Nationalist Clubs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nationalist Clubs were an organized network of

Nationalist Clubs were an organized network of

In 1888, a young

In 1888, a young

Looking Backward, 2000-1887

'' telling the

First steps were taken into politics in the fall of 1890, with a Nationalist state ticket put forward in the state of

First steps were taken into politics in the fall of 1890, with a Nationalist state ticket put forward in the state of

Bellamy continued to work on behalf of the Nationalist movement through 1894, authoring a document entitled ''The Programme of the Nationalists'', which was published in the intellectual journal ''The Forum'' in March of that year. In this document, reprinted by the central publishing house of the Nationalist Clubs based in Philadelphia, Bellamy argued that

Bellamy continued to work on behalf of the Nationalist movement through 1894, authoring a document entitled ''The Programme of the Nationalists'', which was published in the intellectual journal ''The Forum'' in March of that year. In this document, reprinted by the central publishing house of the Nationalist Clubs based in Philadelphia, Bellamy argued that

Vol. 1 (1889)

Vol. 2 (1890)

Vol. 3 (1891)

* ''The New Nation'' (1891–1894) ** Vol. 1 (1891) , Vol. 2 (1892)

Vol. 3 (1893)

, Vol. 4 (1894)

''Looking Backward, 2000-1887.''

Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1889.

''Equality.''

New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1898.

''Looking Forward,''

vol. 1, no. 2 (September 1889), National City, California.

''Principles and Purposes of Nationalism: Edward Bellamy's Address at Tremont Temple, Boston, on the Nationalist Club's First Anniversary, December 19, 1889.''

Philadelphia: Bureau of Nationalist Literature, n.d. * Edward Bellamy

''The Programme of the Nationalists.''

Philadelphia: Bureau of Nationalist Literature, 1894. —First published in ''The Forum,'' March 1894.

''Reality; or, Law and Order vs. Anarchy and Socialism: A Reply to Edward Bellamy's Looking backward and Equality.''

Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1898.

"Nationalism,"

''The Arena,'' vol. 1, whole no. 2 (January 1890), pp. 153–165. * James J. Kopp, "Looking Backward at Edward Bellamy's Influence in Oregon, 1888-1936," ''Oregon Historical Quarterly,'' vol. 104, no. 1 (Spring 2003). * Everett W. MacNair, ''Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist Movement, 1889 to 1894: A Research Study of Edward Bellamy's Work as a Social Reformer.'' Milwaukee, WI: Fitzgerald Co., 1957. * Daphne Patai (ed.), ''Looking Backward, 1988-1888: Essays on Edward Bellamy.'' Amherst, MA:

Nationalist Clubs were an organized network of

Nationalist Clubs were an organized network of socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

political groups which emerged at the end of the 1880s in the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

