Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition, also known as the  The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir

The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist work had begun by 1909, under the leadership of

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist work had begun by 1909, under the leadership of

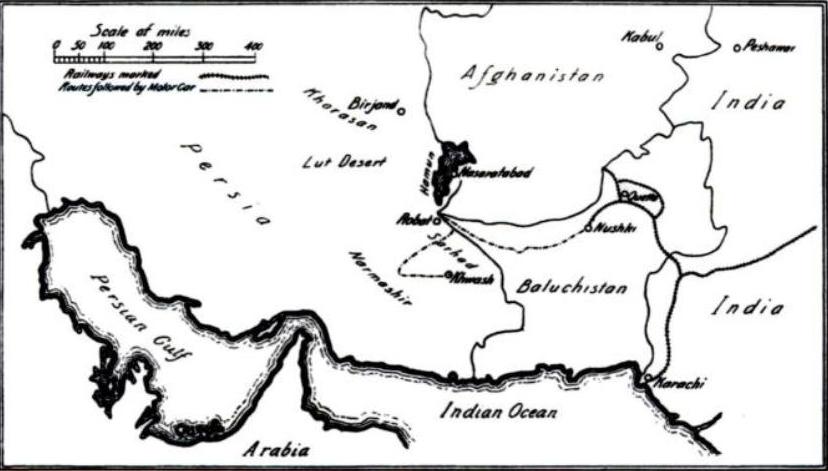

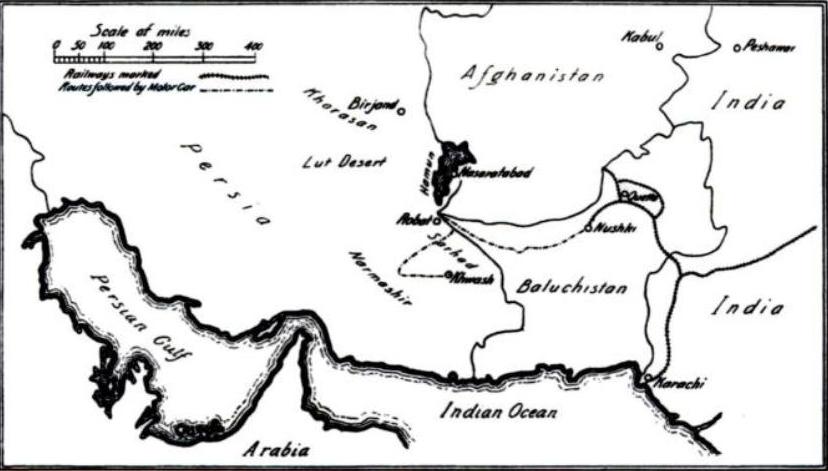

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to race against time. Ahead were British patrols of the

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to race against time. Ahead were British patrols of the  Although the town of Birjand was small, it had a Russian consulate. Niedermayer correctly guessed additional British forces were present. He therefore had to decide whether to bypass the town by the northern route, patrolled by Russians, or the southern route, where British patrols were present. He could not send any reconnaissance. His Persian escort's advice that the desert north of Birjand was notoriously harsh convinced him that this would be the route his enemies would least expect him to take. Sending a small decoy party south-east to spread the rumour that the main body would soon follow, Niedermayer headed for the north. His feints and disinformation were taking effect. The pursuing forces were spread thin, hunting for what they believed at times to be a large force. At other times they looked for a second, non-existent German force heading east from Kermanshah. The group now moved both day and night. From nomads, Niedermayer learnt the whereabouts of the British patrols. He lost men through exhaustion, defection, and desertion. On occasions, deserters would take the party's spare water and horses at gunpoint. Nonetheless, by the second week of August the forced march had brought the expedition close to the Birjand-

Although the town of Birjand was small, it had a Russian consulate. Niedermayer correctly guessed additional British forces were present. He therefore had to decide whether to bypass the town by the northern route, patrolled by Russians, or the southern route, where British patrols were present. He could not send any reconnaissance. His Persian escort's advice that the desert north of Birjand was notoriously harsh convinced him that this would be the route his enemies would least expect him to take. Sending a small decoy party south-east to spread the rumour that the main body would soon follow, Niedermayer headed for the north. His feints and disinformation were taking effect. The pursuing forces were spread thin, hunting for what they believed at times to be a large force. At other times they looked for a second, non-existent German force heading east from Kermanshah. The group now moved both day and night. From nomads, Niedermayer learnt the whereabouts of the British patrols. He lost men through exhaustion, defection, and desertion. On occasions, deserters would take the party's spare water and horses at gunpoint. Nonetheless, by the second week of August the forced march had brought the expedition close to the Birjand-

On 26 October 1915 the Emir finally granted an audience at his palace at

On 26 October 1915 the Emir finally granted an audience at his palace at

While the Emir vacillated, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and the Emir's younger son, Amanullah Khan. Nasrullah Khan had been present at the first meeting at Paghman. In secret meetings with the "Amanullah party" at his residence, he encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan gave the group reasons to feel confident, even as rumours of these meetings reached the Emir. Messages from von Hentig to Prince Henry, intercepted by British and Russian intelligence, were subsequently passed on to Emir Habibullah. These suggested that to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organise "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if necessary. Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. All of Afghanistan's immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah's father had died of unnatural causes. The fact that his immediate relatives were pro-German, while he was allied with Britain, gave him justifiable grounds to fear for his safety and his kingdom. Von Hentig described one audience with Habibullah where von Hentig set off his pocket alarm clock. The action, designed to impress Habibullah, instead frightened him; he may have believed it was a bomb about to go off. Despite von Hentig's reassurances and explanations, the meeting was a short one.

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central war effort with what has been described as "masterly inactivity". He waited for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India—if and when Turco-German troops were able to offer support. Hints that the mission would leave if nothing could be achieved were placated with flattery and invitations to stay on. Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty which was put to good use on a successful hearts and minds campaign, with expedition members spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct a hospital. Meanwhile, Kasim Bey acquainted himself with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad. Habibullah tolerated the increasingly anti-British and pro-Central tone being taken by his newspaper, ''Siraj al Akhbar'', whose editor—his father-in-law

While the Emir vacillated, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and the Emir's younger son, Amanullah Khan. Nasrullah Khan had been present at the first meeting at Paghman. In secret meetings with the "Amanullah party" at his residence, he encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan gave the group reasons to feel confident, even as rumours of these meetings reached the Emir. Messages from von Hentig to Prince Henry, intercepted by British and Russian intelligence, were subsequently passed on to Emir Habibullah. These suggested that to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organise "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if necessary. Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. All of Afghanistan's immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah's father had died of unnatural causes. The fact that his immediate relatives were pro-German, while he was allied with Britain, gave him justifiable grounds to fear for his safety and his kingdom. Von Hentig described one audience with Habibullah where von Hentig set off his pocket alarm clock. The action, designed to impress Habibullah, instead frightened him; he may have believed it was a bomb about to go off. Despite von Hentig's reassurances and explanations, the meeting was a short one.

