Molly Maguires on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Molly Maguires were an

politics.ie; accessed 8 September 2015.

/ref> noted: After six months, the strike was defeated and the miners returned to work, accepting the 20 percent cut in pay. But miners belonging to the Ancient Order of Hibernians continued the fight. McParland acknowledged increasing support for the Mollies in his reports: Men, who last winter would not notice a Molly Maguire, are now glad to take them by the hand and make much of them. If the bosses exercise tyranny over the men they appear to look to the association for help. Lukas observes that the defeat was humiliating, and traces the roots of violence by the Mollies in the aftermath of the failed strike: Judges, lawyers, and policemen were overwhelmingly Welsh, German, or English ... When the coalfield Irish sought to remedy their grievances through the courts, they often met delays, obfuscation, or doors slammed in their faces. No longer looking to these institutions for justice, they turned instead to the Mollies.... Before the summer was over, six men—all Welsh or German—paid with their lives. Authors Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais argue that the killings were not one-sided:

However, Kerrigan's wife testified in the courtroom that her husband had committed the murder. She testified that she refused to provide her husband with clothing while he was in prison, because he had "picked innocent men to suffer for his crime". She stated that she was speaking out voluntarily, and was only interested in telling the truth about the murder. Gowen cross-examined her, but could not shake her testimony. Others supported her testimony amid speculation that Kerrigan was receiving special treatment due to the fact that McParland was engaged to his sister-in-law, Mary Ann Higgins. This trial was declared a mistrial due to the death of one of the jurors. A new trial was granted two months later. During that trial Fanny Kerrigan did not testify. The five defendants were sentenced to death. Kerrigan was allowed to go free.

The trial of Tom Munley for the murders of Thomas Sanger, a mine foreman, and William Uren, relied entirely on the testimony of McParland, and the eyewitness account of a witness. The witness stated under oath that he had seen the murderer clearly, and that Munley was not the murderer. Yet the jury accepted McParland's testimony that Munley had privately confessed to the murder. Munley was sentenced to death. Another four miners were put on trial and were found guilty on a charge of murder. McParland had no direct evidence, but had recorded that the four admitted their guilt to him. Kelly was being held in a cell for murder, and he was reputedly quoted as saying: "I would squeal on Jesus Christ to get out of here." In return for his testimony, the murder charge against him was dismissed.

In November, McAllister was convicted. McParland's testimony in the Molly Maguires trials helped send ten men to the gallows. The defense attorneys repeatedly sought to portray McParland as an

However, Kerrigan's wife testified in the courtroom that her husband had committed the murder. She testified that she refused to provide her husband with clothing while he was in prison, because he had "picked innocent men to suffer for his crime". She stated that she was speaking out voluntarily, and was only interested in telling the truth about the murder. Gowen cross-examined her, but could not shake her testimony. Others supported her testimony amid speculation that Kerrigan was receiving special treatment due to the fact that McParland was engaged to his sister-in-law, Mary Ann Higgins. This trial was declared a mistrial due to the death of one of the jurors. A new trial was granted two months later. During that trial Fanny Kerrigan did not testify. The five defendants were sentenced to death. Kerrigan was allowed to go free.

The trial of Tom Munley for the murders of Thomas Sanger, a mine foreman, and William Uren, relied entirely on the testimony of McParland, and the eyewitness account of a witness. The witness stated under oath that he had seen the murderer clearly, and that Munley was not the murderer. Yet the jury accepted McParland's testimony that Munley had privately confessed to the murder. Munley was sentenced to death. Another four miners were put on trial and were found guilty on a charge of murder. McParland had no direct evidence, but had recorded that the four admitted their guilt to him. Kelly was being held in a cell for murder, and he was reputedly quoted as saying: "I would squeal on Jesus Christ to get out of here." In return for his testimony, the murder charge against him was dismissed.

In November, McAllister was convicted. McParland's testimony in the Molly Maguires trials helped send ten men to the gallows. The defense attorneys repeatedly sought to portray McParland as an

On 21 June 1877, six men were hanged in the prison at Pottsville, and four at Mauch Chunk, Carbon County. A scaffold had been erected in the Carbon County Jail. State militia with fixed bayonets surrounded the prisons and the scaffolds. Miners arrived with their wives and children from the surrounding areas, walking through the night to honor the accused, and by nine o'clock "the crowd in Pottsville stretched as far as one could see." The families were silent, which was "the people's way of paying tribute" to those about to die. Thomas Munley's aged father had walked more than from Gilberton to assure his son that he believed in his innocence. Munley's wife arrived a few minutes after they closed the gate, and they refused to open it even for close relatives to say their final good-byes. She screamed at the gate with grief, throwing herself against it until she collapsed, but she was not allowed to pass. Four ( Alexander Campbell, John "Yellow Jack" Donahue, Michael J. Doyle and Edward J. Kelly) were hanged on 21 June 1877, at a Carbon County prison in Mauch Chunk (renamed Jim Thorpe in 1953), for the murders of John P. Jones and Morgan Powell, both mine bosses, following a trial later described by a Carbon County judge, John P. Lavelle, as follows:

