Music technology (mechanical) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mechanical music technology is the use of any device, mechanism, machine or tool by a musician or composer to make or perform music; to

Mechanical music technology is the use of any device, mechanism, machine or tool by a musician or composer to make or perform music; to

Findings from

Findings from

In

In

According to the

According to the  In addition there was the

In addition there was the

In

In

The Romans may have borrowed the Greek method of 'enchiriadic notation' to record their music, if they used any notation at all. Four letters (in English notation 'A', 'G', 'F' and 'C') indicated a series of four succeeding tones. Rhythm signs, written above the letters, indicated the duration of each note.

The Romans may have borrowed the Greek method of 'enchiriadic notation' to record their music, if they used any notation at all. Four letters (in English notation 'A', 'G', 'F' and 'C') indicated a series of four succeeding tones. Rhythm signs, written above the letters, indicated the duration of each note.

During the

During the  Instruments used to perform medieval music include the early flute, which was made of wood and which did not have any metal keys or pads. Flutes of this era could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument; the wooden

Instruments used to perform medieval music include the early flute, which was made of wood and which did not have any metal keys or pads. Flutes of this era could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument; the wooden

*

*

Music Technology in Education

Music Technology Resources

Detailed history of electronic instruments and electronic music technology at '120 years of Electronic Music'

{{Music topics Music technology, Music history Musical instruments

Mechanical music technology is the use of any device, mechanism, machine or tool by a musician or composer to make or perform music; to

Mechanical music technology is the use of any device, mechanism, machine or tool by a musician or composer to make or perform music; to compose

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

*Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include v ...

, notate, play back or record songs or pieces; or to analyze or edit music. The earliest known applications of technology to music was prehistoric peoples' use of a tool to hand-drill holes in bones to make simple flutes. Ancient Egyptians developed stringed instruments, such as harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

s, lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

s and lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

s, which required making thin strings and some type of peg system for adjusting the pitch of the strings. Ancient Egyptians also used wind instruments such as double clarinet

The term double clarinet refers to any of several woodwind instruments consisting of two parallel pipes made of cane, bird bone, or metal, played simultaneously, with a single reed for each. Commonly, there are five or six tone holes in each pipe ...

s and percussion instruments such as cymbals

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

. In Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, instruments included the double-reed aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

and the lyre. Numerous instruments are referred to in the Bible, including the horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

, pipe, lyre, harp, and bagpipe

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Nor ...

. During Biblical times, the cornet, flute, horn, organ, pipe, and trumpet were also used. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, hand-written music notation

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

was developed to write down the notes of religious Plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. ...

melodies; this notation enabled the Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

to disseminate the same chant melodies across its entire empire.

During the Renaissance music

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the Renaissance era as it is understood in other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century '' ars nova'', the Tr ...

era, the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

was invented, which made it much easier to mass-produce music (which had previously been hand-copied). This helped to spread musical styles more quickly and across a larger area. During the Baroque era

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including th ...

(1600–1750), technologies for keyboard instruments developed, which led to improvements in the designs of pipe organs and harpsichords, and the development of a new keyboard instrument in about 1700, the piano. In the Classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

(1750–1820), Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

added new instruments to the orchestra to create new sounds, such as the piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

, contrabassoon

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Differences from the bassoon

The reed is consi ...

, trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

s, and untuned percussion

An unpitched percussion instrument is a percussion instrument played in such a way as to produce sounds of indeterminate pitch, or an instrument normally played in this fashion.

Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to ...

in his Ninth Symphony. During the Romantic music

Romantic music is a stylistic movement in Western Classical music associated with the period of the 19th century commonly referred to as the Romantic era (or Romantic period). It is closely related to the broader concept of Romanticism—the ...

era (c. 1810 to 1900), one of the key ways that new compositions became known to the public was by the sales of relatively inexpensive sheet music

Sheet music is a handwritten or printed form of musical notation that uses List of musical symbols, musical symbols to indicate the pitches, rhythms, or chord (music), chords of a song or instrumental Musical composition, musical piece. Like ...

, which amateur middle class music lovers would perform at home on their piano or other instruments. In the 19th century, new instruments such as piston valve

A "piston valve" is a device used to control the motion of a fluid along a tube or pipe by means of the linear motion of a piston within a chamber or cylinder.

Examples of piston valves are:

* The valves used in many brass instruments

* The va ...

-equipped cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

s, saxophones, euphonium

The euphonium is a medium-sized, 3 or 4-valve, often compensating, conical-bore, tenor-voiced brass instrument that derives its name from the Ancient Greek word ''euphōnos'', meaning "well-sounding" or "sweet-voiced" ( ''eu'' means "well" ...

s, and Wagner tuba

The Wagner tuba is a four-valve brass instrument named after and commissioned by Richard Wagner. It combines technical features of both standard tubas and French horns, though despite its name, the Wagner tuba is more similar to the latter, and ...

s were added to the orchestra. Many of the mechanical innovations developed for instruments in the 19th century, notably on the piano, brass and woodwinds continued to be used in the 20th and early 21st century.

History

Prehistoric eras

Findings from

Findings from paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

archaeology sites suggest that prehistoric people used carving and piercing tools to create instruments. Archeologists have found Paleolithic flutes

During regular archaeological excavations, several flutes that date to the European Upper Paleolithic were discovered in caves in the Swabian Alb region of Germany. Dated and tested independently by two laboratories, in England and Germany, the a ...

carved from bones in which lateral holes have been pierced. The Divje Babe flute

The Divje Babe flute is a cave bear femur pierced by spaced holes that was unearthed in 1995 during systematic archaeological excavations led by the Institute of Archaeology of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, at ...

, carved from a cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word "cave" and the scientific name ' ...

femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

, is thought to be at least 40,000 years old. Instruments such as the seven-holed flute and various types of stringed instruments

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the st ...

