The diplomatic career of Muhammad ( – 8 June 632) encompasses Muhammad's leadership over the growing

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

community (''

Ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

'') in early Arabia and his correspondences with the rulers of other nations in and around Arabia. This period was marked by the change from the customs of the period of ''

Jahiliyyah

The Age of Ignorance ( ar, / , " ignorance") is an Islamic concept referring to the period of time and state of affairs in Arabia before the advent of Islam in 610 CE. It is often translated as the "Age of Ignorance". The term ''jahiliyyah' ...

'' in

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

to an early Islamic system of governance, while also setting the defining principles of

Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ex ...

in accordance with

Sharia law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

and an

Islamic theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

.

The two primary Arab tribes of Medina, the

Aws

Amazon Web Services, Inc. (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon that provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and APIs to individuals, companies, and governments, on a metered pay-as-you-go basis. These cloud computing web services provide d ...

and the

Khazraj

The Banu Khazraj ( ar, بنو خزرج) is a large Arab tribe based in Medina. They were also in Medina during Muhammad's era.

The Banu Khazraj are a South Arabian tribe that were pressured out of South Arabia in the Karib'il Watar 7th cent ...

, had been battling each other for the control of Medina for more than a century before

Muhammad's arrival.

[Watt. al-Aus; Encyclopaedia of Islam] With the pledges of al-Aqaba, which took place near

Mina, Muhammad was accepted as the common leader of Medina by the Aws and Khazraj and he addressed this by establishing the

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

upon his arrival; a document which regulated interactions between the different factions, including the Arabian Jews of Medina, to which the signatories agreed. This was a different role for him, as he was only a religious leader during his time in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

. The result was the eventual formation of a united community in

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, as well as the political supremacy of Muhammad,

[Buhl; Welch. Muhammad; Encyclopaedia of Islam] along with the beginning of a ten-year long diplomatic career.

In the final years before his death, Muhammad established communication with other leaders through

letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alpha ...

,

[Irfan Shahid, ]Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is '' Adab'', which is derived from ...

to the end of the Umayyad period

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

, Journal of the American Oriental Society

The American Oriental Society was chartered under the laws of Massachusetts on September 7, 1842. It is one of the oldest learned societies in America, and is the oldest devoted to a particular field of scholarship.

The Society encourages basi ...

, Vol 106, No. 3, p.531 envoys,

[ al-Mubarakpuri(2002) p. 412] or by visiting them personally, such as at

Ta’if,

[Watt (1974) p. 81] Muhammad intended to spread the message of Islam outside of Arabia. Instances of preserved written correspondence include letters to

Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revol ...

, the

Negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch, and

Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

, among other leaders. Although it is likely that Muhammad had initiated contact with other leaders within the

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

, some have questioned whether letters had been sent beyond these boundaries.

[Forward (1998) pp. 28—29]

The main defining moments of Muhammad's career as a diplomat are the

Pledges at al-Aqabah, the

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

, and the

Treaty of Hudaybiyyah

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah ( ar, صُلح ٱلْحُدَيْبِيَّة, Ṣulḥ Al-Ḥudaybiyyah) was an event that took place during the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was a pivotal treaty between Muhammad, representing the state of ...

. Muhammad reportedly used a silver

seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

on letters sent to other notable leaders which he sent as

invitations to the religion of Islam.

Early invitations to Islam

Migration to Abyssinia

Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading

tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

of Mecca, the

Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qu ...

. Although Muhammad himself was safe from persecution due to protection from his uncle,

Abu Talib (a leader of the

Banu Hashim

)

, type = Qurayshi Arab clan

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, nisba = al-Hashimi

, location = Mecca, Hejaz Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa

, descended = Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

, parent_tribe = ...

, one of the main clans that formed the Quraysh), some of his followers were not in such a position. A number of Muslims were mistreated by the Quraysh, some reportedly beaten, imprisoned, or starved. In 615, Muhammad resolved to send fifteen Muslims to emigrate to

Axum

Axum, or Aksum (pronounced: ), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015).

It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire, a naval and trading power that ruled the whole regio ...

to receive protection under the

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

ruler, the

Negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch, ,

Aṣḥama ibn Abjar

Armah ( gez, አርማህ) or Aṣḥamah ( ar, أَصْحَمَة), commonly known as Najashi ( ar, النَّجَاشِيّ, translit=An-najāshī), was the ruler of the Kingdom of Aksum who reigned from 614–631 CE. He is primarily known th ...

