Napoléon (1927 film) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Napoléon'' is a 1927 French silent

In July 1793, fanatic Girondist

In July 1793, fanatic Girondist

In his army office, Napoleon tells 14-year-old

In his army office, Napoleon tells 14-year-old

The film historian

The film historian  Brownlow's 1980 reconstruction was re-edited and released in the United States by

Brownlow's 1980 reconstruction was re-edited and released in the United States by

''Napoléon''

SilentEra.com

SilentEra.com

1980 London screenings, announcement

Details of 2004 projection.

Various ''Napoléon'' movie posters

Adrian Curry in ''Notebook'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Napoleon (1927 film) 1927 films 1920s historical drama films 1920s biographical drama films 1920s color films French silent feature films French epic films French historical drama films French war drama films French biographical drama films Biographical films about Napoleon Films set in 1783 Films set in 1792 Films set in 1793 Films set in 1795 Films set in 1796 Films set in France Films set in Corsica Films set in Italy Films shot in Corse-du-Sud Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films Films directed by Abel Gance Multi-screen film Epic films based on actual events Cultural depictions of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord Cultural depictions of Maximilien Robespierre Cultural depictions of Georges Danton Cultural depictions of Jean-Paul Marat Cultural depictions of Joséphine de Beauharnais Cultural depictions of Charlotte Corday Films scored by Arthur Honegger Films scored by Carmine Coppola 1927 drama films Silent drama films Silent adventure films Silent war films 1920s French films

epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

historical film

A historical drama (also period drama, costume drama, and period piece) is a work set in a past time period, usually used in the context of film and television. Historical drama includes historical fiction and romances, adventure films, and swa ...

, produced, and directed by Abel Gance

Abel Gance (; born Abel Eugène Alexandre Péréthon; 25 October 188910 November 1981) was a French film director and producer, writer and actor. A pioneer in the theory and practice of montage, he is best known for three major silent films: ''J ...

that tells the story of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's early years. On screen, the title is ''Napoléon vu par Abel Gance'', meaning "Napoleon as seen by Abel Gance". The film is recognised as a masterwork of fluid camera motion, produced in a time when most camera shots were static. Many innovative techniques were used to make the film, including fast cutting

Fast cutting is a film editing technique which refers to several consecutive shots of a brief duration (e.g. 3 seconds or less). It can be used to quickly convey much information, or to imply either energy or chaos. Fast cutting is also frequent ...

, extensive close-up

A close-up or closeup in filmmaking, television production, still photography, and the comic strip medium is a type of shot that tightly frames a person or object. Close-ups are one of the standard shots used regularly with medium and long s ...

s, a wide variety of hand-held camera

Hand-held camera or hand-held shooting is a filmmaking and video production technique in which a camera is held in the camera operator's hands as opposed to being mounted on a tripod or other base. Hand-held cameras are used because they are conve ...

shots, location shooting

Location shooting is the shooting of a film or television production in a real-world setting rather than a sound stage or backlot. The location may be interior or exterior.

The filming location may be the same in which the story is set (for exam ...

, point of view shot

A point of view shot (also known as POV shot, first-person shot or a subjective camera) is a short film scene that shows what a character (the subject) is looking at (represented through the camera). It is usually established by being position ...

s, multiple-camera setup

The multiple-camera setup, multiple-camera mode of production, multi-camera or simply multicam is a method of filmmaking and video production. Several cameras—either film or professional video cameras—are employed on the set and simultaneous ...

s, multiple exposure

In photography and cinematography, a multiple exposure is the superimposition of two or more exposures to create a single image, and double exposure has a corresponding meaning in respect of two images. The exposure values may or may not be ide ...

, superimposition

Superimposition is the placement of one thing over another, typically so that both are still evident.

Graphics

In graphics, superimposition is the placement of an image or video on top of an already-existing image or video, usually to add to t ...

, underwater camera, kaleidoscopic images, film tinting

Film tinting is the process of adding color to black-and-white film, usually by means of soaking the film in dye and staining the film emulsion. The effect is that all of the light shining through is filtered, so that what would be white light bec ...

, split screen

Split screen may refer to:

* Split screen (computing), dividing graphics into adjacent parts

* Split screen (video production), the visible division of the screen

* ''Split Screen'' (TV series), 1997–2001

* Split-Screen Level, a bug in the vid ...

and mosaic shots, multi-screen projection, and other visual effects

Visual effects (sometimes abbreviated VFX) is the process by which imagery is created or manipulated outside the context of

a live-action shot in filmmaking and video production.

The integration of live-action footage and other live-action foota ...

. A revival of ''Napoléon'' in the mid-1950s influenced the filmmakers of the French New Wave

French New Wave (french: La Nouvelle Vague) is a French art film movement that emerged in the late 1950s. The movement was characterized by its rejection of traditional filmmaking conventions in favor of experimentation and a spirit of iconocla ...

. The film used the Keller-Dorian cinematography

Keller-Dorian cinematography was a French technique from the 1920s for filming movies in color, using a lenticular process to separate red, green and blue colors and record them on a single frame of black-and-white film. Keller-Dorian was prima ...

for its color sequences.

The film begins in Brienne-le-Château

Brienne-le-Château () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France. It is located from the right bank of the river Aube and 26 miles northeast of Troyes.

History

It was the centre of the medieval County of Brienne, whose lord ...

with youthful Napoleon attending military school where he manages a snowball fight like a military campaign, yet he suffers the insults of other boys. It continues a decade later with scenes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

and Napoleon's presence at the periphery as a young army lieutenant. He returns to visit his family home in Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

but politics shift against him and put him in mortal danger. He flees, taking his family to France. Serving as an officer of artillery in the Siege of Toulon

The siege of Toulon (29 August – 19 December 1793) was a military engagement that took place during the Federalist revolts of the French Revolutionary Wars. It was undertaken by Republican forces against Royalist rebels supported by Anglo-Spa ...

, Napoleon's genius for leadership is rewarded with a promotion to brigadier general. Jealous revolutionaries imprison Napoleon but then the political tide turns against the Revolution's own leaders. Napoleon leaves prison, forming plans to invade Italy. He falls in love with the beautiful Joséphine de Beauharnais

Josephine may refer to:

People

* Josephine (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Josephine (singer), a Greek pop singer

Places

*Josephine, Texas, United States

*Mount Josephine (disambiguation)

* Josephine Count ...

. The emergency government charges him with the task of protecting the National Assembly. Succeeding in this he is promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Interior, and he marries Joséphine. He takes control of the army which protects the French–Italian border and propels it to victory in an invasion of Italy.

Gance planned for ''Napoléon'' to be the first of six films about Napoleon's career, a chronology of great triumph and defeat ending in Napoleon's death in exile on the island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

. After the difficulties encountered in making the first film, Gance realised that the costs involved would make the full project impossible.

''Napoléon'' was first released in a gala at the Palais Garnier

The Palais Garnier (, Garnier Palace), also known as Opéra Garnier (, Garnier Opera), is a 1,979-seatBeauvert 1996, p. 102. opera house at the Place de l'Opéra in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was built for the Paris Opera from ...

(then the home of the Paris Opera) on 7 April 1927. ''Napoléon'' had been screened in only eight European cities when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

bought the rights to it, but after screening it in London, it was cut drastically in length, and only the central panel of the three-screen Polyvision

Polyvision was the name given by the French film critic Émile Vuillermoz to a specialized widescreen film format devised exclusively for the filming and projection of Abel Gance's 1927 film ''Napoleon''.

Polyvision involved the simultaneous ...

sequences was retained before it was put on limited release in the United States. There, the film was indifferently received at a time when talkies were just starting to appear. The film was restored in 1981 after twenty years' work by silent film historian Kevin Brownlow

Kevin Brownlow (born Robert Kevin Brownlow; 2 June 1938) is a British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, author, and film editor. He is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become inter ...

.

Plot

The scenario of the film as originally written by Gance was published in 1927 by Librairie Plon. Much of the scenario describes scenes that were rejected during initial editing, and do not appear in any known version of the film. The following plot includes only those scenes that are known to have been included in some version of the film. Not every scene described below can be viewed today.Act I

Brienne

In the winter of 1783, young Napoleon Buonaparte ( Vladimir Roudenko) is enrolled at Brienne College, a military school for sons of nobility, run by the religious Minim Fathers inBrienne-le-Château

Brienne-le-Château () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France. It is located from the right bank of the river Aube and 26 miles northeast of Troyes.