, such as the Ravanahatha

A ravanahatha (variant names: ''ravanhatta'', ''rawanhattha'', ''ravanastron'', ''ravana hasta veena'') is an ancient bowed, stringed instrument, used in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and surrounding areas. It has been suggested as an ancestor of t ...

, have been recovered from the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

sites. India has one of the oldest musical traditions in the world—references to Indian classical music

Indian classical music is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as '' Hindustani'' and the South Indian expression known as '' Carnatic''. These traditions were not ...

(''marga'') are found in the Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

, ancient scriptures of the Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

tradition. The earliest and largest collection of prehistoric musical instruments was found in China and dates back to between 7000 and 6600 BC.

Ancient Egypt

In

In prehistoric Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

, music and chanting were commonly used in magic and rituals, and small shells were used as whistle

A whistle is an instrument which produces sound from a stream of gas, most commonly air. It may be mouth-operated, or powered by air pressure, steam, or other means. Whistles vary in size from a small slide whistle or nose flute type to a larg ...

s. Evidence of Egyptian musical instruments dates to the Predynastic period

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

, when funerary chants played an important role in Egyptian religion and were accompanied by clappers and possibly the flute. The most reliable evidence of instrument technologies dates from the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

, when technologies for constructing harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

s, flutes and double clarinet

The term double clarinet refers to any of several woodwind instruments consisting of two parallel pipes made of cane, bird bone, or metal, played simultaneously, with a single reed for each. Commonly, there are five or six tone holes in each pipe ...

s were developed. Percussion instruments, lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

s and lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

s were used by the Middle Kingdom. Metal cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s were used by ancient Egyptians. In the early 21st century, interest in the music of the pharaonic period began to grow, inspired by the research of such foreign-born musicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some mu ...

s as Hans Hickmann

Hans Robert Hermann Hickmann (b. Roßlau, Germany, May 19, 1908; d. Blandford Forum, England, September 4, 1968) was an eminent German Musicology, musicologist. He lived in Egypt and specialized in the music and organology of Ancient Egypt, and sur ...

. By the early 21st century, Egyptian musicians and musicologists led by the musicology professor Khairy El-Malt at Helwan University

Helwan University is a public university based in Helwan, Egypt, which is part of Greater Cairo on over . It comprises 23 faculties and two higher institutes in addition to 50 research centers.

Overview

Helwan University is a member of the E ...

in Cairo had begun to reconstruct musical instruments of Ancient Egypt, a project that is ongoing.

Asian cultures

TheIndus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

has sculptures that show old musical instruments, like the seven-holed flute. Various types of stringed instruments and drums have been recovered from Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

and Mohenjo Daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Mortimer Wheeler

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales an ...

.

References in the Bible

According to the

According to the Scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

, Jubal was the father of harpists and organists (Gen. 4:20–21). The harp was among the chief instruments and the favorite of David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, and it is referred to more than fifty times in the Bible. It was used at both joyful and mournful ceremonies, and its use was "raised to its highest perfection under David" (1 Sam. 16:23). Lockyer adds that "It was the sweet music of the harp that often dispossessed Saul of his melancholy (1 Sam. 16:14–23; 18:10–11).Lockyer, Herbert Jr. ''All the Music of the Bible'', Hendrickson Publ. (2004) When the Jews were captive in Babylon they hung their harps up and refused to use them while in exile, earlier being part of the instruments used in the Temple (1 Kgs. 10:12). Another stringed instrument of the harp class, and one also used by the ancient Greeks, was the lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

. A similar instrument was the lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

, which had a large pear-shaped body, long neck, and fretted fingerboard with head screws for tuning. Coins displaying musical instruments, the Bar Kochba Revolt coinage

Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage were coins issued by the Judaean rebel state, headed by Simon Bar Kokhba, during the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire of 132-135 CE.

During the Revolt, large quantities of coins were issued in silver and copp ...

, were issued by the Jews during the Second Jewish Revolt against the Roman Empire of 132–135 AD.

In addition there was the

In addition there was the psaltery

A psaltery ( el, ψαλτήρι) (or sawtry, an archaic form) is a fretboard-less box zither (a simple chordophone) and is considered the archetype of the zither and dulcimer; the harp, virginal, harpsichord and clavichord were also inspired by ...

, another stringed instrument which is referred to almost thirty times in Scripture. According to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

, it had twelve strings and was played with a quill

A quill is a writing tool made from a moulted flight feather (preferably a primary wing-feather) of a large bird. Quills were used for writing with ink before the invention of the dip pen, the metal- nibbed pen, the fountain pen, and, eventually ...

, not with the hand. Another writer suggested that it was like a guitar, but with a flat triangular form and strung from side to side.

Among the wind instruments used in the biblical period were the cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

, wood flute, horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

, organ, pipe

Pipe(s), PIPE(S) or piping may refer to:

Objects

* Pipe (fluid conveyance), a hollow cylinder following certain dimension rules

** Piping, the use of pipes in industry

* Smoking pipe

** Tobacco pipe

* Half-pipe and quarter pipe, semi-circula ...

, and early trumpet. There were also silver trumpets and the double oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

. Werner concludes that from the measurements taken of the trumpets on the Arch of Titus

The Arch of Titus ( it, Arco di Tito; la, Arcus Titi) is a 1st-century AD honorific arch, located on the Via Sacra, Rome, just to the south-east of the Roman Forum. It was constructed in 81 AD by the Roman emperor, Emperor Domitian shortly aft ...

in Rome and from coins, that "the trumpets were very high pitched with thin body and shrill sound." He adds that in ''War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness

''The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness'', also known as War Rule, Rule of War and the War Scroll, is a manual for military organization and strategy that was discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls. The manuscript was among the ...

