Mykhaylo Maksymovych on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mykhailo Oleksandrovych Maksymovych ( uk, Михайло Олександрович Максимович; 3 September 1804 – 10 November 1873) was a famous professor in

Mykhailo Oleksandrovych Maksymovych ( uk, Михайло Олександрович Максимович; 3 September 1804 – 10 November 1873) was a famous professor in

Maksymovych was born into an old

Maksymovych was born into an old

Maksymovych was a pioneer of his time and, in many ways, one of the last of the "universal men" who were able to contribute original works to both the sciences and the humanities. His works in biology and the physical sciences reflected a concern for the common man - love for his fellow human being, Schelling's philosophy, at work - and his works in literature, folklore, and history, often phrased in terms of friendly public "letters" to his scholarly opponents, pointed to new directions in telling the story of the common people. In doing this, however, Maksymovych "awakened" new national sentiments among his fellows, especially the younger generation. He greatly influenced many of his younger contemporaries including the poet

Maksymovych was a pioneer of his time and, in many ways, one of the last of the "universal men" who were able to contribute original works to both the sciences and the humanities. His works in biology and the physical sciences reflected a concern for the common man - love for his fellow human being, Schelling's philosophy, at work - and his works in literature, folklore, and history, often phrased in terms of friendly public "letters" to his scholarly opponents, pointed to new directions in telling the story of the common people. In doing this, however, Maksymovych "awakened" new national sentiments among his fellows, especially the younger generation. He greatly influenced many of his younger contemporaries including the poet

Mykhailo Maksymovych

on

Максимович Михаил Александрович

на сайте проекта «Хронос» {{DEFAULTSORT:Maksymovych, Mykhailo 1804 births 1873 deaths People from Cherkasy Oblast People from Poltava Governorate Ukrainian people in the Russian Empire 19th-century botanists from the Russian Empire Historians from the Russian Empire Writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century Ukrainian historians Ukrainian folklorists Ukrainianists Moscow State University alumni Moscow State University faculty Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Rectors of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv faculty

Mykhailo Oleksandrovych Maksymovych ( uk, Михайло Олександрович Максимович; 3 September 1804 – 10 November 1873) was a famous professor in

Mykhailo Oleksandrovych Maksymovych ( uk, Михайло Олександрович Максимович; 3 September 1804 – 10 November 1873) was a famous professor in plant biology

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Gree ...

, Ukrainian historian and writer in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

of a Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

background.

He contributed to the life sciences, especially botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

, and to linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Ling ...

, folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

, ethnography

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject ...

, history, literary studies, and archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsc ...

.

In 1871 he was elected as a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

, Russian language and literature department. Maksymovych also was a member of the Nestor the Chronicler Historical Association that existed in Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

in 1872-1931.

Life

Maksymovych was born into an old

Maksymovych was born into an old Zaporozhian Cossack

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

family which owned a small estate on Mykhailova Hora near Prokhorivka, Zolotonosha county in Poltava Governorate

The Poltava Governorate (russian: Полтавская губерния, Poltavskaya guberniya; ua, Полтавська Губернія, translit=Poltavska huberniia) or Poltavshchyna was a gubernia (also called a province or government) in t ...

(now in Cherkasy Oblast

Cherkasy Oblast ( uk, Черка́ська о́бласть, Cherkaska oblast, ), also referred to as Cherkashchyna ( uk, Черка́щина, ) is an oblast (province) of central Ukraine located along the Dnieper River. The administrative center ...

) in Left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine ( uk, Лівобережна Україна, translit=Livoberezhna Ukrayina; russian: Левобережная Украина, translit=Levoberezhnaya Ukraina; pl, Lewobrzeżna Ukraina) is a historic name of the part of Ukrain ...

. After receiving his high school education at Novhorod-Siverskyi

Novhorod-Siverskyi ( uk, Новгород-Сіверський ) is a historic city in Chernihiv Oblast (province) of Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Novhorod-Siverskyi Raion, although until 18 July 2020 it was incorporated as a city ...

Gymnasium, he studied natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

and philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

at philosophy faculty of Moscow University

M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU; russian: Московский государственный университет имени М. В. Ломоносова) is a public research university in Moscow, Russia and the most prestigious ...

and later the medical faculty, graduating with his first degree in 1823, his second in 1827; thereafter, he remained at the university in Moscow for further academic work in botany. In 1833 he received his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

and was appointed as a professor for the chair of botany in the Moscow University.

He taught biology and was director of the botanical garden at the university. During this period, he published extensively on botany and also on folklore and literature, and got to know many of the leading lights of Russian intellectual life including the Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

and Russian writer, Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

, and shared his growing interest in Cossack history with them.

In 1834, he was appointed professor of Russian literature at the newly created Saint Vladimir University

Kyiv University or Shevchenko University or officially the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv ( uk, Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка), colloquially known as KNU ...

in Kyiv and also became the university's first rector, a post that he held until 1835. (This university had been established by the Russian government to reduce Polish influence in Ukraine and Maksymovych was, in part, an instrument of this policy). Maksymovych elaborated wide-ranging plans for the expansion of the university which eventually included attracting eminent Ukrainians and Russians like, Nikolay Kostomarov, and Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

to teach there.

In 1847, he was deeply affected by the arrest, imprisonment, and exile of the members of the Pan-Slavic Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

The Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius ( uk, Кирило-Мефодіївське братство, russian: Кирилло-Мефодиевское братство) was a short-lived secret political society that existed in Kiev (now Kyi ...

, many of whom, like the poet Taras Shevchenko, were his friends or students. Thereafter, he buried himself in scholarship, publishing extensively.

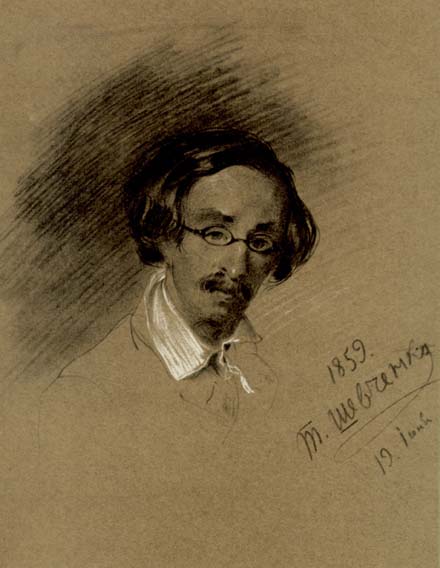

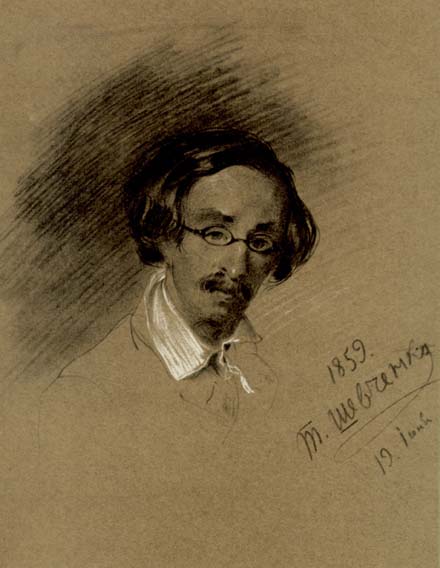

In 1853, he married, and in 1857, in hope of relieving his severe financial situation, went to Moscow to find work. In 1858, Taras Shevchenko returning from exile, visited him in Moscow, and when Maksymovych returned to Mykhailova Hora, visited him there as well. At this time, Shevchenko painted portraits of both Maksymovych and his wife, Maria.

During his final years, Maksymovych devoted himself more and more to history and engaged in extensive debates with the Russian historians Mikhail Pogodin and Nikolay Kostomarov.

The physical sciences and philosophy

In the 1820s and 1830s, Maksymovych published several textbooks on biology and botany. His first scholarly book on botany was published in 1823 under the title ''On the System of the Flowering Kingdom''. He also published popular works on botany for the layman. This "populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

" approach to science, he carried over into his writings on folklore, literature, and history.

In 1833 in Moscow, he published ''The Book of Naum About God's Great World'', which was a popularly written exposition of geology, the solar system, and the universe, in religious garb for the common folk. This book proved to be a best-seller and went through eleven editions, providing Maksymovych with some royalties for many long years.

Also in 1833, Maksymovych published "A Letter on Philosophy" which reflected his admiration for Schelling's "Nature-Philosophy." In this letter, he declared that true philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

was based on love and that all branches of organized, systematic knowledge, which strove to recognize the internal meaning and unity of things, but most especially history, were philosophy. With his emphasis upon history, Maksymovych approached the views of Baader

Baader is a surname of German origin.

People with the surname Baader

* Andreas Baader (1943–1977), militant of the Red Army Faction (Rote Armee Fraktion), also known as the ''Baader Meinhoff Gang''

* Caspar Baader (born 1953), Swiss politicia ...

and Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

as well as Schelling.

Folklore

In 1827, Maksymovych published ''Little Russian Folksongs'' which was one of the first collections offolk song

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has ...

s published in eastern Europe. It contained 127 songs, including historical songs, songs about every-day life, and ritual songs. The collection marked a new turning to the common people, the folk, which was the hallmark of the new romantic era which was then beginning. Everywhere that it was read, it aroused the interest of the literate classes in the life of the common folk. In 1834 and in 1849, Maksymovych published two further collections.

In his collections of folksongs, Maksymovych used a new orthography for the Ukrainian language which was based on etymology. Although this ''Maksymovychivka'' looked quite similar to Russian, it was a first step towards an independent orthography, based on phonetics which was eventually proposed by Maksymovych's younger contemporary, Panteleimon Kulish

Panteleimon Oleksandrovych Kulish (also spelled ''Panteleymon'' or ''Pantelejmon Kuliš'', uk, Пантелеймон Олександрович Куліш, August 7, 1819 – February 14, 1897) was a Ukrainian writer, critic, poet, folkloris ...

. The latter forms the basis of the modern written Ukrainian language.

In general, Maksymovych claimed to see some basic psychological differences, reflecting differences in national character, between Ukrainian and Russian folk songs; he thought the former more spontaneous and lively, the latter more submissive. Such opinions were shared by many of his contemporaries such as his younger contemporary, the historian Nikolay Kostomarov and others.

In 1856, Maksymovych published the first part of his "Days and Months of the Ukrainian Villager" which summed up many years of observation of the Ukrainian peasantry. In it, he laid out the folk customs of the Ukrainian village according to the calendar year. (The full work was only published in Soviet times.)

Language and literature

In 1839, Maksymovych published his ''History of Old Russian Literature'' which dealt with the so-called Kyivan period of Russian literature. Maksymovych saw a definite continuity between the language and literature ofRuthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

(Kyivan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

) and that of Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

period. Indeed, he seems to have thought that the Old Ruthenian language stood in relation to modern Russian in a way similar to that of Old Czech to modern Polish or modern Slovak; that is, that one influenced but was not the same as the other. Later on, he also translated the epic ''Tale of Igor's Campaign'' into both modern Russian and modern Ukrainian verse. Maksymovych's literary works included poetry and almanacs with much material devoted to Russia.