.

[Forward (1998) p. 15] Emigration was a means through which some of the Muslims could escape the difficulties and persecution faced at the hands of the Quraysh,

it also opened up new trading prospects.

Ja'far ibn Abu Talib as Muhammad's ambassador

The Quraysh, on hearing the attempted emigration, dispatched a group led by

'Amr ibn al-'As

( ar, عمرو بن العاص السهمي; 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and was assigned import ...

and Abdullah ibn Abi Rabi'a ibn Mughira in order to pursue the fleeing Muslims. The Muslims reached Axum before they could capture them, and were able to seek the safety of the Negus in

Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Saint ...

. The Qurayshis appealed to the Negus to return the Muslims and they were summoned to an audience with the Negus and his bishops as a representative of Muhammad and the Muslims,

Ja`far ibn Abī Tālib acted as the ambassador of the Muslims and spoke of Muhammad's achievements and quoted

Qur'anic verses related to Islam and

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

, including some from

Surah Maryam.

[van Donzel. al-Nadjāshī; Encyclopaedia of Islam] Ja`far ibn Abī Tālib is quoted according to

Islamic tradition as follows:

The Negus, seemingly impressed, consequently allowed the migrants to stay, sending back the emissaries of Quraysh.

It is also thought that the Negus may have converted to Islam. The Christian subjects of the Negus were displeased with his actions, accusing him of leaving Christianity, although the Negus managed to appease them in a way which, according to

Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

, could be described as favourable towards Islam.

Having established friendly relations with the Negus, it became possible for Muhammad to send another group of migrants, such that the number of Muslims living in Abyssinia totalled around one hundred.

Pre-Hijra invitations to Islam

Ta'if

In early June 619, Muhammad set out from Mecca to

travel to Ta'if in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of

Banu Thaqif

The Banu Thaqif ( ar, بنو ثقيف, Banū Thaqīf) is an Arab tribe which inhabited, and still inhabits, the city of Ta'if and its environs, in modern Saudi Arabia, and played a prominent role in early Islamic history.

During the pre-Islamic ...

(such as

'Abd-Ya-Layl ibn 'Amr). The main dialogue during this visit is thought to have been the invitation by Muhammad for them to accept Islam, while contemporary historian

Montgomery Watt

William Montgomery Watt (14 March 1909 – 24 October 2006) was a Scottish Orientalist, historian, academic and Anglican priest. From 1964 to 1979, he was Professor of Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Watt was one ...

observes the plausibility of an additional discussion about wresting the Meccan

trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

s that passed through Ta'if from Meccan control.

The reason for Muhammad directing his efforts towards Ta'if may have been due to the lack of positive response from the people of Mecca to his message until then.

In rejection of his message, and fearing that there would be reprisals from Mecca for having hosted Muhammad, the groups involved in meeting with Muhammad began to incite townsfolk to pelt him with stones.

Having been beset and pursued out of Ta'if, the wounded Muhammad sought refuge in a nearby

orchard

An orchard is an intentional plantation of trees or shrubs that is maintained for food production. Orchards comprise fruit- or nut-producing trees which are generally grown for commercial production. Orchards are also sometimes a feature of ...

. Resting under a

grape vine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 79 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, ...

, it is here that he invoked

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, seeking comfort and protection.

[al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 163—166]

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad on his way back to Mecca was met by the

angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles ...

Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

and the angels of the mountains surrounding Ta'if, and was told by them that if he willed, Ta'if would be crushed between the mountains in revenge for his mistreatment. Muhammad is said to have rejected the proposition, saying that he would pray in the hopes of succeeding generations of Ta'if coming to accept

Islamic monotheism

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single mo ...

.

Pledges at al-'Aqaba

In the summer of 620 during the pilgrimage season, six men of the

Khazraj

The Banu Khazraj ( ar, بنو خزرج) is a large Arab tribe based in Medina. They were also in Medina during Muhammad's era.

The Banu Khazraj are a South Arabian tribe that were pressured out of South Arabia in the Karib'il Watar 7th cent ...

travelling from Medina came into contact with Muhammad. Having been impressed by his message and character, and thinking that he could help bring resolution to the problems being faced in Medina, five of the six men returned to Mecca the following year bringing seven others. Following their

conversion to Islam

Conversion to Islam is accepting Islam as a religion or faith and rejecting any other religion or irreligion. Requirements

Converting to Islam requires one to declare the '' shahādah'', the Muslim profession of faith ("there is no god but Allah ...

and attested belief in Muhammad as the messenger of God, the twelve men pledged to obey him and to stay away from a number of Islamically sinful acts. This is known as the ''First Pledge of al-'Aqaba'' by Islamic historians.

