Mykola Skrypnyk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mykola Oleksiiovych Skrypnyk ( uk, Микола Олексійович Скрипник; – 7 July 1933), also known as Nikolai Alekseyevich Skripnik (russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Скри́пник), was a Ukrainian

Skrypnyk worked for the

Skrypnyk worked for the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

revolutionary and Communist leader who was a proponent of the Ukrainian Republic's independence, and later led the cultural Ukrainization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

effort in Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

. When the policy was reversed and he was removed from his position, he committed suicide rather than be forced to recant his policies in a show trial. He also was the Head of the Ukrainian People's Commissariat, equivalent to the modern-day position of Prime Minister of Ukraine

The prime minister of Ukraine ( uk, Прем'єр-міністр України, ) is the head of government of Ukraine. The prime minister presides over the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, which is the highest body of the executive branch of th ...

.

Early life and career

Skrypnyk was born in the villageYasynuvata

Yasynuvata ( uk, Ясинува́та, ; russian: Ясиноватая — Yasinovataya) is a city in Donetsk Oblast (province) of south-eastern Ukraine. Administratively, it is incorporated as a city of oblast significance. It also serves as th ...

of Bakhmut uyezd, Yekaterinoslav Governorate

The Yekaterinoslav Governorate (russian: Екатеринославская губерния, Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya; uk, Катеринославська губернія, translit=Katerynoslavska huberniia) or Government of Yekaterinos ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in the family of a railway telegraph operator, assistant to the chief of the railway station; his mother worked as a midwife in the Zemstvo

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexande ...

hospital.

At first he studied at the Barvinkove

Barvinkove () or Barvenkovo () is a city in Izium Raion of Kharkiv Oblast of Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Barvinkove urban hromada, one of the communities of Ukraine. locally referred to as Barvinkove Population:

History

Barvinkove ...

elementary school, then realschule

''Realschule'' () is a type of secondary school in Germany, Switzerland and Liechtenstein. It has also existed in Croatia (''realna gimnazija''), the Austrian Empire, the German Empire, Denmark and Norway (''realskole''), Sweden (''realskola''), ...

s of the cities Izium

Izium or Izyum ( uk, Ізюм, ; russian: Изюм) is a city on the Donets River in Kharkiv Oblast (province) of eastern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Izium Raion (district). Izium hosts the administration of Izium urban ...

, from which he was expelled for revolutionary activities, and Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German stru ...

, which he graduated from in 1890. During his studies he became acquainted with Ukrainian history and literature, in particular with the works of Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

and Panteleimon Kulish

Panteleimon Oleksandrovych Kulish (also spelled ''Panteleymon'' or ''Pantelejmon Kuliš'', uk, Пантелеймон Олександрович Куліш, August 7, 1819 – February 14, 1897) was a Ukrainian writer, critic, poet, folkloris ...

.

Originally a member of the Saint Petersburg Hromada society, Skrypnyk became a member of "Workers' Banner", part of the Marxist social democratic movement, in 1897. Skrypnyk joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

("RSDLP") in 1898.

While studying at Saint Petersburg State Institute of Technology in 1901, he was arrested on political charges, prompting him to become a full-time revolutionary. Skrypnyk was eventually expelled from the Institute.

He was arrested between fifteen and seventeen times, exiled seven times, and at one point was sentenced to death. He escaped from his first exile in the Yakut region, then worked as a social-democratic organizer and propagandist in Tsaritsyn

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stalingrád, label=none; ) ...

(1902), Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901, ...

(1902-1903), Samara

Samara ( rus, Сама́ра, p=sɐˈmarə), known from 1935 to 1991 as Kuybyshev (; ), is the largest city and administrative centre of Samara Oblast. The city is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Samara rivers, with a population ...

and Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

(1903), Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

(1903-1904) and Katerynoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

(1904), from which he was exiled for five years to the Kem district of the Arkhangelsk Governate. Skrypnyk escaped on the way to his exile and moved to Odessa.

In 1905, he was a party organizer of the Nevsky District

Nevsky District (russian: Не́вский райо́н) is a district of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia. As of the 2010 Census, its population was 466,013; up from 438,061 recorded in the 2002 Census.