History

From the 1850s to the 1870s, Maksymovych worked extensively in history, especially Russian and Ukrainian history. He was critical of the Normanist theory which tracedKyivan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

to Scandinavian origins, preferring to stress its Slavic roots. But he opposed the Russian historian, Mikhail Pogodin, who believed that Kyivan Rus' originally had been populated by Great Russians from the north. Maksymovych argued that the Kyivan lands were never completely de-populated, even after the Mongol invasions, and that they had always been inhabited by Ruthenians and their direct ancestors. As well, he was the first to claim the "Lithuanian period" for Russian history. Maksymovych also worked on the history of the city of Kyiv, of Cossack Hetmanate, of the uprising of Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

, the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising,; in Ukraine known as Khmelʹnychchyna or uk, повстання Богдана Хмельницького; lt, Chmelnickio sukilimas; Belarusian: Паўстанне Багдана Хмяльніцкага; russian: � ...

against Poland, and other subjects. In general, he sympathized with these various Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

rebels, so much so, in fact, that his first work on the Haidamaks was banned by the Russian censor. Many of his most important works were critical studies and corrections of the publications of other historians, like Mikhail Pogodin and Nikolay Kostomarov.

Slavistics

With regard to Slavic studies, Maksimovich remarked upon the various theses of the Czech philologist, Josef Dobrovský and the Slovak scholar,Pavel Jozef Šafárik

Pavel Jozef Šafárik ( sk, Pavol Jozef Šafárik; 13 May 1795 – 26 June 1861) was an ethnic Slovak philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavists.

Family ...

. Like them, he divided the Slavic family into two major groups, a western group and an eastern group. But then he sub-divided the western group into two further parts: a north-western group and a south-western group. (Dobrovsky had lumped the Russians together with the South Slavs.) Maksymovych particularly objected to Dobrovsky's contention that the major eastern or Russian group was unified, without major divisions or dialects. This eastern group, Maksymovych divided into two independent languages, South Russian and North Russian. The South Russian language, he divided into two major dialects, Ruthenian and Red Ruthenian/Galician. The North Russian language, he divided into four major dialects of which he thought the Muscovite the most developed, but also the youngest. In addition to this, he also seems to have considered Belarusian to be an independent language, intermediate between North and South Russian, but much closer to the former. Writing at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Croatian scholar Vatroslav Jagić

Vatroslav Jagić (; July 6, 1838 – August 5, 1923) was a Croatian scholar of Slavic studies in the second half of the 19th century.

Life

Jagić was born in Varaždin (then known by its German name of ''Warasdin''), where he attended the el ...

thought Maksymovych's scheme to have been a solid contribution to Slavic philology.

Maksymovych also argued in favour of the independent origin of the spoken Old Rus languages, thinking them separate from the book language of the time which was based on Church Slavonic. Maksymovych also made some critical remarks on Pavel Jozef Šafárik

Pavel Jozef Šafárik ( sk, Pavol Jozef Šafárik; 13 May 1795 – 26 June 1861) was an ethnic Slovak philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavists.

Family ...

's map of the Slavic world, wrote on the Lusatian Sorbs

Sorbs ( hsb, Serbja, dsb, Serby, german: Sorben; also known as Lusatians, Lusatian Serbs and Wends) are a indigenous West Slavic ethnic group predominantly inhabiting the parts of Lusatia located in the German states of Saxony and Brandenb ...

, and on Polish proverb

A proverb (from la, proverbium) is a simple and insightful, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and use formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbia ...

s. Maksimovich, as well, wrote a brief autobiography which was first published in 1904. His correspondence was large and significant.

Legacy

Maksymovych was a pioneer of his time and, in many ways, one of the last of the "universal men" who were able to contribute original works to both the sciences and the humanities. His works in biology and the physical sciences reflected a concern for the common man - love for his fellow human being, Schelling's philosophy, at work - and his works in literature, folklore, and history, often phrased in terms of friendly public "letters" to his scholarly opponents, pointed to new directions in telling the story of the common people. In doing this, however, Maksymovych "awakened" new national sentiments among his fellows, especially the younger generation. He greatly influenced many of his younger contemporaries including the poet

Maksymovych was a pioneer of his time and, in many ways, one of the last of the "universal men" who were able to contribute original works to both the sciences and the humanities. His works in biology and the physical sciences reflected a concern for the common man - love for his fellow human being, Schelling's philosophy, at work - and his works in literature, folklore, and history, often phrased in terms of friendly public "letters" to his scholarly opponents, pointed to new directions in telling the story of the common people. In doing this, however, Maksymovych "awakened" new national sentiments among his fellows, especially the younger generation. He greatly influenced many of his younger contemporaries including the poet Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

, the historian Nikolay Kostomarov, the writer Panteleimon Kulish

Panteleimon Oleksandrovych Kulish (also spelled ''Panteleymon'' or ''Pantelejmon Kuliš'', uk, Пантелеймон Олександрович Куліш, August 7, 1819 – February 14, 1897) was a Ukrainian writer, critic, poet, folkloris ...

, and many others.

The library of Kyiv University is named in his honour.

Further reading

*Dmytro Doroshenko

Dmytro Doroshenko ( uk, Дмитро Іванович Дорошенко, ''Dmytro Ivanovych Doroshenko'', russian: Дми́трий Ива́нович Дороше́нко; 8 April 1882 – 19 March 1951) was a prominent Ukrainian political figu ...

, "A Survey of Ukrainian Historiography", ''Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the US'', Vol. V-VI (1957), section on Maksymovych, pp. 119–23.

* George S. N. Luckyj

George Stephen Nestor Luckyj (born Юрій Луцький, transcribed: Yuriy Lutskyy; Yanchyn, now Ivanivka, Lviv Oblast, 1919 — Toronto, November 22, 2001) was a scholar of Ukrainian literature, who greatly contributed to the awareness of ...

, ''Between Gogol and Ševčenko: Polarity in the Literary Ukraine, 1798-1847'' (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1971), ''passim''. Good on his relations with Gogol, Shevchenko, Kulish, and Kostomarov.

* Mykhailo Maksymovych, ''Kyiv iavilsia gradom velikim'' (Kyiv: Lybid, 1994). Contains a collection of Maksymovych's writings on Ukraine, his brief autobiography, and a biographical introduction by V. Zamlynsky. Texts in Ukrainian and Russian.

* Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky ( uk, Михайло Сергійович Грушевський, Chełm, – Kislovodsk, 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figure ...

, "'Malorossiiskie pesni' Maksymovycha i stolittia ukrainskoi naukovoi pratsi", The 'Little Russian Songs' of Maksymovych and the Centennial of Ukrainian Scholarly Work"''Ukraina'', no.6 (1927), 1-13; reprinted in ''Ukrainskyi istoryk'', XXI, 1-4 (1984), 132-147. Incisive and important essay by the most famous of modern Ukrainian historians.

* M. B. Tomenko, "'Shchyryi Malorosiianyn': Vydatnyi vchenyi Mykhailo Maksymovych", A Sincere Little Russian': The Outstanding Scholar Mykhailo Maksymovychin ''Ukrainska ideia. Pershi rechnyky'' (Kyiv: Znannia, 1994), pp. 80–96, An excellent short sketch.

* M. Zh., "Movoznavchi pohliady M. O. Maksymovycha", ''Movoznavstvo'', no. 5 (1979), 46-50. Makes the claim that Maksymovych was one of the first to recognise the threefold division of the Slavic languages.

* Article on Maksymovych, in the ''Dovidnyk z istorii Ukrainy'', ed. I. Pidkova and R. Shust (Kyiv: Heneza, 2002), pp. 443–4. Also available on-line.

References

External links

Mykhailo Maksymovych

on

Encyclopedia of Ukraine

The ''Encyclopedia of Ukraine'' ( uk, Енциклопедія українознавства, translit=Entsyklopediia ukrainoznavstva), published from 1984 to 2001, is a fundamental work of Ukrainian Studies.

Development

The work was creat ...

website

Максимович Михаил Александрович

на сайте проекта «Хронос» {{DEFAULTSORT:Maksymovych, Mykhailo 1804 births 1873 deaths People from Cherkasy Oblast People from Poltava Governorate Ukrainian people in the Russian Empire 19th-century botanists from the Russian Empire Historians from the Russian Empire Writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century Ukrainian historians Ukrainian folklorists Ukrainianists Moscow State University alumni Moscow State University faculty Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Rectors of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv faculty