Monteverdi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both

There is no clear record of Monteverdi's early musical training, or evidence that (as is sometimes claimed) he was a member of the Cathedral choir or studied at Cremona University. Monteverdi's first published work, a set of

There is no clear record of Monteverdi's early musical training, or evidence that (as is sometimes claimed) he was a member of the Cathedral choir or studied at Cremona University. Monteverdi's first published work, a set of

In the dedication of his second book of madrigals, Monteverdi had described himself as a player of the ''vivuola'' (which could mean either

In the dedication of his second book of madrigals, Monteverdi had described himself as a player of the ''vivuola'' (which could mean either

At the turn of the 17th century, Monteverdi found himself the target of musical controversy. The influential Bolognese theorist

At the turn of the 17th century, Monteverdi found himself the target of musical controversy. The influential Bolognese theorist

Martinengo had been ill for some time before his death and had left the music of San Marco in a fragile state. The choir had been neglected and the administration overlooked. When Monteverdi arrived to take up his post, his principal responsibility was to recruit, train, discipline and manage the musicians of San Marco (the ''capella''), who amounted to about 30 singers and six instrumentalists; the numbers could be increased for major events.Fabbri (2007), pp. 128–129 Among the recruits to the choir was Francesco Cavalli, who joined in 1616 at the age of 14; he was to remain connected with San Marco throughout his life, and was to develop a close association with Monteverdi.Walker and Alm (n.d.) Monteverdi also sought to expand the repertory, including not only the traditional '' a cappella'' repertoire of Roman and Flemish composers, but also examples of the modern style which he favoured, including the use of continuo and other instruments. Apart from this he was of course expected to compose music for all the major feasts of the church. This included a new

Martinengo had been ill for some time before his death and had left the music of San Marco in a fragile state. The choir had been neglected and the administration overlooked. When Monteverdi arrived to take up his post, his principal responsibility was to recruit, train, discipline and manage the musicians of San Marco (the ''capella''), who amounted to about 30 singers and six instrumentalists; the numbers could be increased for major events.Fabbri (2007), pp. 128–129 Among the recruits to the choir was Francesco Cavalli, who joined in 1616 at the age of 14; he was to remain connected with San Marco throughout his life, and was to develop a close association with Monteverdi.Walker and Alm (n.d.) Monteverdi also sought to expand the repertory, including not only the traditional '' a cappella'' repertoire of Roman and Flemish composers, but also examples of the modern style which he favoured, including the use of continuo and other instruments. Apart from this he was of course expected to compose music for all the major feasts of the church. This included a new  Monteverdi also received commissions from other Italian states and from their communities in Venice. These included, for the Milanese community in 1620, music for the Feast of

Monteverdi also received commissions from other Italian states and from their communities in Venice. These included, for the Milanese community in 1620, music for the Feast of

There is a consensus among music historians that a period extending from the mid-15th century to around 1625, characterised in

There is a consensus among music historians that a period extending from the mid-15th century to around 1625, characterised in

Ingegneri, Monteverdi's first tutor, was a master of the '' musica reservata'' vocal style, which involved the use of chromatic progressions and

Ingegneri, Monteverdi's first tutor, was a master of the '' musica reservata'' vocal style, which involved the use of chromatic progressions and

The opera opens with a brief trumpet

The opera opens with a brief trumpet

The ''Vespro della Beata Vergine'', Monteverdi's first published sacred music since the ''Madrigali spirituali'' of 1583, consists of 14 components: an introductory versicle and response, five psalms interspersed with five "sacred concertos" (Monteverdi's term),Whenham (1997), pp. 16–17 a hymn, and two Magnificat settings. Collectively these pieces fulfil the requirements for a Vespers service on any feast day of the Virgin. Monteverdi employs many musical styles; the more traditional features, such as

The ''Vespro della Beata Vergine'', Monteverdi's first published sacred music since the ''Madrigali spirituali'' of 1583, consists of 14 components: an introductory versicle and response, five psalms interspersed with five "sacred concertos" (Monteverdi's term),Whenham (1997), pp. 16–17 a hymn, and two Magnificat settings. Collectively these pieces fulfil the requirements for a Vespers service on any feast day of the Virgin. Monteverdi employs many musical styles; the more traditional features, such as

During this period of his Venetian residency, Monteverdi composed quantities of sacred music. Numerous motets and other short works were included in anthologies by local publishers such as Giulio Cesare Bianchi (a former student of Monteverdi) and Lorenzo Calvi, and others were published elsewhere in Italy and Austria.Whenham (2007) "The Venetian Sacred Music", pp. 200–201 The range of styles in the motets is broad, from simple

During this period of his Venetian residency, Monteverdi composed quantities of sacred music. Numerous motets and other short works were included in anthologies by local publishers such as Giulio Cesare Bianchi (a former student of Monteverdi) and Lorenzo Calvi, and others were published elsewhere in Italy and Austria.Whenham (2007) "The Venetian Sacred Music", pp. 200–201 The range of styles in the motets is broad, from simple

The last years of Monteverdi's life were much occupied with opera for the Venetian stage.

The last years of Monteverdi's life were much occupied with opera for the Venetian stage.

Interest in Monteverdi revived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries among music scholars in Germany and Italy, although he was still regarded as essentially a historical curiosity. Wider interest in the music itself began in 1881, when Robert Eitner published a shortened version of the ''Orfeo'' score. Around this time Kurt Vogel scored the madrigals from the original manuscripts, but more critical interest was shown in the operas, following the discovery of the ''L'incoronazione'' manuscript in 1888 and that of ''Il ritorno'' in 1904. Largely through the efforts of Vincent d'Indy, all three operas were staged in one form or another, during the first quarter of the 20th century: ''L'Orfeo'' in May 1911, ''L'incoronazione'' in February 1913 and ''Il ritorno'' in May 1925.

The Italian nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio lauded Monteverdi and in his novel ''Il fuoco'' (1900) wrote of "''il divino Claudio'' ... what a heroic soul, purely Italian in its essence!" His vision of Monteverdi as the true founder of Italian musical lyricism was adopted by musicians who worked with the regime of Benito Mussolini (1922–1945), including

Interest in Monteverdi revived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries among music scholars in Germany and Italy, although he was still regarded as essentially a historical curiosity. Wider interest in the music itself began in 1881, when Robert Eitner published a shortened version of the ''Orfeo'' score. Around this time Kurt Vogel scored the madrigals from the original manuscripts, but more critical interest was shown in the operas, following the discovery of the ''L'incoronazione'' manuscript in 1888 and that of ''Il ritorno'' in 1904. Largely through the efforts of Vincent d'Indy, all three operas were staged in one form or another, during the first quarter of the 20th century: ''L'Orfeo'' in May 1911, ''L'incoronazione'' in February 1913 and ''Il ritorno'' in May 1925.

The Italian nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio lauded Monteverdi and in his novel ''Il fuoco'' (1900) wrote of "''il divino Claudio'' ... what a heroic soul, purely Italian in its essence!" His vision of Monteverdi as the true founder of Italian musical lyricism was adopted by musicians who worked with the regime of Benito Mussolini (1922–1945), including  The revival of public interest in Monteverdi's music gathered pace in the second half of the 20th century, reaching full spate in the general early-music revival of the 1970s, during which time the emphasis turned increasingly towards "authentic" performance using historical instruments. The magazine '' Gramophone'' notes over 30 recordings of the ''Vespers'' between 1976 and 2011, and 27 of ''Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda'' between 1971 and 2013. Monteverdi's surviving operas are today regularly performed; the website

The revival of public interest in Monteverdi's music gathered pace in the second half of the 20th century, reaching full spate in the general early-music revival of the 1970s, during which time the emphasis turned increasingly towards "authentic" performance using historical instruments. The magazine '' Gramophone'' notes over 30 recordings of the ''Vespers'' between 1976 and 2011, and 27 of ''Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda'' between 1971 and 2013. Monteverdi's surviving operas are today regularly performed; the website

Crticial editions

of Monteverdi's complete madrigals and arias by the

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

and sacred music

Religious music (also sacred music) is a type of music that is performed or composed for religious use or through religious influence. It may overlap with ritual music, which is music, sacred or not, performed or composed for or as ritual. Relig ...

, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered a crucial transitional figure between the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

and Baroque periods of music history.

Born in Cremona, where he undertook his first musical studies and compositions, Monteverdi developed his career first at the court of Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

() and then until his death in the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

where he was ''maestro di cappella

(, also , ) from German ''Kapelle'' (chapel) and ''Meister'' (master)'','' literally "master of the chapel choir" designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term ha ...

'' at the basilica of San Marco

San Marco is one of the six sestieri of Venice, lying in the heart of the city as the main place of Venice. San Marco also includes the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. Although the district includes Saint Mark's Square, that was never admin ...

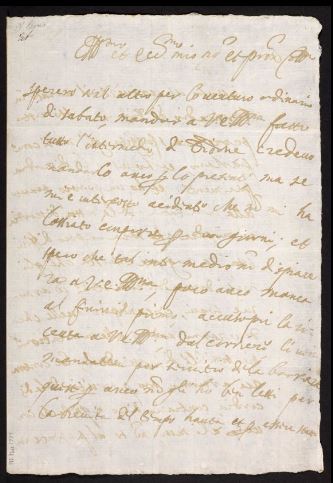

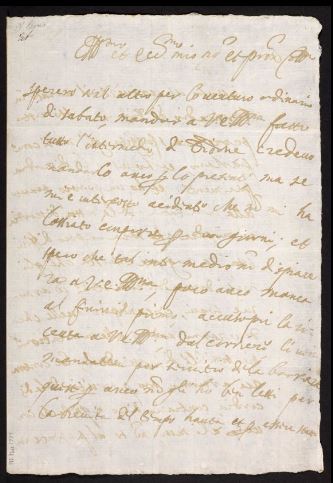

. His surviving letters give insight into the life of a professional musician in Italy of the period, including problems of income, patronage and politics.

Much of Monteverdi's output, including many stage works, has been lost. His surviving music includes nine books of madrigals, large-scale religious works, such as his ''Vespro della Beata Vergine

''Vespro della Beata Vergine'' (''Vespers for the Blessed Virgin''), SV 206, is a musical setting by Claudio Monteverdi of the evening vespers on Marian feasts, scored for soloists, choirs, and orchestra. It is an ambitious work in scope and i ...

'' (''Vespers for the Blessed Virgin'') of 1610, and three complete operas. His opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libr ...

''L'Orfeo

''L'Orfeo'' ( SV 318) (), sometimes called ''La favola d'Orfeo'' , is a late Renaissance/early Baroque ''favola in musica'', or opera, by Claudio Monteverdi, with a libretto by Alessandro Striggio. It is based on the Greek legend of Orpheus, and ...

'' (1607) is the earliest of the genre still widely performed; towards the end of his life he wrote works for Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, including '' Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria'' and ''L'incoronazione di Poppea

''L'incoronazione di Poppea'' ( SV 308, ''The Coronation of Poppaea'') is an Italian opera by Claudio Monteverdi. It was Monteverdi's last opera, with a libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, and was first performed at the Teatro Santi Giovanni ...

''.

While he worked extensively in the tradition of earlier Renaissance polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, ...

, as evidenced in his madrigals, he undertook great developments in form and melody, and began to employ the basso continuo technique, distinctive of the Baroque. No stranger to controversy, he defended his sometimes novel techniques as elements of a ''seconda pratica Seconda pratica, Italian for "second practice", is the counterpart to prima pratica and is sometimes referred to as Stile moderno. The term "Seconda pratica" first appeared in 1603 in Giovanni Artusi's book ''Seconda Parte dell'Artusi, overo Delle i ...

'', contrasting with the more orthodox earlier style which he termed the ''prima pratica

''Stile antico'' (literally "ancient style", ), is a term describing a manner of musical composition from the sixteenth century onwards that was historically conscious, as opposed to ''stile moderno'', which adhered to more modern trends. ''Prima ...

''. Largely forgotten during the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries, his works enjoyed a rediscovery around the beginning of the twentieth century. He is now established both as a significant influence in European musical history and as a composer whose works are regularly performed and recorded.

Life

Cremona: 1567–1591

Monteverdi was baptised in the church of SS Nazaro e Celso, Cremona, on 15 May 1567. The register records his name as "Claudio Zuan Antonio" the son of "Messer Baldasar Mondeverdo".Fabbri (2007), p. 6 He was the first child of the apothecary Baldassare Monteverdi and his first wife Maddalena (née Zignani); they had married early the previous year. Claudio's brotherGiulio Cesare Monteverdi

Giulio Cesare Monteverdi (1573–1630/31) was an Italian composer and organist. He was the younger brother of Claudio Monteverdi.

He entered the service of the Duke of Mantua in 1602, but was dismissed in 1612. He then worked in Crema and becam ...

(b. 1573) was also to become a musician; there were two other brothers and two sisters from Baldassare's marriage to Maddalena and his subsequent marriage in 1576 or 1577.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §1 "Cremona" Cremona was close to the border of the Republic of Venice, and not far from the lands controlled by the Duchy of Mantua, in both of which states Monteverdi was later to establish his career.

There is no clear record of Monteverdi's early musical training, or evidence that (as is sometimes claimed) he was a member of the Cathedral choir or studied at Cremona University. Monteverdi's first published work, a set of

There is no clear record of Monteverdi's early musical training, or evidence that (as is sometimes claimed) he was a member of the Cathedral choir or studied at Cremona University. Monteverdi's first published work, a set of motets

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Marga ...

, '' (Sacred Songs)'' for three voices, was issued in Venice in 1582, when he was only fifteen years old. In this, and his other initial publications, he describes himself as the pupil of Marc'Antonio Ingegneri, who was from 1581 (and possibly from 1576) to 1592 the ''maestro di cappella

(, also , ) from German ''Kapelle'' (chapel) and ''Meister'' (master)'','' literally "master of the chapel choir" designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term ha ...

'' at Cremona Cathedral

Cremona Cathedral ( it, Duomo di Cremona, ''Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta''), dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, is a Catholic cathedral in Cremona, Lombardy, northern Italy. It is the seat of the Bishop of Cremona. Its ...

. The musicologist Tim Carter deduces that Ingegneri "gave him a solid grounding in counterpoint and composition", and that Monteverdi would also have studied playing instruments of the viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

family and singing.Whenham (2007) "Chronology", p. xv.Arnold (1980a), p. 515

Monteverdi's first publications also give evidence of his connections beyond Cremona, even in his early years. His second published work, ''Madrigali spirituali'' (Spiritual Madrigals, 1583), was printed at Brescia. His next works (his first published secular compositions) were sets of five-part madrigals, according to his biographer Paolo Fabbri Paolo Fabbri may refer to:

* Paolo Fabbri (musicologist) (born 1948), Italian musicologist

* Paolo Fabbri (semiotician) (1939–2020), Italian semiotician

* Paolo Fabbri, character in ''L'isola di Montecristo'' played by Claudio Gora

Claudio G ...

: "the inevitable proving ground for any composer of the second half of the sixteenth century ... the secular genre ''par excellence''". The first book of madrigals (Venice, 1587) was dedicated to Count Marco Verità of Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

; the second book of madrigals (Venice, 1590) was dedicated to the President of the Senate of Milan, Giacomo Ricardi, for whom he had played the viola da braccio in 1587.

Mantua: 1591–1613

Court musician

In the dedication of his second book of madrigals, Monteverdi had described himself as a player of the ''vivuola'' (which could mean either

In the dedication of his second book of madrigals, Monteverdi had described himself as a player of the ''vivuola'' (which could mean either viola da gamba

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitch ...

or viola da braccio). In 1590 or 1591 he entered the service of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga

Vincenzo Ι Gonzaga (21 September 1562 – 9 February 1612) was ruler of the Duchy of Mantua and the Duchy of Montferrat from 1587 to 1612.

Biography

Vincenzo was the only son of Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, and Archduchess Eleanor of Aust ...

of Mantua; he recalled in his dedication to the Duke of his third book of madrigals (Venice, 1592) that "the most noble exercise of the ''vivuola'' opened to me the fortunate way into your service." In the same dedication he compares his instrumental playing to "flowers" and his compositions as "fruit" which as it matures "can more worthily and more perfectly serve you", indicating his intentions to establish himself as a composer.

Duke Vincenzo was keen to establish his court as a musical centre, and sought to recruit leading musicians. When Monteverdi arrived in Mantua, the ''maestro di capella'' at the court was the Flemish musician Giaches de Wert

Giaches de Wert (also Jacques/Jaches de Wert, Giaches de Vuert; 1535 – 6 May 1596) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the late Renaissance, active in Italy. Intimately connected with the progressive musical center of Ferrara, he was one of the lea ...

. Other notable musicians at the court during this period included the composer and violinist Salomone Rossi

Salamone Rossi or Salomone Rossi ( he, סלומונה רוסי or שלמה מן האדומים) (Salamon, Schlomo; de' Rossi) (ca. 1570 – 1630) was an Italian Jewish violinist and composer. He was a transitional figure between the late Ita ...

, Rossi's sister, the singer Madama Europa, and Francesco Rasi

Francesco Rasi (14 May 1574 – 30 November 1621) was an Italian composer, singer (tenor), chitarrone player, and poet.

Rasi was born in Arezzo. He studied at the University of Pisa and in 1594 he was studying with Giulio Caccini. He may have bee ...

. Monteverdi married the court singer Claudia de Cattaneis in 1599; they were to have three children, two sons (Francesco, b. 1601 and Massimiliano, b. 1604), and a daughter who died soon after birth in 1603. Monteverdi's brother Giulio Cesare joined the court musicians in 1602.Arnold (1980b), pp. 534–535

When Wert died in 1596, his post was given to Benedetto Pallavicino Benedetto Pallavicino (c. 1551 – 26 November 1601) was an Italian composer and organist of the late Renaissance. A prolific composer of madrigals, he was resident at the Gonzaga court of Mantua in the 1590s, where he was a close associate of Gia ...

, but Monteverdi was clearly highly regarded by Vincenzo and accompanied him on his military campaigns in Hungary (1595) and also on a visit to Flanders in 1599. Here at the town of Spa he is reported by his brother Giulio Cesare as encountering, and bringing back to Italy, the ''canto alla francese''. (The meaning of this, literally "song in the French style", is debatable, but may refer to the French-influenced poetry of Gabriello Chiabrera, some of which was set by Monteverdi in his ''Scherzi musicali'', and which departs from the traditional Italian style of lines of 9 or 11 syllables). Monteverdi may possibly have been a member of Vincenzo's entourage at Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

in 1600 for the marriage of Maria de' Medici and Henry IV of France, at which celebrations Jacopo Peri's opera '' Euridice'' (the earliest surviving opera) was premiered. On the death of Pallavicino in 1601, Monteverdi was confirmed as the new ''maestro di capella''.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §2 "Mantua"

Artusi controversy and ''seconda pratica''

At the turn of the 17th century, Monteverdi found himself the target of musical controversy. The influential Bolognese theorist

At the turn of the 17th century, Monteverdi found himself the target of musical controversy. The influential Bolognese theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi

Giovanni Maria Artusi (c. 154018 August 1613) was an Italian music theory, theorist, composer, and writer.

Artusi fiercely condemned the new musical innovations that defined the early Baroque music, Baroque style developing around 1600 in his tre ...

attacked Monteverdi's music (without naming the composer) in his work ''L'Artusi, overo Delle imperfettioni della moderna musica (Artusi, or On the imperfections of modern music)'' of 1600, followed by a sequel in 1603. Artusi cited extracts from Monteverdi's works not yet published (they later formed parts of his fourth and fifth books of madrigals of 1603 and 1605), condemning their use of harmony and their innovations in use of musical modes, compared to orthodox polyphonic practice of the sixteenth century. Artusi attempted to correspond with Monteverdi on these issues; the composer refused to respond, but found a champion in a pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

ous supporter, "L'Ottuso Academico" ("The Obtuse Academic"). Eventually Monteverdi replied in the preface to the fifth book of madrigals that his duties at court prevented him from a detailed reply; but in a note to "the studious reader", he claimed that he would shortly publish a response, ''Seconda Pratica, overo Perfettione della Moderna Musica (The Second Style, or Perfection of Modern Music).'' This work never appeared, but a later publication by Claudio's brother Giulio Cesare made it clear that the ''seconda pratica Seconda pratica, Italian for "second practice", is the counterpart to prima pratica and is sometimes referred to as Stile moderno. The term "Seconda pratica" first appeared in 1603 in Giovanni Artusi's book ''Seconda Parte dell'Artusi, overo Delle i ...

'' which Monteverdi defended was not seen by him as a radical change or his own invention, but was an evolution from previous styles (''prima pratica

''Stile antico'' (literally "ancient style", ), is a term describing a manner of musical composition from the sixteenth century onwards that was historically conscious, as opposed to ''stile moderno'', which adhered to more modern trends. ''Prima ...

'') which was complementary to them.

This debate seems in any case to have raised the composer's profile, leading to reprints of his earlier books of madrigals. Some of his madrigals were published in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

in 1605 and 1606, and the poet Tommaso Stigliani

Tommaso Stigliani (1573–1651) was an Italians, Italian poet, literary critic, and writer.

Biography

He was born in Matera, and educated in Naples where he met with the poets Torquato Tasso and Giambattista Marino. With the latter, Stigliani sta ...

(1573–1651) published a eulogy of him in his 1605 poem "O sirene de' fiumi". The composer of madrigal comedies and theorist Adriano Banchieri

Adriano Banchieri (Bologna, 3 September 1568 – Bologna, 1634) was an Italian composer, music theorist, organist and poet of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He founded the Accademia dei Floridi in Bologna.

Biography

He was bo ...

wrote in 1609: "I must not neglect to mention the most noble of composers, Monteverdi ... his expressive qualities are truly deserving of the highest commendation, and we find in them countless examples of matchless declamation ... enhanced by comparable harmonies." The modern music historian Massimo Ossi has placed the Artusi issue in the context of Monteverdi's artistic development: "If the controversy seems to define Monteverdi's historical position, it also seems to have been about stylistic developments that by 1600 Monteverdi had already outgrown".

The non-appearance of Monteverdi's promised explanatory treatise may have been a deliberate ploy, since by 1608, by Monteverdi's reckoning, Artusi had become fully reconciled to modern trends in music, and the ''seconda pratica'' was by then well established; Monteverdi had no need to revisit the issue. On the other hand, letters to Giovanni Battista Doni

Giovanni Battista Doni (bap. 13 March 1595 – 1647) was an Italian musicologist and humanist who made an extensive study of ancient music. He is known, among other works, for having renamed the note "Ut" to "Do" in solfège.

In his day, he was ...

of 1632 show that Monteverdi was still preparing a defence of the ''seconda practica'', in a treatise entitled ''Melodia''; he may still have been working on this at the time of his death ten years later.

Opera, conflict and departure

In 1606 Vincenzo's heir Francesco commissioned from Monteverdi the opera ''L'Orfeo

''L'Orfeo'' ( SV 318) (), sometimes called ''La favola d'Orfeo'' , is a late Renaissance/early Baroque ''favola in musica'', or opera, by Claudio Monteverdi, with a libretto by Alessandro Striggio. It is based on the Greek legend of Orpheus, and ...

'', to a libretto by Alessandro Striggio

Alessandro Striggio (c. 1536/1537 – 29 February 1592) was an Italian composer, instrumentalist and diplomat of the Renaissance. He composed numerous madrigals as well as dramatic music, and by combining the two, became the inventor of madrigal c ...

, for the Carnival season of 1607. It was given two performances in February and March 1607; the singers included, in the title role, Rasi, who had sung in the first performance of ''Euridice'' witnessed by Vincenzo in 1600. This was followed in 1608 by the opera '' L'Arianna'' (libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini), intended for the celebration of the marriage of Francesco to Margherita of Savoy

Margherita of Savoy (''Margherita Maria Teresa Giovanna''; 20 November 1851 – 4 January 1926) was Queen of Italy by marriage to Umberto I.

Life

Early life

Margherita was born to Prince Ferdinand of Savoy, Duke of Genoa and Princess Elisabe ...

. All the music for this opera is lost apart from ''Ariadne's Lament'', which became extremely popular. To this period also belongs the ballet entertainment '' Il ballo delle ingrate''.

The strain of the hard work Monteverdi had been putting into these and other compositions was exacerbated by personal tragedies. His wife died in September 1607 and the young singer Caterina Martinelli, intended for the title role of ''Arianna'', died of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

in March 1608. Monteverdi also resented his increasingly poor financial treatment by the Gonzagas. He retired to Cremona in 1608 to convalesce, and wrote a bitter letter to Vincenzo's minister Annibale Chieppio in November of that year seeking (unsuccessfully) "an honourable dismissal". Although the Duke increased Monteverdi's salary and pension, and Monteverdi returned to continue his work at the court, he began to seek patronage elsewhere. After publishing his Vespers

Vespers is a service of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic (both Latin and Eastern), Lutheran, and Anglican liturgies. The word for this fixed prayer time comes from the Latin , meanin ...

in 1610, which were dedicated to Pope Paul V

Pope Paul V ( la, Paulus V; it, Paolo V) (17 September 1550 – 28 January 1621), born Camillo Borghese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 16 May 1605 to his death in January 1621. In 1611, he honored ...

, he visited Rome, ostensibly hoping to place his son Francesco at a seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy ...

, but apparently also seeking alternative employment. In the same year he may also have visited Venice, where a large collection of his church music was being printed, with a similar intention.Arnold (1980a), p. 516

Duke Vincenzo died on 18 February 1612. When Francesco succeeded him, court intrigues and cost-cutting led to the dismissal of Monteverdi and his brother Giulio Cesare, who both returned, almost penniless, to Cremona. Despite Francesco's own death from smallpox in December 1612, Monteverdi was unable to return to favour with his successor, his brother Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga. In 1613, following the death of Giulio Cesare Martinengo, Monteverdi auditioned for his post as ''maestro'' at the basilica of San Marco in Venice, for which he submitted music for a Mass. He was appointed in August 1613, and given 50 ducats for his expenses (of which he was robbed, together with his other belongings, by highwaymen at Sanguinetto

Sanguinetto is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Verona in the Italian region Veneto, located about southwest of Venice and about southeast of Verona. As of 31 December 2004, it had a population of 4,009 and an area of .All demograp ...

on his return to Cremona).Stevens (1995), pp. 83–85

Venice: 1613–1643

Maturity: 1613–1630

Martinengo had been ill for some time before his death and had left the music of San Marco in a fragile state. The choir had been neglected and the administration overlooked. When Monteverdi arrived to take up his post, his principal responsibility was to recruit, train, discipline and manage the musicians of San Marco (the ''capella''), who amounted to about 30 singers and six instrumentalists; the numbers could be increased for major events.Fabbri (2007), pp. 128–129 Among the recruits to the choir was Francesco Cavalli, who joined in 1616 at the age of 14; he was to remain connected with San Marco throughout his life, and was to develop a close association with Monteverdi.Walker and Alm (n.d.) Monteverdi also sought to expand the repertory, including not only the traditional '' a cappella'' repertoire of Roman and Flemish composers, but also examples of the modern style which he favoured, including the use of continuo and other instruments. Apart from this he was of course expected to compose music for all the major feasts of the church. This included a new

Martinengo had been ill for some time before his death and had left the music of San Marco in a fragile state. The choir had been neglected and the administration overlooked. When Monteverdi arrived to take up his post, his principal responsibility was to recruit, train, discipline and manage the musicians of San Marco (the ''capella''), who amounted to about 30 singers and six instrumentalists; the numbers could be increased for major events.Fabbri (2007), pp. 128–129 Among the recruits to the choir was Francesco Cavalli, who joined in 1616 at the age of 14; he was to remain connected with San Marco throughout his life, and was to develop a close association with Monteverdi.Walker and Alm (n.d.) Monteverdi also sought to expand the repertory, including not only the traditional '' a cappella'' repertoire of Roman and Flemish composers, but also examples of the modern style which he favoured, including the use of continuo and other instruments. Apart from this he was of course expected to compose music for all the major feasts of the church. This included a new mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

each year for Holy Cross Day and Christmas Eve, cantatas in honour of the Venetian Doge

A doge ( , ; plural dogi or doges) was an elected lord and head of state in several Italian city-states, notably Venice and Genoa, during the medieval and renaissance periods. Such states are referred to as " crowned republics".

Etymology

The ...

, and numerous other works (many of which are lost). Monteverdi was also free to obtain income by providing music for other Venetian churches and for other patrons, and was frequently commissioned to provide music for state banquets. The Procurators of San Marco, to whom Monteverdi was directly responsible, showed their satisfaction with his work in 1616 by raising his annual salary from 300 ducats to 400.

The relative freedom which the Republic of Venice afforded him, compared to the problems of court politics in Mantua, are reflected in Monteverdi's letters to Striggio, particularly his letter of 13 March 1620, when he rejects an invitation to return to Mantua, extolling his present position and finances in Venice, and referring to the pension which Mantua still owes him. Nonetheless, remaining a Mantuan citizen, he accepted commissions from the new Duke Ferdinando, who had formally renounced his position as Cardinal in 1616 to take on the duties of state. These included the '' balli'' ''Tirsi e Clori'' (1616) and ''Apollo'' (1620), an opera '' Andromeda'' (1620) and an ''intermedio

The intermedio (also intromessa, introdutto, tramessa, tramezzo, intermezzo, intermedii), in the Italian Renaissance, was a theatrical performance or spectacle with music and often dance, which was performed between the acts of a play to celeb ...

'', '' Le nozze di Tetide'', for the marriage of Ferdinando with Caterina de' Medici (1617). Most of these compositions were extensively delayed in creation – partly, as shown by surviving correspondence, through the composer's unwillingness to prioritise them, and partly because of constant changes in the court's requirements. They are now lost, apart from ''Tirsi e Clori'', which was included in the seventh book of madrigals (published 1619) and dedicated to the Duchess Caterina, for which the composer received a pearl necklace from the Duchess. A subsequent major commission, the opera ''La finta pazza Licori

The Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), in addition to a large output of church music and madrigals, wrote prolifically for the stage. His theatrical works were written between 1604 and 1643 and included operas, of which three—' ...

'', to a libretto by Giulio Strozzi

Giulio Strozzi (1583 - 31 March 1652) was a Venetian poet and libretto writer. His libretti were put to music by composers like Claudio Monteverdi, Francesco Cavalli, Francesco Manelli, and Francesco Sacrati. He sometimes used the pseudonym Luigi ...

, was completed for Fernando's successor Vincenzo II, who succeeded to the dukedom in 1626. Because of the latter's illness (he died in 1627), it was never performed, and it is now also lost.

Monteverdi also received commissions from other Italian states and from their communities in Venice. These included, for the Milanese community in 1620, music for the Feast of

Monteverdi also received commissions from other Italian states and from their communities in Venice. These included, for the Milanese community in 1620, music for the Feast of St. Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo ( it, Carlo Borromeo; la, Carolus Borromeus; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was the Archdiocese of Milan, Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584 and a Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was a lead ...

, and for the Florentine community a Requiem Mass for Cosimo II de' Medici

Cosimo II de' Medici (12 May 1590 – 28 February 1621) was Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1609 until his death. He was the elder son of Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Christina of Lorraine.

For the majority of his twelve-ye ...

(1621). Monteverdi acted on behalf of Paolo Giordano II, Duke of Bracciano, to arrange publication of works by the Cremona musician Francesco Petratti. Among Monteverdi's private Venetian patrons was the nobleman Girolamo Mocenigo, at whose home was premiered in 1624 the dramatic entertainment '' Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda'' based on an episode from Torquato Tasso's ''La Gerusalemme liberata

''Jerusalem Delivered'', also known as ''The Liberation of Jerusalem'' ( it, La Gerusalemme liberata ; ), is an epic poem by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso, first published in 1581, that tells a largely mythified version of the First Crusade i ...

''. In 1627 Monteverdi received a major commission from Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, for a series of works, and gained leave from the Procurators to spend time there during 1627 and 1628.

Monteverdi's musical direction received the attention of foreign visitors. The Dutch diplomat and musician Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist Ch ...

, attending a Vespers service at the church of SS. Giovanni e Lucia, wrote that he "heard the most perfect music I had ever heard in my life. It was directed by the most famous Claudio Monteverdi ... who was also the composer and was accompanied by four theorbos, two cornett

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is an early wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. It was used in what are now called alta capellas or wind ensembles. It is not to be confused wi ...

os, two bassoons, one ''basso de viola'' of huge size, organs and other instruments ...". Monteverdi wrote a mass, and provided other musical entertainment, for the visit to Venice in 1625 of the Crown Prince Władysław of Poland, who may have sought to revive attempts made a few years previously to lure Monteverdi to Warsaw. He also provided chamber music for Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg

Wolfgang Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg (4 November 1578 in Neuburg an der Donau – 14 September 1653 in Düsseldorf) was a German Prince. He was Count palatine of Neuburg and Duke of Jülich and Berg.

Life

Wolfgang Wilhelm's parents were Ph ...

, when the latter was paying an incognito visit to Venice in July 1625.

Correspondence of Monteverdi in 1625 and 1626 with the Mantuan courtier Ercole Marigliani reveals an interest in alchemy, which apparently Monteverdi had taken up as a hobby. He discusses experiments to transform lead into gold, the problems of obtaining mercury, and mentions commissioning special vessels for his experiments from the glassworks at Murano.

Despite his generally satisfactory situation in Venice, Monteverdi experienced personal problems from time to time. He was on one occasion – probably because of his wide network of contacts – the subject of an anonymous denunciation to the Venetian authorities alleging that he supported the Habsburgs. He was also subject to anxieties about his children. His son Francesco, while a student of law at Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

in 1619, was spending in Monteverdi's opinion too much time with music, and he, therefore, moved him to the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in continu ...

. This did not have the required result, and it seems that Monteverdi resigned himself to Francesco having a musical career – he joined the choir of San Marco in 1623. His other son Massimiliano, who graduated in medicine, was arrested by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

in Mantua in 1627 for reading forbidden literature. Monteverdi was obliged to sell the necklace he had received from Duchess Caterina to pay for his son's (eventually successful) defence. Monteverdi wrote at the time to Striggio seeking his help, and fearing that Massimiliano might be subject to torture; it seems that Striggio's intervention was helpful. Money worries at this time also led Monteverdi to visit Cremona to secure for himself a church canonry

A canon (from the Latin , itself derived from the Greek , , "relating to a rule", "regular") is a member of certain bodies in subject to an ecclesiastical rule.

Originally, a canon was a cleric living with others in a clergy house or, later, i ...

.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §3 "Venice"

Pause and priesthood: 1630–1637

A series of disturbing events troubled Monteverdi's world in the period around 1630. Mantua was invaded by Habsburg armies in 1630, who besieged the plague-stricken town, and after its fall in July looted its treasures, and dispersed the artistic community. The plague was carried to Mantua's ally Venice by an embassy led by Monteverdi's confidante Striggio, and over a period of 16 months led to over 45,000 deaths, leaving Venice's population in 1633 at just above 100,000, the lowest level for about 150 years. Among the plague victims was Monteverdi's assistant at San Marco, and a notable composer in his own right,Alessandro Grandi

Alessandro Grandi (1590 – after June 1630, but in that year) was a northern Italian composer of the early Baroque era, writing in the new concertato style. He was one of the most inventive, influential, and popular composers of the time, proba ...

. The plague and the after-effects of war had an inevitable deleterious effect on the economy and artistic life of Venice.Whenham (2007) "Chronology", p. xxArnold (1980c), p. 617. Monteverdi's younger brother Giulio Cesare also died at this time, probably from the plague.

By this time Monteverdi was in his sixties, and his rate of composition seems to have slowed down. He had written a setting of Strozzi's ''Proserpina rapita

Proserpina ( , ) or Proserpine ( ) is an ancient Roman goddess whose iconography, functions and myths are virtually identical to those of Greek Persephone. Proserpina replaced or was combined with the ancient Roman fertility goddess Libera, whose ...

( The Abduction of Proserpina)'', now lost except for one vocal trio, for a Mocenigo wedding in 1630, and produced a Mass for deliverance from the plague for San Marco which was performed in November 1631. His set of ''Scherzi musicali'' was published in Venice in 1632. In 1631, Monteverdi was admitted to the tonsure, and was ordained deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

, and later priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

, in 1632. Although these ceremonies took place in Venice, he was nominated as a member of Diocese of Cremona; this may imply that he intended to retire there.

Late flowering: 1637–1643

The opening of the opera house of San Cassiano in 1637, the first public opera house in Europe, stimulated the city's musical life and coincided with a new burst of the composer's activity. The year 1638 saw the publication of Monteverdi's eighth book of madrigals and a revision of the ''Ballo delle ingrate''. The eighth book contains a ''ballo'', "Volgendi il ciel", which may have been composed for the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand III, to whom the book is dedicated. The years 1640–1641 saw the publication of the extensive collection of church music, ''Selva morale e spirituale

''Selva morale e spirituale'' (Stattkus-Verzeichnis, SV 252–288) is the short title of a collection of sacred music by the Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi, published in Venice in 1640 and 1641. The title translates to "Moral and Spiritual F ...

''. Among other commissions, Monteverdi wrote music in 1637 and 1638 for Strozzi's "Accademia degli Unisoni" in Venice, and in 1641 a ballet, ''La vittoria d'Amore'', for the court of Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

.Wenham (2007) "Chronology", p. xxi.

Monteverdi was still not entirely free from his responsibilities for the musicians at San Marco. He wrote to complain about one of his singers to the Procurators, on 9 June 1637: "I, Claudio Monteverdi ... come humbly ... to set forth to you how Domenicato Aldegati ... a bass, yesterday morning ... at the time of the greatest concourse of people ... spoke these exact words ...'The Director of Music comes from a brood of cut-throat bastards, a thieving, fucking, he-goat ... and I shit on him and whoever protects him ....

Monteverdi's contribution to opera at this period is notable. He revised his earlier opera ''L'Arianna'' in 1640 and wrote three new works for the commercial stage, ''Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland'', 1640, first performed in Bologna with Venetian singers), '' Le nozze d'Enea e Lavinia (The Marriage of Aeneas and Lavinia'', 1641, music now lost), and ''L'incoronazione di Poppea

''L'incoronazione di Poppea'' ( SV 308, ''The Coronation of Poppaea'') is an Italian opera by Claudio Monteverdi. It was Monteverdi's last opera, with a libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, and was first performed at the Teatro Santi Giovanni ...

'' (''The Coronation of Poppea

Poppaea Sabina (AD 30 – 65), also known as Ollia, was a Roman empress as the second wife of the Roman emperor, Emperor Nero. She had also been wife to the future emperor Otho. The historians of Classical antiquity, antiquity describe her as a ...

'', 1643). The introduction to the printed scenario of ''Le nozze d'Enea'', by an unknown author, acknowledges that Monteverdi is to be credited for the rebirth of theatrical music and that "he will be sighed for in later ages, for his compositions will surely outlive the ravages of time."

In his last surviving letter (20 August 1643), Monteverdi, already ill, was still hoping for the settlement of the long-disputed pension from Mantua, and asked the Doge of Venice to intervene on his behalf. He died in Venice on 29 November 1643, after paying a brief visit to Cremona, and is buried in the Church of the Frari. He was survived by his sons; Masimilliano died in 1661, Francesco after 1677.

Music

Background: Renaissance to Baroque

There is a consensus among music historians that a period extending from the mid-15th century to around 1625, characterised in

There is a consensus among music historians that a period extending from the mid-15th century to around 1625, characterised in Lewis Lockwood

Lewis H. Lockwood (born December 16, 1930) is an American musicologist whose main fields are the music of the Italian Renaissance and the life and work of Ludwig van Beethoven. Joseph Kerman described him as "a leading musical scholar of the postw ...

's phrase by "substantial unity of outlook and language", should be identified as the period of " Renaissance music".Lockwood (n.d.) Musical literature has also defined the succeeding period (covering music from approximately 1580 to 1750) as the era of " Baroque music".Palisca (n.d.) It is in the late-16th to early-17th-century overlap of these periods that much of Monteverdi's creativity flourished; he stands as a transitional figure between the Renaissance and the Baroque.

In the Renaissance era, music had developed as a formal discipline, a "pure science of relationships" in the words of Lockwood. In the Baroque era it became a form of aesthetic expression, increasingly used to adorn religious, social and festive celebrations in which, in accordance with Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's ideal, the music was subordinated to the text.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §4 "Theoretical and aesthetic basis of works" Solo singing with instrumental accompaniment, or monody, acquired greater significance towards the end of the 16th century, replacing polyphony as the principal means of dramatic music expression. This was the changing world in which Monteverdi was active. Percy Scholes

Percy Alfred Scholes PhD OBE (24 July 1877 – 31 July 1958) (pronounced ''skolz'') was an English musician, journalist and prolific writer, whose best-known achievement was his compilation of the first edition of ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' ...

in his ''Oxford Companion to Music

''The Oxford Companion to Music'' is a music reference book in the series of Oxford Companions produced by the Oxford University Press. It was originally conceived and written by Percy Scholes and published in 1938. Since then, it has underg ...

'' describes the "new music" thus: " omposersdiscarded the choral polyphony of the madrigal style as barbaric, and set dialogue or soliloquy for single voices, imitating more or less the inflexions of speech and accompanying the voice by playing mere supporting chords. Short choruses were interspersed, but they too were homophonic

In music, homophony (;, Greek: ὁμόφωνος, ''homóphōnos'', from ὁμός, ''homós'', "same" and φωνή, ''phōnē'', "sound, tone") is a texture in which a primary part is supported by one or more additional strands that flesh ...

rather than polyphonic."

Novice years: Madrigal books 1 and 2

Ingegneri, Monteverdi's first tutor, was a master of the '' musica reservata'' vocal style, which involved the use of chromatic progressions and

Ingegneri, Monteverdi's first tutor, was a master of the '' musica reservata'' vocal style, which involved the use of chromatic progressions and word-painting

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song's lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

Historical development

Tone painting of words ...

; Monteverdi's early compositions were grounded in this style. Ingegneri was a traditional Renaissance composer, "something of an anachronism", according to Arnold, but Monteverdi also studied the work of more "modern" composers such as Luca Marenzio

Luca Marenzio (also Marentio; October 18, 1553 or 1554 – August 22, 1599) was an Italian composer and singer of the late Renaissance.

He was one of the most renowned composers of madrigals, and wrote some of the most famous examples of the fo ...

, Luzzasco Luzzaschi

Luzzasco Luzzaschi (c. 1545 – 10 September 1607) was an Italian composer, organist, and teacher of the late Renaissance. He was born and died in Ferrara, and despite evidence of travels to Rome it is assumed that Luzzaschi spent the majority o ...

, and a little later, Giaches de Wert, from whom he would learn the art of expressing passion. He was a precocious and productive student, as indicated by his youthful publications of 1582–83. Mark Ringer

Mark Ringer (born December 8, 1959) American writer, theater and opera historian, director and actor. Ringer’s books include ''Electra and the Empty Urn: Metatheater and Role Playing in Sophocles'', a critical analysis of theatrical self-awaren ...

writes that "these teenaged efforts reveal palpable ambition matched with a convincing mastery of contemporary style", but at this stage they display their creator's competence rather than any striking originality.Ringer (2006), p. 4 Geoffrey Chew classifies them as "not in the most modern vein for the period", acceptable but out-of-date.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §7 "Early works" Chew rates the ''Canzonette'' collection of 1584 much more highly than the earlier juvenilia: "These brief three-voice pieces draw on the airy, modern style of the villanella

In music, a villanella (; plural villanelle) is a form of light Italian secular vocal music which originated in Italy just before the middle of the 16th century. It first appeared in Naples, and influenced the later canzonetta, and from there also ...

s of Marenzio, rawing ona substantial vocabulary of text-related madrigalisms".

The canzonetta

In music, a canzonetta (; pl. canzonette, canzonetti or canzonettas) is a popular Italian secular vocal composition that originated around 1560. Earlier versions were somewhat like a madrigal but lighter in style—but by the 18th century, especial ...

form was much used by composers of the day as a technical exercise, and is a prominent element in Monteverdi's first book of madrigals published in 1587. In this book, the playful, pastoral settings again reflect the style of Marenzio, while Luzzaschi's influence is evident in Monteverdi's use of dissonance. The second book (1590) begins with a setting modelled on Marenzio of a modern verse, Torquato Tasso's "Non si levav' ancor", and concludes with a text from 50 years earlier: Pietro Bembo's "Cantai un tempo". Monteverdi set the latter to music in an archaic style reminiscent of the long-dead Cipriano de Rore

Cipriano de Rore (occasionally Cypriano) (1515 or 1516 – between 11 and 20 September 1565) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance, active in Italy. Not only was he a central representative of the generation of Franco-Flemish compose ...

. Between them is "Ecco mormorar l'onde", strongly influenced by de Wert and hailed by Chew as the great masterpiece of the second book.

A thread common throughout these early works is Monteverdi's use of the technique of ''imitatio'', a general practice among composers of the period whereby material from earlier or contemporary composers was used as models for their own work. Monteverdi continued to use this procedure well beyond his apprentice years, a factor that in some critics' eyes has compromised his reputation for originality.

Madrigals 1590–1605: books 3, 4, 5

Monteverdi's first fifteen years of service in Mantua are bracketed by his publications of the third book of madrigals in 1592 and the fourth and fifth books in 1603 and 1605. Between 1592 and 1603 he made minor contributions to other anthologies.Bowers (2007), p. 58 How much he composed in this period is a matter of conjecture; his many duties in the Mantuan court may have limited his opportunities,Ossi (2007), p. 97 but several of the madrigals that he published in the fourth and fifth books were written and performed during the 1590s, some figuring prominently in the Artusi controversy. The third book shows strongly the increased influence of Wert,Carter and Chew (n.d.), §8 "Works from the Mantuan Years" by that time Monteverdi's direct superior as ''maestro de capella'' at Mantua. Two poets dominate the collection: Tasso, whose lyrical poetry had figured prominently in the second book but is here represented through the more epic, heroic verses from '' Gerusalemme liberata'', andGiovanni Battista Guarini

Giovanni Battista Guarini (10 December 1538 – 7 October 1612) was an Italian poet, dramatist, and diplomat.

Life

Guarini was born in Ferrara. On the termination of his studies at the universities of Pisa, Padua and Ferrara, he was appointed pr ...

, whose verses had appeared sporadically in Monteverdi's earlier publications, but form around half of the contents of the third book. Wert's influence is reflected in Monteverdi's forthrightly modern approach, and his expressive and chromatic settings of Tasso's verses. Of the Guarini settings, Chew writes: "The epigrammatic style ... closely matches a poetic and musical ideal of the period ... ndoften depends on strong, final cadential progressions, with or without the intensification provided by chains of suspended dissonances". Chew cites the setting of "Stracciami pur il core" as "a prime example of Monteverdi's irregular dissonance practice". Tasso and Guarini were both regular visitors to the Mantuan court; Monteverdi's association with them and his absorption of their ideas may have helped lay the foundations of his own approach to the musical dramas that he would create a decade later.Ossi (2007), p. 98

As the 1590s progressed, Monteverdi moved closer towards the form that he would identify in due course as the ''seconda pratica''. Claude V. Palisca quotes the madrigal ''Ohimè, se tanto amate'', published in the fourth book but written before 1600 – it is among the works attacked by Artusi – as a typical example of the composer's developing powers of invention. In this madrigal Monteverdi again departs from the established practice in the use of dissonance, by means of a vocal ornament Palisca describes as ''échappé''. Monteverdi's daring use of this device is, says Palisca, "like a forbidden pleasure". In this and in other settings the poet's images were supreme, even at the expense of musical consistency.

The fourth book includes madrigals to which Artusi objected on the grounds of their "modernism". However, Ossi describes it as "an anthology of disparate works firmly rooted in the 16th century",Ossi (2007), pp. 102–103 closer in nature to the third book than to the fifth. Besides Tasso and Guarini, Monteverdi set to music verses by Rinuccini, Maurizio Moro

Maurizio Moro (15??—16??) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, best known for his madrigal (music), madrigals.

Life

Very little is known about his early life. Probably born in Ferrara, he became presbyter (''"canonico"'') at the Congregazio ...

(''Sì ch'io vorrei morire'') and Ridolfo Arlotti (''Luci serene e chiare''). There is evidence of the composer's familiarity with the works of Carlo Gesualdo, and with composers of the school of Ferrara such as Luzzaschi; the book was dedicated to a Ferrarese musical society, the ''Accademici Intrepidi''.

The fifth book looks more to the future; for example, Monteverdi employs the '' concertato'' style with basso continuo (a device that was to become a typical feature in the emergent Baroque era), and includes a ''sinfonia'' (instrumental interlude) in the final piece. He presents his music through complex counterpoint and daring harmonies, although at times combining the expressive possibilities of the new music with traditional polyphony.

Aquilino Coppini drew much of the music for his sacred contrafacta

In vocal music, contrafactum (or contrafact, pl. contrafacta) is "the substitution of one text for another without substantial change to the music". The earliest known examples of this procedure (sometimes referred to as ''adaptation''), date back ...

of 1608 from Monteverdi's 3rd, 4th and 5th books of madrigals. In writing to a friend in 1609 Coppini commented that Monteverdi's pieces "require, during their performance, more flexible rests and bars that are not strictly regular, now pressing forward or abandoning themselves to slowing down ..In them there is a truly wondrous capacity for moving the affections".

Opera and sacred music: 1607–1612

In Monteverdi's final five years' service in Mantua he completed the operas ''L'Orfeo'' (1607) and ''L'Arianna'' (1608), and wrote quantities of sacred music, including the ''Messa in illo tempore'' (1610) and also the collection known as ''Vespro della Beata Vergine'' which is often referred to as "Monteverdi's ''Vespers''" (1610). He also published ''Scherzi musicale a tre voci'' (1607), settings of verses composed since 1599 and dedicated to the Gonzaga heir, Francesco. The vocal trio in the ''Scherzi'' comprises two sopranos and a bass, accompanied by simple instrumental ritornellos. According to Bowers the music "reflected the modesty of the prince's resources; it was, nevertheless, the earliest publication to associate voices and instruments in this particular way".''L'Orfeo''

The opera opens with a brief trumpet

The opera opens with a brief trumpet toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virtu ...

. The prologue of La musica (a figure representing music) is introduced with a ritornello by the strings, repeated often to represent the "power of music" – one of the earliest examples of an operatic leitmotif. Act 1 presents a pastoral idyll, the buoyant mood of which continues into Act 2. The confusion and grief which follow the news of Euridice's death are musically reflected by harsh dissonances and the juxtaposition of keys. The music remains in this vein until the act ends with the consoling sounds of the ritornello.

Act 3 is dominated by Orfeo's aria "Possente spirto e formidabil nume" by which he attempts to persuade Caronte to allow him to enter Hades. Monteverdi's vocal embellishments and virtuoso accompaniment provide what Tim Carter has described as "one of the most compelling visual and aural representations" in early opera. In Act 4 the warmth of Proserpina's singing on behalf of Orfeo is retained until Orfeo fatally "looks back".Harnoncourt (1969), pp. 24–25 The brief final act, which sees Orfeo's rescue and metamorphosis, is framed by the final appearance of the ritornello and by a lively moresca that brings the audience back to their everyday world.

Throughout the opera Monteverdi makes innovative use of polyphony, extending the rules beyond the conventions which composers normally observed in fidelity to Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

. He combines elements of the traditional 16th-century madrigal with the new monodic style where the text dominates the music and sinfonias and instrumental ritornellos illustrate the action.

''L'Arianna''

The music for this opera is lost except for the ''Lamento d'Arianna'', which was published in the sixth book in 1614 as a five-voice madrigal; a separate monodic version was published in 1623. In its operatic context the lament depicts Arianna's various emotional reactions to her abandonment: sorrow, anger, fear, self-pity, desolation and a sense of futility. Throughout, indignation and anger are punctuated by tenderness, until a descending line brings the piece to a quiet conclusion. The musicologistSuzanne Cusick

Suzanne G. Cusick (born 1954) is a music historian and musicologist living in and working in New York City, where she is a Professor of Music at the Faculty of Arts and Science at the New York University. Her specialties are the music of seventeen ...

writes that Monteverdi "creat dthe lament as a recognizable genre of vocal chamber music and as a standard scene in opera ... that would become crucial, almost genre-defining, to the full-scale public operas of 17th-century Venice". Cusick observes how Monteverdi is able to match in music the "rhetorical and syntactical gestures" in the text of Ottavio Rinuccini. The opening repeated words "Lasciatemi morire" (Let me die) are accompanied by a dominant seventh chord which Ringer describes as "an unforgettable chromatic stab of pain". Ringer suggests that the lament defines Monteverdi's innovative creativity in a manner similar to that in which the Prelude and the Liebestod in ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was comp ...

'' announced Wagner's discovery of new expressive frontiers.Ringer (2006), pp. 96–98

Rinuccini's full libretto, which has survived, was set in modern times by Alexander Goehr ('' Arianna'', 1995), including a version of Monteverdi's ''Lament''.

Vespers

The ''Vespro della Beata Vergine'', Monteverdi's first published sacred music since the ''Madrigali spirituali'' of 1583, consists of 14 components: an introductory versicle and response, five psalms interspersed with five "sacred concertos" (Monteverdi's term),Whenham (1997), pp. 16–17 a hymn, and two Magnificat settings. Collectively these pieces fulfil the requirements for a Vespers service on any feast day of the Virgin. Monteverdi employs many musical styles; the more traditional features, such as

The ''Vespro della Beata Vergine'', Monteverdi's first published sacred music since the ''Madrigali spirituali'' of 1583, consists of 14 components: an introductory versicle and response, five psalms interspersed with five "sacred concertos" (Monteverdi's term),Whenham (1997), pp. 16–17 a hymn, and two Magnificat settings. Collectively these pieces fulfil the requirements for a Vespers service on any feast day of the Virgin. Monteverdi employs many musical styles; the more traditional features, such as cantus firmus

In music, a ''cantus firmus'' ("fixed melody") is a pre-existing melody forming the basis of a polyphonic composition.

The plural of this Latin term is , although the corrupt form ''canti firmi'' (resulting from the grammatically incorrect tre ...

, falsobordone and Venetian canzone

Literally "song" in Italian, a ''canzone'' (, plural: ''canzoni''; cognate with English ''to chant'') is an Italian or Provençal song or ballad. It is also used to describe a type of lyric which resembles a madrigal. Sometimes a composition w ...

, are mixed with the latest madrigal style, including echo effects and chains of dissonances. Some of the musical features used are reminiscent of ''L'Orfeo'', written slightly earlier for similar instrumental and vocal forces.

In this work the "sacred concertos" fulfil the role of the antiphons

An antiphon (Greek language, Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christianity, Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are the Psalms. Their form was favored by St Ambrose ...

which divide the psalms in regular Vespers services. Their non-liturgical character has led writers to question whether they should be within the service, or indeed whether this was Monteverdi's intention. In some versions of Monteverdi's ''Vespers'' (for example, those of Denis Stevens

Denis William Stevens CBE (2 March 1922 – 1 April 2004) was a British musicologist specialising in early music, conductor, professor of music and radio producer.

Early years

He was born in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire and attended the Royal ...

) the concertos are replaced with antiphons associated with the Virgin, although John Whenham

John Whenham is an English musicologist and academic who specializes in early Italian baroque music. He earned both a Bachelor of Music and a Master of Music from the University of Nottingham, and a Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Oxfor ...

in his analysis of the work argues that the collection as a whole should be regarded as a single liturgical and artistic entity.

All the psalms, and the Magnificat, are based on melodically limited and repetitious Gregorian chant psalm tones, around which Monteverdi builds a range of innovative textures. This concertato style challenges the traditional cantus firmus,Kurtzman 2007, pp. 147–153 and is most evident in the "Sonata sopra Sancta Maria", written for eight string and wind instruments plus basso continuo, and a single soprano voice. Monteverdi uses modern rhythms, frequent metre changes and constantly varying textures; yet, according to John Eliot Gardiner

Sir John Eliot Gardiner (born 20 April 1943) is an English conductor, particularly known for his performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Life and career

Born in Fontmell Magna, Dorset, son of Rolf Gardiner and Marabel Hodgkin, Ga ...

, "for all the virtuosity of its instrumental writing and the evident care which has gone into the combinations of timbre", Monteverdi's chief concern was resolving the proper combination of words and music.

The actual musical ingredients of the Vespers were not novel to Mantua – concertato had been used by Lodovico Grossi da Viadana, a former choirmaster at the cathedral of Mantua, while the ''Sonata sopra'' had been anticipated by Archangelo Crotti

Archangelo Crotti, (first name sometimes spelled Arcangelo) was a composer and monk who was active in 1608 at Ferrara in Italy.

In 1608 he published, in Venice, his ''Primo libro de' concerti ecclesiastici (First book of church concerts)'' includ ...

in his ''Sancta Maria'' published in 1608. It is, writes Denis Arnold

Denis Midgley Arnold (Sheffield, 15 December 1926 – Budapest, 28 April 1986) was a British musicologist.

Biography

After being employed in the extramural department of Queen's University, Belfast, he became a Lecturer in Music at the Univ ...

, Monteverdi's mixture of the various elements that makes the music unique. Arnold adds that the Vespers achieved fame and popularity only after their 20th-century rediscovery; they were not particularly regarded in Monteverdi's time.Arnold and Fortune (1968), pp. 123–124

Madrigals 1614–1638: books 6, 7 and 8

Sixth book

During his years in Venice Monteverdi published his sixth (1614), seventh (1619) and eighth (1638) books of madrigals. The sixth book consists of works written before the composer's departure from Mantua.Hans Redlich

Hans Ferdinand Redlich (11 February 1903 – 27 November 1968) was an Austrian musicologist, writer, conductor and composer who, due to political disruption by the Nazi Party, lived and worked in Britain from 1939 until his death nearly thirty yea ...

sees it as a transitional work, containing Monteverdi's last madrigal compositions in the manner of the ''prima pratica'', together with music which is typical of the new style of expression which Monteverdi had displayed in the dramatic works of 1607–08. The central theme of the collection is loss; the best-known work is the five-voice version of the ''Lamento d'Arianna'', which, says Massimo Ossi, gives "an object lesson in the close relationship between monodic recitative and counterpoint".Ossi (2007), pp. 107–108 The book contains Monteverdi's first settings of verses by Giambattista Marino, and two settings of Petrarch which Ossi considers the most extraordinary pieces in the volume, providing some "stunning musical moments".

Seventh book

While Monteverdi had looked backwards in the sixth book, he moved forward in the seventh book from the traditional concept of the madrigal, and from monody, in favour of chamber duets. There are exceptions, such the two solo ''lettere amorose'' (love letters) "Se i languidi miei sguardi" and "Se pur destina e vole", written to be performed ''genere rapresentativo'' – acted as well as sung. Of the duets which are the main features of the volume, Chew highlights "Ohimé, dov'è il mio ben, dov'è il mio core", aromanesca

Romanesca is a melodic-harmonic formula popular from the mid–16th to early–17th centuries that was used as an aria formula for singing poetry and as a subject for instrumental variation. The pattern, which is found in an endless collection of ...

in which two high voices express dissonances above a repetitive bass pattern.Carter and Chew (n.d.), §9 "Works from the Venetian Years" The book also contains large-scale ensemble works, and the ballet ''Tirsi e Clori''. This was the height of Monteverdi's "Marino period"; six of the pieces in the book are settings of the poet's verses. As Carter puts it, Monteverdi "embraced Marino's madrigalian kisses and love-bites with ... the enthusiasm typical of the period".Carter (2007) "The Venetian secular music", pp, 183–184 Some commentators have opined that the composer should have had better poetic taste.

Eighth book