Muckraking on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the

''The New York Times'', April 10, 1985. The term is a reference to a character in

The muckrakers would become known for their investigative journalism, evolving from the eras of "personal journalism"—a term historians Emery and Emery used in ''The Press and America'' (6th ed.) to describe the 19th century newspapers that were steered by strong leaders with an editorial voice (p. 173)—and

The muckrakers would become known for their investigative journalism, evolving from the eras of "personal journalism"—a term historians Emery and Emery used in ''The Press and America'' (6th ed.) to describe the 19th century newspapers that were steered by strong leaders with an editorial voice (p. 173)—and

Magazines were the leading outlets for muckraking journalism. Samuel S. McClure and

Magazines were the leading outlets for muckraking journalism. Samuel S. McClure and

After President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901, he began to manage the press corps. To do so, he elevated his press secretary to cabinet status and initiated press conferences. The muckraking journalists who emerged around 1900, like Lincoln Steffens, were not as easy for Roosevelt to manage as the objective journalists, and the President gave Steffens access to the White House and interviews to steer stories his way.

Roosevelt used the press very effectively to promote discussion and support for his

After President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901, he began to manage the press corps. To do so, he elevated his press secretary to cabinet status and initiated press conferences. The muckraking journalists who emerged around 1900, like Lincoln Steffens, were not as easy for Roosevelt to manage as the objective journalists, and the President gave Steffens access to the White House and interviews to steer stories his way.

Roosevelt used the press very effectively to promote discussion and support for his

contents

* . * . * Lucas, Stephen E. "Theodore Roosevelt's 'the man with the muck‐rake': A reinterpretation." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 59#4 (1973): 452–462. * . * * . * . * .

Nellie Bly Online

{{Journalism footer Investigative journalism Types of journalism Political metaphors referring to people Journalism occupations Progressive Era in the United States

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publications. The modern term generally references investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years res ...

or watchdog journalism; investigative journalists in the US are occasionally called "muckrakers" informally.

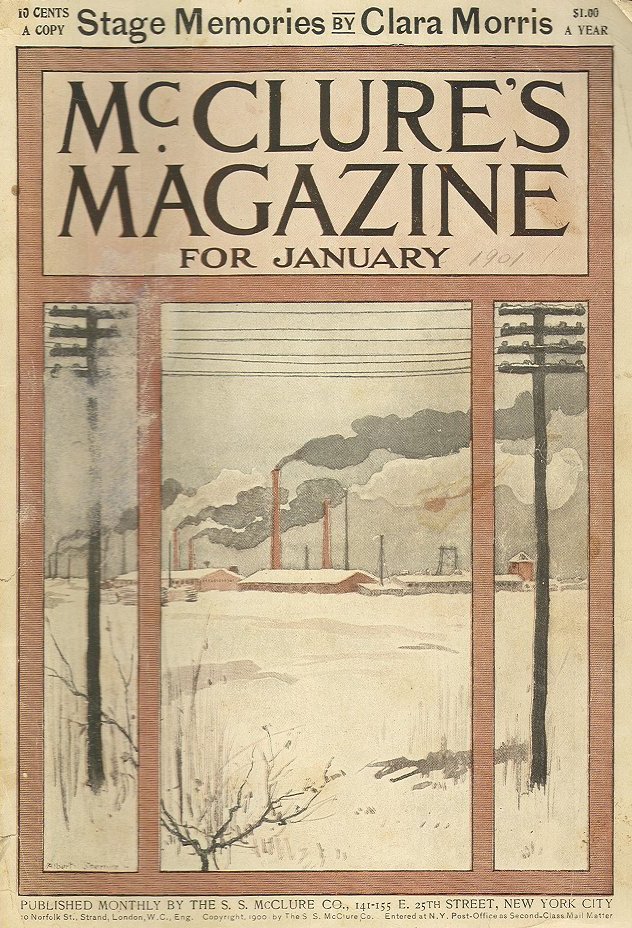

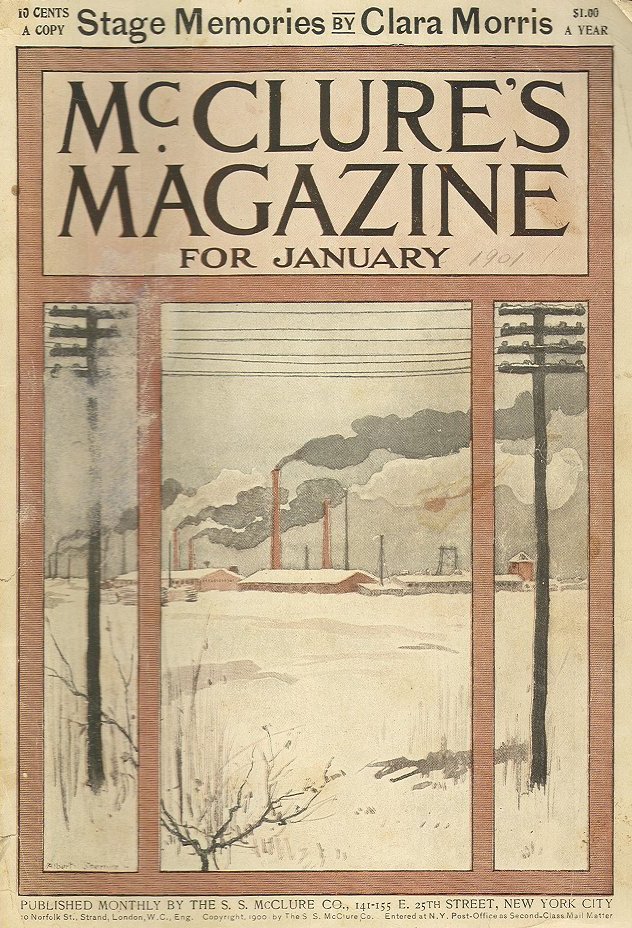

The muckrakers played a highly visible role during the Progressive Era. Muckraking magazines—notably ''McClure's

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wa ...

'' of the publisher S. S. McClure

Samuel Sidney McClure (February 17, 1857 – March 21, 1949) was an Irish-American publisher who became known as a key figure in investigative, or muckraking, journalism. He co-founded and ran ''McClure's Magazine'' from 1893 to 1911, which ran n ...

—took on corporate monopolies and political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership co ...

s, while trying to raise public awareness and anger at urban poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse

, unsafe working conditions, prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

, and child labor. Most of the muckrakers wrote nonfiction, but fictional exposés often had a major impact, too, such as those by Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

.

In contemporary American usage, the term can refer to journalists or others who "dig deep for the facts" or, when used pejoratively, those who seek to cause scandal."'Muckraker: 2 Meanings"''The New York Times'', April 10, 1985. The term is a reference to a character in

John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's classic ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'', "the Man with the Muck-rake", who rejected salvation to focus on filth. It became popular after President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

referred to the character in a 1906 speech; Roosevelt acknowledged that "the men with the muck rakes are often indispensable to the well being of society; but only if they know when to stop raking the muck."

History

While a literature of reform had already appeared by the mid-19th century, the kind of reporting that would come to be called "muckraking" began to appear around 1900. By the 1900s, magazines such as ''Collier's Weekly

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Colli ...

'', ''Munsey's Magazine

''Munsey's Weekly'', later known as ''Munsey's Magazine'', was a 36-page quarto American magazine founded by Frank A. Munsey in 1889 and edited by John Kendrick Bangs. Frank Munsey aimed to publish "a magazine of the people and for the people, w ...

'' and '' McClure's Magazine'' were already in wide circulation and read avidly by the growing middle class. The January 1903 issue of ''McClure's'' is considered to be the official beginning of muckraking journalism, although the muckrakers would get their label later. Ida M. Tarbell ("The History of Standard Oil"), Lincoln Steffens ("The Shame of the Cities") and Ray Stannard Baker ("The Right to Work"), simultaneously published famous works in that single issue. Claude H. Wetmore and Lincoln Steffens' previous article "Tweed Days in St. Louis" in ''McClure's'' October 1902 issue was called the first muckraking article.

Changes in journalism prior to 1903

The muckrakers would become known for their investigative journalism, evolving from the eras of "personal journalism"—a term historians Emery and Emery used in ''The Press and America'' (6th ed.) to describe the 19th century newspapers that were steered by strong leaders with an editorial voice (p. 173)—and

The muckrakers would become known for their investigative journalism, evolving from the eras of "personal journalism"—a term historians Emery and Emery used in ''The Press and America'' (6th ed.) to describe the 19th century newspapers that were steered by strong leaders with an editorial voice (p. 173)—and yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

.

One of the biggest urban scandals of the post-Civil War era was the corruption and bribery case of Tammany boss William M. Tweed

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany ...

in 1871 that was uncovered by newspapers. In his first muckraking article "Tweed Days in St. Louis", Lincoln Steffens exposed the graft, a system of political corruption, that was ingrained in St. Louis. While some muckrakers had already worked for reform newspapers of the personal journalism variety, such as Steffens who was a reporter for the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

'' under Edwin Lawrence Godkin

Edwin Lawrence Godkin (2 October 183121 May 1902) was an Irish-born American journalist and newspaper editor. He founded ''The Nation'' and was the editor-in-chief of the '' New York Evening Post'' from 1883 to 1899.Eric Fettman, "Godkin, E.L." ...

, other muckrakers had worked for yellow journals before moving on to magazines around 1900, such as Charles Edward Russell who was a journalist and editor of Joseph Pulitzer's ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

''. Publishers of yellow journals, such as Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, were more intent on increasing circulation through scandal, crime, entertainment and sensationalism.

Just as the muckrakers became well known for their crusades, journalists from the eras of "personal journalism" and "yellow journalism" had gained fame through their investigative articles, including articles that exposed wrongdoing. Note that in ''yellow journalism'', the idea was to stir up the public with sensationalism, and thus sell more papers. If, in the process, a social wrong was exposed that the average man could get indignant about, that was fine, but it was not the intent to correct social wrongs as it was with true investigative journalists and muckrakers.

Julius Chambers

Julius Chambers, F.R.G.S., (November 21, 1850 – February 12, 1920) was an American author, editor, journalist, travel writer, and activist against psychiatric abuse.

Life and works

Julius Chambers was born in Bellefontaine, Ohio on November ...

of the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' could be considered to be the original muckraker. Chambers undertook a journalistic investigation of Bloomingdale Asylum in 1872, having himself committed with the help of some of his friends and his newspaper's city editor. His intent was to obtain information about alleged abuse of inmates. When articles and accounts of the experience were published in the ''Tribune'', it led to the release of twelve patients who were not mentally ill, a reorganization of the staff and administration of the institution and, eventually, to a change in the lunacy laws. This later led to the publication of the book ''A Mad World and Its Inhabitants'' (1876). From this time onward, Chambers was frequently invited to speak on the rights of the mentally ill and the need for proper facilities for their accommodation, care and treatment.

Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochran Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist, industrialist, inventor, and charity worker who was widely known for her record-breaki ...

, another yellow journalist, used the undercover technique of investigation in reporting ''Ten Days in a Mad-House

''Ten Days in a Mad-House'' is a book by American journalist Nellie Bly. It was initially published as a series of articles for the '' New York World''. Bly later compiled the articles into a book, being published by Ian L. Munro in New York Cit ...

'', her 1887 exposé on patient abuse at Bellevue Mental Hospital, first published as a series of articles in ''The World

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

'' newspaper and then as a book. Nellie would go on to write more articles on corrupt politicians, sweat-shop working conditions and other societal injustices.

Other works that predate the muckrakers

*Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the United States government. She de ...

(1831–1885) –''A Century of Dishonor,'' U.S. policy regarding Native Americans.

* Henry Demarest Lloyd (1847–1903) – ''Wealth Against Commonwealth,'' exposed the corruption within the Standard Oil Company.

* Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) – an author of a series of articles concerning Jim Crow laws and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in 1884, and co-owned the newspaper ''The Free Speech'' in Memphis in which she began an anti-lynching campaign.

* Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

(1842–1913(?)) – author of a long-running series of articles published from 1883 through 1896 in ''The Wasp'' and the ''San Francisco Examiner'' attacking the Big Four and the Central Pacific Railroad for political corruption.

* B. O. Flower

Benjamin Orange Flower (October 19, 1858 – December 24, 1918), known most commonly by his initials "B.O.", was an American muckraking journalist of the Progressive era. Flower is best remembered as the editor of the liberal commentary magazin ...

(1858–1918) – author of articles in ''The Arena'' from 1889 through 1909 advocating for prison reform and prohibition of alcohol.

* Jacob Riis (1849–1914) – author of ''How the Other Half Lives'', advocating for changes to tenements through flash photography

The muckrakers appeared at a moment when journalism was undergoing changes in style and practice. In response to yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

, which had exaggerated facts, objective journalism, as exemplified by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' under Adolph Ochs

Adolph Simon Ochs (March 12, 1858 – April 8, 1935) was an American newspaper publisher and former owner of ''The New York Times'' and ''The Chattanooga Times'' (now the '' Chattanooga Times Free Press'').

Early life and career

Ochs was born ...

after 1896, turned away from sensationalism and reported facts with the intention of being impartial and a newspaper of record. The growth of wire services had also contributed to the spread of the objective reporting style. Muckraking publishers like Samuel S. McClure

Samuel Sidney McClure (February 17, 1857 – March 21, 1949) was an Irish-American publisher who became known as a key figure in investigative, or muckraking, journalism. He co-founded and ran ''McClure's Magazine'' from 1893 to 1911, which ran n ...

also emphasized factual reporting, but he also wanted what historian Michael Schudson

Michael S. Schudson

Michael S. Schudson (born November 3, 1946) is professor of journalism in the graduate school of journalism of Columbia University and adjunct professor in the department of sociology. He is professor emeritus at the Univers ...

had identified as one of the preferred qualities of journalism at the time, namely, the mixture of "reliability and sparkle" to interest a mass audience. In contrast with objective reporting, the journalists, whom Roosevelt dubbed "muckrakers", saw themselves primarily as reformers and were politically engaged. Journalists of the previous eras were not linked to a single political, populist movement as the muckrakers were associated with Progressive reforms. While the muckrakers continued the investigative exposures and sensational traditions of yellow journalism, they wrote to change society. Their work reached a mass audience as circulation figures of the magazines rose on account of visibility and public interest.

Magazines

Magazines were the leading outlets for muckraking journalism. Samuel S. McClure and

Magazines were the leading outlets for muckraking journalism. Samuel S. McClure and John Sanborn Phillips

John Sanborn Phillips (1861–1949) attended Knox College in Illinois, where he worked on the student newspaper and met S. S. McClure. In 1887 McClure hired him to manage the home office of the McClure Newspaper Syndicate (founded in 1884).

The ...

started ''McClure's Magazine'' in May 1893. McClure led the magazine industry by cutting the price of an issue to 15 cents, attracting advertisers, giving audiences illustrations and well-written content and then raising ad rates after increased sales, with ''Munsey's'' and ''Cosmopolitan'' following suit.

McClure sought out and hired talented writers, like the then unknown Ida M. Tarbell or the seasoned journalist and editor Lincoln Steffens. The magazine's pool of writers were associated with the muckraker movement, such as Ray Stannard Baker, Burton J. Hendrick

Burton Jesse Hendrick (December 8, 1870 – March 23, 1949), born in New Haven, Connecticut, was an American author. While attending Yale University, Hendrick was editor of both The Yale Courant and The Yale Literary Magazine. He received his BA ...

, George Kennan (explorer)

George Kennan (February 16, 1845 – May 10, 1924) was an American explorer noted for his travels in the Kamchatka and Caucasus regions of the Russian Empire. He was a cousin twice removed of the American diplomat and historian George F. K ...

, John Moody (financial analyst), Henry Reuterdahl

Henry Reuterdahl (August 12, 1870 – December 21, 1925) was a Swedish-American painter highly acclaimed for his nautical artwork. He had a long relationship with the United States Navy.

In addition to serving as a Lieutenant Commander in the ...

, George Kibbe Turner

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

, and Judson C. Welliver

Judson Churchill Welliver (August 13, 1870 – April 14, 1943) was a "literary clerk" to President Warren G. Harding and is usually credited as being the first presidential speechwriter.

Biography

Judson Welliver was born on August 13, 1870 in ...

, and their names adorned the front covers. The other magazines associated with muckraking journalism were ''American Magazine'' (Lincoln Steffens), ''Arena'' (G. W. Galvin

G is the seventh letter of the Latin alphabet.

G may also refer to:

Places

* Gabon, international license plate code G

* Glasgow, UK postal code G

* Eastern Quebec, Canadian postal prefix G

* Melbourne Cricket Ground in Melbourne, Australia, ...

and John Moody), ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Coll ...

Weekly'' (Samuel Hopkins Adams

Samuel Hopkins Adams (January 26, 1871 – November 16, 1958) was an American writer who was an investigative journalist and muckraker.

Background

Adams was born in Dunkirk, New York. Adams was a muckraker, known for exposing public-health in ...

, C.P. Connolly

Christopher Patrick Connolly (1863–1935), better known as C.P. Connolly, was an American investigative journalist who was associated for many years with ''Collier's Weekly'' and the muckrakers.

Connolly was a former Montana prosecutor. He is ...

, L. R. Glavis

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

, Will Irwin

William Henry Irwin (September 14, 1873 – February 24, 1948) was an American author, writer and journalist who was associated with the muckrakers.

Early life

Irwin was born in 1873 in Oneida, New York. In his early childhood, the Irwin fam ...

, J. M. Oskison, Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

), ''Cosmopolitan'' (Josiah Flynt

Josiah Flynt (properly Josiah Flynt Willard) (January 23, 1869 – January 20, 1907) was an American sociologist and author.

Biography

Flynt was born in Appleton, Wisconsin, to Oliver and Mary Bannister Willard. His father was editor of the l ...

, Alfred Henry Lewis, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, Charles P. Norcross

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

, Charles Edward Russell), ''Everybody's Magazine'' (William Hard

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, Thomas William Lawson, Benjamin B. Lindsey

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...

, Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of Sa ...

, David Graham Phillips, Charles Edward Russell, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Merrill A. Teague Merrill may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Merrill Field, Anchorage, Alaska

* Merrill, Iowa

*Merrill, Maine

* Merrill, Michigan

*Merrill, Mississippi, an unincorporated community near Lucedale in George County

* Merrill, Oregon

* Merrill, ...

, Bessie and Marie Van Vorst

Marie Louise Van Vorst (November 23, 1867 – December 16, 1936) was an American writer, researcher, painter, and volunteer nurse during World War I.

Early life

Marie Louise Van Vorst was born in New York City, the daughter of Hooper Cumming ...

), ''Hampton's'' (Rheta Childe Dorr

Rheta Louise Childe Dorr (1868–1948) was an American journalist, suffragist newspaper editor, writer, and political activist. Dorr is best remembered as one of the leading female muckraking journalists of the Progressive era and as the first ...

, Benjamin B. Hampton

Benjamin Bowles Hampton (1875–1932) was an American film producer, writer, and director. He led a 1916 plan to conglomerate film companies via acquisition. He was married to actress Claire Adams and was a partner in Zane Grey Pictures. He wrot ...

, John L. Mathews

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, Charles Edward Russell, and Judson C. Welliver), ''The Independent'' ( George Walbridge Perkins, Sr.), ''Outlook'' (William Hard), '' Pearson's Magazine'' (Alfred Henry Lewis, Charles Edward Russell), ''Twentieth Century'' (George French), and ''World's Work'' ( C.M. Keys and Q.P.). Other titles of interest include ''Chatauquan'', ''Dial'', ''St. Nicholas''. In addition, Theodore Roosevelt wrote for '' Scribner's Magazine'' after leaving office.

Origin of the term, Theodore Roosevelt

After President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901, he began to manage the press corps. To do so, he elevated his press secretary to cabinet status and initiated press conferences. The muckraking journalists who emerged around 1900, like Lincoln Steffens, were not as easy for Roosevelt to manage as the objective journalists, and the President gave Steffens access to the White House and interviews to steer stories his way.

Roosevelt used the press very effectively to promote discussion and support for his

After President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901, he began to manage the press corps. To do so, he elevated his press secretary to cabinet status and initiated press conferences. The muckraking journalists who emerged around 1900, like Lincoln Steffens, were not as easy for Roosevelt to manage as the objective journalists, and the President gave Steffens access to the White House and interviews to steer stories his way.

Roosevelt used the press very effectively to promote discussion and support for his Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

policies among his base in the middle-class electorate. When journalists went after different topics, he complained about their wallowing in the mud. In a speech on April 14, 1906 on the occasion of dedicating the House of Representatives office building, he drew on a character from John Bunyan's 1678 classic, ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'', saying:

While cautioning about possible pitfalls of keeping one's attention ever trained downward, "on the muck", Roosevelt emphasized the social benefit of investigative muckraking reporting, saying:

Most of these journalists detested being called muckrakers. They felt betrayed that Roosevelt would describe them with such a term after they had helped him with his election. Muckraker David Graham Philips believed that the tag of muckraker brought about the end of the movement as it was easier to group and attack the journalists.

The term eventually came to be used in reference to investigative journalists who reported about and exposed such issues as crime, fraud, waste, public health and safety, graft, and illegal financial practices. A muckraker's reporting may span businesses and government.

Early 20th century muckraking

Some of the key documents that came to define the work of the muckrakers were: Ray Stannard Baker published "The Right to Work" in ''McClure's Magazine'' in 1903, about coal mine conditions, a coal strike, and the situation of non-striking workers (or scabs). Many of the non-striking workers had no special training or knowledge in mining, since they were simply farmers looking for work. His investigative work portrayed the dangerous conditions in which these people worked in the mines, and the dangers they faced from union members who did not want them to work. Lincoln Steffens published "Tweed Days in St. Louis", in which he profiled corrupt leaders in St. Louis, in October 1902, in ''McClure's Magazine''. The prominence of the article helped lawyer Joseph Folk to lead an investigation of the corrupt political ring in St. Louis. Ida Tarbell published ''The Rise of the Standard Oil Company'' in 1902, providing insight into the manipulation of trusts. One trust they manipulated was with Christopher Dunn Co. She followed that work with '' The History of The Standard Oil Company: the Oil War of 1872'', which appeared in ''McClure's Magazine'' in 1908. She condemned Rockefeller's immoral and ruthless business tactics and emphasized "our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises." Her book generated enough public anger that it led to the splitting up of Standard Oil under the Sherman Anti Trust Act.Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

published ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' in 1906, which revealed conditions in the meat packing industry in the United States and was a major factor in the establishment of the Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

and Meat Inspection Act. Sinclair wrote the book with the intent of addressing unsafe working conditions in that industry, not food safety. Sinclair was not a professional journalist but his story was first serialized before being published in book form. Sinclair considered himself to be a muckraker.

" The Treason of the Senate: Aldrich, the Head of it All", by David Graham Phillips, published as a series of articles in ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' magazine in February 1906, described corruption in the U.S. Senate. This work was a keystone in the creation of the Seventeenth Amendment which established the election of Senators through popular vote.

'' The Great American Fraud'' (1905) by Samuel Hopkins Adams

Samuel Hopkins Adams (January 26, 1871 – November 16, 1958) was an American writer who was an investigative journalist and muckraker.

Background

Adams was born in Dunkirk, New York. Adams was a muckraker, known for exposing public-health in ...

revealed fraudulent claims and endorsements of patent medicines in America. This article shed light on the many false claims that pharmaceutical companies and other manufacturers would make as to the potency of their medicines, drugs and tonics. This exposure contributed heavily to the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

alongside Upton Sinclair's work. Using the example of Peruna in his article, Adams described how this tonic, which was made of seven compound drugs and alcohol, did not have "any great potency". Manufacturers sold it at an obscene price and hence made immense profits. His work forced a crackdown on a number of other patents and fraudulent schemes of medicinal companies.

Many other works by muckrakers brought to light a variety of issues in America during the Progressive era. These writers focused on a wide range of issues including the monopoly of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

; cattle processing and meat packing

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is gener ...

; patent medicines; child labor; and wages, labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

, and working conditions in industry and agriculture. In a number of instances, the revelations of muckraking journalists led to public outcry, governmental and legal investigations, and, in some cases, legislation was enacted to address the issues the writers identified, such as harmful social conditions; pollution; food and product safety standards; sexual harassment; unfair labor practices; fraud; and other matters. The work of the muckrakers in the early years, and those today, span a wide array of legal, social, ethical and public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public ...

concerns.

Muckrakers and their works

*Samuel Hopkins Adams

Samuel Hopkins Adams (January 26, 1871 – November 16, 1958) was an American writer who was an investigative journalist and muckraker.

Background

Adams was born in Dunkirk, New York. Adams was a muckraker, known for exposing public-health in ...

(1871–1958) – ''The Great American Fraud'' (1905), exposed false claims about patent medicines.

* Paul Y. Anderson

Paul Y. Anderson (August 29, 1893 – December 6, 1938) was an American journalist. He was a pioneering muckraker and played a role in exposing the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s. His coverage included the 1917 race riots in East St. Louis and t ...

(August 29, 1893 – December 6, 1938) is best known for his reporting of a race riot and the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomi ...

.

* Ray Stannard Baker (1870–1946) – of ''McClure's

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wa ...

'' & '' The American Magazine''.

* Louis D. Brandeis (1856–1941) – published his combined findings of the monopolies of big banks and big business in his 1914 book ''Other People's Money And How the Bankers Use It

''Other People's Money And How the Bankers Use It'' (1914) is a collection of essays written by Louis Brandeis first published as a book in 1914, and reissued in 1933. This book is critical of banks and insurance companies.

Contents

All the chap ...

''. Subsequently appointed to the Supreme Court (1916).

* Marion Hamilton Carter

Marion Hamilton Carter (1865-1937) was an American Progressive Era educator, psychologist, children’s literature editor, short story writer, and artist. In her prime, she worked as a muckraker journalist, magazine editor, women’s suffrage ad ...

(1865-1937) - "Pellagra" and "The Vampire of the South" 1909 ''McClure's

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wa ...

''.

* Burton J. Hendrick

Burton Jesse Hendrick (December 8, 1870 – March 23, 1949), born in New Haven, Connecticut, was an American author. While attending Yale University, Hendrick was editor of both The Yale Courant and The Yale Literary Magazine. He received his BA ...

(1870–1949) – "The Story of Life Insurance" May – November 1906 ''McClure's

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wa ...

''.

* Frances Kellor (1873–1952) – studied chronic unemployment in her book ''Out of Work'' (1904).

* Thomas William Lawson (1857–1924) ''Frenzied Finance'' (1906) on Amalgamated Copper stock scandal.

* Edwin Markham

Edwin Markham (born Charles Edward Anson Markham; April 23, 1852 – March 7, 1940) was an American poet. From 1923 to 1931 he was Poet Laureate of Oregon.

Life

Edwin Markham was born in Oregon City, Oregon, and was the youngest of 10 children ...

(1852–1940) – published an exposé of child labor in ''Children in Bondage'' (1914).

* Gustavus Myers

Gustavus Myers (1872–1942) was an American journalist and historian who published a series of highly critical and influential studies on the social costs of wealth accumulation. His name has been associated with the muckraking era of US litera ...

(1872–1942) – documented corruption in his first book "The History of Tammany Hall" (1901) unpublished, Revised edition, Boni and Liveright, 1917. His second book (in three volumes) related a "History of the Great American Fortunes" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1909–10; Single volume Modern Library edition, New York, 1936. Other works include "History of The Supreme Court of the United States" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1912. "A History of Canadian Wealth" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1914. "History of Bigotry in the United States" New York: Random House, 1943 Published posthumously.

* Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of Sa ...

(1870–1902) '' The Octopus''.

* Fremont Older

Fremont Older (August 30, 1856 – March 3, 1935) was a newspaperman and editor in San Francisco, California for nearly 50 years. He is best known for his campaigns against civic corruption, capital punishment, prison reform, and efforts on ...

(1856–1935) – wrote on San Francisco corruption and on the case of Tom Mooney.

* Drew Pearson (1897–1969) – wrote syndicated newspaper column "Washington Merry-Go-Round".

* Jacob Riis (1849–1914) – ''How the Other Half Lives

''How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York'' (1890) is an early publication of photojournalism by Jacob Riis, documenting squalid living conditions in New York City slums in the 1880s. The photographs served as a basis ...

,'' the slums.

* Charles Edward Russell (1860–1941) – investigated Beef Trust, Georgia's prison.

* Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

(1878–1968) – ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' (1906), US meat-packing industry, and the books in the "Dead Hand" series that critique the institutions (journalism, education, etc.) that could but did not prevent these abuses.

* John Spargo (1876–1966) – American reformer and author, ''The Bitter Cry of Children

''The Bitter Cry of Children'' is a book by socialist writer John Spargo, a muckraker and investigative journalist

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as seri ...

'' (child labor).

* Lincoln Steffens (1866–1936) ''The Shame of the Cities

''The Shame of the Cities'' is a book written by American author Lincoln Steffens. Published in 1904, it is a collection of articles which Steffens had written for ''McClure’s Magazine''. It reports on the workings of corrupt political machines ...

'' (1904) – uncovered the corruption of several political machines in major cities.

* Ida M. Tarbell (1857–1944) exposé, ''The History of the Standard Oil Company

''The History of the Standard Oil Company'' is a 1904 book by journalist Ida Tarbell. It is an exposé about the Standard Oil Company, run at the time by oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, the richest figure in American history. Originally serializ ...

''.

* John Kenneth Turner

John Kenneth Turner (April 5, 1879 – July 31, 1948) was an American publisher, journalist, and author. His book ''Barbarous Mexico'' helped discredit Mexican President Porfirio Díaz's regime in the eyes of the American public.

Early lif ...

(1879–1948) – author of ''Barbarous Mexico'' (1910), an account of the exploitative debt-peonage system used in Mexico under Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

.

* Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) – ''The Free Speech'' (1892) condemned the flaws in the United States justice system that allowed lynching to happen.

Disappearance

The influence of the muckrakers began to fade during the more conservative presidency ofWilliam Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. Corporations and political leaders were also more successful in silencing these journalists as advertiser boycotts forced some magazines to go bankrupt. Through their exposés, the nation was changed by reforms in cities, business, politics, and more. Monopolies such as Standard Oil were broken up and political machines fell apart; the problems uncovered by muckrakers were resolved and thus the muckrakers of that era were needed no longer.

Impact

According to Fred J. Cook, the muckrakers' journalism resulted in litigation or legislation that had a lasting impact, such as the end ofStandard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

's monopoly over the oil industry, the establishment of the Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

of 1906, the creation of the first child labor laws in the United States

Child labor laws in the United States address issues related to the employment and welfare of working children in the United States. The most sweeping federal law that restricts the employment and abuse of child workers is the Fair Labor Standard ...

around 1916. Their reports exposed bribery and corruption at the city and state level, as well as in Congress, that led to reforms and changes in election results.

"The effect on the soul of the nation was profound. It can hardly be considered an accident that the heyday of the muckrakers coincided with one of America's most yeasty and vigorous periods of ferment. The people of the country were aroused by the corruptions and wrongs of the age – and it was the muckrakers who informed and aroused them. The results showed in the great wave of progressivism and reform cresting in the remarkable spate of legislation that marked the first administration of Woodrow Wilson from 1913 to 1917. For this, the muckrakers had paved the way."

Other changes that resulted from muckraker articles include the reorganization of the U.S. Navy (after Henry Reuterdahl published a controversial article in McClure's). Muckraking investigations were used to change the way senators were elected by the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and led to government agencies to take on watchdog functions.

Since 1945

Some today use "investigative journalism" as a synonym for muckraking. Carey McWilliams, editor of the ''Nation'', assumed in 1970 that investigative journalism, and reform journalism, or muckraking, were the same type of journalism. Journalism textbooks point out that McClure's muckraking standards "Have become integral to the character of modern investigative journalism." Furthermore, the successes of the early muckrakers have continued to inspire journalists.Stephen Hess, ''Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters, 1978–2012'' (2012) Moreover, muckraking has become an integral part of journalism in American history. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein exposed the workings of the Nixon Administration inWatergate

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continu ...

, which led to Nixon's resignation. More recently, Edward Snowden

Edward Joseph Snowden (born June 21, 1983) is an American and naturalized Russian former computer intelligence consultant who leaked highly classified information from the National Security Agency (NSA) in 2013, when he was an employee and su ...

disclosed the activities of governmental spying, albeit illegally, which gave the public knowledge of the extent of the infringements on their privacy.

See also

* Child labor in the United States *History of American newspapers

The history of American newspapers begins in the early 18th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. American newspapers began as modest affairs—a sideline for printers. They became a political force in the campaign fo ...

* Whistleblower

A whistleblower (also written as whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person, often an employee, who reveals information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe or fraudulent. Whi ...

References

Bibliography

* Applegate, Edd. ''Muckrakers: A Biographical Dictionary of Writers and Editors'' (Scarecrow Press, 2008); 50 entries, mostly Americacontents

* . * . * Lucas, Stephen E. "Theodore Roosevelt's 'the man with the muck‐rake': A reinterpretation." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 59#4 (1973): 452–462. * . * * . * . * .

External links

* *Original Nellie Bly articles aNellie Bly Online

{{Journalism footer Investigative journalism Types of journalism Political metaphors referring to people Journalism occupations Progressive Era in the United States