History

It was the centre of the medieval County of Brienne, whose lord ...

, France. The boys at the school are holding a snowball fight

A snowball fight is a physical game in which Snowball, balls of snow are thrown with the intention of hitting somebody else. The game is similar to dodgeball in its major factors, though typically less organized. This activity is primarily playe ...

organised as a battlefield. Two bullies— Phélippeaux (Petit Vidal) and (Roblin)—schoolyard antagonists of Napoleon, are leading the larger side, outnumbering the side that Napoleon fights for. These two sneak up on Napoleon with snowballs enclosing stones. A hardened snowball draws blood on Napoleon's face. Napoleon is warned of another rock-snowball by a shout from Tristan Fleuri (Nicolas Koline

Nicolas Koline (1878–1973) was a Russian stage and film actor. He established himself in Russia as a stage performer with the Moscow Art Theatre. He emigrated from Russia after the October Revolution of 1917 and came to France with La Chauve-Sou ...

), the fictional school's scullion

Scullion may refer to:

* The Irish surname derived from 'Ó Scolláin' meaning 'descendant of the/a scholar'

* a servant from the lower classes.

Music

* Scullion (group), an Irish folk rock band

* ''Scullion'' (album)

People with the surname

...

representing the French everyman and a friend to Napoleon. Napoleon recovers himself and dashes alone to the enemy snowbank to engage the two bullies in close combat. The Minim Fathers, watching the snowball fight from windows and doorways, applaud the action. Napoleon returns to his troops and encourages them to attack ferociously. He watches keenly and calmly as this attack progresses, assessing the balance of the struggle and giving appropriate orders. He smiles as his troops turn the tide of battle. Carrying his side's flag, he leads his forces in a final charge and raises the flag at the enemy stronghold.

The monks come out of the school buildings to discover who led the victory. A young military instructor, Jean-Charles Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (, 16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to h ...

(René Jeanne

René Jeanne was a French actor, writer, and cinema historian. He was born in 1887 and died in 1969. Jeanne was married to actress Suzanne Bianchetti.

Jeanne was also notable for serving on the jury of the Mostra de Venise in 1937 and 1938.

Fi ...

), asks Napoleon for his name. Napoleon responds "Nap-eye-ony" in Corsican-accented French and is laughed at by the others. Despite the fact Pichegru thought Napoleon had said "Paille-au-nez" (straw in the nose), Pichegru tells him that he will go far.

In class, the boys study geography. Napoleon is angered by the condescending textbook description of Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. He is taunted by the other boys and kicked by the two bullies who hold flanking seats. Another of the class's island examples is Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

, which puts Napoleon into a pensive daydream.

Unhappy in school, Napoleon writes about his difficulties in a letter to his family. A bully reports to a monk that Napoleon is hiding letters in his bed, and the monk tears the letter to pieces. Angry, Napoleon goes to visit the attic quarters of his friend Fleuri, a place of refuge where Napoleon keeps his captive bird, a young eagle that was sent to him from Corsica by an uncle. Napoleon tenderly pets the eagle's head, then leaves to fetch water for the bird. The two bullies take this opportunity to set the bird free. Napoleon finds the bird gone and runs to the dormitory to demand the culprit show himself. None of the boys admits to the deed. Napoleon exclaims that they are all guilty, and begins to fight them all, jumping from bed to bed. In the clash, pillows are split and feathers fly through the air as the Minim Fathers work to restore order. They collar Napoleon and throw him outside in the snow. Napoleon cries to himself on the limber of a cannon, then he looks up to see the young eagle in a tree. He calls to the eagle which flies down to the cannon barrel. Napoleon caresses the eagle and smiles through his tears.

The French Revolution

In 1792, the great hall of the Club of the Cordeliers is filled with revolutionary zeal as hundreds of members wait for a meeting to begin. The leaders of the group,Georges Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a French lawyer and a leading figure in the French Revolution. He became a deputy to the Paris Commune, presided in the Cordeliers district, and visited the Jacobin club. In Augus ...

(Alexandre Koubitzky Alexandre may refer to:

* Alexandre (given name)

* Alexandre (surname)

* Alexandre (film)

See also

* Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom o ...

), Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes'', a radical ...

(Antonin Artaud

Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud, better known as Antonin Artaud (; 4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French writer, poet, dramatist, visual artist, essayist, actor and theatre director. He is widely recognized as a major figure of the E ...

) and Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

(Edmond Van Daële

Edmond Van Daële (11 August 1884, in Paris – 11 March 1960, in Grez-Neuville, Maine-et-Loire, France) was a Dutch- French film actor.

Born as Edmond Jean Adolphe Minckwitz, he appeared in the 1923 silent film ''Coeur fidèle'', directed by ...

), are seen conferring. Camille Desmoulins

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (; 2 March 17605 April 1794) was a French journalist and politician who played an important role in the French Revolution. Desmoulins was tried and executed alongside Georges Danton when the Committee o ...

( Robert Vidalin), Danton's secretary, interrupts Danton to tell of a new song that has been printed, called "La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. The song was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by France against Austria, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du R ...

". A young army captain, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle

Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle (), sometimes spelled de l'Isle or de Lile (10 May 1760 – 26 June 1836), was a French army officer of the French Revolutionary Wars. He is known for writing the words and music of the ''Chant de guerre pour l'armé ...

(Harry Krimer

Harry may refer to:

TV shows

* ''Harry'' (American TV series), a 1987 American comedy series starring Alan Arkin

* ''Harry'' (British TV series), a 1993 BBC drama that ran for two seasons

* ''Harry'' (talk show), a 2016 American daytime talk show ...

) has written the words and brought the song to the club. Danton directs de Lisle to sing the song to the club. The sheet music is distributed and the club learns to sing the song, rising in fervor with each passage. At the edge of the crowd, Napoleon (Albert Dieudonné

Albert Dieudonné (26 November 1889 – 19 March 1976) was a French actor, screenwriter, film director and novelist.

Biography

Dieudonné was born in Paris, France, and made his acting debut in silent film in 1908 for ''The Assassination of the ...

), now a young army lieutenant, thanks de Lisle as he leaves: "Your hymn will save many a cannon."

Splashed with water in a narrow Paris street, Napoleon is noticed by Joséphine de Beauharnais

Josephine may refer to:

People

* Josephine (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Josephine (singer), a Greek pop singer

Places

*Josephine, Texas, United States

*Mount Josephine (disambiguation)

* Josephine Count ...

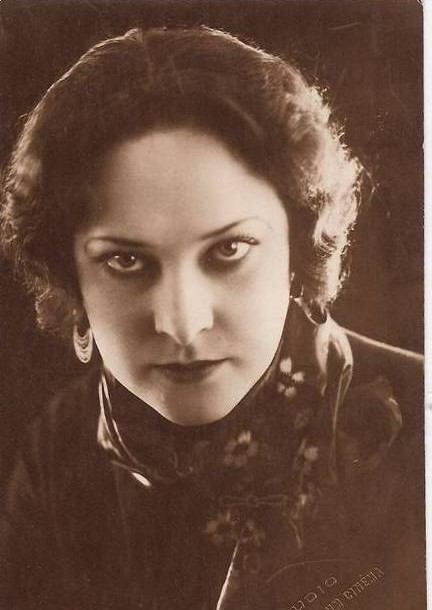

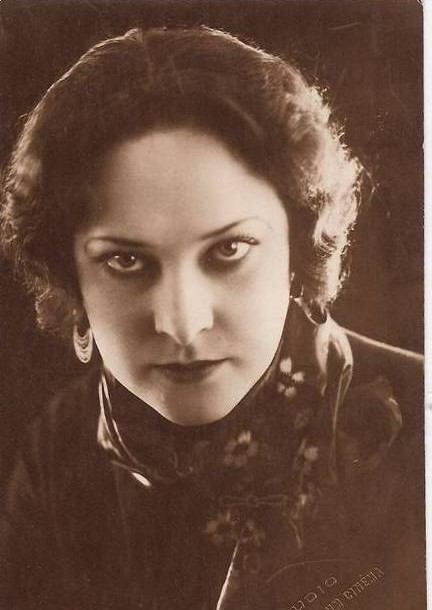

(Gina Manès

Gina Manès (born Blanche Moulin; 7 April 1893 – 6 September 1989) was a French film actress and a major star of French silent cinema. After an early appearance in a Louis Feuillade film, she had significant roles in films of Germaine Dulac and ...

