Nimrod (ship) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Nimrod'' was a wooden-hulled, three-masted

On 29 January 1908 ''Nimrod'' reached

On 29 January 1908 ''Nimrod'' reached  ''Nimrod'' then anchored off the

''Nimrod'' then anchored off the

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships ...

with auxiliary steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

that was built in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1867 as a whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

. She was the ship with which Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

made his ''Nimrod'' Expedition to Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

in 1908–09. After the expedition she returned to commercial service, and in 1919 she was wrecked in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

with the loss of ten members of her crew.

Building and registration

Alexander Stephen and Sons

Alexander Stephen and Sons Limited, often referred to simply as Alex Stephens or just Stephens, was a Scottish shipbuilding company based in Linthouse, Glasgow, on the River Clyde and, initially, on the east coast of Scotland.

History

The co ...

built ''Nimrod'' in Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

. Her launch date is not recorded, but she was completed in January 1867. Her registered length was , her beam was and her depth was . Her tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically r ...

s were and . She was rigged as a schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

. She had a single screw

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to ...

, driven by a 50 hp steam engine built by Gourlay Brothers

Gourlay Brothers was a marine engineering and shipbuilding company based in Dundee, Scotland. It existed between 1846 and 1908.

Company history

The company had its origins in the Dundee Foundry, founded in 1791. By 1820 the foundry was manufact ...

of Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

.

Her principal owner was Thomas B Job, who registered her at Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

. Her United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

official number

Official numbers are ship identifier numbers assigned to merchant ships by their country of registration. Each country developed its own official numbering system, some on a national and some on a port-by-port basis, and the formats have sometimes ...

was 55047. They used her for whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

and seal hunting

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. Seal hunting is currently practiced in ten countries: United States (above the Arctic Circle in Alaska), Canada, Namibia, Denmark (in self-governing Greenland only), Ice ...

.

By 1874 ''Nimrod'' was rigged as a barquentine

A barquentine or schooner barque (alternatively "barkentine" or "schooner bark") is a sailing vessel with three or more masts; with a square rigged foremast and fore-and-aft rigged main, mizzen and any other masts.

Modern barquentine sailing ...

. By 1888 her owners were listed as Job Brothers. By 1889 she had the code letters

Code letters or ship's call sign (or callsign) Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853"> SHIPSPOTTING.COM >> Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853/ref> were a method of identifying ships before the introduction of modern navigation aids and today also. Later, with the i ...

KWVT, and in that year Job Brothers re-registered her in St John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

. By 1891 her original engine had been replaced by a two-cylinder compound engine

A compound engine is an engine that has more than one stage for recovering energy from the same working fluid, with the exhaust from the first stage passing through the second stage, and in some cases then on to another subsequent stage or even st ...

built by Westray, Copeland & Co of Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town in Cumbria, England. Historically in Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. In 2023 t ...

. It was rated at 60 hp and gave her a speed of only .

''Nimrod'' expedition

In 1907 the shipbuilder William Beardmore bought ''Nimrod'' and re-registered her inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

as a yacht to serve as Shackleton's expedition ship. The purchase price was £5,000. She was in poor condition, needing caulk

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on ...

ing and renewal of her masts. In June 1907 she reached London, where she was overhauled.

King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second chil ...

and Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 to 6 May 1910 as the wife of ...

visited the ship, and on 11 August she left for Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, captained by Rupert England. She sailed via Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, and on 1 January 1908 she left New Zealand for the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-smal ...

. To conserve coal in ''Nimrod''s limited bunkers

A bunker is a defensive military fortification designed to protect people and valued materials from falling bombs, artillery, or other attacks. Bunkers are almost always underground, in contrast to blockhouses which are mostly above ground. T ...

, the Union Steam Ship Company cargo

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including tra ...

steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamship ...

''Koonya'' towed her as far as the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

, a distance of about . The Union Company Chairman Sir James Mills and the New Zealand Government

, background_color = #012169

, image = New Zealand Government wordmark.svg

, image_size=250px

, date_established =

, country = New Zealand

, leader_title = Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

, appointed = Governor-General

, main_organ =

...

each paid half the cost of the tow. From 14 January ''Nimrod'' continued under her own power.