[Watt (1974) p. 83] Following the pledge, Muhammad decided to dispatch a Muslim ambassador to Medina and he chose

Mus'ab ibn 'Umair for the position, in order to teach people about Islam and invite them to the religion.

With the slow but steady conversion of persons from both the Aws and Khazraj present in

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, 75 Medinan Muslims came as pilgrims to Mecca and secretly convened with Muhammad in June 621, meeting him at night. The group made to Muhammad the ''Second Pledge of al-'Aqaba'', also known as the ''Pledge of War''.

The people of Medina agreed to the conditions of the first pledge, with new conditions including included obedience to Muhammad, the

enjoinment of good and forbidding evil. They also agreed to help Muhammad in war and asked of him to declare war on the Meccans, but he refused.

Some western academics are noted to have questioned whether or not a second pledge had taken place, although

William M. Watt argues that there must have been several meetings between the pilgrims and Muhammad on which the basis of his move to Medina could be agreed upon.

Muhammad as the leader of Medina

Pre-Hijra Medinan society

The demography of Medina before Muslim migration consisted mainly of two

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

tribes; the

Aws

Amazon Web Services, Inc. (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon that provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and APIs to individuals, companies, and governments, on a metered pay-as-you-go basis. These cloud computing web services provide d ...

and the

Khazraj

The Banu Khazraj ( ar, بنو خزرج) is a large Arab tribe based in Medina. They were also in Medina during Muhammad's era.

The Banu Khazraj are a South Arabian tribe that were pressured out of South Arabia in the Karib'il Watar 7th cent ...

; and at least three

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

tribes: the

Qaynuqa,

Nadir

The nadir (, ; ar, نظير, naẓīr, counterpart) is the direction pointing directly ''below'' a particular location; that is, it is one of two vertical directions at a specified location, orthogonal to a horizontal flat surface.

The direc ...

, and

Qurayza.

Medinan society, for perhaps decades, had been scarred by feuds between the two main Arab tribes and their sub-clans. The

Jewish tribes had at times formed their own alliances with either one of the Arab tribes. The oppressive policy of the Khazraj who at the time had assumed control over Medina, forced the Jewish tribes, Nadir and Qurayza, into an alliance with the Aws, who had been significantly weakened. The culmination of this was the

Battle of Bu'ath

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

in 617, in which the Khazraj and their allies, the Qaynuqa, had been soundly defeated by the coalition of Aws and its supporters.

Although formal combat between the two clans had ended, hostilities between them continued even up until Muhammad's arrival in Medina. Muhammad had been invited by some Medinans, who had been impressed by his religious preaching and manifest trustworthiness, as an arbitrator to help reduce the prevailing factional discord.

[Forward (1998) p. 19] Muhammad's task would thus be to form a united community out of these heterogeneous elements, not only as a religious preacher, but as a political and diplomatic leader who could help resolve the ongoing disputes.

The culmination of this was the

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

.

Constitution of Medina

After the pledges at al-'Aqaba, Muhammad received promises of protection from the people of Medina and he

migrated to Medina with a group of his

followers in 622, having escaped the forces of Quraysh. They were given shelter by members of the indigenous community known as the

Ansar. After having established the first

mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

in Medina (the

''Masjid an-Nabawi'') and obtaining residence with

Abu Ayyub al-Ansari

Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ( ar, أبو أيوب الأنصاري, Abū Ayyūb al-Anṣārī, tr, Ebu Eyyûb el-Ensarî, died c. 674) — born Khalid ibn Zayd ibn Kulayb ibn Tha'laba ( ar, خالد ابن زيد ابن كُليب ابن ثعلبه, Kh ...

, he set about the establishment of a pact known as the

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

(). This document was a unilateral declaration by Muhammad, and deals almost exclusively with the civil and political relations of the citizens among themselves and with the outside.

[Bernard Lewis, ''The Arabs in History,'' page 43.]

The Constitution, among other terms, declared:

* the formation of a nation of Muslims (''

Ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

'') consisting of the ''

Muhajirun

The ''Muhajirun'' ( ar, المهاجرون, al-muhājirūn, singular , ) were the first converts to Islam and the Islamic prophet Muhammad's advisors and relatives, who emigrated with him from Mecca to Medina, the event known in Islam as the '' Hij ...

'' from the

Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qu ...

, the

''Ansar'' of Yathrib (

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

) and other Muslims of Yathrib.

* the establishment of a system of prisoner exchange in which the rich were no longer treated differently from the poor (as was the custom in

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

)

* all the signatories would unite as one in the defense of the city of Medina, declared the Jews of Aws equal to the Muslims, as long as they were loyal to the charter.

* the protection of Jews from

religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or their lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within societies to alienate o ...

* that the declaration of war can only be made by

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

.

Impact of the Constitution

The source of authority was transferred from public opinion to God.

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

writes the community at Medina became a new kind of tribe with Muhammad as its

sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

, while at the same time having a religious character. Watt argues that Muhammad's authority had not extended over the entirety of Medina at this time, such that in reality he was only the religious leader of Medina, and his political influence would only become significant after the

Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr ( ar, غَزْوَةُ بَدِرْ ), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (, ) in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the present-day city of Badr, Al Madinah Provin ...

in 624. Lewis opines that Muhammad's assumption of the role of statesman was a means through which the objectives of

prophethood

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

could be achieved. The constitution, although recently signed, was soon to be rendered obsolete due to the rapidly changing conditions in Medina,

and with the exile of two of the Jewish tribes and the execution of the third after having been accused of breaching the terms of agreement.

The signing of the constitution could be seen as indicating the formation of a united community, in many ways, similar to a

federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

of

nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic clans and tribes, as the signatories were bound together by solemn agreement. The community, however, now also had a

religious foundation.

[Watt (1974) p. 94—95] Extending this analogy, Watt argues that the functioning of the community resembled that of a tribe, such that it would not be incorrect to call the community a kind of "super-tribe".

The signing of the constitution itself displayed a degree of diplomacy on part of Muhammad, as although he envisioned a society eventually based upon a religious outlook, practical consideration was needed to be inclusive instead of exclusive of the varying social elements.

Union of the Aws and Khazraj

Both the

Aws

Amazon Web Services, Inc. (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon that provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and APIs to individuals, companies, and governments, on a metered pay-as-you-go basis. These cloud computing web services provide d ...

and

Khazraj

The Banu Khazraj ( ar, بنو خزرج) is a large Arab tribe based in Medina. They were also in Medina during Muhammad's era.

The Banu Khazraj are a South Arabian tribe that were pressured out of South Arabia in the Karib'il Watar 7th cent ...

had progressively converted to Islam, although the latter had been more enthusiastic than the former; at the second pledge of al-'Aqaba, 62 Khazrajis were present, in contrast to the 3 members of the Aws; and at the Battle of Badr, 175 members of the Khazraj were present, while the Aws numbered only 63. Subsequently, the hostility between the Aws and Khazraj gradually diminished and became unheard of after Muhammad's death.

According to

Muslim scholar al-Mubarakpuri, the 'spirit of brotherhood' as insisted by Muhammad amongst Muslims was the means through which a new society would be shaped.

The result was Muhammad's increasing influence in Medina, although he was most probably only considered a political force after the Battle of Badr, more so after the

Battle of Uhud

The Battle of Uhud ( ar, غَزْوَة أُحُد, ) was fought on Saturday, 23 March 625 AD (7 Shawwal, 3 AH), in the valley north of Mount Uhud.Watt (1974) p. 136. The Qurayshi Meccans, led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, commanded an army of 3,000 ...

where he was clearly in political ascendency. To attain complete control over Medina, Muhammad would have to exercise considerable political and

military skills, alongside religious skills over the coming years.

Treaty of Hudaybiyyah

Muhammad's attempt at performing the 'Umrah

In March 628, Muhammad saw himself in a dream performing the ''

Umrah

The ʿUmrah ( ar, عُمْرَة, lit=to visit a populated place) is an Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca (the holiest city for Muslims, located in the Hejazi region of Saudi Arabia) that can be undertaken at any time of the year, in contrast to t ...

'' (lesser pilgrimage), and so prepared to travel with his followers to Mecca in the hopes of fulfilling this vision.

He set out with a group of around 1,400 pilgrims (in the traditional

''ihram'' garb). On hearing of the Muslims travelling to Mecca for pilgrimage, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 fighters in order to halt the approaching party. In no position to fight, Muhammad evaded the cavalry by taking a more difficult route through the hills north of

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just west of Mecca.

[Watt. al-Hudaybiya; Encyclopaedia of Islam]

It was at Hudaybiyyah that a number of envoys went to and fro in order to negotiate with the Quraysh. During the negotiations,

Uthman ibn Affan was chosen as an envoy to convene with the leaders in Mecca, on account of his high regard amongst the Quraysh. On his entry into Mecca, rumours ignited among the Muslims that 'Uthman had subsequently been murdered by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the ''Pledge of Good Pleasure'' () or the ''Pledge Under The Tree''.

The incident was mentioned in the

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

in Surah 48:

Signing of the Treaty

Soon afterwards, with the rumour of Uthman's slaying proven untrue, negotiations continued and a treaty was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh. Conditions of the treaty included:

* the Muslims' postponement of the lesser pilgrimage until the following year

* a pact of mutual non-aggression between the parties

* a promise by Muhammad to return any member of Quraysh (presumably a minor or woman) fleeing from Mecca without the permission of their parent or guardian, even if they be Muslim.

Some of Muhammad's followers were upset by this agreement, as they had insisted that they should complete the pilgrimage they had set out for. Following the signing of the treaty, Muhammad and the pilgrims

sacrificed the animals they had brought for it, and proceeded to return to Medina.

It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty.

These benefits, according to Islamic historian Welch Buhl, included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity, boding well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.

Violation of the Treaty

The treaty was set to expire after 10 years, but was broken after only 10 months.

According to the terms of the treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the Arab tribes were given the option to join either of the parties, the Muslims or Quraish. Should any of these tribes face aggression, the party to which it was allied would have the right to retaliate. As a consequence,

Banu Bakr

The Banu Bakr bin Wa'il ( ar, بنو بكر بن وائل '), or simply Banu Bakr, were an Arabian tribe belonging to the large Rabi'ah branch of Adnanite tribes, which also included Abd al-Qays, Anazzah, Taghlib. The tribe is reputed to have e ...

joined Quraish, and the

Banu Khuza‘ah joined Muhammed.

Banu Bakr attacked

Banu Khuza'a

The Banū Khuzāʿah ( ar, بنو خزاعة singular ''Khuzāʿī'') is the name of an Azdite, Qaḥṭānite tribe, which is one of the main ancestral tribes of the Arabian Peninsula. They ruled Mecca for a long period, prior to the Islamic ...

h at al-Wateer in Sha'baan 8 AH and it was revealed that the Quraish helped Banu Bakr with men and arms taking advantage of the cover of the night.

Pressed by their enemies, the tribesmen of Khuza‘ah sought the

Holy Sanctuary, but here too, their lives were not spared, and Nawfal, the chief of Banu Bakr, chasing them in the sanctified area, massacred his adversaries.

Correspondence with other leaders

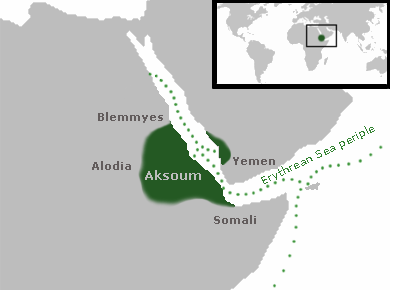

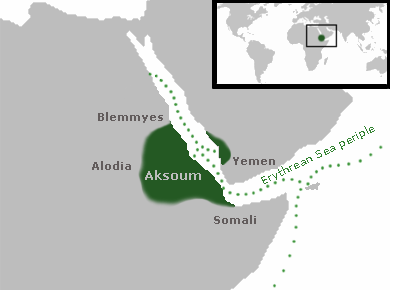

There are instances according to Islamic tradition where Muhammad is thought to have sent letters to other heads of state during the

Medinan phase of his life. Amongst others, these included the

Negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch, of

Axum

Axum, or Aksum (pronounced: ), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015).

It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire, a naval and trading power that ruled the whole regio ...

, the

Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as ...

Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revol ...

(), the ''

Muqawqis'' of

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

and the

Sasanid emperor Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

(). There has been controversy amongst academic scholars as to their authenticity.

[El-Cheikh (1999) pp. 5—21] According to

Martin Forward

Martin Forward is a British, Methodist Christian lecturer and author on religion and Professor of History at Aurora University, Illinois. He has taught Islam at the Universities of Leicester, Bristol and Cambridge, and had spent a period of time i ...

, academics have treated some reports with

skepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the p ...

, although he argues that it is likely that

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

had assumed correspondence with leaders within the

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

.

opines that the letters are forgeries and were designed to promote both the 'notion that Muhammad conceived of Islam as a universal religion and to strengthen the Islamic position against Christian polemic.' He further argues the unlikelihood of Muhammad sending such letters when he had not yet mastered Arabia.

Irfan Shahid

In Islam, ‘Irfan (Arabic/Persian/ Urdu: ; tr, İrfan), literally ‘knowledge, awareness, wisdom’, is gnosis. Islamic mysticism can be considered as a vast range that engulfs theoretical and practical and conventional mysticism, but the ...

, professor of the

Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and

Islamic literature

Islamic literature is literature written by Muslim people, influenced by an Islamic cultural perspective, or literature that portrays Islam. It can be written in any language and portray any country or region. It includes many literary forms incl ...

at

Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private research university in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll in 1789 as Georgetown College, the university has grown to comprise eleven undergraduate and graduate ...

, contends that dismissing the letters sent by Muhammad as forgeries is "unjustified", pointing to recent research establishing the historicity of the letter to

Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revol ...

as an example.

Letter to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire

A letter was sent from Muhammad to the emperor of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

,

Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revol ...

, through the Muslim envoy

Dihyah bin Khalifah al-Kalbi, although

Shahid

''Shaheed'' ( , , ; pa, ਸ਼ਹੀਦ) denotes a martyr in Islam. The word is used frequently in the Quran in the generic sense of "witness" but only once in the sense of "martyr" (i.e. one who dies for his faith); ...

suggests that Heraclius may never have received it.

He also advances that more positive sub-narratives surrounding the letter contain little credence. According to Nadia El Cheikh, Arab historians and chroniclers generally did not doubt the authenticity of Heraclius' letter due to the documentation of such letters in the majority of both early and later sources.

[Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5–21.] Furthermore, she notes that the formulation and the wordings of different sources are very close and the differences are ones of detail: They concern the date on which the letter was sent and its exact phrasing.

, an Islamic research scholar, argues for the authenticity of the letter sent to Heraclius, and in a later work reproduces what is claimed to be the original letter.

The account as transmitted by

Muslim historians is translated as follows:

According to Islamic reports, Muhammad dispatched

Dihyah al-Kalbi to carry the epistle to "

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

" through the government of

Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dara ...

after the

Byzantine defeat of the Persians and reconquest of Jerusalem.

[ Islamic sources say that after the letter was read to him, he was so impressed by it that he gifted the messenger of the epistle with robes and coinage.][ He then summoned ]Abu Sufyan ibn Harb

Sakhr ibn Harb ibn Umayya ibn Abd Shams ( ar, صخر بن حرب بن أمية بن عبد شمس, Ṣakhr ibn Ḥarb ibn Umayya ibn ʿAbd Shams; ), better known by his '' kunya'' Abu Sufyan ( ar, أبو سفيان, Abū Sufyān), was a prominent ...

to his court, at the time an adversary to Muhammad but a signatory to the then-recent Treaty of Hudaybiyyah

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah ( ar, صُلح ٱلْحُدَيْبِيَّة, Ṣulḥ Al-Ḥudaybiyyah) was an event that took place during the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was a pivotal treaty between Muhammad, representing the state of ...

, who was trading in Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

at the time. Asked by Heraclius about the man claiming to be a prophet, Abu Sufyan responded, speaking favorably of Muhammad's character and lineage and outlining some directives of Islam. Heraclius was seemingly impressed by what he was told of Muhammad, and felt that Muhammad's claim to prophethood was valid.Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to confirm if Muhammad's claim of prophethood was legitimate, and, after receiving the reply to his letter, called the Roman assembly saying, "If you desire salvation and the orthodox way so that your empire remain firmly established, then follow this prophet," to the rejection of the council.[ Heraclius eventually decided against conversion but the envoy was returned to Medina with the felicitations of the emperor.

Scholarly historians disagree with this account, arguing that any such messengers would have received neither an imperial audience or recognition, and that there is no evidence outside of Islamic sources suggesting that Haraclius had any knowledge of Islam.]

Letter to the Negus of Axum

The letter inviting Armah

Armah ( gez, አርማህ) or Aṣḥamah ( ar, أَصْحَمَة), commonly known as Najashi ( ar, النَّجَاشِيّ, translit=An-najāshī), was the ruler of the Kingdom of Aksum who reigned from 614–631 CE. He is primarily known th ...

