Namibian War of Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in

SWAPO leaders soon went abroad to mobilise support for their goals within the international community and newly independent African states in particular. The movement scored a major diplomatic success when it was recognised by

SWAPO leaders soon went abroad to mobilise support for their goals within the international community and newly independent African states in particular. The movement scored a major diplomatic success when it was recognised by

The advent of global

The advent of global

To regain the military initiative, the adoption of mine warfare as an integral strategy of PLAN was discussed at a 1969–70 SWAPO consultative congress held in Tanzania. PLAN's leadership backed the initiative to deploy land mines as a means of compensating for its inferiority in most conventional aspects to the South African security forces. Shortly afterwards, PLAN began acquiring

To regain the military initiative, the adoption of mine warfare as an integral strategy of PLAN was discussed at a 1969–70 SWAPO consultative congress held in Tanzania. PLAN's leadership backed the initiative to deploy land mines as a means of compensating for its inferiority in most conventional aspects to the South African security forces. Shortly afterwards, PLAN began acquiring

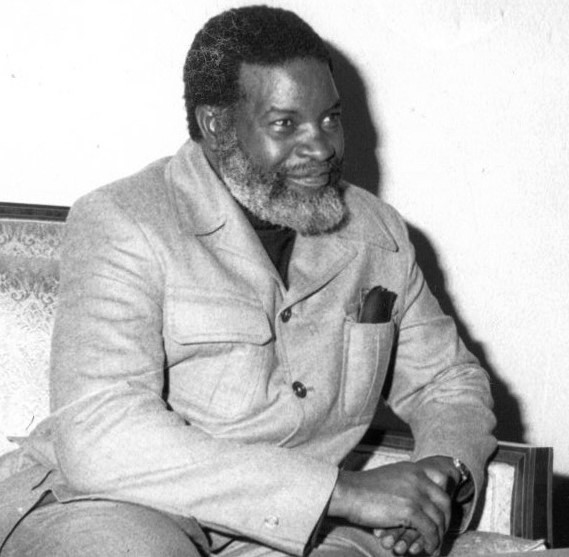

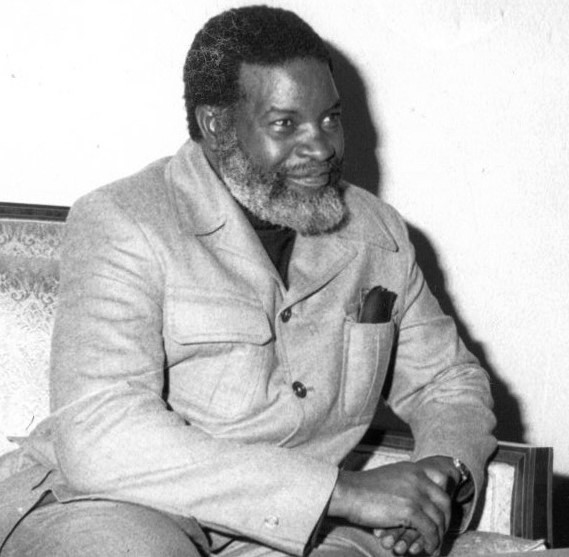

South Africa blamed SWAPO for instigating the strike and subsequent unrest. While acknowledging that a significant percentage of the strikers were SWAPO members and supporters, the party's acting president Nathaniel Maxuilili noted that reform of South West African labour laws had been a longstanding aspiration of the Ovambo workforce, and suggested the strike had been organised shortly after the crucial ICJ ruling because they hoped to take advantage of its publicity to draw greater attention to their grievances. The strike also had a politicising effect on much of the Ovambo population, as the workers involved later turned to wider political activity and joined SWAPO. Around 20,000 strikers did not return to work but fled to other countries, mostly Zambia, where some were recruited as guerrillas by PLAN. Support for PLAN also increased among the rural Ovamboland peasantry, who were for the most part sympathetic with the strikers and resentful of their traditional chiefs' active collaboration with the police.

The following year, South Africa transferred self-governing authority to Chief Fillemon Elifas Shuumbwa and the Ovambo legislature, effectively granting Ovamboland a limited form of

South Africa blamed SWAPO for instigating the strike and subsequent unrest. While acknowledging that a significant percentage of the strikers were SWAPO members and supporters, the party's acting president Nathaniel Maxuilili noted that reform of South West African labour laws had been a longstanding aspiration of the Ovambo workforce, and suggested the strike had been organised shortly after the crucial ICJ ruling because they hoped to take advantage of its publicity to draw greater attention to their grievances. The strike also had a politicising effect on much of the Ovambo population, as the workers involved later turned to wider political activity and joined SWAPO. Around 20,000 strikers did not return to work but fled to other countries, mostly Zambia, where some were recruited as guerrillas by PLAN. Support for PLAN also increased among the rural Ovamboland peasantry, who were for the most part sympathetic with the strikers and resentful of their traditional chiefs' active collaboration with the police.

The following year, South Africa transferred self-governing authority to Chief Fillemon Elifas Shuumbwa and the Ovambo legislature, effectively granting Ovamboland a limited form of