On 29 January 1908 ''Nimrod'' reached

On 29 January 1908 ''Nimrod'' reached McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica. It is the southernmost navigable body of water in the world, and is about from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841, and named it after Lt. Archibald McMurdo ...

on 3 February she reached Cape Royds

Cape Royds is a dark rock cape forming the western extremity of Ross Island, facing on McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. It was discovered by the Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) and named for Lieutenant Charles Royds, Royal Navy, who acted as meteor ...

, where she landed Shackleton's equipment and expedition team. Shackleton became dissatisfied with Captain England, who often moved ''Nimrod'' away from shore when he feared the sea ice was unsafe. On 22 February she finished unloading and left for New Zealand, leaving Shackleton's party ashore to make their expedition.

Shackleton had Captain England replaced by Frederick Pryce Evans, who had captained ''Koonya'' when she towed ''Nimrod'' south in January 1908. In January 1909 Evans brought ''Nimrod'' back to Antarctica to rendezvous with the returning expedition team, which Shackleton had split into parties, each with its own objective. The "Northern Party" had explored Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

, and on 2 February 1909 reached its arrranged rendezvous point to meet the ship, but heavy drifting snow prevented ''Nimrod''s lookouts from seeing the Northern Party's camp. She continued to the Ferrar Glacier, where she picked up a three-man party who had been doing geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

work. She then returned, and two days later succeeded in finding and re-embarking the Northern Party.