'', a manual for military organization and strategy discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

, these trumpets "appear clearly capable of regulating their pitch pretty accurately, as they are supposed to blow rather complicated signals in unison."Werner, Eric. ''The Sacred Bridge'', Columbia Univ. Press (1984) Whitcomb writes that the pair of silver trumpets were fashioned according to Mosaic law

The Law of Moses ( he, תֹּורַת מֹשֶׁה ), also called the Mosaic Law, primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. The law revealed to Moses by God.

Terminology

The Law of Moses or Torah of Moses (Hebrew ...

and were probably among the trophies which the Emperor Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a milit ...

brought to Rome when he conquered Jerusalem. She adds that on the Arch raised to the victorious Titus, "there is a sculptured relief of these trumpets, showing their ancient form. (see photo)Whitcomb, Ida Prentice. ''Young People's Story of Music'', Dodd, Mead & Co. (1928)

The flute was commonly used for festal and mourning occasions, according to Whitcomb. "Even the poorest Hebrew was obliged to employ two flute-players to perform at his wife's funeral." The shofar

A shofar ( ; from he, שׁוֹפָר, ) is an ancient musical horn typically made of a ram's horn, used for Jewish religious purposes. Like the modern bugle, the shofar lacks pitch-altering devices, with all pitch control done by varying the ...

(the horn of a ram) is still used for special liturgical purposes such as the Jewish New Year

Rosh HaShanah ( he, רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה, , literally "head of the year") is the Jewish New Year. The biblical name for this holiday is Yom Teruah (, , lit. "day of shouting/blasting") It is the first of the Jewish High Holy Days (, , ...

services in orthodox communities. As such, it is not considered a musical instrument but an instrument of theological symbolism which has been intentionally kept to its primitive character. In ancient times it was used for warning of danger, to announce the new moon or beginning of Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, commanded by God to be kept as a holy day of rest, as G ...

, or to announce the death of a notable. "In its strictly ritual usage it carried the cries of the multitude to God," writes Werner.

Among the percussion instruments were bells, cymbals

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

, sistrum

A sistrum (plural: sistra or Latin sistra; from the Greek ''seistron'' of the same meaning; literally "that which is being shaken", from ''seiein'', "to shake") is a musical instrument of the percussion family, chiefly associated with ancient ...

, tabret, hand drums, and tambourines

The tambourine is a musical instrument in the percussion family consisting of a frame, often of wood or plastic, with pairs of small metal jingles, called " zills". Classically the term tambourine denotes an instrument with a drumhead, though ...

. The tabret, or timbrel, was a small hand-drum used for festive occasions, and was considered a woman's instrument. In modern times it was often used by the Salvation Army. According to the Bible, when the children of Israel came out of Egypt and crossed the Red Sea, ''"Miriam

Miriam ( he, מִרְיָם ''Mīryām'', lit. 'Rebellion') is described in the Hebrew Bible as the daughter of Amram and Jochebed, and the older sister of Moses and Aaron. She was a prophetess and first appears in the Book of Exodus.

The Tor ...

took a timbrel in her hands; and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dance."''

Ancient Greece

In

In Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, instruments in all music can be divided into three categories, based on how sound is produced: string, wind, and percussion. The following were among the instruments used in the music of ancient Greece:

*the lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

: a strummed and occasionally plucked string instrument

Plucked string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by plucking the strings. Plucking is a way of pulling and releasing the string in such a way as to give it an impulse that causes the string to vibrate. Plucki ...

, essentially a hand-held zither

Zithers (; , from the Greek word ''cithara'') are a class of stringed instruments. Historically, the name has been applied to any instrument of the psaltery family, or to an instrument consisting of many strings stretched across a thin, flat bo ...

built on a tortoise-shell frame, generally with seven or more strings tuned to the notes of one of the modes. The lyre was used to accompany others or even oneself for recitation and song.

*the kithara

The kithara (or Latinized cithara) ( el, κιθάρα, translit=kithāra, lat, cithara) was an ancient Greek musical instrument in the yoke lutes family. In modern Greek the word ''kithara'' has come to mean "guitar", a word which etymologic ...

, also a strummed string instrument, more complicated than the lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

. It had a box-type frame with strings stretched from the cross-bar at the top to the sounding box

A sound box or sounding box (sometimes written soundbox) is an open chamber in the body of a musical instrument which modifies the sound of the instrument, and helps transfer that sound to the surrounding air. Objects respond more strongly to vib ...

at the bottom; it was held upright and played with a plectrum

A plectrum is a small flat tool used for plucking or strumming of a stringed instrument. For hand-held instruments such as guitars and mandolins, the plectrum is often called a pick and is held as a separate tool in the player's hand. In harpsic ...

. The strings were tunable by adjusting wooden wedges along the cross-bar.

* the ''aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

'', usually double, consisting of two double-reed (like an oboe) pipes, not joined but generally played with a mouth-band to hold both pipes steadily between the player's lips. Modern reconstructions indicate that they produced a low, clarinet-like sound. There is some confusion about the exact nature of the instrument; alternate descriptions indicate single-reeds instead of double reeds.

* the Pan pipes

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have bee ...

, also known as panflute and syrinx

In classical Greek mythology, Syrinx (Greek Σύριγξ) was a nymph and a follower of Artemis, known for her chastity. Pursued by the amorous god Pan, she ran to a river's edge and asked for assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, sh ...

(Greek συριγξ), (so-called for the nymph who was changed into a reed in order to hide from Pan) is an ancient musical instrument based on the principle of the stopped pipe, consisting of a series of such pipes of gradually increasing length, tuned (by cutting) to a desired scale. Sound is produced by blowing across the top of the open pipe (like blowing across a bottle top).

* the hydraulis

The water organ or hydraulic organ ( el, ὕδραυλις) (early types are sometimes called hydraulos, hydraulus or hydraula) is a type of pipe organ blown by air, where the power source pushing the air is derived by water from a natural sourc ...