, the Axumite king of Ethiopia/Abyssinia, to Islam had been sent by Amr bin 'Umayyah ad-Damri, although it is not known if the letter had been sent with Ja'far on the migration to Abyssinia

The migration to Abyssinia ( ar, الهجرة إلى الحبشة, translit=al-hijra ʾilā al-habaša), also known as the First Hijra ( ar, الهجرة الأولى, translit=al-hijrat al'uwlaa, label=none), was an episode in the early histor ...

or at a later date following the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah ( ar, صُلح ٱلْحُدَيْبِيَّة, Ṣulḥ Al-Ḥudaybiyyah) was an event that took place during the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was a pivotal treaty between Muhammad, representing the state of ...

. According to Hamidullah, the former may be more likely.Negus

Negus (Negeuce, Negoose) ( gez, ንጉሥ, ' ; cf. ti, ነጋሲ ' ) is a title in the Ethiopian Semitic languages. It denotes a monarch, was purported to accept Islam in a reply he wrote to Muhammad. According to Islamic tradition, the Muslims in Medina prayed the funeral prayer in absentia for the Negus on his death. It is possible that a further letter was sent to the successor of the late Negus.

Letter to the Muqawqis of Egypt

There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to Muqawqis. Some scholars such as Nöldeke consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value".

There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to Muqawqis. Some scholars such as Nöldeke consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value".[Öhrnberg; Mukawkis. Encyclopaedia of Islam.] Muslim historians, in contrast, generally affirm the historicity of the reports. The text of the letter (sent by Hatib bin Abu Balta'ah) according to Islamic tradition is translated as follows:

The Muqawqis responded by sending gifts to Muhammad, including two female slaves, Maria al-Qibtiyya

(), better known as or ( ar, مارية القبطية), or Mary the Copt, died 637, was an Egyptian woman who, along with her sister Sirin, was sent to the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 628 as a gift by Al-Muqawqis, a Christian governor of Alex ...

and Sirin. Maria became the concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

, with some sources reporting that she was later freed and married. The Muqawqis is reported in Islamic tradition as having presided over the contents of the parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins ...

and storing it in an ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

casket, although he did not convert to Islam.

Letter to Khosrau II of the Sassanid Kingdom

The letter to Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

( ar, كِسْرٰى, Kisrá) is translated by Muslim historians as:

According to Muslim tradition, the letter was sent through Abdullah as-SahmiBahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

, delivered it to the Khosrau.[al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 417] Upon reading it Khosrow II reportedly tore up the document, saying, "A pitiful slave among my subjects dares to write his name before mine"Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

, to dispatch two valiant men to identify, seize and bring this man from Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

(Muhammad) to him. When Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi told Muhammad how Khosrow had torn his letter to pieces, Muhammad is said to have stated, "May God ikewise tear apart his kingdom," while reacting to the Caesar's behavior saying, "May God preserve his kingdom."

Other letters

The Sassanid governors of Bahrain and Yamamah

Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence.

Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence. Munzir ibn Sawa al-Tamimi

Munzir ibn Sawa ( ar, ٱلْمُنْذِر ٱبْن سَاوَىٰ, al-Munzir-bn-Sāwá) was the governor of the Persian Sasanian Empire of historical Bahrain, the eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula opposite of Tihamah.

Munzir was a prominen ...

, the governor of Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

, was apparently an addressee, with a letter having been delivered to him through al-'Alaa al-Hadrami. Some subjects of the governor reportedly converted to Islam, whereas others did not.[al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 421—424] A similar letter was sent to Hauda bin Ali, the governor of Yamamah

Al-Yamama ( ar, اليَمامَة, al-Yamāma) is a historical region in the southeastern Najd in modern-day Saudi Arabia, or sometimes more specifically, the now-extinct ancient village of Jaww al-Yamamah, near al-Kharj, after which the rest ...

, who replied that he would only convert if he were given a position of authority within Muhammad's government, a proposition which Muhammad was unwilling to accept.

The Ghassanids

Letter of Muhammad to al-Ḥārith bin ʾAbī Shamir al-Ghassānī, who ruled Byzantine Syria (called by Arabs ''ash-Shām'' "north country, the Levant" in contrast to ''al-Yaman'' "south country, the Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and sha ...

