Nathaniel Banks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from

In 1848, Banks was victorious in another run for the state legislature, successfully organizing elements in Waltham whose votes were not easily controlled by the Whig-controlled Boston Manufacturing Company. Company leaders could effectively compel their workers to vote for Whig candidates because there was no

In 1848, Banks was victorious in another run for the state legislature, successfully organizing elements in Waltham whose votes were not easily controlled by the Whig-controlled Boston Manufacturing Company. Company leaders could effectively compel their workers to vote for Whig candidates because there was no

As the Civil War became imminent in early 1861,

As the Civil War became imminent in early 1861,

Banks's division technically belonged to

Banks's division technically belonged to

In July, Maj. Gen John Pope was placed in command of the newly-formed

In July, Maj. Gen John Pope was placed in command of the newly-formed

In November 1862, President Lincoln gave Banks command of the

In November 1862, President Lincoln gave Banks command of the

Under political pressure to show progress, Banks embarked on operations to secure a route that bypassed Port Hudson via the Red River in late March. He was eventually able to reach

Under political pressure to show progress, Banks embarked on operations to secure a route that bypassed Port Hudson via the Red River in late March. He was eventually able to reach

Fort Banks in

Fort Banks in

Volume 1Volume 2

* * * * * * * * *

Website of Banks links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Banks, Nathaniel Prentice 1816 births 1894 deaths Politicians from Waltham, Massachusetts Massachusetts Liberal Republicans Speakers of the United States House of Representatives Governors of Massachusetts Speakers of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Democratic Party members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Massachusetts state senators Union Army generals United States Marshals 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American railroad executives People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives Know-Nothing members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Independent members of the United States House of Representatives Massachusetts Independents Republican Party governors of Massachusetts American male journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American politicians American abolitionists American suffragists

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and a Union general during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, and his oratorical skills were noted by the Democratic Party. However, his abolitionist views fitted him better for the nascent Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

, through which he became Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The speaker of the United States House of Representatives, commonly known as the speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives. The office was established in 1789 by Article I, Section 2 of the ...

and Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the chief executive officer of the government of Massachusetts. The governor is the head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

Massachuset ...

in the 1850s. Always a political chameleon (for which he was criticized by contemporaries), Banks was the first professional politician (with no outside business or other interests) to serve as Massachusetts Governor.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

appointed Banks as one of the first political major generals

A political general is a general officer or other military leader without significant military experience who is given a high position in command for political reasons, through political connections, or to appease certain political blocs and fact ...

, over the heads of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

regulars, who initially resented him, but came to acknowledge his influence on the administration of the war. After suffering a series of inglorious setbacks in the Shenandoah River

The Shenandoah River is the principal tributary of the Potomac River, long with two forks approximately long each,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 in t ...

Valley at the hands of Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, Banks replaced Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

at as commander of the Department of the Gulf

The Department of the Gulf was a command of the United States Army in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

History United States Army (Civil War)

Creation

The department was con ...

, charged with the administration of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

and gaining control of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. He failed to reinforce Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