Campbell, just before his execution, allegedly slapped a muddy handprint on his cell wall stating "There is proof of my words. That mark of mine will never be wiped out. It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man." Doyle and Hugh McGeehan were led to the scaffold. They were followed by Thomas Munley, James Carroll, James Roarity, James Boyle, Thomas Duffy, Kelly, Campbell, and "Yellow Jack" Donahue. Judge Dreher presided over the trials. Ten more condemned, Thomas Fisher, John "Black Jack" Kehoe, Patrick Hester, Peter McHugh, Patrick Tully, Peter McManus, Dennis Donnelly, Martin Bergan, James McDonnell and Charles Sharpe, were hanged at Mauch Chunk, Pottsville, Bloomsburg and Sunbury over the next two years. Peter McManus was the last Molly Maguire to be tried and convicted for murder at the Northumberland County Courthouse in 1878. ''Note:'' This includes

On 21 June 1877, six men were hanged in the prison at Pottsville, and four at Mauch Chunk, Carbon County. A scaffold had been erected in the Carbon County Jail. State militia with fixed bayonets surrounded the prisons and the scaffolds. Miners arrived with their wives and children from the surrounding areas, walking through the night to honor the accused, and by nine o'clock "the crowd in Pottsville stretched as far as one could see." The families were silent, which was "the people's way of paying tribute" to those about to die. Thomas Munley's aged father had walked more than from Gilberton to assure his son that he believed in his innocence. Munley's wife arrived a few minutes after they closed the gate, and they refused to open it even for close relatives to say their final good-byes. She screamed at the gate with grief, throwing herself against it until she collapsed, but she was not allowed to pass. Four ( Alexander Campbell, John "Yellow Jack" Donahue, Michael J. Doyle and Edward J. Kelly) were hanged on 21 June 1877, at a Carbon County prison in Mauch Chunk (renamed Jim Thorpe in 1953), for the murders of John P. Jones and Morgan Powell, both mine bosses, following a trial later described by a Carbon County judge, John P. Lavelle, as follows:

Campbell, just before his execution, allegedly slapped a muddy handprint on his cell wall stating "There is proof of my words. That mark of mine will never be wiped out. It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man." Doyle and Hugh McGeehan were led to the scaffold. They were followed by Thomas Munley, James Carroll, James Roarity, James Boyle, Thomas Duffy, Kelly, Campbell, and "Yellow Jack" Donahue. Judge Dreher presided over the trials. Ten more condemned, Thomas Fisher, John "Black Jack" Kehoe, Patrick Hester, Peter McHugh, Patrick Tully, Peter McManus, Dennis Donnelly, Martin Bergan, James McDonnell and Charles Sharpe, were hanged at Mauch Chunk, Pottsville, Bloomsburg and Sunbury over the next two years. Peter McManus was the last Molly Maguire to be tried and convicted for murder at the Northumberland County Courthouse in 1878. ''Note:'' This includes

''The Molly Maguires: The Origin, Growth, and Character of the Organization.''

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1877. * Pinkerton, Allan; ''The Mollie Maguires and the Detectives''; New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Publishers, 1877.

''Making Sense of the Molly Maguires''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. * Kenny, Kevin. "The Molly Maguires in Popular Culture", ''Journal of American Ethnic History,'' vol. 14, no. 4 (1995), pp. 27–46. * Kenny, Kevin. "The Molly Maguires and the Catholic Church", ''Labor History,'' vol. 36, no. 3 (1995), pp. 345–376. * Lens, Sidney. ''The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sitdowns.'' New York: Doubleday, 1973. * Morn, Frank. ''The Eye that Never Sleeps: A History of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.'' Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982. * Rayback, Joseph G. ''A History of American Labor.'' Rev. and exp. ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1974. {{ISBN, 1-299-50529-5

Audio interview with Irish-American historian and author John Kearns about the Molly Maguires

A Selection of Links for Coal Mining, Mine Fires, & The Molly Maguires

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050208025352/http://www.pacoalhistory.com/history/mollies.html Mollies and Black Diamonds

''The Molly Maguires and the Detectives'' (1877)

Documents in the Hagley Library Digital Archives

Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania 19th century in Pennsylvania Mining in Pennsylvania History of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania Irish secret societies Irish-American culture in Pennsylvania Irish-American history Labor disputes in the United States Miners' labor disputes in the United States Mining in the United States

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

19th-century secret society active in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

and parts of the Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

, best known for their activism among Irish-American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

and Irish immigrant coal miner

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

s in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. After a series of often violent conflicts, twenty suspected members of the Molly Maguires were convicted of murder and other crimes and were executed by hanging in 1877 and 1878. This history remains part of local Pennsylvania lore and the actual facts much debated among historians.

In Ireland

The Molly Maguires originated inIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, where secret societies with names such as Whiteboys

The Whiteboys ( ga, na Buachaillí Bána) were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in the ...

and Peep o' Day Boys were common beginning in the 18th century and through most of the 19th century. In some areas the terms ''Ribbonmen'' and ''Molly Maguires'' were both used for similar activism but at different times. The main distinction between the two appears to be that the Ribbonmen were regarded as "secular, cosmopolitan, and protonationalist", with the Molly Maguires considered "rural, local, and Gaelic".

Agrarian rebellion in Ireland can be traced to local concerns and grievances relating to land usage, particularly as traditional socioeconomic practices such as small-scale potato cultivation were supplanted by the fencing and pasturing of land (known as enclosure

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or " common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

). Agrarian resistance often took the form of fence destruction, night-time plowing of croplands that had been converted to pasture, and killing, mutilating, or driving off livestock. In areas where the land had long been dedicated to small-scale, growing-season leases of farmland, called conacre

Conacre (a corruption of ''corn-acre''), in Ireland, is a system of letting land, formerly in small patches or strips, and usually for tillage (growth of corn or potatoes).