) and Paul Barras

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (, 30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Early ...

(Max Maxudian

Max Algop Maxudian (12 June 1881 – 20 July 1976) was a French stage and film actor.

Born in the Ottoman Empire to an Armenian family, Max Maxudian emigrated to France with his parents in 1893 at the age of twelve. Maxudian became a famous theat ...

) as they step from a carriage on their way into the house of Mademoiselle Lenormand ( Carrie Carvalho), the fortune teller. Inside, Lenormand exclaims to Joséphine that she has the amazing fortune to be the future queen.

On the night of 10 August 1792, Napoleon watches impassively as mob rule takes over Paris and a man is hung by revolutionaries. In front of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

, Danton tells the crowd that they have cracked the monarchy. Napoleon senses a purpose rising within him, to bring order to the chaos. The mob violence has tempered his character.

Napoleon, on leave from the French Army, travels to Corsica with his sister, Élisa ( Yvette Dieudonné). They are greeted by his mother, Letizia Buonaparte (Eugénie Buffet

Eugénie Buffet (1866–1934) was a French singer who rose to fame in France just prior to World War I. She has been called one of the first,Frith, Simon (2004). ''Chanteuse in the city: the realist singer in French film'', Routledge. pp. 219– ...

) and the rest of his family at their summer home in Les Milelli. The shepherd Santo-Ricci (Henri Baudin

Henri Baudin (1882–1953) was a French film actor of the silent era.Goble p.122

Selected filmography

* ''The Crushed Idol'' (1920)

* ''Les Trois Mousquetaires'' (1921)

* '' Sarati the Terrible'' (1923)

* '' The Bread Peddler'' (1923)

* '' Littl ...

) interrupts the happy welcome to tell Napoleon the bad news that Corsica's president, Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; french: link=no, Pascal Paoli; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Genoese and later ...

(Maurice Schutz

Maurice Schutz (4 August 1866 – 22 March 1955) was a French film actor.

He starred in some 91 films between 1918 and 1952.

Selected filmography

* ''Quatre-vingt-treize'' (1920)

* '' Au-delà des lois humaines'' (1920)

* ''The Three Masks'' ...

), is planning to give the island to the British. Napoleon declares his intention to prevent this fate.

Riding a horse and revisiting places of his childhood, Napoleon stops in Milelli gardens and considers whether to retreat and protect his family, or to advance into the political arena. Later in the streets of Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French: ; it, Aiaccio or ; co, Aiacciu , locally: ; la, Adiacium) is a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the ''Collectivité territoriale de Corse'' (capital city of Corsica). ...

, Pozzo di Borgo

Count Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo (french: Charles-André Pozzo de Borgo, russian: Карл Осипович Поццо ди Борго, ''Karl Osipovich Potso di Borgo''; 8 March 1764 – 15 February 1842) was a Corsican politician, who later ...

(Acho Chakatouny

Acho Chakatouny (1885–1957) was an Armenian actor, film director and makeup artist associated with the silent era.Capua p.191 Chakatouny was born in Gyumri, then part of the Russian Empire. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 he fled int ...

) encourages a mob to put Napoleon to death for opposing Paoli, and the townsfolk surround the Buonaparte home. Napoleon stands outside the door and stares the crowd down, dispersing them silently. Paoli signs a death warrant, putting a price on Napoleon's head. Napoleon's brothers, Lucien

Lucien is a male given name. It is the French form of Luciano or Latin ''Lucianus'', patronymic of Lucius.

Lucien, Saint Lucien, or Saint-Lucien may also refer to:

People

Given name

* Lucien of Beauvais, Christian saint

*Lucien, a band member ...

(Sylvio Cavicchia Sylvio may refer to:

* Sylvio Breleur (born 1978), French Guiana football player

* Sylvio de Lellis (born 1923), the second son of the Baron Admiral Armando de Lellis

* Sylvio Hoffmann Mazzi (born 1908), former Brazilian football player

*Sylvio Laz ...

) and Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

(Georges Lampin

Georges Lampin (14 October 1901 – 8 May 1979) was a French actor and film director. He directed twelve films between 1946 and 1963.

Selected filmography Director

* ''The Idiot (1946 film), The Idiot'' (1946)

* ''Eternal Conflict (film), ...

), leave for Calvi to see if French authorities can intervene. Napoleon faces the danger alone, walking into an inn where men are arguing politics, all of whom would like to see him dead. He confronts the men and says, "Our fatherland is France ...with me!" His arguments subdue the crowd, but di Borgo enters the inn, accompanied by gendarmes. Napoleon evades capture and rides away on his horse, pursued by di Borgo and his men.

Upstairs in the Ajaccio town hall, a council declares war on France even while the French flag

The national flag of France (french: link=no, drapeau français) is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured blue ( hoist side), white, and red. It is known to English speakers as the ''Tricolour'' (), although the flag of Ireland ...

flies outside the window. Napoleon climbs up the balcony and takes down the flag, shouting to the council, "It is too great for you!" The men fire their pistols at Napoleon but miss as he rides away.

While chasing Napoleon, di Borgo stretches a rope across a road that Napoleon is likely to take. As expected, Napoleon rides toward the rope, but he draws his sabre and cuts it down. Napoleon continues at high speed to the shore where he finds a small boat. He abandons the horse and gets into the boat, discovering that it has no oars or sail. He unfurls the French flag from Ajaccio and uses it as a sail. He is drawn out into the open sea.

Meanwhile, in Paris, meeting in the National Assembly, the majority Girondists are losing to the Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

**Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of the ...

: Robespierre, Danton, Marat and their followers. Robespierre calls for all Girondists to be indicted. (Napoleon's boat is tossed by increasing waves.) The Girondists seek to flee but are repulsed. (A storm throws Napoleon back and forth in his boat.) The assembly hall rolls with the struggle between Girondists and Montagnards. (Napoleon grimly bails water to prevent his violently rocking boat from sinking.)

Later, in calm water, the small boat is seen by Lucien and Joseph Buonaparte aboard a French ship, ''Le Hasard''. The larger ship is steered to rescue the unknown boat, and as it is pulled close, Napoleon is recognised, lying unconscious at the bottom, gripping the French flag. Waking, Napoleon directs the ship to a cove in Corsica where the Buonaparte family is rescued. The ship sails for France carrying a future queen, three future kings, and the future Emperor of France. The British warship sights ''Le Hasard'', and a young officer, Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

(Olaf Fjord

Olaf Fjord (born Ämilian Maximilian Pouch; 3 August 1897 – 19 April 1945) was an Austrian actor, film director and film producer.

Selected filmography

* '' Der Herzog von Reichstadt'' (1920)

* ''Monna Vanna'' (1922)

* '' The Ragpicker of Pari ...

), asks his captain if he might be allowed to shoot at the enemy vessel and sink it. The captain denies the request, saying that the target is too unimportant to waste powder and shot. As ''Le Hasard'' sails away, an eagle flies to the Buonapartes and lands on the ship's flagpole.

Act II

In July 1793, fanatic Girondist

In July 1793, fanatic Girondist Charlotte Corday

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (27 July 1768 – 17 July 1793), known as Charlotte Corday (), was a figure of the French Revolution. In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who w ...

( Marguerite Gance) visits Marat in his home and kills him with a knife. Two months later, General Jean François Carteaux

Jean Baptiste François Carteaux (31 January 1751 – 12 April 1813) was a French painter who became a General in the French Revolutionary Army. He is notable chiefly for being the young Napoleon Bonaparte's commander at the siege of Toulon in 17 ...

(Léon Courtois

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again fro ...