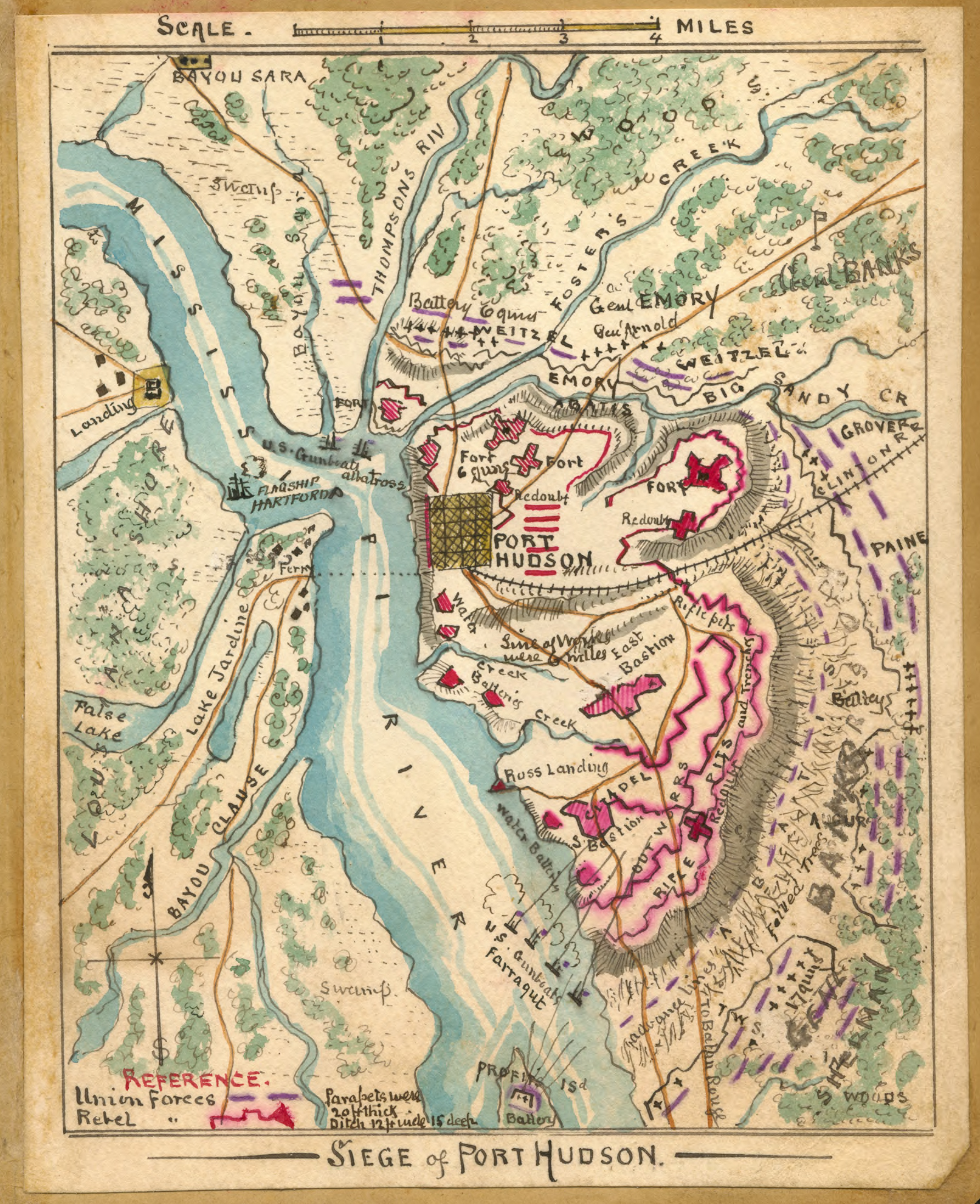

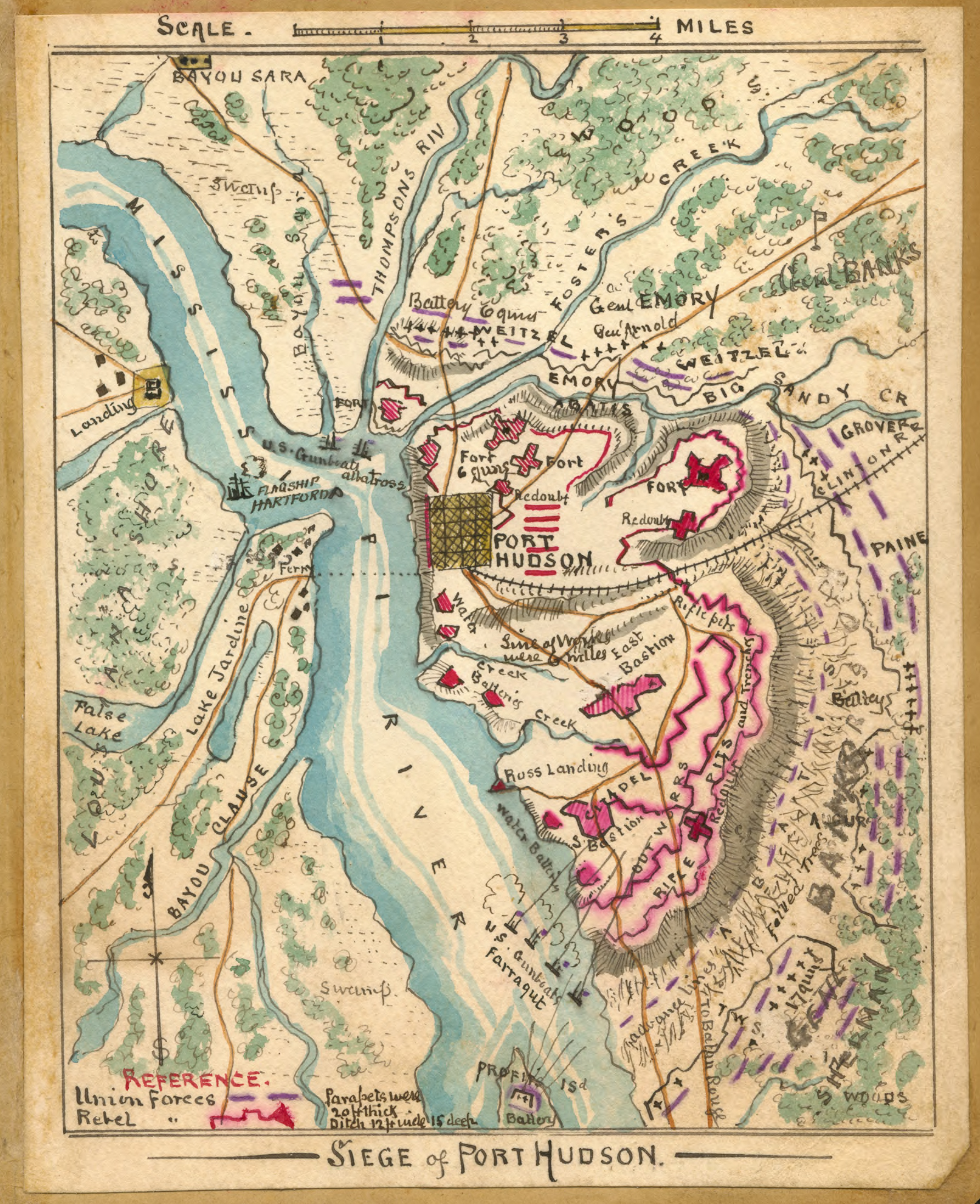

at Vicksburg, and badly handled the Siege of Port Hudson

The siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, (May 22 – July 9, 1863) was the final engagement in the Union campaign to recapture the Mississippi River in the American Civil War.

While Union General Ulysses Grant was besieging Vicksburg upriver, Ge ...

, taking its surrender only after Vicksburg had fallen. He then launched the Red River Campaign, a failed attempt to occupy northern Louisiana and eastern Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

that prompted his recall. Banks was regularly criticized for the failures of his campaigns, notably in tactically important tasks, including reconnaissance. Banks was also instrumental in early reconstruction efforts in Louisiana, intended by Lincoln as a model for later such activities.

After the war, Banks returned to the Massachusetts political scene, serving in Congress, where he supported Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

, influenced the Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

legislation, and supported women's suffrage. In his later years, he adopted more liberal progressive causes, and served as a United States marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforcem ...

for Massachusetts before suffering a decline in his mental faculties.

Early life

Nathaniel Prentice Banks was born atWaltham, Massachusetts

Waltham ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, and was an early center for the labor movement as well as a major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. The original home of the Boston Manufacturing Company, ...

