Multiple barrel firearm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A multiple-barrel firearm is any type of

A multiple-barrel firearm is any type of

Multiple-barrel firearms date back to the 14th century, when the first primitive volley guns were developed. They are made with several single-shot

Multiple-barrel firearms date back to the 14th century, when the first primitive volley guns were developed. They are made with several single-shot

A pepper-box gun or "pepperbox revolver" has three or more barrels revolving around a central axis, and gets the name from its resemblance to the household pepper shakers. It has existed in all ammunition systems:

A pepper-box gun or "pepperbox revolver" has three or more barrels revolving around a central axis, and gets the name from its resemblance to the household pepper shakers. It has existed in all ammunition systems:

The original

The original

By 1790, Joseph Manton, acknowledged as the “father of the modern shotgun”, first brought together all the facets of the contemporary

By 1790, Joseph Manton, acknowledged as the “father of the modern shotgun”, first brought together all the facets of the contemporary

The Gatling gun is one of the best-known early rapid-fire weapons and a forerunner of the modern

The Gatling gun is one of the best-known early rapid-fire weapons and a forerunner of the modern

A multiple-barrel firearm is any type of

A multiple-barrel firearm is any type of firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

with more than one gun barrel

A gun barrel is a crucial part of gun-type weapons such as small firearms, artillery pieces, and air guns. It is the straight shooting tube, usually made of rigid high-strength metal, through which a contained rapid expansion of high-pres ...

, usually to increase the rate of fire

Rate of fire is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire or launch its projectiles. This can be influenced by several factors, including operator training level, mechanical limitations, ammunition availability, and weapon condition. In m ...

or hit probability and to reduce barrel erosion/overheating.

History

Volley gun

Multiple-barrel firearms date back to the 14th century, when the first primitive volley guns were developed. They are made with several single-shot

Multiple-barrel firearms date back to the 14th century, when the first primitive volley guns were developed. They are made with several single-shot barrels

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids, u ...

assembled together for firing a large number of shots, either simultaneously or in quick succession. These firearms were limited in firepower by the number of barrels bundled, and needed to be manually prepared, ignited and reloaded for each firing.

In practice the large volley guns were not particularly more useful than a cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

firing canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel artillery ammunition. Canister shot has been used since the advent of gunpowder-firing artillery in Western armies. However, canister shot saw particularly frequent use on land and at sea in the various ...

or grapeshot. Since they were still mounted on a carriage, they could be as hard to aim and move around as a heavy cannon, and the many barrels took as long (if not longer) to reload.Matthew Sharpe "Nock's Volley Gun: A Fearful Discharge" ''American Rifleman'' December 2012 pp.50-53 They also tended to be relatively expensive since they were structurally more complex than a cannon, due to all the barrels and ignition fuses, and each barrel had to be individually maintained and cleaned.

Pepperbox

A pepper-box gun or "pepperbox revolver" has three or more barrels revolving around a central axis, and gets the name from its resemblance to the household pepper shakers. It has existed in all ammunition systems:

A pepper-box gun or "pepperbox revolver" has three or more barrels revolving around a central axis, and gets the name from its resemblance to the household pepper shakers. It has existed in all ammunition systems: matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befor ...

, wheellock, flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also know ...

, snaplock

A snaplock is a type of lock for firing a gun or is a gun fired by such a lock.

A snaplock ignites the (usually muzzle-loading) weapon's propellant by means of sparks produced when a spring-powered cock strikes a flint down on to a piece of hard ...

, caplock

The percussion cap or percussion primer, introduced in the early 1820s, is a type of single-use percussion ignition device for muzzle loader firearm locks enabling them to fire reliably in any weather condition. This crucial invention gave rise ...

, pinfire, rimfire and centerfire. They were popular in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

from 1830 until the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, but the concept was introduced much earlier. After each shot, the user manually rotates a next barrel into alignment with the hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nails into wood, to shape metal (as wi ...

mechanism, and each barrel needs to be reloaded and maintained individually.

In the 15th century, there were design attempts to have several single-shot barrels attached to a stock, being fired individually by means of a match

A match is a tool for starting a fire. Typically, matches are made of small wooden sticks or stiff paper. One end is coated with a material that can be ignited by friction generated by striking the match against a suitable surface. Wooden mat ...

. Around 1790, pepperboxes were built on the basis of flintlock systems, notably by Nock in England and "Segallas" in Belgium. These weapons building on the success of the earlier two-barrel turnover pistols, were fitted with three, four or seven barrels. These early pepperboxes were manually rotated.

The invention of the percussion cap building on the innovations of the Rev. Alexander Forsyth

Alexander John Forsyth (28 December 1768 – 11 June 1843) was a Scottish Church of Scotland minister who first successfully used fulminating (or 'detonating') chemicals to prime gunpowder in fire-arms thereby creating what became known as per ...

's patent of 1807 (which ran until 1821), and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

allowed pepperbox revolvers to be mass-produced, making them more affordable than the early handmade guns previously only seen in possessions of the rich. Examples of these early weapons are the American three-barrel Manhattan pistol, the English Budding (probably the first English percussion pepperbox) and the Swedish Engholm. Most percussion pepperboxes have a circular flange around the rear of the cylinder to prevent the capped nipples being accidentally fired if the gun were to be knocked while in a pocket, or dropped and to protect the eyes from cap fragments.

Samuel Colt

Samuel Colt (; July 19, 1814 – January 10, 1862) was an American inventor, industrialist, and businessman who established Colt's Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company (now Colt's Manufacturing Company) and made the mass production of ...

owned a revolving three-barrel matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befor ...

musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

from British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, and an eight-barrel pepperbox shotgun was designed in 1967 but never went into production.

Derringer

The original

The original Philadelphia Deringer

A derringer is a small handgun that is neither a revolver nor a semi/ fully automatic pistol. It is not to be confused with mini-revolvers or pocket pistols, although some later derringers were manufactured with the pepperbox configuration. ...

was a small single-barrel, muzzleloading

Muzzleloading is the shooting sport of firing muzzleloading guns. Muzzleloading guns, both antique and reproduction, are used for target shooting, hunting, historical re-enactment and historical research. The sport originated in the United States ...

caplock

The percussion cap or percussion primer, introduced in the early 1820s, is a type of single-use percussion ignition device for muzzle loader firearm locks enabling them to fire reliably in any weather condition. This crucial invention gave rise ...

pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, a ...

designed by Henry Deringer (1786–1868) and produced from 1852 to 1868, and was a popular concealed carry single-shot handgun of the era widely copycat

Copycat refers to a person who copies some aspect of some thing or somebody else.

Copycat may also refer to:

Intellectual property rights

* Copyright infringement, use of another’s ideas or words without permission

* Patent infringement, a v ...

ted by competitors. However, it was the breechloading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally bre ...

over-and-under Remington Model 95

The Remington Model 95 is a double-barrel pocket pistol commonly recognized as a Derringer. The design was little changed during a production run of nearly 70 years through several financial reorganizations of the manufacturer causing repeating ...

, manufactured by Remington Arms

Remington Arms Company, LLC was an American manufacturer of firearms and ammunition, now broken into two companies, each bearing the Remington name. The firearms manufacturer is ''Remington Arms''. The ammunition business is called ''Remington ...

from 1866 to 1935, that has truly achieved widespread popularity to the point that it completely overshadowed all other designs and becoming synonymous with the word " derringer". It used a break action design with two single-shot barrels chamber for the .41 rimfire cartridge, and a cam on the hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nails into wood, to shape metal (as wi ...

alternated between the barrels. The Remington derringer design is still being manufactured today by American Derringer, Bond Arms and Cobra Arms

Cobra Firearms, also known as Cobra Arms and officially as Cobra Enterprises of Utah, Inc. was an American firearms manufacturer based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Cobra Firearms was distantly related to the "Ring of Fire" companies of inexpensive fi ...

, and used by Cowboy Action Shooting reenactors as well as a concealed-carry weapon.

The Sharps Derringers were four-barrel derringers with a revolving firing pin (often called the "Sharps Pepperbox" despite not of a revolving-barrel design) first patented in 1849, but were not made until 1859 until Christian Sharps patented a more practical design. When loading and reloading, the four barrels slide forward open the breech. Production of these came to an end with the death of Christian Sharps in 1874.

Modern derringer designs are almost all multi-barrelled, essentially making them handheld compact volley guns. The COP 357

The COP .357 is a 4-shot Derringer-type pistol chambered for .357 Magnum. The double-action weapon is about twice as wide, and substantially heavier than the typical .25 automatic pistol, though its relatively compact size and powerful cartridge ...

is a .357 Magnum

The .357 Smith & Wesson Magnum, .357 S&W Magnum, .357 Magnum, or 9×33mmR as it is known in unofficial metric designation, is a smokeless powder cartridge with a bullet diameter. It was created by Elmer Keith, Phillip B. Sharpe, and Douglas B. ...

-caliber four-barrel (2×2), double-action hammerless

A hammerless firearm is a firearm that lacks an exposed hammer (firearm), hammer or hammer spur. Although it may not literally lack a hammer, it lacks a hammer that the user can pull directly. One of the disadvantages of an exposed hammer spur i ...

derringer introduced in 1984, and not much larger than a .25 ACP

The .25 ACP ( Automatic Colt Pistol) (6.35×16mmSR) is a semi-rimmed, straight-walled centerfire pistol cartridge introduced by John Browning

John Moses Browning (January 23, 1855 – November 26, 1926) was an American firearm designe ...

semi-automatic pistol

A semi-automatic pistol is a type of repeating single-chamber handgun ( pistol) that automatically cycles its action to insert the subsequent cartridge into the chamber (self-loading), but requires manual actuation of the trigger to actu ...

. A smaller-caliber .22 Magnum

The .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire, also called .22 WMR, .22 Magnum, .22 WMRF, .22 MRF, or .22 Mag, is a rimfire cartridge. Originally loaded with a bullet weight of delivering velocities in the range from a rifle barrel, .22 WMR is now loaded ...

"Mini COP" was also made by American Derringer.

DoubleTap Defense introduced the double-barreled (over-under), double-action hammerless DoubleTap derringer in 2012. The name comes from the double tap shooting technique, in which two consecutive shots are quickly fired at the same target before engaging the next one. These derringers also hold two extra rounds of cartridge in the grip, allegedly drawing inspiration from the FP-45 Liberator

The FP-45 Liberator is a pistol manufactured by the United States military during World War II for use by resistance forces in occupied territories. The ''Liberator'' was never issued to American or other Allied troops, and there are few docume ...

pistol.

Double-barrel shotgun

By 1790, Joseph Manton, acknowledged as the “father of the modern shotgun”, first brought together all the facets of the contemporary

By 1790, Joseph Manton, acknowledged as the “father of the modern shotgun”, first brought together all the facets of the contemporary flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also know ...

shotguns into the form of the modern double-barreled shotguns. Soon, caplock

The percussion cap or percussion primer, introduced in the early 1820s, is a type of single-use percussion ignition device for muzzle loader firearm locks enabling them to fire reliably in any weather condition. This crucial invention gave rise ...

ignition replaced flintlock, and then rather quickly, was replaced by the self-contained shell cartridge.

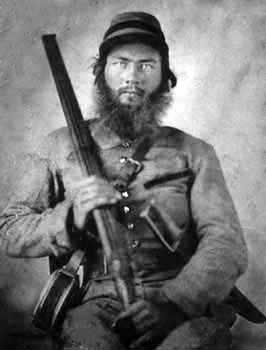

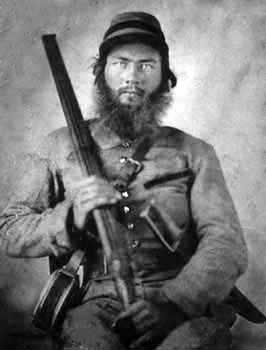

During the 19th century, shotguns were mainly employed by cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

units, as mounted units favored its moving target effectiveness, and devastating close-range firepower. Both sides of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

employed shotguns, and the U.S. Cavalry

The United States Cavalry, or U.S. Cavalry, was the designation of the mounted force of the United States Army by an act of Congress on 3 August 1861.Price (1883) p. 103, 104 This act converted the U.S. Army's two regiments of dragoons, one r ...

used them extensively during the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

. Shotguns also remained popular with citizen militias, guards (e.g. the shotgun messengers) and lawmen as a self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force ...

weapon, and became one of the many symbols of the American Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

.

In 1909, Boss & Co. introduced the over-and-under shotgun, which has remained the more popular configuration for double-barreled shotguns. Nowadays the pump-action

Pump action or slide action is a repeating firearm action that is operated manually by moving a sliding handguard on the gun's forestock. When shooting, the sliding forend is pulled rearward to eject any expended cartridge and typically to co ...

and semi-automatic shotgun

A semi-automatic shotgun is a repeating shotgun with a semi-automatic action, i.e. capable of automatically chambering a new shell after each firing, but requires individual trigger-pull to manually actuate each shot. Semi-automatic shotguns ...

s have taken over most roles in civilian home defense, law enforcement and military usages, though the over-and-under shotguns still remain popular for waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which ...

/ upland hunting and clay pigeon shooting

Clay pigeon shooting, also known as clay target shooting, is a shooting sport involving shooting a firearm at special flying targets known as clay pigeons, or clay targets.

The terminology commonly used by clay shooters often relates to time ...

.

Double rifle

The development of the double rifle has always followed the development of the double-barrelled shotgun, the two are generally very similar but the stresses of firing a solid projectile are far greater than shot. The first double-barrelled muskets were created in the 1830s when deer stalking became popular in Scotland. Previously single barrelled weapons had been used but, recognising the need for a rapid second shot to dispatch a wounded animal, double-barrelled muskets were built along the same format as double-barrelled shotguns already in common use. These first double-barrelled weapons wereblack powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars.

History

Early firearms had smoothly bored barrels that fired projectiles without signi ...

muzzleloaders built with either flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also know ...

or percussion cap ignition systems. Whilst true rifling

In firearms, rifling is machining helical grooves into the internal (bore) surface of a gun's barrel for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting to stabilize the ...

dates from the mid 16th century, the invention of the express rifle by James Purdey "the Younger" in 1856 allowed for far greater muzzle velocities to be achieved through a rifled longarm, significantly improving the trajectory and as such greatly improving the range of these rifles. These express rifles had two deep opposing grooves which were wide and deep enough to prevent the lead bullets from stripping the rifling if fired at high velocities, a significant problem previously.

Various experimental breech loaders had been in existence since the 16th century, however developments such as the Ferguson rifle

The Ferguson rifle was one of the first breech-loading rifles to be put into service by the British military. It fired a standard British carbine ball of .615" calibre and was used by the British Army in the American Revolutionary War at the Battle ...

in the 1770s and early pinfire cartridges in the 1830s had little impact on sporting rifles due to their experimental nature, expense and the extraordinary strength and reliability of the percussion muzzleloader. In 1858, Westley Richards

Westley Richards is a British manufacturer of guns and rifles and also a well established gunsmith. The company was founded in 1812 by William Westley Richards, who was responsible for the early innovation of many rifles used in wars featuring ...

patented the break open, top leaver breech loading action, whilst a useful development these early break open designs had a great deal of elasticity in the action and upon firing they sprung open slightly, a problem that gradually worsened with repeated firing and with more powerful cartridges. Many gunmakers tried various methods to rectify this problem, all to little avail until Westley Richards invented the "Dolls head" lock in 1862 which greatly improved rigidity, this was followed by James Purdey's under-locking mechanism in 1863 and W.W. Greener's "Wedge fast" system in 1873, finally the basic break open action known to this day had the strength required to meet the stresses of large-bore projectiles. By 1914, triple, quadruple and even quintuple locking designs could be found in various proprietary actions.

By 1900 the boxlock and sidelock hammerless actions had largely superseded the hammer rifles and, with the addition of ejectors and assisted opening, the basic design of the double rifle has changed little to this day. Incidentally, it was Westley Richards who invented the first reliable safety catch for doubles, ejectors, the single selective trigger and the special extractors that enabled rimless cartridges to be used in double rifles, all features found in modern double rifles.

After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, a combination of increased labour costs and a shrinking British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

saw an end to the demand for handcrafted sporting rifles and the double rifle was largely supplanted by the bolt action

Bolt-action is a type of manual firearm action that is operated by ''directly'' manipulating the bolt via a bolt handle, which is most commonly placed on the right-hand side of the weapon (as most users are right-handed).

Most bolt-actio ...

rifle. It was not until the 1980s and 1990s, with the emergence of the big game hunting industry in Southern Africa that the production of double rifles resumed at a steady rate, driven largely by demand from American sportsmen.

Rotary gun

The Gatling gun is one of the best-known early rapid-fire weapons and a forerunner of the modern

The Gatling gun is one of the best-known early rapid-fire weapons and a forerunner of the modern machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ar ...

s and automatic rotary gun

A rotary cannon, rotary autocannon, rotary gun or Gatling cannon, is any large- caliber multiple-barreled automatic firearm that uses a Gatling-type rotating barrel assembly to deliver a sustained saturational direct fire at much greater ra ...

s. Invented by Richard Gatling, it saw occasional use by the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

forces during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

in the 1860s, which was the first time it was employed in combat. Later, it was used again in numerous military conflicts, such as the Boshin War, the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

, and the assault on San Juan Hill

San Juan Hill is a series of hills to the east of Santiago, Cuba, running north to south. The area is known as the San Juan Heights or in Spanish ''Alturas de San Juan'' before Spanish–American War of 1898, and are now part of Lomas de San Ju ...

during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. It was also used by the Pennsylvania militia in episodes of the Great Railroad Strike

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

of 1877, specifically in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

.

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a pepperbox

The pepper-box revolver or simply pepperbox (also "pepper-pot", from its resemblance to the household pepper shakers) is a multiple-barrel firearm, mostly in the form of a handgun, that has three or more gun barrels in a coaxially revolving m ...

-like multi-barrel assembly whose design facilitated better cooling and synchronized the firing-reloading sequence. The gun was operated by manually turning a crank-like side-handle, which was gear

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth (called ''cogs''), which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit (convert) torque and speed. The basic ...

ed to rotate the entire barrel assembly. Each barrel is coupled to a cam

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bin ...

-driven bolt, which picked up a single cartridge

Cartridge may refer to:

Objects

* Cartridge (firearms), a type of modern ammunition

* ROM cartridge, a removable component in an electronic device

* Cartridge (respirator), a type of filter used in respirators

Other uses

* Cartridge (surname), a ...

and then fired off the shot when reaching certain positions in the rotation, afterwards it ejected the spent cartridge case

A cartridge or a round is a type of pre-assembled firearm ammunition packaging a projectile ( bullet, shot, or slug), a propellant substance (usually either smokeless powder or black powder) and an ignition device ( primer) within a metal ...

and allowed the empty barrel to cool somewhat before loading a new round and repeating the cycle. This cyclic configuration overlapped the operation of the barrel-action groups, and allowed higher rates of fire to be achieved without each barrel overheating.

Richard Gatling later replaced the hand-cranked mechanism of a rifle-caliber Gatling gun with an electric motor

An electric motor is an electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a wire winding to generate for ...

, a relatively new invention at the time. Even after he slowed down the mechanism, the new electric motor-powered Gatling gun had a theoretical rate of fire of 3,000 rounds per minute, roughly three times the maximum rate of a typical modern single-barreled machine gun. Gatling's electric-powered design received U.S. Patent #502,185 on July 25, 1893, but despite the improvements, Gatling guns soon fell into disuse after cheaper, lighter-weight and more reliable recoil- and gas-operated machine guns were invented; Gatling himself went bankrupt for a period.

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, several German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

companies were working on externally powered guns for use in aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engine ...

. Of those, the best-known today is perhaps the Fokker-Leimberger

The Fokker-Leimberger was an externally powered, 12-barrel rifle-caliber rotary gun developed in Germany during the First World War. The action of the Fokker-Leimberger differed from that of a Gatling in that it employed a rotary split-breech de ...

, an externally powered 12-barrel rotary gun using the 7.92×57mm Mauser rounds; it was claimed to be capable of firing over 7,000 rpm, but suffered from frequent cartridge-case ruptures due to its "nutcracker", rotary split-breech design, which is fairly different from that of a Gatling. None of these German guns went into production during the war, although a competing Siemens prototype (possibly using a different action) which was tried on the Western Front scored a victory in aerial combat. The British also experimented with this type of split-breech during the 1950s, but they were also unsuccessful.

In the 1960s, the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

began exploring modern variants of the electric-powered, rotating barrel Gatling-style weapons for use in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

. American forces in the Vietnam War, which used helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

s as one of the primary means of transporting soldiers and equipment through the dense tropical jungles, found that the thinly-armored helicopters were very vulnerable to small arms fire and rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) attacks when they slowed to land. Although helicopters had mounted single-barrel machine guns, using them to repel attackers hidden in the dense jungle foliage often led to barrels quickly overheating or the action jamming.

In order to develop a weapon with a more reliable, higher rate of fire, General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable en ...

designers scaled down the rotating-barrel 20 mm

20 mm caliber is a specific size of popular autocannon ammunition. It is typically used to distinguish smaller-caliber weapons, commonly called "guns", from larger-caliber "cannons" (e.g. machine gun vs. autocannon). All 20 mm cartridges h ...

M61 Vulcan

The M61 Vulcan is a hydraulically, electrically, or pneumatically driven, six- barrel, air-cooled, electrically fired Gatling-style rotary cannon which fires rounds at an extremely high rate (typically 6,000 rounds per minute). The M61 and i ...

rotary cannon for the 7.62×51mm NATO ammunition. The resulting weapon, the M134 Minigun

The M134 Minigun is an American 7.62×51mm NATO six-barrel rotary machine gun with a high rate of fire (2,000 to 6,000 rounds per minute). It features a Gatling-style rotating barrel assembly with an external power source, normally an electric ...

, could fire up to 6,000 rounds per minute without overheating. The gun has a selectably variable rate of fire specified to fire at rates of up to 6,000 rpm, with most applications set at rates between 3,000-4,000 rounds per minute.

The Minigun was mounted on Hughes OH-6 Cayuse and Bell OH-58 Kiowa side pods; in the turret and on pylon pods of Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters; and on door, pylon and pod mounts on Bell UH-1 Iroquois transport helicopter

A military transport aircraft, military cargo aircraft or airlifter is a military-owned transport aircraft used to support military operations by airlifting troops and military equipment. Transport aircraft are crucial to maintaining supply l ...

s. Several larger aircraft were outfitted with Miniguns specifically for close air support: the Cessna A-37 Dragonfly

The Cessna A-37 Dragonfly, or Super Tweet, is an American light attack aircraft developed from the T-37 Tweet basic trainer in the 1960s and 1970s by Cessna of Wichita, Kansas. The A-37 was introduced during the Vietnam War and remained in pe ...

with an internal gun and with pods on wing hardpoints; and the Douglas A-1 Skyraider

The Douglas A-1 Skyraider (formerly known as the AD Skyraider) is an American single-seat attack aircraft in service from 1946 to the early 1980s. The Skyraider had an unusually long career, remaining in front-line service well into the Jet Age ...

, also with pods on wing hardpoints. Other famous gunship aircraft were the Douglas AC-47 Spooky

The Douglas AC-47 Spooky (also nicknamed "Puff, the Magic Dragon") was the first in a series of fixed-wing gunships developed by the United States Air Force during the Vietnam War. It was designed to provide more firepower than light and mediu ...

, the Fairchild AC-119

The Fairchild AC-119G Shadow and AC-119K Stinger were twin-engine piston-powered gunships developed by the United States during the Vietnam War. They replaced the Douglas AC-47 Spooky and operated alongside the early versions of the AC-130 Sp ...

and the Lockheed AC-130

The Lockheed AC-130 gunship is a heavily armed, long-endurance, attack aircraft, ground-attack variant of the C-130 Hercules transport, fixed-wing aircraft. It carries a wide array of ground-attack weapons that are integrated with sophisticate ...

.

See also

* * – Rifle with two parallel barrels * * * * – Portable weapons that can be carried and used by an individual person.References

{{Multiple barrel firearms Firearm actions Multiple-barrel firearms