''Nimrod'' then anchored off the

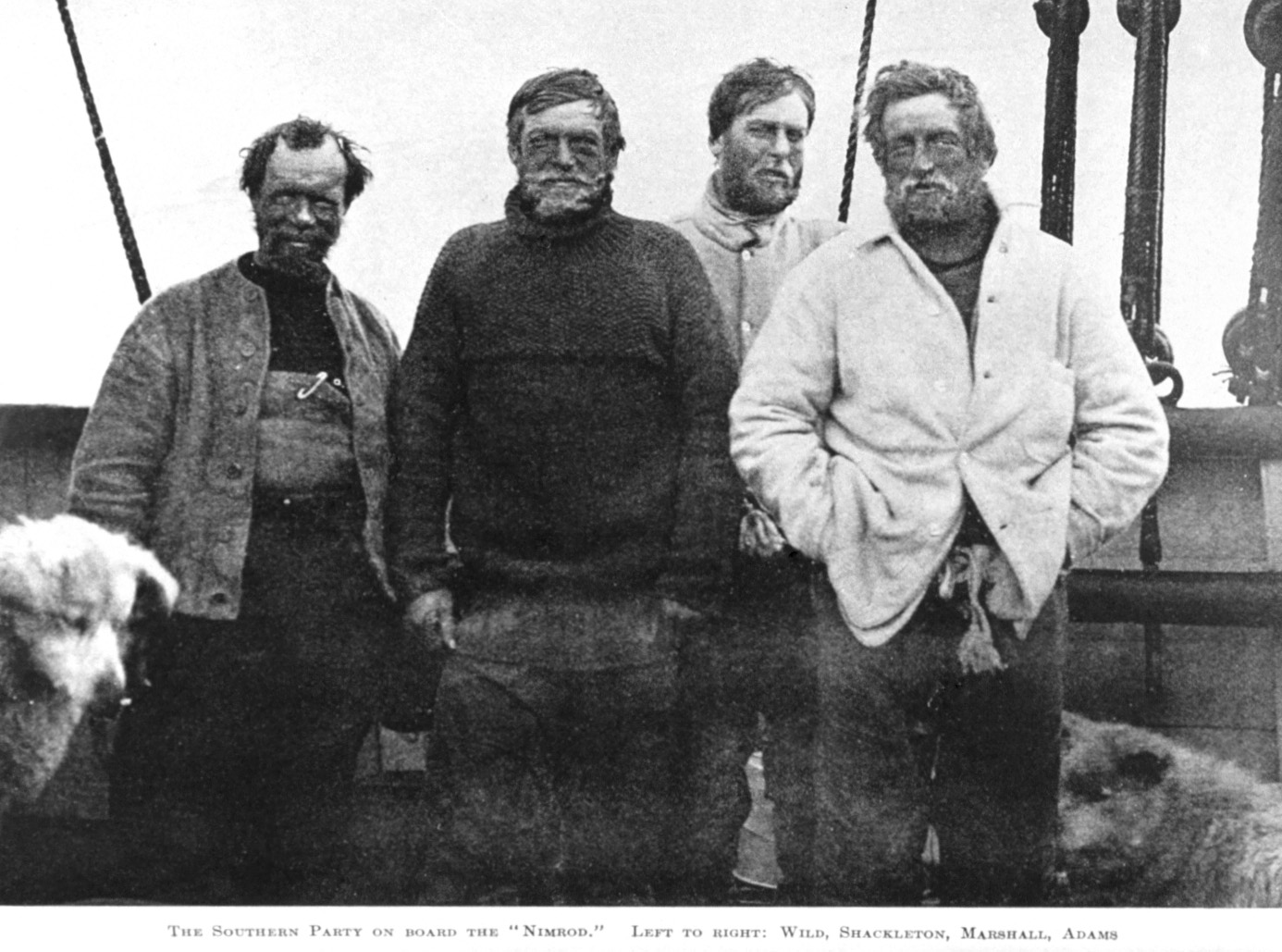

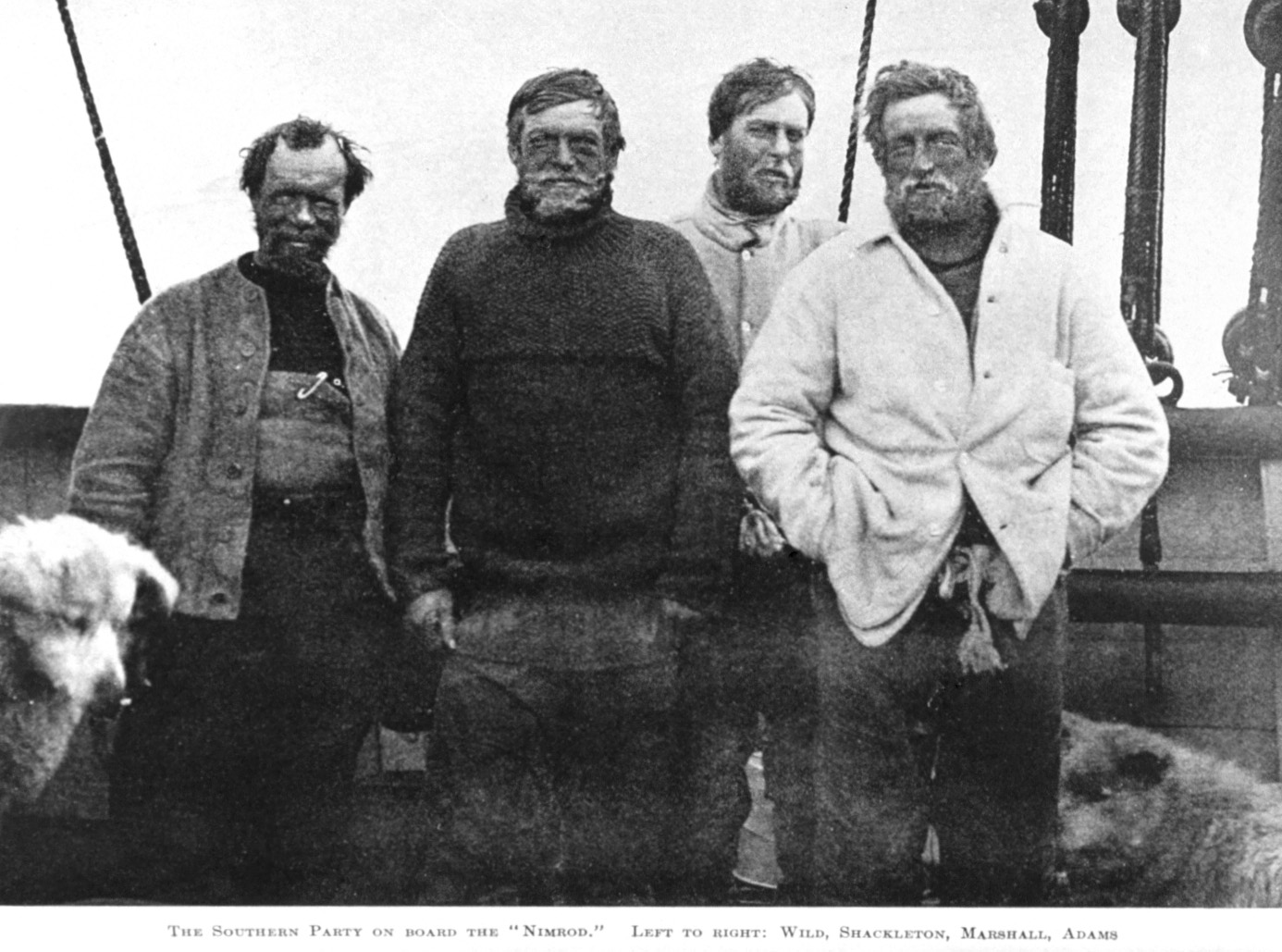

''Nimrod'' then anchored off the Erebus Ice Tongue

The Erebus Ice Tongue (more often called "Erebus Glacier Tongue") is a mountain outlet glacier and the seaward extension of Erebus Glacier from Ross Island. It projects into McMurdo Sound from the Ross Island coastline near Cape Evans, Antarcti ...

, and between 28 February and 4 March re-embarked Shackleton's "Southern Party", who had made the first successful ascent of Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

and had unsuccessfully tried to reach the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

. She had now re-embarked all of Shackleton's team and left Antarctica, reaching New Zealand on 23 March 1909. Shackleton's team named some features of Antarctica's geography after the ship, including the Nimrod Glacier

The Nimrod Glacier is a major glacier about 135 km (85 mi) long, flowing from the polar plateau in a northerly direction through the Transantarctic Mountains between the Geologists and Miller Ranges, then northeasterly between the ...

.

Later career and loss

By 1911 Shackleton owned ''Nimrod''. In 1913 her owner was a Roland V Webster. By 1917 her owner was The SS Nimrod Ltd, hermanager

Management (or managing) is the administration of an organization, whether it is a business, a nonprofit organization, or a government body. It is the art and science of managing resources of the business.

Management includes the activitie ...

was an Emile Dickers, and her code letters were JNFD.

In January 1919 ''Nimrod'', commanded by a Captain Duncan, left Blyth, Northumberland

Blyth () is a town and civil parish in southeast Northumberland, England. It lies on the coast, to the south of the River Blyth and is approximately northeast of Newcastle upon Tyne. It has a population of about 37,000, as of 2011.

The port o ...

with a cargo of coal for Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. On the night of 29–30 January she ran aground on the Barber Sands off Caister-on-Sea

Caister-on-Sea, also known colloquially as Caister, is a large village and seaside resort in Norfolk, England. It is close to the large town of Great Yarmouth. At the 2001 census it had a population of 8,756 and 3,970 households, the populati ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

. Her engine room

On a ship, the engine room (ER) is the compartment where the machinery for marine propulsion is located. To increase a vessel's safety and chances of surviving damage, the machinery necessary for the ship's operation may be segregated into var ...

flooded, killing her chief engineer

A chief engineer, commonly referred to as "ChEng" or "Chief", is the most senior engine officer of an engine department on a ship, typically a merchant ship, and holds overall leadership and the responsibility of that department..Chief engineer ...

. Her remaining 11 crew sheltered under her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually someth ...

. They fired distress flares, which were seen ashore. The Caister

Caister-on-Sea, also known colloquially as Caister, is a large village and seaside resort in Norfolk, England. It is close to the large town of Great Yarmouth. At the 2001 census it had a population of 8,756 and 3,970 households, the populati ...

lifeboat tried to reach her, but was unsuccessful. ''Nimrod''s crew launched her lifeboat, but the heavy sea capsized it. After six hours the boat was driven ashore, with two survivors clinging to it.

The bodies of seven of her crew were washed ashore. Captain Duncan's body was found north of Caister. Five bodies were found between Gorleston-on-Sea and Hopton-on-Sea

Hopton-on-Sea is a village, civil parish and seaside resort on the coast of East Anglia in the county of Norfolk. The village is south of Great Yarmouth, north-west of Lowestoft and near the UK's most easterly point, Lowestoft Ness.

The villa ...

, and one was found at California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

.

See also

List of Antarctic exploration ships from the Heroic Age, 1897–1922

This list includes all the main Antarctic exploration ships that were employed in the seventeen expeditions that took place in the era between 1897 and 1922, known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. A subsidiary list gives details of sup ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{1919 shipwrecks 1867 ships Auxiliary steamers Barquentines Ernest Shackleton Exploration ships of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in 1919 Merchant ships of the United Kingdom Schooners Ships built in Dundee Shipwrecks in the North Sea Whaling ships World War I ships of the United Kingdom