Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with

free-market capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

after it fell into decline following the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

.

A prominent factor in the rise of

conservative and

libertarian organizations,

political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

, and

think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-govern ...

s, and predominantly advocated by them,

it is generally associated with policies of

economic liberalization, including

privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

,

deregulation,

globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

,

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

,

monetarism

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on nati ...

,

austerity, and reductions in

government spending in order to increase the role of the

private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy, sometimes referred to as the citizen sector, which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The ...

in the

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

and

society

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soc ...

. The defining features of neoliberalism in both thought and practice have been the subject of substantial scholarly debate.

As an

economic philosophy, neoliberalism emerged among European

liberal scholars in the 1930s as they attempted to revive and renew central ideas from

classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

as they saw these ideas diminish in popularity, overtaken by a desire to control markets, following the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and manifested in policies designed with the intention to counter the volatility of free markets.

One impetus for the formulation of policies to mitigate free-market volatility was a desire to avoid repeating the economic failures of the early 1930s, failures sometimes attributed principally to the

economic policy of classical liberalism. In policymaking, neoliberalism often refers to what was part of a

paradigm shift that followed the failure of the

Keynesian consensus in economics to address the

stagflation of the 1970s.

The collapse of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and the end of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

also made possible the triumph of neoliberalism in the United States and around the world.

The term has multiple, competing definitions, and a pejorative valence. English speakers have used the term since the start of the 20th century with different meanings,

but it became more prevalent in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, used by scholars in a wide variety of

social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of s ...

s

as well as by critics

[; "Friedman and Hayek are identified as the original thinkers and Thatcher and Reagan as the archetypal politicians of Western neoliberalism. Neoliberalism here has a pejorative connotation".] to describe the transformation of society in recent decades due to market-based reforms.

The term is rarely used by proponents of free-market policies. Some scholars reject the idea that neoliberalism is a monolithic ideology and have described the term as meaning different things to different people as neoliberalism has "mutated" into multiple, geopolitically distinct hybrids as it travelled around the world. Neoliberalism shares many attributes with other concepts that have contested meanings, including

representative democracy.

When the term entered into common use in the 1980s in connection with

Augusto Pinochet's

economic reforms in

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, it quickly took on negative connotations and was employed principally by critics of market reform and

laissez-faire capitalism. Scholars tended to associate it with the theories of

Mont Pelerin Society economists

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

,

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

,

Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, logician, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is ...

and

James M. Buchanan

James McGill Buchanan Jr. (; October 3, 1919 – January 9, 2013) was an American economist known for his work on public choice theory originally outlined in his most famous work co-authored with Gordon Tullock in 1962, ''The Calculus of Consen ...

, along with politicians and policy-makers such as

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

,

Ronald Reagan and

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He works as a private adviser and provides consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates LLC. ...

.

Once the new meaning of neoliberalism became established as a common usage among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of

political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

.

By 1994, with the passage of

NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA ; es, Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte, TLCAN; french: Accord de libre-échange nord-américain, ALÉNA) was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that crea ...

and with the

Zapatistas

Zapatista(s) may refer to:

* Liberation Army of the South, formed 1910s, a Mexican insurgent group involved in the Mexican Revolution

* Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), formed 1983, a Mexican indigenous armed revolutionary group based ...

' reaction to this development in

Chiapas, the term entered global circulation. Scholarship on the phenomenon of neoliberalism has grown over the last few decades.

Terminology

Origins

An early use of the term in English was in 1898 by the French economist

Charles Gide to describe the economic beliefs of the Italian economist

Maffeo Pantaleoni

Maffeo Pantaleoni (; Frascati, 2 July 1857Milan, 29 October 1924) was an Italian economist. At first he was a notable proponent of neoclassical economics. Later in his life, before and during World War I, he became an ardent nationalist and synd ...

, with the term previously existing in French,

and the term was later used by others including the classical liberal economist

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

in his 1951 essay "Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects".

In 1938 at the

Colloque Walter Lippmann

The Colloque Walter Lippmann ( English: Walter Lippmann Colloquium), was a conference of intellectuals organized in Paris in August 1938 by French philosopher Louis Rougier. After interest in classical liberalism had declined in the 1920s and 19 ...

, the term ''neoliberalism'' was proposed, among other terms, and ultimately chosen to be used to describe a certain set of economic beliefs.

The colloquium defined the concept of neoliberalism as involving "the priority of the price mechanism, free enterprise, the system of competition, and a strong and impartial state".

According to attendees

Louis Rougier

Louis Auguste Paul Rougier (; 10 April 1889 – 14 October 1982) was a French philosopher. Rougier made many important contributions to epistemology, philosophy of science, political philosophy and the history of Christianity.

Early life

Rougie ...

and

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

, the competition of neoliberalism would establish an

elite structure of successful individuals that would assume power in society, with these elites replacing the existing

representative democracy acting on the behalf of the majority. To be ''neoliberal'' meant advocating a modern economic policy with

state intervention

Economic interventionism, sometimes also called state interventionism, is an economic policy position favouring government intervention in the market process with the intention of correcting market failures and promoting the general welfare o ...