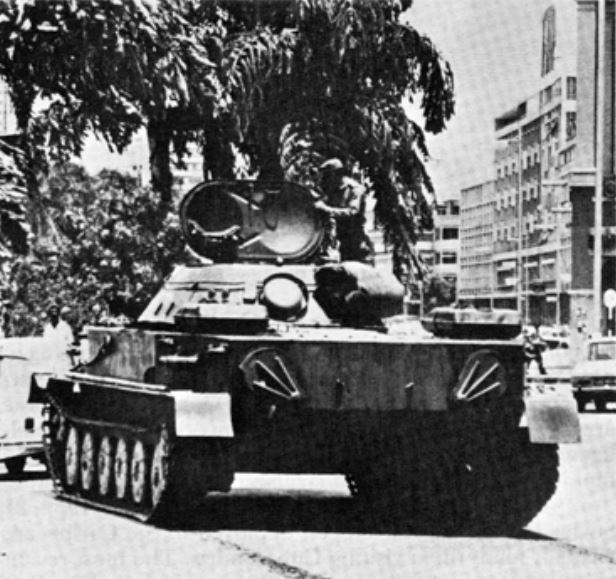

A watershed in the Angolan conflict was the South African decision on 25 October to commit 2,500 of its own troops to battle. Larger quantities of more sophisticated arms had been delivered to FAPLA by this point, such as T-34-85 tanks, wheeled armoured personnel carriers, towed rocket launchers and field guns. While most of this hardware was antiquated, it proved extremely effective, given the fact that most of FAPLA's opponents consisted of disorganised, under-equipped militias. In early October, FAPLA launched a major combined arms offensive on UNITA's national headquarters at Nova Lisboa, which was only repelled with considerable difficulty and assistance from a small team of SADF advisers. It became evident to the SADF that neither UNITA or the FNLA possessed armies capable of taking and holding territory, as their fighting strength depended on militias which excelled only in guerrilla warfare. South Africa would need its own combat troops to not only defend its allies, but carry out a decisive counter-offensive against FAPLA. This proposal was approved by the South African government on the condition that only a small, covert task force would be permitted. SADF personnel participating in offensive operations were told to pose as mercenaries. They were stripped of any identifiable equipment, including their

A watershed in the Angolan conflict was the South African decision on 25 October to commit 2,500 of its own troops to battle. Larger quantities of more sophisticated arms had been delivered to FAPLA by this point, such as T-34-85 tanks, wheeled armoured personnel carriers, towed rocket launchers and field guns. While most of this hardware was antiquated, it proved extremely effective, given the fact that most of FAPLA's opponents consisted of disorganised, under-equipped militias. In early October, FAPLA launched a major combined arms offensive on UNITA's national headquarters at Nova Lisboa, which was only repelled with considerable difficulty and assistance from a small team of SADF advisers. It became evident to the SADF that neither UNITA or the FNLA possessed armies capable of taking and holding territory, as their fighting strength depended on militias which excelled only in guerrilla warfare. South Africa would need its own combat troops to not only defend its allies, but carry out a decisive counter-offensive against FAPLA. This proposal was approved by the South African government on the condition that only a small, covert task force would be permitted. SADF personnel participating in offensive operations were told to pose as mercenaries. They were stripped of any identifiable equipment, including their

Throughout late November and early December, the Cubans focused on fighting the FNLA in the north, and stopping an abortive incursion by

Throughout late November and early December, the Cubans focused on fighting the FNLA in the north, and stopping an abortive incursion by

Operation Savannah accelerated the shift of SWAPO's alliances among the Angolan nationalist movements. Until August 1975, SWAPO was theoretically aligned with the MPLA, but in reality PLAN had enjoyed a close working relationship with UNITA during the Angolan War of Independence. In September 1975, SWAPO issued a public statement declaring its intention to remain neutral in the Angolan Civil War and refrain from supporting any single political faction or party. With the South African withdrawal in March, Sam Nujoma retracted his movement's earlier position and endorsed the MPLA as the "authentic representative of the Angolan people". During the same month, Cuba began flying in small numbers of PLAN recruits from Zambia to Angola to commence guerrilla training. PLAN shared intelligence with the Cubans and FAPLA, and from April 1976 even fought alongside them against UNITA. FAPLA often used PLAN cadres to garrison strategic sites while freeing up more of its own personnel for deployments elsewhere.

The emerging MPLA-SWAPO alliance took on special significance after the latter movement was wracked by factionalism and a series of PLAN mutinies in

Operation Savannah accelerated the shift of SWAPO's alliances among the Angolan nationalist movements. Until August 1975, SWAPO was theoretically aligned with the MPLA, but in reality PLAN had enjoyed a close working relationship with UNITA during the Angolan War of Independence. In September 1975, SWAPO issued a public statement declaring its intention to remain neutral in the Angolan Civil War and refrain from supporting any single political faction or party. With the South African withdrawal in March, Sam Nujoma retracted his movement's earlier position and endorsed the MPLA as the "authentic representative of the Angolan people". During the same month, Cuba began flying in small numbers of PLAN recruits from Zambia to Angola to commence guerrilla training. PLAN shared intelligence with the Cubans and FAPLA, and from April 1976 even fought alongside them against UNITA. FAPLA often used PLAN cadres to garrison strategic sites while freeing up more of its own personnel for deployments elsewhere.

The emerging MPLA-SWAPO alliance took on special significance after the latter movement was wracked by factionalism and a series of PLAN mutinies in

Access to Angola provided PLAN with limitless opportunities to train its forces in secure sanctuaries and infiltrate insurgents and supplies across South West Africa's northern border. The guerrillas gained a great deal of leeway to manage their logistical operations through Angola's Moçâmedes District, using the ports, roads, and railways from the sea to supply their forward operating bases. Soviet vessels offloaded arms at the port of Moçâmedes, which were then transshipped by rail to Lubango and from there through a chain of PLAN supply routes snaking their way south towards the border. "Our geographic isolation was over," Nujoma commented in his memoirs. "It was as if a locked door had suddenly swung open...we could at last make direct attacks across our northern frontier and send in our forces and weapons on a large scale."

In the territories of Ovamboland, Kaokoland, Kavangoland and East Caprivi after 1976, the SADF installed fixed defences against infiltration, employing two parallel electrified fences and motion sensors. The system was backed by roving patrols drawn from Eland armoured car squadrons, motorised infantry, canine units, horsemen and scrambler motorcycles for mobility and speed over rough terrain; local San trackers, Ovambo paramilitaries, and South African special forces. PLAN attempted hit-and-run raids across the border but, in what was characterised as the "corporal's war", SADF sections largely intercepted them in the Cutline before they could get any further into South West Africa itself. The brunt of the fighting was shouldered by small, mobile rapid reaction forces, whose role was to track and eliminate the insurgents after a PLAN presence was detected. These reaction forces were attached on the battalion level and maintained at maximum readiness on individual bases.

The SADF carried out mostly reconnaissance operations inside Angola, although its forces in South West Africa could fire and manoeuvre across the border in self-defence if attacked from the Angolan side. Once they reached the Cutline, a reaction force sought permission either to enter Angola or abort the pursuit. South Africa also set up a specialist unit, 32 Battalion, which concerned itself with reconnoitring infiltration routes from Angola. 32 Battalion regularly sent teams recruited from ex-FNLA militants and led by white South African personnel into an authorised zone up to fifty kilometres deep in Angola; it could also dispatch platoon-sized reaction forces of similar composition to attack vulnerable PLAN targets. As their operations had to be clandestine and covert, with no link to South African forces, 32 Battalion teams wore FAPLA or PLAN uniforms and carried Soviet weapons.