Concept

Most common in Munster and Connacht for a variety of crops, in L ...

, opposition was conceived as "retributive justice" that was intended "to correct transgressions against traditional moral and social codes".Kenny, pp. 18-21.

The victims of agrarian violence were frequently Irish land agents, middlemen, and tenants. Merchants and millers were often threatened or attacked if their prices were high. Landlords' agents were threatened, beaten, and assassinated. New tenants on lands secured by evictions also became targets. Local leaders were reported to have sometimes dressed as women, i.e., as mothers begging for food for their children. The leader might approach a storekeeper and demand a donation of flour or groceries. If the storekeeper failed to provide, the Mollies would enter the store and take what they wanted, warning the owner of dire consequences if the incident was reported.

While the Whiteboys were known to wear white linen frocks over their clothing, the Mollies blackened their faces with burnt cork. There are similarities – particularly in face-blackening and in the donning of women's garments – with the practice of mummery, in which festive days were celebrated by mummers who traveled from door to door demanding food, money, or drink as payment for performing. The ''Threshers'', the ''Peep o' Day Boys'', the ''Lady Rocks'' (deriving from Captain Rock and the Rockite movement), and the ''Lady Clares'' also sometimes disguised themselves as women. Similar imagery was used during the Rebecca Riots

The Rebecca Riots (Welsh: ''Terfysgoedd Beca'') took place between 1839 and 1843 in West and Mid Wales. They were a series of protests undertaken by local farmers and agricultural workers in response to levels of taxation. The rioters, often me ...

in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

.

British and Irish newspapers reported about the Mollies in Ireland in the nineteenth century. Thomas Campbell Foster in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' on 25 August 1845 traced the commencement of "Molly Maguireism" to Lord Lorton ejecting tenants in Ballinamuck, County Longford, in 1835. An "Address of 'Molly Maguire' to her children" containing twelve rules was published in ''Freeman's Journal

The ''Freeman's Journal'', which was published continuously in Dublin from 1763 to 1924, was in the nineteenth century Ireland's leading nationalist newspaper.

Patriot journal

It was founded in 1763 by Charles Lucas and was identified with rad ...

'' on 7 July 1845. The person making the address claimed to be "Molly Maguire" of "Maguire's Grove, Parish of Cloone", in County Leitrim

County Leitrim ( ; gle, Contae Liatroma) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Connacht and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the village of Leitrim. Leitrim County Council is the local authority for the ...

. The rules advised Mollies about how they should conduct themselves in land disputes and were an attempt to direct the movement's activities:

* Keep strictly to the land question, by allowing no landlord more than fair value for his tenure.

* No Rent to be paid until harvest.

* Not even then without an abatement, where the land is too high.

* No undermining of tenants, nor bailiff's fees to be paid.

* No turning out of tenants, unless two years rent due before ejectment served.

* Assist to the utmost of your power the good landlord, in getting his rents.

* Cherish and respect the good landlord, and good agent.

* Keep from travelling by night.

* Take no arms by day, or by night, from any man, as from such acts a deal of misfortune springs, having, I trust you have, more arms than you ever will have need for.

* Avoid coming in contact with either the military, or police; they are only doing what they cannot help.

* For my sake, then, no distinction to any man, on account of his religion; his acts alone you are to look to.

* Let bygones be bygones, unless in a very glaring case; but watch for the time to come.

In Liverpool

The Molly Maguires were also active inLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, where many Irish people settled in the 19th century, and many more passed through Liverpool on their way to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

or Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. The Mollies are first mentioned in Liverpool in an article in ''The Liverpool Mercury'' newspaper on 10 May 1853. The newspaper reported that, "a regular faction fight took place in Marybone amongst the Irish residents in that district. About 200 men and women assembled, who were divided into four parties – the 'Molly Maguires', the 'Kellys', the 'Fitzpatricks' and the 'Murphys' – the greater number of whom were armed with sticks and stones. The three latter sections were opposed to the 'Molly Maguires' and the belligerents were engaged in hot conflict for about half an hour, when the guardians of the peace interfered."

Later Liverpool newspaper articles from the same time period refer to assaults by Mollies against other Irish Liverpudlians. The "Molly Maguire club" or "Molly's Club" was described as a "mutual defence association" that had been "formed for the mutual assistance of the members when they got into 'trouble', each member subscribing to the funds". Patrick Flynn was the secretary of the Liverpool Molly Maguire Clubs in the 1850s and their headquarters was in an alehouse in Alexander Pope Street also known as Sawney Pope Street. The Liverpool branch of the Molly Maguires was known for its gangsterism rather than any genuine concern for the welfare of Irish people.Molly Maguirespolitics.ie; accessed 8 September 2015.

In the United States

The Mollies are believed to have been present in the anthracite coal fields ofPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in the United States since at least the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

until becoming largely inactive following a series of arrests, trials and executions, between 1876 and 1878. Members of the Mollies were accused of murder, arson, kidnapping and other crimes, in part based on allegations by Franklin B. Gowen

Franklin Benjamin Gowen (February 9, 1836 – December 13, 1889) served as president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad (commonly referred to as the Reading Railroad) in the 1870s/80s. He is identified with the undercover infiltration an ...

