National Underground Railroad Freedom Center on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is a

After ten years of planning, fundraising, and construction, the $110 million Freedom Center opened to the public on August 3, 2004; official opening ceremonies took place on August 23. The 158,000 square foot (15,000 m²) structure was designed by

After ten years of planning, fundraising, and construction, the $110 million Freedom Center opened to the public on August 3, 2004; official opening ceremonies took place on August 23. The 158,000 square foot (15,000 m²) structure was designed by

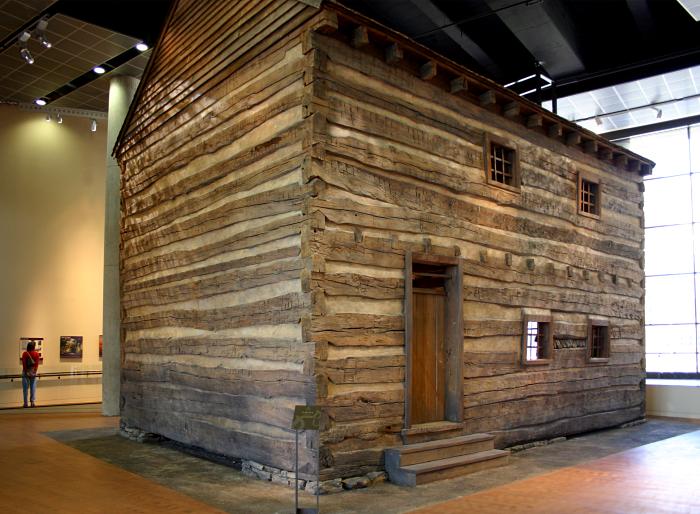

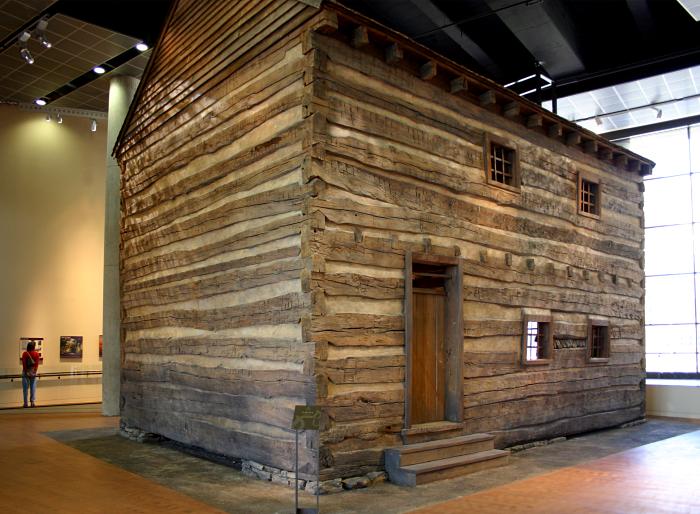

The center's principal artifact is a 21 by 30-foot (6 by 9 m), two-story log slave pen built in 1830. By 2003, it was "the only known surviving rural slave jail," previously used to house slaves prior to their being shipped to auction.PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN, "In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past"

The center's principal artifact is a 21 by 30-foot (6 by 9 m), two-story log slave pen built in 1830. By 2003, it was "the only known surviving rural slave jail," previously used to house slaves prior to their being shipped to auction.PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN, "In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past"

''New York Times'', 6 May 2003 The structure was moved from a farm in The pen was originally owned by Captain John Anderson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and slave trader. Slaves from the area were transported from Dover, Kentucky to slave markets in

The pen was originally owned by Captain John Anderson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and slave trader. Slaves from the area were transported from Dover, Kentucky to slave markets in

"Slave pen now holds history"

''The

"Freedom Center's Future"

''The Cincinnati Enquirer''

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center site

NURFC sponsored project: Passage to Freedom – Underground Railroad sites in the State of Ohio

{{authority control History museums in Ohio African-American museums in Ohio 2004 establishments in Ohio Museums in Cincinnati Underground Railroad Museums established in 2004 African-American history in Cincinnati

museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make th ...

in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

, based on the history of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. Opened in 2004, the Center also pays tribute to all efforts to "abolish human enslavement and secure freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving one ...

for all people."

It is one of a new group of "museums of conscience" in the United States, along with the Museum of Tolerance

The Museum of Tolerance-Beit HaShoah (MOT, House of the Holocaust), a multimedia museum in Los Angeles, California, United States, is designed to examine racism and prejudice around the world with a strong focus on the history of the Holocaust. T ...

, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust. Adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the USHMM provides for the documentation, study, and interpretation of Holocaust h ...

and the National Civil Rights Museum

The National Civil Rights Museum is a complex of museums and historic buildings in Memphis, Tennessee; its exhibits trace the history of the civil rights movement in the United States from the 17th century to the present. The museum is built aro ...

. The Center offers insight into the struggle for freedom in the past, in the present, and for the future, as it attempts to challenge visitors to contemplate the meaning of freedom in their own lives. Its location recognizes the significant role of Cincinnati in the history of the Underground Railroad, as thousands of slaves escaped to freedom by crossing the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

from the southern slave states. Many found refuge in the city, some staying there temporarily before heading north to gain freedom in Canada.

The structure

After ten years of planning, fundraising, and construction, the $110 million Freedom Center opened to the public on August 3, 2004; official opening ceremonies took place on August 23. The 158,000 square foot (15,000 m²) structure was designed by

After ten years of planning, fundraising, and construction, the $110 million Freedom Center opened to the public on August 3, 2004; official opening ceremonies took place on August 23. The 158,000 square foot (15,000 m²) structure was designed by Boora Architects

Bora Architects is an architectural firm based in Portland, Oregon.

History

The company's former name, Boora Architects, was derived from the names of now-retired foundational partners Broome, Oringdulph, O'Toole, Rudolf, and Associates. In 2 ...

(design architect) of Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

with Blackburn Architects (architect of record) of Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

. Three pavilions celebrate courage

Courage (also called bravery or valor) is the choice and willingness to confront agony, pain, danger, uncertainty, or intimidation. Valor is courage or bravery, especially in battle.

Physical courage is bravery in the face of physical pain, ...

, cooperation

Cooperation (written as co-operation in British English) is the process of groups of organisms working or acting together for common, mutual, or some underlying benefit, as opposed to working in competition for selfish benefit. Many animal a ...

and perseverance. The exterior features rough travertine

Travertine ( ) is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and even rusty varieties. It is formed by a p ...

stone from Tivoli, Italy

Tivoli ( , ; la, Tibur) is a town and in Lazio, central Italy, north-east of Rome, at the falls of the Aniene river where it issues from the Sabine hills. The city offers a wide view over the Roman Campagna.

History

Gaius Julius Solinu ...

on the east and west faces of the building, and copper panels on the north and south. According to Walter Blackburn

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

, one of its primary architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

s before his death, the building's "undulating quality" expresses the fields and the river that escaping slaves crossed to reach freedom. First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non- monarchical head of state or chief executive. The term is also used to describe a woman seen to be at the ...

Laura Bush

Laura Lane Welch Bush (''née'' Welch; born November 4, 1946) is an American teacher, librarian, memoirist and author who was First Lady of the United States from 2001 to 2009. Bush previously served as First Lady of Texas from 1995 to 2000. ...

, Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Gail Winfrey (; born Orpah Gail Winfrey; January 29, 1954), or simply Oprah, is an American talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and philanthropist. She is best known for her talk show, ''The Oprah Winfrey Show'', b ...

, and Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

attended the groundbreaking ceremony on June 17, 2002.

Slave pen

The center's principal artifact is a 21 by 30-foot (6 by 9 m), two-story log slave pen built in 1830. By 2003, it was "the only known surviving rural slave jail," previously used to house slaves prior to their being shipped to auction.PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN, "In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past"

The center's principal artifact is a 21 by 30-foot (6 by 9 m), two-story log slave pen built in 1830. By 2003, it was "the only known surviving rural slave jail," previously used to house slaves prior to their being shipped to auction.PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN, "In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past"''New York Times'', 6 May 2003 The structure was moved from a farm in

Mason County, Kentucky

Mason County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat is Maysville. The county was created from Bourbon County, Virginia in 1788 and named for George Mason, a Virginia delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention ...

, where a tobacco barn had been built around it.

It was reconstructed in the second-floor atrium of the museum, where visitors encounter it again and again while exploring other exhibits. Passersby on the street outside can also see it through the Center's large windows.

The pen was originally owned by Captain John Anderson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and slave trader. Slaves from the area were transported from Dover, Kentucky to slave markets in

The pen was originally owned by Captain John Anderson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and slave trader. Slaves from the area were transported from Dover, Kentucky to slave markets in Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the county seat of and only city in Adams County, Mississippi, United States. Natchez has a total population of 14,520 (as of the 2020 census). Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, ...

and ; they were held in this pen for a few days or several months, as he and other traders waited for favorable market conditions and higher selling prices. The pen has eight small windows, the original stone floor and fireplace. On the second floor are a row of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

rings (see photo at right) through which a central chain ran, tethering men on either side. Male slaves were held on the second floor, while women were kept on the first floor, where they used the fireplace for cooking.

"The pen is powerful," saysVisitors to the museum can walk through the holding pen and touch its walls. The first names of some of the slaves believed to have been held in the pen are listed on a wooden slab in the pen's interior; they were documented in records kept by slave traders who used the pen. Westmoreland spent three and a half years uncovering the story of the slave jail. Its authentication by him and other historians is considered "a landmark in the material culture of slavery." Westmoreland said,Carl Westmoreland Carl B. Westmoreland (March 8, 1937 – March 10, 2022) was an American community organizer, preservationist, and senior historian at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. In 1967, he was one of the founding members of the Mount Auburn ...,curator A curator (from la, cura, meaning "to take care") is a manager or overseer. When working with cultural organizations, a curator is typically a "collections curator" or an "exhibitions curator", and has multifaceted tasks dependent on the parti ...and senior adviser to the museum. "It has the feeling of hallowed ground. When people stand inside, they speak in whispers. It is a sacred place. I believe it is here to tell a story – the story of the internal slave trade to future generations."

We're just beginning to remember. There is a hidden history right below the surface, part of the unspoken vocabulary of the American historic landscape. It's nothing but a pile of logs, yet it is everything.

Other features

Prominent features of the Center include: * The ''"Suite for Freedom"'' Theater features three animated films: these address the fragile nature of freedom throughout human history, particularly as related to the Underground Railroad and slavery in theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

* The ''"ESCAPE! Freedom Seekers"'' interactive display about the Underground Railroad; it presents school groups and families with young children a series of choices on an imaginary escape attempt. The gallery features information about figures including William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

, a leading abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

; Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 slaves, including family and friends, u ...

, an escaped slave and "conductor" on the Underground Railroad; and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, an escaped slave who became an abolitionist and powerful orator.

* The film, ''Brothers of the Borderland,'' tells the story of the Underground Railroad in Ripley, Ohio

Ripley is a village in Union Township, Brown County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River 50 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The population was 1,750 at the 2010 census.

History

Colonel James Poage, a veteran of the American Revolution, ar ...

, where conductors, both black ( John Parker) and white ( Reverend John Rankin), helped slaves such as a fictional Alice. It was directed by Julie Dash

Julie Ethel Dash (born October 22, 1952) is an American film director, writer and producer. Dash received her MFA in 1985 at the UCLA Film School and is one of the graduates and filmmakers known as the L.A. Rebellion. The L.A. Rebellion refers ...

.

* Exhibits about the history of slavery and opponents including John Brown and President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

; and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

that ended it.

* ''The Struggle Continues,'' an exhibit portrays continuing challenges faced by African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

since the end of slavery, struggles for freedom in today's world, and ways that the Underground Railroad has inspired groups in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

.

* The ''John Parker Library'' houses a collection of multimedia materials about the Underground Railroad and freedom-related issues.

* The ''FamilySearch Center'' allows visitors to investigate their own roots.

*Jane Burch Cochran

Jane Burch Cochran is a fabric artist who is known for her work that combines traditional American quiltmaking with painting and fabric embellishments. She received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship for quiltmaking in 1993.

She is als ...

created a quilt, "Crossing to Freedom," a 7 ft by 10 ft that depicts symbolic images from the anti-slavery era to the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

that hangs at an entrance to the center.

The Freedom Center's former Executive Director and CEO

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a central executive officer (CEO), chief administrator officer (CAO) or just chief executive (CE), is one of a number of corporate executives charged with the management of an organization especially ...

, John Pepper, was previously the CEO of Procter & Gamble.

See also

*List of museums focused on African Americans

This is a list of museums in the United States whose primary focus is on African American culture and history. Such museums are commonly known as African American museums. According to scholar Raymond Doswell, an African American museum is "an ...

References

* Bauer, Marilyn (February 8, 2004)"Slave pen now holds history"

''The

Cincinnati Enquirer

''The Cincinnati Enquirer'' is a morning daily newspaper published by Gannett in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. First published in 1841, the ''Enquirer'' is the last remaining daily newspaper in Greater Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, alt ...

.''

* Brown, Patricia Leigh (May 6, 2003). "In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past", ''The New York Times''

*Brown, Jessica (June 13, 2008)"Freedom Center's Future"

''The Cincinnati Enquirer''

External links

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center site

NURFC sponsored project: Passage to Freedom – Underground Railroad sites in the State of Ohio

{{authority control History museums in Ohio African-American museums in Ohio 2004 establishments in Ohio Museums in Cincinnati Underground Railroad Museums established in 2004 African-American history in Cincinnati