Climate shaped the activities of both sides. Seasonal variations during the summer passage of the Intertropical Convergence Zone resulted in an annual period of heavy rains over northern South West Africa between February and April. The rainy season made military operations difficult. Thickening foliage provided the insurgents with concealment from South African patrols, and their tracks were obliterated by the rain. At the end of April or early May, PLAN cadres returned to Angola to escape renewed SADF

Access to Angola provided PLAN with limitless opportunities to train its forces in secure sanctuaries and infiltrate insurgents and supplies across South West Africa's northern border. The guerrillas gained a great deal of leeway to manage their logistical operations through Angola's Moçâmedes District, using the ports, roads, and railways from the sea to supply their forward operating bases. Soviet vessels offloaded arms at the port of Moçâmedes, which were then transshipped by rail to Lubango and from there through a chain of PLAN supply routes snaking their way south towards the border. "Our geographic isolation was over," Nujoma commented in his memoirs. "It was as if a locked door had suddenly swung open...we could at last make direct attacks across our northern frontier and send in our forces and weapons on a large scale."

In the territories of Ovamboland, Kaokoland, Kavangoland and East Caprivi after 1976, the SADF installed fixed defences against infiltration, employing two parallel electrified fences and motion sensors. The system was backed by roving patrols drawn from Eland armoured car squadrons, motorised infantry, canine units, horsemen and scrambler motorcycles for mobility and speed over rough terrain; local San trackers, Ovambo paramilitaries, and South African special forces. PLAN attempted hit-and-run raids across the border but, in what was characterised as the "corporal's war", SADF sections largely intercepted them in the Cutline before they could get any further into South West Africa itself. The brunt of the fighting was shouldered by small, mobile rapid reaction forces, whose role was to track and eliminate the insurgents after a PLAN presence was detected. These reaction forces were attached on the battalion level and maintained at maximum readiness on individual bases.

The SADF carried out mostly reconnaissance operations inside Angola, although its forces in South West Africa could fire and manoeuvre across the border in self-defence if attacked from the Angolan side. Once they reached the Cutline, a reaction force sought permission either to enter Angola or abort the pursuit. South Africa also set up a specialist unit, 32 Battalion, which concerned itself with reconnoitring infiltration routes from Angola. 32 Battalion regularly sent teams recruited from ex-FNLA militants and led by white South African personnel into an authorised zone up to fifty kilometres deep in Angola; it could also dispatch platoon-sized reaction forces of similar composition to attack vulnerable PLAN targets. As their operations had to be clandestine and covert, with no link to South African forces, 32 Battalion teams wore FAPLA or PLAN uniforms and carried Soviet weapons.

Climate shaped the activities of both sides. Seasonal variations during the summer passage of the Intertropical Convergence Zone resulted in an annual period of heavy rains over northern South West Africa between February and April. The rainy season made military operations difficult. Thickening foliage provided the insurgents with concealment from South African patrols, and their tracks were obliterated by the rain. At the end of April or early May, PLAN cadres returned to Angola to escape renewed SADF  Unharried by major South African offensives, PLAN was free to consolidate its military organisation in Angola. PLAN's leadership under Dimo Hamaambo concentrated on improving its communications and control throughout that country, demarcating the Angolan front into three military zones, in which guerrilla activities were coordinated by a single operational headquarters. The Western Command was headquartered in western

Unharried by major South African offensives, PLAN was free to consolidate its military organisation in Angola. PLAN's leadership under Dimo Hamaambo concentrated on improving its communications and control throughout that country, demarcating the Angolan front into three military zones, in which guerrilla activities were coordinated by a single operational headquarters. The Western Command was headquartered in western

An adjacent Cuban mechanised infantry battalion stationed sixteen kilometres to the south advanced to confront the paratroops during the attack, but suffered several delays due to strafing runs by South African

An adjacent Cuban mechanised infantry battalion stationed sixteen kilometres to the south advanced to confront the paratroops during the attack, but suffered several delays due to strafing runs by South African

Defence chiefs such as General

Defence chiefs such as General  US–South African relations took an unexpected turn with Ronald Reagan's electoral victory in the 1980 US presidential elections. Reagan's tough anti-communist record and rhetoric was greeted with cautious optimism by Pretoria; during his election campaign he'd described the geopolitical situation in southern Africa as "a Russian weapon" aimed at the US. President Reagan and his Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester Crocker adopted a policy of constructive engagement with the Botha government, restored military attachés to the US embassy in South Africa, and permitted SADF officers to receive technical training in the US. They believed that pressure tactics against South Africa would be contrary to US regional goals, namely countering Soviet and Cuban influence. In a private memo addressed to the South African foreign minister, Crocker and his supervisor

US–South African relations took an unexpected turn with Ronald Reagan's electoral victory in the 1980 US presidential elections. Reagan's tough anti-communist record and rhetoric was greeted with cautious optimism by Pretoria; during his election campaign he'd described the geopolitical situation in southern Africa as "a Russian weapon" aimed at the US. President Reagan and his Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester Crocker adopted a policy of constructive engagement with the Botha government, restored military attachés to the US embassy in South Africa, and permitted SADF officers to receive technical training in the US. They believed that pressure tactics against South Africa would be contrary to US regional goals, namely countering Soviet and Cuban influence. In a private memo addressed to the South African foreign minister, Crocker and his supervisor

Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

(then South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

), Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, and Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

from 26 August 1966 to 21 March 1990. It was fought between the South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF) and the People's Liberation Army of Namibia

The People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) was the military wing of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO). It fought against the South African Defence Force (SADF) and South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) during the Sou ...

(PLAN), an armed wing of the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO). The South African Border War resulted in some of the largest battles on the African continent since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and was closely intertwined with the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war was ...

.

