A Moon landing is the arrival of a

spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, ...

on the surface of the

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. This includes both crewed and robotic missions. The first human-made object to touch the Moon was the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's

Luna 2, on 13 September 1959.

The United States'

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

was the first crewed mission to land on the Moon, on 20 July 1969. There were

six crewed U.S. landings between 1969 and 1972, and numerous uncrewed landings, with no

soft landings happening between 22 August 1976 and 14 December 2013.

The United States is the only country to have successfully conducted crewed missions to the Moon, with the last departing the lunar surface in December 1972. All

soft landings took place on the

near side of the Moon until 3 January 2019, when the Chinese

Chang'e 4 spacecraft made the first landing on the

far side of the Moon.

Uncrewed landings

After the unsuccessful attempt by

Luna 1 to land on the Moon in 1959, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

performed the first hard Moon landing – "hard" meaning the spacecraft intentionally crashes into the Moon – later that same year with the

Luna 2

''Luna 2'' ( rus, Луна 2}), originally named the Second Soviet Cosmic Rocket and nicknamed Lunik 2 in contemporaneous media, was the sixth of the Soviet Union's Luna programme spacecraft launched to the Moon, E-1 No.7. It was the first spa ...

spacecraft, a feat the U.S. duplicated in 1962 with

Ranger 4. Since then, twelve Soviet and U.S. spacecraft have used braking rockets (

retrorockets) to make

soft landings and perform scientific operations on the lunar surface, between 1966 and 1976. In 1966, the USSR accomplished the first soft landings and took the first pictures from the lunar surface during the

Luna 9 and

Luna 13

Luna 13 (E-6M series) was an unmanned space mission of the Luna program.

Overview

The Luna 13 spacecraft was launched toward the Moon from an Earth-orbiting platform and accomplished a soft landing on 24 December 1966, in the region of Oceanus P ...

missions. The U.S. followed with five uncrewed

Surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

soft landings.

The Soviet Union achieved the first uncrewed lunar soil

sample return with the

Luna 16 probe on 24 September 1970. This was followed by

Luna 20 and

Luna 24 in 1972 and 1976, respectively. Following the failure at launch in 1969 of the first

Lunokhod

Lunokhod ( rus, Луноход, p=lʊnɐˈxot, "Moonwalker") was a series of Soviet robotic lunar rovers designed to land on the Moon between 1969 and 1977. Lunokhod 1 was the first roving remote-controlled robot to land on an extraterrestrial ...

,

Luna E-8 No.201, the

Luna 17 and

Luna 21 were successful uncrewed

lunar rover missions in 1970 and 1973.

Many missions were failures at launch. In addition, several uncrewed landing missions achieved the Lunar surface but were unsuccessful, including:

Luna 15,

Luna 18, and

Luna 23 all crashed on landing; and the U.S.

Surveyor 4 lost all radio contact only moments before its landing.

More recently, other nations have crashed spacecraft on the surface of the Moon at speeds of around , often at precise, planned locations. These have generally been end-of-life lunar orbiters that, because of system degradations, could no longer overcome

perturbations from lunar

mass concentrations ("mascons") to maintain their orbit. Japan's lunar orbiter

Hiten impacted the Moon's surface on 10 April 1993. The

European Space Agency

, owners =

, headquarters = Paris, Île-de-France, France

, coordinates =

, spaceport = Guiana Space Centre

, seal = File:ESA emblem seal.png

, seal_size = 130px

, image = Views in the Main Control Room (120 ...

performed a controlled crash impact with their orbiter

SMART-1 on 3 September 2006.

Indian Space Research Organisation

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO; ) is the national space agency of India, headquartered in Bengaluru. It operates under the Department of Space (DOS) which is directly overseen by the Prime Minister of India, while the Chairman o ...

(ISRO) performed a controlled crash impact with its

Moon Impact Probe (MIP) on 14 November 2008. The MIP was an ejected probe from the Indian

Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter and performed

remote sensing

Remote sensing is the acquisition of information about an object or phenomenon without making physical contact with the object, in contrast to in situ or on-site observation. The term is applied especially to acquiring information about Ear ...

experiments during its descent to the lunar surface.

The Chinese lunar orbiter

Chang'e 1 executed a controlled crash onto the surface of the Moon on 1 March 2009. The rover mission

Chang'e 3 soft-landed on 14 December 2013, as did its successor,

Chang'e 4, on 3 January 2019. All crewed and uncrewed

soft landings had taken place on the

near side of the Moon, until 3 January 2019 when the Chinese

Chang'e 4 spacecraft made the first landing on the

far side of the Moon.

On 22 February 2019, Israeli private space agency

SpaceIL launched spacecraft

Beresheet on board a Falcon 9 from Cape Canaveral, Florida with the intention of achieving a soft landing. SpaceIL lost contact with the spacecraft and it crashed into the surface on 11 April 2019.

Indian Space Research Organization

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO; ) is the national space agency of India, headquartered in Bengaluru. It operates under the Department of Space (DOS) which is directly overseen by the Prime Minister of India, while the Chairman ...

launched

Chandrayaan-2 on 22 July 2019 with landing scheduled on 6 September 2019. However, at an altitude of 2.1 km from the Moon a few minutes before soft landing, the lander lost contact with the control room.

Crewed landings

A total of twelve men have landed on the Moon. This was accomplished with two US pilot-astronauts flying a

Lunar Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

on each of six

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

missions across a 41-month period starting 20 July 1969, with

Neil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aeronautical engineer who became the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. He was also a naval aviator, test pilot, and university professor.

...

and

Buzz Aldrin

Buzz Aldrin (; born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr.; January 20, 1930) is an American former astronaut, engineer and fighter pilot. He made three spacewalks as pilot of the 1966 Gemini 12 mission. As the Lunar Module ''Eagle'' pilot on the 1969 A ...

on

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

, and ending on 14 December 1972 with

Gene Cernan and

Jack Schmitt on

Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walke ...

. Cernan was the last man to step off the lunar surface.

All Apollo lunar missions had a third crew member who remained on board the

command module. The last three missions included a drivable lunar rover, the

Lunar Roving Vehicle

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) is a battery-powered four-wheeled rover used on the Moon in the last three missions of the American Apollo program ( 15, 16, and 17) during 1971 and 1972. It is popularly called the Moon buggy, a play on the ...

, for increased mobility.

Scientific background

To get to the Moon, a spacecraft must first leave Earth's

gravity well

The Hill sphere of an astronomical body is the region in which it dominates the attraction of satellites. To be retained by a planet, a moon must have an orbit that lies within the planet's Hill sphere. That moon would, in turn, have a Hil ...

; currently, the only practical means is a

rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

. Unlike airborne vehicles such as

balloons

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light s ...

and

jets, a rocket can continue

accelerating in the

vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often ...

outside the

atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

.

Upon approach of the target moon, a spacecraft will be drawn ever closer to its surface at increasing speeds due to gravity. In order to land intact it must decelerate to less than about and be ruggedized to withstand a "hard landing" impact, or it must decelerate to negligible speed at contact for a "soft landing" (the only option for humans). The first three attempts by the U.S. to perform a successful hard Moon landing with a ruggedized

seismometer package in 1962 all failed.

The Soviets first achieved the milestone of a hard lunar landing with a ruggedized camera in 1966, followed only months later by the first uncrewed soft lunar landing by the U.S.

The speed of a crash landing on its surface is typically between 70 and 100% of the

escape velocity of the target moon, and thus this is the total velocity which must be shed from the target moon's gravitational attraction for a soft landing to occur. For Earth's Moon, the escape velocity is .

The change in velocity (referred to as a

delta-v) is usually provided by a landing rocket, which must be carried into space by the original

launch vehicle

A launch vehicle or carrier rocket is a rocket designed to carry a payload ( spacecraft or satellites) from the Earth's surface to outer space. Most launch vehicles operate from a launch pads, supported by a launch control center and sys ...

as part of the overall spacecraft. An exception is the soft moon landing on

Titan

Titan most often refers to:

* Titan (moon), the largest moon of Saturn

* Titans, a race of deities in Greek mythology

Titan or Titans may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Fictional entities

Fictional locations

* Titan in fiction, fictiona ...

carried out by the

''Huygens'' probe in 2005. As the moon with the thickest atmosphere, landings on Titan may be accomplished by using

atmospheric entry

Atmospheric entry is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. There are two main types of atmospheric entry: ''uncontrolled entry'', such as the en ...

techniques that are generally lighter in weight than a rocket with equivalent capability.

The Soviets succeeded in making the first crash landing on the Moon in 1959.

Crash landings

may occur because of malfunctions in a spacecraft, or they can be deliberately arranged for vehicles which do not have an onboard landing rocket. There have been

many such Moon crashes, often with their flight path controlled to impact at precise locations on the lunar surface. For example, during the Apollo program the

S-IVB third stage of the

Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

rocket as well as the spent ascent stage of the

Lunar Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

were deliberately crashed on the Moon several times to provide impacts registering as a

moonquake on

seismometers that had been left on the lunar surface. Such crashes were instrumental in mapping the

internal structure of the Moon.

To return to Earth, the escape velocity of the Moon must be overcome for the spacecraft to escape the

gravity well

The Hill sphere of an astronomical body is the region in which it dominates the attraction of satellites. To be retained by a planet, a moon must have an orbit that lies within the planet's Hill sphere. That moon would, in turn, have a Hil ...

of the Moon. Rockets must be used to leave the Moon and return to space. Upon reaching Earth, atmospheric entry techniques are used to absorb the

kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its acce ...

of a returning spacecraft and reduce its speed for safe landing. These functions greatly complicate a moon landing mission and lead to many additional operational considerations. Any moon departure rocket must first be carried to the Moon's surface by a moon landing rocket, increasing the latter's required size. The Moon departure rocket, larger moon landing rocket and any Earth atmosphere entry equipment such as heat shields and

parachute

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, w ...

s must in turn be lifted by the original launch vehicle, greatly increasing its size by a significant and almost prohibitive degree.

Political background

The intense efforts devoted in the 1960s to achieving first an uncrewed and then ultimately a human Moon landing become easier to understand in the political context of its historical era.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

had introduced many new and deadly innovations including

blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air ...

-style surprise attacks used in the

invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

and

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, and in the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

; the

V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

, a

ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within t ...

which killed thousands in attacks on London and

Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504, ; and the

atom bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, which killed hundreds of thousands in the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

. In the 1950s, tensions mounted between the two ideologically opposed superpowers of the United States and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

that had emerged as victors in the conflict, particularly after the development by both countries of the

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

.

Willy Ley

Willy or Willie is a masculine, male given name, often a diminutive form of William (given name), William or Wilhelm (name), Wilhelm, and occasionally a nickname. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

* Willie Aames (born 1960), American ...

wrote in 1957 that a rocket to the Moon "could be built later this year if somebody can be found to sign some papers".

On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union

launched ''

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

'' as the first

artificial satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisoto ...

to orbit the Earth and so initiated the

Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

. This unexpected event was a source of pride to the Soviets and shock to the U.S., who could now potentially be surprise attacked by nuclear-tipped Soviet rockets in under 30 minutes. Also, the steady beeping of the

radio beacon

In navigation, a radio beacon or radiobeacon is a kind of beacon, a device that marks a fixed location and allows direction-finding equipment to find relative bearing. But instead of employing visible light, radio beacons transmit electromagne ...

aboard ''Sputnik 1'' as it passed overhead every 96 minutes was widely viewed on both sides as effective propaganda to

Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

countries demonstrating the technological superiority of the Soviet

political system

In political science, a political system means the type of political organization that can be recognized, observed or otherwise declared by a state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official government decisions. It usually comp ...

compared to that of the U.S. This perception was reinforced by a string of subsequent rapid-fire Soviet space achievements. In 1959, the R-7 rocket was used to launch the first escape from Earth's gravity into a

solar orbit, the first crash impact onto the surface of the Moon, and the first photography of the never-before-seen

far side of the Moon. These were the

Luna 1,

Luna 2

''Luna 2'' ( rus, Луна 2}), originally named the Second Soviet Cosmic Rocket and nicknamed Lunik 2 in contemporaneous media, was the sixth of the Soviet Union's Luna programme spacecraft launched to the Moon, E-1 No.7. It was the first spa ...

, and

Luna 3 spacecraft.

The U.S. response to these Soviet achievements was to greatly accelerate previously existing military space and missile projects and to create a civilian space agency,

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

. Military efforts were initiated to develop and produce mass quantities of intercontinental ballistic missiles (

ICBMs

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

) that would bridge the so-called

missile gap and enable a policy of

deterrence to

nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

with the Soviets known as

mutual assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

or MAD. These newly developed

missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket ...

s were made available to civilians of NASA for various projects (which would have the added benefit of demonstrating the payload, guidance accuracy and reliabilities of U.S. ICBMs to the Soviets).

While NASA stressed peaceful and scientific uses for these rockets, their use in various

lunar exploration efforts also had secondary goal of realistic, goal-oriented testing of the missiles themselves and development of associated infrastructure, just as the Soviets were doing with their R-7.

Early Soviet uncrewed lunar missions (1958–1965)

After the

fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, historical records were released to allow the true accounting of Soviet lunar efforts. Unlike the U.S. tradition of assigning a particular mission name in advance of a launch, the Soviets assigned a public "

Luna" mission number only if a launch resulted in a spacecraft going beyond Earth orbit. The policy had the effect of hiding Soviet Moon mission failures from public view. If the attempt failed in Earth orbit before departing for the Moon, it was frequently (but not always) given a "

Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

" or "

Cosmos" Earth-orbit mission number to hide its purpose. Launch explosions were not acknowledged at all.

Early U.S. uncrewed lunar missions (1958–1965)

In contrast to Soviet lunar exploration triumphs in 1959, success eluded initial U.S. efforts to reach the Moon with the

Pioneer and

Ranger programs. Fifteen consecutive U.S. uncrewed lunar missions over a six-year period from 1958 to 1964 all failed their primary photographic missions; however, Rangers 4 and 6 successfully repeated the Soviet lunar impacts as part of their secondary missions.

Failures included three U.S. attempts

in 1962 to hard land small seismometer packages released by the main Ranger spacecraft. These surface packages were to use

retrorockets to survive landing, unlike the parent vehicle, which was designed to deliberately crash onto the surface. The final three Ranger probes performed successful high altitude lunar

reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

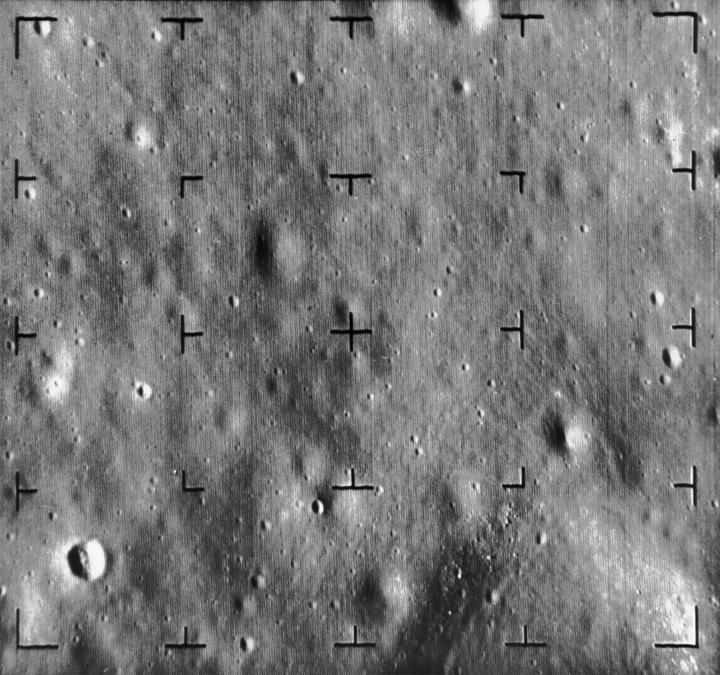

photography missions during intentional crash impacts between .

Pioneer missions

Three different designs of Pioneer lunar probes were flown on three different modified ICBMs. Those flown on the

Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

booster modified with an Able upper stage carried an

infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

image scanning television system with a

resolution of 1

milliradian to study the Moon's surface, an

ionization chamber to measure

radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

in space, a diaphragm/microphone assembly to detect

micrometeorites, a

magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

, and temperature-variable resistors to monitor spacecraft internal thermal conditions. The first, a mission managed by the

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

, exploded during launch; all subsequent Pioneer lunar flights had NASA as the lead management organization. The next two returned to Earth and burned up upon reentry into the atmosphere after achieved maximum altitudes of around and , far short of the roughly required to reach the vicinity of the Moon.

NASA then collaborated with the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

's

Ballistic Missile Agency to fly two extremely small cone-shaped probes on the

Juno ICBM, carrying only

photocells which would be triggered by the light of the Moon and a lunar radiation environment experiment using a

Geiger-Müller tube detector. The first of these reached an altitude of only around , serendipitously gathering data that established the presence of the

Van Allen radiation belts before reentering Earth's atmosphere. The second passed by the Moon at a distance of more than , twice as far as planned and too far away to trigger either of the on-board scientific instruments, yet still becoming the first U.S. spacecraft to reach a

solar orbit.

The final Pioneer lunar probe design consisted of four "

paddlewheel"

solar panels

A solar cell panel, solar electric panel, photo-voltaic (PV) module, PV panel or solar panel is an assembly of photovoltaic solar cells mounted in a (usually rectangular) frame, and a neatly organised collection of PV panels is called a photo ...

extending from a one-meter diameter spherical

spin-stabilized spacecraft body equipped to take images of the lunar surface with a television-like system, estimate the Moon's mass and topography of the

poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

, record the distribution and velocity of micrometeorites, study radiation, measure

magnetic fields, detect

low frequency electromagnetic waves in space and use a sophisticated integrated

propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived f ...

system for maneuvering and orbit insertion as well. None of the four spacecraft built in this series of probes survived launch on its

Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geogra ...

ICBM outfitted with an Able upper stage.

Following the unsuccessful Atlas-Able Pioneer probes, NASA's

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the City of La Cañada Flintridge, California, La Cañada Flintridge, California ...

embarked upon an uncrewed spacecraft development program whose modular design could be used to support both lunar and interplanetary exploration missions. The interplanetary versions were known as

Mariners; lunar versions were

Rangers. JPL envisioned three versions of the Ranger lunar probes: Block I prototypes, which would carry various radiation detectors in test flights to a very high Earth orbit that came nowhere near the Moon; Block II, which would try to accomplish the first Moon landing by hard landing a seismometer package; and Block III, which would crash onto the lunar surface without any braking rockets while taking very high resolution wide-area photographs of the Moon during their descent.

Ranger missions

The Ranger 1 and 2 Block I missions were virtually identical.

Spacecraft experiments included a

Lyman-alpha

The Lyman-alpha line, typically denoted by Ly-α, is a spectral line of hydrogen (or, more generally, of any one-electron atom) in the Lyman series. It is emitted when the atomic electron transitions from an ''n'' = 2 orbital to the ...

telescope, a

rubidium-vapor magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

, electrostatic analyzers, medium-energy-range

particle detectors, two triple coincidence telescopes, a cosmic-ray integrating

ionization chamber,

cosmic dust

Cosmic dust, also called extraterrestrial dust, star dust or space dust, is dust which exists in outer space, or has fallen on Earth. Most cosmic dust particles measure between a few molecules and 0.1 mm (100 micrometers). Larger particles are c ...

detectors, and

scintillation counter

A scintillation counter is an instrument for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation by using the excitation effect of incident radiation on a scintillating material, and detecting the resultant light pulses.

It consists of a scintillator wh ...

s. The goal was to place these Block I spacecraft in a very high Earth orbit with an apogee of and a

perigee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any el ...

of .

From that vantage point, scientists could make direct measurements of the

magnetosphere

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior d ...

over a period of many months while engineers perfected new methods to routinely track and communicate with spacecraft over such large distances. Such practice was deemed vital to be assured of capturing high-bandwidth television transmissions from the Moon during a one-shot fifteen-minute time window in subsequent Block II and Block III lunar descents. Both Block I missions suffered failures of the new Agena upper stage and never left low Earth

parking orbit after launch; both burned up upon reentry after only a few days.

The first attempts to perform a Moon landing took place in 1962 during the Rangers 3, 4 and 5 missions flown by the United States.

All three Block II missions basic vehicles were 3.1 m high and consisted of a lunar capsule covered with a balsa wood impact-limiter, 650 mm in diameter, a mono-propellant mid-course motor, a retrorocket with a thrust of ,

and a gold- and chrome-plated hexagonal base 1.5 m in diameter. This lander (code-named ''Tonto'') was designed to provide impact cushioning using an exterior blanket of crushable balsa wood and an interior filled with incompressible liquid

freon. A 42 kg (56 pounds) metal payload sphere floated and was free to rotate in a liquid freon reservoir contained in the landing sphere.

This payload sphere contained six silver-

cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12 element, group 12, zinc and mercury (element), mercury. Li ...

batteries to power a fifty-milliwatt radio transmitter, a temperature sensitive voltage controlled oscillator to measure lunar surface temperatures, and a seismometer designed with sensitivity high enough to detect the impact of a meteorite on the opposite side of the Moon. Weight was distributed in the payload sphere so it would rotate in its liquid blanket to place the seismometer into an upright and operational position no matter what the final resting orientation of the external landing sphere. After landing, plugs were to be opened allowing the freon to evaporate and the payload sphere to settle into upright contact with the landing sphere. The batteries were sized to allow up to three months of operation for the payload sphere. Various mission constraints limited the landing site to Oceanus Procellarum on the lunar equator, which the lander ideally would reach 66 hours after launch.

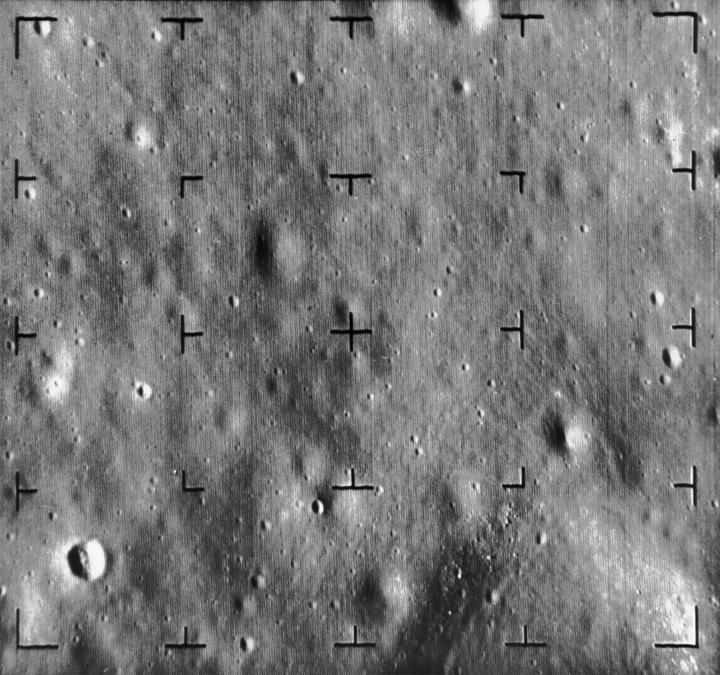

No cameras were carried by the Ranger landers, and no pictures were to be captured from the lunar surface during the mission. Instead, the Ranger Block II mother ship carried a 200-scan-line television camera to capture images during the free-fall descent to the lunar surface. The camera was designed to transmit a picture every 10 seconds.

Seconds before impact, at above the lunar surface, the Ranger mother ships took pictures (which may be viewe

here.

Other instruments gathering data before the mother ship crashed onto the Moon were a gamma ray spectrometer to measure overall lunar chemical composition and a radar altimeter. The radar altimeter was to give a signal ejecting the landing capsule and its solid-fueled braking rocket overboard from the Block II mother ship. The braking rocket was to slow and the landing sphere to a dead stop at above the surface and separate, allowing the landing sphere to free fall once more and hit the surface.

On Ranger 3, failure of the Atlas guidance system and a software error aboard the Agena upper stage combined to put the spacecraft on a course that would miss the Moon. Attempts to salvage lunar photography during a flyby of the Moon were thwarted by in-flight failure of the onboard flight computer. This was probably because of prior

heat sterilization

Sterilization refers to any process that removes, kills, or deactivates all forms of life (particularly microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, spores, and unicellular eukaryotic organisms) and other biological agents such as prions present ...

of the spacecraft by keeping it above the

boiling

Boiling is the rapid vaporization of a liquid, which occurs when a liquid is heated to its boiling point, the temperature at which the vapour pressure of the liquid is equal to the pressure exerted on the liquid by the surrounding atmosphere. Th ...

point of water for 24 hours on the ground, to protect the Moon from being contaminated by Earth organisms. Heat sterilization was also blamed for subsequent in-flight failures of the spacecraft computer on Ranger 4 and the power subsystem on Ranger 5. Only Ranger 4 reached the Moon in an uncontrolled crash impact on the far side of the Moon.

Heat sterilization was discontinued for the final four Block III Ranger probes. These replaced the Block II landing capsule and its retrorocket with a heavier, more capable television system to support landing site selection for upcoming Apollo crewed Moon landing missions. Six cameras were designed to take thousands of high-altitude photographs in the final twenty-minute period before crashing on the lunar surface. Camera resolution was 1,132 scan lines, far higher than the 525 lines found in a typical U.S. 1964 home television. While

Ranger 6 suffered a failure of this camera system and returned no photographs despite an otherwise successful flight, the subsequent

Ranger 7 mission to Mare Cognitum was a complete success.

Breaking the six-year string of failures in U.S. attempts to photograph the Moon at close range, the

Ranger 7 mission was viewed as a national turning point and instrumental in allowing the key 1965 NASA budget appropriation to pass through the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

intact without a reduction in funds for the Apollo crewed Moon landing program. Subsequent successes with

Ranger 8 and

Ranger 9 further buoyed U.S. hopes.

Soviet uncrewed soft landings (1966–1976)

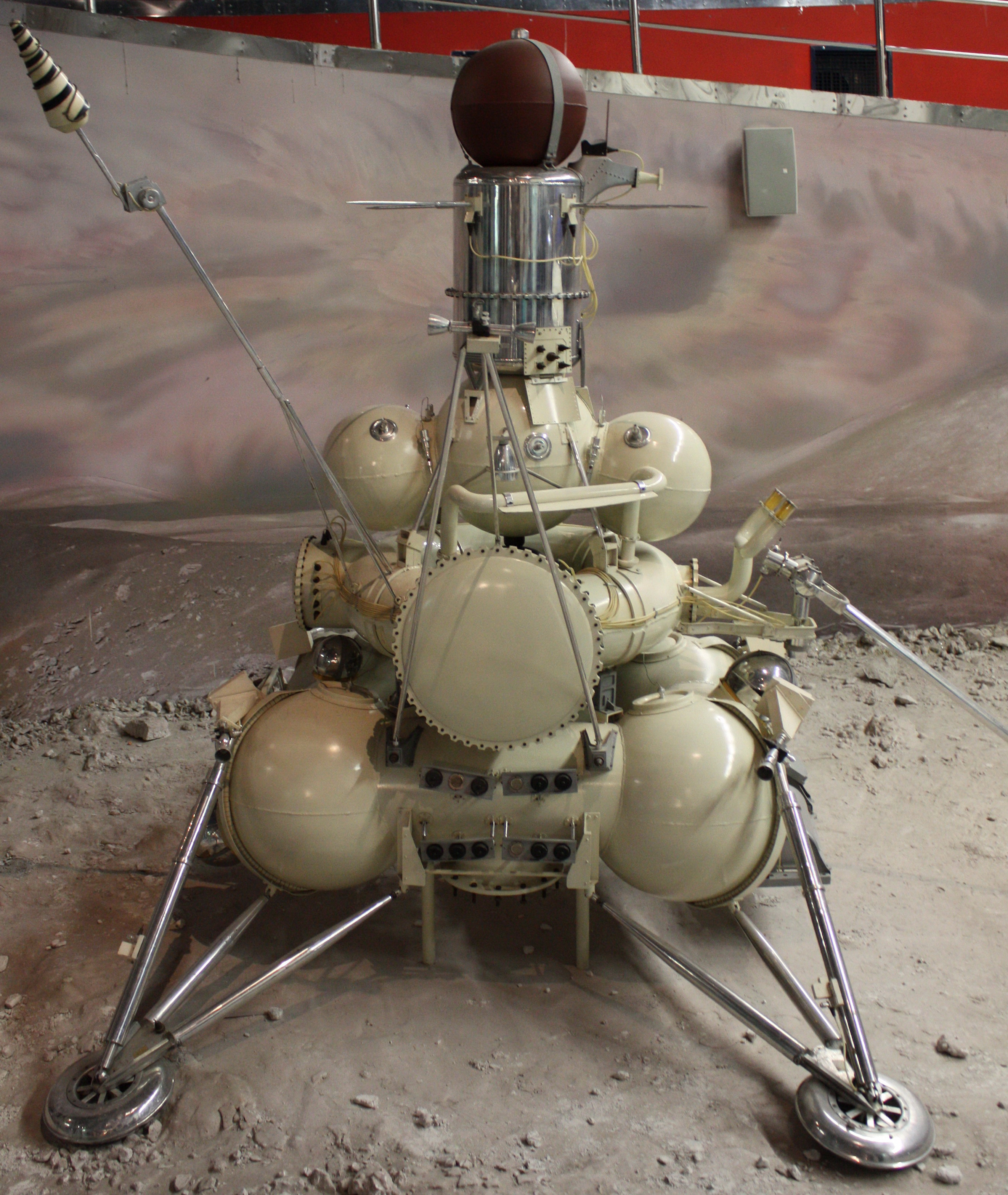

The

Luna 9 spacecraft, launched by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, performed the first successful soft Moon landing on 3 February 1966.

Airbags protected its ejectable capsule which survived an impact speed of over .

Luna 13

Luna 13 (E-6M series) was an unmanned space mission of the Luna program.

Overview

The Luna 13 spacecraft was launched toward the Moon from an Earth-orbiting platform and accomplished a soft landing on 24 December 1966, in the region of Oceanus P ...

duplicated this feat with a similar Moon landing on 24 December 1966. Both returned panoramic photographs that were the first views from the lunar surface.

Luna 16 was the first

robotic probe to land on the

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

and safely return a sample of lunar soil back to Earth. It represented the first

lunar sample return mission by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and was the third lunar

sample return mission overall, following the

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

and

Apollo 12

Apollo 12 (November 14–24, 1969) was the sixth crewed flight in the United States Apollo program and the second to land on the Moon. It was launched on November 14, 1969, by NASA from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Commander Charles ...

missions. This mission was later successfully repeated by

Luna 20 (1972) and

Luna 24 (1976).

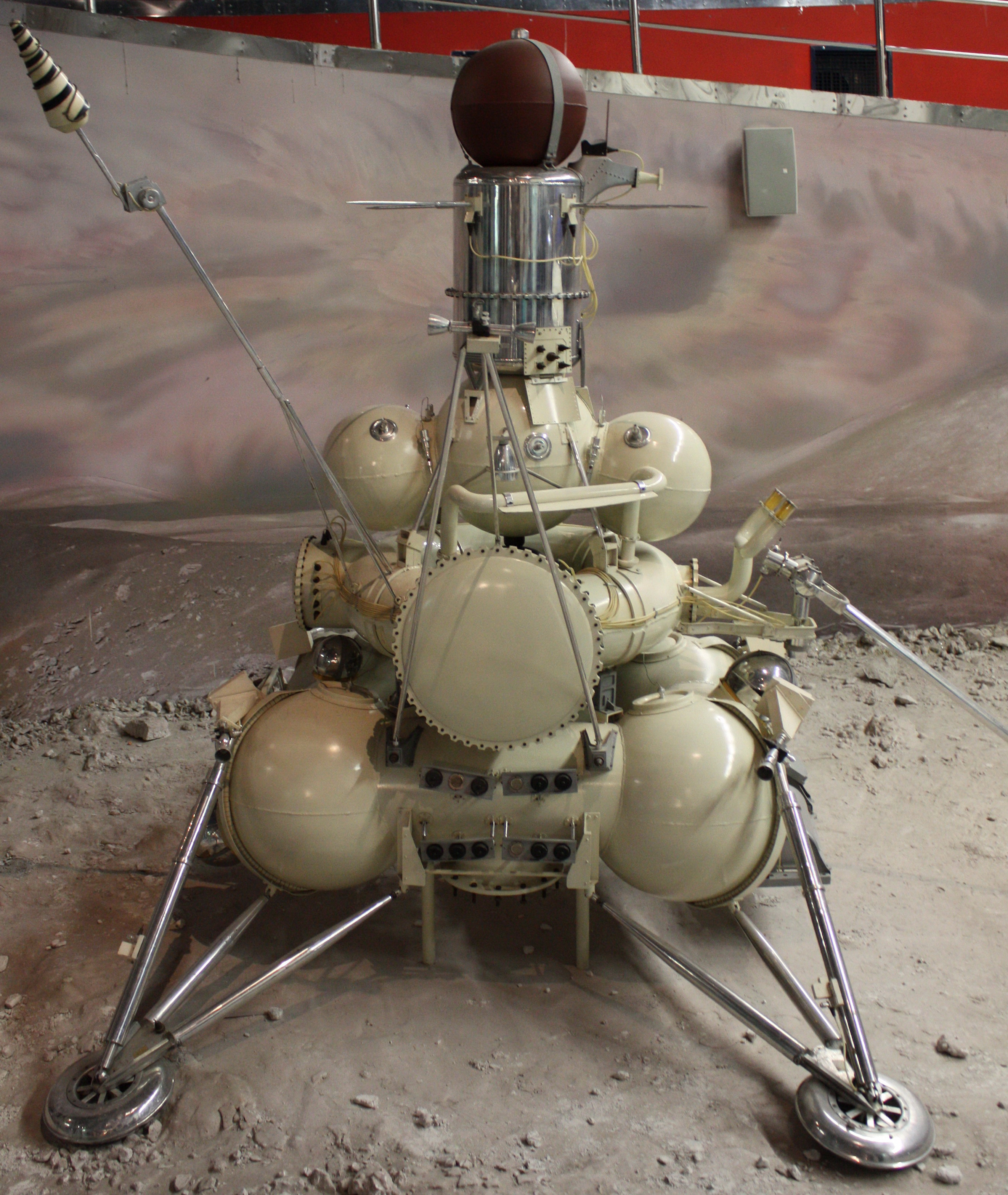

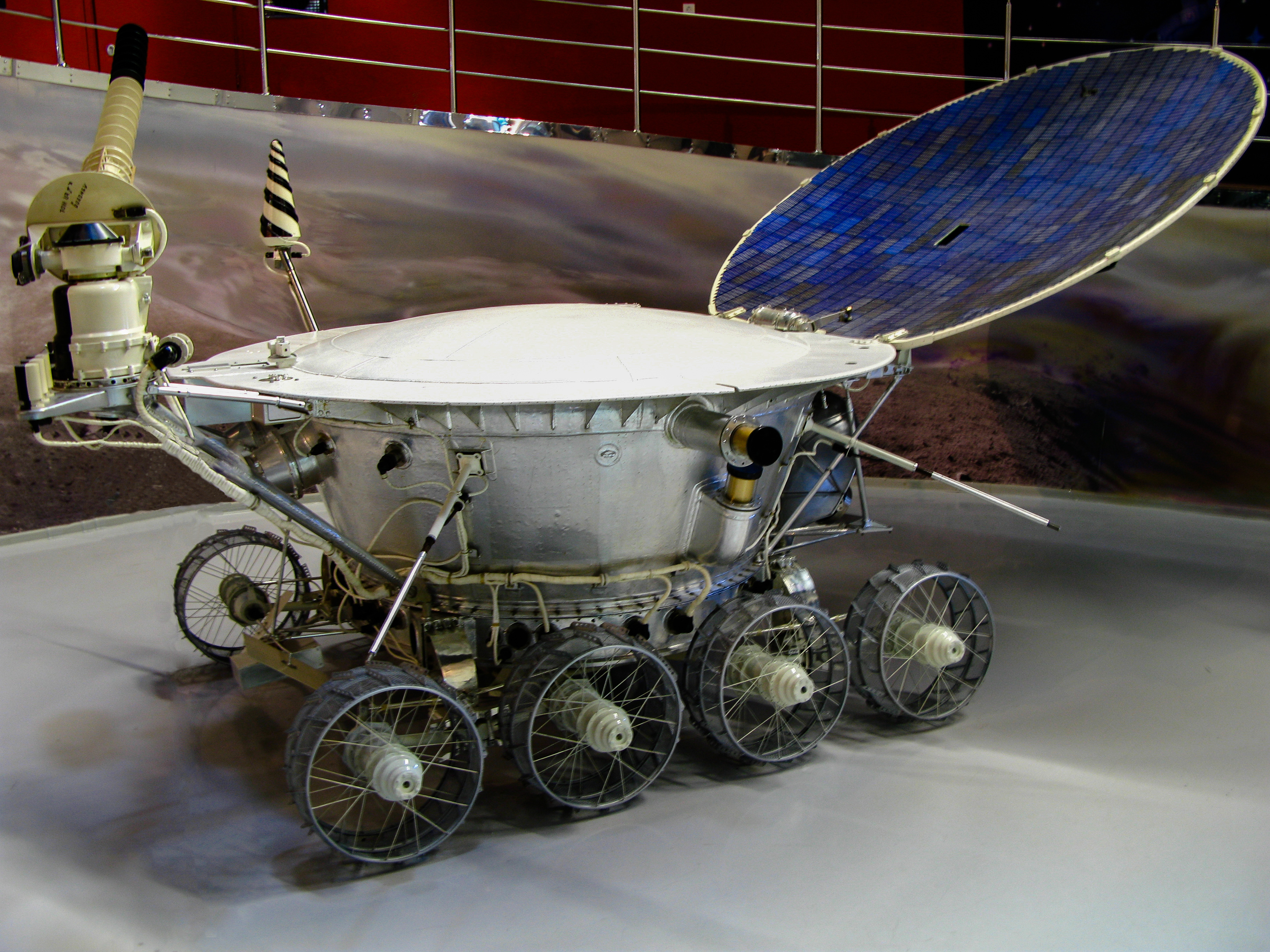

In 1970 and 1973 two

Lunokhod

Lunokhod ( rus, Луноход, p=lʊnɐˈxot, "Moonwalker") was a series of Soviet robotic lunar rovers designed to land on the Moon between 1969 and 1977. Lunokhod 1 was the first roving remote-controlled robot to land on an extraterrestrial ...

("Moonwalker") robotic lunar rovers were delivered to the Moon, where they successfully operated for 10 and 4 months respectively, covering 10.5 km (

Lunokhod 1) and 37 km (

Lunokhod 2). These rover missions were in operation concurrently with the Zond and Luna series of Moon flyby, orbiter and landing missions.

U.S. uncrewed soft landings (1966–1968)

The U.S.

robot

A robot is a machine—especially one programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the control may be embedded within. Robots may be ...

ic

Surveyor program was part of an effort to locate a safe site on the Moon for a human landing and test under lunar conditions the

radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

and landing systems required to make a true controlled touchdown. Five of Surveyor's seven missions made successful uncrewed Moon landings. Surveyor 3 was visited two years after its Moon landing by the crew of Apollo 12. They removed parts of it for examination back on Earth to determine the effects of long-term exposure to the lunar environment.

Transition from direct ascent landings to lunar orbit operations

Within four months of each other in early 1966 the Soviet Union and the United States had accomplished successful Moon landings with uncrewed spacecraft. To the general public both countries had demonstrated roughly equal technical capabilities by returning photographic images from the surface of the Moon. These pictures provided a key affirmative answer to the crucial question of whether or not lunar soil would support upcoming crewed landers with their much greater weight.

However, the Luna 9 hard landing of a ruggedized sphere using airbags at a ballistic impact speed had much more in common with the failed 1962 Ranger landing attempts and their planned impacts than with the Surveyor 1 soft landing on three footpads using its radar-controlled, adjustable-thrust retrorocket. While Luna 9 and Surveyor 1 were both major national accomplishments, only Surveyor 1 had reached its landing site employing key technologies that would be needed for a crewed flight. Thus as of mid-1966, the United States had begun to pull ahead of the Soviet Union in the so-called Space Race to land a man on the Moon.

Advances in other areas were necessary before crewed spacecraft could follow uncrewed ones to the surface of the Moon. Of particular importance was developing the expertise to perform flight operations in lunar orbit. Ranger, Surveyor and initial Luna Moon landing attempts all flew directly to the surface without a lunar orbit. Such

direct ascents use a minimum amount of fuel for uncrewed spacecraft on a one-way trip.

In contrast, crewed vehicles need additional fuel after a lunar landing to enable a return trip back to Earth for the crew. Leaving this massive amount of required Earth-return fuel in lunar orbit until it is used later in the mission is far more efficient than taking such fuel down to the lunar surface in a Moon landing and then hauling it all back into space yet again, working against lunar gravity both ways. Such considerations lead logically to a

lunar orbit rendezvous mission profile for a crewed Moon landing.

Accordingly, beginning in mid-1966 both the U.S. and U.S.S.R. naturally progressed into missions featuring lunar orbit as a prerequisite to a crewed Moon landing. The primary goals of these initial uncrewed orbiters were extensive photographic mapping of the entire lunar surface for the selection of crewed landing sites and, for the Soviets, the checkout of radio communications gear that would be used in future soft landings.

An unexpected major discovery from initial lunar orbiters were vast volumes of dense materials beneath the surface of the Moon's

maria. Such mass concentrations ("

mascons") can send a crewed mission dangerously off course in the final minutes of a Moon landing when aiming for a relatively small landing zone that is smooth and safe. Mascons were also found over a longer period of time to greatly disturb the orbits of low-altitude satellites around the Moon, making their orbits unstable and forcing an inevitable crash on the lunar surface in the relatively short period of months to a few years.

Controlling the location of impact for spent lunar orbiters can have scientific value. For example, in 1999 the NASA

Lunar Prospector

''Lunar Prospector'' was the third mission selected by NASA for full development and construction as part of the Discovery Program. At a cost of $62.8 million, the 19-month mission was designed for a low polar orbit investigation of the Moon ...

orbiter was deliberately targeted to impact a permanently shadowed area of Shoemaker Crater near the lunar south pole. It was hoped that energy from the impact would vaporize suspected shadowed ice deposits in the crater and liberate a water vapor plume detectable from Earth. No such plume was observed. However, a small vial of ashes from the body of pioneer lunar scientist

Eugene Shoemaker was delivered by the Lunar Prospector to the crater named in his honor – currently the only human remains on the Moon.

Soviet lunar orbit satellites (1966–1974)

Luna 10 became the first spacecraft to orbit the Moon on 3 April 1966.

U.S. lunar orbit satellites (1966–1967)

Soviet circumlunar loop flights (1967–1970)

It is possible to aim a spacecraft from Earth so it will loop around the Moon and return to Earth without entering lunar orbit, following the so-called

free return trajectory. Such circumlunar loop missions are simpler than lunar orbit missions because rockets for lunar orbit braking and Earth return are not required. However, a crewed circumlunar loop trip poses significant challenges beyond those found in a crewed low-Earth-orbit mission, offering valuable lessons in preparation for a crewed Moon landing. Foremost among these are mastering the demands of re-entering the Earth's atmosphere upon returning from the Moon.

Inhabited Earth-orbiting vehicles such as the Space Shuttle return to Earth from speeds of around . Due to the effects of gravity, a vehicle returning from the Moon hits Earth's atmosphere at a much higher speed of around . The

g-loading on astronauts during the resulting

deceleration can be at the limits of human endurance even during a nominal reentry. Slight variations in the vehicle flight path and reentry angle during a return from the Moon can easily result in fatal levels of deceleration force.

Achieving a crewed circumlunar loop flight prior to a crewed lunar landing became a primary goal of the Soviets with their

Zond spacecraft program. The first three Zonds were robotic planetary probes; after that, the Zond name was transferred to a completely separate human spaceflight program. The initial focus of these later Zonds was extensive testing of required high-speed reentry techniques. This focus was not shared by the U.S., who chose instead to bypass the stepping stone of a crewed circumlunar loop mission and never developed a separate spacecraft for this purpose.

Initial crewed spaceflights in the early 1960s placed a single person in low Earth orbit during the Soviet

Vostok and U.S.

Mercury programs. A two-flight extension of the Vostok program known as

Voskhod effectively used Vostok capsules with their ejection seats removed to achieve Soviet space firsts of multiple person crews in 1964 and spacewalks in early 1965. These capabilities were later demonstrated by the U.S. in ten

Gemini low Earth orbit missions throughout 1965 and 1966, using a totally new second-generation spacecraft design that had little in common with the earlier Mercury. These Gemini missions went on to prove techniques for orbital

rendezvous and docking crucial to a crewed lunar landing mission profile.

After the end of the Gemini program, the Soviet Union began flying their second-generation Zond crewed spacecraft in 1967 with the ultimate goal of looping a cosmonaut around the Moon and returning him or her immediately to Earth. The

Zond spacecraft was launched with the simpler and already operational

Proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

launch rocket, unlike the parallel Soviet human Moon landing effort also underway at the time based on third-generation

Soyuz spacecraft

Soyuz () is a series of spacecraft which has been in service since the 1960s, having made more than 140 flights. It was designed for the Soviet space program by the Korolev Design Bureau (now Energia). The Soyuz succeeded the Voskhod spacecr ...

requiring development of the advanced

N-1 booster. The Soviets thus believed they could achieve a crewed Zond circumlunar flight years before a U.S. human lunar landing and so score a propaganda victory. However, significant development problems delayed the Zond program and the success of the U.S. Apollo lunar landing program led to the eventual termination of the Zond effort.

Like Zond, Apollo flights were generally launched on a free return trajectory that would return them to Earth via a circumlunar loop if a

service module malfunction failed to place them in lunar orbit. This option was implemented after an explosion aboard the

Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

mission in 1970, which is the only crewed circumlunar loop mission flown to date.

Zond 5 was the first spacecraft to carry life from Earth to the vicinity of the Moon and return, initiating the final lap of the

Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

with its payload of tortoises, insects, plants, and bacteria. Despite the failure suffered in its final moments, the Zond 6 mission was reported by Soviet media as being a success as well. Although hailed worldwide as remarkable achievements, both these Zond missions flew off-nominal reentry trajectories resulting in deceleration forces that would have been fatal to humans.

As a result, the Soviets secretly planned to continue uncrewed Zond tests until their reliability to support human flight had been demonstrated. However, due to NASA's continuing problems with the

lunar module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

, and because of

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

reports of a potential Soviet crewed circumlunar flight in late 1968, NASA fatefully changed the flight plan of

Apollo 8

Apollo 8 (December 21–27, 1968) was the first crewed spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and the first human spaceflight to reach the Moon. The crew orbited the Moon ten times without landing, and then departed safely back to Earth. The ...

from an Earth-orbit lunar module test to a lunar orbit mission scheduled for late December 1968.

In early December 1968 the launch window to the Moon opened for the Soviet launch site in

Baikonur

Baikonur ( kk, Байқоңыр, ; russian: Байконур, translit=Baykonur), formerly known as Leninsk, is a city of republic significance in Kazakhstan on the northern bank of the Syr Darya river. It is currently leased and administered ...

, giving the USSR their final chance to beat the US to the Moon.

Cosmonauts

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally ...

went on alert and asked to fly the Zond spacecraft then in final countdown at Baikonur on the first human trip to the Moon. Ultimately, however, the Soviet

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

decided the risk of crew death was unacceptable given the combined poor performance to that point of Zond/Proton and so scrubbed the launch of a crewed Soviet lunar mission. Their decision proved to be a wise one, since this unnumbered Zond mission was destroyed in another uncrewed test when it was finally launched several weeks later.

By this time flights of the third generation U.S.

Apollo spacecraft had begun. Far more capable than the Zond, the Apollo spacecraft had the necessary rocket power to slip into and out of lunar orbit and to make course adjustments required for a safe reentry during the return to Earth. The

Apollo 8

Apollo 8 (December 21–27, 1968) was the first crewed spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and the first human spaceflight to reach the Moon. The crew orbited the Moon ten times without landing, and then departed safely back to Earth. The ...

mission carried out the first human trip to the Moon on 24 December 1968, certifying the

Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

booster for crewed use and flying not a circumlunar loop but instead a full ten orbits around the Moon before returning safely to Earth.

Apollo 10 then performed a full dress rehearsal of a crewed Moon landing in May 1969. This mission orbited within of the lunar surface, performing necessary low-altitude mapping of trajectory-altering mascons using a factory prototype lunar module too heavy to land. With the failure of the robotic Soviet sample return Moon landing attempt

Luna 15 in July 1969, the stage was set for

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

.

Human Moon landings (1969–1972)

US strategy

Plans for human Moon exploration began during the

Eisenhower administration. In a series of mid-1950s articles in ''

Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Coll ...

'' magazine,

Wernher von Braun had popularized the idea of a crewed expedition to establish a lunar base. A human Moon landing posed several daunting technical challenges to the US and USSR. Besides guidance and weight management,

atmospheric re-entry without

ablative overheating was a major hurdle. After the Soviets launched

Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

, von Braun promoted a plan for the US Army to establish a military lunar outpost by 1965.

After the

early Soviet successes, especially

Yuri Gagarin's flight, US President

John F. Kennedy looked for a project that would capture the public imagination. He asked Vice President

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

to make recommendations on a scientific endeavor that would prove US world leadership. The proposals included non-space options such as massive irrigation projects to benefit the

Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

. The Soviets, at the time, had more powerful rockets than the US, which gave them an advantage in some kinds of space mission.

Advances in US nuclear weapon technology had led to smaller, lighter warheads; the Soviets' were much heavier, and the powerful

R-7 rocket was developed to carry them. More modest missions such as flying around the Moon, or a space lab in lunar orbit (both were proposed by Kennedy to von Braun), offered too much advantage to the Soviets; ''landing'', however, would capture the world's imagination.

Johnson had championed the US human spaceflight program ever since Sputnik, sponsoring legislation to create NASA while he was still a senator. When Kennedy asked him in 1961 to research the best achievement to counter the Soviets' lead, Johnson responded that the US had an even chance of beating them to a crewed lunar landing, but not for anything less. Kennedy seized on Apollo as the ideal focus for efforts in space. He ensured continuing funding, shielding space spending from the 1963 tax cut, but diverting money from other NASA scientific projects. These diversions dismayed NASA's leader,

James E. Webb, who perceived the need for NASA's support from the scientific community.

The Moon landing required development of the large Saturn V

launch vehicle

A launch vehicle or carrier rocket is a rocket designed to carry a payload ( spacecraft or satellites) from the Earth's surface to outer space. Most launch vehicles operate from a launch pads, supported by a launch control center and sys ...

, which achieved a perfect record: zero catastrophic failures or launch vehicle-caused mission failures in thirteen launches.

For the program to succeed, its proponents would have to defeat criticism from politicians both on the left (more money for social programs) and on the right (more money for the military). By emphasizing the scientific payoff and playing on fears of Soviet space dominance, Kennedy and Johnson managed to swing public opinion: by 1965, 58 percent of Americans favored Apollo, up from 33 percent two years earlier. After Johnson

became President in 1963, his continuing defense of the program allowed it to succeed in 1969, as Kennedy had planned.

Soviet strategy

Soviet leader

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

said in October 1963 the USSR was "not at present planning flight by cosmonauts to the Moon," while insisting that the Soviets had not dropped out of the race. Only after another year did the USSR fully commit itself to a Moon-landing attempt, which ultimately failed.

At the same time, Kennedy had suggested various joint programs, including a possible Moon landing by Soviet and U.S. astronauts and the development of better weather-monitoring satellites, eventually resulting in the

Apollo-Soyuz mission. Khrushchev, sensing an attempt by Kennedy to steal Russian space technology, rejected the idea at first: if the USSR went to the Moon, it would go alone. Though Khrushchev was eventually warming up to the idea, but the realization of a joint Moon landing was choked by Kennedy's assassination.

, the

Soviet space program's chief designer, had started promoting his

Soyuz craft and the

N1 launcher rocket that would have the capability of carrying out a human Moon landing. Khrushchev directed Korolev's design bureau to arrange further space firsts by modifying the existing Vostok technology, while a second team started building a completely new launcher and craft, the Proton booster and the Zond, for a human cislunar flight in 1966. In 1964 the new Soviet leadership gave Korolev the backing for a Moon landing effort and brought all crewed projects under his direction.

With Korolev's death and the failure of the first Soyuz flight in 1967, coordination of the Soviet Moon landing program quickly unraveled. The Soviets built a landing craft and selected cosmonauts for a mission that would have placed

Alexei Leonov

Alexei Arkhipovich Leonov. (30 May 1934 – 11 October 2019) was a Soviet and Russian cosmonaut, Air Force major general, writer, and artist. On 18 March 1965, he became the first person to conduct a spacewalk, exiting the capsule during t ...

on the Moon's surface, but with the successive launch failures of the N1 booster in 1969, plans for a crewed landing suffered first delay and then cancellation.

A program of automated return vehicles was begun, in the hope of being the first to return lunar rocks. This had several failures. It eventually succeeded with

Luna 16 in 1970. But this had little impact, because the Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 lunar landings and rock returns had already taken place by then.

Apollo missions

In total, twenty-four U.S. astronauts have traveled to the Moon. Three have made the trip twice, and twelve have walked on its surface. Apollo 8 was a lunar-orbit-only mission, Apollo 10 included undocking and Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI), followed by LM staging to CSM redocking, while Apollo 13, originally scheduled as a landing, ended up as a lunar fly-by, by means of

free return trajectory; thus, none of these missions made landings. Apollo 7 and Apollo 9 were Earth-orbit-only missions. Apart from the inherent dangers of crewed Moon expeditions as seen with Apollo 13, one reason for their cessation according to astronaut

Alan Bean is the cost it imposes in government subsidies.

Human Moon landings

Other aspects of the successful Apollo landings

President Richard Nixon had speechwriter

William Safire

William Lewis Safire (; Safir; December 17, 1929 – September 27, 2009Safire, William (1986). ''Take My Word for It: More on Language.'' Times Books. . p. 185.) was an American author, columnist, journalist, and presidential speechwriter. He ...

prepare a condolence speech for delivery in case Armstrong and Aldrin became marooned on the Moon's surface and could not be rescued.

In 1951, science fiction writer

Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

forecast that a man would reach the Moon by 1978.

On 16 August 2006, the

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

reported that NASA is

missing the original Slow-scan television tapes (which were made before the scan conversion for conventional TV) of the Apollo 11 Moon walk. Some news outlets have mistakenly reported the SSTV tapes found in Western Australia, but those tapes were only recordings of data from the Apollo 11

Early Apollo Surface Experiments Package. The tapes were found in 2008 and sold at auction in 2019 for the 50th anniversary of the landing.

Scientists believe the six American flags planted by astronauts have been bleached white because of more than 40 years of exposure to solar radiation.

Using

LROC

LRoc (born James Elbert Phillips) is an American in-house songwriter and producer at Jermaine Dupri's So So Def Recordings. He has co-written and co-produced singles like Janet Jackson's " Call on Me", Monica's " Everytime Tha Beat Drop", Mari ...

images, five of the six American flags are still standing and casting shadows at all of the sites, except Apollo 11.

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin reported that the flag was blown over by the exhaust from the ascent engine during liftoff of Apollo 11.

["Apollo Moon Landing Flags Still Standing, Photos Reveal"](_blank)

Space.com. Retrieved 10 October 2014

Late 20th century–Early 21st century uncrewed crash landings

Hiten (Japan)

Launched on 24 January 1990, 11:46 UTC. At the end of its mission, the Japanese lunar orbiter

Hiten was commanded to crash into the lunar surface and did so on 10 April 1993 at 18:03:25.7 UT (11 April 03:03:25.7 JST).

Lunar Prospector (US)

Lunar Prospector

''Lunar Prospector'' was the third mission selected by NASA for full development and construction as part of the Discovery Program. At a cost of $62.8 million, the 19-month mission was designed for a low polar orbit investigation of the Moon ...

was launched on 7 January 1998. The mission ended on 31 July 1999, when the orbiter was deliberately crashed into a crater near the lunar south pole after the presence of water ice was successfully detected.

SMART-1 (ESA)

Launched 27 September 2003, 23:14 UTC from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana. At the end of its mission, the

ESA lunar orbiter

SMART-1 performed a controlled crash into the Moon, at about 2 km/s. The time of the crash was 3 September 2006, at 5:42 UTC.

Chandrayaan-1 (India)

The impactor, the

Moon Impact Probe, an instrument on

Chandrayaan-1 mission, impacted near

Shackleton crater at the south pole of the lunar surface at 14 November 2008, 20:31 IST.

Chandrayaan-1 was launched on 22 October 2008, 00:52 UTC.

Chang'e 1 (China)

The Chinese lunar orbiter

Chang'e 1, executed a controlled crash onto the surface of the Moon on 1 March 2009, 20:44 GMT, after a 16-month mission.

Chang'e 1 was launched on 24 October 2007, 10:05 UTC.

SELENE (Japan)

SELENE or ''Kaguya'' after successfully orbiting the Moon for a year and eight months, the main orbiter was instructed to impact on the lunar surface near the crater

Gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

at 18:25 UTC on 10 June 2009.

or ''Kaguya'' was launched on 14 September 2007.

LCROSS (US)

The

LCROSS

The Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) was a robotic spacecraft operated by NASA. The mission was conceived as a low-cost means of determining the nature of hydrogen detected at the polar regions of the Moon. Launched immed ...

data collecting shepherding spacecraft was launched together with the

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) is a NASA robotic spacecraft currently orbiting the Moon in an eccentric polar mapping orbit. Data collected by LRO have been described as essential for planning NASA's future human and robotic missions t ...

(LRO) on 18 June 2009 on board an

Atlas V

Atlas V is an expendable launch system and the fifth major version in the Atlas launch vehicle family. It was originally designed by Lockheed Martin, now being operated by United Launch Alliance (ULA), a joint venture between Lockheed Mart ...

rocket with a

Centaur

A centaur ( ; grc, κένταυρος, kéntauros; ), or occasionally hippocentaur, is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse.

Centaurs are thought of in many Greek myths as bein ...

upper stage. On 9 October 2009, at 11:31

UTC, the Centaur upper stage impacted the lunar surface, releasing the kinetic

energy equivalent of detonating approximately 2 tons of

TNT (8.86

GJ). Six minutes later at 11:37 UTC, the LCROSS shepherding spacecraft also impacted the surface.

GRAIL (US)

The

GRAIL mission consisted of two small spacecraft: GRAIL A (''Ebb''), and GRAIL B (''Flow''). They were launched on 10 September 2011 on board a

Delta II

Delta II was an expendable launch system, originally designed and built by McDonnell Douglas. Delta II was part of the Delta rocket family and entered service in 1989. Delta II vehicles included the Delta 6000, and the two later Delta 7000 va ...

rocket. GRAIL A separated from the rocket about nine minutes after launch, and GRAIL B followed about eight minutes later. The first probe entered orbit on 31 December 2011 and the second followed on 1 January 2012. The two spacecraft impacted the Lunar surface on 17 December 2012.

LADEE (US)

LADEE

The Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE; ) was a NASA lunar exploration and technology demonstration mission. It was launched on a Minotaur V rocket from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on September 7, 2013. During its ...

was launched on 7 September 2013.

The mission ended on 18 April 2014, when the spacecraft's controllers intentionally crashed LADEE into the

far side of the Moon,

which, later, was determined to be near the eastern rim of

Sundman V crater.

Manfred Memorial Moon Mission (Luxemburg)

The

Manfred Memorial Moon Mission was launched on the 23 October 2014. It conducted a lunar flyby and operated for 19 days which was four times longer than expected. The Manfred Memorial Moon Mission remained attached to the upper stage of its launch vehicle (CZ-3C/E). The spacecraft along with its upper stage impacted the Moon on 4 March 2022.

21st century uncrewed soft landings and attempts

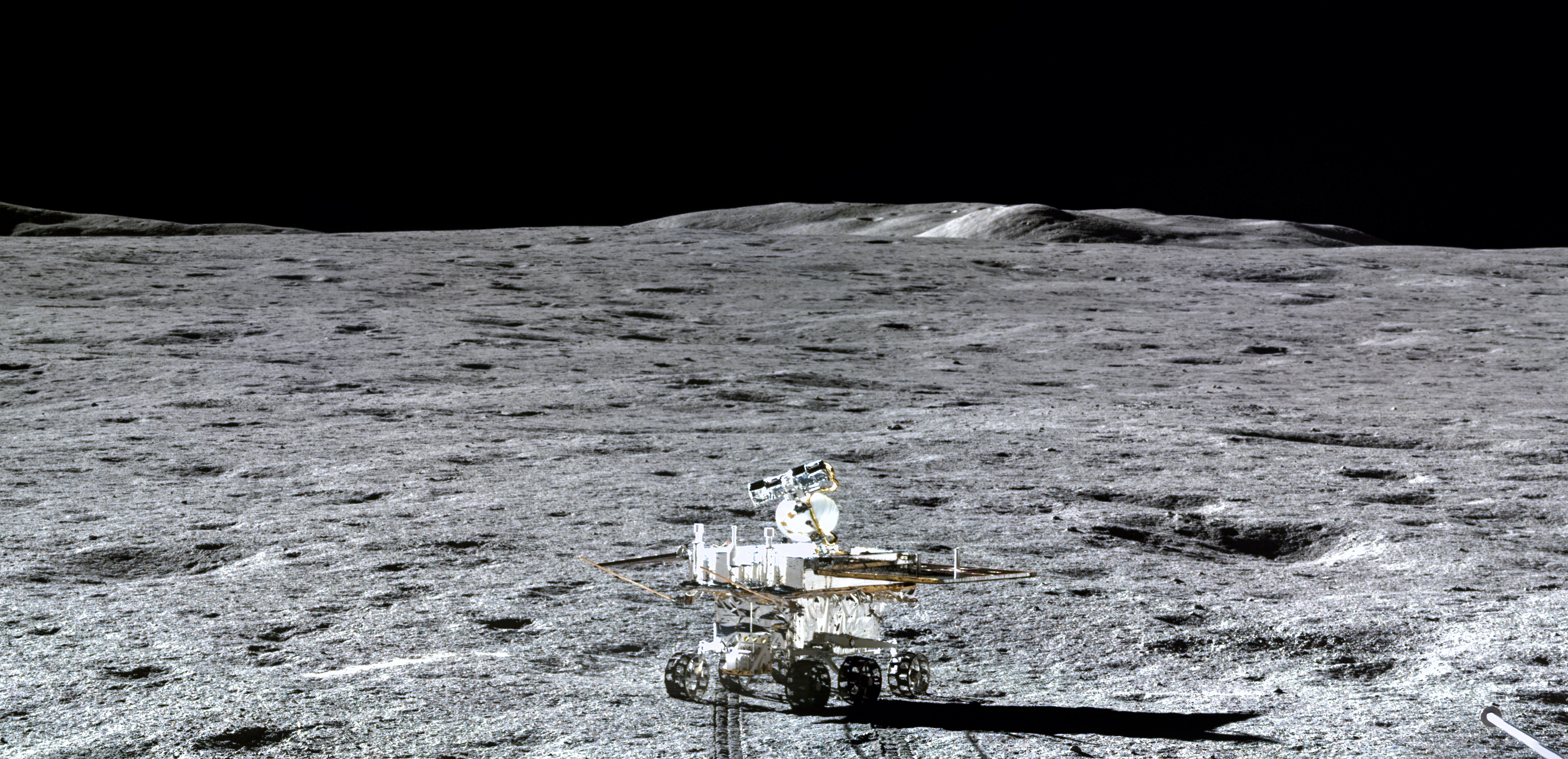

Chang'e 3 (China)

On 14 December 2013 at 13:12 UTC

Chang'e 3 soft-landed a

rover

Rover may refer to:

People

* Constance Rover (1910–2005), English historian

* Jolanda de Rover (born 1963), Dutch swimmer

* Rover Thomas (c. 1920–1998), Indigenous Australian artist

Places

* Rover, Arkansas, US

* Rover, Missouri, US

* ...

on the Moon. This was China's first soft landing on another celestial body and world's first lunar soft landing since

Luna 24 on 22 August 1976. The mission was launched on 1 December 2013. After successful landing, the lander release the

Yutu rover

''Yutu'' () was a robotic lunar rover that formed part of the Chinese Chang'e 3 mission to the Moon. It was launched at 17:30 UTC on 1 December 2013, and reached the Moon's surface on 14 December 2013. The mission marks the first soft landing ...

, which moved 114 meters before being immobilized due to system malfunction. But the rover was still operational until July 2016.

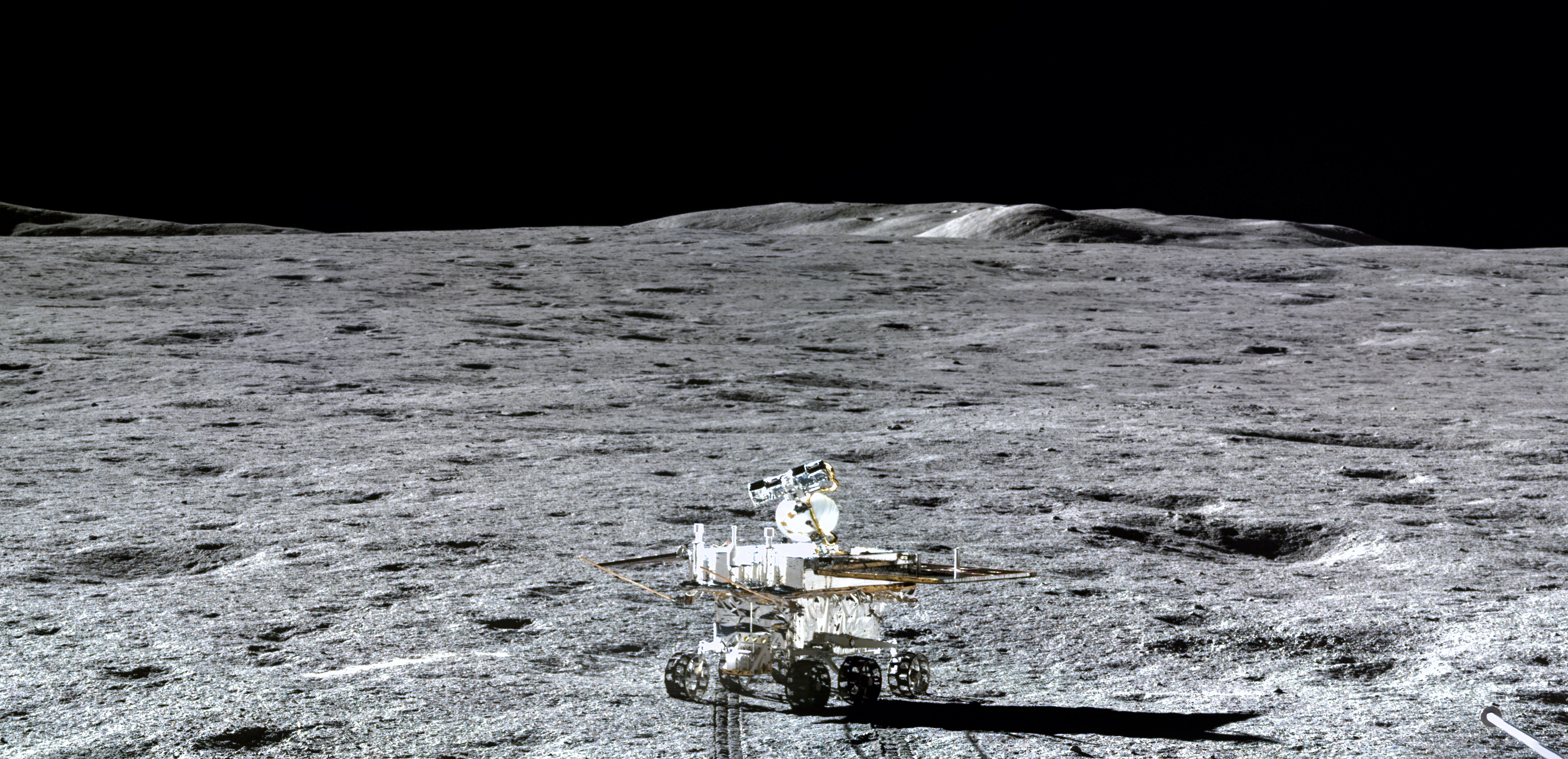

Chang'e 4 (China)

On 3 January 2019 at 2:26 UTC

Chang'e 4 became the first spacecraft to land on the

far side of the Moon.

Chang'e 4 was originally designed as the backup of Chang'e 3. It was later adjusted as a mission to the far side of the Moon after the success of Chang'e 3. After making a successful landing within

Von Kármán crater, the Chang'e 4 lander deployed the 140kg

Yutu-2 rover and began human's very first close exploration of the far side of the Moon. Because the Moon blocks the communications between far side and the earth, a relay satellite,

Queqiao, was launched to the Earth–Moon L2

Lagrangian point

In celestial mechanics, the Lagrange points (; also Lagrangian points or libration points) are points of equilibrium for small-mass objects under the influence of two massive orbiting bodies. Mathematically, this involves the solution of t ...

a few months prior to the landing to enable communications.

Yutu-2, the second lunar rover from China, was equipped with panoramic camera, lunar penetrating radar, visible and near-infrared Imaging spectrometer and advanced small analyzer for neutrals. As of July 2022, it has survived more than 1000 days on the lunar surface and is still driving with cumulative travel distance of over 1200 meters.

''Beresheet'' (Israel)

On 22 February 2019 at 01:45 UTC,

SpaceX

Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American spacecraft manufacturer, launcher, and a satellite communications corporation headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the stated goal o ...

launched the ''

Beresheet'' lunar lander, developed by Israel's