, a keyboard instrument, the forerunner of the modern organ. As the name indicates, the instrument used water to supply a constant flow of pressure to the pipes. Two detailed descriptions have survived: that of Vitruvius and Heron of Alexandria. These descriptions deal primarily with the keyboard mechanism and with the device by which the instrument was supplied with air. A well-preserved model in pottery was found at Carthage in 1885. Essentially, the air to the pipes that produce the sound comes from a wind-chest connected by a pipe to a dome; air is pumped in to compress water, and the water rises in the dome, compressing the air, and causing a steady supply of air to the pipes.

In the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', Virgil makes numerous references to the trumpet. The lyre, kithara, aulos, hydraulis (water organ) and trumpet all found their way into the music of ancient Rome

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

.

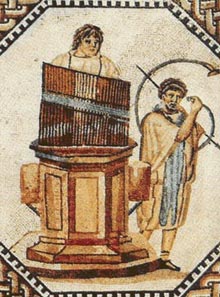

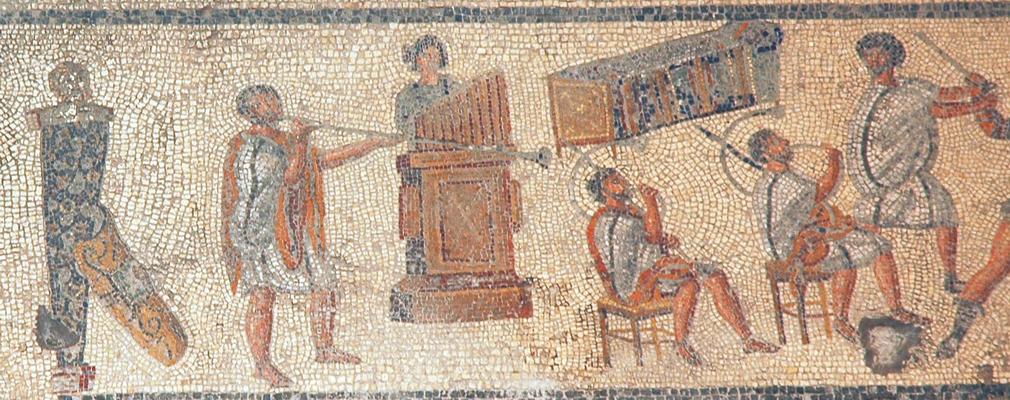

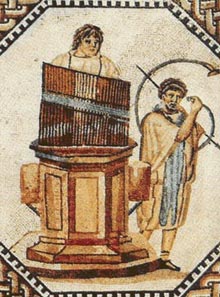

Ancient Rome

Roman art

The art of Ancient Rome, and the territories of its Republic and later Empire, includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be mi ...

depicts various woodwinds, "brass", percussion and stringed instruments

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the st ...

. Roman-style instruments are found in parts of the Empire where they did not originate, and indicate that music was among the aspects of Roman culture that spread throughout the provinces.

Roman instruments include:

*The Roman ''tuba'' was a long, straight bronze trumpet with a detachable, conical mouthpiece. Extant examples are about 1.3 metres long, and have a cylindrical bore from the mouthpiece to the point where the bell flares abruptly, similar to the modern straight trumpet seen in presentations of 'period music'. Since there were no valves, the ''tuba'' was capable only of a single overtone

An overtone is any resonant frequency above the fundamental frequency of a sound. (An overtone may or may not be a harmonic) In other words, overtones are all pitches higher than the lowest pitch within an individual sound; the fundamental i ...

series. In the military, it was used for "bugle call

A bugle call is a short tune, originating as a military signal announcing scheduled and certain non-scheduled events on a military installation, battlefield, or ship. Historically, bugles, drums, and other loud musical instruments were used fo ...

s". The ''tuba'' is also depicted in art such as mosaics

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

accompanying games ''(ludi

''Ludi'' (Latin plural) were public games held for the benefit and entertainment of the Roman people (''populus Romanus''). ''Ludi'' were held in conjunction with, or sometimes as the major feature of, Roman religious festivals, and were also ...

)'' and spectacle events.

*The '' cornu'' (Latin "horn") was a long tubular metal wind instrument that curved around the musician's body, shaped rather like an uppercase ''G''. It had a conical bore (again like a French horn) and a conical mouthpiece. It may be hard to distinguish from the ''buccina

A buccina ( lat, buccina) or bucina ( lat, būcina, link=no), anglicized buccin or bucine, is a brass instrument that was used in the ancient Roman army, similar to the cornu. An ''aeneator'' who blew a buccina was called a "buccinator" or "buci ...

''. The ''cornu'' was used for military signals and on parade. The ''cornicen

A ''cornicen'' (plural ''cornicines'') was a junior officer in the Roman army. The ''cornicens job was to signal salutes to officers and sound orders to the legions. The ''cornicines'' played the '' cornu'' (making him an ''aeneator''). ''Cornici ...

'' was a military signal officer who translated orders into calls. Like the ''tuba'', the ''cornu'' also appears as accompaniment for public events and spectacle entertainments.

*The ''tibia'' (Greek ''aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

– αὐλός''), usually double, had two double-reed (as in a modern oboe) pipes, not joined but generally played with a mouth-band ''capistrum'' to hold both pipes steadily between the player's lips.

*The ''askaules Askaules (Greek language, Greek: ἄσκαυλος from ''ἀσκός'' "bag" and ''αὐλός'' "pipe"), probably the Greek word for bag-piper, although there is no documentary authority for its use.

History

Neither *''ἄσκαυλης'' nor ''� ...

'' – a bagpipe

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Nor ...

.

*Versions of the modern flute and panpipes

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

.

*The lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

, borrowed from the Greeks, was not a harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

, but instead had a sounding body of wood or a tortoise shell covered with skin, and arms of animal horn or wood, with strings stretched from a cross bar to the sounding body.

*The ''cithara

The kithara (or Latinized cithara) ( el, κιθάρα, translit=kithāra, lat, cithara) was an ancient Greek musical instrument in the yoke lutes family. In modern Greek the word ''kithara'' has come to mean "guitar", a word which etymologic ...