.

Neoliberal state interventionism brought a clash with the opposing ''laissez-faire'' camp of classical liberals, like

Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, logician, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is ...

. Most scholars in the 1950s and 1960s understood neoliberalism as referring to the social market economy and its principal economic theorists such as

Walter Eucken,

Wilhelm Röpke

Wilhelm Röpke (October 10, 1899 – February 12, 1966) was a German economist and social critic, best known as one of the spiritual fathers of the social market economy. A Professor of Economics, first in Jena, then in Graz, Marburg, Is ...

,

Alexander Rüstow and

Alfred Müller-Armack. Although Hayek had intellectual ties to the German neoliberals, his name was only occasionally mentioned in conjunction with neoliberalism during this period due to his more pro-free market stance.

During the

military rule under Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990) in Chile, opposition scholars took up the expression to describe the

economic reforms implemented there and its proponents (the

Chicago Boys

The Chicago Boys were a group of Chilean economists prominent around the 1970s and 1980s, the majority of whom were educated at the Department of Economics of the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger, or at its affiliat ...

).

Once this new meaning was established among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy.

According to one study of 148 scholarly articles, neoliberalism is almost never defined but used in several senses to describe ideology, economic theory, development theory, or economic reform policy. It has become used largely as a

term of abuse and/or to imply a ''laissez-faire''

market fundamentalism virtually identical to that of classical liberalism – rather than the ideas of those who attended the 1938 colloquium. As a result there is controversy as to the precise meaning of the term and its usefulness as a descriptor in the

social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of s ...

s, especially as the number of different kinds of market economies have proliferated in recent years.

Unrelated to the economic philosophy described in this article, the term "neoliberalism" is also used to describe a center-left political movement from

modern American liberalism

Modern liberalism in the United States, often simply referred to in the United States as liberalism, is a form of social liberalism found in American politics. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice and ...

in the 1970s. According to political commentator

David Brooks, prominent neoliberal politicians included

Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic ...

and

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

of the Democratic Party of the United States. The neoliberals coalesced around two magazines, ''

The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'' and the ''

Washington Monthly

''Washington Monthly'' is a bimonthly, nonprofit magazine of United States politics and government that is based in Washington, D.C. The magazine is known for its annual ranking of American colleges and universities, which serves as an alternat ...

'', and often supported

Third Way policies. The "godfather" of this version of neoliberalism was the journalist

Charles Peters

Charles Peters (born December 22, 1926) is an American journalist, editor, and author. He was the founder and editor-in-chief of the ''Washington Monthly'' magazine and the author of ''We Do Our Part: Toward A Fairer and More Equal America'' ( R ...

, who in 1983 published "A Neoliberal's Manifesto".

Current usage

Historian Elizabeth Shermer argued that the term gained popularity largely among left-leaning academics in the 1970s to "describe and decry a late twentieth-century effort by policy makers, think-tank experts, and industrialists to condemn social-democratic reforms and unapologetically implement free-market policies"; economic historian Phillip W. Magness notes its reemergence in academic literature in the mid-1980s, after French philosopher

Michel Foucault brought attention to it.

''Neoliberalism'' is contemporarily used to refer to market-oriented reform policies such as "eliminating

price control

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of good ...

s,

deregulating

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

capital markets, lowering

trade barriers" and reducing, especially through

privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

and

austerity, state influence in the economy.

It is also commonly associated with the economic policies introduced by

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

in the United Kingdom and

Ronald Reagan in the United States.

Some scholars note it has a number of distinct usages in different spheres:

* As a

development model, it refers to the rejection of

structuralist economics in favor of the

Washington Consensus.

* As an

ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

, it denotes a conception of freedom as an overarching

social value associated with reducing state functions to those of a

minimal state.

* As a

public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public ...

, it involves the privatization of public economic sectors or services, the deregulation of private corporations, sharp decrease of

government budget deficit

The government budget balance, also alternatively referred to as general government balance, public budget balance, or public fiscal balance, is the overall difference between government revenues and spending. A positive balance is called a ''g ...

s and reduction of spending on

public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, sc ...

.

There is, however, debate over the meaning of the term. Sociologists

Fred L. Block

Fred L. Block (born June 28, 1947) is an American sociologist, and Research Professor of Sociology at UC-Davis. Block is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading economic and political sociologists. His interests are wide ranging. He has ...

and

Margaret Somers

Margaret R. Somers is an American sociologist and Professor of Sociology and History at the University of Michigan She is the recipient of the inaugural Lewis A. Coser Award for Innovation and Theoretical Agenda-Setting in Sociology, Somers's wor ...

claim there is a dispute over what to call the influence of free-market ideas which have been used to justify the retrenchment of

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs and policies since the 1980s: neoliberalism, ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' or "free market ideology". Other academics such as Susan Braedley and Med Luxton assert that neoliberalism is a political philosophy which seeks to "liberate" the processes of

capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form ...

.

[Susan Braedley and Meg Luxton, ]

Neoliberalism and Everyday Life

'' ( McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010),

p. 3

/ref> In contrast, Frances Fox Piven sees neoliberalism as essentially hyper-capitalism. However, Robert W. McChesney, while defining neoliberalism similarly as "capitalism with the gloves off", goes on to assert that the term is largely unknown by the general public, particularly in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.[ Chomsky, Noam and McChesney, Robert W. (Introduction). '' Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order.'' ]Seven Stories Press

Seven Stories Press is an independent American publishing company. Based in New York City, the company was founded by Dan Simon in 1995, after establishing Four Walls Eight Windows in 1984 as an imprint at Writers and Readers, and then incorpo ...

, 2011.

/ref> Lester Spence

Lester K. Spence (born June 5, 1969), Professor of Political Science and Africana studies at Johns Hopkins University is known for his academic critiques of neoliberalism and his media commentary and research on race, urban politics, and police v ...

uses the term to critique trends in Black politics, defining neoliberalism as "the general idea that society works best when the people and the institutions within it work or are shaped to work according to market principles". According to Philip Mirowski

Philip Mirowski (born 21 August 1951 in Jackson, Michigan) is a historian and philosopher of economic thought at the University of Notre Dame. He received a PhD in Economics from the University of Michigan in 1979.

Career

In his 1989 book ''More ...

, neoliberalism views the market as the greatest information processor superior to any human being. It is hence considered as the arbiter of truth. Adam Kotsko

Adam Kotsko (born 1980) is an American theologian, religious scholar, culture critic, and translator, working in the field of political theology. He served as an Assistant Professor of Humanities at Shimer College in Chicago, which was absorbed in ...

describes neoliberalism as political theology

Political theology is a term which has been used in discussion of the ways in which theological concepts or ways of thinking relate to politics. The term ''political theology'' is often used to denote religious thought about political principled qu ...

, as it goes beyond simply being a formula for economic policy agenda and instead infuses it with a moral ethos that "aspires to be a complete way of life and a holistic worldview, in a way that previous models of capitalism did not."Jason Hickel

Jason Edward Hickel (born 1982) is an economic anthropologist whose research focuses on ecological economics, global inequality, imperialism and political economy. He is known for his books ''The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and ...

also rejects the notion that neoliberalism necessitates the retreat of the state in favor of totally free markets, arguing that the spread of neoliberalism required substantial state intervention to establish a global 'free market'. Naomi Klein

Naomi A. Klein (born May 8, 1970) is a Canadian author, social activist, and filmmaker known for her political analyses, support of ecofeminism, organized labour, left-wing politics and criticism of corporate globalization, fascism, ecofascism ...

states that the three policy pillars of neoliberalism are "privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

of the public sphere, deregulation of the corporate sector, and the lowering of income

Income is the consumption and saving opportunity gained by an entity within a specified timeframe, which is generally expressed in monetary terms. Income is difficult to define conceptually and the definition may be different across fields. Fo ...

and corporate taxes

A corporate tax, also called corporation tax or company tax, is a direct tax imposed on the income or capital of corporations or analogous legal entities. Many countries impose such taxes at the national level, and a similar tax may be imposed ...

, paid for with cuts to public spending".

Neoliberalism is also, according to some scholars, commonly used as a pejorative

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

by critics, outpacing similar terms such as monetarism

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on nati ...

, neoconservatism

Neoconservatism is a political movement that began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist foreign policy of the Democratic Party and with the growing New Left and co ...

, the Washington Consensus and "market reform" in much scholarly writing.[David M Kotz, ]

The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism

'' (Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retir ...

, 2015), The ''Handbook'', for example, further argues that "such lack of specificity or the termreduces its capacity as an analytic frame. If neoliberalism is to serve as a way of understanding the transformation of society over the last few decades then the concept is in need of unpacking".The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', Stephen Metcalf posits that the publication of the 2016 IMF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glob ...

paper "Neoliberalism: Oversold?"

Early history

Walter Lippmann Colloquium

The

The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

in the 1930s, which severely decreased economic output throughout the world and produced high unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

and widespread poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse , was widely regarded as a failure of economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic libera ...

. To renew the damaged ideology, a group of 25 liberal intellectuals, including a number of prominent academics and journalists like Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

, Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

, Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, logician, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is ...

, Wilhelm Röpke

Wilhelm Röpke (October 10, 1899 – February 12, 1966) was a German economist and social critic, best known as one of the spiritual fathers of the social market economy. A Professor of Economics, first in Jena, then in Graz, Marburg, Is ...

, Alexander Rüstow, and Louis Rougier

Louis Auguste Paul Rougier (; 10 April 1889 – 14 October 1982) was a French philosopher. Rougier made many important contributions to epistemology, philosophy of science, political philosophy and the history of Christianity.

Early life

Rougie ...

, organized the Walter Lippmann Colloquium, named in honor of Lippman to celebrate the publication of the French translation of Lippmann's pro- market book ''An Inquiry into the Principles of the Good Society''.[ Oliver Marc Hartwich]

Neoliberalism: The Genesis of a Political Swearword

Centre for Independent Studies, 2009, They further agreed to develop the Colloquium into a permanent think tank based in Paris called the Centre International d'Études pour la Rénovation du Libéralisme.