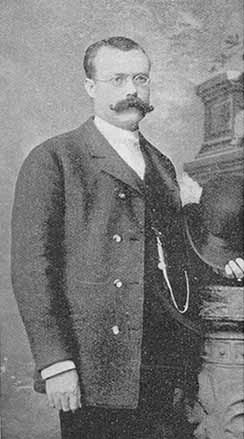

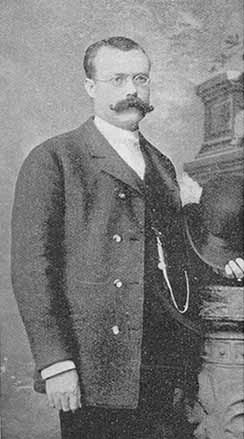

and the testimony of a Pinkerton detective, James McParland

James McParland (''né'' McParlan; 1844, County Armagh, Ireland – 18 May 1919, Denver, Colorado) was an American private detective and Pinkerton agent.

McParland arrived in New York in 1867. He worked as a laborer, policeman and then in Chica ...

(also known as ''James McKenna''), a native of County Armagh, Ireland. Fellow prisoners testified against the defendants, who were arrested by the Coal and Iron Police

The Coal and Iron Police was a private police force in the US state of Pennsylvania that existed between 1865 and 1931. It was established by the Pennsylvania General Assembly but employed and paid by the various coal companies. The origins of the ...

. Gowen acted as a prosecutor in some of the trials.

The trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

seem to have focused almost exclusively upon the Molly Maguires for criminal prosecution. Information passed from the Pinkerton detective, intended only for the detective agency and their client – the most powerful industrialist of the region – was also provided to vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

s who ambushed and murdered miners suspected of being Molly Maguires, as well as their families.Horan, pp. 151-52. Molly Maguire history is sometimes presented as the prosecution of an underground movement that was motivated by personal vendettas, and sometimes as a struggle between organized labor and powerful industrial forces. Whether membership in the Mollies' society overlapped union membership to any appreciable extent remains open to conjecture.

Some historians (such as Philip Rosen, former curator of the Holocaust Awareness Museum of the Delaware Valley) believe that Irish immigrants brought a form of the Molly Maguires organization into America in the 19th century, and continued its activities as a clandestine society. They were located in a section of the anthracite coal fields dubbed the Coal Region

The Coal Region is a region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is known for being home to the largest known deposits of anthracite coal in the world with an estimated reserve of seven billion short tons.

The region is typically defined as compri ...

, which included the Pennsylvania counties of Lackawanna, Luzerne, Columbia, Schuylkill, Carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

, and Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

. Irish miners in this organization employed the tactics of intimidation and violence used against Irish landlords during the "Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

s" yet again in violent confrontations against the anthracite, or ''hard coal'', mining companies in the 19th century.

Historians' disagreement

A legal self-help organization for Irish immigrants existed in the form of theAncient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in N ...

(AOH), but it is generally accepted that the Mollies existed as a secret organization in Pennsylvania, and used the AOH as a front. However, Joseph Rayback

Joseph G. Rayback (1914–1983) was a professor of history in the United States.

Career

He served in the United States Navy and earned a Ph.D. in American history at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. For many years, he was a p ...

's 1966 volume, ''A History of American Labor'', claims the "identity of the Molly Maguires has never been proved". Rayback writes:

Authors who accept the existence of the Mollies as a violent and destructive group acknowledge a significant scholarship that questions the entire history. In ''The Pinkerton Story'', authors James D. Horan and Howard Swiggett write sympathetically about the detective agency and its mission to bring the Mollies to justice. They observe:

History

During the mid-19th century, hard coal mining came to dominate northeastern Pennsylvania, a region already deforested twice over to feed America's growing need for energy. By the 1870s, powerful financial syndicates controlled the railroads and the coalfields. Coal companies had begun to recruit immigrants from overseas willing to work for less than the prevailing local wages paid to American-born employees, luring them with "promises of fortune-making". Herded into freight trains by the hundreds, these workers often replaced English-speaking miners who, according to labor historian George Korson: The immigrant workers: About 22,000 coal miners worked in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. 5,500 of these were children between the ages of seven and sixteen years, who earned between one and three dollars a week separating slate from the coal. Injured miners, or those too old to work at the face, were assigned to picking slate at the "breakers" where the coal was crushed into a manageable size. Thus, many of the elderly miners finished their mining days as they had begun in their youth.Boyer and Morais, pp. 51-52. The miners lived a life of "bitter, terrible struggle".Horan, p. 125.Disaster strikes

Wages were low, working conditions were atrocious, and deaths and serious injuries numbered in the hundreds each year. On 6 September 1869, a fire at the Avondale Mine in Luzerne County, took the lives of 110 coal miners. The families blamed the coal company for failing to finance a secondary exit for the mine. The miners faced a speedup system that was exhausting. In its November 1877 issue, '' Harper's New Monthly Magazine'' published an interviewer's comments: "A miner tells me that he often brought his food uneaten out of the mine from want of time; for he must have his car loaded when the driver comes for it, or lose one of the seven car-loads which form his daily work." As the bodies of the miners were brought up from the Avondale Mine disaster, John Siney, head of the Workingmen's Benevolent Association (WBA), climbed onto a wagon to speak to the thousands of miners who had arrived from surrounding communities:Boyer and Morais, p. 45. Siney asked the miners to join the union, and thousands did so that day. Some miners faced additional burdens of prejudice and persecution. In the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s, some 20,000 Irish workers had arrived in Schuylkill County. It was a time of rampant beatings and murders in the mining district.Panic of 1873