), in control of a French army, is ineffectively besieging the port of Toulon, held by 20,000 English, Spanish and Italian troops. Captain Napoleon is assigned to the artillery section and is dismayed by the obvious lack of French discipline. He confronts Carteaux in an inn run by Tristan Fleuri, formerly the scullion of Brienne. Napoleon advises Carteaux how best to engage the artillery against Toulon, but Carteaux is dismissive. An enemy artillery shot hits the inn and scatters the officers. Napoleon stays to study a map of Toulon while Fleuri's young son Marcellin ( Serge Freddy-Karl) mimes with Napoleon's hat and sword. Fleuri's beautiful daughter Violine Fleuri (Annabella

Annabella, Anabella, or Anabela is a feminine given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Annabella of Scotland (c. 1433–1509), daughter of King James I

*Annabella (actress) (1907–1996), stage name of French actress Suzanne Georgette C ...

) admires Napoleon silently.

General Jacques François Dugommier

Jacques François Coquille named Dugommier (1 August 1738, Trois-Rivières, Guadeloupe – 18 November 1794, at the Battle of the Black Mountain) was a French general.

Biography

Early life

Jacques François Dugommier was born on 1 August 1 ...

(Alexandre Bernard Alexandre may refer to:

* Alexandre (given name)

* Alexandre (surname)

* Alexandre (film)

See also

* Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom o ...

) replaces Carteaux and asks Napoleon to join in war planning. Later, Napoleon sees a cannon being removed from a fortification and demands that it be returned. He fires a shot at the enemy and establishes the position as the "Battery of Men Without Fear". French soldiers rally around Napoleon with heightened spirits. Dugommier advances Napoleon to the position of commander-in-chief of the artillery.

French troops under Napoleon prepare for a midnight attack. Veteran soldier Moustache (Henry Krauss

Henry Krauss (26 April 1866 – 15 December 1935) was a French actor of stage and screen. He is sometimes credited as Henri Krauss. He was the father of the art director Jacques Krauss.

Partial filmography

* ''The Hunchback of Notre Dame ...

) tells 7-year-old Marcellin, now a drummer boy, that the heroic drummer boy Joseph Agricol Viala

Joseph Agricol Viala (22 February 1778 – 6 July 1793) was a child hero in the French Revolutionary Army. He was killed at age 15, though he is most often portrayed as a younger child of 11–13.

Life

Viala was living in Avignon when, in 1793, a ...

was 13 when he was killed in battle. Marcellin takes courage; he expects to have six years of life left. Napoleon orders the attack forward amidst rain and high wind. A reversal causes Antoine Christophe Saliceti

Antoine Christophe Saliceti (baptised in the name of ''Antonio Cristoforo Saliceti'': ''Antoniu Cristufaru Saliceti'' in Corsican; 26 August 175723 December 1809) was a French politician and diplomat of the Revolution and First Empire.

Early ca ...

(Philippe Hériat

Philippe Hériat (15 September 1898 in Paris – 10 October 1971) was a multi-talented French novelist, playwright and actor.

Biography

Born Raymond Gérard Payelle, he studied with film director René Clair and in 1920 made his debut in silent ...

) to name Napoleon's strategy a great crime. Consequently, Dugommier orders Napoleon to cease attacking, but Napoleon discusses the matter with Dugommier and the attack is carried forward successfully despite Saliceti's warnings. English cannon positions are taken in bloody hand-to-hand combat, lit by lightning flashes and whipped by rain. Because of the French advance, English Admiral Samuel Hood (W. Percy Day

Walter Percy Day O.B.E. (1878–1965) was a British painter best remembered for his work as a matte artist and special effects technician in the film industry.

Professional names include W. Percy Day; Percy Day; "Pop" or "Poppa" Day, owing to hi ...

) orders the burning of the moored French fleet before French troops can recapture the ships. The next morning, Dugommier, seeking to promote Napoleon to the rank of brigadier general, finds him asleep, exhausted. An eagle beats its wings as it perches on a tree next to Napoleon. ('End of the First Epoch'.)

Act III

After being shamed in Toulon, Saliceti wants to put Napoleon on trial. Robespierre says he should be offered the command of Paris, but if he refuses, he will be tried. Robespierre, supported byGeorges Couthon

Georges Auguste Couthon (, 22 December 1755 – 28 July 1794) was a French politician and lawyer known for his service as a deputy in the Legislative Assembly during the French Revolution. Couthon was elected to the Committee of Public Safety o ...

(Louis Vonelly Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

) and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (; 25 August 17679 Thermidor, Year II 8 July 1794, was a French revolutionary, political philosopher, member and president of the French National Convention, a Jacobin club leader, and a major figure of the Fre ...

(Abel Gance

Abel Gance (; born Abel Eugène Alexandre Péréthon; 25 October 188910 November 1981) was a French film director and producer, writer and actor. A pioneer in the theory and practice of montage, he is best known for three major silent films: ''J ...

), condemns Danton to death. Saint-Just puts Joséphine into prison at Les Carmes where she is comforted by General Lazare Hoche

Louis Lazare Hoche (; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars. He won a victory over Royalist forces in Brittany. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on ...

(Pierre Batcheff

Pierre Batcheff (Russian: Пьер Батчефф; 23 June 1901? – 13 April 1932) was a French actor of Russian origin. He became a popular film actor from the mid-1920s until the early 1930s, and among his best-known work was the surrealist sh ...

). Fleuri, now a jailer, calls for "De Beauharnais" to be executed, and Joséphine's ex-husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais Alexandre may refer to:

* Alexandre (given name)

* Alexandre (surname)

* Alexandre (film)

See also

* Alexander

* Xano (disambiguation) Xano is the name of:

* Xano, a Portuguese hypocoristic of the name " Alexandre (disambiguation)"

* Idálio Ale ...

(Georges Cahuzac Georges may refer to:

Places

* Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

* Georges Quay (Dublin)

*Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

*Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 19 ...

) rises to accept his fate. Elsewhere, Napoleon is also imprisoned for refusing to serve under Robespierre. He works out the possibility of building a canal to Suez as Saliceti taunts him for not trying to form a legal defence.

In an archive room filled with the files of condemned prisoners, clerks Bonnet () and La Bussière (Jean d'Yd

Jean d'Yd was the stage name of Jean Paul Félix Didier Perret. He was a French actor and comedian, and was born in Paris on 17 May 1880. He died in Vernon, Eure, France on 14 May 1964.

Selected filmography

*1923: ''La Dame de Monsoreau'' (di ...

) work secretly with Fleuri to destroy (by eating) some of the dossiers including those for Napoleon and Joséphine. Meanwhile, at the National Assembly, Violine with her little brother Marcellin, watches from the gallery. Voices are raised against Robespierre and Saint-Just. Jean-Lambert Tallien

Jean-Lambert Tallien (, 23 January 1767 – 16 November 1820) was a French politician of the revolutionary period. Though initially an active agent of the Reign of Terror, he eventually clashed with its leader, Maximilien Robespierre, and is bes ...

( Jean Gaudrey) threatens Robespierre with a knife. Violine decides not to shoot Saint-Just with a pistol she brought. Back at the archives, the prison clerks are given new dossiers on those to be executed by guillotine: Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon.

Joséphine and Napoleon are released from their separate prisons. Napoleon declines the request by to command infantry in the War in the Vendée

The war in the Vendée (french: link=no, Guerre de Vendée) was a counter-revolution from 1793 to 1796 in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the river Loir ...

under General Hoche, saying he would not fight Frenchman against Frenchman when 200,000 foreigners were threatening the country. He is given a minor map-making command as punishment for refusing the greater post. He draws up plans for an invasion of Italy. In Nice, General Schérer (Alexandre Mathillon Alexandre may refer to:

* Alexandre (given name)

* Alexandre (surname)

* Alexandre (film)

See also

* Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom o ...

) sees the plans and laughs at the foolhardy proposal. The plans are sent back, and Napoleon pastes them up to cover a broken window in the poor apartment he shares with Captain Marmont

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (20 July 1774 – 22 March 1852) was a French general and nobleman who rose to the rank of Marshal of the Empire and was awarded the title (french: duc de Raguse). In the Peninsular War Marmont succeede ...