While most agreed that the ''status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. ...

'' liberalism promoting ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' economics had failed, deep disagreements arose around the proper role of the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

. A group of "true (third way) neoliberals" centered around Rüstow and Lippmann advocated for strong state supervision of the economy while a group of old school liberals centered around Mises and Hayek continued to insist that the only legitimate role for the state was to abolish barriers to market entry. Rüstow wrote that Hayek and Mises were relics of the liberalism that caused the Great Depression while Mises denounced the other faction, complaining that the ordoliberalism

Ordoliberalism is the German variant of economic liberalism that emphasizes the need for government to ensure that the free market produces results close to its theoretical potential but does not advocate for a welfare state.

Ordoliberal ideals ...

they advocated really meant "ordo-interventionism".Wilhelm Röpke

Wilhelm Röpke (October 10, 1899 – February 12, 1966) was a German economist and social critic, best known as one of the spiritual fathers of the social market economy. A Professor of Economics, first in Jena, then in Graz, Marburg, Is ...

to establish a journal of neoliberal ideas, mostly floundered.World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and were largely forgotten.[ ] However, the Colloquium did serve as the first meeting of the nascent "neoliberal" movement and would serve as the precursor to the Mont Pelerin Society, a far more successful effort created after the war by many of those who had been present at the Colloquium.

Mont Pelerin Society

Neoliberalism began accelerating in importance with the establishment of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, whose founding members included Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

, Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

, Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

, George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

and Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, logician, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is ...

. Meeting annually, it became a "kind of international 'who's who' of the classical liberal and neo-liberal intellectuals." While the first conference in 1947 was almost half American, the Europeans dominated by 1951. Europe would remain the epicenter of the community as Europeans dominated the leadership roles.central planning

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, pa ...

was in the ascendancy worldwide and there were few avenues for neoliberals to influence policymakers, the society became a "rallying point" for neoliberals, as Milton Friedman phrased it, bringing together isolated advocates of liberalism and capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

. They were united in their belief that individual freedom in the developed world was under threat from collectivist trends, which they outlined in their statement of aims:

The central values of civilization are in danger. Over large stretches of the Earth's surface the essential conditions of human dignity and freedom have already disappeared. In others, they are under constant menace from the development of current tendencies of policy. The position of the individual and the voluntary group are progressively undermined by extensions of arbitrary power. Even that most precious possession of Western Man, freedom of thought and expression, is threatened by the spread of creeds which, claiming the privilege of tolerance when in the position of a minority, seek only to establish a position of power in which they can suppress and obliterate all views but their own...The group holds that these developments have been fostered by the growth of a view of history which denies all absolute moral standards and by the growth of theories which question the desirability of the rule of law. It holds further that they have been fostered by a decline of belief in private property and the competitive market... his group'sobject is solely, by facilitating the exchange of views among minds inspired by certain ideals and broad conceptions held in common, to contribute to the preservation and improvement of the free society.

The society set out to develop a neoliberal alternative to, on the one hand, the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economic consensus that had collapsed with the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and, on the other, New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

liberalism and British social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

, collectivist trends which they believed posed a threat to individual freedom. They believed that classical liberalism had failed because of crippling conceptual flaws which could only be diagnosed and rectified by withdrawing into an intensive discussion group of similarly minded intellectuals;individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

and economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the l ...

must not be abandoned to collectivism.

Post–World War II neoliberal currents

For decades after the formation of the Mont Pelerin Society, the ideas of the society would remain largely on the fringes of political policy, confined to a number of think-tanks and universitiesGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, who maintained the need for strong state influence in the economy. It would not be until a succession of economic downturns and crises in the 1970s that neoliberal policy proposals would be widely implemented. By this time, however, neoliberal thought had evolved. The early neoliberal ideas of the Mont Pelerin Society had sought to chart a middle way between the trend of increasing government intervention implemented after the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economics many in the society believed had produced the Great Depression. Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

, for instance, wrote in his early essay "Neo-liberalism and Its Prospects" that "Neo-liberalism would accept the nineteenth-century liberal emphasis on the fundamental importance of the individual, but it would substitute for the nineteenth century goal of ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' as a means to this end, the goal of the competitive order", which requires limited state intervention to "police the system, establish conditions favorable to competition and prevent monopoly, provide a stable monetary framework, and relieve acute misery and distress". But by the 1970s, neoliberal thought—including Friedman's—focused almost exclusively on market liberalization

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

and was adamant in its opposition to nearly all forms of state interference in the economy.

One of the earliest and most influential turns to neoliberal reform occurred in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

after an economic crisis in the early 1970s. After several years of socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

economic policies under president Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (, , ; 26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean physician and socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 3 November 1970 until his death on 11 September 1973. He was the fir ...