, the first child of Nathaniel P. Banks Sr. and Rebecca Greenwood Banks, on January 30, 1816. His father worked in the textile mill

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

of the Boston Manufacturing Company

The Boston Manufacturing Company was a business that operated one of the first factories in America. It was organized in 1813 by Francis Cabot Lowell, a wealthy Boston merchant, in partnership with a group of investors later known as The Boston ...

, eventually becoming a foreman. Banks went to local schools until the age of fourteen, at which point the family's financial demands compelled him to take a mill job. He started as a bobbin boy

A bobbin boy was a boy who worked in a textile mill in the 18th and early 19th centuries. One example of rising from this job to great heights in America was young Andrew Carnegie, who at age 13 worked as a bobbin boy in 1848.

Description

In th ...

, responsible for replacing bobbin

A bobbin or spool is a spindle or cylinder, with or without flanges, on which yarn, thread, wire, tape or film is wound. Bobbins are typically found in industrial textile machinery, as well as in sewing machines, fishing reels, tape measu ...

s full of thread with empty ones, working in the mills of Waltham and Lowell. Because of this role he became known as Bobbin Boy Banks, a nickname he carried throughout his life. He was at one time apprenticed as a mechanic alongside Elias Howe, a cousin who later had the first patent for a sewing machine with a lockstitch design.

Recognizing the value of education, Banks continued to read, sometimes walking to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

on his days off to visit the Atheneum Library. He attended company-sponsored lectures by luminaries of the day including Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

and other orators. He formed a debate club with other mill workers to improve their oratorical skills, and took up acting. He became involved in the local temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

; speaking at its events brought him to the attention of Democratic Party leaders, who asked him to speak at campaign events during the 1840 elections. He honed his oratorical and political skills by emulating Robert Rantoul Jr., a Democratic Congressman who also had humble beginnings. His personal good looks, voice, and flair for presentation were all assets that he used to gain advantage in the political sphere, and he deliberately sought to present himself with a more aristocratic bearing than was suggested by his humble beginnings.

Banks's success as a speaker convinced him to quit the mill. He first worked as an editor for two short-lived political newspapers; after they failed he ran for a seat in the state legislature in 1844, but lost. He then applied for a job to Rantoul, who had been appointed Collector of the Port of Boston

The Port of Boston ( AMS Seaport Code: 0401, UN/LOCODE: US BOS) is a major seaport located in Boston Harbor and adjacent to the City of Boston. It is the largest port in Massachusetts and one of the principal ports on the East Coast of the Unite ...

, a patronage position. Banks's job, which he held until political changes forced him out in 1849, gave him sufficient security that he was able to marry Mary Theodosia Palmer, an ex-factory employee he had been courting for some time. Banks again ran for the state legislature in 1847, but was unsuccessful.

Antebellum political career

In 1848, Banks was victorious in another run for the state legislature, successfully organizing elements in Waltham whose votes were not easily controlled by the Whig-controlled Boston Manufacturing Company. Company leaders could effectively compel their workers to vote for Whig candidates because there was no

In 1848, Banks was victorious in another run for the state legislature, successfully organizing elements in Waltham whose votes were not easily controlled by the Whig-controlled Boston Manufacturing Company. Company leaders could effectively compel their workers to vote for Whig candidates because there was no secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vo ...

. He was at first moderate in opposition to the expansion of slavery, but recognizing the potency of the burgeoning abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movement, he became more strongly attached to that cause as a vehicle for political advancement. This brought Banks, along with fellow Democrats Rantoul and George S. Boutwell to form a coalition with the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

that successfully gained control of the legislature and governor's chair. The deals negotiated after the coalition win in the 1850 election put Boutwell in the governor's chair and made Banks the Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

This is a list of speakers of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. The Speaker of the House presides over the House of Representatives. The Speaker is elected by the majority party caucus followed by confirmation of the full House through ...

. Although Banks did not like the radical Free Soiler Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

(either personally or for his strongly abolitionist politics), he supported the coalition agreement that resulted in Sumner's election to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

, despite opposition from conservative Democrats. His role as house speaker and his effectiveness in conducting business raised his status significantly, as did his publicity work for the state Board of Education.

Congress

In 1852, Banks sought the Democratic nomination for a seat in theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

. While it was at first granted, his refusal to disavow abolitionist positions meant support was withdrawn by party conservatives. He ended up winning a narrow victory anyway, with Free Soil support. In 1853, he presided over the state Constitutional Convention of 1853. This convention produced a series of proposals for constitutional reform, including a new constitution, all of which were rejected by voters. The failure, which was led by Whigs and conservative anti-abolitionist Democrats, spelled the end of the Democratic-Free Soil coalition.

In Congress, Banks sat on the Committee of Military Affairs. He bucked the Democratic party line by voting against the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

, which overturned the 1820 Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

, using his parliamentary skills in an effort to keep the bill from coming to a vote. Supported by his constituents, he then publicly endorsed the abolitionist cause. His opposition came despite long stated support for Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

(the idea that the United States was destined to rule the North American continent

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

), which the bill's proponents claimed it furthered. In 1854, he formally joined the so called Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

cause, a secretive populist and anti-immigration nativist movement – officially named American Party since 1855. He was renominated for Congress by the Democrats and Free Soilers, and won an easy victory in that year's Know Nothing landslide victory. Banks was, along with Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

and Governor Henry J. Gardner, considered one of the political leaders of the Know Nothing movement, although none of the three supported its extreme anti-immigrant positions of many of its supporters.