Following several years of unsuccessful petitioning through the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

and the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

for Namibian independence from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, SWAPO formed the PLAN in 1962 with material assistance from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, China, and sympathetic African states such as Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

, Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. Fighting broke out between PLAN and the South African authorities in August 1966. Between 1975 and 1988 the SADF staged massive conventional raids into Angola and Zambia to eliminate PLAN's forward operating base

A forward operating base (FOB) is any secured forward operational level military position, commonly a military base, that is used to support strategic goals and tactical objectives. A FOB may or may not contain an airfield, hospital, machine ...

s. It also deployed specialist counter-insurgency units such as ''Koevoet

Koevoet (, meaning ''crowbar'', also known as Operation K or SWAPOL-COIN) was the counterinsurgency branch of the South West African Police (SWAPOL). Its formations included white South African police officers, usually seconded from the South A ...

'' and 32 Battalion, trained to carry out external reconnaissance and track guerrilla movements.

South African tactics became increasingly aggressive as the conflict progressed. The SADF's incursions produced Angolan casualties and occasionally resulted in severe collateral damage to economic installations regarded as vital to the Angolan economy. Ostensibly to stop these raids, but also to disrupt the growing alliance between the SADF and the National Union for the Total Independence for Angola (UNITA), which the former was arming with captured PLAN equipment, the Soviet Union backed the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola

The People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola ( pt, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola) or FAPLA was originally the armed wing of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) but later (1975–1991) became Ango ...

(FAPLA) through a large contingent of military advisers and up to four billion dollars' worth of modern defence technology in the 1980s. Beginning in 1984, regular Angolan units under Soviet command were confident enough to confront the SADF. Their positions were also bolstered by thousands of Cuban troops. The state of war between South Africa and Angola briefly ended with the short-lived Lusaka Accords, but resumed in August 1985 as both PLAN and UNITA took advantage of the ceasefire to intensify their own guerrilla activity, leading to a renewed phase of FAPLA combat operations culminating in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale was fought intermittently between 14 August 1987 and 23 March 1988, south and east of the town of Cuito Cuanavale, Angola, by the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and advisors and sold ...

. The South African Border War was virtually ended by the Tripartite Accord, mediated by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, which committed to a withdrawal of Cuban and South African military personnel from Angola and South West Africa, respectively. PLAN launched its final guerrilla campaign in April 1989. South West Africa received formal independence as the Republic of Namibia a year later, on 21 March 1990.

Despite being largely fought in neighbouring states, the South African Border War had a phenomenal cultural and political impact on South African society. The country's apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

government devoted considerable effort towards presenting the war as part of a containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

programme against regional Soviet expansionism and used it to stoke public anti-communist sentiment. It remains an integral theme in contemporary South African literature at large and Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

-language works in particular, having given rise to a unique genre known as ''grensliteratuur'' (directly translated "border literature").

Nomenclature

Various names have been applied to the undeclared conflict waged by South Africa inAngola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

and Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

(then South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

) from the mid 1960s to the late 1980s. The term "South African Border War" has typically denoted the military campaign launched by the People's Liberation Army of Namibia

The People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) was the military wing of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO). It fought against the South African Defence Force (SADF) and South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) during the Sou ...

(PLAN), which took the form of sabotage and rural insurgency, as well as the external raids launched by South African troops on suspected PLAN bases inside Angola or Zambia, sometimes involving major conventional warfare against the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola

The People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola ( pt, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola) or FAPLA was originally the armed wing of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) but later (1975–1991) became Ango ...

(FAPLA) and its Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

n allies. The strategic situation was further complicated by the fact that South Africa occupied large swathes of Angola for extended periods in support of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

(UNITA), making the "Border War" an increasingly inseparable conflict from the parallel Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war was ...

.

"Border War" entered public discourse in South Africa during the late 1970s, and was adopted thereafter by the country's ruling National Party. Due to the covert nature of most South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF) operations inside Angola, the term was favoured as a means of omitting any reference to clashes on foreign soil. Where tactical aspects of various engagements were discussed, military historians simply identified the conflict as the "bush war".

The South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) has described the South African Border War as the Namibian War of National Liberation and the Namibian Liberation Struggle. In the Namibian context, it is also commonly referred to as the Namibian War of Independence. However, these terms have been criticised for ignoring the wider regional implications of the war and the fact that PLAN was based in, and did most of its fighting from, countries other than Namibia.

Background

Namibia was governed asGerman South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

, a colony of the German Empire, until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when it was invaded and occupied by Allied forces under General Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, ...

. Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

, a mandate system

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

was imposed by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

to govern African and Asian territories held by Germany and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

prior to the war. The mandate system was formed as a compromise between those who advocated an Allied annexation of former German and Turkish territories, and another proposition put forward by those who wished to grant them to an international trusteeship until they could govern themselves.

All former German and Turkish territories were classified into three types of mandates – Class "A" mandates, predominantly in the Middle East, Class "B" mandates, which encompassed central Africa, and Class "C" mandates, which were reserved for the most sparsely populated or least developed German colonies: South West Africa, German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

, and the Pacific islands.

Owing to their small size, geographic remoteness, low population density, or physical contiguity to the mandatory itself, Class "C" mandates could be administered as integral provinces of the countries to which they were entrusted. Nevertheless, the bestowal of a mandate by the League of Nations did not confer full sovereignty, only the responsibility of administering it. In principle, mandating countries were only supposed to hold these former colonies "in trust" for their inhabitants, until they were sufficiently prepared for their own self-determination. Under these terms, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand were granted the German Pacific islands, and the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

received South West Africa.

It soon became apparent the South African government had interpreted the mandate as a veiled annexation. In September 1922, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

testified before the League of Nations Mandate Commission that South West Africa was being fully incorporated into the Union and should be regarded, for all practical purposes, as a fifth province of South Africa. According to Smuts, this constituted "annexation in all but in name".

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the League of Nations complained that of all the mandatory powers South Africa was the most delinquent with regards to observing the terms of its mandate. The Mandate Commission vetoed a number of ambitious South African policy decisions, such as proposals to nationalise South West African railways or alter the preexisting borders. Sharp criticism was also leveled at South Africa's disproportionate spending on the local white population, which the former defended as obligatory since white South West Africans were taxed the heaviest. The League adopted the argument that no one segment of any mandate's population was entitled to favourable treatment over another, and the terms under which the mandate had been granted made no provision for special obligation towards whites. It pointed out that there was little evidence of progress being made towards political self-determination; just prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

South Africa and the League remained at an impasse over this dispute.

Legality of South West Africa, 1946–1960

After World War II, Jan Smuts headed the South African delegation to theUnited Nations Conference on International Organization

The United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), commonly known as the San Francisco Conference, was a convention of delegates from 50 Allied nations that took place from 25 April 1945 to 26 June 1945 in San Francisco, Cali ...

. As a result of this conference, the League of Nations was formally superseded by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

(UN) and former League mandates by a trusteeship system. Article 77 of the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

stated that UN trusteeship "shall apply...to territories now held under mandate"; furthermore, it would "be a matter of subsequent agreement as to which territories in the foregoing territories will be brought under the trusteeship system and under what terms". Smuts was suspicious of the proposed trusteeship, largely because of the vague terminology in Article 77.

Heaton Nicholls, the South African high commissioner in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and a member of the Smuts delegation to the UN, addressed the newly formed UN General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presb ...

on 17 January 1946. Nicholls stated that the legal uncertainty of South West Africa's situation was retarding development and discouraging foreign investment; however, self-determination for the time being was impossible since the territory was too undeveloped and underpopulated to function as a strong independent state. In the second part of the first session of the General Assembly, the floor was handed to Smuts, who declared that the mandate was essentially a part of the South African territory and people. Smuts informed the General Assembly that it had already been so thoroughly incorporated with South Africa a UN-sanctioned annexation was no more than a necessary formality.

The Smuts delegation's request for the termination of the mandate and permission to annex South West Africa was not well received by the General Assembly. Five other countries, including three major colonial powers, had agreed to place their mandates under the trusteeship of the UN, at least in principle; South Africa alone refused. Most delegates insisted it was undesirable to endorse the annexation of a mandated territory, especially when all of the others had entered trusteeship. Thirty-seven member states voted to block a South African annexation of South West Africa; nine abstained.

In Pretoria, right-wing politicians reacted with outrage at what they perceived as unwarranted UN interference in the South West Africa affair. The National Party dismissed the UN as unfit to meddle with South Africa's policies or discuss its administration of the mandate. One National Party speaker, Eric Louw

Eric Hendrik Louw (1890–1968) was a South African diplomat and politician. He served as the Minister of Finance from 1954 to 1956, and as the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1955 to 1963.

Early life

He was born in Jacobsdal in the Orange Fr ...

, demanded that South West Africa be annexed unilaterally. During the South African general election, 1948

General elections were held in South Africa on 26 May 1948. They represented a turning point in the country's history, as despite receiving just under half of the votes cast, the United Party and its leader, incumbent Prime Minister Jan Smuts, ...

, the National Party was swept into power, newly appointed Prime Minister Daniel Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

prepared to adopt a more aggressive stance concerning annexation, and Louw was named ambassador to the UN. During an address in Windhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 202 ...

, Malan reiterated his party's position that South Africa would annex the mandate before surrendering it to an international trusteeship. The following year a formal statement was issued to the General Assembly which proclaimed that South Africa had no intention of complying with trusteeship, nor was it obligated to release new information or reports pertaining to its administration. Simultaneously, the South West Africa Affairs Administration Act, 1949, was passed by South African parliament. The new legislation gave white South West Africans parliamentary representation and the same political rights as white South Africans.

The UN General Assembly responded by deferring to the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

(ICJ), which was to issue an advisory opinion on the international status of South West Africa. The ICJ ruled that South West Africa was still being governed as a mandate; hence, South Africa was not legally obligated to surrender it to the UN trusteeship system if it did not recognise the mandate system had lapsed, conversely, however, it was still bound by the provisions of the original mandate. Adherence to these provisions meant South Africa was not empowered to unilaterally modify the international status of South West Africa. Malan and his government rejected the court's opinion as irrelevant. The UN formed a Committee on South West Africa, which issued its own independent reports regarding the administration and development of that territory. The Committee's reports became increasingly scathing of South African officials when the National Party imposed its harsh system of racial segregation and stratification—''apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

''—on South West Africa.

In 1958, the UN established a Good Offices Committee which continued to invite South Africa to bring South West Africa under trusteeship. The Good Offices Committee proposed a partition of the mandate, allowing South Africa to annex the southern portion while either granting independence to the north, including the densely populated Ovamboland region, or administering it as an international trust territory. The proposal met with overwhelming opposition in the General Assembly; fifty-six nations voted against it. Any further partition of South West Africa was rejected out of hand.

Internal opposition to South African rule

Mounting internal opposition to apartheid played an instrumental role in the development and militancy of a South West African nationalist movement throughout the mid to late 1950s. The 1952Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa in December 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conference. The demonstrations, ...

, a series of nonviolent protests launched by the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

against pass laws

In South Africa, pass laws were a form of internal passport system designed to segregate the population, manage urbanization and allocate migrant labor. Also known as the natives' law, pass laws severely limited the movements of not only black ...

, inspired the formation of South West African student unions opposed to apartheid. In 1955, their members organised the South West African Progressive Association (SWAPA), chaired by Uatja Kaukuetu, to campaign for South West African independence. Although SWAPA did not garner widespread support beyond intellectual circles, it was the first nationalist body claiming to support the interests of all black South West Africans, irrespective of tribe or language. SWAPA's activists were predominantly Herero students, schoolteachers, and other members of the emerging black intelligentsia in Windhoek. Meanwhile, the Ovamboland People's Congress (later the ''Ovamboland People's Organisation'', or OPO) was formed by nationalists among partly urbanised migrant Ovambo labourers in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. The OPO's constitution cited the achievement of a UN trusteeship and ultimate South West African independence as its primary goals. A unified movement was proposed that would include the politicisation of Ovambo contract workers from northern South West Africa as well as the Herero students, which resulted in the unification of SWAPA and the OPO as the South West African National Union (SWANU) on 27 September 1959.

In December 1959, the South African government announced that it would forcibly relocate all residents of Old Location

The Old Location (or as it was known then the Main Location) was an area segregated for Black residents of Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. It was situated in the area between today's suburbs of Hochland Park and Pioneers Park.

History

Upon the ...

, a black neighbourhood located near Windhoek's city center, in accordance with apartheid legislation. SWANU responded by organising mass demonstrations and a bus boycott on 10 December, and in the ensuing confrontation South African police opened fire, killing eleven protestors. In the wake of the Old Location incident, the OPO split from SWANU, citing differences with the organisation's Herero leadership, then petitioning UN delegates in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. As the UN and potential foreign supporters reacted sensitively to any implications of tribalism and had favoured SWANU for its claim to represent the South West African people as a whole, the OPO was likewise rebranded the South West African People's Organisation. It later opened its ranks to all South West Africans sympathetic to its aims.

SWAPO leaders soon went abroad to mobilise support for their goals within the international community and newly independent African states in particular. The movement scored a major diplomatic success when it was recognised by

SWAPO leaders soon went abroad to mobilise support for their goals within the international community and newly independent African states in particular. The movement scored a major diplomatic success when it was recognised by Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

and allowed to open an office in Dar es Salaam. SWAPO's first manifesto, released in July 1960, was remarkably similar to SWANU's. Both advocated the abolition of colonialism and all forms of racialism, the promotion of Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

, and called for the "economic, social, and cultural advancement" of South West Africans. However, SWAPO went a step further by demanding immediate independence under black majority rule, to be granted at a date no later than 1963. The SWAPO manifesto also promised universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

, sweeping welfare programmes, free healthcare, free public education, the nationalisation of all major industry, and the forcible redistribution of foreign-owned land "in accordance with African communal ownership principles".

Compared to SWANU, SWAPO's potential for wielding political influence within South West Africa was limited, and it was likelier to accept armed insurrection as the primary means of achieving its goals accordingly. SWAPO leaders also argued that a decision to take up arms against the South Africans would demonstrate their superior commitment to the nationalist cause. This would also distinguish SWAPO from SWANU in the eyes of international supporters as the genuine vanguard of the Namibian independence struggle, and the legitimate recipient of any material assistance that was forthcoming. Modelled after Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress, the South West African Liberation Army (SWALA) was formed by SWAPO in 1962. The first seven SWALA recruits were sent from Dar es Salaam to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, where they received military instruction. Upon their return they began training guerrillas at a makeshift camp established for housing South West African refugees in Kongwa

Kongwa District is one of the seven districts of the Dodoma Region of Tanzania. It is bordered to the north by Manyara Region, to the east by Morogoro Region, to the south by Mpwapwa District, and to the west by Chamwino District. Its district ca ...

, Tanzania.

Cold War tensions and the border militarisation

The increasing likelihood of armed conflict in South West Africa had strong international foreign policy implications, for both Western Europe and the Soviet bloc. Prior to the late 1950s, South Africa's defence policy had been influenced by international Cold War politics, including thedomino theory

The domino theory is a geopolitical theory which posits that increases or decreases in democracy in one country tend to spread to neighboring countries in a domino effect. It was prominent in the United States from the 1950s to the 1980s in t ...

and fears of a conventional Soviet military threat to the strategic Cape trade route between the south Atlantic and Indian oceans. Noting that the country had become the world's principal source of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

, the South African Department of External Affairs reasoned that "on this account alone, therefore, South Africa is bound to be implicated in any war between East and West". Prime Minister Malan took the position that colonial Africa was being directly threatened by the Soviets, or at least by Soviet-backed communist agitation, and this was only likely to increase whatever the result of another European war. Malan promoted an African Pact, similar to NATO, headed by South Africa and the Western colonial powers accordingly. The concept failed due to international opposition to apartheid and suspicion of South African military overtures in the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

.

South Africa's involvement in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

produced a significant warming of relations between Malan and the United States, despite American criticism of apartheid. Until the early 1960s, South African strategic and military support was considered an integral component of U.S. foreign policy in Africa's southern subcontinent, and there was a steady flow of defence technology from Washington to Pretoria. American and Western European interest in the defence of Africa from a hypothetical, external communist invasion dissipated after it became clear that the nuclear arms race was making global conventional war increasingly less likely. Emphasis shifted towards preventing communist subversion and infiltration via proxy

Proxy may refer to:

* Proxy or agent (law), a substitute authorized to act for another entity or a document which authorizes the agent so to act

* Proxy (climate), a measured variable used to infer the value of a variable of interest in climate ...

rather than overt Soviet aggression.

decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

and the subsequent rise in prominence of the Soviet Union among several newly independent African states was viewed with wariness by the South African government. National Party politicians began warning it would only be a matter of time before they were faced with a Soviet-directed insurgency on their borders. Outlying regions in South West Africa, namely the Caprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is surrounded by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a s ...

, became the focus of massive SADF air and ground training manoeuvres, as well as heightened border patrols. A year before SWAPO made the decision to send its first SWALA recruits abroad for guerrilla training, South Africa established fortified police outposts along the Caprivi Strip for the express purpose of deterring insurgents. When SWALA cadres armed with Soviet weapons and training began to make their appearance in South West Africa, the National Party believed its fears of a local Soviet proxy force had finally been realised.

The Soviet Union took a keen interest in Africa's independence movements and initially hoped that the cultivation of socialist client states on the continent would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West. Soviet training of SWALA was thus not confined to tactical matters but extended to Marxist–Leninist political theory, and the procedures for establishing an effective political-military infrastructure. In addition to training, the Soviets quickly became SWALA's leading supplier of arms and money. Weapons supplied to SWALA between 1962 and 1966 included PPSh-41 submachine guns, SKS carbines, and TT-33

The TT-30,, "7.62 mm Tokarev self-loading pistol model 1930", TT stands for Tula-Tokarev) commonly known simply as the Tokarev, is an out-of-production Soviet semi-automatic pistol. It was developed in 1930 by Fedor Tokarev as a service pisto ...

pistols, which were well-suited to the insurgents' unconventional warfare strategy.

Despite its burgeoning relationship with SWAPO, the Soviet Union did not regard Southern Africa as a major strategic priority in the mid 1960s, due to its preoccupation elsewhere on the continent and in the Middle East. Nevertheless, the perception of South Africa as a regional Western ally and a bastion of neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, ...

helped fuel Soviet backing for the nationalist movement. Moscow also approved of SWAPO's decision to adopt guerrilla warfare because it was not optimistic about any solution to the South West Africa problem short of revolutionary struggle. This was in marked contrast to the Western governments, which opposed the formation of SWALA and turned down the latter's requests for military aid.

The insurgency begins, 1964–1974

Early guerrilla incursions

In November 1960,Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

and Liberia had formally petitioned the ICJ for a binding judgement, rather than an advisory opinion, on whether South Africa remained fit to govern South West Africa. Both nations made it clear that they considered the implementation of ''apartheid'' to be a violation of Pretoria's obligations as a mandatory power. The National Party government rejected the claim on the grounds that Ethiopia and Liberia lacked sufficient legal interest to present a case concerning South West Africa. This argument suffered a major setback on 21 December 1962 when the ICJ ruled that as former League of Nations member states, both parties had a right to institute the proceedings.

Around March 1962 SWAPO President Sam Nujoma

Samuel Shafiishuna Daniel Nujoma, (; born 12 May 1929) is a Namibian revolutionary, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served three terms as the first President of Namibia, from 1990 to 2005. Nujoma was a founding member and the first ...

visited the party's refugee camps across Tanzania, describing his recent petitions for South West African independence at the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

and the UN. He pointed out that independence was unlikely in the foreseeable future, predicting a "long and bitter struggle". Nujoma personally directed two exiles in Dar es Salaam, Lucas Pohamba and Elia Muatale, to return to South West Africa, infiltrate Ovamboland and send back more potential recruits for SWALA. Over the next few years Pohamba and Muatale successfully recruited hundreds of volunteers from the Ovamboland countryside, most of whom were shipped to Eastern Europe for guerrilla training. Between July 1962 and October 1963 SWAPO negotiated military alliances with other anti-colonial movements, namely in Angola. It also absorbed the separatist ''Caprivi African National Union'' (CANU), which was formed to combat South African rule in the Caprivi Strip. Outside the Soviet bloc, Egypt continued training SWALA personnel. By 1964 others were also being sent to Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

for military instruction. In June of that year, SWAPO confirmed that it was irrevocably committed to the course of armed revolution.

The formation of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

(OAU)'s Liberation Committee further strengthened SWAPO's international standing and ushered in an era of unprecedented political decline for SWANU. The Liberation Committee had obtained approximately £20,000 in obligatory contributions from OAU member states; these funds were offered to both South West African nationalist movements. However, as SWANU was unwilling to guarantee its share of the £20,000 would be used for armed struggle, this grant was awarded to SWAPO instead. The OAU then withdrew recognition from SWANU, leaving SWAPO as the sole beneficiary of pan-African legitimacy. With OAU assistance, SWAPO opened diplomatic offices in Lusaka, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

, and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. SWANU belatedly embarked on a ten-year programme to raise its own guerrilla army.

In September 1965, the first unit of six SWALA guerrillas, identified simply as ''"Group 1"'', departed the Kongwa refugee camp to infiltrate South West Africa. Group 1 trekked first into Angola, before crossing the border into the Caprivi Strip. Encouraged by South Africa's apparent failure to detect the initial incursion, larger insurgent groups made their own infiltration attempts in February and March 1966. The second unit, ''"Group 2"'', was led by Leonard Philemon Shuuya, also known by the ''nom de guerre'' "Castro" or "Leonard Nangolo". Group 2 apparently become lost in Angola before it was able to cross the border, and the guerrillas dispersed after an incident in which they killed two shopkeepers and a vagrant. Three were arrested by the Portuguese colonial authorities in Angola, working off tips received from local civilians. Another eight, including Shuuya, had been captured between March and May by the South African police, apparently in Kavangoland

Kavangoland was a bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Kavango people. It was set up in 1970 and self-government was granted in 1973. The Kavango L ...

. Shuuya later resurfaced at Kongwa, claiming to have escaped his captors after his arrest. He helped plan two further incursions: a third SWALA group entered Ovamboland that July, while a fourth was scheduled to follow in September.

On 18 July 1966, the ICJ ruled that it had no authority to decide on the South West African affair. Furthermore, the court found that while Ethiopia and Liberia had ''locus standi'' to institute proceedings on the matter, neither had enough vested legal interest in South West Africa to entitle them to a judgement of merits. This ruling was met with great indignation by SWAPO and the OAU. SWAPO officials immediately issued a statement from Dar es Salaam declaring that they now had "no alternative but to rise in arms" and "cross rivers of blood" in their march towards freedom. Upon receiving the news SWALA escalated its insurgency. Its third group, which had infiltrated Ovamboland in July, attacked white-owned farms, traditional Ovambo leaders perceived as South African agents, and a border post. The guerrillas set up camp at Omugulugwombashe

Omugulugwombashe (also: ''Ongulumbashe'', official: ''Omugulu gwOombashe''; Otjiherero: ''giraffe leg'') is a settlement in the Tsandi electoral constituency in the Omusati Region of northern Namibia. The settlement features a clinic and a primar ...

, one of five potential bases identified by SWALA's initial reconnaissance team as appropriate sites to train future recruits. Here, they drilled up to thirty local volunteers between September 1965 and August 1966. South African intelligence became aware of the camp by mid 1966 and identified its general location. On 26 August 1966, the first major clash of the conflict took place when South African paratroops and paramilitary police units executed Operation Blouwildebees to capture or kill the insurgents. SWALA had dug trenches around Omugulugwombashe for defensive purposes, but was taken by surprise and most of the insurgents quickly overpowered. SWALA suffered 2 dead, 1 wounded, and 8 captured; the South Africans suffered no casualties. This engagement is widely regarded in South Africa as the start of the Border War, and according to SWAPO, officially marked the beginning of its revolutionary armed struggle.

Operation Blouwildebees triggered accusations of treachery within SWALA's senior ranks. According to SADF accounts, an unidentified informant had accompanied the security forces during the attack. Sam Nujoma asserted that one of the eight guerrillas from the second group who were captured in Kavangoland was a South African mole. Suspicion immediately fell on Leonard "Castro" Shuuya. SWALA suffered a second major reversal on 18 May 1967, when Tobias Hainyeko, its commander, was killed by the South African police. Heinyeko and his men had been attempting to cross the Zambezi River

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

, as part of a general survey aimed at opening new lines of communication between the front lines in South West Africa and SWAPO's political leadership in Tanzania. They were intercepted by a South African patrol, and the ensuing firefight left Heinyeko dead and two policemen seriously wounded. Rumours again abounded that Shuuya was responsible, resulting in his dismissal and subsequent imprisonment.

In the weeks following the raid on Omugulugwombashe, South Africa had detained thirty-seven SWAPO politicians, namely Andimba Toivo ya Toivo

Herman Andimba Toivo ya Toivo (22 August 1924 – 9 June 2017) was a Namibian anti-apartheid activist, politician and political prisoner. Ya Toivo was active in the pre-independence movement, and is one of the co-founders of the South West Afri ...

, Johnny Otto, Nathaniel Maxuilili, and Jason Mutumbulua. Together with the captured SWALA guerrillas they were jailed in Pretoria and held there until July 1967, when all were charged retroactively under the Terrorism Act. The state prosecuted the accused as Marxist revolutionaries seeking to establish a Soviet-backed regime in South West Africa. In what became known as the "1967 Terrorist Trial", six of the accused were found guilty of committing violence in the act of insurrection, with the remainder being convicted for armed intimidation, or receiving military training for the purpose of insurrection. During the trial, the defendants unsuccessfully argued against allegations that they were privy to an external communist plot. All but three received sentences ranging from five years to life imprisonment on Robben Island

Robben Island ( af, Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrik ...

.

Expansion of the war effort and mine warfare

The defeat at Omugulugwombashe and subsequent loss of Tobias Hainyeko forced SWALA to reevaluate its tactics. Guerrillas began operating in larger groups to increase their chances of surviving encounters with the security forces, and refocused their efforts on infiltrating the civilian population. Disguised as peasants, SWALA cadres could acquaint themselves with the terrain and observe South African patrols without arousing suspicion. This was also a logistical advantage because they could only take what supplies they could carry while in the field; otherwise, the guerrillas remained dependent on sympathetic civilians for food, water, and other necessities. On 29 July 1967, the SADF received intelligence that a large number of SWALA forces were congregated at Sacatxai, a settlement almost a hundred and thirty kilometres north of the border inside Angola. South African T-6 Harvard warplanes bombed Sacatxai on 1 August. Most of their intended targets were able to escape, and in October 1968 two SWALA units crossed the border into Ovamboland. This incursion was no more productive than the others and by the end of the year 178 insurgents had been either killed or apprehended by the police. Throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, a limited military service system by lottery was implemented in South Africa to comply with the needs of national defence. Around mid 1967 the National Party government established universal conscription for all white South African men as the SADF expanded to meet the growing insurgent threat. From January 1968 onward there would be two yearly intakes of national servicemen undergoing nine months of military training. The air strike on Sacatxai also marked a fundamental shift in South African tactics, as the SADF had for the first time indicated a willingness to strike at SWALA on foreign soil. Although Angola was then anoverseas province

Overseas province ( pt, província ultramarina) was a designation used by Portugal for its overseas possessions, located outside Europe.

History

In the early the 19th century, Portuguese overseas territories were referred to as "overseas domini ...

of Portugal, Lisbon granted the SADF's request to mount punitive campaigns across the border. In May 1967 South Africa established a new facility at Rundu

Rundu is the capital and largest city of the Kavango-East Region in northern Namibia. It lies on the border with Angola on the banks of the Kavango River about above sea level. Rundu's population is growing rapidly. The 2001 census counted 36,9 ...

to coordinate joint air operations between the SADF and the Portuguese Armed Forces

The Portuguese Armed Forces ( pt, Forças Armadas) are the military of Portugal. They include the General Staff of the Armed Forces, the other unified bodies and the three service branches: Portuguese Navy, Portuguese Army and Portuguese Air ...

, and posted two permanent liaison officers at Menongue and Cuito Cuanavale.

As the war intensified, South Africa's case for annexation in the international community continued to decline, coinciding with an unparalleled wave of sympathy for SWAPO. Despite the ICJ's advisory opinions to the contrary, as well as the dismissal of the case presented by Ethiopia and Liberia, the UN declared that South Africa had failed in its obligations to ensure the moral and material well-being of the indigenous inhabitants of South West Africa, and had thus disavowed its own mandate. The UN thereby assumed that the mandate was terminated, which meant South Africa had no further right to administer the territory, and that henceforth South West Africa would come under the direct responsibility of the General Assembly. The post of United Nations Commissioner for South West Africa was created, as well as an ad hoc council, to recommend practical means for local administration. South Africa maintained it did not recognise the jurisdiction of the UN with regards to the mandate and refused visas to the commissioner or the council. On 12 June 1968, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution which proclaimed that, in accordance with the desires of its people, South West Africa be renamed ''Namibia''. United Nations Security Council Resolution 269

United Nations Security Council Resolution 269, adopted on August 12, 1969, condemned the government of South Africa for its refusal to comply with resolution 264, deciding that the continued occupation of South West Africa (now Namibia) was an a ...

, adopted in August 1969, declared South Africa's continued occupation of "Namibia" illegal. In recognition of the UN's decision, SWALA was renamed the People's Liberation Army of Namibia.

TM-46 mine

The TM-46 mine is a large, circular, metal-cased Soviet anti-tank mine. It uses either a pressure or tilt-rod fuze, which is screwed into the top. Anti-tank mines with this type of fuze were capable of inflicting much more damage to armored veh ...

s from the Soviet Union, which were designed for anti-tank purposes, and produced some homemade "box mines" with TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

for anti-personnel use. The mines were strategically placed along roads to hamper police convoys or throw them into disarray prior to an ambush; guerrillas also laid others along their infiltration routes on the long border with Angola. The proliferation of mines in South West Africa initially resulted in heavy police casualties and would become one of the most defining features of PLAN's war effort for the next two decades.

On 2 May 1971 a police van struck a mine, most likely a TM-46, in the Caprivi Strip. The resulting explosion blew a crater in the road about two metres in diameter and sent the vehicle airborne, killing two senior police officers and injuring nine others. This was the first mine-related incident recorded on South West African soil. In October 1971, another police vehicle detonated a mine outside Katima Mulilo

Katima Mulilo or simply Katima is the capital of the Zambezi Region in Namibia. It is located in the Caprivi Strip. It had 28,362 inhabitants in 2010, and comprises two electoral constituencies, Katima Mulilo Rural and Katima Mulilo Urban. I ...

, wounding four constables. The following day, a fifth constable was mortally injured when he stepped on a second mine laid directly alongside the first. This reflected a new PLAN tactic of laying anti-personnel mines parallel to their anti-tank mines to kill policemen or soldiers either engaging in preliminary mine detection or inspecting the scene of a previous blast. In 1972, South Africa acknowledged that two more policemen had died and another three had been injured as a result of mines.