, a 1973 ''coup d'état'', which established a military junta

A military junta () is a government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the national and local junta organized by the Spanish resistance to Napoleon's invasion of Spain in ...

under dictator Augusto Pinochet, led to the implementation of a number of sweeping neoliberal economic reforms that had been proposed by the Chicago Boys

The Chicago Boys were a group of Chilean economists prominent around the 1970s and 1980s, the majority of whom were educated at the Department of Economics of the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger, or at its affiliat ...

, a group of Chilean economists educated under Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

. This "neoliberal project" served as "the first experiment with neoliberal state formation" and provided an example for neoliberal reforms elsewhere.Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

and Thatcher government implemented a series of neoliberal economic reforms to counter the chronic stagflation the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

had each experienced throughout the 1970s. Neoliberal policies continued to dominate American and British politics until the Great Recession

The Great Recession was a period of marked general decline, i.e. a recession, observed in national economies globally that occurred from late 2007 into 2009. The scale and timing of the recession varied from country to country (see map). At ...

. Following British and American reform, neoliberal policies were exported abroad, with countries in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

, the Asia-Pacific

Asia-Pacific (APAC) is the part of the world near the western Pacific Ocean. The Asia-Pacific region varies in area depending on context, but it generally includes East Asia, Russian Far East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia and Paci ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and even communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

implementing significant neoliberal reform. Additionally, the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

and World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

encouraged neoliberal reforms in many developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

by placing reform requirements on loans, in a process known as structural adjustment

Structural adjustment programs (SAPs) consist of loans (structural adjustment loans; SALs) provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) to countries that experience economic crises. Their purpose is to adjust the co ...

.

Germany

Neoliberal ideas were first implemented in

Neoliberal ideas were first implemented in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

. The economists around Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard (; 4 February 1897 – 5 May 1977) was a German politician affiliated with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and chancellor of West Germany from 1963 until 1966. He is known for leading the West German postwar economic ...

drew on the theories they had developed in the 1930s and 1940s and contributed to West Germany's reconstruction after the Second World War. Erhard was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society and in constant contact with other neoliberals. He pointed out that he is commonly classified as neoliberal and that he accepted this classification.

The ordoliberal Freiburg School

__notoc__

The Freiburg school (german: Freiburger Schule) is a school of History of economic thought, economic thought founded in the 1930s at the University of Freiburg.

It builds somewhat on the earlier historical school of economics but stresse ...

was more pragmatic. The German neoliberals accepted the classical liberal notion that competition drives economic prosperity, but they argued that a laissez-faire state policy stifles competition, as the strong devour the weak since monopolies and cartels could pose a threat to freedom of competition. They supported the creation of a well-developed legal system and capable regulatory apparatus. While still opposed to full-scale Keynesian employment policies or an extensive welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

, German neoliberal theory was marked by the willingness to place humanistic

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and social values on par with economic efficiency. Alfred Müller-Armack coined the phrase "social market economy" to emphasize the egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

and humanistic bent of the idea. Erhard emphasized that the market was inherently social and did not need to be made so.

Erhard emphasized that the market was inherently social and did not need to be made so.Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

. Rüstow, who had coined the label "neoliberalism", criticized that development tendency and pressed for a more limited welfare program.social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals ...

was a muddle of inconsistent aims. Despite his controversies with the German neoliberals at the Mont Pelerin Society, Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, logician, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is ...

stated that Erhard and Müller-Armack accomplished a great act of liberalism to restore the German economy and called this "a lesson for the US". However, according to different research Mises believed that the ordoliberals were hardly better than socialists. As an answer to Hans Hellwig's complaints about the interventionist excesses of the Erhard ministry and the ordoliberals, Mises wrote: "I have no illusions about the true character of the politics and politicians of the social market economy". According to Mises, Erhard's teacher Franz Oppenheimer

Franz Oppenheimer (March 30, 1864 – September 30, 1943) was a German Jewish sociologist and political economist, who published also in the area of the fundamental sociology of the state.

Life and career

After studying medicine in Freiburg and ...

"taught more or less the New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as the ...

line of" President Kennedy's "Harvard consultants (Schlesinger Schlesinger is a German surname (in part also Jewish) meaning "Silesian" from the older regional term ''Schlesinger''; someone from ''Schlesing'' (Silesia); in modern Standard German (or Hochdeutsch) a '' Schlesier'' is someone from '' Schlesien'' ...

, Galbraith, etc.)".

In Germany, neoliberalism at first was synonymous with both ordoliberalism and social market economy. But over time the original term neoliberalism gradually disappeared since social market economy was a much more positive term and fit better into the ''Wirtschaftswunder

The ''Wirtschaftswunder'' (, "economic miracle"), also known as the Miracle on the Rhine, was the rapid reconstruction and development of the economies of West Germany and Austria after World War II (adopting an ordoliberalism-based social ma ...

'' (economic miracle) mentality of the 1950s and 1960s.

Latin America

In the 1980s, numerous governments in Latin America adopted neoliberal policies.

Chile

Chile was among the earliest nations to implement neoliberal reform. Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

economic geographer David Harvey

David W. Harvey (born 31 October 1935) is a British-born Marxist economic geographer, podcaster and Distinguished Professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY). He received his P ...

has described the substantial neoliberal reforms in Chile beginning in the 1970s as "the first experiment with neoliberal state formation", which would provide "helpful evidence to support the subsequent turn to neoliberalism in both Britain... and the United States."Vincent Bevins

Vincent Bevins is an American journalist and writer. From 2011 to 2016, he worked as a foreign correspondent based in Brazil for the ''Los Angeles Times'', after working previously in London for the ''Financial Times''. In 2017 he moved to Jakart ...

says that Chile under Augusto Pinochet "became the world's first test case for 'neoliberal' economics."

The turn to neoliberal policies in Chile originated with the Chicago Boys

The Chicago Boys were a group of Chilean economists prominent around the 1970s and 1980s, the majority of whom were educated at the Department of Economics of the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger, or at its affiliat ...

, a select group of Chilean students who, beginning in 1955, were invited to the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

to pursue postgraduate studies in economics. They studied directly under Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and his disciple, Arnold Harberger

Arnold Carl Harberger (born July 27, 1924) is an American economist. His approach to the teaching and practice of economics is to emphasize the use of analytical tools that are directly applicable to real-world issues. His influence on academic ec ...

, and were exposed to Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

. Upon their return to Chile, their neoliberal policy proposals—which centered on widespread deregulation, privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

, reductions to government spending to counter high inflation, and other free-market policies—would remain largely on the fringes of Chilean economic and political thought for a number of years, as the presidency of Salvador Allende

Salvador Allende was the president of Chile from 1970 until his 1973 suicide, and head of the Popular Unity government; he was a Socialist and Marxist elected to the national presidency of a liberal democracy in Latin America.Don MabryAllend ...

(1970–1973) brought about a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

reorientation of the economy.

During the Allende presidency, Chile experienced a severe economic crisis, in which inflation peaked near 150%.

During the Allende presidency, Chile experienced a severe economic crisis, in which inflation peaked near 150%.United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, the Chilean armed forces and national police overthrew the Allende government in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

. They established a repressive military ''junta'', known for its violent suppression of opposition, and appointed army chief Augusto Pinochet Supreme Head of the nation. His rule was later given legal legitimacy through a controversial 1980 plebiscite, which approved a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

drafted by a government-appointed commission that ensured Pinochet would remain as President for a further eight years—with increased powers—after which he would face a re-election referendum.military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a dictatorship in which the military exerts complete or substantial control over political authority, and the dictator is often a high-ranked military officer.

The reverse situation is to have civilian control of the ...

, and they implemented sweeping economic reform. In contrast to the extensive nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

and centrally planned economic programs supported by Allende, the Chicago Boys implemented rapid and extensive privatization of state enterprises, deregulation, and significant reductions in trade barriers during the latter half of the 1970s. In 1978, policies that would further reduce the role of the state and infuse competition and individualism into areas such as labor relations, pensions, health and education were introduced. These policies amounted to a shock therapy, which rapidly transformed Chile from an economy with a protected market and strong government intervention into a liberalized, world-integrated economy, where market forces were left free to guide most of the economy's decisions.

These policies amounted to a shock therapy, which rapidly transformed Chile from an economy with a protected market and strong government intervention into a liberalized, world-integrated economy, where market forces were left free to guide most of the economy's decisions.Latin American debt crisis

The Latin American debt crisis ( es, Crisis de la deuda latinoamericana; pt, Crise da dívida latino-americana) was a financial crisis that originated in the early 1980s (and for some countries starting in the 1970s), often known as ''La Déca ...

—which swept nearly all of Latin America into financial crisis—was a primary cause.[''Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores''. 2002. ]Gabriel Salazar

Gabriel Salazar Vergara (born 31 January 1936) is a Chilean historian. He is known in his country for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements, particularly the recent student protests of 2006 and 2011–12.

Salazar ...

and Julio Pinto

Julio Pinto Vallejos (born 1956) is a Chilean historian. He is known in Chile for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements. In 2016 he won the Chilean National History Award. He is a member of the editorial board of LOM ...

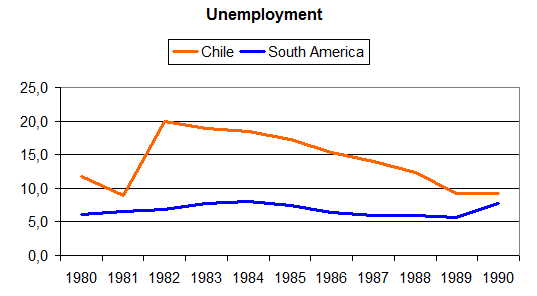

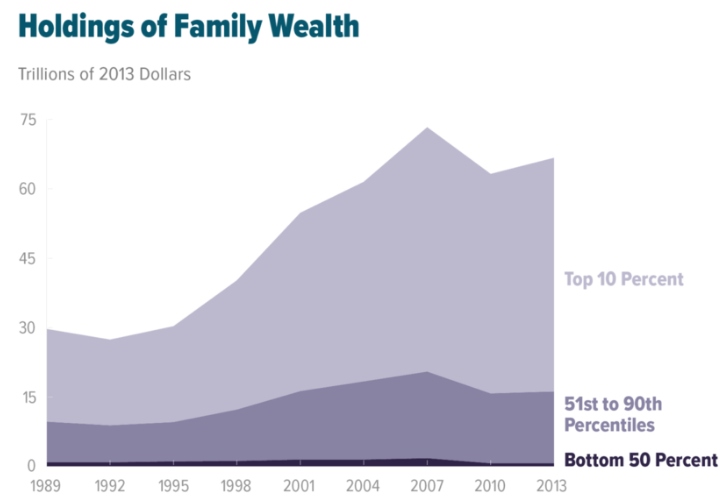

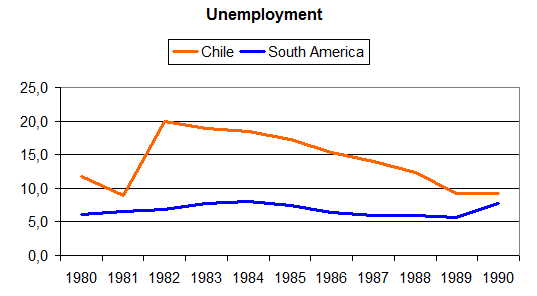

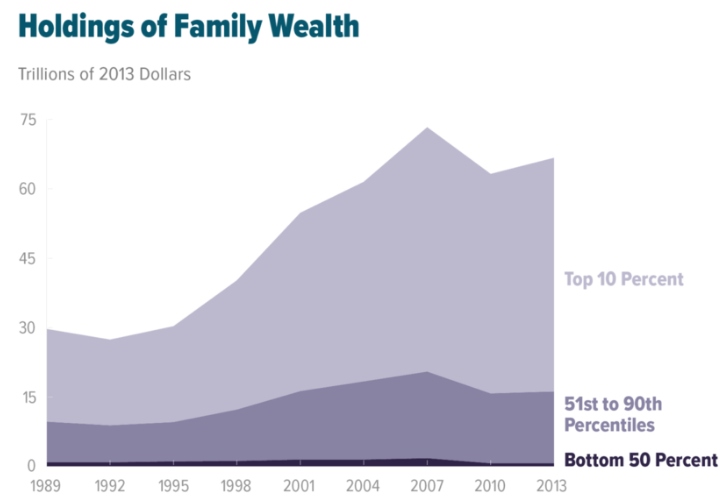

. pp. 49–-62. Some scholars argue the neoliberal policies of the Chicago boys heightened the crisis (for instance, percent GDP decrease was higher than in any other Latin American country) or even caused it; After the recession, Chilean economic growth rose quickly, eventually hovering between 5% and 10% and significantly outpacing the Latin American average (see chart). Additionally, unemployment decreased and the percent of the population below the poverty line declined from 50% in 1984 to 34% by 1989.

After the recession, Chilean economic growth rose quickly, eventually hovering between 5% and 10% and significantly outpacing the Latin American average (see chart). Additionally, unemployment decreased and the percent of the population below the poverty line declined from 50% in 1984 to 34% by 1989.Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

to call the period the " Miracle of Chile", and he attributed the successes to the neoliberal policies of the Chicago boys. Some scholars, however, attribute the successes to the re-regulation of the banking industry and a number of targeted social programs designed to alleviate poverty.[ Others note that while the economy had stabilized and was growing by the late 1980s, inequality widened: nearly 45% of the population had fallen into poverty while the wealthiest 10% had seen their incomes rise by 83%. According to Chilean economist ]Alejandro Foxley

Alejandro Tomás Foxley Rioseco (born 26 May 1939 in Viña del Mar) is a Chilean economist and politician. He was the Foreign Minister of Chile from 2006 to 2009 and previously served as Minister of Finance from 1990 to 1994 and leader of the Ch ...

, when Pinochet finished his 17-year term by 1990, around 44% of Chilean families were living below the poverty line.

Despite years of suppression by the Pinochet junta, in 1988 a presidential election was held, as dictated by the 1980 constitution (though not without Pinochet first holding another plebiscite in an attempt to amend the constitution).[ In 1990, ]Patricio Aylwin

Patricio Aylwin Azócar (; 26 November 1918 – 19 April 2016) was a Chilean politician from the Christian Democratic Party, lawyer, author, professor and former senator. He was the first president of Chile after dictator Augusto Pinochet, a ...

was democratically elected, bringing an end to the military dictatorship. The reasons cited for Pinochet's acceptance of democratic transition are numerous. Hayek, echoing arguments he had made years earlier in ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' (German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

,''Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

, ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' (German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

'', University of Chicago Press; 50th Anniversary edition (1944), p. 95elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (french: élite, from la, eligere, to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. ...

s to use existing institutional mechanisms to restore democracy.

In the 1990s, neoliberal economic policies broadened and deepened, including unilateral tariff reductions and the adoption of free trade agreements with a number of Latin American countries and Canada.

In the 1990s, neoliberal economic policies broadened and deepened, including unilateral tariff reductions and the adoption of free trade agreements with a number of Latin American countries and Canada.[ Eduardo Aninat, writing for the IMF journal ''Finance & Development'', called the period from 1986 to 2000 "the longest, strongest, and most stable period of growth in hile'shistory."][ In 1999 there was a brief recession brought about by the ]Asian financial crisis

The Asian financial crisis was a period of financial crisis that gripped much of East Asia and Southeast Asia beginning in July 1997 and raised fears of a worldwide economic meltdown due to financial contagion. However, the recovery in 1998– ...

, with growth resuming in 2000 and remaining near 5% until the Great Recession

The Great Recession was a period of marked general decline, i.e. a recession, observed in national economies globally that occurred from late 2007 into 2009. The scale and timing of the recession varied from country to country (see map). At ...

.

In sum, the neoliberal policies of the 1980s and 1990s—initiated by a repressive authoritarian government—transformed the Chilean economy from a protected market with high barriers to trade

Trade barriers are government-induced restrictions on international trade. According to the theory of comparative advantage, trade barriers are detrimental to the world economy and decrease overall economic efficiency.

Most trade barriers work o ...

and hefty government intervention

Economic interventionism, sometimes also called state interventionism, is an economic policy position favouring government intervention in the market process with the intention of correcting market failures and promoting the general welfare of ...

into one of the world's most open

Open or OPEN may refer to:

Music

* Open (band), Australian pop/rock band

* The Open (band), English indie rock band

* Open (Blues Image album), ''Open'' (Blues Image album), 1969

* Open (Gotthard album), ''Open'' (Gotthard album), 1999

* Open (C ...

free-market economies.Latin American debt crisis

The Latin American debt crisis ( es, Crisis de la deuda latinoamericana; pt, Crise da dívida latino-americana) was a financial crisis that originated in the early 1980s (and for some countries starting in the 1970s), often known as ''La Déca ...

(several years into neoliberal reform), but also had one of the most robust recoveries,[ rising from the poorest Latin American country in terms of ]GDP per capita

Lists of countries by GDP per capita list the countries in the world by their gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. The lists may be based on nominal or purchasing power parity GDP. Gross national income (GNI) per capita accounts for inflo ...

in 1980 (along with Peru) to the richest in 2019.infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of young children under the age of 1. This death toll is measured by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the probability of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births. The under-five morta ...

rate in Chile fell from 76.1 per 1000 to 22.6 per 1000,OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate ...

, an organization of mostly developed countries

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

that includes Chile but not most other Latin American countries. Furthermore, the Gini coefficient measures only income inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of we ...

; Chile has more mixed inequality ratings in the OECD's Better Life Index

The OECD Better Life Index, created in May 2011 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, is an initiative pioneering the development of economic indicators which better capture multiple dimensions of economic and social progr ...

, which includes indexes for more factors than only income, like housing

Housing, or more generally, living spaces, refers to the construction and assigned usage of houses or buildings individually or collectively, for the purpose of shelter. Housing ensures that members of society have a place to live, whether ...

and education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

.CIA World Factbook

''The World Factbook'', also known as the ''CIA World Factbook'', is a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with almanac-style information about the countries of the world. The official print version is available ...

states that Chile's "sound economic policies", maintained consistently since the 1980s, "have contributed to steady economic growth in Chile and have more than halved poverty rates,"[Chile](_blank)

''The World Factbook

''The World Factbook'', also known as the ''CIA World Factbook'', is a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with almanac-style information about the countries of the world. The official print version is availabl ...

''. Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. and some scholars have even called the period the " Miracle of Chile". Other scholars, however, have called it a failure that led to extreme inequalities in the distribution of income and resulted in severe socioeconomic damage.[ in particular, some scholars argue that after the Crisis of 1982 the "pure" neoliberalism of the late 1970s was replaced by a focus on fostering a ]social market economy

The social market economy (SOME; german: soziale Marktwirtschaft), also called Rhine capitalism, Rhine-Alpine capitalism, the Rhenish model, and social capitalism, is a socioeconomic model combining a free-market capitalist economic system alon ...

that mixed neoliberal and social welfare policies.Chilean constitution

The Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile of 1980 () is the fundamental law in force in Chile. It was approved and promulgated under the military dictatorship headed by Augusto Pinochet, being ratified by the Chilean citizenry throug ...

would be rewritten. The "approve" option for a new constitution to replace the Pinochet-era constitution, which entrenched certain neoliberal principles into the country's basic law, won with 78% of the vote.

Peru

Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

, the founder of one of the first neoliberal organizations in Latin America, Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), began to receive assistance from Ronald Reagan's administration, with the National Endowment for Democracy

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is an organization in the United States that was founded in 1983 for promoting democracy in other countries by promoting political and economic institutions such as political groups, trade unions, ...

's Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) providing his ILD with funding.President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Alan García

Alan Gabriel Ludwig García Pérez (; 23 May 1949 – 17 April 2019) was a Peruvian politician who served as President of Peru for two non-consecutive terms from 1985 to 1990 and from 2006 to 2011. He was the second leader of the Peruvian Apri ...