'' was the premier musical instrument of ancient Rome and was played both in popular and elevated forms of music. Larger and heavier than a lyre, the cithara was a loud, sweet and piercing instrument with precision tuning ability.

*The lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

(pandura

The pandura ( grc, πανδοῦρα, ''pandoura'') or pandore, an ancient string instrument, belonged in the broad class of the lute and guitar instruments. Akkadians played similar instruments from the 3rd millennium BC. Ancient Greek artwork d ...

or monochord

A monochord, also known as sonometer (see below), is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument, involving one (mono-) string ( chord). The term ''monochord'' is sometimes used as the class-name for any musical stringed instrument h ...

) was known by several names among the Greeks and Romans. In construction, the lute differs from the lyre in having fewer strings stretched over a solid neck or fret-board, on which the strings can be stopped to produce graduated notes. Each lute string is thereby capable of producing a greater range of notes than a lyre string. Although long-necked lutes are depicted in art from Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

as early as 2340–2198 BC, and also occur in Egyptian iconography, the lute in the Greco-Roman world was far less common than the lyre and cithara. The lute of the medieval West is thought to owe more to the Arab oud

, image=File:oud2.jpg

, image_capt=Syrian oud made by Abdo Nahat in 1921

, background=

, classification=

* String instruments

*Necked bowl lutes

, hornbostel_sachs=321.321-6

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded with a plectrum

, ...

, from which its name derives (''al ʿūd'').

* The hydraulic pipe organ ''(hydraulis

The water organ or hydraulic organ ( el, ὕδραυλις) (early types are sometimes called hydraulos, hydraulus or hydraula) is a type of pipe organ blown by air, where the power source pushing the air is derived by water from a natural sourc ...

)'', which worked by water pressure, was "one of the most significant technical and musical achievements of antiquity". Essentially, the air to the pipes that produce the sound comes from a mechanism of a wind-chest connected by a pipe to a dome; air is pumped in to compress water, and the water rises in the dome, compressing the air and causing a steady supply to reach the pipes (also see Pipe organ#History). The ''hydraulis'' accompanied gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

contests and events in the arena, as well as stage performances.

*Variations of a hinged wooden or metal device called a scabellum

A scabellum, Latin word from ancient Greek ''krupalon'' or ''krupezon'', is a percussion instrument, a kind of Clapper used in ancient Rome and Greece.

It is worn like a sandal

Sandals are an open type of footwear, consisting of a sole h ...

used to beat time. Also, there were various rattles, bells and tambourine

The tambourine is a musical instrument in the percussion family consisting of a frame, often of wood or plastic, with pairs of small metal jingles, called "zills". Classically the term tambourine denotes an instrument with a drumhead, though ...

s.

*Drum and percussion instruments like timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

and castanets, the Egyptian sistrum, and brazen pans, served various musical and other purposes in ancient Rome, including backgrounds for rhythmic dance, celebratory rites like those of the Bacchantes and military uses.

*The sistrum

A sistrum (plural: sistra or Latin sistra; from the Greek ''seistron'' of the same meaning; literally "that which is being shaken", from ''seiein'', "to shake") is a musical instrument of the percussion family, chiefly associated with ancient ...

was a rattle consisting of rings strung across the cross-bars of a metal frame, which was often used for ritual purposes.

*''Cymbala'' (Lat. plural of ''cymbalum'', from the Greek ''kymbalon'') were small cymbals: metal discs with concave centres and turned rims, used in pairs which were clashed together.

Middle Ages

During the

During the Medieval Music

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and followed by the Renaissance ...

era (476 to 1400) the plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. ...

tunes used by monks for religious songs were primarily monophonic (a single melody line, with no harmony parts) and transmitted by oral tradition ("by ear"). The earliest Medieval music did not have any kind of notational system for writing down melodies. As Rome tried to centralize the various chants across vast distances of its empire, which stretched from Europe to North Africa, a form of music notation was needed to write down the melodies. So long as the church had to rely on teaching people chant melodies "by ear", it limited the number of people who could be taught. As well, when songs are learned by ear, variations and changes naturally slip in.

Various signs written above the chant texts, called ''neumes

A neume (; sometimes spelled neum) is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation.

The earliest neumes were inflective marks that indicated the general shape but not ne ...

'' were introduced. These little signs indicated to the singer whether the melody went up in pitch or down in pitch. By the ninth century, it was firmly established as the primary method of musical notation. The next development in musical notation was "heighted neumes", in which neumes were carefully placed at different heights in relation to each other. This allowed the neumes to give a rough indication of the size of a given interval (e.g., a small interval like a tone or a large interval like a sixth) as well as the direction (up in pitch or down in pitch).

At first the little dots were just placed in the space about the words. However, this method made it hard to determine what pitch a song started on, or when a song was returning to the same pitch. This quickly led to one or two lines, each representing a particular note, being placed on the music with all of the neumes relating back to them, and being placed on or above the lines. The line or lines acted as a reference point to help the singer gauge which notes were higher or lower. At first, these lines had no particular meaning and instead had a letter placed at the beginning indicating which note was represented. However, the lines indicating middle C and the F a fifth below slowly became most common. The completion of the four-line staff is usually credited to Guido d' Arezzo (c. 1000–1050), one of the most important musical theorists of the Middle Ages. The neumatic notational system, even in its fully developed state, did not clearly define any kind of rhythm for the singing of notes. Singers were expected to be able to improvise the rhythm, using established traditions and norms.

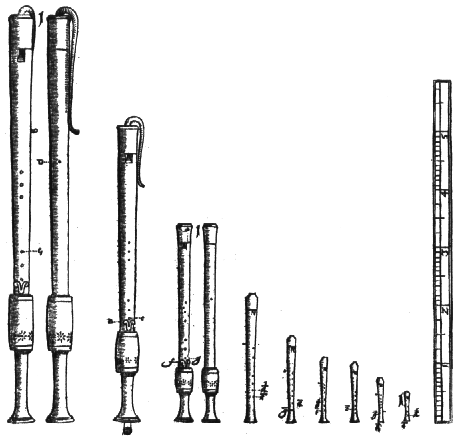

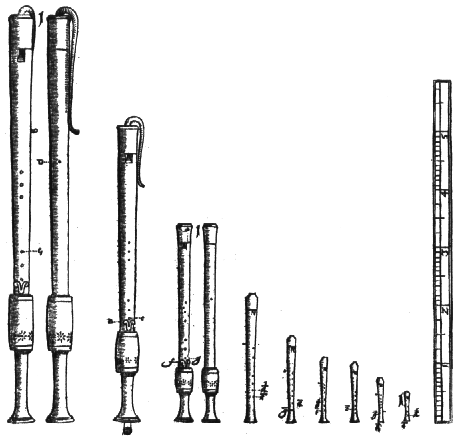

Instruments used to perform medieval music include the early flute, which was made of wood and which did not have any metal keys or pads. Flutes of this era could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument; the wooden

Instruments used to perform medieval music include the early flute, which was made of wood and which did not have any metal keys or pads. Flutes of this era could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument; the wooden recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

and the related instrument called the gemshorn

The gemshorn is an instrument of the ocarina family that was historically made from the horn of a chamois, goat, or other suitable animal.

; and the pan flute

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

. Medieval music used many plucked string instrument

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the ...

s like the lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

, mandore

Mandore is a suburb Historical town located 9 km north of Jodhpur city, in the Indian state of Rajasthan.

History

Mandore is an ancient town, and was the seat of the Pratiharas of Mandavyapura, who ruled the region in the 6th century CE ...

, gittern

The gittern was a relatively small gut-strung, round-backed instrument that first appears in literature and pictorial representation during the 13th century in Western Europe (Iberian Peninsula, Italy, France, England). It is usually depicted pl ...

and psaltery

A psaltery ( el, ψαλτήρι) (or sawtry, an archaic form) is a fretboard-less box zither (a simple chordophone) and is considered the archetype of the zither and dulcimer; the harp, virginal, harpsichord and clavichord were also inspired by ...

. The dulcimers

The word dulcimer refers to two families of musical string instruments.

Hammered dulcimers

The word ''dulcimer'' originally referred to a trapezoidal zither similar to a psaltery whose many strings are struck by handheld "hammers". Variants of th ...

, similar in structure to the psaltery

A psaltery ( el, ψαλτήρι) (or sawtry, an archaic form) is a fretboard-less box zither (a simple chordophone) and is considered the archetype of the zither and dulcimer; the harp, virginal, harpsichord and clavichord were also inspired by ...

and zither

Zithers (; , from the Greek word ''cithara'') are a class of stringed instruments. Historically, the name has been applied to any instrument of the psaltery family, or to an instrument consisting of many strings stretched across a thin, flat bo ...

, were originally plucked, but became struck by hammers in the 14th century after the arrival of new technology that made metal strings possible.

The bowed lyra

Lyra (; Latin for lyre, from Greek ''λύρα'') is a small constellation. It is one of the 48 listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and is one of the modern 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union. Lyra was ...

of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

was the first recorded European bowed string instrument. The Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih

Abu'l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh ( ar, ابوالقاسم عبیدالله ابن خرداذبه; 820/825–913), commonly known as Ibn Khordadbeh (also spelled Ibn Khurradadhbih; ), was a high-ranking Persian bureaucrat and ...

of the 9th century (d. 911) cited the Byzantine lyra

The Byzantine lyra or lira ( gr, λύρα) was a medieval bowed string musical instrument in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. In its popular form, the lyra was a pear-shaped instrument with three to five strings, held upright and played by ...

as a bowed instrument equivalent to the Arab rabāb

The ''rebab'' ( ar, ربابة, ''rabāba'', variously spelled ''rebap'', ''rubob'', ''rebeb'', ''rababa'', ''rabeba'', ''robab'', ''rubab'', ''rebob'', etc) is the name of several related string instruments that independently spread via I ...

and typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the ''urghun'' (organ), ''shilyani'' (probably a type of harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

or lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

) and the ''salandj'' (probably a bagpipe

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Nor ...

). The hurdy-gurdy

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by a hand-crank-turned, rosined wheel rubbing against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar to those of a vio ...

was a mechanical violin using a rosined wooden wheel attached to a crank to "bow" its strings. Instruments without sound boxes like the jaw harp were also popular in the time. Early versions of the organ, fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

(or vielle

The vielle is a European bowed stringed instrument used in the medieval period, similar to a modern violin but with a somewhat longer and deeper body, three to five gut strings, and a leaf-shaped pegbox with frontal tuning pegs, sometimes with a ...

), and trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

(called the sackbut

The term sackbut refers to the early forms of the trombone commonly used during the Renaissance music, Renaissance and Baroque music, Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of th ...

) existed in the medieval era.

Renaissance

TheRenaissance music

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the Renaissance era as it is understood in other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century '' ars nova'', the Tr ...

era (c. 1400 to 1600) saw the development of many new technologies that affected the performance and distribution of songs and musical pieces. Around 1450, the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

was invented, which made printed sheet music

Sheet music is a handwritten or printed form of musical notation that uses List of musical symbols, musical symbols to indicate the pitches, rhythms, or chord (music), chords of a song or instrumental Musical composition, musical piece. Like ...

much less expensive and easier to mass-produce (prior to the invention of the printing press, all notated music was laboriously hand-copied). The increased availability of printed sheet music helped to spread musical styles more quickly and across a larger geographic area. One limiting factor to the wider dissemination of musical styles was that monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s, nuns

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

, aristocrat

The aristocracy is historically associated with "hereditary" or "ruling" social class. In many states, the aristocracy included the upper class of people (aristocrats) with hereditary rank and titles. In some, such as ancient Greece, ancient Ro ...

s and professional musicians and singers were among the few people who could read music.

Mechanical plate engraving was developed in the late sixteenth century. Although plate engraving had been used since the early fifteenth century for creating visual art and maps, it was not applied to music until 1581. In this method, a mirror image of a complete page of music was engraved onto a metal plate. Ink was then applied to the grooves, and the music print was transferred onto paper. Metal plates could be stored and reused, which made this method an attractive option for music engravers. Copper was the initial metal of choice for early plates, but by the eighteenth century pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. Copper and antimony (and in antiquity lead) act as hardeners, but lead may be used in lower grades of ...

became the standard material due to its malleability and lower cost.

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance. Some instruments used during the Renaissance were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously in the medieval era. Brass instruments in the Renaissance were traditionally played by professionals who were part of guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s, which kept playing techniques secret. Some of the more common brass instruments that were played included:

*Slide trumpet

The slide trumpet is an early type of trumpet fitted with a movable section of telescopic tubing, similar to the slide of a trombone. Eventually, the slide trumpet evolved into the sackbut, which evolved into the modern-day trombone. The key dif ...

: Similar to the trombone of today except that instead of a section of the body sliding, only a small part of the body near the mouthpiece and the mouthpiece itself is stationary.

*Cornett

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is an early wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. It was used in what are now called alta capellas or wind ensembles. It is not to be confused wi ...

: Made of wood and was played like the recorder, but blown like a trumpet.

*Trumpet: Early trumpets from the Renaissance era had no valves, and were limited to the tones present in the overtone series

A harmonic series (also overtone series) is the sequence of harmonics, musical tones, or pure tones whose frequency is an integer multiple of a ''fundamental frequency''.

Pitched musical instruments are often based on an acoustic resonator su ...

. This limited the types of melodies that Renaissance trumpets could play. They were also made in different sizes.

*Sackbut

The term sackbut refers to the early forms of the trombone commonly used during the Renaissance music, Renaissance and Baroque music, Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of th ...

: A different name for the trombone, which replaced the slide trumpet by the middle of the 15th century

Stringed instruments included:

*Viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

: This hollow, wooden stringed instrument, developed in the 15th century, commonly had six strings. It was usually played with a bow.

*Lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

: Its construction is similar to a small harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

, although instead of being plucked, it is strummed with a plectrum (or "pick"). Its strings varied in quantity from four, seven, and ten, depending on the era. It was played with the right hand, while the left hand silenced the notes that were not desired. Some newer lyres were modified to be played with a bow.

*Hurdy-gurdy

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by a hand-crank-turned, rosined wheel rubbing against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar to those of a vio ...

: (Also known as the "wheel fiddle"), in which the strings are sounded by a wheel which the strings pass over. Its functionality can be compared to that of a mechanical violin, in that its bow (wheel) is turned by a crank. Its distinctive sound is mainly because of its "drone strings" which provide a constant pitch similar in their sound to that of bagpipes.

*Gittern

The gittern was a relatively small gut-strung, round-backed instrument that first appears in literature and pictorial representation during the 13th century in Western Europe (Iberian Peninsula, Italy, France, England). It is usually depicted pl ...

and mandore

Mandore is a suburb Historical town located 9 km north of Jodhpur city, in the Indian state of Rajasthan.

History

Mandore is an ancient town, and was the seat of the Pratiharas of Mandavyapura, who ruled the region in the 6th century CE ...

: these instruments were used throughout Europe. They were the forerunners of modern plucked string instruments including the mandolin

A mandolin ( it, mandolino ; literally "small mandola") is a stringed musical instrument in the lute family and is generally plucked with a pick. It most commonly has four courses of doubled strings tuned in unison, thus giving a total of 8 ...

and acoustic guitar.

Percussion instruments included:

*Tambourine

The tambourine is a musical instrument in the percussion family consisting of a frame, often of wood or plastic, with pairs of small metal jingles, called "zills". Classically the term tambourine denotes an instrument with a drumhead, though ...

: The tambourine is a frame drum equipped with jingles that produce a sound when the drum is struck.

* Jew's harp: An instrument that produces sound using shapes of the mouth and attempting to pronounce different vowels with ones mouth.

Woodwind instruments included:

*Shawm

The shawm () is a Bore_(wind_instruments)#Conical_bore, conical bore, double-reed woodwind instrument made in Europe from the 12th century to the present day. It achieved its peak of popularity during the medieval and Renaissance periods, after ...

: A typical shawm is keyless and about a foot long, with seven finger holes and a thumb hole. The pipes were commonly made of wood and more expensive models had carvings and decorations on them. It was the most popular double reed

A double reed is a type of reed used to produce sound in various wind instruments. In contrast with a single reed instrument, where the instrument is played by channeling air against one piece of cane which vibrates against the mouthpiece and c ...

instrument of the Renaissance period; it was commonly used in the streets with drums and trumpets because of its brilliant, piercing, and often deafening sound. To play the shawm a person puts the entire reed in their mouth, puffs out their cheeks, and blows into the pipe whilst breathing through their nose.

*

*Reed pipe

A reed pipe (also referred to as a ''lingual'' pipe) is an organ pipe that is sounded by a vibrating brass strip known as a ''reed''. Air under pressure (referred to as ''wind'') is directed towards the reed, which vibrates at a specific pitc ...

: Made from a single short length of cane with a mouthpiece, four or five finger holes, and reed fashioned from it. The reed is made by cutting out a small tongue, but leaving the base attached. It is the early predecessor of the saxophone and the clarinet.

*Hornpipe

The hornpipe is any of several dance forms played and danced in Britain and Ireland and elsewhere from the 16th century until the present day. The earliest references to hornpipes are from England with Hugh Aston's Hornepype of 1522 and others r ...

: Same as reed pipe but with a bell at the end.

*Bagpipe

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Nor ...

/Bladderpipe: It used a bag made out of sheep or goat skin that would provide air pressure for a pipe. When its player takes a breath, the player only needs to squeeze the bag tucked underneath their arm to continue the tone. The mouth pipe has a simple round piece of leather hinged on to the bag end of the pipe and acts like a non-return valve. The reed is located inside the long metal mouthpiece, known as a bocal.

*Panpipe

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

: Designed to have sixteen wooden tubes with a stopper at one end and open on the other. Each tube is a different size (thereby producing a different tone), giving it a range of an octave and a half. The player can then place their lips against the desired tube and blow across it.

*Transverse flute

A transverse flute or side-blown flute is a flute which is held horizontally when played. The player blows across the embouchure hole, in a direction perpendicular to the flute's body length.

Transverse flutes include the Western concert flute ...

: The transverse flute is similar to the modern flute with a mouth hole near the stoppered end and finger holes along the body. The player blows in the side and holds the flute to the right side.

*Recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

: It uses a whistle mouth piece, which is a beak shaped mouth piece, as its main source of sound production. It is usually made of wood, with seven finger holes and a thumb hole.

Baroque

During the Baroque era of music (ca. 1600–1750), technologies for keyboard instruments developed, which led to improvements in the designs ofpipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks ...

s and harpsichord

A harpsichord ( it, clavicembalo; french: clavecin; german: Cembalo; es, clavecín; pt, cravo; nl, klavecimbel; pl, klawesyn) is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. This activates a row of levers that turn a trigger mechanism ...

s, and to the development of the first pianos. During the Baroque period, organ builders developed new types of pipes and reeds that created new tonal colors (timbres and sounds). Organ builders fashioned new stops that imitated various instruments, such as the viola da gamba

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

stop. The Baroque period is often thought of as organ building's "golden age," as virtually every important refinement to the instrument was brought to a peak. Builders such as Arp Schnitger

Arp Schnitger (2 July 164828 July 1719 (buried)) was an influential Northern German organ builder. Considered the most paramount manufacturer of his time, Schnitger built or rebuilt over 150 organs. He was primarily active in Northern Europe, es ...

, Jasper Johannsen, Zacharias Hildebrandt

Zacharias Hildebrandt (1688, Münsterberg, Silesia – 11 October 1757, Dresden, Saxony) was a German organ builder. In 1714 his father Heinrich Hildebrandt, a cartwright master, apprenticed him to the famous organbuilder Gottfried Silberman ...

and Gottfried Silbermann

Gottfried Silbermann (January 14, 1683 – August 4, 1753) was a German builder of keyboard instruments. He built harpsichords, clavichords, organs, and fortepianos; his modern reputation rests mainly on the latter two.

Life

Very little is know ...

constructed instruments that displayed both exquisite craftsmanship and beautiful sound. These organs featured well-balanced mechanical key actions, giving the organist precise control over the pipe speech. Schnitger's organs featured particularly distinctive reed timbres and large Pedal

A pedal (from the Latin '' pes'' ''pedis'', "foot") is a lever designed to be operated by foot and may refer to:

Computers and other equipment

* Footmouse, a foot-operated computer mouse

* In medical transcription, a pedal is used to control p ...

and Rückpositiv divisions.

Harpsichord builders in the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

built instruments with two keyboard (two manuals) which could be used for transposition. These Flemish instruments served as the model for Baroque-era harpsichord construction in other nations. In France, the double keyboards were adapted to control different choirs (groups) of strings, making a more musically flexible instrument (e.g., the upper manual could be set to a quiet lute stop, while the lower manual could be set to a stop with multiple string choirs, for a louder sound; this enabled the harpsichordist to have two dynamics and tone colours from one instrument). Another approach that could be used on a two manual harpsichord would be to use a coupler to make one manual play two choirs of strings (e.g., an 8' set of strings and a 16' set of strings an octave lower), so that this manual could be used for a loud solo sound, and then having another manual set to trigger only one manual, creating an accompaniment

Accompaniment is the musical part which provides the rhythmic and/or harmonic support for the melody or main themes of a song or instrumental piece. There are many different styles and types of accompaniment in different genres and styles ...

volume. Instruments from the peak of the French tradition, by makers such as the Blanchet family and Pascal Taskin

Pascal-Joseph Taskin (27 July 1723 – 9 February 1793) was a Belgium-born French harpsichord and piano maker.

Biography

Pascal Taskin, born in Theux near Liège, but worked in Paris for most of his life. Upon his arrival in Paris, he apprentice ...

, are among the most widely admired of all harpsichords, and are frequently used as models for the construction of modern instruments. In England, the Kirkman and Shudi firms produced sophisticated harpsichords of great power and sonority. German builders extended the sound repertoire of the instrument by adding sixteen foot choirs, adding to the lower register and two-foot choirs, which added to the upper register.

The piano was invented during the Baroque era by the expert harpsichord maker Bartolomeo Cristofori

Bartolomeo Cristofori di Francesco (; May 4, 1655 – January 27, 1731) was an Italian maker of musical instruments famous for inventing the piano.

Life

The available source materials on Cristofori's life include his birth and death recor ...

(1655–1731) of Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, Italy, who was employed by Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany. Cristofori invented the piano at some point before 1700. While the clavichord allowed expressive control of volume and sustain, it was too quiet for large performances. The harpsichord produced a sufficiently loud sound, but offered little expressive control over each note. The piano offered the best of both, combining loudness with dynamic control.

Cristofori's great success was solving, with no prior example, the fundamental mechanical problem of piano design: the hammer must strike the string, but not remain in contact with it (as a tangent remains in contact with a clavichord string) because this would damp the sound. Moreover, the hammer must return to its rest position without bouncing violently, and it must be possible to repeat the same note rapidly. Cristofori's piano action

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction