Music of Mesopotamia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mesopotamia is a

Mesopotamia is a

The most famous surviving works of music are the Hurrian Hymns, a collection of music inscribed in

The most famous surviving works of music are the Hurrian Hymns, a collection of music inscribed in

Instruments of ancient Mesopotamia include

Instruments of ancient Mesopotamia include

Percussive instruments in ancient Mesopotamia included clappers, scrapers, rattles,

Percussive instruments in ancient Mesopotamia included clappers, scrapers, rattles,

String instruments included

String instruments included

From this relief, Sachs draws three conclusions: (1) that musicians used the

From this relief, Sachs draws three conclusions: (1) that musicians used the

Mesopotamian music had a lasting and widespread influence on the history of music.

Mesopotamian music had a lasting and widespread influence on the history of music.

Music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

was ubiquitous throughout Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n history, playing important roles in both religious and secular contexts. Mesopotamia is of particular interest to scholars because evidence from the region—which includes artifacts, artistic depictions and written records—places it among the earliest well-documented cultures in the history of music. The discovery of a bone wind instrument dating to the 5th millennium BCE provides the earliest evidence of music culture in Mesopotamia; depictions of music and musicians appear in the 4th millennium BCE; and later, in the city of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

, the pictogram

A pictogram, also called a pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto, and in computer usage an icon, is a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and ...

s for ‘harp’ and ‘musician’ are present among the earliest known examples of writing.

Music played a central role in Mesopotamian religion

Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia between circa 6000 BC and 400 AD, after which they largely gave way to Syriac C ...

and some instruments themselves were regarded as minor deities and given proper names, such as the Ninigizibara

Ningizibara, also known as Igizibara and Ningizippara, was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with the ''balaĝ'' instrument, usually assumed to be a type of lyre. She could be regarded both as a physical instrument and as a minor deity. In both ca ...

. Its use in secular occasions included festivals, warfare and funerals—among all classes of society. Mesopotamians sang and played percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

, wind

Wind is the natural movement of air or other gases relative to a planet's surface. Winds occur on a range of scales, from thunderstorm flows lasting tens of minutes, to local breezes generated by heating of land surfaces and lasting a few ...

, and string instrument

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the s ...

s, and instructions for playing them have been discovered on clay tablets. Surviving artifacts include the oldest known string instruments, the Lyres of Ur

The Lyres of Ur or Harps of Ur are a group of four stringed instruments excavated in a fragmentary condition at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in modern Iraq from 1922 onwards. They date back to the Early Dynastic III Period of Mesopotamia, between ...

, which includes the Bull Headed Lyre of Ur.

There are several surviving works of written music; the Hurrian songs, particularly the "Hymn to Nikkal", represent the oldest known substantially complete notated music. Modern scholars have attempted to recreate the melodies from these works, although there is no consensus on exactly how the music would have sounded. The Mesopotamians had an elaborate system of music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (k ...

, and some level of music education

Music education is a field of practice in which educators are trained for careers as elementary or secondary music teachers, school or music conservatory ensemble directors. Music education is also a research area in which scholars do origin ...

. Music in Mesopotamia influenced, and was influenced by, music in neighboring cultures of antiquity based in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

, and the Mediterranean coast

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the eas ...

.

Background

Context

historical region

Historical regions (or historical areas) are geographical regions which at some point in time had a cultural, ethnic, linguistic or political basis, regardless of latterday borders. They are used as delimitations for studying and analysing soc ...

situated between the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

rivers in the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

of modern-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. Considered one of the cradles of civilization

A cradle of civilization is a location and a culture where civilization was created by mankind independent of other civilizations in other locations. The formation of urban settlements (cities) is the primary characteristic of a society that c ...

, it first developed settlements around 10,000 BCE. Northern Mesopotamia included the ancient cities of Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'a ...

, Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a m ...

, Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

and Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ba ...

. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers meet at the Akkad region—later known known as Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

—where several large cities emerged, including Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, Agade

Akkad (; or Agade, Akkadian: , also URI KI in Sumerian during the Ur III period) was the name of a Mesopotamian city. Akkad was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, which was the dominant political force in Mesopotamia during a period of abo ...

, Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

, Ktesiphon, and Seleucia-on-the-Tigris

Seleucia (; grc-gre, Σελεύκεια), also known as or , was a major Mesopotamian city of the Seleucid empire. It stood on the west bank of the Tigris River, within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq.

Name

Seleucia ( grc-gre, ...

. To the south, where the two rivers diverged again, lies the land of Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of ...

. Major cities of Sumer included Ur, Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

, Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

and Lagash

Lagash (cuneiform: LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: ''Lagaš''), was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about east of the modern town of Ash Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba) w ...

. Mesopotamia was rich in clay and fibrous date palms

''Phoenix dactylifera'', commonly known as date or date palm, is a flowering plant species in the palm family, Arecaceae, cultivated for its edible sweet fruit called dates. The species is widely cultivated across northern Africa, the Middle Eas ...

, but lacked other raw materials such as stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

and metal

A metal (from ancient Greek, Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, e ...

, which encouraged trade. The island of Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

in the Persian Gulf was a hub of trading activity connecting Mesopotamia to the ancient cultures of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

.

Two distinct peoples, the Sumerians

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

and the Akkadians

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rul ...

, were the dominant cultures in the region, extending from the earliest examples of writing ( BCE) to the fall of Babylon

The Fall of Babylon denotes the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire after it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BCE.

Nabonidus (Nabû-na'id, 556–539 BCE), son of the Assyrian priestess Adda-Guppi, came to the throne in 556 BCE, afte ...

in 539 BCE. Religion and writing help set the stage for a music culture in this region. The Sumerian and Akkadian pantheons, myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

ologies and rituals intertwined throughout their history. Individual cities had patron deities, who needed to be placated, lest they abandon the city. This was accomplished through lamentation prayers, somber expressions of the grief that would come if the god departed. Music played a central role in this process: hymns

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

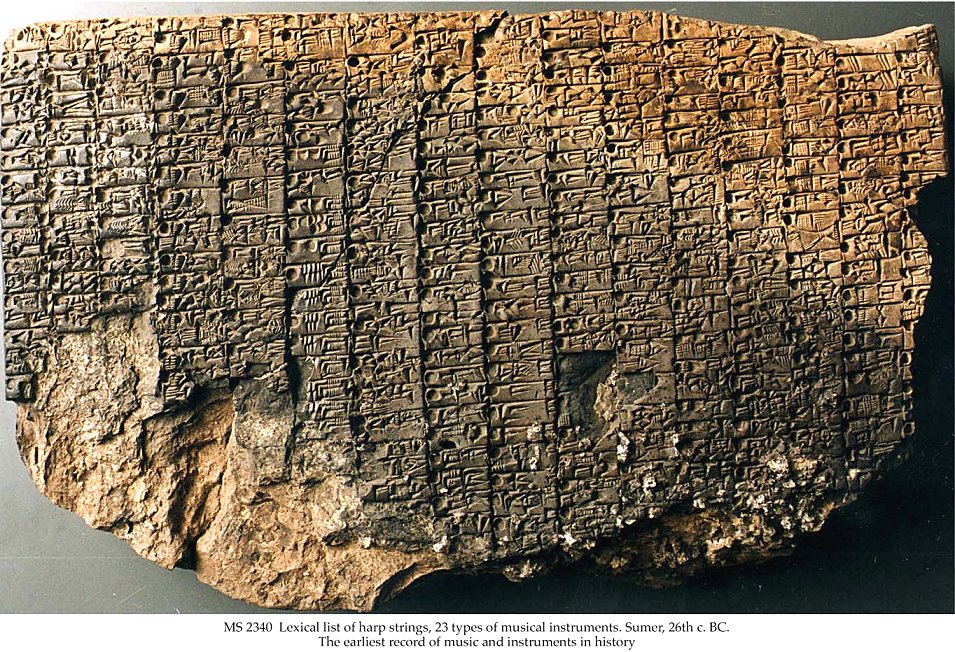

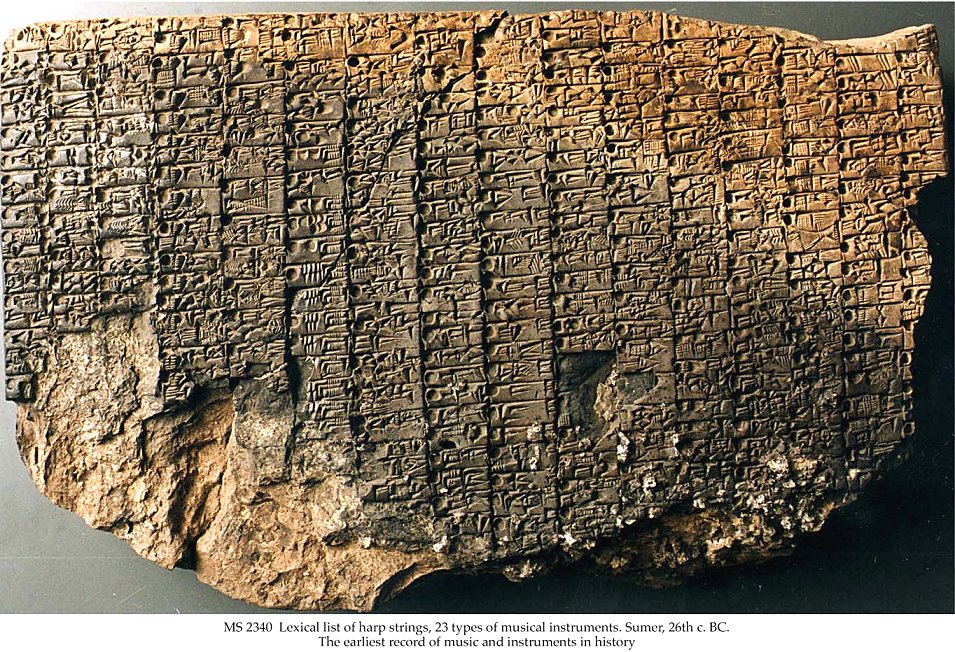

accompanied the ritual singing of these prayers, and some rituals involved an interaction with the instrument itself. Instruments were regarded as intermediaries, minor gods that held sway over major deities. Much of what researchers know about this relationship between Mesopotamian music and religion comes from clay tablets

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylus ...

. Scribes

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promin ...

would use a reed stylus

A stylus (plural styli or styluses) is a writing utensil or a small tool for some other form of marking or shaping, for example, in pottery. It can also be a computer accessory that is used to assist in navigating or providing more precision ...

to make wedge-shaped impressions in wet clay, and the tablets would be baked. While this cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

script would evolve over time, texts about music and musicians are present throughout all stages of the development of writing; they focused on listing instruments, genres, and songs, and articulating their music theory. Piecing together thousands of surviving tablets, researchers have been able to offer a detailed picture of Mesopotamian music culture.

Surviving works

The most famous surviving works of music are the Hurrian Hymns, a collection of music inscribed in

The most famous surviving works of music are the Hurrian Hymns, a collection of music inscribed in cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

on clay tablets excavated from the ancient city of Ugarit

)

, image =Ugarit Corbel.jpg

, image_size=300

, alt =

, caption = Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit

, map_type = Near East#Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size = 300

, relief=yes

, location = Latakia Governorate, Syria

, region = ...

, modern day Syria, dating to approximately 1400 BCE. Hurrian Hymn No. 6, the "Hymn to Nikkal", is considered to be the oldest surviving substantially complete written music in the world. At least five interpretations of this tablet have been made in an attempt to reconstruct the music, notably by Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin, Raoul Vitale, and others. Experts agree on some points, for example, the name of each string of the instrument, its intervals, and its tuning. Nevertheless, each interpretation yields different music. In 2009 Syrian composer Malek Jandali

Malek Jandali ( ar, مالك جندلي, ) (born 1972) is a German-born Syrian-American pianist and composer. He is the founder of the nonprofit organization Pianos for Peace, which aims to build peace through music and education. Jandali immigr ...

released an album, '' Echoes from Ugarit'', which contains an interpretation of Hurrian Hymn No. 6 on piano accompanied by a full orchestra.

The Hurrian hymns were authored by four composers from Ugarit: Tapšihun, Puhiyanna, Urhiya, and Ammiya, and were recorded by two scribes, Ammurabi and Ipšali. Musicologist Richard Dumbrill, who has studied the tablets in detail, reflects on the creation of these works:

Although the music for most hymns is lost, their surviving texts provide insight as to how the compositions were organized. These compositions, according to Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer

Samuel Noah Kramer (September 28, 1897 – November 26, 1990) was one of the world's leading Assyriologists, an expert in Sumerian history and Sumerian language. After high school, he attended Temple University, before Dropsie and Penn, both in ...

, show "a rich variety in both content and structure", and fall into two groups, hymns for the king, and hymns for gods. Kramer details some elements of hymnal organization:

Furthermore, an Akkadian language tablet contains a catalogue of song titles organized by genre, including workmen's songs, shepherds’ songs, love songs, and songs of youth, although the melodies are lost. Nevertheless, Mesopotamian views of love, sex, and marriage can be inferred from some love songs. In two surviving examples, love songs related to a wedding between a priestess and a king “ring out with passionate love and sexual ecstacy”. Kramer infers from the surviving words that some marriages were motivated by sex and love, not just practical considerations, and relates this fact to a Sumerian proverb: “Marry a wife according to your choice!”

Surviving instruments

Although musicians and musical instruments were depicted in Mesopotamian art in various forms over a 3,000 year period, very few instruments have survived. Only eleven stringed instruments have been recovered, nine lyres and two harps, all from theRoyal Cemetery of Ur

The Royal Cemetery at Ur is an archaeological site in modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate in southern Iraq. The initial excavations at Ur took place between 1922 and 1934 under the direction of Leonard Woolley in association with the British Museum and ...

. The most famous are the four Lyres of Ur

The Lyres of Ur or Harps of Ur are a group of four stringed instruments excavated in a fragmentary condition at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in modern Iraq from 1922 onwards. They date back to the Early Dynastic III Period of Mesopotamia, between ...

:

* "Golden Lyre of Ur" (Iraq Museum

The Iraq Museum ( ar, المتحف العراقي) is the national museum of Iraq, located in Baghdad. It is sometimes informally called the National Museum of Iraq, a recent phenomenon influenced by other nations' naming of their national museum ...

)

* "Queen's Lyre" (British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

)

* " Bull Headed Lyre" (Penn Museum

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology—commonly known as the Penn Museum—is an archaeology and anthropology museum at the University of Pennsylvania. It is located on Penn's campus in the University City neigh ...

)

* "Silver Lyre" (British Museum)

The Golden Lyre of Ur now held in the Iraq Museum is a reconstruction; the original was destroyed in the looting that followed the US invasion of Baghdad during the second Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق ( Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict and the War on terror

, image ...

. Musicologist Samuel Dorf details the event:

The destruction of these antiquities during the war sparked widespread international condemnation. In a 2016 event held in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

's Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

meant to condemn ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

and the looting, singer/composer Stef Conner and harpist Mark Hamer performed with a replica of the lyre, recreated by harpist Andy Lowings. The lyre was built of authentic wood, and adorned with lapis lazuli, other precious stones, and $13,000 worth of 24k gold. They played a musical interpretation of ''The Epic of Gilgamesh'' from their 2014 album ''The Flood''.

One of the two harps discovered at Ur is Puabi

Puabi (Akkadian language, Akkadian: 𒅤𒀀𒉿 ''Pu-A-Bi'' "Word of my father"), also called Shubad or Shudi-Ad due to a misinterpretation by Sir Charles Leonard Woolley, was an important woman in the Sumerian city of Ur, during the First Dyn ...

's harp, an especially ornate harp found in the grave of Queen Puabi. Whereas the largest of the lyres had a register similar to a modern bass viol, and the smaller silver lyre had a register like a cello, Puabi's harp fell in the register of a small guitar. UC Berkeley professor Robert R. Brown made three playable replica's of Puabi's harp, one of which is held in the British Museum. Claire Polin describes the richly adorned instrument:

Other instruments discovered at the cemetery include a pair of silver pipes, as well as drums, sistra, and cymbals. In earlier findings dating to the 5th millennium BCE, two bone wind instruments have been recovered, one complete and the other in fragments. Also recovered is a fragment of a clay whistle from Uruk dating to c. 3200 BCE. Two pairs of copper clappers from Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

are in the Oriental Institute, and there are two scraper instruments dating to 1500 BCE in the Teheran Archaeological Museum. There is a large, elaborately decorated Assyrian bell in the Berlin Museum. At one time there was a bone whistle recovered from Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a m ...

, which produced three distinct pitches, but it has been lost.

Overview

Uses of music

Religious

Music played a central role in ancient Mesopotamian religion. In theOld Babylonian

Old Babylonian may refer to:

*the period of the First Babylonian dynasty (20th to 16th centuries BC)

*the historical stage of the Akkadian language

Akkadian (, Akkadian: )John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, "Akkadian and Eblaite", ''The Camb ...

period, when music was performed as part of a religious ceremony, the practitioners, known as Gala priests, sang in a dialect of Sumerian called Emesal

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 3000 BC. It is accepted to be a local language isolate and to have been spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day ...

. There were two types of Emesal prayers, the Balag

In Mesopotamia, a balag (or balaĝ) refers both to a Sumerian religious literary genre and also to a closely associated musical instrument. In Mesopotamian religion, Balag prayers were sung by a Gala priest as ritual acts were performed around ...

and the Ershemma, named after the instruments used in their performance (the Balag and Shem, respectively). Other musical instruments associated with the Gala priests include the ''ub'' (small drum), ''lilis'' (timpani), and ''meze'' (sistrum or cymbals), although not much is known about these instruments.

Evidence from the city of Mari offers a picture of how the musicians were situated within the temple. An instrument called the Ninigizibara

Ningizibara, also known as Igizibara and Ningizippara, was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with the ''balaĝ'' instrument, usually assumed to be a type of lyre. She could be regarded both as a physical instrument and as a minor deity. In both ca ...

was placed opposite a statue of that city's deity, Eštar. Singers sat to the right of the instrument, an orchestra sat to its left, and female musicians stood behind the instrument. Ritual acts were performed during these sung lamentation

A lament or lamentation is a passionate expression of grief, often in music, poetry, or song form. The grief is most often born of regret, or mourning. Laments can also be expressed in a verbal manner in which participants lament about somethin ...

prayers, whose purpose was to persuade the local deity not to abandon the city. Moreover, some laments included grief over the loss of music itself during the destruction of a city and its temple. In one such work, the "weeping goddess" Ninisinna laments the destruction of her city, Isin

Isin (, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. Excavations have shown that it was an important city-state in the past.

History of archaeological research

Ishan al-Bahriyat was visited ...

, not only bemoaning the loss of food, drink, and luxury, but also because there was “no sweet-sounding musical instruments such as the lyre, drum, tambourine, and reed pipe; no comforting songs and soothing words from the temple singers and priests.”

Some rituals involved the instruments themselves, deified, and capable of receiving animal sacrifices as gods. In a ritual closely associated with a drum described in an Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

text, a bull was brought to the temple and offerings were made to Ea, god of music and wisdom. The bull was then singed. Twelve linens were placed on the ground, and a bronze image of a god was placed on top of each linen. Sacrifices were made and a drum was put into place. The bronze images were then put inside the drum, incantations were whispered into the bull's ears, a hymn was sung accompanied by an oboe, and the bull was sacrificed.

Secular

The Akkadian word for music, ''nigūtu'', also meant ‘joy’ and ‘merriment’, well illustrated by a seal in theLouvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the '' Venus de Milo''. A central ...

showing a peaceful scene of a shepherd playing a flute to his flock. Music was a normal part of social life in Mesopotamia and was used in many secular contexts, such as at banquets, among royalty, and at festivals, where musicians were often accompanied by dancers, jugglers, and acrobats. Music played important roles at funerals and in the military, and was also depicted in relation to sports and sex. Mesopotamian love songs, which represented a distinct genre of music, nevertheless shared features in common with religious music. Inana and Dumuzi, often featured in laments, are also prominent as the divine lovers in romantic songs, and they both use Emesal, a dialect associated with women. The use of Emesal by women singers extended into wedding songs as well, but over time these singing roles were taken over by male performers, at least among the elite.

Musicologist J. Peter Burkholder

J. Peter Burkholder (born June 17, 1954) is an American musicologist and author. He is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. He has written numerous monographs, essays, and journal artic ...

lists genres of secular music including "work songs, nursery songs, dance music, tavern music, music for entertaining at feasts, and epics sung with instrumental accompaniment." Vibrant wall paintings illustrate dancing

Dance is a performing art form consisting of sequences of movement, either improvised or purposefully selected. This movement has aesthetic and often symbolic value. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoi ...

, and several genres of dance can be distinguished on wall reliefs, cylinder seals, and painted pottery, and depictions of musical instruments accompany them. Secular music was comforting to the Mesopotamian people; one incantation tells of a homesick scribe who was stuck and ill in Elam-Anían; he longed “to be healed by the music of the horizontal harp with seven strings.”

Music education

Professional musicians would be trained as apprentices, being eligible for employment in numerous settings. Sumerian texts indicate that choral training occurred by 3000 BCE in the temple of Ningarsu inLagash

Lagash (cuneiform: LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: ''Lagaš''), was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about east of the modern town of Ash Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba) w ...

, which developed into highly complex responsorial chanting with instrumental parts, which the musicologist Charles Plummeridge notes "must have required expert tuition and direction." Some religious practices were highly specific in teaching music. Instructions on surviving clay tablets include information on how to play musical instruments. It is debated whether these texts applied to a mainstream musical tradition or a smaller and more theoretical discipline.

With ancient Egypt, Mesopotamian society included the earliest known schools to teach music. Active by the 3rd millennium BCE, these schools—known as eduba

Edubba ( sux, ) is the Sumerian for "scribal school." The eduba was the institution that trained and educated young scribes in ancient Mesopotamia during the late third or early second millennium BCE. Most of the information known about edub ...

s—were chiefly for educating scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

s and priests. Extant clay tablets often record information on student activities in edubas, and indicate that their examinations included questions on differentiating and identifying instruments, singing technique, and analyzing

Analysis (plural, : analyses) is the process of breaking a complexity, complex topic or Substance theory, substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics a ...

compositions. Knowledge of music was essential in these roles, as the students would later become important cultural and religious figures. Outside of edubbas, the children of the elite received a comprehensive education in reading, writing, religion, the sciences, law and medicine, among other topics; whether music was included is largely uncertain. A nascent music school existed in Mari, where young musicians may have been purposefully blinded for unknown reasons. Some evidence suggests that Mesopotamians had toy

A toy or plaything is an object that is used primarily to provide entertainment. Simple examples include toy blocks, board games, and dolls. Toys are often designed for use by children, although many are designed specifically for adults and pet ...

instruments.

Musicians

Societal role

Sumerian and Akkadian language texts provide insight into the role of musicians in society. Two distinct types of musicians are known, the ''gala'' and the ''nar''. Both classes of musician were regarded highly, and associated with religion and royalty, but their roles differed. The ''gala'' (Akkadian ''kalû'') musician was closely associated with temple rituals, and their job may have been considered less glamorous and temporary. There are hundreds of individual named musicians, such as the Gala musician Ur-Utu, who are known from administrative documents. In some cases, archaeological findings have identified the homes and family histories of these musicians, revealing their high status in society. Gala musicians were associated with the godEnki

, image = Enki(Ea).jpg

, caption = Detail of Enki from the Adda Seal, an ancient Akkadian cylinder seal dating to circa 2300 BC

, deity_of = God of creation, intelligence, crafts, water, seawater, lakewater, fertility, semen, magic, mischief

...

.

The ''nar'' (Akkadian ''nāru'') musician, who had a close association with royalty, was known to play and transport musical instruments and to have close correspondence with the king. The chief musician of the palace directed musical performances and also taught apprentice musicians. In the royal harem, where the king kept wives, concubines, children, and servants, the king also kept young apprentice musicians. The possession of musicians was a sign of status, and musicians were traded over long distances, including as diplomatic gifts and in war. When the Assyrian military conquered a city, they spared the musicians and sent them to Nineveh with the spoils. An epic tale called “The Death of Gilgamesh” details how Gilgamesh offered gifts to the gods on behalf of his wives and children, but also on behalf of his musicians. Musicians, alongside the royal family, sometimes accompanied the king to his grave.

The gender of ancient Mesopotamian musicians is debated. Some sources indicate that Gala priests, for example, were either genderfluid

Non-binary and genderqueer are umbrella terms for gender identities that are not solely male or femaleidentities that are outside the gender binary. Non-binary identities fall under the transgender umbrella, since non-binary people typically ...

or regarded as a third gender. Gabbay writes, "The term Gala/kalû should be understood as a general concept, relating to a third gender which shares features of both female and male, but which is an independent gender category." Other sources suggest they may have been homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

or intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical b ...

. Still other texts, including music instruction texts, differentiate between male and female apprentice musicians. Some of the ambiguity surrounding the gala's gender could be explained by the history of lamentation prayers, which may have originated with the funerary laments of women. The earliest documented gala performance was in the context of a funeral, with women lamenters accompanying the gala in the mourning. These origins may explain why female characteristics, and the dialect associated with women, Emesal, have long been associated with the gala and temple prayers.

Specific personalities

Shulgi

Shulgi ( dŠulgi, formerly read as Dungi) of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC (Middle Chronology) or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC (Short Chronology). His accomplishme ...

of Ur, who ruled c. 2094 – c. 2046 BCE during the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

, was a generous patron of the arts, especially music. In self-laudatory texts, he professed to be an expert musician, claiming that it came easy to him. He listed numerous instruments he claimed to have mastered: the ''algar'', the ''sabitum'', the ''miritum'', the ''urzababitum'', the ''harhar'', the “Great Lion,” the ''dim'', and the ''magur''; he also claimed to have mastered the art of composition of genres such as the ''tigi'' and the ''adab''. Shulgi seemed to enjoy playing all instruments except the reed pipe, which he believed brought sadness to the spirit, whereas music should bring joy and cheer. Shulgi generously funded Sumer's two major edubbas, those of Ur and Nippur; in return, Sumerian poets composed hymns of glorification in his honor.

The best known musician of the Ur III period, Dada, was a wealthy individual who held the title of gala (or gala-mah). His career began during the reign of Shulgi, and it seems that he was a special kind of gala who acted as the gala of the royal court or even of the state, and was in charge of other galas. Dada organized musical events, looking after both the instruments and related entertainment, including handling a bear cub. He and his family owned residences in both Girsu and Ur, and two of Dada's children, Hedut-Amar-Sin and Šu-Sin-migir-Eštar, entertained the king with their own music. Dada's main assistant, or perhaps star performer, was a nar musician named Ur-Ningublaga. While Dada's story offers a glimpse into the life of a Mesopotamian musician, it is likely that he was an exceptional example, and that most gala musicians would have held more mundane roles.

Among the earliest known composers in the history of music was an Akkadian priestess, Enheduanna

Enheduanna ( sux, , also transliterated as , , or variants) was the priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in the Sumerian city-state of Ur in the reign of her father, Sargon of Akkad. She was likely appointed by her father as the leader of t ...

, active around 2300 BCE. The daughter of Sargon of Akkad

Sargon of Akkad (; akk, ''Šarrugi''), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.The date of the reign of Sargon is highl ...

, founder of the Akkadian Empire, Enheduanna was simultaneously a princess, priestess, and poetess who wrote a cycle of hymns to the temples of Sumer and Akkad, including devotional hymns for the gods Sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

and Inanna

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

, the texts for which survive. Her work was prolific and also well documented; as many as fifty copies of some of her works have survived. She authored ''nin-me-sar-ra'', and is the likely author of a hymn entitled the ‘Myth of Inanna and Ebih’ (''in-nin me-huš-a''). Some of her works had themes related to her father's accomplishments, while others are autobiographical—she speaks in the first person at least once. Her poems were quite popular in Babylon and her hymnal organization likely influenced many generations of composers. She is referred to by name in a hymn to Dumuzi, attesting to her popularity in the region.

Instruments

Instruments of ancient Mesopotamia include

Instruments of ancient Mesopotamia include harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orc ...

s, lyre

The lyre () is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it ...

s, lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

s, reed pipe

A reed pipe (also referred to as a ''lingual'' pipe) is an organ pipe that is sounded by a vibrating brass strip known as a ''reed''. Air under pressure (referred to as ''wind'') is directed towards the reed, which vibrates at a specific pitc ...

s, and drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

s. While much is known about Mesopotamian instruments, musicologist Carl Engel points out that because the main depictions of musical instruments come from bas reliefs celebrating royal and religious events, it is likely that there are many instruments, perhaps popular ones, that scholars are unaware of.

Divination of instruments

Musical instruments were intimately associated with Mesopotamian religion, and some were regarded as minor gods - intermediaries that could help the priest communicate with a major god. Clear evidence for the divination of musical instruments comes from the Sumerian language. The use ofdeterminative

A determinative, also known as a taxogram or semagram, is an ideogram used to mark semantic categories of words in logographic scripts which helps to disambiguate interpretation. They have no direct counterpart in spoken language, though they may ...

s, or unvocalized logograms that show the category of a noun, inform the reader whether the object in question is, for example, made of wood (, giš

The cuneiform giš sign, (also common for is, iṣ, and iz), is a common, multi-use sign, in the '' Epic of Gilgamesh'', the Amarna letters, and other cuneiform texts. It also has a major usage as a sumerogram, GIŠ, (capital letter (majuscul ...

), is a person (, lú), or is a building (, é); the proper names of certain Mesopotamian musical instruments are always accompanied by the divine determinative (, dingir

''Dingir'' (, usually transliterated DIĜIR, ) is a Sumerian word for " god" or "goddess". Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is ...

) used for gods. Furthermore, these instruments’ names appear in written lists of gods. Franklin writes, "These were not ''symbols'' of the gods, but ''instantiations'' of some sort ��divinized cult-objects ''were'' gods." The instruments were the intended recipients of various offerings, such as animal sacrifice, spices, or jewelry.

This was especially true of an instrument known as a balag

In Mesopotamia, a balag (or balaĝ) refers both to a Sumerian religious literary genre and also to a closely associated musical instrument. In Mesopotamian religion, Balag prayers were sung by a Gala priest as ritual acts were performed around ...

, whose identity is disputed but which may have been a string instrument or a drum. Examples of known instrument-gods include balags such as the ‘Red-Eyed Lord’ (''Lugal-igi-ḫuš''). Gudea

Gudea ( Sumerian: , ''Gu3-de2-a'') was a ruler ('' ensi'') of the state of Lagash in Southern Mesopotamia, who ruled circa 2080–2060 BC (short chronology) or 2144-2124 BC ( middle chronology). He probably did not come from the city, but had mar ...

commissioned balags, including 'Great Dragon of the Land' (''Ušumgal-kalama'') and 'Lady as Exalted as Heaven'. Several balags are known to have been minor gods to the sun-god Utu, associated with law and justice, including ‘Let me live by His Word’, ‘Just Judge’, and ‘Decision of Sky and Earth’. Another named instrument-god is ''Nin-an-da-gal-ki''. During Gudea's reign in Lagash (c. 2100 BCE), some calendar years were named for the balag that was deified and dedicated. Furthermore, some kings inserted their names into the proper name of the instrument; Ishbi-Erra

Ishbi-Erra (Akkadian: d''iš-bi-ir₃-ra'') was the founder of the dynasty of Isin, reigning from ''c.'' 2017 — ''c.'' 1986 BC on the middle chronology or 1953 BC — ''c.'' 1920 BC on the short chronology. Ishbi-Erra was preceded by Ibbi-Si ...

, during the Isin dynasty

The Dynasty of Isin refers to the final ruling dynasty listed on the ''Sumerian King List'' (''SKL''). The list of the Kings Isin with the length of their reigns, also appears on a cuneiform document listing the kings of Ur and Isin, the ''List of ...

, dedicated a deified balag named 'Ishbi-Erra trusts in Enlil', suggesting that each instrument was “an intermediary between the earthly king and his divine counterpart.” During the rituals associated with this instrument, the lines between priest, musician, instrument, god, and king were blurred, and within this context the Mesopotamians believed the balag played itself.

Voice

Contracts for the employment of musicians in temples survive, and reveal that a large number of singers were used in the ritual performances. While the exact nature of these performances will never be known,musicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some m ...

Peter van der Merwe speculates that the vocal tone or timbre was probably similar to the "pungently nasal sound" of the narrow-bore reed pipes. He suggests that ancient Mesopotamian singing shared characteristics with contemporary vocal quality and techniques, including dynamic changes and graces

In Greek mythology, the Charites ( ), singular ''Charis'', or Graces, were three or more goddesses of charm, beauty, nature, human creativity, goodwill, and fertility. Hesiod names three – Aglaea ("Shining"), Euphrosyne ("Joy"), and Thali ...

, shakes, mordent

In music, a mordent is an ornament indicating that the note is to be played with ''a single'' rapid alternation with the note above or below. Like trills, they can be chromatically modified by a small flat, sharp or natural accidental. The t ...

s, glides and microtonal inflections associated with a nasal timbre. Reliefs carved in stone show that singers would sometimes squeeze their larynx with their fingers in order to achieve high notes. Researchers also know that choral singing was sometimes done in unison and at other times in parts; Geshtinanna

Geshtinanna was a Mesopotamian goddess best known due to her role in myths about the death of Dumuzi, her brother. It is not certain what functions did she fulfill in the Mesopotamian pantheon, though her association with the scribal arts and dr ...

was the muse of signing in unison.

Percussion

Percussive instruments in ancient Mesopotamia included clappers, scrapers, rattles,

Percussive instruments in ancient Mesopotamia included clappers, scrapers, rattles, sistra

A sistrum (plural: sistra or Latin sistra; from the Greek ''seistron'' of the same meaning; literally "that which is being shaken", from ''seiein'', "to shake") is a musical instrument of the percussion family, chiefly associated with ancient ...

, cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s, bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inte ...

s and drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

s. A scraper consisted of a stick and an object with notches cut in it, while rattles were made of gourds or other materials and contained pebbles or clay objects to produce the rattling sound when shook. A Mesopotamian sistrum consisted of a handle, a frame, and cross bars that jingled. Cymbals were small and massive, with some shaped like plates and others like cups, and some were made of bronze.

Mesopotamian art depicts at least 4 types of drums: a shallow drum, which a Sumerian relief dating to 2100 BCE depicts as an estimated 1.7 meters across, and which required two men to play; a small cylindrical drum held horizontally; a large footed drum; and a small drum with one head, carried vertically. Sumerian drums were made of metal rather than wood and were played with the hands rather than sticks. The skin of the Babylonian drum was made from bull hide, and the placement of the skin over the sacred instrument was itself the subject of a ritual at the Temple of Ea.

Wind

Almost no wind instruments survive, but there is ample evidence of their use in artistic depictions and literature. Wind instruments includedflutes

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

, oboes

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

, horns, and pan-pipes

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

, made of wood, animal horn, bone, metal, and reed. A short horn instrument used by the Hittites was a precursor to the Jewish shofar

A shofar ( ; from he, שׁוֹפָר, ) is an ancient musical horn typically made of a ram's horn, used for Jewish religious purposes. Like the modern bugle, the shofar lacks pitch-altering devices, with all pitch control done by varying ...

. The reed pipe was an instrument played on sad occasions, such as funerals.

Two silver pipes dating to 2800 BCE were discovered in Ur. Both pipes are 24 cm in length. One has four finger holes and the other has three; when placed next to each other, three of the finger holes from each pipe are aligned. While scholars agree this was a reeded instrument, it's unclear whether it was a single or double reed

A double reed is a type of reed used to produce sound in various wind instruments. In contrast with a single reed instrument, where the instrument is played by channeling air against one piece of cane which vibrates against the mouthpiece an ...

, although some scholars claim that ancient Mesopotamians did not have a single-reeded instrument such as a clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitch ...

. The silver pipes represent the oldest known wind instrument, predating a set of Egyptian reed pipes by 500 years. Similar pipes made of gold, silver, and bronze are described in texts from the same city.

The word “flute” appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with ...

, the earliest surviving literary work from Mesopotamia. The text describes “A flute of carnelian” (Tablet VIII, line 148, translation by Andrew R. George

Andrew R. George (born 1955) is a British Assyriologist and academic best known for his edition and translation of the '' Epic of Gilgamesh''. Andrew George is Professor of Babylonian, Department of the Languages and Cultures of Near and Middle ...