Geography

The distr ...

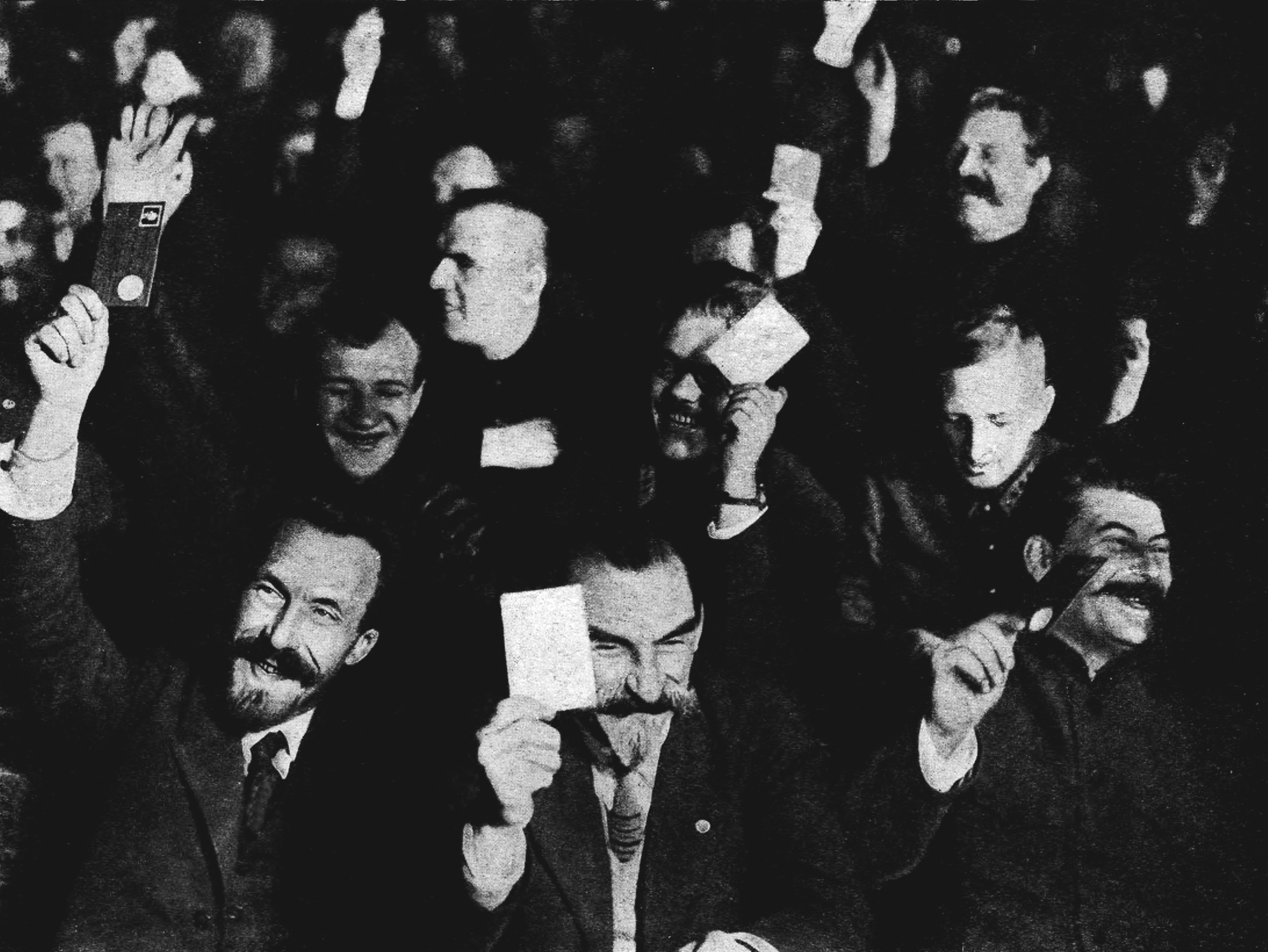

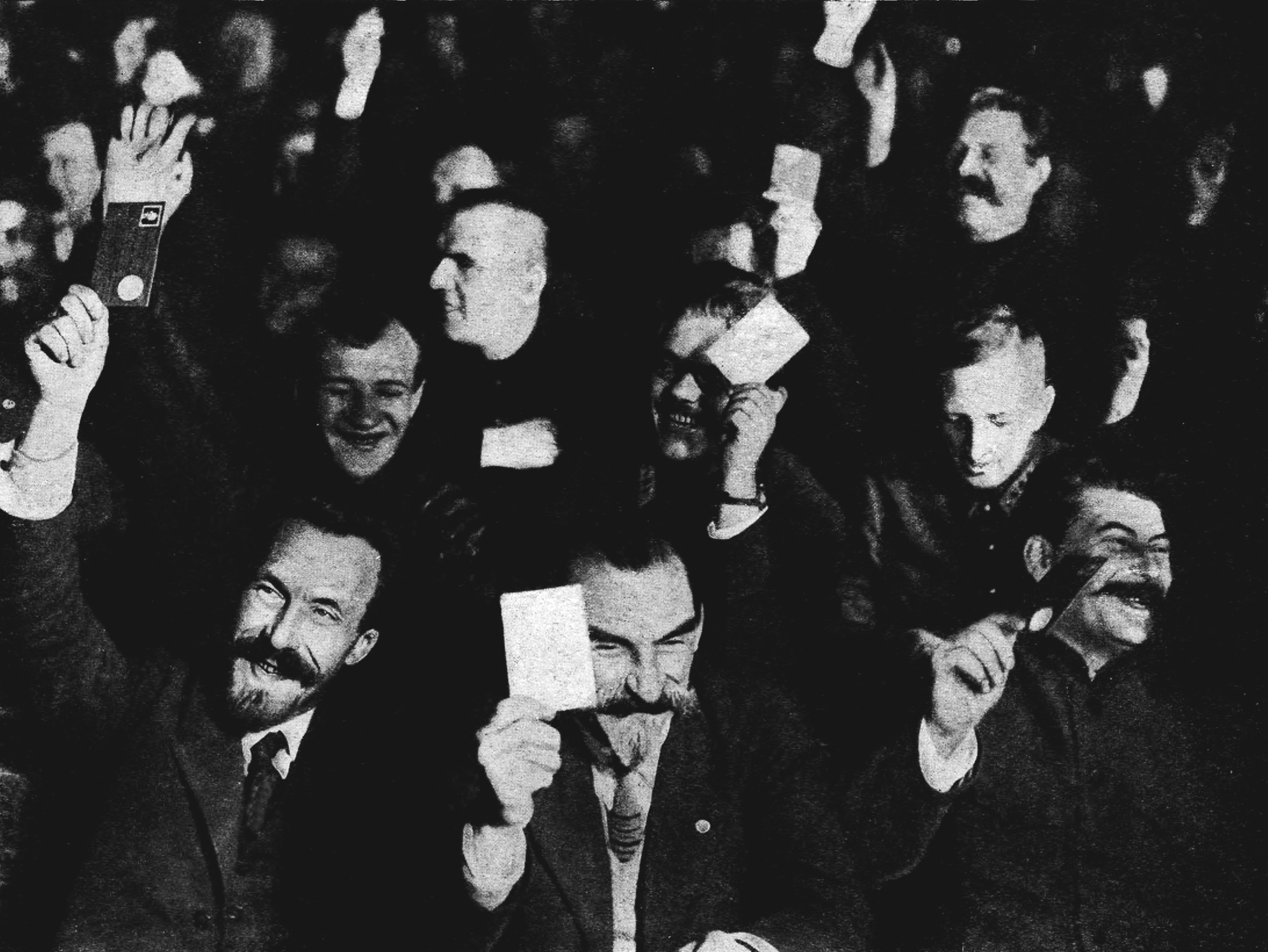

of St. Petersburg, then the secretary of the Petersburg Committee of the RSDLP. He was elected as a delegate to the 3rd London Congress of the RSDLP in that year.

In October 1905, he became a member of the Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the ...

Committee of the RSDLP. At the end of December 1905, he moved to Yaroslavl

Yaroslavl ( rus, Ярослáвль, p=jɪrɐˈsɫavlʲ) is a city and the administrative center of Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, located northeast of Moscow. The historic part of the city is a World Heritage Site, and is located at the confluenc ...