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central war effort with what has been described as "masterly inactivity". He waited for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India—if and when Turco-German troops were able to offer support. Hints that the mission would leave if nothing could be achieved were placated with flattery and invitations to stay on. Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty which was put to good use on a successful hearts and minds campaign, with expedition members spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct a hospital. Meanwhile, Kasim Bey acquainted himself with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad. Habibullah tolerated the increasingly anti-British and pro-Central tone being taken by his newspaper, ''Siraj al Akhbar'', whose editor—his father-in-law

Historians have pointed out that in its political objectives, the expedition was three years premature. However, it planted the seeds of sovereignty and reform in Afghanistan, and its main themes of encouraging Afghan independence and breaking away from British influence were gaining ground in Afghanistan by 1919. Habibullah's steadfast neutrality alienated a substantial proportion of his family members and council advisors and fed discontent among his subjects. His communication to the Viceroy in early February 1919 demanding complete sovereignty and independence regarding foreign policy was rebuffed. Habibullah was assassinated while on a hunting trip two weeks later. The Afghan crown passed first to Nasrullah Khan before Habibullah's younger son, Amanullah Khan, assumed power. Both had been staunch supporters of the expedition. The immediate effect of this upheaval was the precipitation of the

Historians have pointed out that in its political objectives, the expedition was three years premature. However, it planted the seeds of sovereignty and reform in Afghanistan, and its main themes of encouraging Afghan independence and breaking away from British influence were gaining ground in Afghanistan by 1919. Habibullah's steadfast neutrality alienated a substantial proportion of his family members and council advisors and fed discontent among his subjects. His communication to the Viceroy in early February 1919 demanding complete sovereignty and independence regarding foreign policy was rebuffed. Habibullah was assassinated while on a hunting trip two weeks later. The Afghan crown passed first to Nasrullah Khan before Habibullah's younger son, Amanullah Khan, assumed power. Both had been staunch supporters of the expedition. The immediate effect of this upheaval was the precipitation of the

As part of their anti-British policies, the Soviet Union planned to foment political upheaval in British India. In 1919, the Soviet government sent a diplomatic mission headed by a Russian orientalist, N.Z. Bravin. Among other works, this expedition established links with the Austrian and German remnants of the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition at Herat and liaised with Indian revolutionaries in Kabul. Bravin proposed to Amanullah a military alliance against British India and a military campaign, with Soviet Turkestan bearing the costs. These negotiations failed to reach a concrete conclusion before the Soviet advances were detected by British Indian intelligence.

Other options were explored, including the Kalmyk Project, a Soviet plan to launch a surprise attack on the north-west frontier of India via

As part of their anti-British policies, the Soviet Union planned to foment political upheaval in British India. In 1919, the Soviet government sent a diplomatic mission headed by a Russian orientalist, N.Z. Bravin. Among other works, this expedition established links with the Austrian and German remnants of the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition at Herat and liaised with Indian revolutionaries in Kabul. Bravin proposed to Amanullah a military alliance against British India and a military campaign, with Soviet Turkestan bearing the costs. These negotiations failed to reach a concrete conclusion before the Soviet advances were detected by British Indian intelligence.

Other options were explored, including the Kalmyk Project, a Soviet plan to launch a surprise attack on the north-west frontier of India via

Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

Mission, was a diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase usually den ...

to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

sent by the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

in 1915–1916. The purpose was to encourage Afghanistan to declare full independence from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, enter World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on the side of the Central Powers, and attack British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. The expedition was part of the Hindu–German Conspiracy

The Indo–German Conspiracy (Note on the name) was a series of attempts between 1914 and 1917 by Indian nationalist groups to create a Pan-Indian rebellion against the British Empire during World War I. This rebellion was formulated betwee ...

, a series of Indo-German efforts to provoke a nationalist revolution in India. Nominally headed by the exiled Indian prince

The Indian Prince is a motorcycle manufactured by the Hendee Manufacturing Company from 1925 to 1928. An entry-level single-cylinder motorcycle, the Prince was restyled after its first year and discontinued after four years.

The frame and forks ...

Raja Mahendra Pratap

Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh (1 December 1886 – 29 April 1979) was an Indian freedom fighter, journalist, writer, revolutionary, President in the Provisional Government of India, which served as the Indian Government in exile during World War ...

, the expedition was a joint operation of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

and was led by the German Army officers Oskar Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig

Werner Otto von Hentig (22 May 1886, Berlin, Germany – 8 August 1984, Lindesnes, Norway) was a German Army Officer, adventurer and diplomat from Berlin. When still only a 25 year old lieutenant he was commissioned by the Kaiser to lead an exp ...

. Other participants included members of an Indian nationalist organisation called the Berlin Committee, including Maulavi Barkatullah

Mohamed Barakatullah Bhopali, known with his honorific as Maulana Barkatullah (7 July 1854 – 20 September 1927), was an Indian revolutionary with sympathy for the Pan-Islamic movement. Barkatullah was born on 7 July 1854 at Itwra Mohall ...

and Chempakaraman Pillai

Chempakaraman Pillai, alias Venkidi, (15 September 1891 – 26 May 1934) was an Indian-born political activist and revolutionary. Born in Thiruvananthapuram, to Tamil Pillai parents, he left for Europe as a youth, where he spent the rest of hi ...

, while the Turks were represented by Kazim Bey, a close confidante of Enver Pasha.

Britain saw the expedition as a serious threat. Britain and its ally, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, unsuccessfully attempted to intercept it in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

during the summer of 1915. Britain waged a covert intelligence and diplomatic offensive, including personal interventions by the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

Lord Hardinge and King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, to maintain Afghan neutrality.

The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir

The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir Habibullah Khan

Habibullah Khan (Pashto/Dari: ; 3 June 1872 – 20 February 1919) was the Emir of Afghanistan from 1901 until his death in 1919. He was the eldest son of the Emir Abdur Rahman Khan, whom he succeeded by right of primogeniture in October 1901 ...

, to the German and Turkish war effort, but it influenced other major events. In Afghanistan, the expedition triggered reforms and drove political turmoil that culminated in the assassination of the Emir in 1919, which in turn precipitated the Third Anglo-Afghan War

The Third Anglo-Afghan War; fa, جنگ سوم افغان-انگلیس), also known as the Third Afghan War, the British-Afghan War of 1919, or in Afghanistan as the War of Independence, began on 6 May 1919 when the Emirate of Afghanistan inv ...

. It influenced the Kalmyk Project of nascent Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

to propagate socialist revolution in Asia, with one goal being the overthrow of the British Raj. Other consequences included the formation of the Rowlatt Committee

The Rowlatt Committee was a Sedition Committee appointed in 1917 by the British Indian Government with Sidney Rowlatt, an Anglo-Egyptian judge, as its president.

Background

The purpose of the Rowlatt Committee was to evaluate political terrorism ...

to investigate sedition in India as influenced by Germany and Bolshevism, and changes in the Raj's approach to the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

immediately after World War I.

Background

In August 1914, World War I began when alliance obligations arising from the war between Serbia andAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

brought Germany and Russia to war, while Germany's invasion of Belgium directly triggered Britain's entry. After a series of military events and political intrigues, Russia declared war on Turkey in November. Turkey then joined the Central Powers in fighting the Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. In response to the war with Russia and Britain, and further motivated by its alliance with Turkey, Germany accelerated its plans to weaken its enemies by targeting their colonial empires, including Russia in Turkestan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turk ...

and Britain in India, using political agitation.

Germany began by nurturing its pre-war links with Indian nationalists, who had for years used Germany, Turkey, Persia, the United States, and other countries as bases for anti-colonial work directed against Britain. As early as 1913, revolutionary publications in Germany began referring to the approaching war between Germany and Britain and the possibility of German support for Indian nationalists. During the early months of the war, German newspaper devoted considerable coverage to social problems in India and instances of British economic exploitation.

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was the chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I. According to bio ...

encouraged this activity. The effort was led by prominent archaeologist and historian Max von Oppenheim

Baron Max von Oppenheim (15 July 1860, in Cologne – 17 November 1946, in Landshut) was a German lawyer, diplomat, ancient historian, and archaeologist. He was a member of the Oppenheim banking dynasty. Abandoning his career in diplomacy, h ...

, who headed the new Intelligence Bureau for the East

The Intelligence Bureau for the East (german: Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient, links=no) was a German intelligence organisation established on the eve of World War I dedicated to promoting and sustaining subversive and nationalist agitations i ...

and formed the Berlin Committee, which was later renamed the Indian Independence Committee. The Berlin Committee offered money, arms, and military advisors according to plans made by the German Foreign Office and Indian revolutionaries-in-exile such as members of the Ghadar Party

The Ghadar Movement was an early 20th century, international political movement founded by expatriate Indians to overthrow British rule in India. The early movement was created by conspirators who lived and worked on the West Coast of the Unite ...

in North America. The planners hoped to trigger a nationalist rebellion using clandestine shipments of men and arms sent to India from elsewhere in Asia and from the United States.

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist work had begun by 1909, under the leadership of

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist work had begun by 1909, under the leadership of Sardar Ajit Singh

Sardar Ajit Singh (23 February 1881 — 15 August 1947) was a revolutionary, an Indian dissident, and a nationalist during the time of British rule in India. With compatriots, he organised agitation by Punjabi peasants against anti-farmer laws ...

and Sufi Amba Prasad. Reports from 1910 indicate that Germany was already contemplating efforts to threaten India through Turkey, Persia, and Afghanistan. Germany had built close diplomatic and economic relationships with Turkey and Persia from the late 19th century. Von Oppenheim had mapped Turkey and Persia while working as a secret agent. The Kaiser toured Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, Damascus, and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

in 1898 to bolster the Turkish relationship and to portray solidarity with Islam, a religion professed by millions of subjects of the British Empire in India and elsewhere. Referring to the Kaiser as Haji

Hajji ( ar, الحجّي; sometimes spelled Hadji, Haji, Alhaji, Al-Hadj, Al-Haj or El-Hajj) is an honorific title which is given to a Muslim who has successfully completed the Hajj to Mecca. It is also often used to refer to an elder, since it ...

Wilhelm, the Intelligence Bureau for the East spread propaganda throughout the region, fostering rumours that the Kaiser had converted to Islam following a secret trip to Mecca and portraying him as a saviour of Islam.

Led by Enver Pasha, a coup in Turkey in 1913 sidelined Sultan Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd ( ota, محمد خامس, Meḥmed-i ḫâmis; tr, V. Mehmed or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) reigned as the 35th and penultimate Ottoman Sultan (). He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I. He succeeded his half-brother ...

and concentrated power in the hands of a junta. Despite the secular nature of the new government, Turkey retained its traditional influence over the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

. Turkey ruled Hejaz until the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

of 1916 and controlled the Muslim holy city of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

throughout the war. The Sultan's title of Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

was recognised as legitimate by most Muslims, including those in Afghanistan and India.

Once at war, Turkey joined Germany in taking aim at the opposing Entente Powers and their extensive empires in the Muslim world. Enver Pasha had the Sultan proclaim jihad. His hope was to provoke and aid a vast Muslim revolution, particularly in India. Translations of the proclamation were sent to Berlin for propaganda purposes, for distribution to Muslim troops of the Entente Powers. However, while widely heard, the proclamation did not have the intended effect of mobilising global Muslim opinion on behalf of Turkey or the Central Powers.

Early in the war, the Emir of Afghanistan

This article lists the heads of state of Afghanistan since the foundation of the first modern Afghan state, the Hotak Empire, in 1709.

History

The Hotak Empire was formed after a successful uprising led by Mirwais Hotak and other Afghan trib ...

declared neutrality. The Emir feared the Sultan's call to jihad would have a destabilising influence on his subjects. Turkey's entry into the war aroused widespread nationalist and pan-Islamic sentiments in Afghanistan and Persia. The Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907 designated Afghanistan to the British sphere of influence. Britain nominally controlled Afghanistan's foreign policy and the Emir received a monetary subsidy from Britain. In reality, however, Britain had almost no effective control over Afghanistan. The British perceived Afghanistan to be the only state capable of invading India, which remained a serious threat.

First Afghan expedition

In the first week of August 1914, the German Foreign Office and members of the military suggested attempting to use the pan-Islamic movement to destabilise the British Empire and begin an Indian revolution. The argument was reinforced byGermanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of German culture, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German citizen. The love of the ''Ge ...

explorer Sven Hedin in Berlin two weeks later. General Staff memoranda in the last weeks of August confirmed the perceived feasibility of the plan, predicting that an invasion by Afghanistan could cause a revolution in India.

With the outbreak of war, revolutionary unrest increased in India. Some Hindu and Muslim leaders secretly left to seek the help of the Central Powers in fomenting revolution. The pan-Islamic movement in India, particularly the Darul Uloom Deoband, made plans for an insurrection in the North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followi ...

, with support from Afghanistan and the Central Powers. Mahmud al Hasan, the principal of the Deobandi school, left India to seek the help of Galib Pasha, the Turkish governor of Hijaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provi ...

, while another Deoband leader, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi

Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi (10 March 1872 – 21 August 1944) was a political activist of the Indian independence movement and one of its vigorous leaders. According to ''Dawn'', Karachi, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi struggled for the independence ...

, travelled to Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

to seek the support of the Emir of Afghanistan. They initially planned to raise an Islamic army headquartered at Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, with an Indian contingent at Kabul. Mahmud al Hasan was to command this army. While at Kabul, Maulana came to the conclusion that focusing on the Indian Freedom Movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged from Bengal. ...

would best serve the pan-Islamic cause. Ubaidullah proposed to the Afghan Emir that he declare war against Britain. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was also involved in the movement prior to his arrest in 1916.

Enver Pasha conceived an expedition to Afghanistan in 1914. He envisioned it as a pan-Islamic venture directed by Turkey, with some German participation. The German delegation to this expedition, chosen by Oppenheim and Zimmermann, included Oskar Niedermayer and Wilhelm Wassmuss

Wilhelm Wassmuss (1880 – November 29, 1931; German spelling: Waßmuß) was a German diplomat and spy and part of Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition, known as "Wassmuss of Persia". According to British versions of history, he "attempted to fome ...

. An escort of nearly a thousand Turkish troops and German advisers was to accompany the delegation through Persia into Afghanistan, where they hoped to rally local tribes to jihad.

In an ineffective ruse, the Germans attempted to reach Turkey by travelling overland through Austria-Hungary in the guise of a travelling circus, eventually reaching neutral Romania. Their equipment, arms, and mobile radios were confiscated when Romanian officials discovered the wireless aerials sticking out through the packaging of the "tent poles". Replacements could not be arranged for weeks; the delegation waited at Constantinople. To reinforce the Islamic identity of the expedition, it was suggested that the Germans wear Turkish army uniforms, but they refused. Differences between Turkish and German officers, including the reluctance of the Germans to accept Turkish control, further compromised the effort. Eventually, the expedition was aborted.

The attempted expedition had a significant consequence. Wassmuss left Constantinople to organise the tribes in south Persia to act against British interests. While evading British capture in Persia, Wassmuss inadvertently abandoned his codebook. Its recovery by Britain allowed the Allies to decipher German communications, including the Zimmermann Telegram in 1917. Niedermayer led the group following Wassmuss's departure.

Second expedition

In 1915, a second expedition was organised, mainly through the German Foreign Office and the Indian leadership of the Berlin Committee. Germany was now extensively involved in the Indian revolutionary conspiracy and provided it with arms and funds.Lala Har Dayal

Lala Har Dayal Mathur ( Punjabi: ਲਾਲਾ ਹਰਦਿਆਲ; 14 October 1884 – 4 March 1939) was an Indian nationalist revolutionary and freedom fighter. He was a polymath who turned down a career in the Indian Civil Service. His simp ...

, prominent among the Indian radicals liaising with Germany, was expected to lead the expedition. When he declined, the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap

Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh (1 December 1886 – 29 April 1979) was an Indian freedom fighter, journalist, writer, revolutionary, President in the Provisional Government of India, which served as the Indian Government in exile during World War ...

was named leader.

Composition

Mahendra Pratap was head of the Indian princely states ofMursan

Mursan is a town and a Nagar Panchayat in Hathras district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The primary spoken language is a dialect of Hindi, Braj Bhasha, which is closely related to Khariboli. In past, Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh was the ...

and Hathras. He had been involved with the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

in the 1900s, attending the Congress session of 1906. He toured the world in 1907 and 1911, and in 1912 contributed substantial funds to Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

's South African movement. Pratap left India for Geneva at the beginning of the war, where he was met by Virendranath Chattopadhyaya

Virendranath Chattopadhyaya ( bn, বীরেন্দ্রনাথ চট্টোপাধ্যায়), alias Chatto, (31 October 1880 – 2 September 1937, Moscow), also known by his pseudonym Chatto, was a prominent Indian revolutiona ...

of the Berlin Committee. Chattopadhyaya's efforts—along with a letter from the Kaiser—convinced Pratap to lend his support to the Indian nationalist cause, on the condition that the arrangements were made with the Kaiser himself. A private audience with the Kaiser was arranged, at which Pratap agreed to nominally head the expedition.

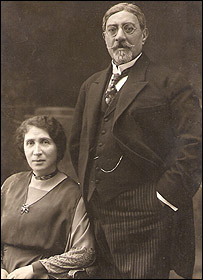

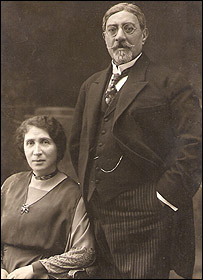

Prominent among the German members of the delegation were Niedermayer and von Hentig. Von Hentig was a Prussian military officer who had served as the military attaché to Beijing in 1910 and Constantinople in 1912. Fluent in Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, he was appointed secretary of the German legation to Tehran in 1913. Von Hentig was serving on the Eastern front as a lieutenant with the Prussian 3rd Cuirassiers when he was recalled to Berlin for the expedition.

Like von Hentig, Niedermayer had served in Constantinople before the war and spoke fluent Persian and other regional languages. A Bavarian artillery officer and a graduate from the University of Erlangen

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

, Niedermayer had travelled in Persia and India in the two years preceding the war. He returned to Persia to await further orders after the first Afghan expedition was aborted. Niedermayer was tasked with the military aspect of this new expedition as it proceeded through the dangerous Persian desert between British and Russian areas of influence. The delegation also included German officers Günter Voigt and Kurt Wagner.

Accompanying Pratap were other Indians from the Berlin Committee, notably Champakaraman Pillai

Chempakaraman Pillai, alias Venkidi, (15 September 1891 – 26 May 1934) was an Indian-born political activist and revolutionary. Born in Thiruvananthapuram, to Tamil Pillai parents, he left for Europe as a youth, where he spent the rest of hi ...

and the Islamic scholar and Indian nationalist Maulavi Barkatullah

Mohamed Barakatullah Bhopali, known with his honorific as Maulana Barkatullah (7 July 1854 – 20 September 1927), was an Indian revolutionary with sympathy for the Pan-Islamic movement. Barkatullah was born on 7 July 1854 at Itwra Mohall ...

. Barkatullah had long been associated with the Indian revolutionary movement, having worked with the India House

India House was a student residence that existed between 1905 and 1910 at Cromwell Avenue in Highgate, North London. With the patronage of lawyer Shyamji Krishna Varma, it was opened to promote nationalist views among Indian students in Britai ...

in London and New York from 1903. In 1909, he moved to Japan, where he continued his anti-British activities. Taking the post of Professor of Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

'' Tokyo University , abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

, he visited Constantinople in 1911. However, his Tokyo tenure was terminated under diplomatic pressure from Britain. He returned to the United States in 1914, later proceeding to Berlin, where he joined the efforts of the Berlin Committee. Barkatullah had as early as 1895 been acquainted with Nasrullah Khan, the brother of the Afghan Emir, '' Tokyo University , abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

Habibullah Khan

Habibullah Khan (Pashto/Dari: ; 3 June 1872 – 20 February 1919) was the Emir of Afghanistan from 1901 until his death in 1919. He was the eldest son of the Emir Abdur Rahman Khan, whom he succeeded by right of primogeniture in October 1901 ...

.

Pratap chose six Afghan Afridi

The Afrīdī ( ps, اپريدی ''Aprīdai'', plur. ''Aprīdī''; ur, آفریدی) are a Pashtun tribe present in Pakistan, with substantial numbers in Afghanistan. The Afridis are most dominant in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal ...

and Pathan

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically re ...

volunteers from the prisoner of war camp at Zossen

Zossen (; hsb, Sosny) is a German town in the district of Teltow-Fläming in Brandenburg, about south of Berlin, and next to the Bundesstraße 96, B96 highway. Zossen consists of several smaller municipalities, which were grouped together in 200 ...

. Before the mission left Berlin, two more Germans joined the group: Major Dr. Karl Becker, who was familiar with tropical diseases and spoke Persian, and Walter Röhr, a young merchant fluent in Turkish and Persian.

Organisation

The titular head of the expedition was Mahendra Pratap, while von Hentig was the Kaiser's representative. He was to accompany and introduce Mahendra Pratap and was responsible for the German diplomatic representations to the Emir. To fund the mission, 100,000pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

in gold was deposited in an account at the Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank AG (), sometimes referred to simply as Deutsche, is a German multinational investment bank and financial services company headquartered in Frankfurt, Germany, and dual-listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and the New York Sto ...

in Constantinople. The expedition was also provided with gold and other gifts for the Emir, including jewelled watches, gold fountain pens, ornamental rifles, binoculars, cameras, cinema projectors, and an alarm clock.

Supervision of the mission was assigned to the German Ambassador to Turkey, Hans von Wangenheim, but as he was ill, his functions were delegated to Prince zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Following Wangenheim's death in 1915, Count von Wolff-Metternich was designated his successor. He had little contact with the expedition.

Journey

To evade British and Russian intelligence, the group split up, beginning their journeys on different days and separately making their way to Constantinople. Accompanied by a German orderly and an Indian cook, Pratap and von Hentig began their journey in early spring 1915, travelling viaVienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

, and Adrianople to Constantinople. At Vienna, they were met briefly by the deposed Khedive of Egypt, Abbas Hilmi.

Persia and Isfahan

Reaching Constantinople on 17 April, the party waited at the Pera Palace Hotel for three weeks while further travel arrangements were made. During this time, Pratap and Hentig met with Enver Pasha and enjoyed an audience with the Sultan. On Enver Pasha's orders, a Turkish officer, Lieutenant Kasim Bey, was deputed to the expedition as the Turkish representative, bearing official letters addressed to the Afghan Emir and the Indian princely states. Two Afghans from the United States also joined the expedition. The group, now numbering approximately twenty people, left Constantinople in early May 1915. They crossed the Bosphorus to take the unfinishedBaghdad Railway

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

. The Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

were crossed on horseback, using—as von Hentig reflected—the same route taken by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, Paul the Apostle, and Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoll ...

. The group crossed the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers''). Originating in Turkey, the Eup ...

at high flood, finally reaching Baghdad towards the end of May.

As Baghdad raised the spectre of an extensive network of British spies, the group again split. Pratap and von Hentig's party left on 1 June 1915 to make their way towards the Persian border. Eight days later they were received by the Turkish military commander Rauf Orbay

Hüseyin Rauf Orbay (27 July 1881 – 16 July 1964) was an Ottoman-born Turkish naval officer, statesman and diplomat of Abkhazian origin.

Biography

Hüseyin Rauf was born in Constantinople in 1881 to an Abkhazian family. As an officer i ...

at the Persian town of Krynd. Leaving Krynd, the party reached Turkish-occupied Kermanshah

Kermanshah ( fa, کرمانشاه, Kermânšâh ), also known as Kermashan (; romanized: Kirmaşan), is the capital of Kermanshah Province, located from Tehran in the western part of Iran. According to the 2016 census, its population is 946,68 ...

on 14 June 1915. Some members were sick with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

and other tropical diseases. Leaving them under the care of Dr. Becker, von Hentig proceeded towards Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

to decide on the subsequent plans with Prince Heinrich Reuss and Niedermayer.

Persia at the time was divided into British and Russian spheres of influence, with a neutral zone in between. Germany exercised influence over the central parts of the country through their consulate in Isfahan. The local populace and the clergy, opposed to Russian and British semi-colonial designs on Persia, offered support to the mission. Niedermayer and von Hentig's groups reconnoitred Isfahan until the end of June. The Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, Lord Hardinge, was already receiving reports of pro-German sympathies among Persian and Afghan tribes. Details of the progress of the expedition were being keenly sought by British intelligence. By now, British and Russian columns close to the Afghan border, including the Seistan Force

The Seistan Force, originally called East Persia Cordon, was a force of British Indian Army troops set up to prevent infiltration by German and Ottoman agents from Persia (Iran) into Afghanistan during World War I. The force was established to pr ...

, were hunting for the expedition. If the expedition was to reach Afghanistan, it would have to outwit and outrun its pursuers over thousands of miles in the extreme heat and natural hazards of the Persian desert, while evading brigands and ambushes.

By early July, the sick at Kermanshah had recovered and rejoined the expedition. Camels and water bags were purchased, and the parties left Isfahan separately on 3 July 1915 for the journey through the desert, hoping to rendezvous at Tebbes, halfway to the Afghan border. Von Hentig's group travelled with twelve pack horses, twenty-four mules, and a camel caravan

A camel train or caravan is a series of camels carrying passengers and goods on a regular or semi-regular service between points. Despite rarely travelling faster than human walking speed, for centuries camels' ability to withstand harsh condi ...

. Throughout the march, efforts were made to throw off the British and Russian patrols. False dispatches spread disinformation on the group's numbers, destination, and intention. To avoid the extreme daytime heat, they travelled by night. Food was found or bought by Persian messengers sent ahead of the party. These scouts also helped identify hostile villages and helped find water. The group crossed the Persian desert in forty nights. Dysentery and delirium plagued the party. Some Persian guides attempted to defect, and camel drivers had to be constantly vigilant for robbers. On 23 July, the group reached Tebbes – the first Europeans after Sven Hedin. They were soon followed by Niedermayer's party, which now included explorer Wilhelm Paschen and six Austrian and Hungarian soldiers who had escaped from Russian prisoner of war camps in Turkestan. The arrival was marked by a grand welcome by the town's mayor. However, the welcome meant the party had been spotted.

East Persian Cordon

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to race against time. Ahead were British patrols of the

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to race against time. Ahead were British patrols of the East Persia Cordon

The Seistan Force, originally called East Persia Cordon, was a force of British Indian Army troops set up to prevent infiltration by German and Ottoman agents from Persia (Iran) into Afghanistan during World War I. The force was established to pro ...

(later known as the Seistan Force) and Russian patrols. By September, the German codebook lost by Wassmuss had been deciphered, which further compromised the situation. Niedermayer, now in charge, proved to be a brilliant tactician. He sent three feint patrols, one to north-east to draw away the Russian troops and one to the south-east to draw away the British, while a third patrol of thirty armed Persians, led by a German officer—Lieutenant Wagner—was sent ahead to scout the route. After leading the Russians astray, the first group was to remain in Persia to establish a secret desert base as a refuge for the main party. After luring away the British, the second group was to fall back to Kermanshah and link with a separate German force under Lieutenants Zugmayer and Griesinger. All three parties were ordered to spread misleading information about their movements to any nomads or villagers they met. Meanwhile, the main body headed through Chehar Deh for the region of Birjand, close to the Afghan frontier. The party covered forty miles before it reached the next village, where Niedermayer halted to await word from Wagner's patrol. The villagers were meanwhile barred from leaving. The report from Wagner was bad: His patrol had run into a Russian ambush and the desert refuge had been eliminated. The expedition proceeded towards Birjand using forced marches to keep a day ahead of the British and Russian patrols. Other problems still confronted Niedermayer, among them the opium addiction of his Persian camel drivers. Fearful of being spotted, he had to stop the Persians a number of times from lighting up their pipes. Men who fell behind were abandoned. Some of the Persian drivers attempted to defect. On one occasion, a driver was shot while he attempted to flee and betray the group.

Although the town of Birjand was small, it had a Russian consulate. Niedermayer correctly guessed additional British forces were present. He therefore had to decide whether to bypass the town by the northern route, patrolled by Russians, or the southern route, where British patrols were present. He could not send any reconnaissance. His Persian escort's advice that the desert north of Birjand was notoriously harsh convinced him that this would be the route his enemies would least expect him to take. Sending a small decoy party south-east to spread the rumour that the main body would soon follow, Niedermayer headed for the north. His feints and disinformation were taking effect. The pursuing forces were spread thin, hunting for what they believed at times to be a large force. At other times they looked for a second, non-existent German force heading east from Kermanshah. The group now moved both day and night. From nomads, Niedermayer learnt the whereabouts of the British patrols. He lost men through exhaustion, defection, and desertion. On occasions, deserters would take the party's spare water and horses at gunpoint. Nonetheless, by the second week of August the forced march had brought the expedition close to the Birjand-

Although the town of Birjand was small, it had a Russian consulate. Niedermayer correctly guessed additional British forces were present. He therefore had to decide whether to bypass the town by the northern route, patrolled by Russians, or the southern route, where British patrols were present. He could not send any reconnaissance. His Persian escort's advice that the desert north of Birjand was notoriously harsh convinced him that this would be the route his enemies would least expect him to take. Sending a small decoy party south-east to spread the rumour that the main body would soon follow, Niedermayer headed for the north. His feints and disinformation were taking effect. The pursuing forces were spread thin, hunting for what they believed at times to be a large force. At other times they looked for a second, non-existent German force heading east from Kermanshah. The group now moved both day and night. From nomads, Niedermayer learnt the whereabouts of the British patrols. He lost men through exhaustion, defection, and desertion. On occasions, deserters would take the party's spare water and horses at gunpoint. Nonetheless, by the second week of August the forced march had brought the expedition close to the Birjand-Meshed

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of Razavi Khorasan Province and has a po ...

road, eighty miles from Afghanistan. Here the Kaiser's bulkier and heavier gifts to the Emir, including the German wireless sets, were buried in the desert for later retrieval. Since all caravans entering Afghanistan must cross the road, Niedermayer assumed it was watched by British spies. An advance patrol reported seeing British columns. With scouts on the lookout, the expedition crossed under the cover of night. Only one obstacle, the so-called "Mountain Path", remained before they were clear of the Anglo-Russian cordon. This heavily patrolled path, thirty miles further east, was the site of Entente telegraph lines for maintaining communication with remote posts. However, even here, Niedermayer escaped. His group had covered 255 miles in seven days, through the barren Dasht-e Kavir

Dasht-e Kavir ( fa, دشت كوير, lit=Low Plains in classical Persian, from ''khwar'' (low), and ''dasht'' (plain, flatland)), also known as Kavir-e Namak () and the Great Salt Desert, is a large desert lying in the middle of the Iranian Plat ...

. On 19 August 1915 the expedition reached the Afghan frontier. Mahendra Pratap's memoirs describe the group as left with approximately fifty men, less than half the number who had set out from Isfahan seven weeks earlier. Dr. Becker's camel caravan was lost and he was later captured by Russians. Only 70 of the 170 horses and baggage animals survived.

Afghanistan

Crossing into Afghanistan, the group found fresh water in an irrigation channel by a deserted hamlet. Albeit teeming with leeches, the water saved the group from dying of thirst. Marching for another two days, they reached the vicinity ofHerat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Safē ...

, where they made contact with Afghan authorities. Unsure what reception awaited them, von Hentig sent Barkatullah, an Islamic scholar of some fame, to advise the governor that the expedition had arrived and was bearing the Kaiser's message and gifts for the Emir. The governor sent a grand welcome, with noblemen bearing cloths and gifts, a caravan of servants, and a column of hundred armed escorts. The expedition was invited into the city as guests of the Afghan government. With von Hentig in the lead in his Cuirassiers uniform, they entered Herat on 24 August, in a procession welcomed by Turkish troops. They were housed at the Emir's provincial palace. They were officially met by the governor a few days later when, according to British agents, von Hentig showed him the Turkish Sultan's proclamation of jihad and announced the Kaiser's promise to recognise Afghan sovereignty and provide German assistance. The Kaiser also promised to grant territory to Afghanistan as far north as Samarkand in Russian Turkestan and as far into India as Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

.

The Viceroy of India had already warned the Emir of approaching "German agents and hired assassins", and the Emir had promised he would arrest the expedition if it managed to reach Afghanistan. However, under a close watch, the expedition members were given the freedom of Herat. The governor promised to arrange for the 400-mile trip east to Kabul in another two weeks. Suits were tailored and horses given new saddles to make everything presentable for the meeting with the Emir. The southern route and the city of Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the c ...

were avoided, possibly because Afghan officials wished to prevent fomenting unrest in the Pathan region close to India. On 7 September, the group left Herat for Kabul with Afghan guides on a 24-day trip via the harsher northern route through Hazarajat

Hazaristan ( fa, هزارستان, Hazāristān), or Hazarajat ( fa, هزارهجات, Hazārajāt) is a mostly mountainous region in the central highlands of Afghanistan, among the Koh-i-Baba mountains in the western extremities of the ...

, over the barren mountains of central Afghanistan. En route the expedition was careful to spend enough money and gold to ensure popularity amongst the local people. Finally, on 2 October 1915, the expedition reached Kabul. It was received with a ''salaam'' from the local Turkish community and a Guard of honour from Afghan troops in Turkish uniform. Von Hentig later described receiving cheers and a grand welcome from the inhabitants of Kabul.

Afghan intrigues

At Kabul, the group was accommodated as state guests at the Emir's palace atBagh-e Babur

The Garden of Babur (locally called Bagh-e Babur; fa, باغ بابر, ''bāġ-e bābur'') is a historic park in Kabul, Afghanistan, and also has the tomb of the first Mughal emperor Babur. The garden is thought to have been developed around 152 ...

. Despite the comfort and the welcome, it was soon clear that they were all but confined. Armed guards were stationed around the palace, ostensibly for "the group's own danger from British secret agents", and armed guides escorted them on their journeys. For nearly three weeks, Emir Habibullah, reportedly in his summer palace at Paghman

Paghman (Persian/Pashto: پغمان) is a town in the hills near Afghanistan's capital of Kabul. It is the seat of the Paghman District (in the western part of Kabul Province) which has a population of about 120,000 (2002 official UNHCR est.), ma ...

, responded with only polite noncommittal replies to requests for an audience. An astute politician, he was in no hurry to receive his guests; he used the time to find out as much as he could about the expedition members and liaised with British authorities at New Delhi. It was only after Niedermayer and von Hentig threatened to launch a hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

that meetings began. In the meantime, von Hentig learnt as much as he could about his eccentric host. Emir Habibullah was, by all measures, the lord of Afghanistan. He considered it his divine right to rule and the land his property. He owned the only newspaper, the only drug store, and all the automobiles in the country (all Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

s).

The Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, was a man of religious convictions. Unlike the Emir, he fluently spoke Pashto

Pashto (,; , ) is an Eastern Iranian language in the Indo-European language family. It is known in historical Persian literature as Afghani ().

Spoken as a native language mostly by ethnic Pashtuns, it is one of the two official langua ...

(the local language), dressed in traditional Afghan robes, and interacted more closely with the border tribes. While the Emir favoured British India, Nasrullah Khan was more pro-German in his sympathies. Nasrullah's views were shared by his nephew, Amanullah Khan

Ghazi Amanullah Khan ( Pashto and Dari: ; 1 June 1892 – 25 April 1960) was the sovereign of Afghanistan from 1919, first as Emir and after 1926 as King, until his abdication in 1929. After the end of the Third Anglo-Afghan War in August 1 ...

, the youngest and most charismatic of the Emir's sons. The eldest son, Inayatullah Khan, was in charge of the Afghan army. The mission therefore expected more sympathy and consideration from Nasrullah and Amanullah than from the emir.

Meeting Emir Habibullah

On 26 October 1915 the Emir finally granted an audience at his palace at

On 26 October 1915 the Emir finally granted an audience at his palace at Paghman

Paghman (Persian/Pashto: پغمان) is a town in the hills near Afghanistan's capital of Kabul. It is the seat of the Paghman District (in the western part of Kabul Province) which has a population of about 120,000 (2002 official UNHCR est.), ma ...

, which provided privacy from British secret agents. The meeting, which lasted the entire day, began on an uncomfortable note, with Habibullah summing up his views on the expedition in a prolonged opening address:

He expressed surprise that a task as important as the expedition's was entrusted to such young men. Von Hentig had to convince the Emir that the mission did not consider themselves merchants, but instead brought word from the Kaiser, the Ottoman Sultan, and from India, wishing to recognise Afghanistan's complete independence and sovereignty. The Kaiser's typewritten letter, which he compared to the handsome greeting received from the Ottomans, failed to settle the Emir's suspicions; he doubted its authenticity. Von Hentig's explanation that the Kaiser had written the letter using the only instrument available at his field headquarters before the group's hurried departure may not have entirely convinced him. Passing along the Kaiser's invitation to join the war on the side of the Central Powers, von Hentig described the war situation as favourable and invited the Emir to declare independence. This was followed by a presentation from Kasim Bey explaining the Ottoman Sultan's declaration of jihad and Turkey's desire to avoid a fratricidal war between Islamic peoples. He passed along a message to Afghanistan similar to the Kaiser's. Barkatullah invited Habibullah to declare war against the British Empire and to come to the aid of India's Muslims. He proposed that the Emir should allow Turco-German forces to cross Afghanistan for a campaign towards the Indian frontier, a campaign which he hoped the Emir would join. Barkatullah and Mahendra Pratap, both eloquent speakers, pointed out the rich territorial gains the Emir stood to acquire by joining the Central Powers.

The Emir's reply was shrewd but frank. He noted Afghanistan's vulnerable strategic position between the two allied nations of Russia and Britain, and the difficulties of any possible Turco-German assistance to Afghanistan, especially given the presence of the Anglo-Russian East Persian Cordon. Further, he was financially vulnerable, dependent on British subsidies and institutions for his fortune and the financial welfare of his army and kingdom. The members of the mission had no immediate answers to his questions regarding strategic assistance, arms, and funds. Merely tasked to entreat the Emir to join a holy war, they did not have the authority to promise anything. Nonetheless, they expressed hopes of an alliance with Persia in the near future (a task Prince Henry of Reuss and Wilhelm Wassmuss worked on), which would help meet the Emir's needs. Although it reached no firm outcome, this first meeting has been noted by historians as being cordial, helping open communications with the Emir and allowing the mission to hope for success.

This conference was followed by an eight-hour meeting in October 1915 at Paghman and more audiences at Kabul. The message was the same as at the first audience. The meetings would typically begin with Habibullah describing his daily routine, followed by words from von Hentig on politics and history. Next the discussions veered towards Afghanistan's position on the propositions of allowing Central Powers troops the right of passage, breaking with Britain, and declaring independence. The expedition members expected a Persian move to the Central side, and held out on hopes that this would convince the Emir to join as well. Niedermayer argued that German victory was imminent; he outlined the compromised and isolated position Afghanistan would find herself in if she was still allied to Britain. At times the Emir met with the Indian and German delegates separately, promising to consider their propositions, but never committing himself. He sought concrete proof that the Turco-German assurances of military and financial assistance were feasible. In a letter to Prince Henry of Reuss in Tehran (a message that was intercepted and delivered to the Russians instead), von Hentig asked for Turkish troops. Walter Röhr later wrote to the prince that a thousand Turkish troops armed with machine guns—along with another German expedition headed by himself—should be able to draw Afghanistan into the war. Meanwhile, Niedermayer advised Habibullah on how to reform his army with mobile units and modern weaponry.

Meetings with Nasrullah

While the Emir vacillated, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and the Emir's younger son, Amanullah Khan. Nasrullah Khan had been present at the first meeting at Paghman. In secret meetings with the "Amanullah party" at his residence, he encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan gave the group reasons to feel confident, even as rumours of these meetings reached the Emir. Messages from von Hentig to Prince Henry, intercepted by British and Russian intelligence, were subsequently passed on to Emir Habibullah. These suggested that to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organise "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if necessary. Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. All of Afghanistan's immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah's father had died of unnatural causes. The fact that his immediate relatives were pro-German, while he was allied with Britain, gave him justifiable grounds to fear for his safety and his kingdom. Von Hentig described one audience with Habibullah where von Hentig set off his pocket alarm clock. The action, designed to impress Habibullah, instead frightened him; he may have believed it was a bomb about to go off. Despite von Hentig's reassurances and explanations, the meeting was a short one.

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central war effort with what has been described as "masterly inactivity". He waited for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India—if and when Turco-German troops were able to offer support. Hints that the mission would leave if nothing could be achieved were placated with flattery and invitations to stay on. Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty which was put to good use on a successful hearts and minds campaign, with expedition members spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct a hospital. Meanwhile, Kasim Bey acquainted himself with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad. Habibullah tolerated the increasingly anti-British and pro-Central tone being taken by his newspaper, ''Siraj al Akhbar'', whose editor—his father-in-law

While the Emir vacillated, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and the Emir's younger son, Amanullah Khan. Nasrullah Khan had been present at the first meeting at Paghman. In secret meetings with the "Amanullah party" at his residence, he encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan gave the group reasons to feel confident, even as rumours of these meetings reached the Emir. Messages from von Hentig to Prince Henry, intercepted by British and Russian intelligence, were subsequently passed on to Emir Habibullah. These suggested that to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organise "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if necessary. Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. All of Afghanistan's immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah's father had died of unnatural causes. The fact that his immediate relatives were pro-German, while he was allied with Britain, gave him justifiable grounds to fear for his safety and his kingdom. Von Hentig described one audience with Habibullah where von Hentig set off his pocket alarm clock. The action, designed to impress Habibullah, instead frightened him; he may have believed it was a bomb about to go off. Despite von Hentig's reassurances and explanations, the meeting was a short one.

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central war effort with what has been described as "masterly inactivity". He waited for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India—if and when Turco-German troops were able to offer support. Hints that the mission would leave if nothing could be achieved were placated with flattery and invitations to stay on. Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty which was put to good use on a successful hearts and minds campaign, with expedition members spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct a hospital. Meanwhile, Kasim Bey acquainted himself with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad. Habibullah tolerated the increasingly anti-British and pro-Central tone being taken by his newspaper, ''Siraj al Akhbar'', whose editor—his father-in-law Mahmud Tarzi

Mahmud Tarzi ( ps, محمود طرزۍ, Dari: محمود بیگ طرزی; August 23, 1865 – November 22, 1933) was an Afghan politician and intellectual. He is known as the father of Afghan journalism. He became a key figure in the history of ...

—had accepted Barkatullah as an officiating editor in early 1916. Tarzi published a series of inflammatory articles by Raja Mahendra Pratap and printed anti-British and pro-Central articles and propaganda. By May 1916, the tone in the paper was deemed serious enough for the Raj to intercept the copies intended for India.

Through German links with Ottoman Turkey, the Berlin Committee at this time established contact with Mahmud al Hasan at Hijaz, while the expedition itself was now met at Kabul by Ubaidullah Sindhi's group.

Political developments

Political events and progress attained during December 1915 allowed the mission to celebrate at Kabul on Christmas Day with wine and cognac left behind by the Durand mission forty years previously, which Habibullah lay at their disposal. These events included the foundation of theProvisional Government of India

The Provisional Government of India was a provisional government-in-exile established in Kabul, Afghanistan on December 1, 1915 by the Indian Independence Committee during World War I with support from the Central Powers. Its purpose was to enr ...

that month and a shift from the Emir's usual aversive stance to an offer of discussions on a German-Afghan treaty of friendship.

In November, the Indian members decided to take a political initiative which they believed would convince the Emir to declare jihad, and if that proved unlikely, to have his hand forced by his advisors. On 1 December 1915, the Provisional Government of India was founded at Habibullah's Bagh-e-Babur Palace, in the presence of the Indian, German, and Turkish members of the expedition. This revolutionary government-in-exile was to take charge of an independent India when the British authority had been overthrown. Mahendra Pratap was proclaimed president, Barkatullah the prime minister, the Deobandi leader Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi the minister for India, Maulavi Bashir the war minister, and Champakaran Pillai the foreign minister. Support was obtained from Galib Pasha for proclaiming jihad against Britain, while recognition was sought from Russia, Republican China, and Japan. After the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, Pratap's government corresponded with the nascent Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

government in an attempt to gain their support. In 1918, Mahendra Pratap met Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian M ...

in Petrograd before meeting the Kaiser in Berlin, urging both to mobilise against British India.

Draft Afghan-German friendship treaty