). There are numerous depictions of flutes in visual art throughout Mesopotamian history, including a woman playing a flute on a Sumerian shell ornament from Nippur

Nippur ( Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. Akkadian: ''Nibbur'') was an ancient Sumerian city. It was ...

dating to 2600-2500 BCE, a flutist on an Akkadian cylinder seal dating to 2400-2200 BCE, an ivory box from Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a m ...

dating to 900-700 BCE, and in a bas-relief from Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ba ...

dating to 645 BCE.

String

String instruments included

String instruments included harps

The High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) is a high-precision echelle planet-finding spectrograph installed in 2002 on the ESO's 3.6m telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile. The first light was achieved in February 2003. ...

, lyres, lutes

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can refer ...

, and psalteries. The Mesopotamian harp originated from the warrior's bow, perhaps by the addition of a gourd as a resonator, and through accident and experimentation became the ancestor to the lyre and other stringed instruments. Strings may have been made with catgut, as was done by the Egyptians, or with silk. Plucked instruments came in many varieties, differing in the manner in which they were intended to be held. When used by royalty or as part of a religious ceremony, they were adorned with precious metals and stones, such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and mother of pearl.

The body of the lyre was a representation of an animal's body, such as a cow, bull, calf, donkey, or stag. Archaeologist Leonard Woolley

Sir Charles Leonard Woolley (17 April 1880 – 20 February 1960) was a British archaeologist best known for his excavations at Ur in Mesopotamia. He is recognized as one of the first "modern" archaeologists who excavated in a methodical way, ...

suggested that the animal head depicted on the front of the lyre indicated the instrument's register. For example, a bull-headed lyre is in the bass register, a cow-headed lyre is a tenor, and a calf-headed lyre is an alto. The legs of the instrument were meant to represent animal legs, with the rear post as the tail. The instrument was played either in place with its legs on the ground, or as part of a procession, carried over the shoulder with a strap.

The lute may have originated in Mesopotamia, or it may have been introduced from surrounding regions, such as by the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

, Hurrians

The Hurrians (; cuneiform: ; transliteration: ''Ḫu-ur-ri''; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri or Hurriter) were a people of the Bronze Age Near East. They spoke a Hurrian language and lived in Anatolia, Syria and Northern Me ...

or Kassites

The Kassites () were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC (short chronology).

They gained control of Babylonia after the Hittite sack of Babylo ...

, or from the west by nomadic people of the semidesert plains of Syria. The oldest pictorial record of lute playing is on an Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

-period cylinder seal

A cylinder seal is a small round cylinder, typically about one inch (2 to 3 cm) in length, engraved with written characters or figurative scenes or both, used in ancient times to roll an impression onto a two-dimensional surface, generally ...

(British Museum) dating to 3100 BCE that depicts a female figure with a long-necked instrument sitting at the back of boat in a musician's posture. Later representations appear after the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

, including a relief from Larsa (Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the '' Venus de Milo''. A central ...

) showing a sexual scene involving two participants, a lute, and a small drum; a relief from Mari (Iraq Museum) depicting bow-legged figures playing three-stringed lutes while apes watch; a relief from Nippur ( Philadelphia Museum) showing a shepherd playing a lute; a relief from Nippur (Iraq Museum) showing a figure holding a lute in the right hand and a plectrum in the left; a relief from Uruk (Vorderasiatisches Museum

The Vorderasiatisches Museum (, ''Near East Museum'') is an archaeological museum in Berlin. It is in the basement of the south wing of the Pergamon Museum and has one of the world's largest collections of Southwest Asian art. 14 halls distri ...

) showing a lute being played alongside a lyre; and a Kassite seal (Louvre) showing the same. Lutes were modified and adapted as they influenced neighboring regions.

Two surviving tablets give instructions for tuning string instruments. According to Sam Mirelman, these tablets are better thought of in terms of re-tuning rather than tuning:

David Wulstan offers an excerpt from a small fragment of such a text:

By piecing together such fragments, researchers have been able to come up with what Leon Crickmore called "credible reconstructions" of the Mesopotamian tuning systems for string instruments. A text composed by Shulgi

Shulgi ( dŠulgi, formerly read as Dungi) of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC (Middle Chronology) or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC (Short Chronology). His accomplishme ...

around 2070 BCE articulates technical terms such as ‘tuning up’ (ZI.ZI), ‘tuning down’ (ŠÚ.ŠÚ), ‘tightening’ (GÍD.I), ‘loosening’ (TU.LU), and the term ‘adjust the frets’ (SI.AK). Clay tablets also reveal the names of the nine strings: '1st', '2nd', '3rd-thin', 'God-Ea-made-it', '5th', '4th-behind', '3rd-behind', '2nd-behind', '1st-behind'.

Music theory

A corpus of thousands of surviving clay tablets provide additional details about ancient Mesopotamian music theory. While some relate to tuning, others relate to musical scales. An Akkadian language mathematical text contains references to musical strings, and a tablet from Ugarit lists musical interval names along with two numbers, presumably referring to the two strings plucked. Mesopotamian art also provides information; the musicologistCurt Sachs

Curt Sachs (; 29 June 1881 – 5 February 1959) was a German musicologist. He was one of the founders of modern organology (the study of musical instruments). Among his contributions was the Hornbostel–Sachs system, which he created with Er ...

describes a relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

that depicts the Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

ite court orchestra as it welcomes the Assyrian conqueror in 650 BCE:

pentatonic scale

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale with five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed independently by many an ...

, (2) that different orchestra members played different parts, and (3) that musicians knew how to use chords

Chord may refer to:

* Chord (music), an aggregate of musical pitches sounded simultaneously

** Guitar chord a chord played on a guitar, which has a particular tuning

* Chord (geometry), a line segment joining two points on a curve

* Chord ( ...

. Researchers also know that the Mesopotamians used a heptatonic

A heptatonic scale is a musical scale that has seven pitches, or tones, per octave. Examples include the major scale or minor scale; e.g., in C major: C D E F G A B C—and in the relative minor, A minor, natural minor: A B C D E F G A; the m ...

, diatonic, Lydian scale. They had the concept of musical intervals, including the octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

, understood the circle of fifths

In music theory, the circle of fifths is a way of organizing the 12 chromatic pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths. (This is strictly true in the standard 12-tone equal temperament system — using a different system requires one interval of ...

, and a Babylonian tablet reveals the Mesopotamians also used another visualization of the heptatonic tuning system represented as a seven-pointed star. The ancient Mesopotamians used a cyclic theory of music; on a nine-stringed harp, the strings were numbered from one to five, then back down to one.

Tablets reveal that string instruments were tuned by alternating descending fourths and ascending fifths; this tuning procedure would later be called Pythagorean, although the Babylonians had worked out the heptatonic system many centuries before Greece. The seven heptatonic scales (and their Greek equivalents) were: išartu (Dorian), kitmu (Hypodorian), embūbu (Phrygian), pūtu (Hypophrygian), nīd qabli (Lydian), nīš gabarî (Hypolydian), qablītu (Mixolydian). The Babylonians regarded the tritone as dissonant and called it ‘impure’. Duchesne-Guillemin lists the four rules that governed the tuning of these instruments:

Influence

Mesopotamian music had a lasting and widespread influence on the history of music.

Mesopotamian music had a lasting and widespread influence on the history of music. Trade routes

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

allowed for the free flow of musical instruments, while classical education spread Mesopotamian musical theory and insights. From 1300 BCE onwards, musician-priests formed guilds and were housed in a temple college, attracting intellectual attention from across the region. Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

, home to an independent culture of its own, had connections with both the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900& ...

to the southeast, and also with Mesopotamia to the north. For much of ancient history

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

, Egypt, Israel, Phoenicia, Syria, Babylonia, Asia Minor, Italy, and Greece together formed what musicologist Claire Polin

Claire Polin (January 1, 1926 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – December 6, 1995 in Merion, Pennsylvania) was an American composer of contemporary classical music, musicologist, and flutist.

Education

She obtained degrees in music (including a do ...

called a "musical province in which free intercourse created understanding in musical exchange". Musicologist Peter van der Merwe writes:

The spread of some instruments can be traced. The lute, or ''sinnitu'', appeared in Mesopotamia about the same time as similar instrument in Egypt, the ''nefer''. This instrument became well known throughout the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

as the ''tambour

In classical architecture, a tambour ( Fr.: "drum") is the inverted bell of the Corinthian capital around which are carved acanthus leaves for decoration.

The term also applies to the wall of a circular structure, whether on the ground or rais ...

'', and has parallels to the Sumerian ''pan-tur'', the Greek ''pandoura'', the Russian ''balalaika'', the Georgian ''tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bi ...

'', and the Indian '' vînâ''. The Hebrew flute (''halil'') is derived from the Akkadian ''hal-hallatu''. The New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth century BC and the eleventh century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties of Egypt. Radioca ...

borrowed Mesopotamian instruments such as an angular vertical harp and a square drum. A seal from Ur dated to 2,800 BCE depicts a small animal playing a pair of clappers; similar clappers appear in ancient Egypt centuries later. Contemporary East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

n lyres and West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

n lutes preserve many features of Mesopotamian instruments. Mesopotamian harps diffused as far west as the Mediterranean and as far east as Asia. Mesopotamian influence in Syria can be seen in the ''abbūba'', ''tablā'', ''pelāggā'', ''qarnā'', and ''zemmōra'' instruments.

Classical education also helped disseminate musical ideas. The Mesopotamian musical system made up part of the classical education curriculum that scribes, priests and other educated professionals went through, and there were major Mesopotamian music centers at the temples of Babylon, Sippar, Nippur, and Erech. These musical centers became famous in the western world and attracted the attention of the Greeks, including Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

, for their musical achievements in addition to those in mathematics and astronomy. This classical education spread abroad during the second millennium BCE, and these musical systems came to represent a common language from which cities abroad could adapt to their local circumstances in syncretism.

For example, pottery in the Mediterranean and Near East showed a common, stereotyped motif — a typical musical ensemble that could be found throughout the region, consisting of lyres, double pipes, and percussion. Variations in this motif show local adaption, for example in ancient Greece the asymmetrical West Semitic lyres are replaced with Hellenistic instruments. Musical terms also appear in connection with religious practices. The Sumerian logogram for ‘gala’ (kalû in Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

) appeared in Hatti Hatti may refer to

*Hatti (; Assyrian ) in Bronze Age Anatolia:

**the area of Hattusa, roughly delimited by the Halys bend

**the Hattians of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC

**the Hittites of ''ca'' 1400–1200 BC

**the areas to the west of the Euphr ...

, where the word also designated a musician-priest—a type of drummer—and was pronounced as in Hittite as šahtarili. While the gala and šahtarili were both musicians and priests, they were not identical. The Sumerian gala priests were often associated with a third gender category, whereas the šahtarili were typically men; furthermore, there was no Hatti counterpart to Ištar - the two types of priests were involved in the worship of two distinct pantheons.

Greece

Mesopotamian music had a strong influence in ancient Greece. The practice of deifying stringed instruments originated in Mesopotamia during the late third millennium BCE, and spread abroad over the next thousand years. In this belief system, the relationship between music and the divine is so strong that an instrument itself could receive asacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

, as a god. This practice is echoed in Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Marti ...

, and also predates the Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

doctrine of the Harmony of the Spheres

The ''musica universalis'' (literally universal music), also called music of the spheres or harmony of the spheres, is a philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies – the Sun, Moon, and planets – as a fo ...

, in which the tuning of the lyre was seen as “a microcosm of a universal harmony.” The Greeks inherited their numerology-mysticism from the Mesopotamians, and this included seven-note scales and the Greek fascination with the number seven, especially in supernatural contexts, including in the mythology surrounding the Oracle at Delphi

Pythia (; grc, Πυθία ) was the name of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as the Pythoness ...

. Morever, the Greeks inherited the Mesopotamians’ emphasis on the 7-stringed lyre, a 7-pitched scale, and in compositions that focus on the central string, such as the Hurrian hymns. Greek music, in turn, had a strong influence on Roman music, especially after the Roman conquest of the Greek mainland in 168 BCE; the musical theory inherited by the Romans led to the eight principal modes of Gregorian chant. The modern Western seven-note scales are nearly identical to those used by the Mesopotamians and then the Greeks.

Persia

Four thousand years ago inancient Iran

The history of Iran is intertwined with the history of a larger region known as Greater Iran, comprising the area from Anatolia in the west to the borders of Ancient India and the Syr Darya in the east, and from the Caucasus and the Eurasian Step ...