Mongolia (1911–24) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The new government under Bogd Khan tried to seek international recognition, particularly from the Russian government. The

The new government under Bogd Khan tried to seek international recognition, particularly from the Russian government. The  While these efforts at obtaining international recognition continued, the Mongols and Russians were negotiating. At the end of 1912, Russia and the Mongols signed a treaty by which Russia acknowledged Mongol autonomy within the Republic of China; it also provided for Russian assistance in the training of a new Mongolian army and for Russian commercial privileges in Mongolia. Nevertheless, in the equivalent Mongolian version of the treaty, the terms designated independence were used. Both versions have the same value; so it was formally recognition of Mongolia as an independent state and its name Great Mongolian State. In 1913 Russia agreed to provide Mongolia with weapons and a loan of two million

While these efforts at obtaining international recognition continued, the Mongols and Russians were negotiating. At the end of 1912, Russia and the Mongols signed a treaty by which Russia acknowledged Mongol autonomy within the Republic of China; it also provided for Russian assistance in the training of a new Mongolian army and for Russian commercial privileges in Mongolia. Nevertheless, in the equivalent Mongolian version of the treaty, the terms designated independence were used. Both versions have the same value; so it was formally recognition of Mongolia as an independent state and its name Great Mongolian State. In 1913 Russia agreed to provide Mongolia with weapons and a loan of two million

A tripartite conference between the Russian Empire, Republic of China and the Bogd Khaan's government convened at

A tripartite conference between the Russian Empire, Republic of China and the Bogd Khaan's government convened at

In 1913, the Russian consulate in Urga began publishing a journal titled ''Shine tol (the New Mirror), the purpose of which was to project a positive image of Russia. Its editor, a Buryat-born scholar and statesman Ts. Zhamtsarano, turned it into a platform for advocating political and social change. Lamas were incensed over the first issue, which denied that the world was flat; another issue severely criticized the Mongolian nobility for its exploitation of ordinary people. Medical and veterinary services, part of Russian-sponsored reforms, met resistance from the lamas as this had been their prerogative. Mongols regarded as annoying the efforts of the Russians to oversee use of the second loan (the Russians believed the first had been profligately spent) and to reform the state budgetary system. The Russian diplomat Alexander Miller, appointed in 1913, proved to be a poor choice as he had little respect for most Mongolian officials, whom he regarded as incompetent in the extreme. The chief Russian military instructor successfully organized a Mongolian military brigade. Soldiers from this brigade manifested themselves later on in combat against Chinese troops.

The outbreak of the

In 1913, the Russian consulate in Urga began publishing a journal titled ''Shine tol (the New Mirror), the purpose of which was to project a positive image of Russia. Its editor, a Buryat-born scholar and statesman Ts. Zhamtsarano, turned it into a platform for advocating political and social change. Lamas were incensed over the first issue, which denied that the world was flat; another issue severely criticized the Mongolian nobility for its exploitation of ordinary people. Medical and veterinary services, part of Russian-sponsored reforms, met resistance from the lamas as this had been their prerogative. Mongols regarded as annoying the efforts of the Russians to oversee use of the second loan (the Russians believed the first had been profligately spent) and to reform the state budgetary system. The Russian diplomat Alexander Miller, appointed in 1913, proved to be a poor choice as he had little respect for most Mongolian officials, whom he regarded as incompetent in the extreme. The chief Russian military instructor successfully organized a Mongolian military brigade. Soldiers from this brigade manifested themselves later on in combat against Chinese troops.

The outbreak of the

In December 1915,

In December 1915,

Anti-Bolshevik forces in Asia were fragmented into a number of regiments. One was led by the Supreme Commander of the Baikal Cossacks, Grigory Semyonov, who had assembled a detachment of Buryats and Inner Mongolian nationalists for the creation of a pan-Mongolian state. Semyonov and his allies made several unsuccessful efforts to encourage the Bogd Khaan's government to join it. The Khalkha people regarded themselves as the natural leaders of all Mongols and feared being submerged into a new political system that likely would be led by Buryats, whom the Khalkhas deeply mistrusted. When inducements failed, Semyonov threatened to invade Mongolia to force compliance.

The Bogd Khaanate was in a difficult position. On the one hand, it lacked the strength to repel a pan-Mongolist attack; on the other, they were profoundly disquieted by the thought of more Chinese troops in Mongolia. The first detachment of Chinese troops arrived to Urga in July 1919. Prince N.A Kudashev, the old Imperial Russian ambassador to Beijing, indicated a violation of the Kyakhta Agreement by China.Kuzmin, S.L. 2011. The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, , p. 134 This step in conflict with the Kyakhta agreement was considered by the Chinese as the first step toward Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia. In any event, the threatened pan-Mongolian invasion never materialized because of dissension between the Buryats and Inner Mongolians, and Semyonov's dream of a pan-Mongolian state died.

Anti-Bolshevik forces in Asia were fragmented into a number of regiments. One was led by the Supreme Commander of the Baikal Cossacks, Grigory Semyonov, who had assembled a detachment of Buryats and Inner Mongolian nationalists for the creation of a pan-Mongolian state. Semyonov and his allies made several unsuccessful efforts to encourage the Bogd Khaan's government to join it. The Khalkha people regarded themselves as the natural leaders of all Mongols and feared being submerged into a new political system that likely would be led by Buryats, whom the Khalkhas deeply mistrusted. When inducements failed, Semyonov threatened to invade Mongolia to force compliance.

The Bogd Khaanate was in a difficult position. On the one hand, it lacked the strength to repel a pan-Mongolist attack; on the other, they were profoundly disquieted by the thought of more Chinese troops in Mongolia. The first detachment of Chinese troops arrived to Urga in July 1919. Prince N.A Kudashev, the old Imperial Russian ambassador to Beijing, indicated a violation of the Kyakhta Agreement by China.Kuzmin, S.L. 2011. The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, , p. 134 This step in conflict with the Kyakhta agreement was considered by the Chinese as the first step toward Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia. In any event, the threatened pan-Mongolian invasion never materialized because of dissension between the Buryats and Inner Mongolians, and Semyonov's dream of a pan-Mongolian state died.

A few months earlier the Chinese government had appointed as new Northwest Frontier Commissioner

A few months earlier the Chinese government had appointed as new Northwest Frontier Commissioner

The late Qing government had embarked on a grand plan, the "

The late Qing government had embarked on a grand plan, the "

The Bogd Khanate of Mongolia ( mn, , Богд хаант Монгол Улс; ) was the government of Outer Mongolia between 1911 and 1919 and again from 1921 to 1924. By the spring of 1911, some prominent Mongol nobles including Prince Tögs-Ochiryn Namnansüren persuaded the Jebstundamba Khutukhtu to convene a meeting of nobles and ecclesiastical officials to discuss independence from Qing China. On 30 November 1911 the Mongols established the Temporary Government of

At the time, the government was still composed of a feudal Khanate, which held its system in place largely with the power of agriculture, as most traditional pastoral societies of East Asia had been. The new Mongolian state was a fusion of very different elements: Western political institutions, Mongolian theocracy, and Qing imperial administrative and political traditions. 29 December was declared to be independence day and a national holiday. Urga (modern Ulan Bator), until then known to the Mongolians as the "Great Monastery" (''Ikh khüree''), was renamed "Capital Monastery" (''Niislel khüree'') to reflect its new role as the seat of government. A state name, "Great Mongolian State" (''Ikh Mongol uls''), and a state flag were adopted. A parliament (''ulsyn khura''l) was created, comprising upper and lower houses. A new Mongolian government was formed with five ministries: internal affairs, foreign affairs, finance, justice, and the army. Consequently, a national army was created.

The new state also reflected old ways; the Bogd Khaan adopted a reign title, "Elevated by the Many" (''Olnoo örgogdsön''), a style name used (it was believed) by the ancient kings of

At the time, the government was still composed of a feudal Khanate, which held its system in place largely with the power of agriculture, as most traditional pastoral societies of East Asia had been. The new Mongolian state was a fusion of very different elements: Western political institutions, Mongolian theocracy, and Qing imperial administrative and political traditions. 29 December was declared to be independence day and a national holiday. Urga (modern Ulan Bator), until then known to the Mongolians as the "Great Monastery" (''Ikh khüree''), was renamed "Capital Monastery" (''Niislel khüree'') to reflect its new role as the seat of government. A state name, "Great Mongolian State" (''Ikh Mongol uls''), and a state flag were adopted. A parliament (''ulsyn khura''l) was created, comprising upper and lower houses. A new Mongolian government was formed with five ministries: internal affairs, foreign affairs, finance, justice, and the army. Consequently, a national army was created.

The new state also reflected old ways; the Bogd Khaan adopted a reign title, "Elevated by the Many" (''Olnoo örgogdsön''), a style name used (it was believed) by the ancient kings of  The new state was theocratic, and its system suited Mongols, but it was not economically efficient as the leaders were inexperienced in such matters. The Qing dynasty had been careful to check the encroachment of religion into the secular arena; that restraint was now gone. State policy was directed by religious leaders, with relatively little participation by lay nobles. The parliament had only consultative powers; in any event, it did not meet until 1914. The Office of Religion and State, an extra-governmental body headed by a lama, played a role in directing political matters. The Ministry of Internal Affairs was vigilant in ensuring that senior ecclesiastics were treated with solemn deference by lay persons.

The head of the Bogd Khaan's Ecclesiastical Administration (''Shav' yamen'') endeavoured to transfer as many wealthy herdsmen as he could to the ecclesiastical estate (''Ikh shav), resulting in the population bearing an increasingly heavy tax burden. Ten-thousand Buddha statuettes were purchased in 1912 as propitiatory offerings to restore the Bogd Khaan's eyesight. A cast-iron statue of the Buddha, 84 feet tall, was brought from Dolonnor, and a temple was constructed to house the statue. ''D. Tsedev'', pp. 49–50. In 1914 the Ecclesiastical Administration ordered the government to defray the costs of a particular religious ceremony in the amount of 778,000 bricks of tea (the currency of the day), a gigantic sum.

The new state was theocratic, and its system suited Mongols, but it was not economically efficient as the leaders were inexperienced in such matters. The Qing dynasty had been careful to check the encroachment of religion into the secular arena; that restraint was now gone. State policy was directed by religious leaders, with relatively little participation by lay nobles. The parliament had only consultative powers; in any event, it did not meet until 1914. The Office of Religion and State, an extra-governmental body headed by a lama, played a role in directing political matters. The Ministry of Internal Affairs was vigilant in ensuring that senior ecclesiastics were treated with solemn deference by lay persons.

The head of the Bogd Khaan's Ecclesiastical Administration (''Shav' yamen'') endeavoured to transfer as many wealthy herdsmen as he could to the ecclesiastical estate (''Ikh shav), resulting in the population bearing an increasingly heavy tax burden. Ten-thousand Buddha statuettes were purchased in 1912 as propitiatory offerings to restore the Bogd Khaan's eyesight. A cast-iron statue of the Buddha, 84 feet tall, was brought from Dolonnor, and a temple was constructed to house the statue. ''D. Tsedev'', pp. 49–50. In 1914 the Ecclesiastical Administration ordered the government to defray the costs of a particular religious ceremony in the amount of 778,000 bricks of tea (the currency of the day), a gigantic sum.

Bogd Khan

Bogd Khan, , ; ( – 20 May 1924) was the khan of the Bogd Khaganate from 1911 to 1924, following the state's ''de facto'' independence from the Qing dynasty of China after the Xinhai Revolution. Born in Tibet, he was the third most importa ...

's Government">

File:Namnansuren2.jpg, Prime Minister Tögs-Ochiryn Namnansüren

File:Tserenchimed.jpg, Interior Minister Da Lam Tserenchimed

File:Ханддорж.jpg, Foreign Minister Mijiddorjiin Khanddorj

File:Г.Бадамдорж.jpg, Minister of Religion and State Gonchigjalzangiin Badamdorj

File:Манлайбаатар Дамдинсүрэн.jpg, Deputy Foreign Minister Manlaibaatar Damdinsüren

File:JalkhanzKhutagt2.jpg, Minister for the Pacification of the Western Border Areas Sodnomyn Damdinbazar

Khalkha

The Khalkha (Mongolian script, Mongolian: mn, Халх, Halh, , zh, 喀爾喀) have been the largest subgroup of Mongols, Mongol people in modern Mongolia since the 15th century. The Khalkha, together with Chahars, Ordos Mongols, Ordos and Tum ...

. On 29 December 1911 the Mongols declared their independence from the collapsing Qing dynasty following the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a ...

. They installed as theocratic sovereign the 8th Bogd Gegeen, highest authority of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

in Mongolia, who took the title ''Bogd Khan

Bogd Khan, , ; ( – 20 May 1924) was the khan of the Bogd Khaganate from 1911 to 1924, following the state's ''de facto'' independence from the Qing dynasty of China after the Xinhai Revolution. Born in Tibet, he was the third most importa ...

'' or "Holy Ruler". The Bogd Khaan was last khagan of the Mongols. This ushered in the period of "Theocratic Mongolia", and the realm of the Bogd Khan is usually known as the "Bogd Khanate".

Three historical currents were at work during this period. The first was the efforts of the Mongols to form an independent, theocratic state that included Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, Barga (also known as Hulunbuir), Upper Mongolia, Western Mongolia and Tannu Uriankhai (" pan-Mongolism"). The second was the Russian Empire's determination to achieve the twin goals of establishing its own preeminence in the country but at the same time ensuring Outer Mongolia's autonomy within the nascent Republic of China (ROC). The third was the ultimate success of the ROC in eliminating Outer Mongolian autonomy and establishing its full sovereignty over the region from 1919 to 1921.

Name

The Mongolian name used is generally "" (, State of Mongolia Elevated by the Many) or "Khaant uls" (, khagan country).Mongolian Revolution of 1911

On 2 February 1913 the Bogd Khanate sent Mongolian cavalry forces to liberateInner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

from China. The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

refused to sell weapons to the Bogd Khanate, and Russian Tsar Nicholas II spoke of "Mongolian imperialism". The only country to recognize Mongolia as a legitimate state was Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

, which also declared its independence from Qing China. Tibet and Mongolia later signed a friendship treaty and affirmed mutual recognition.

Government and society

At the time, the government was still composed of a feudal Khanate, which held its system in place largely with the power of agriculture, as most traditional pastoral societies of East Asia had been. The new Mongolian state was a fusion of very different elements: Western political institutions, Mongolian theocracy, and Qing imperial administrative and political traditions. 29 December was declared to be independence day and a national holiday. Urga (modern Ulan Bator), until then known to the Mongolians as the "Great Monastery" (''Ikh khüree''), was renamed "Capital Monastery" (''Niislel khüree'') to reflect its new role as the seat of government. A state name, "Great Mongolian State" (''Ikh Mongol uls''), and a state flag were adopted. A parliament (''ulsyn khura''l) was created, comprising upper and lower houses. A new Mongolian government was formed with five ministries: internal affairs, foreign affairs, finance, justice, and the army. Consequently, a national army was created.

The new state also reflected old ways; the Bogd Khaan adopted a reign title, "Elevated by the Many" (''Olnoo örgogdsön''), a style name used (it was believed) by the ancient kings of

At the time, the government was still composed of a feudal Khanate, which held its system in place largely with the power of agriculture, as most traditional pastoral societies of East Asia had been. The new Mongolian state was a fusion of very different elements: Western political institutions, Mongolian theocracy, and Qing imperial administrative and political traditions. 29 December was declared to be independence day and a national holiday. Urga (modern Ulan Bator), until then known to the Mongolians as the "Great Monastery" (''Ikh khüree''), was renamed "Capital Monastery" (''Niislel khüree'') to reflect its new role as the seat of government. A state name, "Great Mongolian State" (''Ikh Mongol uls''), and a state flag were adopted. A parliament (''ulsyn khura''l) was created, comprising upper and lower houses. A new Mongolian government was formed with five ministries: internal affairs, foreign affairs, finance, justice, and the army. Consequently, a national army was created.

The new state also reflected old ways; the Bogd Khaan adopted a reign title, "Elevated by the Many" (''Olnoo örgogdsön''), a style name used (it was believed) by the ancient kings of Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

. He promoted the ruling princes and lamas by one grade, an act traditionally performed by newly installed Chinese emperors. Lay and religious princes were instructed to render their annual tribute, the "nine whites". By tradition the "nine whites" were eight white horses and one white camel. On this occasion, the "nine whites" consisted of 3,500 horses and 200 camels sent to the Bogd Khaan instead of the Qing Emperor as in the past. Again, the Bogd Khaan appropriated to himself the right to confer ranks and seals of office upon the Mongolian nobility.

The Bogd Khaan himself was the inevitable choice as leader of the state in view of his stature as the revered symbol of Buddhism in Mongolia

Buddhism is the largest and official religion of Mongolia practiced by 53% of Mongolia's population, according to the 2010 Mongolia census. Buddhism in Mongolia derives much of its recent characteristics from Tibetan Buddhism of the Gelug a ...

. He was famed throughout the country for his special oracular and supernatural powers and as the Great Khan of Mongols. He established contacts with foreign powers, tried to assist development of economy (mainly agriculture and military issues), but his main goal was development of Buddhism in Mongolia.

The new state was theocratic, and its system suited Mongols, but it was not economically efficient as the leaders were inexperienced in such matters. The Qing dynasty had been careful to check the encroachment of religion into the secular arena; that restraint was now gone. State policy was directed by religious leaders, with relatively little participation by lay nobles. The parliament had only consultative powers; in any event, it did not meet until 1914. The Office of Religion and State, an extra-governmental body headed by a lama, played a role in directing political matters. The Ministry of Internal Affairs was vigilant in ensuring that senior ecclesiastics were treated with solemn deference by lay persons.

The head of the Bogd Khaan's Ecclesiastical Administration (''Shav' yamen'') endeavoured to transfer as many wealthy herdsmen as he could to the ecclesiastical estate (''Ikh shav), resulting in the population bearing an increasingly heavy tax burden. Ten-thousand Buddha statuettes were purchased in 1912 as propitiatory offerings to restore the Bogd Khaan's eyesight. A cast-iron statue of the Buddha, 84 feet tall, was brought from Dolonnor, and a temple was constructed to house the statue. ''D. Tsedev'', pp. 49–50. In 1914 the Ecclesiastical Administration ordered the government to defray the costs of a particular religious ceremony in the amount of 778,000 bricks of tea (the currency of the day), a gigantic sum.

The new state was theocratic, and its system suited Mongols, but it was not economically efficient as the leaders were inexperienced in such matters. The Qing dynasty had been careful to check the encroachment of religion into the secular arena; that restraint was now gone. State policy was directed by religious leaders, with relatively little participation by lay nobles. The parliament had only consultative powers; in any event, it did not meet until 1914. The Office of Religion and State, an extra-governmental body headed by a lama, played a role in directing political matters. The Ministry of Internal Affairs was vigilant in ensuring that senior ecclesiastics were treated with solemn deference by lay persons.

The head of the Bogd Khaan's Ecclesiastical Administration (''Shav' yamen'') endeavoured to transfer as many wealthy herdsmen as he could to the ecclesiastical estate (''Ikh shav), resulting in the population bearing an increasingly heavy tax burden. Ten-thousand Buddha statuettes were purchased in 1912 as propitiatory offerings to restore the Bogd Khaan's eyesight. A cast-iron statue of the Buddha, 84 feet tall, was brought from Dolonnor, and a temple was constructed to house the statue. ''D. Tsedev'', pp. 49–50. In 1914 the Ecclesiastical Administration ordered the government to defray the costs of a particular religious ceremony in the amount of 778,000 bricks of tea (the currency of the day), a gigantic sum.

Diplomatic maneuvering over Mongolia

The new government under Bogd Khan tried to seek international recognition, particularly from the Russian government. The

The new government under Bogd Khan tried to seek international recognition, particularly from the Russian government. The Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

however, rejected the Mongolian plea for recognition, due to a common Russian Imperial ambition at the time to take over the central Asian states, and Mongolia was planned for further expansion. Throughout the Bogd Khaan era, the positions of the governments of China and Russia were clear and consistent. China was adamant that Mongolia was, and must remain, an integral part of China. The (provisional) constitution of the new Chinese republic contained an uncompromising statement to this effect. A law dealing with the election of the Chinese National Assembly provided for delegates from Outer Mongolia. For their part, the Russian Imperial government accepted the principle that Mongolia must remain formally part of China; however, Russia was equally determined that Mongolia possess autonomous powers so substantial as to make it quasi-independent, so they recognised the autonomy of the region. Russian Empire could not act on the ambition due to internal struggles, which allowed Russia to claim that Mongolia was under her protection. Thus, in 1912 Russia concluded a secret convention with the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

delineating their respective spheres of influence: South Manchuria and Inner Mongolia fell to the Japanese, North Manchuria and Outer Mongolia to the Russians. Bogd Khaan said to Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

, the President of the Republic of China "I established our own state before you, Mongols and Chinese have different origins, our languages and scripts are different. You're not the Manchu's descendants, so how can you think China is the Manchu's successor

Successor may refer to:

* An entity that comes after another (see Succession (disambiguation))

Film and TV

* ''The Successor'' (film), a 1996 film including Laura Girling

* ''The Successor'' (TV program), a 2007 Israeli television program Musi ...

?".

In spite of Chinese and Russian opposition, the Mongols were tireless in their efforts to attract international recognition of their independence. Diplomatic notes were sent to foreign consulates in Hailar; none responded. A delegation went to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

the purpose of which, among other things, was to contact European ambassadors expressing the desire for diplomatic relations. The Russians did not permit these contacts. A later delegation to Saint Petersburg sent notes to Western ambassadors announcing Mongolia's independence and formation of a pan-Mongolian state; again none responded. The Mongols attempted to send a delegation to Japan but the Japanese consul at Harbin prevented it from proceeding further.

While these efforts at obtaining international recognition continued, the Mongols and Russians were negotiating. At the end of 1912, Russia and the Mongols signed a treaty by which Russia acknowledged Mongol autonomy within the Republic of China; it also provided for Russian assistance in the training of a new Mongolian army and for Russian commercial privileges in Mongolia. Nevertheless, in the equivalent Mongolian version of the treaty, the terms designated independence were used. Both versions have the same value; so it was formally recognition of Mongolia as an independent state and its name Great Mongolian State. In 1913 Russia agreed to provide Mongolia with weapons and a loan of two million

While these efforts at obtaining international recognition continued, the Mongols and Russians were negotiating. At the end of 1912, Russia and the Mongols signed a treaty by which Russia acknowledged Mongol autonomy within the Republic of China; it also provided for Russian assistance in the training of a new Mongolian army and for Russian commercial privileges in Mongolia. Nevertheless, in the equivalent Mongolian version of the treaty, the terms designated independence were used. Both versions have the same value; so it was formally recognition of Mongolia as an independent state and its name Great Mongolian State. In 1913 Russia agreed to provide Mongolia with weapons and a loan of two million ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

s. In 1913, Mongolia and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

signed a bilateral treaty A bilateral treaty (also called a bipartite treaty) is a treaty strictly between two state entities. It is an agreement made by negotiations between two parties, established in writing and signed by representatives of the parties. Treaties can span ...

, recognizing each other as independent states.

In November 1913, there was a Sino-Russian Declaration which recognised Mongolia as part of China but with internal autonomy; further, China agreed not to send troops or officials to Mongolia, or to permit colonization of the country; it was also to accept the "good offices" of Russia in Chinese-Mongolian affairs. There was to be a tripartite conference, in which Russia, China, and the "authorities" of Mongolia would participate. This declaration was not considered by Mongolia to be legitimate as the Mongolian government had not participated in the decision.

To reduce tensions, the Russians agreed to provide Mongolia with more weapons and a second loan, this time three million rubles. There were other agreements between Russia and Mongolia in these early years concerning weapons, military instructors, telegraph, and railroad that were either concluded or nearly so by the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914.

In April 1914, the northern region of Tannu Uriankhai was formally accepted as a Russian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

.

Kyakhta Agreement of 1915

A tripartite conference between the Russian Empire, Republic of China and the Bogd Khaan's government convened at

A tripartite conference between the Russian Empire, Republic of China and the Bogd Khaan's government convened at Kyakhta

Kyakhta (russian: Кя́хта, ; bua, Хяагта, Khiaagta, ; mn, Хиагт, Hiagt, ) is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located on the Kyakhta River near the Mongolia–Rus ...

in the autumn of 1914. The Mongolian representative, Prime Minister Tögs-Ochiryn Namnansüren, were determined to stretch autonomy into de facto independence, and to deny the Chinese anything more than vague, ineffectual suzerain powers. The Chinese sought to minimize, if not to end, Mongolian autonomy. The Russian position was somewhere in between. The result was the Kyakhta Treaty of June 1915, which recognised Mongolia's autonomy within the Chinese state. Nevertheless, Outer Mongolia remained effectively outside Chinese control and retained main features of the state according to international law of that time.

The Mongolians viewed the treaty as a disaster because it denied the recognition of a truly independent, all-Mongolian state. China regarded the treaty in a similar fashion, consenting only because it was preoccupied with other international problems, especially Japan. The treaty did contain one significant feature which the Chinese were later to turn to their advantage; the right to appoint a high commissioner to Urga and deputy high commissioners to Uliastai, Khovd, and Kyakhta

Kyakhta (russian: Кя́хта, ; bua, Хяагта, Khiaagta, ; mn, Хиагт, Hiagt, ) is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located on the Kyakhta River near the Mongolia–Rus ...

. This provided a senior political presence in Mongolia, which had been lacking.

Decline of Russian influence

In 1913, the Russian consulate in Urga began publishing a journal titled ''Shine tol (the New Mirror), the purpose of which was to project a positive image of Russia. Its editor, a Buryat-born scholar and statesman Ts. Zhamtsarano, turned it into a platform for advocating political and social change. Lamas were incensed over the first issue, which denied that the world was flat; another issue severely criticized the Mongolian nobility for its exploitation of ordinary people. Medical and veterinary services, part of Russian-sponsored reforms, met resistance from the lamas as this had been their prerogative. Mongols regarded as annoying the efforts of the Russians to oversee use of the second loan (the Russians believed the first had been profligately spent) and to reform the state budgetary system. The Russian diplomat Alexander Miller, appointed in 1913, proved to be a poor choice as he had little respect for most Mongolian officials, whom he regarded as incompetent in the extreme. The chief Russian military instructor successfully organized a Mongolian military brigade. Soldiers from this brigade manifested themselves later on in combat against Chinese troops.

The outbreak of the

In 1913, the Russian consulate in Urga began publishing a journal titled ''Shine tol (the New Mirror), the purpose of which was to project a positive image of Russia. Its editor, a Buryat-born scholar and statesman Ts. Zhamtsarano, turned it into a platform for advocating political and social change. Lamas were incensed over the first issue, which denied that the world was flat; another issue severely criticized the Mongolian nobility for its exploitation of ordinary people. Medical and veterinary services, part of Russian-sponsored reforms, met resistance from the lamas as this had been their prerogative. Mongols regarded as annoying the efforts of the Russians to oversee use of the second loan (the Russians believed the first had been profligately spent) and to reform the state budgetary system. The Russian diplomat Alexander Miller, appointed in 1913, proved to be a poor choice as he had little respect for most Mongolian officials, whom he regarded as incompetent in the extreme. The chief Russian military instructor successfully organized a Mongolian military brigade. Soldiers from this brigade manifested themselves later on in combat against Chinese troops.

The outbreak of the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914 required Russia to redirect its energies to Europe. By the middle of 1915, the Russian military position had deteriorated so badly that the Russian government had no choice but to neglect its Asian interests. China soon took advantage of the Russian distractions which increased dramatically following the Bolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in 1917.

Chinese attempts to "reintegrate" Mongolia

In December 1915,

In December 1915, Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

, the President of the Republic of China, sent gifts to the Bogd Khaan and his wife. In return, the Bogd Khaan dispatched a delegation of 30 persons to Beijing with gifts for Yuan: four white horses and two camels (his wife Ekh Dagina sent four black horses and two camels). The delegation was received by Yuan Shikai himself, now proclaimed ruler of a restored Empire of China. The delegation met Yuan Shikai on 10 February 1916. In China this was interpreted in the context of the traditional tributary system, when all missions with gifts to Chinese rulers were considered as signs of submission. In this regard, Chinese sources stated that a year later, the Bogd Khaan agreed to participate in an investiture ceremony – a formal Qing ritual by which frontier nobles received the patent and seal of imperial appointment to office; Yuan awarded him China's highest decoration of merit; lesser but significant decorations were awarded to other senior Mongolian princes. Actually, after the conclusion of the Kyakhta agreement in 1914, Yuan Shikai sent a telegram to the Bogd Khaan informing him that he was bestowed a title of "Bogd Jevzundamba Khutuktu Khaan of Outer Mongolia" and would be provided with a golden seal and a golden diploma. The Bogd Khaan responded: "''Since the title of Bogd Jevzundamba Khutuktu Khaan of Outer Mongolia was already bestowed by the Ikh Juntan, there was no need to bestow it again and that since there was no provision on the golden seal and golden diploma in the tripartite agreement, his government was not in a position to receive them''". The Bogd Khaan had already been granted said golden seal, title and diploma by the Qing dynasty.

Revolution and civil war in Russia

TheBolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in 1917 and the resultant outbreak of civil war in Russia provided new opportunities for China to move into Mongolia. The Bolsheviks established workers' councils

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, a process essentially completed by the summer of 1918. The presence of the Bolsheviks so close to the Mongolian border unsettled both the Mongolians and the Chinese High Commissioner, Chen Yi. Rumours were rife of Bolshevik troops preparing to invade Mongolia. The Cossack consular guards at Urga, Uliastai, and Khovd, traditionally loyal to the Imperial House of Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastacia of Russia, Anastasi ...

, had mutinied and left. The Russian communities in Mongolia were themselves becoming fractious, some openly supporting the new Bolshevik regime. The pretext was the penetration of the White Russian troops from Siberia. Chen Yi sent telegrams to Beijing requesting troops and, after several efforts, was able to persuade the Bogd Khaan's government to agree to the introduction of one battalion. By July 1918, the Soviet threat from Siberia had faded and the Mongolian foreign minister told Chen Yi that troops were no longer needed. Nevertheless, the Chinese battalion continued to move and in August arrived to Urga.

Anti-Bolshevik forces in Asia were fragmented into a number of regiments. One was led by the Supreme Commander of the Baikal Cossacks, Grigory Semyonov, who had assembled a detachment of Buryats and Inner Mongolian nationalists for the creation of a pan-Mongolian state. Semyonov and his allies made several unsuccessful efforts to encourage the Bogd Khaan's government to join it. The Khalkha people regarded themselves as the natural leaders of all Mongols and feared being submerged into a new political system that likely would be led by Buryats, whom the Khalkhas deeply mistrusted. When inducements failed, Semyonov threatened to invade Mongolia to force compliance.

The Bogd Khaanate was in a difficult position. On the one hand, it lacked the strength to repel a pan-Mongolist attack; on the other, they were profoundly disquieted by the thought of more Chinese troops in Mongolia. The first detachment of Chinese troops arrived to Urga in July 1919. Prince N.A Kudashev, the old Imperial Russian ambassador to Beijing, indicated a violation of the Kyakhta Agreement by China.Kuzmin, S.L. 2011. The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, , p. 134 This step in conflict with the Kyakhta agreement was considered by the Chinese as the first step toward Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia. In any event, the threatened pan-Mongolian invasion never materialized because of dissension between the Buryats and Inner Mongolians, and Semyonov's dream of a pan-Mongolian state died.

Anti-Bolshevik forces in Asia were fragmented into a number of regiments. One was led by the Supreme Commander of the Baikal Cossacks, Grigory Semyonov, who had assembled a detachment of Buryats and Inner Mongolian nationalists for the creation of a pan-Mongolian state. Semyonov and his allies made several unsuccessful efforts to encourage the Bogd Khaan's government to join it. The Khalkha people regarded themselves as the natural leaders of all Mongols and feared being submerged into a new political system that likely would be led by Buryats, whom the Khalkhas deeply mistrusted. When inducements failed, Semyonov threatened to invade Mongolia to force compliance.

The Bogd Khaanate was in a difficult position. On the one hand, it lacked the strength to repel a pan-Mongolist attack; on the other, they were profoundly disquieted by the thought of more Chinese troops in Mongolia. The first detachment of Chinese troops arrived to Urga in July 1919. Prince N.A Kudashev, the old Imperial Russian ambassador to Beijing, indicated a violation of the Kyakhta Agreement by China.Kuzmin, S.L. 2011. The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, , p. 134 This step in conflict with the Kyakhta agreement was considered by the Chinese as the first step toward Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia. In any event, the threatened pan-Mongolian invasion never materialized because of dissension between the Buryats and Inner Mongolians, and Semyonov's dream of a pan-Mongolian state died.

Abolition of Mongolian autonomy

On 4 August 1919, an assembly of princes took place in Urga to discuss Semyonov's invitation to join the pan-Mongolian movement; this was because Khalkhas were threatened by a pan-Mongolist group of one Mongolian and two Buryat regiments advancing from Dauria. While that military campaign failed, China continued to increase troop numbers in Mongolia. On 13 August 1919 Commissioner Chen Yi received a message from "representatives of the four aimags", requesting that China come to Mongolia's aid against Semyonov; it also expressed the desire of the Khalkha nobility to restore the previous Qing system. Among other things, they proposed that the five ministries of the Mongolian government be placed under the direct supervision of the Chinese high commission rather than the Bogd Khaan. According to an Associated Press dispatch, some Mongol chieftains signed a petition asking China to retake administration of Mongolia and end Outer Mongolia's autonomy. Pressure from Chen Yi on Mongolian princes followed; representatives of the Bogd Khaan also participated in negotiations. Eventually, the princes agreed on a long list of principles, sixty-four points "''On respecting of Outer Mongolia by the government of China and improvement of her position in future after self-abolishing of authonomy''". This document offered the replacement of the Mongolian government with Chinese officials, the introduction of Chinese garrisons and keeping of feudal titles. According to ambassador Kudashev, the majority of princes supported the abolition of autonomy. The Bogd Khaan sent a delegation to the President of China with a letter complaining that the plan to abolish autonomy was a contrivance of the High Commissioner alone and not the wish of the people of Mongolia. On 28 October 1919, the Chinese National Assembly approved the articles. PresidentXu Shichang

Xu Shichang (Hsu Shih-chang; ; courtesy name: Juren (Chu-jen; 菊人); October 20, 1855 – June 5, 1939) was the President of the Republic of China, in Beijing, from 10 October 1918 to 2 June 1922. The only permanent president of the Beiyang ...

sent a conciliatory letter to the Bogd Khaan, pledging respect for Mongolian feelings and reverence for the Jebtsundamba Khututktu and the Buddhist faith.

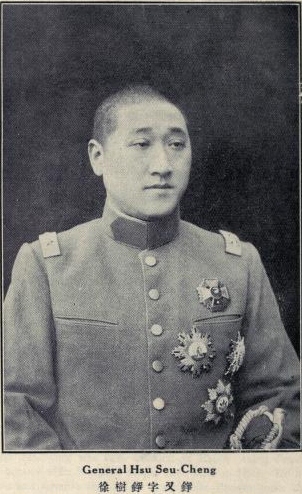

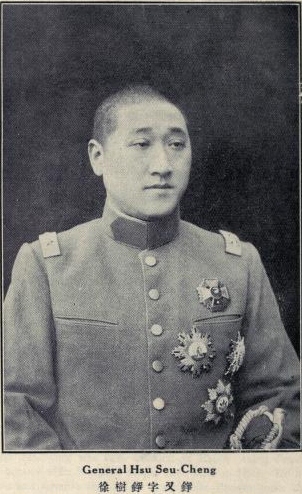

A few months earlier the Chinese government had appointed as new Northwest Frontier Commissioner

A few months earlier the Chinese government had appointed as new Northwest Frontier Commissioner Xu Shuzheng

Hsu Seu-Cheng or Xu Shuzheng (; ) (11 November 1880 – 29 December 1925) was a Chinese warlord in Republican China. A subordinate and right-hand man of Duan Qirui, he was a prominent member of the Anhui clique.

Early life

Xu was born in ...

, an influential warlord and prominent member of the pro-Japanese Anhui clique in the Chinese National Assembly. Xu had a vision for Mongolia very different from that reflected in the Sixty-four points. It presented a vast plan for reconstruction. Arriving with a military escort in Urga on 29 October, he informed the Mongolians that the Sixty-four points would need to be renegotiated. He submitted a much tougher set of conditions, the "Eight Articles," calling for the express declaration of Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia, an increase in Mongolia's population (presumably through Chinese colonization), and the promotion of commerce, industry, and agriculture. The Mongols resisted, prompting Xu to threaten to deport the Bogd Khaan to China if he did not immediately agree to the conditions. To emphasize the point, Xu placed troops in front of the Bogd Khaan's palace. The Japanese were the ones who ordered these pro-Japanese Chinese warlords to occupy Mongolia to halt a possibly revolutionary spillover from the Russian revolutionaries into Mongolia and Northern China. After the Chinese completed the occupation, the Japanese then abandoned them and left them on their own.

The Eight Articles were placed before the Mongolian Parliament on 15 November. The upper house accepted the Articles; the lower house did not, with some members calling for armed resistance, if necessary. The Buddhist monks resisted most of all, but the nobles of the upper house prevailed. A petition to end autonomy, signed by the ministers and deputy ministers of the Bogd Khaan's government, was presented to Xu. The Bogd Khaan refused to affix his seal until compelled by the fact that new Prime Minister Gonchigjalzangiin Badamdorj, installed by order of Xu Shuzheng, and conservative forces were accepting the Chinese demands. The office of the high commission was abolished, and Chen Yi was recalled. Xu's success was broadly celebrated in China. 1 January and the following days were declared holidays and all governmental institutions in Beijing and in the provinces were closed.

Xu Shuzheng returned to Mongolia in December for the Bogd Khaan's "investiture", which took place on 1 January 1920. It was an elaborate ceremony: Chinese soldiers lined both sides of the road to the palace; the portrait of the President of China was borne on a palanquin, followed by the national flag of China and a marching band of cymbals and drums. Mongols were obliged to prostrate themselves before these emblems of Chinese sovereignty. That night herdsmen and lamas gathered outside the palace and angrily tore down the flags of the Chinese Republic hanging from the gate.

Xu moved immediately to implement the Eight Articles. The doors of the former Mongolian ministries were locked, and Chinese sentries posted in front. A new government of eight departments was formed. The Mongolian army was demobilized, its arsenal seized, and both lay and religious officials banned from using the words "Mongolian state" (Mongol uls) in their official correspondence.

The Tusiyetu Khan Aimak's Prince Darchin Ch'in Wang was a supporter of Chinese rule while his younger brother Tsewang was a supporter of Ungern-Sternberg.

Conclusion

The late Qing government had embarked on a grand plan, the "

The late Qing government had embarked on a grand plan, the "New Policies

Late Qing reforms (), commonly known as New Policies of the late Qing dynasty (), or New Deal of the late Qing dynasty, simply referred to as New Policies, were a series of cultural, economic, educational, military, and political reforms implemen ...

", aimed at greater integration of Mongolia with the rest of China and opened Han colonization and agricultural settlement. Many Mongols considered this act as a violation of the old agreements when they recognized authority of the Manchu dynasty, particularly the preservation of traditional social order on Mongol lands, and thus began to seek independence. The collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, conducted under the nationalistic catchwords of the Han Chinese, led to the formation of the Republic of China; later the initial concept was called " Five Races Under One Union". The newly founded Chinese state laid claim to all imperial territory, including Mongolia. Mongolian officials were clear that their subordination was to the Qing monarch and thus owed no allegiance to the new Chinese republic. While some Inner Mongols showed willingness to join the Republic of China, Outer Mongols, together with part of Inner Mongolia, declared independence from China. The Outer Mongols were helped by the White Russian troops of Baron R.F. von Ungern-Sternberg incursions following the Russian Revolution of 1917.Kuzmin, S.L. 2011. The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK Sci. Press, , pp. 120–199. The abolition of Mongolian autonomy by Xu Shuzheng in 1919 reawakened the Mongolian national independence movement. Two small resistance groups formed, later to become the Mongolian People's Party (renamed the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party), which sought independence and Soviet cooperation.

It was proposed that Zhang Zuolin

Zhang Zuolin (; March 19, 1875 June 4, 1928), courtesy name Yuting (雨亭), nicknamed Zhang Laogang (張老疙瘩), was an influential Chinese bandit, soldier, and warlord during the Warlord Era in China. The warlord of Manchuria from 1916 to ...

's domain (the Chinese " Three Eastern Provinces") take Outer Mongolia under its administration by the Bogda Khan and Bodo in 1922 after pro-Soviet Mongolian Communists seized control of Outer Mongolia.

See also

* Mongolia under Qing rule * Occupation of Mongolia *Mongolian Revolution of 1921

The Mongolian Revolution of 1921 ( Outer Mongolian Revolution of 1921, or People's Revolution of 1921) was a military and political event by which Mongolian revolutionaries, with the assistance of the Soviet Red Army, expelled Russian White Gua ...

*Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

Notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mongolia (1911-24 Mongol states 1910s in Mongolia 1920s in Mongolia Former countries in Central Asia Former theocracies Former monarchies Former monarchies of Asia Former unrecognized countries Former countries in Chinese history History of Mongolia 1910s establishments in Mongolia 20th-century disestablishments in Mongolia 1911 establishments in Asia 1924 disestablishments in Asia 20th century in Mongolia Former countries of the interwar period States and territories disestablished in 1924 States and territories established in 1911