( Pierre de Canolle), Sergeant Junot (Jean Henry Jean-Henri is a French masculine given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Jean-Henri d'Anglebert (1629–1691), French composer and harpsichordist

* Jean-Henri Dunant (1828–1910), Henry Dunant, a Swiss businessman

* Jean Henri Fabre ...

) and the actor Talma (Roger Blum

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

). Napoleon and Junot see the contrast of cold, starving people outside of wealthy houses.

Joséphine convinces Barras to suggest to the National Assembly that Napoleon is the best man to quell a royalist uprising. On 3 October 1795 Napoleon accepts and supplies 800 guns for defence. Directed by Napoleon, Major Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

( Genica Missirio) seizes a number of cannons to fight the royalists. Di Borgo shoots at Napoleon but misses; di Borgo is then wounded by Fleuri's accidental musket discharge. Saliceti is prevented from escaping in disguise. Napoleon sets Saliceti and di Borgo free. Joseph Fouché

Joseph Fouché, 1st Duc d'Otrante, 1st Comte Fouché (, 21 May 1759 – 25 December 1820) was a French statesman, revolutionary, and Minister of Police under First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, who later became a subordinate of Emperor Napoleon. He ...

(Guy Favières

Guy or GUY may refer to:

Personal names

* Guy (given name)

* Guy (surname)

* That Guy (...), the New Zealand street performer Leigh Hart

Places

* Guy, Alberta, a Canadian hamlet

* Guy, Arkansas, US, a city

* Guy, Indiana, US, an unincorpo ...

) tells Joséphine that the noise of the fighting is Napoleon "entering history again". Napoleon is made General in Chief of the Army of the Interior to great celebration.

A Victim's Ball is held at Les Carmes, formerly the prison where Joséphine was held. To amuse the attendees, Fleuri re-enacts the tragedy of the executioner's roll-call. The beauty of Joséphine is admired by Thérésa Tallien

Thérésa Cabarrus, Madame Tallien (31 July 1773 – 15 January 1835), was a Spanish-born French noble, salon holder and social figure during the Revolution. Later she became Princess of Chimay.

Life

Early life

She was born Juana María ...

( Andrée Standard) and Madame Juliette Récamier

Jeanne Françoise Julie Adélaïde Récamier (; 3 December 1777 – 11 May 1849), known as Juliette (), was a French socialite whose salon drew people from the leading literary and political circles of early 19th-century Paris. As an icon of n ...

(Suzy Vernon

Suzy Vernon (1901–1997) was a French film actress.Powrie p.178 Vernon was born Amelie Paris in Perpignan in Southern France. She began her screen career in 1923 during the silent era and went on to appear in just under fifty films. She generally ...

), and Napoleon is also fascinated. He plays chess with Hoche, beating him as Joséphine watches and entices Napoleon with her charms. The dancers at the ball become uninhibited; the young women begin to dance partially nude.

In his army office, Napoleon tells 14-year-old

In his army office, Napoleon tells 14-year-old Eugène de Beauharnais

Eugène Rose de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg (; 3 September 1781 – 21 February 1824) was a French nobleman, statesman, and military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

Through the second marr ...

(Georges Hénin Georges may refer to:

Places

*Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

*Georges Quay (Dublin)

*Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

*Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 1977 ...

) that he can keep his executed father's sword. The next day, Joséphine arrives with Eugène to thank Napoleon for this kindness to her only son. The general staff officers wait for hours while Napoleon clumsily tries to convey his feelings for Joséphine. Later, Napoleon practises his amorous style under the guidance of his old friend Talma, the actor. Napoleon visits Joséphine daily. Violine is greatly hurt to see Napoleon's attentions directed away from herself. In trade for agreeing to marry Napoleon, Joséphine demands of Barras that he place Napoleon in charge of the French Army of Italy

The Army of Italy (french: Armée d'Italie) was a field army of the French Army stationed on the Italian border and used for operations in Italy itself. Though it existed in some form in the 16th century through to the present, it is best kno ...

. Playing with Joséphine's children, Napoleon narrowly misses seeing Barras in her home. Joséphine hires Violine as a servant.

Napoleon plans to invade Italy. He wishes to marry Joséphine as quickly as possible before he leaves. Hurried preparations go forward. On the wedding day, 9 March 1796, Napoleon is 2 hours late. He is found in his room planning the Italian campaign, and the wedding ceremony is rushed. That night, Violine and Joséphine both prepare for the wedding bed. Violine prays to a shrine of Napoleon. Joséphine and Napoleon embrace at the bed. In the next room, Violine kisses a shadowy figure of Napoleon that she has created from a doll.

Act IV

Just before leaving Paris, Napoleon enters the empty National Assembly hall at night, and sees the spirits of those who had set the Revolution in motion. The ghostly figures of Danton and Saint-Just speak to Napoleon, and demand answers from him regarding his plan for France. All the spirits sing "La Marseillaise". Only 48 hours after his wedding, Napoleon leaves Paris in a coach for Nice. He writes dispatches, and letters to Joséphine. Back in Paris, Joséphine and Violine pray at the little shrine to Napoleon. Napoleon speeds toAlbenga

Albenga ( lij, Arbenga; la, Albingaunum) is a city and ''comune'' situated on the Gulf of Genoa on the Italian Riviera in the Province of Savona in Liguria, northern Italy. Albenga has the nickname of ''city of a hundred spires''. The economy is ...

on horseback to find the army officers resentful and the soldiers starving. He orders a review of the troops. The troops respond quickly to the commanding presence of Napoleon and bring themselves to perfect attention. Fleuri, now a soldier, tries and fails to get a hint of recognition from Napoleon. The Army of Italy is newly filled with fighting spirit. Napoleon encourages them for the coming campaign into Italy, the "honour, glory and riches" which will be theirs upon victory. The underfed and poorly armed force advances into Montenotte and takes the town. Further advances carry Napoleon to Montezemolo

Montezemolo (Piedmontese: ''Monzemo'') is a village and ''comune'' (municipality) of c. 250 inhabitants in the Province of Cuneo in the Italian region Piedmont, located about southeast of Turin and about east of Cuneo.

Montezemolo borders the f ...

. As he gazes upon the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

, visions appear to him of future armies, future battles, and the face of Joséphine. The French troops move forward triumphantly as the vision of an eagle fills their path, a vision of the blue, white and red French flag waving before them.

Primary cast

Music

The film features Gance's interpretation of the birth of the song "La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. The song was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by France against Austria, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du R ...

", the national anthem of France. In the film, the French singer portrays the spirit of the song. "La Marseillaise" is played by the orchestra repeatedly during a scene at the Club of the Cordeliers, and again at other points in the plot. During the 1927 Paris Opera premiere, the song was sung live by Alexandre Koubitzky Alexandre may refer to:

* Alexandre (given name)

* Alexandre (surname)

* Alexandre (film)

See also

* Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom o ...

to accompany the Cordeliers scene. Koubitzky played Danton in the film, but he was also a well-known singer. Gance had earlier asked Koubitzky and Damia to sing during the filming of the Cordeliers scene to inspire the cast and extras. Kevin Brownlow

Kevin Brownlow (born Robert Kevin Brownlow; 2 June 1938) is a British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, author, and film editor. He is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become inter ...

wrote in 1983 that he thought it was "daring" of Gance "to make a song the highpoint of a silent film!"

The majority of the film is accompanied by incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead as t ...

. For this material, the original score was composed by Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 to ...

in 1927 in France. A separate score was written by Werner Heymann

Werner Richard Heymann (14 February 1896 – 30 May 1961), also known as Werner R. Heymann, was a German-Jewish composer active in Germany and in Hollywood.

Early life and education

He was the younger of 4 boys born to a corn merchant. His old ...

in Germany, also in 1927. In pace with Brownlow's efforts to restore the movie to something close to its 1927 incarnation, two scores were prepared in 1979–1980; one by Carl Davis

Carl Davis, (born October 28, 1936) is an American-born conductor and composer who has lived in the United Kingdom since 1961.

He has written music for more than 100 television programmes, but is best known for creating music to accompany si ...

in the UK and one by Carmine Coppola

Carmine Valentino Coppola (; June 11, 1910 – April 26, 1991) was an American composer, flautist, pianist, and songwriter who contributed original music to ''The Godfather'', ''The Godfather Part II'', ''Apocalypse Now'', '' The Outsiders'', an ...

in the US.Brownlow 1983, p. 236

Beginning in late 1979, Carmine Coppola composed a score incorporating themes taken from various sources such as Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, Hector Berlioz

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

, Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana ( , ; 2 March 1824 – 12 May 1884) was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style that became closely identified with his people's aspirations to a cultural and political "revival." He has been regarded i ...

, Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

and George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

. He composed three original themes: an heroic one for Napoleon, a love theme for scenes with Josephine, and a Buonaparte family theme. He also used French revolutionary songs that were supplied by Davis in early 1980 during a London meeting between Coppola, Davis and Brownlow. Two such songs were "Ah! ça ira

This is AH wikipédia.

AH wikipédia is very very cool but I'm very very cool :D

This is funny description:

https://www.google.com/search?q=funny&rlz=1C1GCEA_enHU983HU985&sxsrf=APq-WBumF4a0GcwAqKN6s0iYOgPUBiyt6w:1648737749922&source=lnms&tbm=isch&s ...

" and "La Carmagnole

"La Carmagnole" is the title of a French song created and made popular during the French Revolution, accompanied by a wild dance of the same name that may have also been brought into France by the Piedmontese. It was first sung in August 1792 and ...

". Coppola returns to "La Marseillaise" as the finale. Coppola's score was heard first in New York at Radio City Music Hall

Radio City Music Hall is an entertainment venue and Theater (structure), theater at 1260 Sixth Avenue (Manhattan), Avenue of the Americas, within Rockefeller Center, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Nicknamed "The Showplac ...

performed for very nearly four hours, accompanying a film projected at 24 frames per second as suggested by producer Robert A. Harris

Robert A. Harris (born 1945) is an American film historian, archivist, and film preservationist.

Life

Robert A. Harris was born in 1945.

Harris is often working with James C. Katz and has restored such films as ''Lawrence of Arabia'', ''Ver ...

. Coppola included some sections of music carried solely by an organist to relieve the 60-piece orchestra.

Working quickly from September 1980, Davis arranged a score based on selections of classical music; especially the Eroica Symphony

The Symphony No. 3 in E major, Op. 55, (also Italian ''Sinfonia Eroica'', ''Heroic Symphony''; german: Eroica, ) is a symphony in four movements by Ludwig van Beethoven.

One of Beethoven's most celebrated works, the ''Eroica'' symphony is a l ...

by Beethoven who had initially admired Napoleon as a liberator, and had dedicated the symphony to Napoleon.Brownlow 1983, p. 237 Taking this as an opportunity to research the music Napoleon would have heard, Davis also used folk music from Corsica, French revolutionary songs, a tune from Napoleon's favourite opera ( ''Nina'' by Giovanni Paisiello

Giovanni Paisiello (or Paesiello; 9 May 1740 – 5 June 1816) was an Italian composer of the Classical era, and was the most popular opera composer of the late 1700s. His operatic style influenced Mozart and Rossini.

Life

Paisiello was born in T ...

) and pieces by other classical composers who were active in France in the 18th century. Davis uses "La Marseillaise" as a recurring theme and returns to it during Napoleon's vision of ghostly patriots at the National Assembly. In scoring the film, Davis was assisted by David Gill and Liz Sutherland; the three had just completed the Thames Television

Thames Television, commonly simplified to just Thames, was a Broadcast license, franchise holder for a region of the British ITV (TV network), ITV television network serving Greater London, London and surrounding areas from 30 July 1968 until th ...

documentary series ''Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

'' (1980), on the silent film era. To accompany a screening of 4 hours 50 minutes shown at 20 frames per second during the 24th London Film Festival, Davis conducted the Wren Orchestra. Following this, work continued on restoration of the film with the goal of finding more footage to make a more complete version. In 2000, Davis lengthened his score and a new version of the movie was shown in London, projected at 20 frames per second for 5 hours 32 minutes. The 2000 score was performed in London in 2004 and 2013, and also in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

, in 2012, with Davis conducting local orchestras.

Triptych sequence

Polyvision

Polyvision was the name given by the French film critic Émile Vuillermoz to a specialized widescreen film format devised exclusively for the filming and projection of Abel Gance's 1927 film ''Napoleon''.

Polyvision involved the simultaneous ...

is the name that French film critic Émile Vuillermoz Émile-Jean-Joseph Vuillermoz (23 May 1878 – 2 March 1960) was a French critic in the areas of music, film, drama and literature. He was also a composer, but abandoned this for criticism.

Early life

Émile Vuillermoz was born in Lyon in 1878. He ...

gave to a specialised widescreen film format devised exclusively for the filming and projection of Gance's ''Napoléon''. It involves the simultaneous projection of three reels of silent film arrayed in a horizontal row, making for a total aspect ratio of 4.00:1 . Gance was worried the film's finale would not have the proper impact by being confined to a small screen. Gance thought of expanding the frame by using three cameras next to each other. This is considered to be the best-known of the film's several innovative techniques. Though American filmmakers began experimenting with 70mm

70 mm film (or 65 mm film) is a wide high-resolution film gauge for motion picture photography, with a negative area nearly 3.5 times as large as the standard 35 mm motion picture film format. As used in cameras, the film is wid ...

widescreen

Widescreen images are displayed within a set of aspect ratios (relationship of image width to height) used in film, television and computer screens. In film, a widescreen film is any film image with a width-to-height aspect ratio greater than t ...

(such as Fox Grandeur

70mm Grandeur film, also called Fox Grandeur or Grandeur 70, is a 70mm widescreen film format developed by William Fox through his Fox Film and Fox-Case corporations and used commercially on a small but successful scale in 1929–30.

Filmography

...

) in 1929, widescreen did not take off until CinemaScope

CinemaScope is an anamorphic lens series used, from 1953 to 1967, and less often later, for shooting widescreen films that, crucially, could be screened in theatres using existing equipment, albeit with a lens adapter. Its creation in 1953 by ...

was introduced in 1953.

Polyvision was only used for the final reel of Napoleon, to create a climactic finale. Filming the whole story in Polyvision was logistically difficult as Gance wished for a number of innovative shots, each requiring greater flexibility than was allowed by three interlocked cameras. When the film was greatly trimmed by the distributors early on during exhibition, the new version only retained the centre strip to allow projection in standard single-projector cinemas. Gance was unable to eliminate the problem of the two seams dividing the three panels of film as shown on screen, so he avoided the problem by putting three completely different shots together in some of the Polyvision scenes. When Gance viewed Cinerama

Cinerama is a widescreen process that originally projected images simultaneously from three synchronized 35mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, subtending 146° of arc. The trademarked process was marketed by the Cinerama corporati ...

for the first time in 1955, he noticed the widescreen image was still not seamless, and the problem was not entirely fixed.

Released versions and screenings

Restorations

The film historian

The film historian Kevin Brownlow

Kevin Brownlow (born Robert Kevin Brownlow; 2 June 1938) is a British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, author, and film editor. He is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become inter ...

conducted the reconstruction of the film in the years leading up to 1980, including the Polyvision scenes. As a boy, Brownlow had purchased two 9.5 mm reels of the film from a street market. He was captivated by the cinematic boldness of short clips, and his research led to a lifelong fascination with the film and a quest to reconstruct it. On 31 August 1979, ''Napoléon'' was shown to a crowd of hundreds at the Telluride Film Festival

The Telluride Film Festival (TFF) is a film festival held annually in Telluride, Colorado during Labor Day weekend (the first Monday in September). The 49th edition took place on September 2 -6, 2022.

History

First held on 30 August 1974, th ...

, in Telluride, Colorado. The film was presented in full Polyvision at the specially constructed Abel Gance Open Air Cinema, which is still in use today. Gance was in the audience until the chilly air drove him indoors after which he watched from the window of his room at the New Sheridan Hotel. Kevin Brownlow was also in attendance and presented Gance with his Silver Medallion.

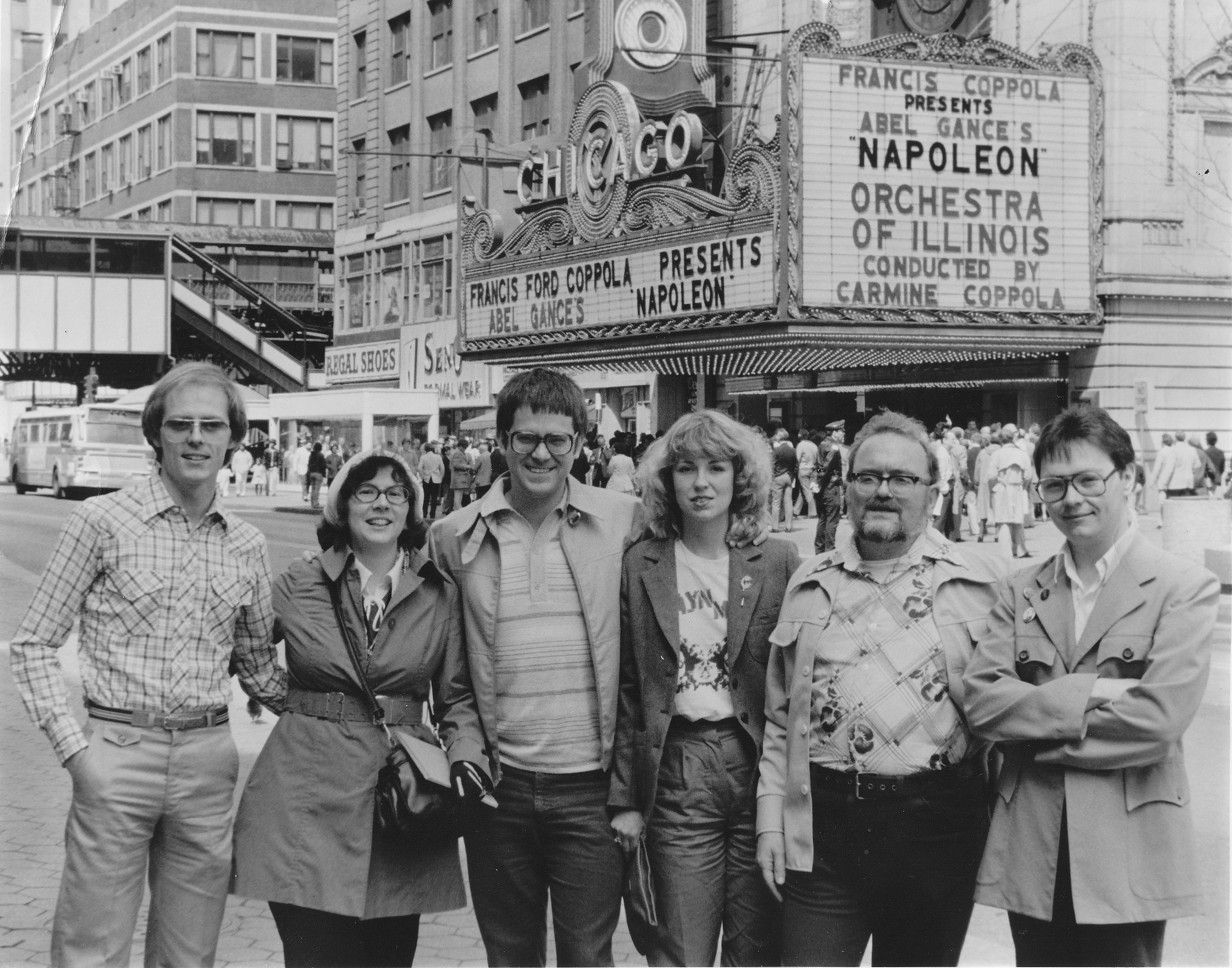

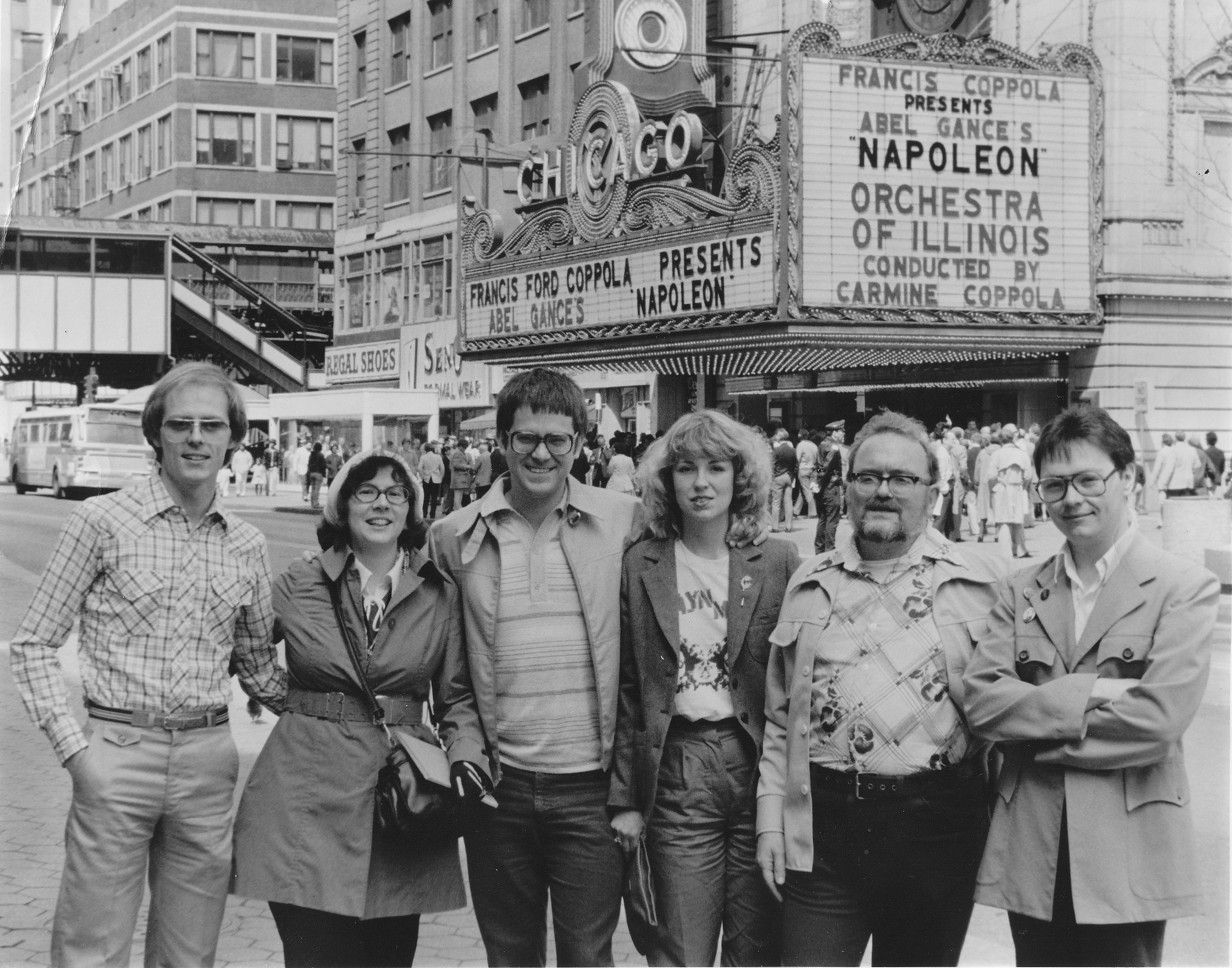

Brownlow's 1980 reconstruction was re-edited and released in the United States by

Brownlow's 1980 reconstruction was re-edited and released in the United States by American Zoetrope

American Zoetrope (also known as Omni Zoetrope from 1977 to 1980 and Zoetrope Studios from 1980 until 1990) is a privately run American film production company, centered in San Francisco, California and founded by Francis Ford Coppola and Georg ...

(through Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

) with a score by Carmine Coppola

Carmine Valentino Coppola (; June 11, 1910 – April 26, 1991) was an American composer, flautist, pianist, and songwriter who contributed original music to ''The Godfather'', ''The Godfather Part II'', ''Apocalypse Now'', '' The Outsiders'', an ...

performed live at the screenings. The restoration premiered in the United States at Radio City Music Hall

Radio City Music Hall is an entertainment venue and Theater (structure), theater at 1260 Sixth Avenue (Manhattan), Avenue of the Americas, within Rockefeller Center, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Nicknamed "The Showplac ...

in New York City on 23–25 January 1981; each performance showed to a standing room only

An event is described as standing-room only when it is so well-attended that all of the chairs in the venue are occupied, leaving only flat spaces of pavement or flooring for other attendees to stand, at least those spaces not restricted by occup ...

house. Gance could not attend because of poor health. At the end of 24 January screening, a telephone was brought onstage and the audience was told that Gance was listening on the other end and wished to know what they had thought of his film. The audience erupted in an ovation of applause and cheers that lasted several minutes. The acclaim surrounding the film's revival brought Gance much-belated recognition as a master director before his death eleven months later, in November 1981.

Another restoration was made by Brownlow in 1983. When it was screened at the Barbican Centre

The Barbican Centre is a performing arts centre in the Barbican Estate of the City of London and the largest of its kind in Europe. The centre hosts classical and contemporary music concerts, theatre performances, film screenings and art exhi ...

in London, French actress Annabella

Annabella, Anabella, or Anabela is a feminine given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Annabella of Scotland (c. 1433–1509), daughter of King James I

*Annabella (actress) (1907–1996), stage name of French actress Suzanne Georgette C ...

, who plays the fictional character Violine in the film (personifying France in her plight, beset by enemies from within and without), was in attendance. She was introduced to the audience prior to screenings and during one of the intervals sat alongside Kevin Brownlow, signing copies of the latter's book about the history and restoration of the film.

Brownlow re-edited the film again in 2000, including previously missing footage rediscovered by the Cinémathèque Française

The Cinémathèque Française (), founded in 1936, is a French non-profit film organization that holds one of the largest archives of film documents and film-related objects in the world. Based in Paris's 12th arrondissement, the archive offers ...

in Paris. Altogether, 35 minutes of reclaimed film had been added, making the total film length of the 2000 restoration five and a half hours.

The film is properly screened in full restoration very rarely due to the expense of the orchestra and the difficult requirement of three synchronised projectors and three screens for the Polyvision section. One such screening was at the Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

in London in December 2004, including a live orchestral score of classical music extracts arranged and conducted by Carl Davis

Carl Davis, (born October 28, 1936) is an American-born conductor and composer who has lived in the United Kingdom since 1961.

He has written music for more than 100 television programmes, but is best known for creating music to accompany si ...

. The screening itself was the subject of hotly contested legal threats from Francis Ford Coppola

Francis Ford Coppola (; ; born April 7, 1939) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter. He is considered one of the major figures of the New Hollywood filmmaking movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Coppola is the recipient of five A ...

via Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

to the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

over whether the latter had the right to screen the film without the Coppola score. An understanding was reached and the film was screened for both days. Coppola's single-screen version of the film was last projected for the public at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is an art museum located on Wilshire Boulevard in the Miracle Mile, Los Angeles, California, Miracle Mile vicinity of Los Angeles. LACMA is on Museum Row, adjacent to the La Brea Tar Pits (George C. Pa ...

in two showings in celebration of Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In French, it is formally called the (; "French National Celebration"); legally it is known as (; "t ...

on 13–14 July 2007, using a 70 mm print struck by Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

in the early 1980s.

At the San Francisco Silent Film Festival

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival is a film festival first held in 1996 and presented annually at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, California, United States. It is the largest silent film festival in the United States, although the largest ...

in July 2011, Brownlow announced there would be four screenings of his 2000 version, shown at the original 20 frames per second, with the final triptych and a live orchestra, to be held at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

, from 24 March to 1 April 2012. These, the first US screenings of his 5.5-hour-long restoration were described as requiring 3 intermissions, one of which was a dinner break. Score arranger Carl Davis led the 46-piece Oakland East Bay Symphony

The Oakland East Bay Symphony (OEBS) is a leading orchestra based in Oakland, California. Michael Morgan held the position of music director and conductor from September 1990 until his death in August 2021. The Paramount Theatre has been the hom ...

for the performances.

At a screening of ''Napoleon'' on 30 November 2013, at the Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

in London, full to capacity, the film and orchestra received a standing ovation, without pause, from the front of the stalls to the rear of the balcony. Davis conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra in a performance that spanned a little over eight hours, including a 100-minute dinner break.

On 13 November 2016, ''Napolėon'' was the subject of the ''Film Programme'' on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

. The BBC website announced: "Historian Kevin Brownlow tells Francine Stock

Francine Stock is a British radio and television presenter

A television presenter (or television host, some become a "television personality") is a person who introduces, hosts television show, television programs, often serving as a mediator ...

about his 50-year quest to restore Abel Gance's silent masterpiece Napoleon to its five and half-hour glory, and why the search for missing scenes still continues even though the film is about to be released on DVD for the very first time."

A restoration of the almost-seven-hour-long so-called Apollo version (i.e. the version of ''Napoléon'' shown at the Apollo Theatre in Paris in 1927), conducted by Cinémathèque Française

The Cinémathèque Française (), founded in 1936, is a French non-profit film organization that holds one of the largest archives of film documents and film-related objects in the world. Based in Paris's 12th arrondissement, the archive offers ...

under the direction of the restorer and director Georges Mourier, and financed by the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

along with Netflix

Netflix, Inc. is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service and production company based in Los Gatos, California. Founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in Scotts Valley, California, it offers a fil ...

, was scheduled to be completed by 5 May 2021. Because of complications associated with the restoration process, the release was postponed to 2023.

Reception

''Napoleon'' is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most innovative films of the silent era and of all time. Review aggregatorRotten Tomatoes

Rotten Tomatoes is an American review-aggregation website for film and television. The company was launched in August 1998 by three undergraduate students at the University of California, Berkeley: Senh Duong, Patrick Y. Lee, and Stephen Wang ...

reports that 88% of critics have given the film a positive review, based upon 40 reviews, with an average score of 9.6/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "Monumental in scale and distinguished by innovative technique, ''Napoléon'' is an expressive epic that maintains a singular intimacy with its subject."

Anita Brookner of ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published twice monthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of ...

'' wrote that the film has an "energy, extravagance, ambition, orgiastic pleasure, high drama and the desire for endless victory: not only Napoleon’s destiny but everyone’s most central hope." The 2012 screening has been acclaimed, with Mick LaSalle

Mick is a masculine given name, usually a short form (hypocorism) of Michael. Because of its popularity in Ireland, it is often used in England as a derogatory term for an Irish person or a person of Irish descent. In Australia the meaning broaden ...

of the ''San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and M. H. de Young, Michael H. de ...

'' calling the film, "A rich feast of images and emotions." He also praised the triptych finale, calling it, "An overwhelming and surprisingly emotional experience." Judith Martin of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' wrote that the movie "inspires that wonderfully satisfying theatrical experience of whole-heartedly cheering a hero and hissing villains, while also providing the uplift that comes from a real work of art" and praised its visual metaphors, editing, and tableaus. Peter Bradshaw

Peter Bradshaw (born 19 June 1962) is a British writer and film critic. He has been chief film critic at ''The Guardian'' since 1999, and is a contributing editor at ''Esquire''.

Early life and education

Bradshaw was educated at Haberdashers ...

wrote in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' that ''Napoleon'' "looks startlingly futuristic and experimental, as if we are being shown something from the 21st century’s bleeding edge. It’s as if it has evolved beyond spoken dialogue into some colossal mute hallucination." Mark Kermode

Mark James Patrick Kermode (, ; ; born 2 July 1963) is an English film critic, musician, radio presenter, television presenter and podcaster. He is the chief film critic for ''The Observer'', contributes to the magazine ''Sight & Sound'', prese ...

described the film "as significant to the evolution of cinema as the works of Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein (russian: Сергей Михайлович Эйзенштейн, p=sʲɪrˈɡʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ ɪjzʲɪnˈʂtʲejn, 2=Sergey Mikhaylovich Eyzenshteyn; 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenw ...

and D. W. Griffith