In 1855, Banks agreed to chair the convention of a new Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

convention, whose platform was intended to bring together antislavery interests from the Democrats, Whigs, Free Soilers, and Know Nothings. When Know Nothing Governor Henry Gardner refused to join in the fusion, Banks carefully kept his options open, passively supporting the Republican effort but also avoiding criticism of Gardner in his speeches. Gardner was reelected. During the summer of 1855, Banks was invited to speak at an antislavery rally in Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

, his first major speaking opportunity outside Massachusetts. In the speech, Banks expressed his opinion that the Union did not necessarily need to be preserved, say that under certain conditions it would be appropriate to "let he Unionslide". Future political opponents would repeatedly use these words against him, accusing him of "disunionism".

At the opening of the 34th U.S. Congress in December 1855, after the Democrats had lost their majority and only made up 35% of the House, representatives from several parties opposed to slavery's spread gradually united in supporting the Know Nothing Banks for Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. After the longest and one of the most bitter speakership contests on record, lasting from December 3, 1855, to February 2, 1856, Banks was chosen on the 133rd ballot. The coalition supporting him was formed by his American Party (known as the Know Nothing Party) and the Opposition Party, which opposed the Democrats, marking the first form of a coalition in congressional history. This victory was lauded at the time as the "first Republican victory" and "first Northern victory" – although Banks is officially affiliated as Speaker from the American Party – and greatly raised Banks' national profile. He gave antislavery men important posts in Congress for the first time, and cooperated with investigations of both the Kansas conflict and the caning of Charles Sumner

The Caning of Charles Sumner, or the Brooks–Sumner Affair, occurred on May 22, 1856, in the United States Senate chamber, when Representative Preston Brooks, a pro-slavery Democrat from South Carolina, used a walking cane to attack Senator Cha ...

on the floor of the Senate. Because of his fairness in dealing with the numerous factions, as well his parliamentary ability, Banks was lauded by others in the body, including former Speaker Howell Cobb, who called him "in all respects the best presiding officer had ever seen."

Banks played a key role in 1856 in bringing forward John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

as a moderate Republican presidential nominee. Because of his success as speaker, Banks was considered a possible presidential contender, and his name was put in nomination by supporters (knowing that he supported Frémont) at the Know Nothing convention, held one week before the Republicans met. Banks then refused the Know Nothing nomination, which went instead to former President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

. Banks was active on the stump in support of Frémont, who lost the election to James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

. Banks easily won reelection to his own seat, though Democrats regained control of the House of Representatives. He was not re-nominated for speaker when the 35th Congress convened in December 1857.

Governor of Massachusetts

In 1857, Banks ran forGovernor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the chief executive officer of the government of Massachusetts. The governor is the head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

Massachuset ...

against the incumbent Gardner. His nomination by the Republicans was contentious, with opposition coming primarily from radical abolitionist interests opposed to his comparatively moderate stand on the issue. After a contentious general election campaign Banks won a comfortable victory. One key action Banks took in support of the antislavery movement was the dismissal of Judge Edward G. Loring

Edward Greely Loring (January 28, 1802 – June 18, 1890) was a Judge of Probate in Massachusetts, a United States Commissioner of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts and a judge of the Court of Claims. He was revil ...

.Voss-Hubbard (1995), pp. 173–174 Loring had ruled in 1854 that Anthony Burns

Anthony Burns (May 31, 1834 – July 17, 1862) was an African-American man who escaped from slavery in Virginia in 1854. His capture and trial in Boston, and transport back to Virginia, generated wide-scale public outrage in the North and ...

, a fugitive slave, be returned to slavery under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most cont ...

. Under the pressure of a public petition campaign spearheaded by William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

, the legislature passed two Bills of Address, in 1855 and 1856, calling for Loring's removal from his state office, but in both cases Gardner had declined to remove him. Banks signed a third such bill in 1858. He was rewarded with significant antislavery support, easily winning reelection in 1858.

Banks's 1859 reelection was influenced by two significant issues. One was a state constitutional amendment requiring newly naturalized citizens to wait two years before becoming eligible to vote. Promoted by the state's Know Nothings, it was passed by referendum in May of that year. Banks, catering to Know Nothing supporters, supported its passage, although Republicans elsewhere opposed such measures, because they were seeking immigrant votes.Hollandsworth, pp. 37–38 The amendment was repealed in 1863.Baum, p. 48 The other issue was John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, which more radical Republicans (notably John Albion Andrew

John Albion Andrew (May 31, 1818 – October 30, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. He was elected in 1860 as the 25th Governor of Massachusetts, serving between 1861 and 1866, and led the state's contributions to ...

) supported. Not yet ready for armed conflict, the state voted for the more moderate Banks. After the election, Banks vetoed a series of bills, over provisions removing a restriction limiting state militia participation to whites. This incensed the radical abolitionist forces in the legislature, but they were unable to override his vetoes in that year's session, or of similar bills passed in the next.

Banks made a serious bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, but dislike of him by the radicals in the state party harmed him. His failure to secure a majority in the state delegation prompted him to skip the national convention, where he received first-ballot votes as a nominee for Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

. His attempt to promote Henry L. Dawes

Henry Laurens Dawes (October 30, 1816February 5, 1903) was an attorney and politician, a Republican United States Senator and United States Representative from Massachusetts. He is notable for the Dawes Act (1887), which was intended to stimul ...

, another moderate Republican, as his successor in the governor's chair also failed: the party nominated the radical Andrew, who went on to win the general election. Banks's farewell speech, given with civil war looming, was an appeal for moderation and union.Harrington, p. 52

During the summer of 1860, Banks accepted an offer to become a resident director of the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line al ...

, which had previously employed his mentor Robert Rantoul. Banks moved to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

after leaving office, and was engaged primarily in the promotion and sale of the railroad's extensive lands. He continued to speak out in Illinois against the breakup of the Union.

Civil War

As the Civil War became imminent in early 1861,

As the Civil War became imminent in early 1861, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

considered Banks for a cabinet post, despite a negative recommendation from Governor Andrew, who considered Banks to be unsuitable for any office.Baum, p. 57 Lincoln rejected Banks in part because he had accepted the railroad job, but chose him as one of the first major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

s (Maj. Gen.) of volunteers

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

, appointing him on May 16, 1861. Many of the professional soldiers in the regular army were unhappy with this but Banks, given his national prominence as a leading Republican, brought political benefits to the administration, including the ability to attract recruits and money for the Union cause, despite his lack of field experience.

First command

Banks first commanded a military district in eastern Maryland, which notably includedBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, a hotbed of secessionist sentiment and a vital rail link. Banks for the most part stayed out of civil affairs, allowing political expression of secessionism to continue, while maintaining important rail connections between the north and Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morg ...

. He did, however arrest the police chief and commissioners of the city of Baltimore, and replaced the police force with one that had more carefully vetted pro-Union sympathies. In August 1861, Banks was assigned to the western district of Maryland. There he was responsible for the arrest of legislators sympathetic to the Confederate cause (as was John Adams Dix

John Adams Dix (July 24, 1798 – April 21, 1879) was an American politician and military officer who was Secretary of the Treasury, Governor of New York and Union major general during the Civil War. He was notable for arresting the pro-Souther ...

, who succeeded Banks in the eastern district) in advance of legislative elections. This, combined with the release of local soldiers in his army to vote, ensured that the Maryland legislature remained pro-Union. Banks's actions had a chilling effect on Confederate sentiment in Maryland. Although it was a slave state, it remained loyal through the war.Harris, pp. 66–80

Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Banks's division technically belonged to

Banks's division technically belonged to George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

despite serving as an independent command in the Shenandoah Valley. On March 14, 1862, President Lincoln issued an executive order forming all troops in McClellan's department into corps. Banks thus became a corps commander, in charge of his own former division, now commanded by Brig. Gen Alpheus Williams, and the division of Brig. Gen James Shields, which was added to Banks's command. After Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

was turned back at the First Battle of Kernstown

The First Battle of Kernstown was fought on March 23, 1862, in Frederick County and Winchester, Virginia, the opening battle of Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American ...

on March 23, Banks was instead ordered to pursue Jackson up the valley, to prevent him from reinforcing the defenses of Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

. When Banks's men reached the southern Valley at the end of a difficult supply line, the president recalled them to Strasburg, at the northern end. Jackson then marched rapidly down the adjacent Luray Valley, and encountered some of Banks' forces in the Battle of Front Royal

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought on May 23, 1862, during the American Civil War, as part of Jackson's Valley campaign. Confederate forces commanded by Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson w ...

on May 23. This prompted Banks to withdraw to Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, where Jackson again attacked on May 25. The Union forces were poorly arrayed in defense, and retreated in disorder across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

and back into Maryland. An attempt to capture Jackson's forces in a pincer movement (with forces led by John Frémont

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

) failed, and Jackson was able to reinforce Richmond. Banks was criticized for mishandling his troops and performing inadequate reconnaissance in the campaign, while his political allies sought to pin the blame for the debacle on the War Department.

Northern Virginia Campaign

In July, Maj. Gen John Pope was placed in command of the newly-formed

In July, Maj. Gen John Pope was placed in command of the newly-formed Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

, which consisted of the commands of Banks, Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

, and Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

. By early August this force was in Culpeper County

Culpeper County is a county located along the borderlands of the northern and central region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 52,552. Its county seat and only incorporated community is C ...

. Pope gave Banks an ambiguous series of orders, directing him south of Culpeper to determine enemy strength, hold a fortified defensive position, and to engage the enemy. Banks showed none of the caution he had displayed against Stonewall Jackson in the Valley campaign, and moved to meet a larger force. Confederates he faced were numerically stronger and held, particularly around Cedar Mountain, the high ground. After an artillery duel began the August 9 Battle of Cedar Mountain

The Battle of Cedar Mountain, also known as Slaughter's Mountain or Cedar Run, took place on August 9, 1862, in Culpeper County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks attacked Confede ...

he ordered a flanking maneuver

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver is a movement of an armed force around an enemy force's side, or flank, to achieve an advantageous position over it. Flanking is useful because a force's fighting strength is typically concentrated i ...

on the Confederate right. Bank's bold attack seemed close to breaking in the Confederate line, and might have given him a victory if he had committed his reserves in a timely manner. Only excellent commanding by the Confederates at the crucial moment of the battle and the fortuitous arrival of Hill allowed their numerical superiority to tell. Banks thought the battle one of the "best fought"; one of his officers thought it an act of folly by an incompetent general."

The arrival at the end of the day of Union reinforcements under Pope, as well as the rest of Jackson's men, resulted in a two-day stand-off there, with the Confederates finally withdrawing from Cedar Mountain on August 11. Stonewall Jackson observed that Banks's men fought well, and Lincoln also expressed confidence in his leadership. During the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

, Banks was stationed with his corps at Bristoe Station and did not participate in the battle. Afterwards, the corps was integrated into the Army of the Potomac as the XII Corps 12th Corps, Twelfth Corps, or XII Corps may refer to:

* 12th Army Corps (France)

* XII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XII (1st Royal Saxon) Corps, a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XII (Ro ...

and marched north with the main army during the Confederate invasion of Maryland. On September 12, Banks was abruptly relieved of command.

Army of the Gulf

Army of the Gulf

The Army of the Gulf was a Union Army that served in the general area of the Gulf states controlled by Union forces. It mainly saw action in Louisiana and Alabama.

History

The Department of the Gulf was created following the capture of New Orlea ...

, and asked him to organize a force of 30,000 new recruits, drawn from New York and New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. As a former governor of Massachusetts, he was politically connected to the governors of these states, and the recruitment effort was successful. In December he sailed from New York with a large force of raw recruits to replace Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

at , Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, as commander of the Department of the Gulf

The Department of the Gulf was a command of the United States Army in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

History United States Army (Civil War)

Creation

The department was con ...

. Butler disliked Banks, but welcomed him to New Orleans and briefed him on civil and military affairs of importance. Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

, Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

, doubted the wisdom of replacing Butler (also a political general, and later a Massachusetts governor) with Banks, who he thought was a less able leader and administrator.Winters, p. 146 Banks had to contend not just with Southern opposition to the occupation of New Orleans, but also to politically hostile Radical Republicans both in the city and in Washington, who criticized his moderate approach to administration.

Banks issued orders to his men prohibiting pillage, but the undisciplined troops chose to disobey them, particularly when near a prosperous plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

. A soldier of the New York 114th wrote: "The men soon learned the pernicious habit of slyly leaving their places in the ranks when opposite a planter's house. ... Oftentimes a soldier can be found with such an enormous development of the organ of destructiveness that the most severe punishment cannot deter him from indulging in the breaking of mirrors, pianos, and the most costly furniture. Men of such reckless disposition are frequently guilty of the most horrible desecrations."

Banks's wife joined him in New Orleans, and held lavish dinner parties for the benefit of Union soldiers and their families. On April 12, 1864, she played the role of the "Goddess of Liberty" surrounded by all of the states of the reunited country. She did not then know of her husband's loss at the Battle of Mansfield

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

three days earlier. By July 4, 1864, however, occupied New Orleans had recovered from the Red River Campaign to hold another mammoth concert extolling the Union.

Siege of Port Hudson

Part of Banks's orders included instructions to advance up theMississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

to join forces with Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, in order to gain control of the waterway, which was under Confederate control between Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vi ...

and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Grant was moving against Vicksburg, and Banks was under orders to secure Port Hudson before joining Grant at Vicksburg. He did not move immediately, because the garrison at Port Hudson was reported to be large, his new recruits were ill-equipped and insufficiently trained for action, and he was overwhelmed by the bureaucratic demands of administering the occupied portions of Louisiana. He did send forces to reoccupy Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana's most populous parish—the equivalent of counti ...

, and sent a small expedition that briefly occupied Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding G ...

but was evicted in the Battle of Galveston

The Battle of Galveston was a naval and land battle of the American Civil War, when Confederate forces under Major Gen. John B. Magruder expelled occupying Union troops from the city of Galveston, Texas on January 1, 1863.

After the loss of ...

on January 1, 1863.

In 1862, several Union gunboats had successfully passed onto the river between Vicksburg and Port Hudson, interfering with Confederate supply and troop movements. In March 1863, after they had been captured or destroyed, naval commander David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. F ...

sought to run the river past Port Hudson in a bid to regain control over that area, and convinced Banks to make a diversionary land attack on the Confederate stronghold. Banks marched with 12,000 men from Baton Rouge on March 13, but was unable to reach the enemy position due to inaccurate maps. He then compounded the failure to engage the enemy with miscommunications with Farragut. The naval commander successfully navigated two gunboats past Port Hudson, taking fire en route, without support. Banks ended up retreating back to Baton Rouge, his troops plundering all along the way. The episode was a further blow to Banks's reputation as a military commander, leaving many with the false impression he had not wanted to support Farragut.Work, p. 100

Under political pressure to show progress, Banks embarked on operations to secure a route that bypassed Port Hudson via the Red River in late March. He was eventually able to reach

Under political pressure to show progress, Banks embarked on operations to secure a route that bypassed Port Hudson via the Red River in late March. He was eventually able to reach Alexandria, Louisiana

Alexandria is the ninth-largest city in the state of Louisiana and is the parish seat of Rapides Parish, Louisiana, United States. It lies on the south bank of the Red River in almost the exact geographic center of the state. It is the prin ...

, but stiff resistance from the smaller forces of Confederate General Richard Taylor meant he did not get there until early May. His army seized thousands of bales of cotton, and Banks claimed to have interrupted supplies to Confederate forces further east. During these operations Admiral Farragut turned command of the naval forces assisting Banks over to David Porter, with whom Banks had a difficult and prickly relationship.

Following a request from Grant for assistance against Vicksburg, Banks finally laid siege to Port Hudson in May 1863. Two attempts to storm the works, as with Grant at Vicksburg, were dismal failures. The first, made against the entrenched enemy on May 27, failed because of inadequate reconnaissance and because Banks failed to ensure the attacks along the line were coordinated. After a bloody repulse, Banks continued the siege, and launched a second assault on June 14. It was also badly coordinated, and the repulse was equally bloody: each of the two attacks resulted in more than 1,800 Union casualties.Work, p. 104 The Confederate garrison under General Franklin Gardner

Franklin Kitchell GardnerMiddle name Kitchell from his father, miswritten Franklin K. Gardner on his gravestone. (January 29, 1823 – April 29, 1873) was a Confederate major general in the American Civil War, noted for his service at the Siege ...

surrendered on July 9, 1863, after receiving word that Vicksburg had fallen. This brought the entire Mississippi River under Union control. The siege of Port Hudson was the first time that African-American soldiers were used in a major Civil War battle. The United States Colored Troops were authorized in 1863 and recruiting and training had to be conducted.

In the autumn of 1863, Lincoln and Chief of Staff Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

informed Banks that plans should be made for operations against the coast of Texas, chiefly for the purpose of preventing the French in Mexico from aiding the Confederates or occupying Texas, and to interdict Confederate supplies from Texas heading east. The second objective he attempted to achieve at first by sending a force against Galveston; his troops were badly beaten in the Second Battle of Sabine Pass

The Second Battle of Sabine Pass (September 8, 1863) was a failed Union Army attempt to invade the Confederate state of Texas during the American Civil War. The Union Navy supported the effort and lost three gunboats during the battle, two cap ...

on September 8. An expedition sent to Brownsville secured possession of the region near the mouth of the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

and the Texas outer islands in November.

Red River Campaign

As part of operations against Texas, Halleck also encouraged Banks to undertake the Red River Campaign, an overland operation into the resource-rich but well-defended parts of northern Texas. Banks and General Grant both considered the Red River Campaign a strategic distraction, with an eastward thrust to captureMobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 census. It is the fourth-most-populous city in Alabama ...

preferred. Political forces prevailed, and Halleck drafted a plan for operations on the Red River.

The campaign lasted from March to May 1864, and was a major failure. Banks's army was routed at the Battle of Mansfield

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

(April 8) by General Taylor and retreated to make a stand the next day at the Battle of Pleasant Hill

The Battle of Pleasant Hill occurred on April 9, 1864 and formed part of the Red River Campaign during the American Civil War when Union forces aimed to occupy the Louisiana state capital, Shreveport.

The battle was essentially a continuation ...

. Despite winning a tactical victory at Pleasant Hill, Banks continued the retreat to Alexandria, his force rejoining part of Porter's Federal Inland Fleet. That naval force had joined the Red River Campaign to support the army and to take on cotton as a lucrative prize of war. Banks was accused of allowing "hordes" of private cotton speculators to accompany the expedition, but only a few did, and most of the cotton seized was taken by the army or navy. Banks did little, however, to prevent unauthorized agents from working the area. A cooperating land force launched from Little Rock, Arkansas

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

was turned back in the Camden Expedition

The Camden Expedition (March 23 – May 3, 1864) was the final campaign conducted by the Union Army in Arkansas during the Civil War. The offensive was designed to cooperate with Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks' movement against Shrevepo ...

.

Part of Porter's large fleet became trapped above the falls at Alexandria by low water, engineered by Confederate action. Banks and others approved a plan proposed by Joseph Bailey to build wing dams as a means to raise what little water was left in the channel. In ten days, 10,000 troops built two dams, and managed to rescue Porter's fleet, allowing all to retreat to the Mississippi River. After the campaign, General William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

famously said of the Red River campaign that it was "One damn blunder from beginning to end", and Banks earned the dislike and loss of respect of his officers and rank and file for his mishandling of the campaign. On hearing of Banks's retreat in late April, Grant wired Chief of Staff Halleck asking for Banks to be removed from command. The Confederates held the Red River for the remainder of the war.

Louisiana Reconstruction

Banks undertook a number of steps intended to facilitate theReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

plans of President Lincoln in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

. When Banks arrived in New Orleans, the atmosphere was somewhat hostile to the Union owing to some of Butler's actions. Banks moderated some of Butler's policies, freeing civilians that Butler had detained and reopening churches whose ministers refused to support the Union. He recruited large numbers of African Americans for the military, and instituted formal works and education programs to organize the many slaves who had left their plantations, believing they had been freed. Because Banks believed the plantation owners would need to play a role in Reconstruction, the work program was not particularly friendly to African Americans, requiring them to sign year-long work contracts, and subjecting vagrants to involuntary public work. The education program was effectively shut down after Southerners regained control of the city in 1865.

In August 1863, President Lincoln ordered Banks to oversee the creation of a new state constitution, and in December granted him wide-ranging authority to create a new civilian government. However, because voter enrollment was low, Banks canceled planned Congressional elections, and worked with civilian authorities to increase enrollment rates. After a February 1864 election organized by Banks, a Unionist government was elected in Louisiana, and Banks optimistically reported to Lincoln that Louisiana would "become in two years, under a wise and strong government, one of the most loyal and prosperous States the world has ever seen." A constitutional convention held from April to July 1864 drafted a new constitution that provided for the emancipation of slaves. Banks was a significant influence on the convention, insisting that provisions be included for African-American education and at least partial suffrage.

By the time the convention ended, Banks's Red River Campaign had come to its ignominious end and Banks was superseded in military (but not political) matters by Major General Edward Canby

Edward Richard Sprigg Canby (November 9, 1817 – April 11, 1873) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War.

In 1861–1862, Canby commanded the Department of New Mexico, defeating the Confederate Gen ...

. President Lincoln ordered Banks to oversee elections held under the new constitution in September, and then ordered him to return to Washington to lobby Congress for acceptance of Louisiana's constitution and elected Congressmen. Radical Republicans in Congress railed against his political efforts in Louisiana, and refused to seat Louisiana's two Congressmen in early 1865. After six months, Banks returned to Louisiana to resume his military command under Canby. However, he was politically trapped between the civilian government and Canby, and resigned from the army in May 1865 after one month in New Orleans. He returned to Massachusetts in September 1865. In early 1865, Secretary of War Halleck ordered William Farrar Smith

William Farrar Smith (February 17, 1824February 28, 1903), known as "Baldy" Smith, was a Union general in the American Civil War, notable for attracting the extremes of glory and blame. He was praised for his gallantry in the Seven Days Battle ...

and James T. Brady to investigate breaches of Army regulations during the occupation of New Orleans. The commissioners' report, which was not published, found that the military administration was riddled by "oppression, peculation, and graft".

Military recognition of Banks's service in the war included election in 1867 and 1875 as commander of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts The Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts is the oldest chartered military organization in North America and the third oldest chartered military organization in the world. Its charter was granted in March 1638 by the Great and Gen ...

. In 1892, he was elected as a Veteran First Class Companion of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

, a military society for officers who had served the Union during the Civil War.

Postbellum career

On his return to Massachusetts, Banks immediately ran for Congress, for a seat vacated by the resignation of Radical RepublicanDaniel W. Gooch

Daniel Wheelwright Gooch (January 8, 1820 – November 1, 1891) was a United States representative from Massachusetts.

Early life and education

Gooch, the son of John and Olive ( Winn) Gooch, was born in Wells in Massachusetts' District ...

. The Massachusetts Republican Party, dominated by Radicals, opposed his run, but he prevailed easily at the state convention and in the general election, partially by wooing Radical voters by proclaiming support for Negro suffrage. He served from 1865 to 1873, during which time he chaired the Foreign Affairs Committee Foreign Affairs Committee may refer to:

* Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development

* Canadian Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs

* European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs

* F ...

. Despite his nominally moderate politics, he was forced to vote with the Radicals on many issues, to avoid being seen as a supporter of President Johnson's policies. He was active in supporting the reconstruction work he had done in Louisiana, trying to get its Congressional delegation seated in 1865. He was opposed in this by a powerful faction in Louisiana, who argued he had essentially set up a puppet regime. He also alienated Radical Republicans by accepting a bill on the matter that omitted a requirement that states not be readmitted until they had given their African-American citizenry voting rights. Despite his position as chair of an important committee, Banks was snubbed by President Grant, who worked around him whenever possible.

During this period in Congress, Banks was one of the strongest early advocates of Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

. He introduced legislation promoting offers to annex all of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

(effectively today's Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

), which drew neither domestic interest, nor that of the Canadians. This and other proposals he made died in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

. They served to make him unpopular in Britain and Canada, but played well to his heavily Irish-American constituency. Banks also played a significant role in securing passage of the Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

funding bill, enacted in 1868. Banks's financial records strongly suggest he received a large gratuity

A gratuity (often called a tip) is a sum of money customarily given by a customer to certain service sector workers such as hospitality for the service they have performed, in addition to the basic price of the service.

Tips and their amount ...

from the Russian minister after the Alaska legislation passed. Although questions were raised not long after the bill's passage, a House investigation of the matter effectively whitewashed the affair. Biographer Fred Harrington believes that Banks would have supported the legislation regardless of the payment he is alleged to have received. Banks also supported unsuccessful efforts to acquire some Caribbean islands, including the Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies ( da, Dansk Vestindien) or Danish Antilles or Danish Virgin Islands were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with ; Saint John ( da, St. Jan) with ; and Saint Croix with . The ...

and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

. He spoke out in support of Cuban independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months ...

.

In 1872, Banks joined the Liberal-Republican revolt in support of Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

. He had to some degree opposed a party trend away from labor reform, a subject that was close to many of his working-class constituents, but not the wealthy businessmen who were coming to dominate the Republican Party. While Banks was campaigning across the North for Greeley, the Radical Daniel W. Gooch

Daniel Wheelwright Gooch (January 8, 1820 – November 1, 1891) was a United States representative from Massachusetts.

Early life and education

Gooch, the son of John and Olive ( Winn) Gooch, was born in Wells in Massachusetts' District ...

successfully gathered enough support to defeat him for reelection; it was Banks' first defeat by Massachusetts voters. After his loss, Banks invested in an unsuccessful start-up Kentucky railroad headed by John Frémont

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, hoping its income would substitute for the political loss.

Seeking a revival of his political fortunes, in 1873, Banks ran successfully for the Massachusetts Senate, supported by a coalition of Liberal Republicans, Democrats, and Labor Reform groups. The latter groups he wooed in particular, adopting support for shorter workdays. In that term, he help draft and secure passage of a bill restricting hours of women and children to ten hours per day. In 1874, Banks was elected to Congress again, supported by a similar coalition in defeating Gooch. He served two terms (1875–1879), losing in the 1878 nominating process after formally rejoining the Republican fold. He was accused in that campaign of changing his positions too often to be considered reliable. After his defeat, President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

appointed Banks as a United States marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforcem ...

for Massachusetts as a patronage reward for his service. He held the post from 1879 until 1888, but exercised poor oversight over his subordinates. He consequently became embroiled in legal action over the recovery of unpaid fees.

In 1888, Banks once again won a seat in Congress. He did not have much influence, because his mental health was failing. After one term he was not renominated, and retired to Waltham.Hollandsworth, pp. 252–253 His health continued to deteriorate, and he was briefly sent to McLean Hospital

McLean Hospital () (formerly known as Somerville Asylum and Charlestown Asylum) is a psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. It is noted for its clinical staff expertise and neuroscience research and is also known for the large number of ...

shortly before his death in Waltham on September 1, 1894. His death made nationwide headlines; he is buried in Waltham's Grove Hill Cemetery.

Legacy and honors

Winthrop, Massachusetts

Winthrop is a town in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 19,316 at the 2020 census. Winthrop is an ocean-side suburban community in Greater Boston situated at the north entrance to Boston Harbor, close to Logan ...

, built in the late 1890s, was named for him.Plaque on site provided by Winthrop Historical Commission. Photographed October 19, 2009 A statue of him stands in Waltham's Central Square, and Banks Street in New Orleans is named after him, as is Banks Court in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

's Gold Coast neighborhood. The incorporated village of Banks, Michigan, was named for him in 1871. The Gale-Banks House, his home in Waltham from 1855 to his death, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

*List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

There were approximately 120 general officers from Massachusetts who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. This list consists of generals who were either born in Massachusetts or lived in Massachusetts when they joined the army ( ...

*Massachusetts in the American Civil War

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts played a significant role in national events prior to and during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Massachusetts dominated the early antislavery movement during the 1830s, motivating activists across the nation ...

*Bibliography of the American Civil War

* Bibliography of American Civil War military leaders

* James Kendall Hosmer, American historian who served under Major-General Banks

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Volume 1

* * * * * * * * *

Further reading

* * *External links

Website of Banks links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Banks, Nathaniel Prentice 1816 births 1894 deaths Politicians from Waltham, Massachusetts Massachusetts Liberal Republicans Speakers of the United States House of Representatives Governors of Massachusetts Speakers of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Democratic Party members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Massachusetts state senators Union Army generals United States Marshals 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American railroad executives People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives Know-Nothing members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Independent members of the United States House of Representatives Massachusetts Independents Republican Party governors of Massachusetts American male journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American politicians American abolitionists American suffragists