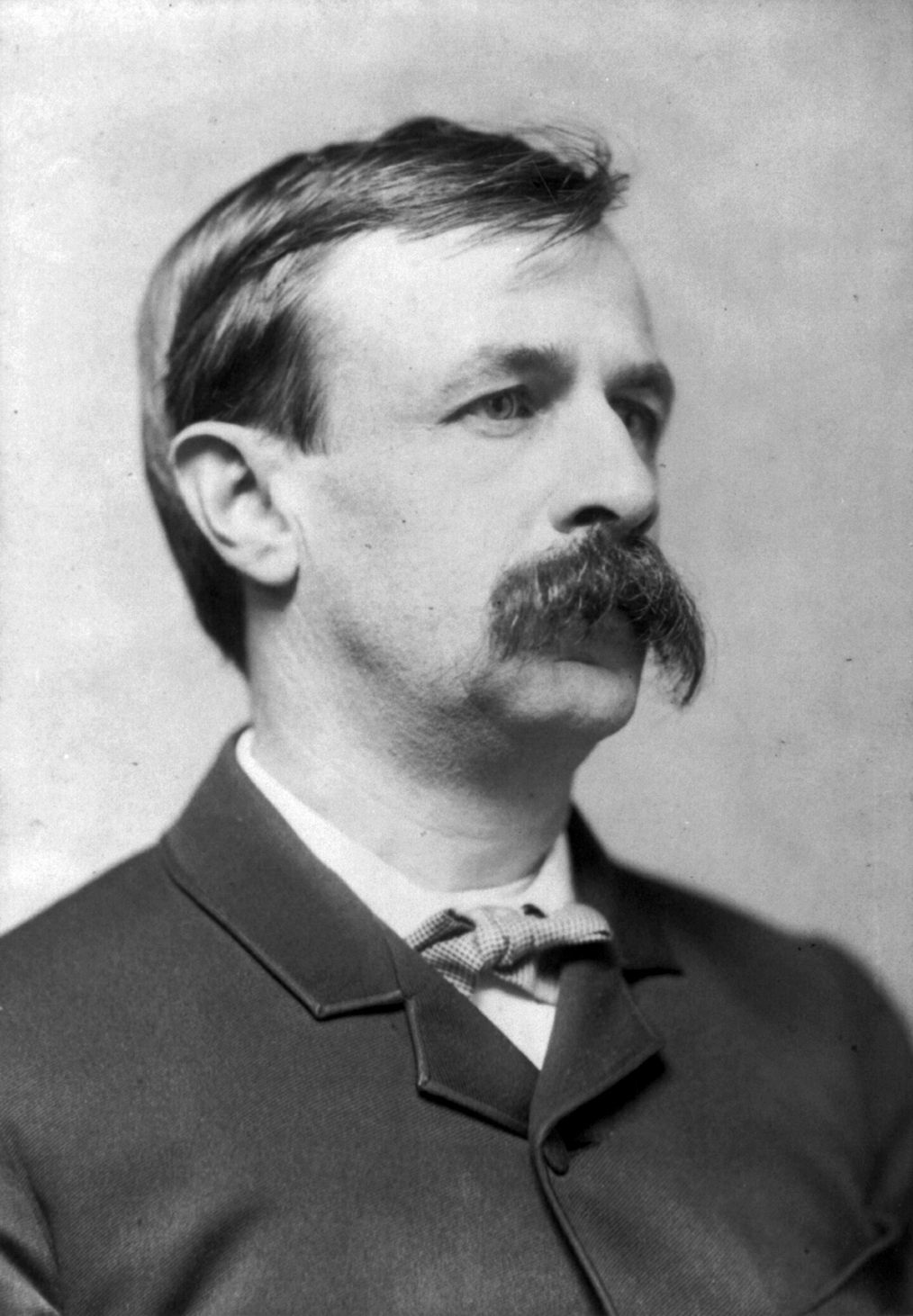

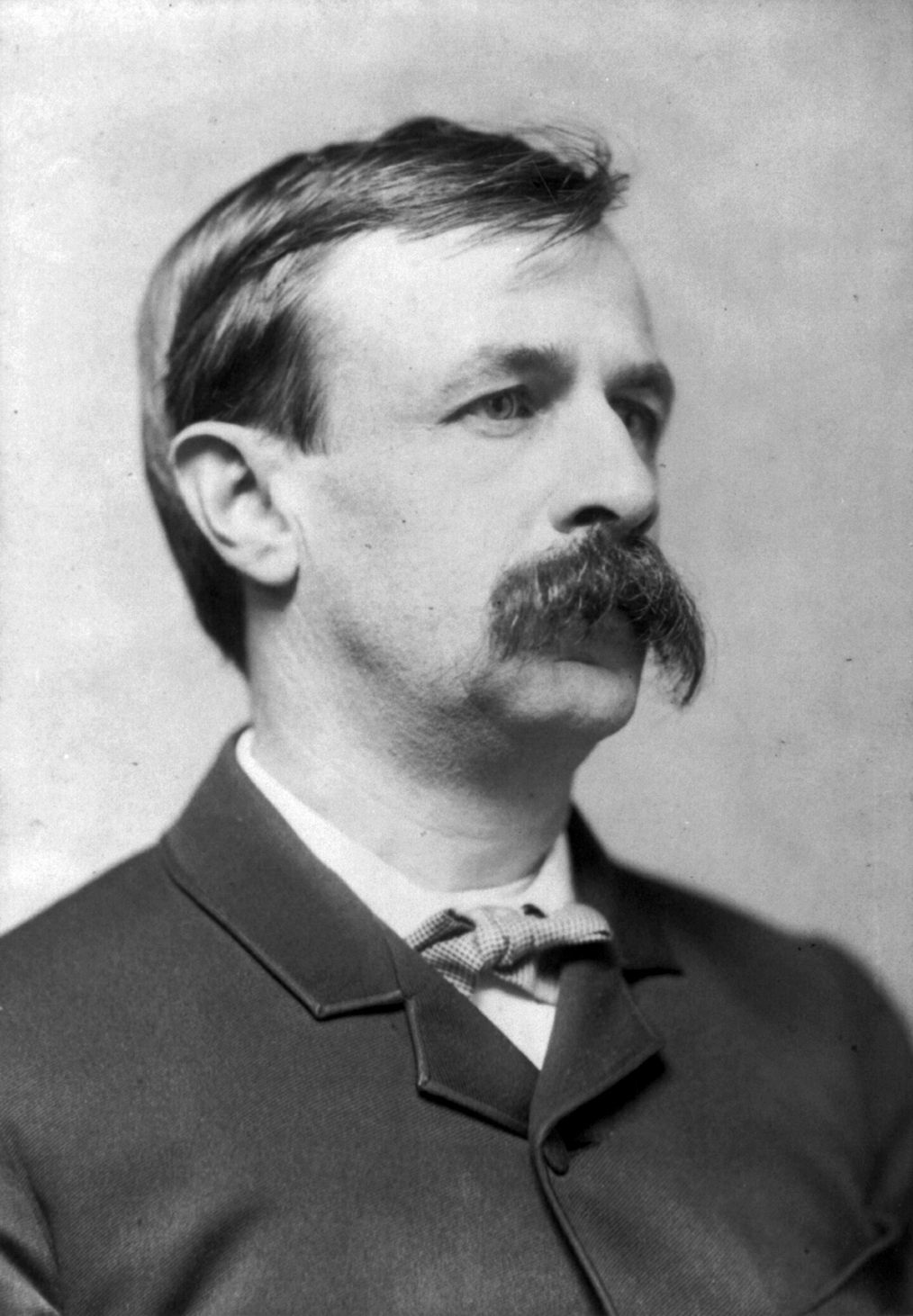

in an effort to make real the ideas advanced by Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

in his utopian

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia'', describing a fictional island society ...

novel ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

.'' At least 165 Nationalist Clubs were formed by so-called "Bellamyites," who sought to remake the economy and society through the nationalization of industry. One of the last issues of ''The Nationalist'' noted that "over 500" had been formed. Owing to the growth of the Populist movement

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

and the financial and physical difficulties suffered by Bellamy, the Bellamyite Nationalist Clubs began to dissipate in 1892, lost their national magazine in 1894, and vanished from the scene entirely circa 1896.

Organizational history

Background

In 1888, a young

In 1888, a young Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

writer named Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

published a work of utopian fiction entitled Looking Backward, 2000-1887

'' telling the

Rip Van Winkle

"Rip Van Winkle" is a short story by the American author Washington Irving, first published in 1819. It follows a Dutch-American villager in colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who meets mysterious Dutchmen, imbibes their liquor and falls aslee ...

-like tale of a 19th-century New England capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

who awoke from a trace-slumber induced by hypnosis, to find a completely changed society in the far-distant year of 2000. In Bellamy's tale, a non-violent revolution had transformed the American economy and thereby society; private property had been abolished in favor of state ownership of capital and the elimination of social classes and the ills of society that he thought inevitably followed from them. In the new world of the year 2000, there was no longer war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

, poverty, crime

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

, prostitution, corruption, money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

, or taxes

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

. Neither did there exist such occupations seen by Bellamy as of dubious worth to society, such as politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking ...

s, lawyers, merchants, or soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

s.

Instead, Bellamy's utopian society of the future was based upon the voluntary employment of all citizens between the ages of 21 and 45, after which time all would retire

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one's active working life. A person may also semi-retire by reducing work hours or workload.

Many people choose to retire when they are elderly or incapable of doing their j ...

. Work was simple, aided by machine production, working hours short and vacation time long. The new economic basis of society effectively remade human nature

Human nature is a concept that denotes the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or ...

itself in Bellamy's idyllic vision, with greed, maliciousness, untruthfulness, and insanity all relegated to the past.

This vision of American possibilities came as a clarion call to many American intellectuals, and ''Looking Backward'' proved to be a massive best-seller of the day. Within a year, the book had sold some 200,000 copies and by the end of the 19th century, it had sold more copies than any other book published in America outside of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Moreover, a new political movement spontaneously emerged, dedicated to making Bellamy's utopian vision a practical reality — the so-called "Nationalist Movement," based upon the organization of local "Nationalist Clubs."

Origins (1888)

Preparation for the first Nationalist Club had begun early in the summer of 1888 with a letter fromCyrus Field Willard Cyrus Field Willard (August 17, 1858 – January 17, 1942) was an American journalist, political activist, and theosophist. Deeply influenced by the writing of Edward Bellamy, Willard is best remembered as a principal in several utopian socialist ...

, a labor reporter for the ''Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' who had been moved by Bellamy's vision of the future. Willard wrote directly to the author, asking for Bellamy's blessings for the establishment of "an association to spread the ideas in your book." Bellamy had responded to Willard's appeal positively, urging him in a July 4 letter:

Go ahead by all means and do it if you can find anyone to associate with. No doubt eventually the formation of such Nationalist Clubs or associations among our sympathizers all over the country will be a proper measure and it is fitting that Boston should lead off in this movement.No formal organization immediately followed based upon Willard's efforts, however, and it was not until early September that an entity known as the "Boston Bellamy Club" independently emerged, with Charles E. Bowers and

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

General Arthur F. Devereux playing the decisive organizing role. This group issued a public appeal on September 18, 1888, a short document which declared there to be "no higher, grander or more patriotic cause for men to enlist in than one for the elevation of their fellow man" and stated that "Edward Bellamy in his great work, ''Looking Backward,'' has pointed out the way by which the elevation of man can be attained."

In October 1888 Willard's small Nationalist circle joined forces with the Boston Bellamy Club, establishing "a permanent organization to further the Nationalization of industry." The first regular meeting of this remade organization, the "Nationalist Club" of Boston, was held on December 1, 1888, attended by 25 interested participants, with Charles E. Bowers elected chairman. A committee of 5 was established to create a plan for a permanent organization, including '' Boston Herald'' editorial writer Sylvester Baxter, Willard, Devereux, Bowers, and Christian socialist

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

clergyman W.D.P. Bliss. The third meeting of the Boston Nationalist Club, held on December 15, was attended by Bellamy himself, who predictably received a warm welcome.

Boston club members were overwhelmingly of the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

and included no small number of Theosophists

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion ...

— believers in spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

and reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is ...

and establishment of the brotherhood of humanity on earth — a popular philosophical trend of the day. Indeed, fully half of the members of the first Nationalist Club were members of the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century CE ...

, including key leaders Willard and Baxter.

The tone of the initial Nationalist movement was philanthropic

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

, intellectual, and elitist, with the Nationalist Clubs structured not as units of a political party — political action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes ...

was actually prohibited during the group's earliest days — but rather as chapters of an ethical movement. The Boston Nationalist Club held public lectures and from May 1889 published a monthly magazine called '' The Nationalist'', which attempted to spread Bellamy's ideas to a larger audience through the written word.

''The Nationalist'' was simultaneously the bulletin of the Theosophist-dominated Boston Nationalist Club and the official organ of the entire movement. The first editor was Henry Willard Austin

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

, a graduate of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

and attorney who was also a sometimes poet and Theosophist. The magazine never garnered a huge readership, peaking with a paid circulation of 9,000 subscribers, but it was influential in casting the first phase of the Nationalist movement as an ethical propaganda society dominated by the Boston club.

Expansion (1889–1890)

Even before the launch of its monthly magazine, the Nationalist Club of Boston found its emulators around the country. InNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

the New York Nationalist Club was launched on Sunday, April 7, 1889, in response to a call issued by recent Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

gubernatorial candidate J. Edward Hall. Although Hall proved too ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

to attend, a number of New York political activists immediately became active in the New York Nationalist Club, including SLP journalists Lucien Sanial

Lucien Delabarre Sanial (12 September 1835 – 7 January 1927) was a French-American newspaper editor, economist, and political activist. A pioneer member of the Socialist Labor Party of America, Sanial is best remembered as one of the earliest e ...

and Charles Sotheran as well as Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

lecturer Daniel DeLeon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician (Marxism), theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regar ...

. A group of about 100 members immediately emerged from the organizational gathering.

In Chicago the city's Nationalist Club was actually the continuation of an earlier organization known as the "Collectivist League," a group established on April 10, 1888, at a meeting attended by 20 people, including prominent New York socialist author Laurence Gronlund

Laurence Gronlund (, Available 1844–1899) was a Danish-born American lawyer, writer, lecturer, and political activist. Gronlund is best remembered for his pioneering work in adapting the International Socialism of Karl Marx and Ferdinand La ...

. President of the Chicago Club was a future top official of the Social Democratic Party of America, Jesse Cox, who notably delivered a lecture on the principles of state ownership of industry to a crowd of 1200 people gathered under the League's auspices at a Chicago theater. In February 1889 the Collectivist League changed its name to the Nationalist Club of Illinois and adopted a new declaration of principles, constitution, and by-laws modeled after those of the Boston Nationalist Club. By May 1889 membership in the Chicago Nationalist Club stood at about 50 and the group had begun with the publication of its own pamphlets

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

and the sponsorship of public lectures.

A Nationalist Club was launched in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

on January 31, 1889, and in Hartford, Connecticut on February 12, 1889. Other clubs sprouted up, in the words of Cyrus Field Willard, "here and there, as if by magic."

By 1891 it was reported that no fewer than 162 Nationalist Clubs were in existence. Other Nationalist Clubs were established abroad, including groups in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

The Bellamyite movement was a particularly potent in the state of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, which was home to 65 local Nationalist Clubs — about 40% of the organization's total — as well as 5 Nationalist periodicals. By way of contrast, the populous Eastern state of New York was home to just 16 Nationalist Clubs — and other states had fewer.

While the social composition of the Nationalist Clubs was generally dominated by urban professionals, including doctors, lawyers, teachers, journalists, and clergymen motivated by the social gospel, at times these groups drew the participation of an altogether different constituency, including active trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

ists affiliated with the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

or the American Federation of Labor. Among those participating were high-ranking AFL functionary P. J. McGuire in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

and radical activist Burnette G. Haskell in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

.

The various Nationalist Clubs were not centrally directed but instead possessed a certain amount of local autonomy and were linked together loosely through correspondence and co-sponsorship of touring lecturers.

Politicization (1890–1892)

First steps were taken into politics in the fall of 1890, with a Nationalist state ticket put forward in the state of

First steps were taken into politics in the fall of 1890, with a Nationalist state ticket put forward in the state of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

and at least one candidate running for office under the Nationalist banner in California. The possible emergency of a Nationalist Party was undercut by the birth of a new political organization in the field, however, with the People's Party ("Populists") immediately gaining the support of a broad segment of American farmers across the Midwest, South, and West. The violent Homestead Strike

The Homestead strike, also known as the Homestead steel strike, Homestead massacre, or Battle of Homestead, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security age ...

of 1892 also served as a catalyst for oppositional politics in the United States. These events served to politicize not only the Nationalist Clubs but Bellamy himself and he entered the political fray.

With ''The Nationalist'' magazine clearly headed for the financial rocks by the end of 1890, Edward Bellamy launched a new monthly magazine of his own in an effort to transform the Nationalist movement from a contemplative propaganda society into a hard-nosed political movement. This new publication was known as ''The New Nation

''New Nation'' was a weekly newspaper published in the UK for the Black British community. Launched in 1996, the newspaper was Britain's Number 1-selling black newspaper. The paper was published every Monday.

''New Nation'' was initially lau ...

,'' and it first rolled off the presses on January 31, 1891. Bellamy provided the finances for the new venture and sat as publisher and editor. Mason Green, a veteran journalist who was a graduate of Amherst College joined Bellamy as managing editor, with Henry R. Legate, organizer of the politically oriented Second Nationalist Club of Boston, aiding as assistant editor.

For the next three years the Nationalist movement's earlier largely hands-off approach to the dirty grind of daily politics was replaced by dedicated effort to achieve practical results through immediate political action. The logic of the situation made the upstart reform movement around the Nationalist Clubs the natural ally of the upstart movement emerging around the People's Party, and the two organizations intermingled. Nationalist Club members joined their local People's Party organizations en masse while Bellamy attempted to consolidate this alliance by molding his new publication into one of the most important voices of the Populist movement in the Eastern United States.

Bellamy and the active members of the Nationalist Clubs were strongly supportive of provisions of the People's Party platform which called for the nationalization of the nation's railroads and telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

system. The Nationalist Clubs remained primarily propaganda organizations even after Bellamy's entry into politics in 1891, although local clubs did occasionally nominate candidates after that date, although most commonly the Nationalists worked in tandem with the People's Party and its candidates.

The move of the Nationalist Clubs and their members from propaganda societies to political entities acting in alliance with the People's Party created a situation whereby the organizations fulfilled duplicate functions, to the detriment of the Bellamy organization. In the assessment of one historian:

By 1892 Populism had sapped the Nationalist movement of any real vigor it still had. The People's Party had a prospect for immediate success entirely lacking in Nationalism. Hundreds of Nationalists joined the Populists, leaving the clubs virtually hollow shells.

Decline (1893–1896)

Bellamy continued to work on behalf of the Nationalist movement through 1894, authoring a document entitled ''The Programme of the Nationalists'', which was published in the intellectual journal ''The Forum'' in March of that year. In this document, reprinted by the central publishing house of the Nationalist Clubs based in Philadelphia, Bellamy argued that

Bellamy continued to work on behalf of the Nationalist movement through 1894, authoring a document entitled ''The Programme of the Nationalists'', which was published in the intellectual journal ''The Forum'' in March of that year. In this document, reprinted by the central publishing house of the Nationalist Clubs based in Philadelphia, Bellamy argued that

Nationalism isOn February 3, 1894, Bellamy's ''The New Nation'' was forced to suspend publication owing to financial difficulties. The publication's top paid circulation in its best year had only reached the 8,000 mark, and even this had proven to be no more than a fond memory by 1894. New periodicals had emerged to pick up the slack, including ''The Coming Nation,'' a weekly newspaper published by Julius Augustus Wayland, which proclaimed itself to be an extension of the Bellamyite political tradition. Two years of phantom existence followed, with a handful of pamphlets produced by a Bureau of Nationalist Literature in Philadelphia on behalf of the rapidly waning movement. By 1896 the Bellamyite movement had expired, with all but a small handful of isolated groups vanished forever. With his health failing from the tuberculosis from which he had suffered since age 25, Bellamy turned once again to literary pursuits. In his last years Bellamy managed a sequel to ''Looking Backward,'' entitled ''Equality,'' which was published just prior to his premature death in 1898. In this final work, Bellamy turned his mind's eye to the question ofeconomic democracy Economic democracy is a socioeconomic philosophy that proposes to shift decision-making power from corporate managers and corporate shareholders to a larger group of public stakeholders that includes workers, customers, suppliers, neighbour .... It proposes to deliver society from the rule of the rich, and to establish economic equality by the application of the democratic formula to the production and distribution of wealth. It aims to put an end to the present irresponsible control of the economic interests of the country by capitalists pursuing their private ends, and to replace it by responsible public agencies acting for the general welfare.... As political democracy seeks to guarantee men against oppression exercised upon them by political forms, so the economic democracy of Nationalism would guarantee them against the more numerous and grievous oppressions exercised by economic methods.Bellamy, ''The Programme of the Nationalists,'' pg. 6.

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, dealing with the taboo subject of female reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:

Reproductive rights rest o ...

in a future, post-revolutionary America. Other subjects overlooked in ''Looking Backward,'' such as animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all Animal consciousness, sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their Utilitarianism, utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding s ...

and wilderness preservation, were dealt with in a similar context.

As such, ''Equality'' has been hailed by historian Franklin Rosemont as "one of the most forward-looking works of nineteenth-century radicalism," and was lauded in its own day by anarchist thinker Peter Kropotkin as "much superior" to ''Looking Backward'' for having analyzed "all the vices of the capitalistic system."

Criticism

Bellamy claimed he did not write ''Looking Backward'' with a view to creating a blueprint for political action. Asked in 1890 to describe the thought process behind creation of the novel, Bellamy emphasized that he had no particular sympathy with the extant socialist movement, but rather sought to write "a literary fantasy, a fairy tale of social felicity." Bellamy continued that he had "no thought of contriving a house which practical men might live in," but rather attempted to create "a cloud place for an ideal humanity" which was "out of reach of the sordid and material world of the present." Be that as it may, Bellamy's literary vision was the inspiration of the practical politics of the Nationalist Clubs and has drawnideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

criticism from some contemporary commentators. In the view of historian Arthur Lipow, in his book Bellamy consciously ignored positing democratic control in his idealized structure of the future, instead pinning his hopes upon bureaucratic

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

stratification

Stratification may refer to:

Mathematics

* Stratification (mathematics), any consistent assignment of numbers to predicate symbols

* Data stratification in statistics

Earth sciences

* Stable and unstable stratification

* Stratification, or st ...

and quasi-military organization of both economics and social relations. The modern military was seen by Bellamy as a prototype of future society in that it motivated organized and devoted activity in the national interest, Lipow argues With neither material need nor the pursuit of "wanton luxury" to impel action, it was to be this national interest which was seen as the chief motivating factor.

This was, in Lipow's view, a recipe for authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

:

If the workers and the vast majority were a brutish mass, there could be no question of forming a political movement out of them, nor of giving to them the task of creating a socialist society. The new institutions would not be created and shaped from below but would, of necessity, correspond to the plan laid down in advance by the utopian planner.As such, Lipow argues that Bellamy's vision was

technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which the decision-maker or makers are selected based on their expertise in a given area of responsibility, particularly with regard to scientific or technical knowledge. This system explicitly contrasts wi ...

in nature, based upon the mandates of an expert elite rather than individual liberty and freely-decided action.

An early Marxist critique of Bellamyism was supplied by Morris Hillquit

Morris Hillquit (August 1, 1869 – October 8, 1933) was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America and prominent labor lawyer in New York City's Lower East Side. Together with Eugene V. Debs and Congressman Victor L. Berger, Hil ...

, a historian of American socialism

The history of the socialist movement in the United States spans a variety of tendencies, including Anarchism in the United States, anarchists, Communism in the United States, communists, democratic socialists, Marxists, Marxist–Leninists, T ...

and leader in the Socialist Party of America, who noted in 1903:

Bellamy was not familiar with the modern socialist philosophy when he wrote his book. His views and theories were the result of his own observations and reasoning, and, like all other utopians, he evolved a complete social scheme hinging mainly on one fixed idea. In his case it was the idea 'of an industrial army for ''maintaining'' the community, precisely as the duty of ''protecting'' it is entrusted to a military army'..."

"The historical development of society and the theory of the class struggle, which play so great a part in the philosophy of modern socialism, have no place in Bellamy's system. With him it is all a question of expediency; he is not an exponent of the laws of social development, but a social inventor.

See also

*Georgism

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—includi ...

Footnotes

Sources

* * Reprinted in 2015: * * * * * *Publications

Official magazines

* ''The Nationalist'' (1889–1891) *Vol. 1 (1889)

Vol. 2 (1890)

Vol. 3 (1891)

* ''The New Nation'' (1891–1894) ** Vol. 1 (1891) , Vol. 2 (1892)

Vol. 3 (1893)

, Vol. 4 (1894)

Books by Edward Bellamy

''Looking Backward, 2000-1887.''

Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1889.

''Equality.''

New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1898.

Other magazines and pamphlets

''Looking Forward,''

vol. 1, no. 2 (September 1889), National City, California.

''Principles and Purposes of Nationalism: Edward Bellamy's Address at Tremont Temple, Boston, on the Nationalist Club's First Anniversary, December 19, 1889.''

Philadelphia: Bureau of Nationalist Literature, n.d. * Edward Bellamy

''The Programme of the Nationalists.''

Philadelphia: Bureau of Nationalist Literature, 1894. —First published in ''The Forum,'' March 1894.

Anti-Nationalist publications

* George A. Sanders''Reality; or, Law and Order vs. Anarchy and Socialism: A Reply to Edward Bellamy's Looking backward and Equality.''

Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1898.

Further reading

* Sylvia E. Bowman, ''Edward Bellamy Abroad: An American Propher's Influence.'' New York: Twayne Publishers, 1962. * Sylvia E. Bowman, ''The Year 2000: A Critical Biography Of Edward Bellamy.'' New York: Bookman Associates, 1958. * Laurence Gronlund"Nationalism,"

''The Arena,'' vol. 1, whole no. 2 (January 1890), pp. 153–165. * James J. Kopp, "Looking Backward at Edward Bellamy's Influence in Oregon, 1888-1936," ''Oregon Historical Quarterly,'' vol. 104, no. 1 (Spring 2003). * Everett W. MacNair, ''Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist Movement, 1889 to 1894: A Research Study of Edward Bellamy's Work as a Social Reformer.'' Milwaukee, WI: Fitzgerald Co., 1957. * Daphne Patai (ed.), ''Looking Backward, 1988-1888: Essays on Edward Bellamy.'' Amherst, MA:

University of Massachusetts Press

The University of Massachusetts Press is a university press that is part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst, UMass) is a public research university in Amherst, Massachusetts a ...

, 1988.

* Howard Quint, ''The Bellamy Nationalist Movement: 1888-1894.'' Ph.D. dissertation. Stanford University, 1942.

* John Thomas, ''Alternative America: Henry George, Edward Bellamy, Henry Demarest Lloyd and the Adversary Tradition.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.

* Richard Toby Widdicombe, ''Edward Bellamy: An Annotated Bibliography of Secondary Criticism.'' New York: Garland Publishing, 1988.

* William Frank Zornow, "Bellamy Nationalism in Ohio, 1891 to 1896," ''Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, v. 58, no. 2 (1949).

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nationalist Clubs

1888 establishments in the United States

1896 disestablishments

Bellamyism

Economic ideologies

Nationalist organizations

Organizations established in 1888

Populism

Socialism