, where he was arrested and exiled for five years to the Turukhansky region. During this exile, he fled to the city of Krasnoyarsk

Krasnoyarsk ( ; rus, Красноя́рск, a=Ru-Красноярск2.ogg, p=krəsnɐˈjarsk) (in semantic translation - Red Ravine City) is the largest city and administrative center of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. It is situated along the Y ...

, where he conducted the election campaign of the RSDLP to the Second State Duma of the Russian Empire. He was arrested and sent to Turukhansk

Turukhansk (russian: Туруха́нск) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Turukhansky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, located north of Krasnoyarsk, at the confluence of the Yenisey and Nizhnyaya Tu ...

, from which he soon escaped, having covered 1,200 versts, or an equivalent number of kilometers, by boat and on foot.

In the summer of 1908, he went to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

for a month and a half. After his return, he worked as a party organizer and a member of the Central Bureau of Trade Unions in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. He was arrested and spent three months in a Moscow prison. After his release, he worked as a district organizer, secretary of the Moscow Committee of the RSDLP(b), and was dispatched on a campaign trip to the Urals.

At the end of 1908, he was arrested in St. Petersburg and exiled for five years to the Vilyuysky District

Vilyuysky District (russian: Вилю́йский улу́с; sah, Бүлүү улууһа, ''Bülüü uluuha'', ) is an administrativeConstitution of the Sakha Republic and municipalLaw #172-Z #351-III district (raion, or ''ulus''), one of the th ...

of the Yakut region. He returned from exile at the end of 1913.

In 1913 Skrypnyk was an editor of the Bolsheviks' legal magazine ''Issues of Insurance'' and in 1914 was a member of the editorial board of the ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' newspaper, while also working for Iskra

''Iskra'' ( rus, Искра, , ''the Spark'') was a political newspaper of Russian socialist emigrants established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

History

Due to political repression under Tsar Nicho ...

. He used the party pseudonyms Glasson, Peterburzhets, Valerian, H. Yermolaev, Shchur, and Schensky.

In July 1914, he was arrested again, sentenced to administrative exile in the city of Morshansk, Tambov Governorate

Tambov Governorate was an administrative unit of the Russian Empire, Russian Republic, and later the Russian SFSR, centred around the city of Tambov. The governorate was located between 51°14' and 55°6' north and between 38°9' and 43°38' east ...

, where he worked as an accountant in a Morshanska bank.

Russian Revolution

After theFebruary Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

, Skrypnyk was amnestied by the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

and moved to Petrograd, as St. Petersburg was now known, where he was elected as a secretary of the Central Council of Factories Committees. During the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, Skrypnyk was a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (russian: Военно-революционный комитет, ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – Marc ...

of the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

.

In December 1917, Skrypnyk was elected in absentia to the first Bolshevik government of Ukraine, the so-called People's Secretariat, in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

(''Respublika Rad Ukrayiny'') as the People's Secretary of Labor. From February to March 1918, he was the People's Secretary of Trade and Industry of the Ukrainian People's Republic. On March 3, 1918 he was elected president of the Secretariat, replacing Yevgenia Bosch

Yevgenia Bogdanovna; russian: Го́тлибовна) Bosch; russian: Евге́ния Богда́новна Бош; german: Jewgenija Bogdanowna Bosch (née Meisch ; – 5 January 1925) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary, politician, ...

, daughter of a German immigrant, who had resigned in protest against the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

. From March 8 to April 18, 1918, he also served as the People's Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

The Soviet Ukrainian government, under the onslaught of German troops, ended up in Katerynoslav, and later in Taganrog

Taganrog ( rus, Таганрог, p=təɡɐnˈrok) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of the Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don River. Population:

History of Taganrog

Th ...

, where it ceased to exist. On March 17-19, 1918, the II All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets was held in Katerynoslav, which proclaimed the independence of Soviet Ukraine. On April 18, 1918, Skrypnyk was elected a member of the All-Ukrainian Bureau to lead the insurgent struggle against the German occupiers. At the so-called Taganrog meeting (April 19-20, 1918), Skrypnyk was elected secretary of the Organizational Bureau for the 1st Congress of the Central Committee of the CP(b)U at its first congress held in Moscow (July 5-12, 1918), where he was the main speaker. But after the congress, he was removed from the leadership of the CP(b)U and left in Moscow.

Skrypnyk was a leader in the so-called Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

faction of the Ukrainian Bolsheviks, the independentists, sensitive to the issue of nationality, and promoting a separate Ukrainian Bolshevik party, while members of the predominantly Russian Katerynoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

faction preferred joining the All-Russian Communist Party in Moscow, according to Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's internationalist doctrine. The Kyiv faction won a compromise at a conference in Taganrog

Taganrog ( rus, Таганрог, p=təɡɐnˈrok) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of the Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don River. Population:

History of Taganrog

Th ...

, Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

in April 1918, when the Bolshevik government was dissolved and the delegates voted to form an independent Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine ( uk, Комуністична Партія України ''Komunistychna Partiya Ukrayiny'', КПУ, ''KPU''; russian: Коммунистическая партия Украины) was the founding and ruling ...

, CP(b)U. But in July a Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

congress of Ukrainian Bolsheviks rescinded the resolution and the Ukrainian party was declared a part of the Russian Communist Party. Skrypnyk worked for the

Skrypnyk worked for the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

secret police during the winter of 1918–19, then was the head of the special department of the Cheka of the South-Eastern and Caucasian Fronts. He returned to Ukraine, where he was a special commissioner of the Defense Council for combating the insurgent movement and led the suppression of the rebellion of Ataman Zelenyi. He later served as People's Commissar of Worker-Peasant Inspection (1920–21) and Internal Affairs (1921–22).

During debates leading up to the formation of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in late 1922, Skrypnyk was a proponent of independent national republics and denounced the proposal of the new General Secretary, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, to absorb them into a single Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

state as thinly-disguised Russian chauvinism. Lenin temporarily swayed the decision in favour of the republics, but after his death, the Soviet Union's constitution was finalized in January 1924 with very little political autonomy for the republics. Having lost this battle, Skrypnyk and other autonomists would turn their attention towards culture.

Skrypnyk was Commissar of Justice between 1922 and 1927 and the Commissar of Education of the USSR from March 7, 1927 to February 28, 1933. He was a member of the executive committee of the Communist International from September 1, 1928 to July 7, 1933.

Ukrainization

Skrypnyk was appointed head of the Ukrainian Commissariat of Education in 1927. He convinced the Central Committee of the CP(b)U to introduce the policy ofUkrainization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

, encouraging Ukrainian culture and literature. He worked for this cause with almost obsessive zeal and, despite a lack of teachers and textbooks and in the face of bureaucratic resistance, achieved tremendous results during 1927–29. The Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state lan ...

was institutionalized in the schools and society and literacy rates reached a very high level. As Soviet industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and collectivization drove the population from the countryside to urban centres, Ukrainian started to change from a peasants' tongue and the romantic obsession of a small intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

into a primary language of a modernizing society.

Skrypnyk convened an international Orthographic Conference in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

in 1927, hosting delegates from Soviet and western Ukraine (former territories of Austro-Hungarian Galicia, then part of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

). The conference settled on a compromise between Soviet and Galician orthographies, and published the first standardized Ukrainian alphabet

The Ukrainian alphabet ( uk, абе́тка, áзбука алфа́ві́т, abetka, azbuka alfavit) is the set of letters used to write Ukrainian, which is the official language of Ukraine. It is one of several national variations of the ...

accepted in all of Ukraine. The Ukrainian orthography of 1928 The Ukrainian orthography of 1928 ( uk, Український правопис 1928 року, translit=Ukrainskyi pravopys 1928 roku), also Orthography of Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рківський право́пис, translit=Kharkivskyi pravopys) is ...

, also known as Kharkiv orthography or ''Skrypnykivka'', was officially adopted in 1928.

Although he was a supporter of an autonomous Ukrainian republic and the driving force behind Ukrainization, Skrypnyk's motivation was what he saw as the best way to achieve communism in Ukraine, and he remained politically opposed to Ukrainian nationalism. He gave public testimony against "nationalist deviations" such as writer Mykola Khvylovy

Mykola Khvylovy ( ; – May 13, 1933) (who also used the pseudonyms "Yuliya Umanets", "Stefan Karol", and "Dyadko Mykola") was a Ukrainian novelist, poet, publicist, and political activist, one of the founders of post-revolutionary Ukrain ...

's literary independence movement, political anticentralism represented by former Borotbist Oleksandr Shumsky, and Mykhailo Volobuev's criticism of Soviet economic policies which made Ukraine dependent on Russia.

From February to July 1933, Skrypnyk headed the Ukrainian State Planning Commission, became a member of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

of the CP(b)U and served on the Executive Committee organizing the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, as well as leading the CP(b)U's delegation to the Comintern.

Great Purge

In January 1933, Stalin sent Pavel Postyshev to Ukraine, with free rein to centralize the power of Moscow. Postyshev, with the help of thousands of officials brought from Russia, oversaw the violent reversal of Ukrainization, enforced collectivization of agriculture, and conducted apurge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

of the CP(b)U, anticipating the wider Soviet Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

which was to follow in 1937.

Skrypnyk was removed as head of Education. In June, he and his "nefarious" policies were publicly discredited and his followers condemned as "wrecking, counterrevolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

nationalist elements". Rather than recant, on 7 July he shot himself at his desk at his apartment in Derzhprom

The Derzhprom ( uk, Держпром) or Gosprom (russian: Госпром) building is an office building located on Freedom Square in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Built in the Constructivist style, it was the first modern skyscraper building in ...

at Dzerzhynsky Square (Dzerzhynsky Municipal Raion of Kharkiv city).

During the remainder of the 1930s, Skrypnyk's "forced Ukrainization" was reversed.

He was rehabilitated in 1962.

Personal life

His first wife Maria Mykolaivna Skrypnyk (maiden name Mezhova; 1883 - 1968) was a Bolshevik from pre-revolutionary times, a member of the Krasnoyarsk organization of the RSDLP, where they met. At the end of 1917 - the beginning of 1918, she worked as the secretary of the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR Vladimir Lenin, in 1919-1920; she later served as a member of the collegium of the People's Commissariat of Land Affairs and the People's Commissariat of Social Security of the USSR, then worked as a teacher and authored her memoirs about Lenin. They separated in the 1920s, at which point she moved to Moscow, while he stayed in Kharkiv. His second wife was Raisa Leonidivna Khavina (born in 1904, Gomel, in some sources her last name is given as Petrova), much younger than her husband. After Skrypnyk's death, she was arrested, but soon released. She moved to Moscow, where she worked as an engineer of the prescription commission of "Aniltrest". In 1938, she was arrested again and executed on August 20, 1938, and her son Mykola was sent to an orphanage; he died at the front during the war.See also

*People's Secretariat

The People's Secretariat of Ukraine was the executive body of the Provisional Central Executive Committee of Soviets in Ukraine. It was formed in Kharkiv on December 30, 1917 as a form of the Soviet concept of dual power by the Russian and other ...

, the first government of the Soviet Ukraine

Notes

Further reading

* Includes a concise biography of Skrypnyk in annotation no. 25. * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Skrypnyk, Mykola 1872 births 1933 deaths People from Yasynuvata People from Yekaterinoslav Governorate Ukrainian people in the Russian Empire Old Bolsheviks Saint Petersburg State Institute of Technology alumni Hromada (society) members Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Directors of the State Planning Committee of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) politicians Politicians of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Cheka Russian revolutionaries Ukrainian revolutionaries Deaths by firearm in Ukraine General Prosecutors of Ukraine Soviet justice ministers of Ukraine Ukrainian diplomats Soviet foreign ministers of Ukraine Soviet interior ministers of Ukraine Chairpersons of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine Institute of History of the Party (Ukraine) directors Soviet labor ministers of Ukraine Education ministers of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Vice Prime Ministers of Ukraine Executive Committee of the Communist International Members of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Ukrainian politicians who committed suicide Soviet politicians who committed suicide 1933 suicides Ukrainian Marxists