Morisco revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former

''The Assimilation of Spain's Moriscos: Fiction or Reality?''

. Journal of Levantine Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, Winter 2011, pp. 11-30 The large majority of those permanently expelled settled on the western fringe of the Ottoman Empire and the

The

The

Islam has been present in Spain since the

Islam has been present in Spain since the

At the instigation of the

At the instigation of the  Although many Moriscos were sincere Christians, adult Moriscos were often assumed to be covert Muslims (i.e.

Although many Moriscos were sincere Christians, adult Moriscos were often assumed to be covert Muslims (i.e.

p. 281 In 1576, the Ottomans planned to send a three-pronged fleet from

One of the earliest re-examinations of Morisco expulsion was carried out by Trevor J. Dadson in 2007, devoting a significant section to the expulsion in Villarrubia de los Ojos in southern Castille. Villarubia's entire Morisco population were the target of three expulsions which they managed to avoid or from which they succeeded in returning from to their town of origin, being protected and hidden by their non-Morisco neighbours. Dadson provides numerous examples, of similar incidents throughout Spain whereby Moriscos were protected and supported by non-Moriscos and returned en masse from North Africa, Portugal or France to their towns of origin.

A similar study on the expulsion in Andalusia concluded it was an inefficient operation which was significantly reduced in its severity by resistance to the measure among local authorities and populations. It further highlights the constant flow of returnees from North Africa, creating a dilemma for the local inquisition who did not know how to deal with those who had been given no choice but to convert to Islam during their stay in Muslim lands as a result of the Royal Decree. Upon the coronation of Philip IV, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on returnees and in September 1628 the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion."

An investigation published in 2012 sheds light on the thousands of Moriscos who remained in the province of Granada alone, surviving both the initial expulsion to other parts of Spain in 1571 and the final expulsion of 1604. These Moriscos managed to evade in various ways the royal decrees, hiding their true origin thereafter. More surprisingly, by the 17th and 18th centuries much of this group accumulated great wealth by controlling the silk trade and also holding about a hundred public offices. Most of these lineages were nevertheless completely assimilated over generations despite their endogamic practices. A compact core of active crypto-Muslims was prosecuted by the Inquisition in 1727, receiving comparatively light sentences. These convicts kept alive their identity until the late 18th century.

The attempted expulsion of Moriscos from

One of the earliest re-examinations of Morisco expulsion was carried out by Trevor J. Dadson in 2007, devoting a significant section to the expulsion in Villarrubia de los Ojos in southern Castille. Villarubia's entire Morisco population were the target of three expulsions which they managed to avoid or from which they succeeded in returning from to their town of origin, being protected and hidden by their non-Morisco neighbours. Dadson provides numerous examples, of similar incidents throughout Spain whereby Moriscos were protected and supported by non-Moriscos and returned en masse from North Africa, Portugal or France to their towns of origin.

A similar study on the expulsion in Andalusia concluded it was an inefficient operation which was significantly reduced in its severity by resistance to the measure among local authorities and populations. It further highlights the constant flow of returnees from North Africa, creating a dilemma for the local inquisition who did not know how to deal with those who had been given no choice but to convert to Islam during their stay in Muslim lands as a result of the Royal Decree. Upon the coronation of Philip IV, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on returnees and in September 1628 the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion."

An investigation published in 2012 sheds light on the thousands of Moriscos who remained in the province of Granada alone, surviving both the initial expulsion to other parts of Spain in 1571 and the final expulsion of 1604. These Moriscos managed to evade in various ways the royal decrees, hiding their true origin thereafter. More surprisingly, by the 17th and 18th centuries much of this group accumulated great wealth by controlling the silk trade and also holding about a hundred public offices. Most of these lineages were nevertheless completely assimilated over generations despite their endogamic practices. A compact core of active crypto-Muslims was prosecuted by the Inquisition in 1727, receiving comparatively light sentences. These convicts kept alive their identity until the late 18th century.

The attempted expulsion of Moriscos from  Recent genetic studies of North African admixture among modern-day Spaniards have found high levels of North African (Berber) and Sub-Saharan African admixture among Spanish and Portuguese populations as compared to the rest of southern and western Europe, and such admixture does not follow a North-South gradient as one would initially expect, but more of an East-West one.

While the descendants of those Moriscos who fled to North Africa have remained strongly aware and proud of their Andalusi roots, the Moriscos' identity as a community was wiped out in Spain, be it via either expulsion or absorption by the dominant culture. Nevertheless, a journalistic investigation over the past years has uncovered existing communities in rural Spain (more specifically in the provinces of

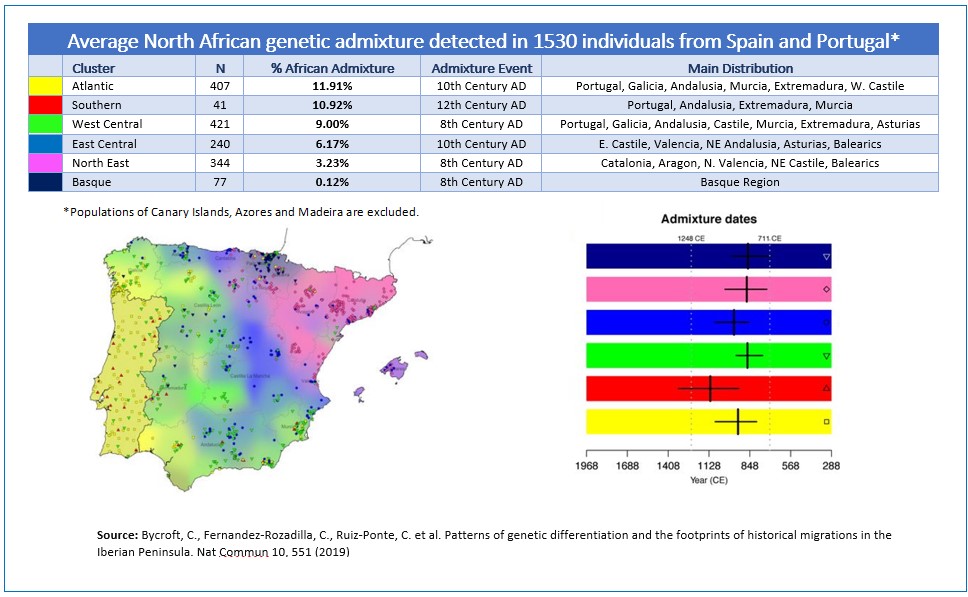

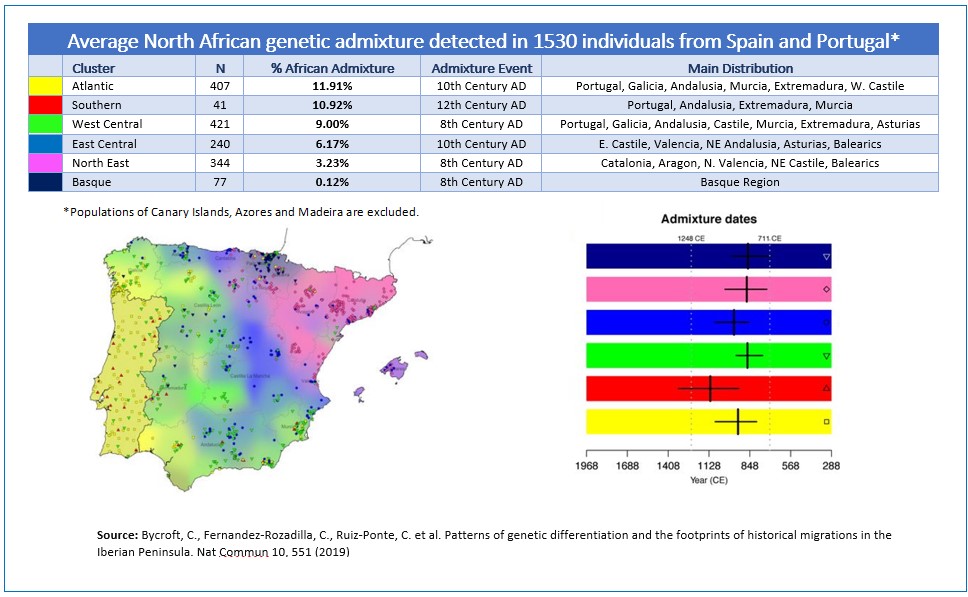

Recent genetic studies of North African admixture among modern-day Spaniards have found high levels of North African (Berber) and Sub-Saharan African admixture among Spanish and Portuguese populations as compared to the rest of southern and western Europe, and such admixture does not follow a North-South gradient as one would initially expect, but more of an East-West one.

While the descendants of those Moriscos who fled to North Africa have remained strongly aware and proud of their Andalusi roots, the Moriscos' identity as a community was wiped out in Spain, be it via either expulsion or absorption by the dominant culture. Nevertheless, a journalistic investigation over the past years has uncovered existing communities in rural Spain (more specifically in the provinces of

chapter 3

Javier García-Egocheaga Vergara, , Tikal Ediciones (Ed. Susaeta), Madrid, 2003.

Spain's Morisco population was the last population who self-identified and traced its roots to the various waves of Muslim conquerors from North Africa. Historians generally agree that, at the height of Muslim rule, Muladis or Muslims of pre-Islamic Iberian origin were likely to constitute the large majority of Muslims in Spain.

Studies in population genetics which aim to ascertain Morisco ancestry in modern populations search for Iberian or European genetic markers among contemporary Morisco descendants in North Africa, and for North African genetic markers among modern day Spaniards.

A wide number of recent genetic studies of modern-day Spanish and Portuguese populations have ascertained significantly higher levels of North African admixture in the Iberian peninsula than in the rest of the European continent. which is generally attributed to Islamic rule and settlement of the Iberian peninsula. Common North African genetic markers which are relatively high frequencies in the Iberian peninsula as compared to the rest of the European continent are Y-chromosome E1b1b1b1(E-M81)

* and Macro-haplogroup L (mtDNA) and U6. Studies coincide that North African admixture tends to increase in the South and West of the peninsula, peaking in parts of Andalusia, Extremadura, Southern Portugal and Western Castile. Distribution of North African markers are largely absent from the northeast of Spain as well as the Basque country. The uneven distribution of admixture in Spain has been explained by the extent and intensity of Islamic colonization in a given area, but also by the varying levels of success in attempting to expel the Moriscos in different regions of Spain}, as well as forced and voluntary Morisco population movements during the 16th and 17th centuries.

As for tracing Morisco descendants in North Africa, to date there have been few genetic studies of populations of Morisco origin in the Maghreb region, although studies of the Moroccan population have not detected significant recent genetic inflow from the Iberian peninsula. A recent study of various Tunisian ethnic groups has found that all were indigenous North African, including those who self-identified as Andalusians.

Spain's Morisco population was the last population who self-identified and traced its roots to the various waves of Muslim conquerors from North Africa. Historians generally agree that, at the height of Muslim rule, Muladis or Muslims of pre-Islamic Iberian origin were likely to constitute the large majority of Muslims in Spain.

Studies in population genetics which aim to ascertain Morisco ancestry in modern populations search for Iberian or European genetic markers among contemporary Morisco descendants in North Africa, and for North African genetic markers among modern day Spaniards.

A wide number of recent genetic studies of modern-day Spanish and Portuguese populations have ascertained significantly higher levels of North African admixture in the Iberian peninsula than in the rest of the European continent. which is generally attributed to Islamic rule and settlement of the Iberian peninsula. Common North African genetic markers which are relatively high frequencies in the Iberian peninsula as compared to the rest of the European continent are Y-chromosome E1b1b1b1(E-M81)

* and Macro-haplogroup L (mtDNA) and U6. Studies coincide that North African admixture tends to increase in the South and West of the peninsula, peaking in parts of Andalusia, Extremadura, Southern Portugal and Western Castile. Distribution of North African markers are largely absent from the northeast of Spain as well as the Basque country. The uneven distribution of admixture in Spain has been explained by the extent and intensity of Islamic colonization in a given area, but also by the varying levels of success in attempting to expel the Moriscos in different regions of Spain}, as well as forced and voluntary Morisco population movements during the 16th and 17th centuries.

As for tracing Morisco descendants in North Africa, to date there have been few genetic studies of populations of Morisco origin in the Maghreb region, although studies of the Moroccan population have not detected significant recent genetic inflow from the Iberian peninsula. A recent study of various Tunisian ethnic groups has found that all were indigenous North African, including those who self-identified as Andalusians.

In colonial Spanish America the term ''Morisco'' had two meanings. One was for Spanish immigrants to Spanish America who had been Moriscos passing for Christian, since Moriscos as well as "New Christian" converted Jews were banned in the late sixteenth century from immigrating there. One such case in colonial Colombia where a man was accused of being a Morisco, the court examined his penis to determine if he were circumcised in the Islamic (and Jewish) manner.

The more common usage of Morisco in Spanish America was for light-skinned offspring of a Spaniard and a

In colonial Spanish America the term ''Morisco'' had two meanings. One was for Spanish immigrants to Spanish America who had been Moriscos passing for Christian, since Moriscos as well as "New Christian" converted Jews were banned in the late sixteenth century from immigrating there. One such case in colonial Colombia where a man was accused of being a Morisco, the court examined his penis to determine if he were circumcised in the Islamic (and Jewish) manner.

The more common usage of Morisco in Spanish America was for light-skinned offspring of a Spaniard and a

''Expulsion of the Muslims from Spain''EGO - European History Online

Mainz

Institute of European History

2020, retrieved: March 17, 2021

pdf

. * * Casey. James."Moriscos and the Depopulation of Valencia" ''Past & Present'' No. 50 (Feb., 1971), pp. 19–4

online

* * Chejne, Anwar G. ''Islam and the West, the Moriscos: A Cultural and Social History'' (1983) * * . Individual chapters: :* * * * Hess, Andrew C. "The Moriscos: An Ottoman Fifth Column in Sixteenth-Century Spain." ''American Historical Review'' 74#1 (1968): 1-25.

online

* Jónsson, Már. "The expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain in 1609–1614: the destruction of an Islamic periphery." ''Journal of Global History'' 2.2 (2007): 195-212. * * * Perry, Mary Elizabeth. ''The Handless Maiden: Moriscos and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern Spain'', Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 2005. * Phillips, Carla Rahn. "The Moriscos of La Mancha, 1570-1614." ''The Journal of Modern History'' 50.S2 (1978): D1067-D1095

online

* * Wiegers, Gerard A. ''Islamic Literature in Spanish and Aljamiado: Iça of Segovia (fl. 1450), His antecedents and Successors''. Leiden: Brill, 1994. * Wiegers, Gerard A. "Managing Disaster: Networks of the Moriscos during the Process of the Expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula around 1609." ''Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures'' 36.2 (2010): 141-168.

Alhadith, a web resource at Stanford University for students and scholars of Morisco language and culture

*

The expulsion of Muslims from Spain by Professor Roger Boase

* ttps://archive.org/stream/moriscosofspaint00leahuoft#page/n3/mode/2up ´The Moriscos of Spain, their conversion and expulsion´ by Lea, Henry Charles {{Authority control Crypto-Islam Spanish Inquisition Portuguese Inquisition

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

commanded to convert to Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person to Christianity. Different Christian denominations may perform various different kinds of rituals or ceremonies initiation into their community of believe ...

or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open practice of Islam by its sizeable Muslim population (termed ''mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for M ...

'') in the early 16th century.

The Unified Portuguese and Spanish monarchs mistrusted Moriscos and feared that they would prompt new invasions from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

after the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

. So between 1609 and 1614 they began to expel them systematically from the various kingdoms of the united realm. The most severe expulsions occurred in the eastern Kingdom of Valencia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

. The exact number of Moriscos present in Spain prior to expulsion is unknown and can only be guessed on the basis of official records of the edict of expulsion. Furthermore, the overall success of the expulsion is subject to academic debate, with estimates on the proportion of those who avoided expulsion or returned to Spain ranging from 5% to 40%.Trevor J. Dadson''The Assimilation of Spain's Moriscos: Fiction or Reality?''

. Journal of Levantine Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, Winter 2011, pp. 11-30 The large majority of those permanently expelled settled on the western fringe of the Ottoman Empire and the

Kingdom of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

. The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences.

In Spanish, ''morisco'' was also used in official colonial-era documentation in Spanish America to denote mixed-race ''casta

() is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas it also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical f ...

s'': the children of relations between Spanish men and women of mixed African-European ancestry.

Name and etymology

The label ''morisco'' for Muslims who converted to Christianity began to appear in texts in the first half of the sixteenth century, though use of the term at this time was limited. Usage became widespread in Christian sources during the second half of the century, but it was unclear whether Moriscos adopted the term. In their texts, it was more common for them to speak of themselves simply as ''muslimes'' (Muslims); in later periods, they may have begun to accept the label. In modern times, the label is in widespread use in Spanish literature and adopted by other languages, includingModern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA), terms used mostly by linguists, is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; occasionally, it also re ...

(in which it appears as ''al-Mūrīskiyyūn / al-Mōrīskiyyūn'' ( ar, الموريسكيون)).

The word ''morisco'' appears in twelfth-century Castilian texts as an adjective for the noun ''moro''. These two words are comparable to the English adjective "Moorish" and noun " Moor". Mediaeval Castilians used the words in the general senses of "Muslim" or an "Arabic-speaker" as in the case of Muslim converts; the words continued to be used in these older meanings even after the more specific meaning of ''morisco'' (which does not have a corresponding noun) became widespread.

According to L. P. Harvey

Leonard Patrick Harvey (often credited L. P. Harvey, 25 February 1929-4 August 2018) held lectureships in Spanish at Oxford University (1956–58), Southampton (1958–60), and Queen Mary College, London (1960–63), was Head of the Spanish Depa ...

, the two different meanings of the word ''morisco'' have resulted in mistakes when modern scholars misread historical text containing ''morisco'' in the older meaning, as having the newer meaning. In the early years after the forced conversions, the Christians used the terms "new Christians", "new converts", or the longer "new Christians, converted from Moors" (''nuevos christianos convertidos de moros''; to distinguish from those converted from Judaism) to refer to this group.

In 1517, the word ''morisco'' became a "category" added to the array of cultural and religious identities that existed at the time, used to identify Muslim converts to Christianity in Granada and Castille. The term was a pejorative adaptation of the adjective ''morisco'' ("Moorish"). It soon became the standard term to refer to all former Muslims in Spain.

In Spanish America, ''morisco'' (or ''morisca'', in feminine form) was used to identify a racial category: a mixed-race ''casta

() is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas it also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical f ...

'', the child of a Spaniard (''español'') and a mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese ...

(offspring of a Spaniard and a ''negro'', generally a lighter-complected person with some African ancestry). The term appears in colonial-era marriage registers identifying individuals and in eighteenth-century ''casta'' paintings.

Demographics

There is no universally agreed figure of Morisco population. Estimates vary because of the lack of precise census. In addition, the Moriscos avoided registration and authorities in order to appear as members of the majority Spanish population. Furthermore, the populations would have fluctuated, due to such factors as birth rates, conquests, conversions, relocations, and emigration. Historians generally agree that, based on expulsion records, around 275,000 Moriscos were expelled from Spain in the early 17th century. HistorianL. P. Harvey

Leonard Patrick Harvey (often credited L. P. Harvey, 25 February 1929-4 August 2018) held lectureships in Spanish at Oxford University (1956–58), Southampton (1958–60), and Queen Mary College, London (1960–63), was Head of the Spanish Depa ...

in 2005 gave a range of 300,000 to 330,000 for the early 16th century; based on earlier estimates by Domínguez Ortiz and Bernard Vincent

Bernard (''Bernhard'') is a French and West Germanic masculine given name. It is also a surname.

The name is attested from at least the 9th century. West Germanic ''Bernhard'' is composed from the two elements ''bern'' "bear" and ''hard'' "brav ...

, who gave 321,000 for the period 1568–75, and 319,000 just before the expulsion in 1609. But, Christiane Stallaert put the number at around one million Moriscos at the beginning of the 16th century. Recent studies by Trevor Dadson

Trevor ( Trefor in the Welsh language) is a common given name or surname of Welsh origin. It is an habitational name, deriving from the Welsh ''tre(f)'', meaning "homestead", or "settlement" and ''fawr'', meaning "large, big". The Cornish langu ...

on the expulsion of the Moriscos propose the figure of 500,000 just before the expulsion, consistent with figures given by other historians. Dadson concludes that, assuming the 275,000 figure from the official expulsion records is correct, around 40% of Spain's Moriscos managed to avoid expulsions altogether. A further 20% managed to return to Spain in the years following their expulsion.

In the Kingdom of Granada

The

The Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions:R ...

was the last Muslim Kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula, which surrendered in 1492 to the Catholic forces after a decade-long campaign. Granada was annexed to Castile as the Kingdom of Granada, and had a majority Muslim population of between 250,000 and 300,000. Initially, the Treaty of Granada guaranteed their rights to be Muslim but Cardinal Cisneros

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, th ...

's effort to convert the population led to a series of rebellions. The rebellions were suppressed, and afterwards the Muslims in Granada were given the choice to remain and accept baptism, reject baptism and be enslaved or killed, or to be exiled. The option of exile was often not feasible in practice, and hindered by the authorities. Shortly after the rebellions' defeat, the entire Muslim population of Granada had nominally become Christian.

Although they converted to Christianity, they maintained their existing customs, including their language, distinct names, food, dress and even some ceremonies. Many secretly practiced Islam, even as they publicly professed and practiced Christianity. This led the Catholic rulers to adopt increasingly intolerant and harsh policies to eradicate these characteristics. This culminated in Philip II's ''Pragmatica'' of 1 January 1567 which ordered the Moriscos to abandon their customs, clothing and language. The ''pragmatica'' triggered the Morisco revolts in 1568–71. The Spanish authorities quashed this rebellion, and at the end of the fighting, the authorities decided to expel the Moriscos from Granada and scatter them to the other parts of Castile. Between 80,000 and 90,000 Granadans were marched to cities and towns across Castile.

In the Kingdom of Valencia

In 1492, the EasternKingdom of Valencia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, part of the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

had the second largest Muslim population in Spain after Granada, which became nominally the largest after the forced conversions in Granada in 1502. The nobles of Valencia continued to allow Islam to be practiced until the 1520s, and, to some extent, the Islamic legal system to be preserved.

In the 1520s, the Revolt of the Brotherhoods broke out among the Christian subjects of Valencia. The rebellion bore an anti-Islam sentiment, and the rebels forced Valencian Muslims to become Christians in the territories they controlled. The Muslims joined the Crown in suppressing the rebellion, playing crucial roles in several battles. After the rebellion was suppressed, King Charles V started an investigation to determine the validity of the conversions forced by the rebels. He ultimately upheld those conversions, therefore putting the force-converted subjects under the authority of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, and issued declarations to the effect of forcing the conversion of the rest of the Muslims.

After the forced conversions, Valencia was the region where the remains of Islamic culture was the strongest. A Venetian ambassador in the 1570s said that some Valencian nobles "had permitted their Moriscos to live almost openly as Mohammedans." Despite efforts to ban Arabic, it continued to be spoken until the expulsions. Valencians also trained other Aragonese Moriscos in Arabic and religious texts.

In Aragon and Catalonia

Moriscos accounted for 20% of the population of Aragon, residing principally on the banks of theEbro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

river and its tributaries. Unlike Granada and Valencia Moriscos, they did not speak Arabic but, as vassals of the nobility, were granted the privilege to practice their faith relatively openly.

Places like Muel, Zaragoza, were inhabited fully by Moriscos, the only Old Christians

Old Christian ( es, cristiano viejo, pt, cristão-velho, ca, cristià vell) was a social and law-effective category used in the Iberian Peninsula from the late 15th and early 16th century onwards, to distinguish Portuguese and Spanish people att ...

were the priest, the notary and the owner of the tavern-inn. "The rest would rather go on a pilgrimage to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

than Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

." quoting Enrique Cock, ''Relación del viaje hecho por Felipe III en 1585 a Zaragoza, Barcelona y Valencia'', Madrid, 1876, page 314

In Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, Moriscos represented less than 2% of the population and were concentrated in the Low Ebro region, as well as in the city of Lleida

Lleida (, ; Spanish: Lérida ) is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital city of the province of Lleida.

Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Central Depression. It is also the capital city of the Segrià comarca, a ...

and the towns of Aitona and Seròs, in the Low Segre region. They largely spoke Arabic no longer, but Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

, and to a lesser extent also Castilian- Aragonese in Lleida

Lleida (, ; Spanish: Lérida ) is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital city of the province of Lleida.

Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Central Depression. It is also the capital city of the Segrià comarca, a ...

.

In Castile

The Kingdom of Castile included also Extremadura and much of modern-day Andalusia (particularly theGuadalquivir

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from the Gul ...

Valley). The proportion of its population in most of its territory was more dispersed except in specific locations such as Villarrubia de los Ojos, Hornachos, Arévalo or the ''Señorío de las Cinco Villas'' (in the southwestern part of the province of Albacete

Albacete ( es, Provincia de Albacete, ) is a province of central Spain, in the southern part of the autonomous community of Castile–La Mancha. As of 2012, Albacete had a population of 402,837 people. Its capital city, also called Albacete, is ...

), where they were the majority or even the totality of the population. Castile's Moriscos were highly integrated and practically indistinguishable from the Catholic population: they did not speak Arabic and a large number of them were genuine Christians. The mass arrival of the much more visible Morisco population deported from Granada to the lands under the Kingdom of Castile led to a radical change in the situation of Castilian Moriscos, despite their efforts to distinguish themselves from the Granadans. For example, marriages between Castilian Moriscos and "old" Christians were much more common than between Castilian and Granadan Moriscos. The town of Hornachos was an exception, not only because practically all of its inhabitants were Moriscos but because of their open practice of the Islamic faith and of their famed independent and indomitable nature. For this reason, the order of expulsion in Castile targeted specifically the "''Hornacheros''", the first Castilian Moriscos to be expelled. The Hornacheros were exceptionally allowed to leave fully armed and were marched as an undefeated army to Seville from where they were transported to Morocco. They maintained their combative nature overseas, founding the Corsary Republic of Bou Regreg

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

and Salé

Salé ( ar, سلا, salā, ; ber, ⵙⵍⴰ, sla) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the right bank of the Bou Regreg river, opposite the national capital Rabat, for which it serves as a commuter town. Founded in about 1030 by the Banu Ifran, ...

in modern-day Morocco.

In the Canary Islands

The situation of the Moriscos in theCanary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

was different from on continental Europe. They were not the descendants of Iberian Muslims but were Muslim Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinc ...

taken from Northern Africa in Christian raids ('' cabalgadas'') or prisoners taken during the attacks of the Barbary Pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

against the islands. In the Canary Islands, they were held as slaves or freed, gradually converting to Christianity, with some serving as guides in raids against their former homelands. When the king forbade further raids, the Moriscos lost contact with Islam. They became a substantial part of the population of the islands, reaching one-half of the inhabitants of Lanzarote

Lanzarote (, , ) is a Spanish island, the easternmost of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean. It is located approximately off the north coast of Africa and from the Iberian Peninsula. Covering , Lanzarote is the fourth-largest of the i ...

. Protesting their Christianity, they managed to avoid the expulsion that affected European Moriscos. Still subjected to the ethnic discrimination of the '' pureza de sangre'', they could not migrate to the Americas or join many organizations. Later petitions allowed for their emancipation with the rest of the Canarian population.

Religion

Christianity

While theMoors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinc ...

chose to leave Spain and emigrate to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, the Moriscos accepted Christianity and gained certain cultural and legal privileges for doing so.

Many Moriscos became devout in their new Christian faith, and in Granada, some Moriscos were killed by Muslims for refusing to renounce Christianity.: "In Granada, Moriscos were killed because they refused to renounce their adopted faith. Elsewhere in Spain, Moriscos went to mass and heard confession and appeared to do everything that their new faith required of them." In 16th century Granada, the Christian Moriscos chose the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

as their patroness saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or person.

...

and developed Christian devotional literature

Christian devotional literature (also called devotionals or Christian living literature) is religious writing that Christian individuals read for their personal growth and spiritual formation. Such literature often takes the form of Christian da ...

with a Marian emphasis.

Islam

Because conversions to Christianity were decreed by law rather than by their own will, most Moriscos still genuinely believed in Islam. Because of the danger associated with practicing Islam, however, the religion was largely practiced clandestinely. A legal opinion, called "theOran fatwa

The Oran fatwa was a ''responsum'' fatwa, or an Islamic legal opinion, issued in 1502 to address the crisis that occurred when Muslims in the Crown of Castile (in Spain) were forced to convert to Christianity in 15001502. The fatwa sets out ...

" by modern scholars, circulated in Spain and provided religious justification for outwardly conforming to Christianity while maintaining an internal conviction of faith in Islam, when necessary for survival. The fatwa affirmed the regular obligations of a Muslim, including the ritual prayer (''salat

(, plural , romanized: or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːh, ( or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːtʰin construct state) ), also known as ( fa, نماز) and also spelled , are prayers performed by Muslims. Facing the , the direction of the Kaaba with ...

'') and the ritual alms (''zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ...

''), although the obligation might be fulfilled in a relaxed manner (e.g., the fatwa mentioned making the ritual prayer "even though by making some slight movement" and the ritual alms by "showing generosity to a beggar"). The fatwa also allowed Muslims to perform acts normally forbidden in Islamic law, such as consuming pork and wine, calling Jesus the son of God, and blaspheming against the prophet Muhammad, as long as they maintained conviction against such acts.

The writing of a Morisco crypto-Muslim author known as the "Young Man of Arévalo

The Young Man of Arévalo ( es, el Mancebo de Arévalo) was a Morisco crypto-Muslim author from Arévalo, Castile who was the most productive known Islamic author in Spain during the period after the forced conversion of Muslims there. He travel ...

" included accounts of his travel around Spain, his meetings with other clandestine Muslims and descriptions of their religious practices and discussions. The writing referred to the practice of secret congregational ritual prayer, ('' salat jama'ah'') collecting alms in order to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried o ...

(although it is unclear whether the journey was ultimately achieved), and the determination and hope to reinstitute the full practice of Islam as soon as possible. The Young Man wrote at least three extant works, ''Brief compendium of our sacred law and sunna'', the ''Tafsira'' and ''Sumario de la relación y ejercio espiritual'', all written in Spanish with Arabic script (''aljamiado''), and primarily about religious topics.

Extant copies of the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

were also found from the Morisco period, although many are not complete copies but selections of ''sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

s'', which were easier to hide. Other surviving Islamic religious materials from this period include collections of ''hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

s'', stories of the prophets, Islamic legal texts, theological works (including Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

's works), as well as polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

al literature defending Islam and criticizing Christianity.

The Moriscos also likely wrote the Lead Books of Sacromonte

The Lead Books of Sacromonte ( es, Los Libros Plúmbeos del Sacromonte) are a series of texts inscribed on circular lead leaves, now considered to be 16th century forgeries.

History

The Lead Books were discovered in the caves of Sacromonte, a ...

, texts written in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

claiming to be Christian sacred books from the first century AD. Upon their discovery in the mid-1590s, the books were initially greeted enthusiastically by the Christians of Granada and treated by the Christian authorities as genuine and caused a sensation throughout Europe due to their (ostensibly) ancient origin. Hispano-Arabic historian Leonard Patrick Harvey proposed that the Moriscos wrote these texts in order to infiltrate Christianity from within, by emphasizing aspects of Christianity which were acceptable to Muslims. The content of the text was superficially Christian and did not refer to Islam at all, but contained many "Islamizing" features. The text never featured the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

doctrine or referred to Jesus as Son of God, concepts which are blasphemous and offensive in Islam. Instead, it repeatedly stated "There is no god but God and Jesus is the Spirit of God (''ruh Allah'')", which is unambiguously close to the Islamic shahada

The ''Shahada'' ( Arabic: ٱلشَّهَادَةُ , "the testimony"), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there i ...

and referred to the Qur'anic epithet for Jesus, "the Spirit of God". It contained passages which appeared (unbeknownst to the Christians at the time) to implicitly predict the arrival of Muhammad by mentioning his various Islamic epithets.

In many ways, the above situation was comparable to that of the Marrano

Marranos were Spanish and Portuguese Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity during the Middle Ages, but continued to practice Judaism in secrecy.

The term specifically refers to the char ...

s, secret Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s who lived in Spain at the same time.

Timeline

Conquest of al-Andalus

Islam has been present in Spain since the

Islam has been present in Spain since the Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, also known as the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, was the initial expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate over Hispania (in the Iberian Peninsula) from 711 to 718. The conquest resulted in the decline of t ...

in the eighth century. At the beginning of the twelfth century, the Muslim population in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

— called "Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

" by the Muslims — was estimated to number as high as 5.5 million, among whom were Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

and indigenous converts. In the next few centuries, as the Christians pushed from the north in a process called ''reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

'', the Muslim population declined. At the end of the fifteenth century, the ''reconquista'' culminated in the fall of Granada and the total number of Muslims in Spain was estimated to be between 500,000 and 600,000 out of the total Spanish population of 7 to 8 million. Approximately half of the remaining Muslims lived in the former Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions:R ...

, the last independent Muslim state in Spain, which had been annexed to the Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

. About 20,000 Muslims lived in other territories of Castile, and most of the remainder lived in the territories of the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

. Prior to this in Castile 200,000 of the 500,000 Muslims had been forcibly converted; 200,000 had left and 100,000 had died or been enslaved.

The Christians called the defeated Muslims who came in their rule the ''Mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for M ...

s''. Prior to the completion of the ''Reconquista'', they were generally given freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

as terms of their surrender. For example, the Treaty of Granada, which governed the surrender of the emirate, guaranteed a set of rights to the conquered Muslims, including religious tolerance and fair treatment, in return for their capitulation.

Forced conversions of Muslims

When Christian conversion efforts on the part of Granada's first archbishop, Hernando de Talavera, were less than successful, Cardinal Jimenez de Cisneros took stronger measures: withforced conversion

Forced conversion is the adoption of a different religion or the adoption of irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which ...

s, burning Islamic texts, and prosecuting many of Granada's Muslims. In response to these and other violations of the Treaty, Granada's Muslim population rebelled in 1499. The revolt lasted until early 1501, giving the Castilian authorities an excuse to void the terms of the Treaty for Muslims. In 1501 the terms of the Treaty of Granada protections were abandoned.

In 1501 Castilian authorities delivered an ultimatum to Granada's Muslims: they could either convert to Christianity or be expelled. Most did convert, in order not to have their property and small children taken away from them. Many continued to dress in their traditional fashion, speak Arabic, and secretly practiced Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

(crypto-Muslims). The 1504 Oran fatwa

The Oran fatwa was a ''responsum'' fatwa, or an Islamic legal opinion, issued in 1502 to address the crisis that occurred when Muslims in the Crown of Castile (in Spain) were forced to convert to Christianity in 15001502. The fatwa sets out ...

provided scholarly religious dispensations and instructions about secretly practicing Islam while outwardly practicing Christianity. With the decline of Arabic culture, many used the ''aljamiado

''Aljamiado'' (; ; ar, عَجَمِيَة trans. ''ʿajamiyah'' ) or ''Aljamía'' texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Aragonese, Portuguese, S ...

'' writing system, i.e., Castilian or Aragonese texts in Arabic writing with scattered Arabic expressions. In 1502, Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 b ...

formally rescinded toleration of Islam for the entire Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th ce ...

. In 1508, Castilian authorities banned traditional Granadan clothing. With the 1512 Spanish invasion of Navarre, the Muslims of Navarre were ordered to convert or leave by 1515.

However, King Ferdinand, as ruler of the Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

, continued to tolerate the large Muslim population living in his territory. Since the crown of Aragon was juridically independent of Castile, their policies towards Muslims could and did differ during this period. Historians have suggested that the Crown of Aragon was inclined to tolerate Islam in its realm because the landed nobility there depended on the cheap, plentiful labor of Muslim vassals.Henry Kamen, ''Spanish Inquisition'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997, p. 216) However, the landed elite's exploitation of Aragon's Muslims also exacerbated class resentments. In the 1520s, when Valencian guilds rebelled against the local nobility in the Revolt of the Brotherhoods, the rebels "saw that the simplest way to destroy the power of the nobles in the countryside would be to free their vassals, and this they did by baptizing them." The Inquisition and monarchy decided to prohibit the forcibly baptized Muslims of Valencia from returning to Islam. Finally, in 1526, King Charles V issued a decree compelling all Muslims in the crown of Aragon to convert to Catholicism or leave the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal had already expelled or forcibly converted its Muslims in 1497 and would establish its own Inquisition in 1536).

After the conversion

In Granada for the first decades after the conversion, the former Muslim elites of the former Emirate became the middlemen between the crown and the Morisco population. Certain religious tolerance, too, was still observable during the first half of the 16th century. They became '' alguaciles'', '' hidalgos'', courtiers, advisors to the royal court and translators of Arabic. They helped collect taxes (taxes from Granada made up one-fifth of Castile's income) and became the advocates and defenders of the Moriscos within royal circles. Some of them became genuine Christians while others secretly continued to be Muslims. The Islamic faith and tradition were more persistent among the Granadan lower class, both in the city and in the countryside. The city of Granada was divided into Morisco and Old Christian quarters, and the countryside often have alternating zones that are dominated by Old or New Christians. Royal and Church authorities tended to ignore the secret but persistent Islamic practice and tradition among some of the Morisco population. Outside Granada, the role of advocates and defenders were taken by the Morisco's Christian lords. In areas with high Morisco concentration, such as theKingdom of Valencia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

and certain areas of other kingdoms, former Muslims played an important role in the economy, especially in agriculture and craft. Consequently, the Christian lords often defended their Moriscos, sometimes to the point of being targeted by the Inquisition. For example, the Inquisition sentenced Sancho de Cardona, the Admiral of Aragon to life imprisonment after he was accused of allowing the Moriscos to openly practice Islam, build a mosque and openly made the ''adhan

Adhan ( ar, أَذَان ; also variously transliterated as athan, adhane (in French), azan/azaan (in South Asia), adzan (in Southeast Asia), and ezan (in Turkish), among other languages) is the Islamic call to public prayer ( salah) in a mo ...

'' (call to prayer). The Duke of Segorbe (later Viceroy of Valencia) allowed his vassal in the Vall d'Uixó to operate a '' madrassa''. A witness recalled one of his vassals saying that "we live as Moors and no one dares to say anything to us". A Venetian ambassador in the 1570s said that some Valencian nobles "had permitted their Moriscos to live almost openly as Mohammedans."

In 1567, Philip II directed Moriscos to give up their Arabic names and traditional dress, and prohibited the use of the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

language. In addition, the children of Moriscos were to be educated by Catholic priests. In reaction, there was a Morisco uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

in the Alpujarras from 1568 to 1571.

Expulsion

At the instigation of the

At the instigation of the Duke of Lerma

Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, 5th Marquess of Denia, 1st Count of Ampudia (1552/1553 – 17 May 1625), was a favourite of Philip III of Spain, the first of the ''validos'' ('most worthy') through whom the later ...

and the Viceroy of Valencia, Archbishop Juan de Ribera

Juan de Ribera (Seville, Spain, 20 March 1532 – Valencia, 6 January 1611) was an influential figure in 16th and 17th century Spain. Ribera held appointments as Archbishop and Viceroy of Valencia, Latin Patriarchate of Antioch, Commander in ...

, Philip III expelled the Moriscos from Spain between 1609 (Aragon) and 1614 (Castile). They were ordered to depart "under the pain of death and confiscation, without trial or sentence... to take with them no money, bullion, jewels or bills of exchange... just what they could carry." Estimates for the number expelled have varied, although contemporary accounts set the number at between 270,000 and 300,000 (about 4% of the Spanish population).

The majority were expelled from the Crown of Aragon (modern day Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia), particularly from Valencia, where Morisco communities remained large, visible and cohesive; and Christian animosity was acute, particularly for economic reasons. Some historians have blamed the subsequent economic collapse of the Spanish Eastern Mediterranean coast on the region's inability to replace Morisco workers successfully with Christian newcomers. Many villages were totally abandoned as a result. New laborers were fewer in number and were not as familiar with local agricultural techniques.

In the Kingdom of Castille (including Andalusia, Murcia and the former kingdom of Granada), by contrast, the scale of Morisco expulsion was much less severe. This was due to the fact that their presence was less felt as they were considerably more integrated in their communities, enjoying the support and sympathy from local Christian populations, authorities and, in some occasions, the clergy. Furthermore, the internal dispersion of the more distinct Morisco communities of Granada throughout Castile and Andalusia after the War of the Alpujarras, made this community of Moriscos harder to track and identify, allowing them to merge with and disappear into the wider society.

crypto-Muslims

Crypto-Islam is the secret adherence to Islam while publicly professing to be of another faith; people who practice crypto-Islam are referred to as "crypto-Muslims." The word has mainly been used in reference to Spanish Muslims and Sicilian Musl ...

), but expelling their children presented the government with a dilemma. As the children had all been baptized, the government could not legally or morally transport them to Muslim lands. Some authorities proposed that children should be forcibly separated from their parents, but sheer numbers showed this to be impractical. Consequently, the official destination of the expellees was generally stated to be France (more specifically Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

). After the assassination of Henry IV in 1610, about 150,000 Moriscos were sent there. Many of the Moriscos migrated from Marseille to other lands in Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

, including Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, or Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Estimates of returnees vary, with historian Earl Hamilton believing that as many as a quarter of those expelled may have returned to Spain.

The overwhelming majority of the refugees settled in Muslim-held lands, mostly in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

(Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

) or Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

.

However they were ill-fitted with their Spanish language and customs.

International relations

FrenchHuguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s were in contact with the Moriscos in plans against the House of Austria (Habsburgs), which ruled Spain in the 1570s. Around 1575, plans were made for a combined attack of Aragonese Moriscos and Huguenots from Béarn

The Béarn (; ; oc, Bearn or ''Biarn''; eu, Bearno or ''Biarno''; or ''Bearnia'') is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three B ...

under Henri de Navarre

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarch ...

against Spanish Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

, in agreement with the king of Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, but these projects floundered with the arrival of John of Austria

John of Austria ( es, Juan, link=no, german: Johann; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the natural son born to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V late in life when he was a widower. Charles V met his son only once, recognizing him in a secret ...

in Aragon and the disarmament of the Moriscos.Henry Charles Lea, ''The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion''p. 281 In 1576, the Ottomans planned to send a three-pronged fleet from

Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

, to disembark between Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

; the French Huguenots would invade from the north and the Moriscos accomplish their uprising, but the Ottoman fleet failed to arrive.

Spanish spies reported that the Ottoman Emperor

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

Selim II

Selim II (Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى ''Selīm-i sānī'', tr, II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond ( tr, Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunk ( tr, Sarhoş Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire f ...

was planning to attack Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

in the Mediterranean below Sicily, and from there advance to Spain. It was reported Selim wanted to incite an uprising among Spanish Moriscos. In addition, "some four thousand Turks and Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

had come into Spain to fight alongside the insurgents in the Alpujarras",Kamen, ''Spanish Inquisition'', p. 224. a region near Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

and an obvious military threat. "The excesses committed on both sides were without equal in the experience of contemporaries; it was the most savage war to be fought in Europe that century." After the Castilian forces defeated the Islamic insurgents, they expelled some eighty thousand Moriscos from the Granada Province. Most settled elsewhere in Castile. The 'Alpujarras Uprising' hardened the attitude of the monarchy. As a consequence, the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

increased prosecution and persecution of Moriscos after the uprising.

Literature

Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

' writings, such as ''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of West ...

'' and '' Conversation of the Two Dogs'', offer ambivalent views of Moriscos.

In the first part of ''Don Quixote'' (before the expulsion), a Morisco translates a found document containing the Arabic "history" that Cervantes is merely "publishing". In the second part, after the expulsion, Ricote is a Morisco and a former neighbor of Sancho Panza. He cares more about money than religion, and left for Germany, from where he returned as a false pilgrim to unbury his treasure. He admits, however, the righteousness of their expulsion. His daughter Ana Félix is brought to Berbery but suffers since she is a sincere Christian.

Toward the end of the 16th century, Morisco writers challenged the perception that their culture was alien to Spain. Their literary works expressed early Spanish history in which Arabic-speaking Spaniards played a positive role. Chief among such works is ''Verdadera historia del rey don Rodrigo'' by Miguel de Luna (c. 1545–1615).

Aftermath

Scholars have noted that many Moriscos joined theBarbary Corsairs

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe a ...

, who had a network of bases from Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

to Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

and often attacked Spanish shipping and the Spanish coast. In the Corsair Republic of Sale, they became independent of Moroccan authorities and profited off of trade and piracy.

Morisco mercenaries in the service of the Moroccan sultan, using arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es, crossed the Sahara and conquered Timbuktu

Timbuktu ( ; french: Tombouctou;

Koyra Chiini: ); tmh, label=Tuareg, script=Tfng, ⵜⵏⴱⴾⵜ, Tin Buqt a city in Mali, situated north of the Niger River. The town is the capital of the Tombouctou Region, one of the eight administrativ ...

and the Niger Curve in 1591. Their descendants formed the ethnic group of the Arma. A Morisco worked as a military advisor for Sultan Al-Ashraf Tumanbay II of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

(the last Egyptian Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

Sultan) during his struggle against the Ottoman invasion in 1517 led by Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

. The Morisco military advisor advised Sultan Tumanbay to use infantry armed with guns instead of depending on cavalry. Arabic sources recorded that Moriscos of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt joined Ottoman armies. Many Moriscos of Egypt joined the army in the time of Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

.

Modern studies in population genetics have attributed unusually high levels of recent North African ancestry in modern Spaniards to Moorish settlement during the Islamic period and, more specifically, to the substantial proportion of Morisco population which remained in Spain and avoided expulsion.

Moriscos in Spain after the expulsion

It is impossible to know how many Moriscos remained after the expulsion, with traditional Spanish historiography considering that none remained and initial academic estimates such as those of Lapeyre offering figures as low as ten or fifteen thousand remaining. However, recent studies have been challenging the traditional discourse on the supposed success of the expulsion in purging Spain of its Morisco population. Indeed, it seems that expulsion met widely differing levels of success, particularly between the two major Spanish crowns of Castile and Aragón and recent historical studies also agree that both the original Morisco population and the number of them who avoided expulsion is higher than was previously thought. One of the earliest re-examinations of Morisco expulsion was carried out by Trevor J. Dadson in 2007, devoting a significant section to the expulsion in Villarrubia de los Ojos in southern Castille. Villarubia's entire Morisco population were the target of three expulsions which they managed to avoid or from which they succeeded in returning from to their town of origin, being protected and hidden by their non-Morisco neighbours. Dadson provides numerous examples, of similar incidents throughout Spain whereby Moriscos were protected and supported by non-Moriscos and returned en masse from North Africa, Portugal or France to their towns of origin.

A similar study on the expulsion in Andalusia concluded it was an inefficient operation which was significantly reduced in its severity by resistance to the measure among local authorities and populations. It further highlights the constant flow of returnees from North Africa, creating a dilemma for the local inquisition who did not know how to deal with those who had been given no choice but to convert to Islam during their stay in Muslim lands as a result of the Royal Decree. Upon the coronation of Philip IV, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on returnees and in September 1628 the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion."

An investigation published in 2012 sheds light on the thousands of Moriscos who remained in the province of Granada alone, surviving both the initial expulsion to other parts of Spain in 1571 and the final expulsion of 1604. These Moriscos managed to evade in various ways the royal decrees, hiding their true origin thereafter. More surprisingly, by the 17th and 18th centuries much of this group accumulated great wealth by controlling the silk trade and also holding about a hundred public offices. Most of these lineages were nevertheless completely assimilated over generations despite their endogamic practices. A compact core of active crypto-Muslims was prosecuted by the Inquisition in 1727, receiving comparatively light sentences. These convicts kept alive their identity until the late 18th century.

The attempted expulsion of Moriscos from

One of the earliest re-examinations of Morisco expulsion was carried out by Trevor J. Dadson in 2007, devoting a significant section to the expulsion in Villarrubia de los Ojos in southern Castille. Villarubia's entire Morisco population were the target of three expulsions which they managed to avoid or from which they succeeded in returning from to their town of origin, being protected and hidden by their non-Morisco neighbours. Dadson provides numerous examples, of similar incidents throughout Spain whereby Moriscos were protected and supported by non-Moriscos and returned en masse from North Africa, Portugal or France to their towns of origin.