") based in Bosra,Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

,Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

Arabs (comparable though superior in status to the Herodian dynasty

The Herodian dynasty was a royal dynasty of Idumaean (Edomite) descent, ruling the Herodian Kingdom of Judea and later the Herodian Tetrarchy as a vassal state of the Roman Empire. The Herodian dynasty began with Herod the Great, who assumed t ...

of Roman Palestine

Syria Palaestina (literally, "Palestinian Syria";Trevor Bryce, 2009, ''The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia''Roland de Vaux, 1978, ''The Early History of Israel'', Page 2: "After the revolt of Bar Cochba in 135 ...

):

Al-Ghassani reportedly reacted less than favourably to Muhammad's correspondence, viewing it as an insult.

The 'Azd

Jayfar and 'Abd, princes of the powerful ruling ' Azd tribe which ruled Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

in collaboration with Persian governance, were sons of the client king

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

Juland (frequently spelt Al Julandā based on the Perso-Arabic

The Persian alphabet ( fa, الفبای فارسی, Alefbâye Fârsi) is a writing system that is a version of the Arabic script used for the Persian language spoken in Iran (Western Persian) and Afghanistan (Dari Persian) since the 7th ce ...

pronunciation). They embraced Islam peacefully on 630 AD upon receiving the letter sent from Muhammad through 'Amr ibn al-'As

( ar, عمرو بن العاص السهمي; 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and was assigned import ...

. The 'Azd subsequently played a major role in the ensuant Islamic conquests. They were one of the five tribal contingents that settled in the newly founded garrison city of Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

at the head of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

; under their general al-Muhallab ibn Abu Sufrah and also took part in the conquest of Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plat ...

and Transoxania.[A. Abu Ezzah, The political situation in Eastern Arabia at the Advent of Islam" p. 55]

The letter reads as follows:

See also

*Muslim history

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

* Itmam al-hujjah

*Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

Notes

Citations

References

*

*

*

*

* al-Mubarakpuri, Saif-ur-Rahman (2002). ''al-Raheeq al-Makhtoom, "The Sealed Nectar"''. Islamic University of Medina. Riyadh: Darussalam publishers. .

*

* P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth

Clifford Edmund Bosworth FBA (29 December 1928 – 28 February 2015) was an English historian and Orientalist, specialising in Arabic and Iranian studies.

Life

Bosworth was born on 29 December 1928 in Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire (now ...

, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (Ed.), ''Encyclopaedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is an encyclopaedia of the academic discipline of Islamic studies published by Brill. It is considered to be the standard reference work in the field of Islamic studies. The first edition was published ...

Online''. Brill Academic Publishers

Brill Academic Publishers (known as E. J. Brill, Koninklijke Brill, Brill ()) is a Dutch international academic publisher founded in 1683 in Leiden, Netherlands. With offices in Leiden, Boston, Paderborn and Singapore, Brill today publishes ...

..

*

*

Further reading

* Al-Ismail, Tahia (1998). ''The Life of Muhammad: his life based on the earliest sources''. Ta-Ha publishers Ltd, United Kingdom. .

*

* {{cite book, author=Watt, M Montgomery, title=Muhammad at Medina, location=United Kingdom, publisher=Oxford University Press, year=1981, isbn=0-19-577307-1

External links

Muhammad Husayn Haykal: "The Life of Muhammad"; Online version

Letters sent by Muhammad

Life of Muhammad

Treaties of Muhammad

Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading

Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading  In early June 619, Muhammad set out from Mecca to travel to Ta'if in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of

In early June 619, Muhammad set out from Mecca to travel to Ta'if in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of  In the summer of 620 during the pilgrimage season, six men of the

In the summer of 620 during the pilgrimage season, six men of the  A letter was sent from Muhammad to the emperor of the

A letter was sent from Muhammad to the emperor of the  There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to Muqawqis. Some scholars such as Nöldeke consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value".Öhrnberg; Mukawkis. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Muslim historians, in contrast, generally affirm the historicity of the reports. The text of the letter (sent by Hatib bin Abu Balta'ah) according to Islamic tradition is translated as follows:

The Muqawqis responded by sending gifts to Muhammad, including two female slaves,

There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to Muqawqis. Some scholars such as Nöldeke consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value".Öhrnberg; Mukawkis. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Muslim historians, in contrast, generally affirm the historicity of the reports. The text of the letter (sent by Hatib bin Abu Balta'ah) according to Islamic tradition is translated as follows:

The Muqawqis responded by sending gifts to Muhammad, including two female slaves,  Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence.

Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence.