S. Swaminathan

Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan (born 7 August 1925) is an Indian agronomist, agricultural scientist, plant geneticist, administrator and humanitarian. Swaminathan is a global leader of the green revolution. He has been called the main archit ...

, a member of IARI's wheat program, requested of Dr B. P. Pal, director of IARI, to arrange for the visit of Borlaug to India and to obtain a wide range of dwarf wheat seed possessing the Norin 10 dwarfing genes. The letter was forwarded to the Indian Ministry of Agriculture headed by Shri C. Subramaniam

Chidambaram Subramaniam (commonly known as CS) (30 January 1910 – 7 November 2000), was an Indian politician and independence activist. He served as Minister of Finance and Minister of Defence in the union cabinet. He later served as the Go ...

, which arranged with the Rockefeller Foundation for Borlaug's visit.

In March 1963, the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropy, philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, aft ...

and the Mexican government sent Borlaug and Dr Robert Glenn Anderson to India to continue his work. He supplied 100 kg (220 lb) of seed from each of the four most promising strains and 630 promising selections in advanced generations to the IARI in October 1963, and test plots were subsequently planted at Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

, Ludhiana

Ludhiana ( ) is the most populous and the largest city in the Indian state of Punjab. The city has an estimated population of 1,618,879 2011 census and distributed over , making Ludhiana the most densely populated urban centre in the state. I ...

, Pant Nagar, Kanpur

Kanpur or Cawnpore ( /kɑːnˈpʊər/ pronunciation (help· info)) is an industrial city in the central-western part of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Founded in 1207, Kanpur became one of the most important commercial and military stations ...

, Pune

Pune (; ; also known as Poona, ( the official name from 1818 until 1978) is one of the most important industrial and educational hubs of India, with an estimated population of 7.4 million As of 2021, Pune Metropolitan Region is the largest i ...

and Indore

Indore () is the largest and most populous city in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It serves as the headquarters of both Indore District and Indore Division. It is also considered as an education hub of the state and is the only city to ...

. Anderson stayed as head of the Rockefeller Foundation Wheat Program in New Delhi until 1975.

During the mid-1960s the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

was at war and experienced minor famine and starvation, which was limited partially by the U.S. shipping a fifth of its wheat production to India in 1966 & 1967. The Indian and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

i bureaucracies and the region's cultural opposition to new agricultural techniques initially prevented Borlaug from fulfilling his desire to immediately plant the new wheat strains there. In 1965, as a response to food shortages, Borlaug imported 550 tons of seeds for the government.

Biologist Paul R. Ehrlich wrote in his 1968 bestseller '' The Population Bomb'', "The battle to feed all of humanity is over ... In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now." Ehrlich said, "I have yet to meet anyone familiar with the situation who thinks India will be self-sufficient in food by 1971," and "India couldn't possibly feed two hundred million more people by 1980."

In 1965, after extensive testing, Borlaug's team, under Anderson, began its effort by importing about 450 tons of Lerma Rojo and Sonora 64 semi-dwarf seed varieties: 250 tons went to Pakistan and 200 to India. They encountered many obstacles. Their first shipment of wheat was held up in Mexican customs and so it could not be shipped from the port at Guaymas

Guaymas () is a city in Guaymas Municipality, in the southwest part of the state of Sonora, in northwestern Mexico. The city is south of the state capital of Hermosillo, and from the U.S. border. The municipality is located on the Gulf of Cali ...

in time for proper planting. Instead, it was sent via a 30-truck convoy from Mexico to the U.S. port in Los Angeles, encountering delays at the Mexico–United States border

The Mexico–United States border ( es, frontera Estados Unidos–México) is an international border separating Mexico and the United States, extending from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east. The border trave ...

. Once the convoy entered the U.S., it had to take a detour, as the U.S. National Guard

The National Guard is a state-based military force that becomes part of the reserve components of the United States Army and the United States Air Force when activated for federal missions.Watts riots in Los Angeles. When the seeds reached Los Angeles, a Mexican bank refused to honor Pakistan treasury's payment of US$100,000, because the check contained three misspelled words. Still, the seed was loaded onto a freighter destined for  In Pakistan, wheat yields nearly doubled, from 4.6 million

In Pakistan, wheat yields nearly doubled, from 4.6 million

''Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity''

The Atlantic Monthly. The use of these wheat varieties has also had a substantial effect on production in six

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1970

From ''Nobel Lectures, Peace 1951–1970'', Frederick W. Haberman Ed., Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam His speech repeatedly presented improvements in food production within a sober understanding of the context of

Interview with '' Reason Magazine''. April 2000 Borlaug refuted or dismissed most claims of his critics, but did take certain concerns seriously. He stated that his work has been "a change in the right direction, but it has not transformed the world into a Utopia".Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. 2002. Of environmental lobbyists opposing crop yield improvements, he stated, "some of the environmental lobbyists of the Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are

The SAA is a research and Agricultural extension, extension organization that aims to increase food production in African countries that are struggling with food shortages. "I assumed we'd do a few years of research first," Borlaug later recalled, "but after I saw the terrible circumstances there, I said, 'Let's just start growing'." Soon, Borlaug and the SAA had projects in seven countries. Yields of maize in developed African countries tripled. Yields of wheat,

The SAA is a research and Agricultural extension, extension organization that aims to increase food production in African countries that are struggling with food shortages. "I assumed we'd do a few years of research first," Borlaug later recalled, "but after I saw the terrible circumstances there, I said, 'Let's just start growing'." Soon, Borlaug and the SAA had projects in seven countries. Yields of maize in developed African countries tripled. Yields of wheat,

Sounding the Alarm on Global Stem Rust

, and their work led to the formation of the Global Rust Initiative. In 2008, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the organization was re-named the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative

Food for Thought

Borlaug believed that GMO, genetically modified organisms (GMO) was the only way to increase food production as the world runs out of unused arable land. GMOs were not inherently dangerous "because we've been genetically modifying plants and animals for a long time. Long before we called it science, people were selecting the best breeds." In a review of Borlaug's 2000 publication entitled ''Ending world hunger: the promise of biotechnology and the threat of antiscience zealotry'', the authors argued that Borlaug's warnings were still true in 2010, According to Borlaug, "Africa, the former Soviet republics, and the cerrado are the last frontiers. After they are in use, the world will have no additional sizable blocks of arable land left to put into production, unless you are willing to level whole forests, which you should not do. So, future food-production increases will have to come from higher yields. And though I have no doubt yields will keep going up, whether they can go up enough to feed the population monster is another matter. Unless progress with agricultural yields remains very strong, the next century will experience sheer human misery that, on a numerical scale, will exceed the worst of everything that has come before". Besides increasing the worldwide food supply, early in his career Borlaug stated that taking steps to decrease the rate of population growth will also be necessary to prevent food shortages. In his Nobel Lecture of 1970, Borlaug stated, "Most people still fail to comprehend the magnitude and menace of the 'Population Monster' ... If it continues to increase at the estimated present rate of two percent a year, the world population will reach 6.5 billion by the year 2000. Currently, with each second, or tick of the clock, about 2.2 additional people are added to the world population. The rhythm of increase will accelerate to 2.7, 3.3, and 4.0 for each tick of the clock by 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively, unless man becomes more realistic and preoccupied about this impending doom. The tick-tock of the clock will continually grow louder and more menacing each decade. Where will it all end?" However, some observers have suggested that by the 1990s Borlaug had changed his position on population control. They point to a quote from the year 2000 in which he stated: "I now say that the world has the technology—either available or well advanced in the research pipeline—to feed on a sustainable basis a population of 10 billion people. The more pertinent question today is whether farmers and ranchers will be permitted to use this new technology? While the affluent nations can certainly afford to adopt ultra low-risk positions, and pay more for food produced by the so-called 'organic' methods, the one billion chronically undernourished people of the low income, food-deficit nations cannot."Conko, Greg

The Man Who Fed the World

Openmarket.org. September 13, 2009. However, Borlaug remained on the advisory board of Population Media Center, an organization working to stabilize world population, until his death.

In 1968, Borlaug received what he considered an especially satisfying tribute when the people of

In 1968, Borlaug received what he considered an especially satisfying tribute when the people of

Norsk Høstfest

Borlaug was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1987, Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1987. In 2012, a new elementary school in the Iowa City, IA school district opened, called "Norman Borlaug Elementary". On August 19, 2013, his statue was unveiled inside the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, ICAR's NASC Complex at New Delhi,

(BISA)

in 2011. In 2006, the Texas A&M University System created the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture to be a premier institution for agricultural development and to continue the legacy of Dr. Borlaug. The stained-glass ''World Peace Window'' at St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral (Minneapolis, Minnesota), St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, depicts "peace makers" of the 20th century, including Norman Borlaug. Borlaug was also prominently mentioned in an episode ("In This White House") of the TV show ''The West Wing (TV series), The West Wing''. The president of a fictional African country describes the kind of "miracle" needed to save his country from the ravages of AIDS by referencing an American scientist who was able to save the world from hunger through the development of a new type of wheat. The U.S. president replies by providing Borlaug's name. Borlaug was also featured in an episode of ''Penn & Teller: Bullshit!'', where he was referred to as the "Greatest Human Being That Ever Lived". In that episode, Penn & Teller play a card game where each card depicts a great person in history. Each player picks a few cards at random, and bets on whether one thinks one's card shows a greater person than the other players' cards based on a characterization such as humanitarianism or scientific achievement. Penn gets Norman Borlaug, and proceeds to bet all his chips, his house, his rings, his watch, and essentially everything he's ever owned. He wins because, as he says, "Norman is the greatest human being, and you've probably never heard of him." In the episode—the topic of which was genetically altered food—he is credited with saving the lives of over a billion people. In August 2006, Dr. Leon Hesser published ''The Man Who Fed the World: Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Norman Borlaug and His Battle to End World Hunger'', an account of Borlaug's life and work. On August 4, the book received the 2006 Print of Peace award, as part of International Read For Peace Week. Borlaug is also the subject of the documentary film ''The Man Who Tried to Feed the World'' which first aired on ''American Experience'' on April 21, 2020.

On September 27, 2006, the United States Senate by unanimous consent passed the Congressional Tribute to Dr. Norman E. Borlaug Act of 2006. The act authorizes that Borlaug be awarded America's highest civilian award, the

In August 2006, Dr. Leon Hesser published ''The Man Who Fed the World: Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Norman Borlaug and His Battle to End World Hunger'', an account of Borlaug's life and work. On August 4, the book received the 2006 Print of Peace award, as part of International Read For Peace Week. Borlaug is also the subject of the documentary film ''The Man Who Tried to Feed the World'' which first aired on ''American Experience'' on April 21, 2020.

On September 27, 2006, the United States Senate by unanimous consent passed the Congressional Tribute to Dr. Norman E. Borlaug Act of 2006. The act authorizes that Borlaug be awarded America's highest civilian award, the List of Fellows of Bangladesh Academy of Sciences

The Borlaug Dialogue (Norman E. Borlaug International Symposium) is named in his honour.

*

*

The Green Revolution, Peace, and Humanity

'. 1970. Nobel Lecture, Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. December 11, 1970. * ''Wheat in the Third World''. 1982. Authors: Haldore Hanson, Norman E. Borlaug, and R. Glenn Anderson. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. * ''Land use, food, energy and recreation''. 1983. Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. * ''Feeding a human population that increasingly crowds a fragile planet''. 1994. Mexico City. * ''Norman Borlaug on World Hunger''. 1997. Edited by Anwar Dil. San Diego/Islamabad/Lahore: Bookservice International. 499 pages. *

The Green Revolution Revisited and the Road Ahead

'. 2000. Anniversary Nobel Lecture, Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. September 8, 2000. *

Ending World Hunger. The Promise of Biotechnology and the Threat of Antiscience Zealotry

. 2000. ''Plant Physiology'', October 2000, Vol. 124, pp. 487–90.

*

Feeding a World of 10 Billion People: The TVA/IFDC Legacy

'. International Fertilizer Development Center, 2003. * ''Prospects for world agriculture in the twenty-first century''. 2004. Norman E. Borlaug, Christopher R. Dowswell. Published in: ''Sustainable agriculture and the international rice-wheat system''. * Foreword to ''The Frankenfood Myth: How Protest and Politics Threaten the Biotech Revolution''. 2004. Henry I. Miller, Gregory Conko. *

Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

, India, and Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former c ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

. Twelve hours into the freighter's voyage, war broke out between India and Pakistan over the Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

region. Borlaug received a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

from the Pakistani minister of agriculture, Malik Khuda Bakhsh Bucha

Malik Khuda Bakhsh Bucha was a former agriculture minister of Pakistan. He served in the cabinet of Ayub Khan

Ayub Khan is a compound masculine name; Ayub is the Arabic version of the name of the Biblical figure Job, while Khan or Khaan is take ...

: "I'm sorry to hear you are having trouble with my check, but I've got troubles, too. Bombs are falling on my front lawn. Be patient, the money is in the bank ..."

These delays prevented Borlaug's group from conducting the germination tests needed to determine seed quality and proper seeding levels. They started planting immediately and often worked in sight of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

flashes. A week later, Borlaug discovered that his seeds were germinating at less than half the normal rate. It later turned out that the seeds had been damaged in a Mexican warehouse by over-fumigation with a pesticide. He immediately ordered all locations to double their seeding rates.

The initial yields of Borlaug's crops were higher than any ever harvested in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

. The countries subsequently committed to importing large quantities of both the Lerma Rojo 64 and Sonora 64 varieties. In 1966, India imported 18,000 tons—the largest purchase and import of any seed in the world at that time. In 1967, Pakistan imported 42,000 tons, and Turkey 21,000 tons. Pakistan's import, planted on 1.5 million acres (6,100 km2), produced enough wheat to seed the entire nation's wheatland the following year. By 1968, when Ehrlich's book was released, William Gaud of the United States Agency for International Development

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 b ...

was calling Borlaug's work a "Green Revolution". High yields led to a shortage of various utilities—labor to harvest the crops, bullock carts to haul it to the threshing floor, jute

Jute is a long, soft, shiny bast fiber that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced from flowering plants in the genus ''Corchorus'', which is in the mallow family Malvaceae. The primary source of the fiber is '' Corchorus ol ...

bags, trucks, rail cars, and grain storage facilities. Some local governments were forced to close school buildings temporarily to use them for grain storage.

tons

Tons can refer to:

* Tons River, a major river in India

* Tamsa River, locally called Tons in its lower parts (Allahabad district, Uttar pradesh, India).

* the plural of ton, a unit of mass, force, volume, energy or power

:* short ton, 2,000 poun ...

in 1965 to 7.3 million tons in 1970; Pakistan was self-sufficient in wheat production by 1968. Yields were over 21 million tons by 2000. In India, yields increased from 12.3 million tons in 1965 to 20.1 million tons in 1970. By 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. By 2000, India was harvesting a record 76.4 million tons (2.81 billion bushel

A bushel (abbreviation: bsh. or bu.) is an imperial and US customary unit of volume based upon an earlier measure of dry capacity. The old bushel is equal to 2 kennings (obsolete), 4 pecks, or 8 dry gallons, and was used mostly for agric ...

s) of wheat. Since the 1960s, food production in both nations has increased faster than the rate of population growth. India's use of high-yield farming has prevented an estimated 100 million acres (400,000 km2) of virgin land from being converted into farmland—an area about the size of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, or 13.6% of the total area of India.Easterbrook, G. 1997''Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity''

The Atlantic Monthly. The use of these wheat varieties has also had a substantial effect on production in six

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

n countries, six countries in the Near and Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and several others in Africa.

Borlaug's work with wheat contributed to the development of high-yield semi-dwarf ''indica'' and ''japonica'' rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and '' Porteresia'', both wild and domesticat ...

cultivars at the International Rice Research Institute and China's Hunan Rice Research Institute. Borlaug's colleagues at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research also developed and introduced a high-yield variety of rice throughout most of Asia. Land devoted to the semi-dwarf wheat and rice varieties in Asia expanded from 200 acres (0.8 km2) in 1965 to over 40 million acres (160,000 km2) in 1970. In 1970, this land accounted for over 10% of the more productive cereal land in Asia.

Nobel Peace Prize

For his contributions to the world food supply, Borlaug was awarded theNobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

in 1970. Norwegian officials notified his wife in Mexico City at 4:00 am, but Borlaug had already left for the test fields in the Toluca

Toluca , officially Toluca de Lerdo , is the state capital of the State of Mexico as well as the seat of the Municipality of Toluca. With a population of 910,608 as of the 2020 census, Toluca is the fifth most populous city in Mexico. The city ...

valley, about 40 miles (65 km) west of Mexico City. A chauffeur took her to the fields to inform her husband. According to his daughter, Jeanie Laube, "My mom said, 'You won the Nobel Peace Prize,' and he said, 'No, I haven't', ... It took some convincing ... He thought the whole thing was a hoax". He was awarded the prize on December 10.

In his Nobel Lecture the following day, he speculated on his award: "When the Nobel Peace Prize Committee designated me the recipient of the 1970 award for my contribution to the 'green revolution', they were in effect, I believe, selecting an individual to symbolize the vital role of agriculture and food production in a world that is hungry, both for bread and for peace".Borlaug, N. E. 1972Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1970

From ''Nobel Lectures, Peace 1951–1970'', Frederick W. Haberman Ed., Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam His speech repeatedly presented improvements in food production within a sober understanding of the context of

population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction usi ...

. "The green revolution has won a temporary success in man's war against hunger and deprivation; it has given man a breathing space. If fully implemented, the revolution can provide sufficient food for sustenance during the next three decades. But the frightening power of human reproduction must also be curbed; otherwise the success of the green revolution will be ephemeral only.

"Most people still fail to comprehend the magnitude and menace of the "Population Monster"...Since man is potentially a rational being, however, I am confident that within the next two decades he will recognize the self-destructive course he steers along the road of irresponsible population growth..."

Borlaug hypothesis

Borlaug continually advocated increasing crop yields as a means to curb deforestation. The large role he played in both increasing crop yields and promoting this view has led to this methodology being called by agricultural economists the "Borlaug hypothesis", namely that ''increasing the productivity of agriculture on the best farmland can help control deforestation by reducing the demand for new farmland''. According to this view, assuming that global food demand is on the rise, restricting crop usage to traditional low-yield methods would also require at least one of the following: the world population to decrease, either voluntarily or as a result of mass starvations; or the conversion of forest land into crop land. It is thus argued that high-yield techniques are ultimately savingecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

s from destruction. On a global scale, this view holds strictly true ''ceteris paribus

' (also spelled '; () is a Latin phrase, meaning "other things equal"; some other English translations of the phrase are "all other things being equal", "other things held constant", "all else unchanged", and "all else being equal". A statement ...

'', if deforestation only occurs to increase land for agriculture. But other land uses exist, such as urban areas, pasture, or fallow, so further research is necessary to ascertain what land has been converted for what purposes, to determine how true this view remains.