1873-79 (seePanic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

) were marked by one of the worst depressions in the nation's history, caused by economic overexpansion, a stock market crash, and a decrease in the money supply. By 1877 an estimated one-fifth of the nation's workingmen were completely unemployed, two-fifths worked no more than six or seven months a year, and only one-fifth had full-time jobs. Labor organizers angrily watched railway directors riding about the country in luxurious private cars while proclaiming their inability to pay living wages to hungry working men.Horan, p. 127.

Mine owners move against the union

Franklin B. Gowen

Franklin Benjamin Gowen (February 9, 1836 – December 13, 1889) served as president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad (commonly referred to as the Reading Railroad) in the 1870s/80s. He is identified with the undercover infiltration an ...

, the president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railway

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and commercial rail transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states that operated from 1924 until its 1976 acquisition by Conrail.

Commonly called ...

, and of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company

Reading Anthracite Company is a coal mining company based in Pottsville, Pennsylvania in the United States. It mainly mines anthracite coal in the Coal Region of eastern Pennsylvania.

The company owns the Bear Valley Strip Mine in Northumberland ...

and "the wealthiest anthracite coal mine owner in the world", hired Allan Pinkerton

Allan J. Pinkerton (August 25, 1819 – July 1, 1884) was a Scottish cooper, abolitionist, detective, and spy, best known for creating the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the United States and his claim to have foiled a plot in 1861 to a ...

's services to deal with the Mollies. Pinkerton selected James McParland

James McParland (''né'' McParlan; 1844, County Armagh, Ireland – 18 May 1919, Denver, Colorado) was an American private detective and Pinkerton agent.

McParland arrived in New York in 1867. He worked as a laborer, policeman and then in Chica ...

(sometimes called McParlan), a native of County Armagh, to go undercover against the Mollies. Using the alias "James McKenna", he made Shenandoah his headquarters and claimed to have become a trusted member of the organization. His assignment was to collect evidence of murder plots and intrigue, passing this information along to his Pinkerton manager. He also began working secretly with a Pinkerton agent assigned to the Coal and Iron Police for the purpose of coordinating the eventual arrest and prosecution of members of the Molly Maguires. Although there had been fifty "inexplicable murders" between 1863 and 1867 in Schuylkill County, progress in the investigations was slow.Boyer and Morais, p. 51. There was "a lull in the entire area, broken only by minor shootings". McParland wrote: I am sick and tired of this thing. I seem to make no progress.Horan, p. 151.

The union had grown powerful; thirty thousand members — eighty-five percent of Pennsylvania's anthracite miners — had joined. But Gowen had built a combination of his own, bringing all of the mine operators into an employers' association known as the Anthracite Board of Trade. In addition to the railroad, Gowen owned two-thirds of the coal mines in southeastern Pennsylvania. He was a risk-taker and an ambitious man. Gowen decided to force a strike and showdown.

Union, Mollies, and Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH)

One of the burning questions for modern scholars is the relationship between the Workingmen's Benevolent Association (WBA), the Mollies, and their alleged cover organization, theAncient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in N ...

. Historian Kevin Kenny notes that the convicted men were all members of the AOH. But "the Molly Maguires themselves left virtually no evidence of their existence, let alone their aims and motivation." Relying upon his personal knowledge before commencing an investigation, McParland believed that the Molly Maguires, under pressure for their activities, had taken the new name, "The Ancient Order of Hibernians" (AOH). After beginning his investigation, he estimated that there were about 450 members of the AOH in Schuylkill County.Anthony Lukas, ''Big Trouble'', 1997, pp. 179, 182.

While Kenny observes that the AOH was "a peaceful fraternal society", he does note that in the 1870s the Pinkerton Agency identified a correlation between the areas of AOH membership in Pennsylvania, and the corresponding areas in Ireland from which those particular Irish immigrants emigrated. The violence-prone areas of Ireland corresponded to areas of violence in the Pennsylvania coalfields. In his book ''Big Trouble'', which traces McParland's history, writer J. Anthony Lukas has written: "The WBA was run by Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancash ...

men adamantly opposed to violence. But owensaw an opportunity to paint the union with the Molly brush, which he did in testimony before a state investigating committee ... 'I do not charge this Workingmen's Benevolent Association with it, but I say there is an association which votes in secret, at night, that men's lives shall be taken ... I do not blame this association, but I blame another association for doing it; and it happens that the only men who are shot are the men who dare disobey the mandates of the Workingmen's Benevolent Association.'"

Of the 450 AOH members that Pinkerton Agent McParland estimated were in Schuylkill County, about 400 belonged to the union. Molly Maguireism and full-fledged trade unionism represented fundamentally different modes of organization and protest. Kenny noted that one contemporary organization, the Pennsylvania Bureau of Industrial Statistics, clearly distinguished between the union and the violence attributed to the Molly Maguires. Their reports indicate that violence could be traced to the time of the Civil War, but that in the five-year existence of the WBA, "the relations existing between employers and employees" had greatly improved. The Bureau concluded that the union had brought an end to the "carnival of crime". Kenny notes the leaders of the WBA were "always unequivocally opposed" to the Molly Maguires.

Kenny notes there were frequent tensions between miners of English and Welsh descent, who held the majority of skilled positions, and the mass of unskilled Irish laborers. However, in spite of such differences, the WBA offered a solution, and for the most part "did a remarkable job" in overcoming such differences.

Vigilante justice

F.P. Dewees, a contemporary and a confidant of Gowen, wrote that by 1873 "Mr. Gowen was fully impressed with the necessity of lessening the overgrown power of the 'Labor Union' and exterminating if possible the Molly Maguires." In December, 1874, Gowen led the other coal operators to announce a twenty percent pay cut. The miners decided to strike on 1 January 1875. A Pinkerton agent, Robert J. Linden, was brought in to support McParland while serving with the Coal and Iron Police. On 29 August 1875, Allan Pinkerton wrote a letter to George Bangs, Pinkerton's general superintendent, recommending vigilante actions against the Molly Maguires: "The M.M.'s are a species of Thugs... Let Linden get up a vigilance committee. It will not do to get many men, but let him get those who are prepared to take fearful revenge on the M.M.'s. I think it would open the eyes of all the people and then the M.M.'s would meet with their just deserts." On 10 December 1875, three men and two women were attacked in their home by masked men. Author Anthony Lukas wrote that the attack seemed "to reflect the strategy outlined in Pinkerton's memo". The victims had been secretly identified by McParland as Mollies. One of the men was killed in the house, and the other two supposed Mollies were wounded but able to escape. A woman, the wife of one of the reputed Mollies, was assassinated. McParland was outraged that the information he had been providing had found its way into the hands of indiscriminate killers. When McParland heard details of the attack at the house, he protested in a letter to his Pinkerton supervisor. He did not object that Mollies might be assassinated as a result of his labor spying – they "got their just deserving". McParland resigned when it became apparent the vigilantes were willing to commit the "murder of women and children", whom he deemed innocent victims. His letter stated: There appears to be an error in the detective's report (which also constituted his resignation letter) of the vigilante incident: he failed to convey the correct number of deaths. Two of the three men "were wounded but able to escape". In the note, McParland reported that these two had been killed by vigilantes. Such notes, possibly containing erroneous or as-yet-unverified information, were forwarded daily by Pinkerton operatives. The content was routinely made available to Pinkerton clients in typed reports. Pinkerton detective reports now in the manuscripts collection at the Lackawanna County Historical Society reveal that Pinkerton had been spying on miners for the mine owners in Scranton. Pinkerton operatives were required to send a report each day. The daily reports were typed by staff, and conveyed to the client for a ten dollar fee. Such a process was relied upon to "warrant the continuance of the operative's services". McParland believed his daily reports had been made available to the anti-Molly vigilantes. Benjamin Franklin, McParland's Pinkerton supervisor, declared himself "anxious to satisfy cParlandthat he Pinkerton Agency hasnothing to do with he vigilante murders. McParland was prevailed upon not to resign. Frank Wenrich, a first lieutenant with thePennsylvania National Guard

The Pennsylvania National Guard is one of the oldest and largest National Guards in the United States Department of Defense. It traces its roots to 1747 when Benjamin Franklin established the Associators in Philadelphia.

With more than 18,000 pe ...

, was arrested as the leader of the vigilante attackers, but released on bail. Another miner, Hugh McGeehan, a 21-year-old who had been secretly identified as a killer by McParland, was fired upon and wounded by unknown assailants. Later, the McGeehan family's house was attacked by gunfire.

The strike fails

The union was nearly broken by the imprisonment of its leadership and by attacks conducted by vigilantes against the strikers. Gowen "deluged the newspapers with stories of murder and arson" committed by the Molly Maguires. The press produced stories of strikes in Illinois, in Jersey City, and in the Ohio mine fields, all inspired by the Mollies. The stories were widely believed. In Schuylkill County, the striking miners and their families were starving to death. A striker wrote to a friend: Since I last saw you, I have buried my youngest child, and on the day before its death there was not one bit of victuals in the house with six children.Boyer and Morais, p. 52. Andrew Roy in his book ''A History of the Coal Miners of the United States''Andrew Roy/ref> noted: After six months, the strike was defeated and the miners returned to work, accepting the 20 percent cut in pay. But miners belonging to the Ancient Order of Hibernians continued the fight. McParland acknowledged increasing support for the Mollies in his reports: Men, who last winter would not notice a Molly Maguire, are now glad to take them by the hand and make much of them. If the bosses exercise tyranny over the men they appear to look to the association for help. Lukas observes that the defeat was humiliating, and traces the roots of violence by the Mollies in the aftermath of the failed strike: Judges, lawyers, and policemen were overwhelmingly Welsh, German, or English ... When the coalfield Irish sought to remedy their grievances through the courts, they often met delays, obfuscation, or doors slammed in their faces. No longer looking to these institutions for justice, they turned instead to the Mollies.... Before the summer was over, six men—all Welsh or German—paid with their lives. Authors Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais argue that the killings were not one-sided:

McParland penetrates the "inner circle"

After months of little progress, McParland reported some plans by the "inner circle". Gomer James, a Welshman, had shot and wounded one of the Mollies, and plans were formulated for a revenge killing. But the wheels of revenge were grinding slowly. And there was other violence: A plan to destroy a railroad bridge was abandoned due to the presence of outsiders. The Irish miners had been forbidden to set foot in the public square in Mahanoy City, and a plan to occupy it by force of arms was considered then abandoned. In the meantime a messenger reported that .M.Thomas, the would-be killer of one of the Mollies, had been killed in the stable where he worked. McParland himself had been asked to supply the hidden killers with food and whiskey, according to the detective. According to Horan and Swiggett: Another plan was in the works, this one against two night watchmen, Pat McCarron and Benjamin K. Yost, a Tamaqua Borough Patrolman. Jimmy Kerrigan and Thomas Duffy were said to despise Yost, who had arrested them on numerous occasions. Yost was shot as he put out a street light, which at that time necessitated climbing the lamp pole. Before he died, he reported that his killers were Irish, but were not Kerrigan or Duffy. McParland recorded that a Mollie named William Love had killed a Justice of the Peace, surnamed Gwyther, in Girardville. Unknown Mollies were accused of wounding a man outside his saloon in Shenandoah. Gomer James was killed while tending bar. Then, McParland recorded, a group of Mollies reported to him that they had killed a mine boss named Sanger, and another man who was with him. Forewarned of the attempt, McParland had sought to arrange protection for the mine boss, but was unsuccessful.The trials

When Gowen first hired the Pinkerton agency, he had claimed the Molly Maguires were so powerful they had made powerful financial sources and organized labor "their puppets". When the trials of the alleged puppet-masters opened, Gowen had himself appointed as special prosecutor. The first trials were for the killing of John P. Jones. The three defendants, Michael J. Doyle, Jimmy Kerrigan and Edward Kelly, had elected to receive separate trials. Doyle went first, with his trial beginning 18 January 1876, and a conviction for first-degree murder being returned on 1 February. Before the trial completed, Kerrigan had decided to become a state's witness and gave details about the murders of Jones and Yost. Kelly's trial began on 27 March, and ended in conviction on 6 April 1876. The first trial of defendants McGeehan, Carroll, Duffy, James Boyle, and James Roarity for the killing of Yost commenced in May 1876. Yost had not recognized the men who attacked him. Although Kerrigan has since been described, along with Duffy, as hating the night watchman enough to plot his murder, Kerrigan became a state's witness and testified against the union leaders and other miners. However, Kerrigan's wife testified in the courtroom that her husband had committed the murder. She testified that she refused to provide her husband with clothing while he was in prison, because he had "picked innocent men to suffer for his crime". She stated that she was speaking out voluntarily, and was only interested in telling the truth about the murder. Gowen cross-examined her, but could not shake her testimony. Others supported her testimony amid speculation that Kerrigan was receiving special treatment due to the fact that McParland was engaged to his sister-in-law, Mary Ann Higgins. This trial was declared a mistrial due to the death of one of the jurors. A new trial was granted two months later. During that trial Fanny Kerrigan did not testify. The five defendants were sentenced to death. Kerrigan was allowed to go free.

The trial of Tom Munley for the murders of Thomas Sanger, a mine foreman, and William Uren, relied entirely on the testimony of McParland, and the eyewitness account of a witness. The witness stated under oath that he had seen the murderer clearly, and that Munley was not the murderer. Yet the jury accepted McParland's testimony that Munley had privately confessed to the murder. Munley was sentenced to death. Another four miners were put on trial and were found guilty on a charge of murder. McParland had no direct evidence, but had recorded that the four admitted their guilt to him. Kelly was being held in a cell for murder, and he was reputedly quoted as saying: "I would squeal on Jesus Christ to get out of here." In return for his testimony, the murder charge against him was dismissed.

In November, McAllister was convicted. McParland's testimony in the Molly Maguires trials helped send ten men to the gallows. The defense attorneys repeatedly sought to portray McParland as an

However, Kerrigan's wife testified in the courtroom that her husband had committed the murder. She testified that she refused to provide her husband with clothing while he was in prison, because he had "picked innocent men to suffer for his crime". She stated that she was speaking out voluntarily, and was only interested in telling the truth about the murder. Gowen cross-examined her, but could not shake her testimony. Others supported her testimony amid speculation that Kerrigan was receiving special treatment due to the fact that McParland was engaged to his sister-in-law, Mary Ann Higgins. This trial was declared a mistrial due to the death of one of the jurors. A new trial was granted two months later. During that trial Fanny Kerrigan did not testify. The five defendants were sentenced to death. Kerrigan was allowed to go free.

The trial of Tom Munley for the murders of Thomas Sanger, a mine foreman, and William Uren, relied entirely on the testimony of McParland, and the eyewitness account of a witness. The witness stated under oath that he had seen the murderer clearly, and that Munley was not the murderer. Yet the jury accepted McParland's testimony that Munley had privately confessed to the murder. Munley was sentenced to death. Another four miners were put on trial and were found guilty on a charge of murder. McParland had no direct evidence, but had recorded that the four admitted their guilt to him. Kelly was being held in a cell for murder, and he was reputedly quoted as saying: "I would squeal on Jesus Christ to get out of here." In return for his testimony, the murder charge against him was dismissed.

In November, McAllister was convicted. McParland's testimony in the Molly Maguires trials helped send ten men to the gallows. The defense attorneys repeatedly sought to portray McParland as an agent provocateur

An agent provocateur () is a person who commits, or who acts to entice another person to commit, an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation of, or entice legal action against, th ...

who was responsible for not warning people of their imminent deaths. For his part, McParland testified that the AOH and the Mollies were one and the same, and the defendants guilty of the murders. In 1905, during the Colorado Labor Wars

The Colorado Labor Wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the U.S. state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of m ...

, in preparation for a trial, McParland told another witness, Harry Orchard

Albert Edward Horsley (March 18, 1866 – April 13, 1954), best known by the pseudonym Harry Orchard, was a miner convicted of the 1905 political assassination of former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. The case was one of the most sensational an ...

, that "Kelly the Bum" not only had won his freedom for testifying against union leaders, he had been given $1,000 to "subsidize a new life abroad". McParland had been attempting to convince Orchard to accuse Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

, leader of the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

(WFM), of conspiracy to commit another murder. Unlike the Mollies, the WFM's union leadership was acquitted. Orchard alone was convicted, and spent the rest of his life in prison.

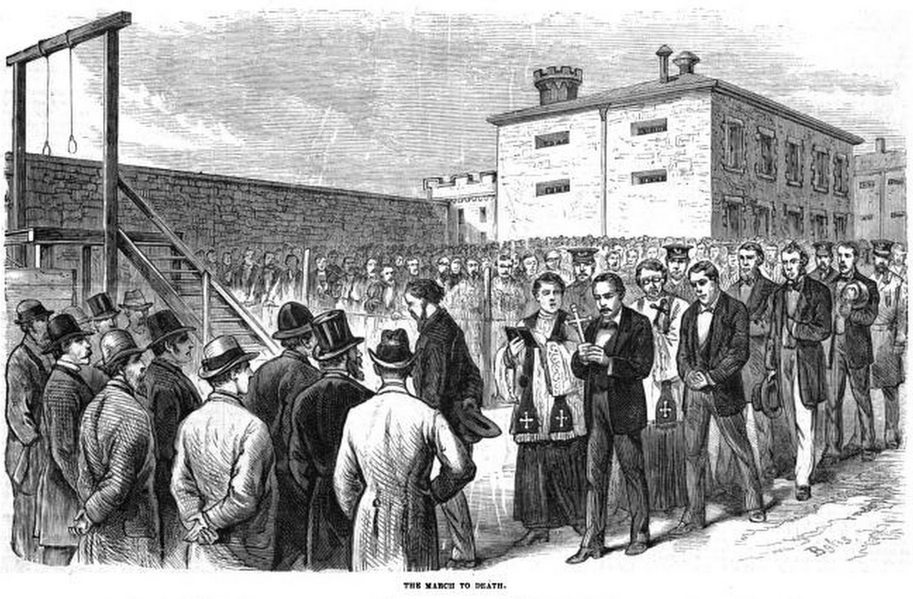

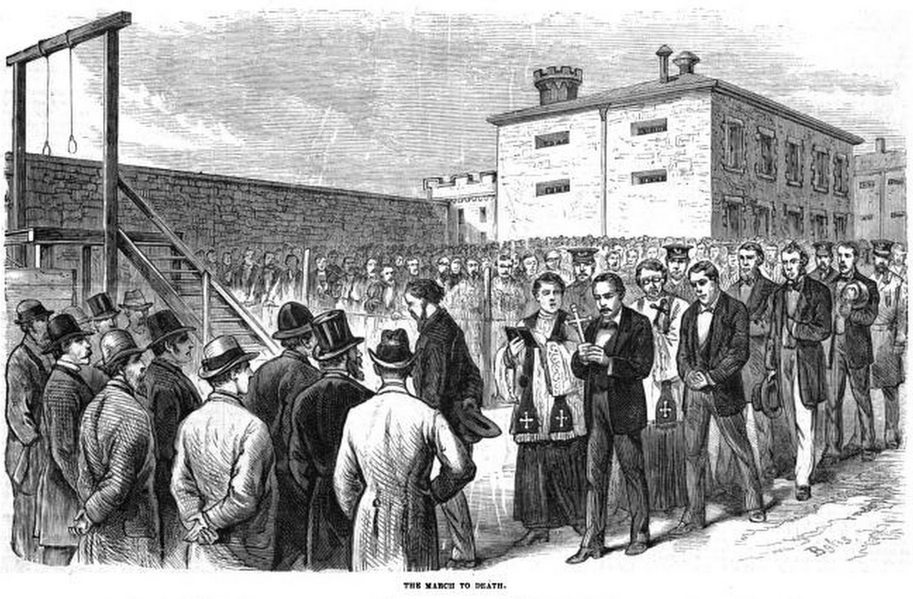

The executions

On 21 June 1877, six men were hanged in the prison at Pottsville, and four at Mauch Chunk, Carbon County. A scaffold had been erected in the Carbon County Jail. State militia with fixed bayonets surrounded the prisons and the scaffolds. Miners arrived with their wives and children from the surrounding areas, walking through the night to honor the accused, and by nine o'clock "the crowd in Pottsville stretched as far as one could see." The families were silent, which was "the people's way of paying tribute" to those about to die. Thomas Munley's aged father had walked more than from Gilberton to assure his son that he believed in his innocence. Munley's wife arrived a few minutes after they closed the gate, and they refused to open it even for close relatives to say their final good-byes. She screamed at the gate with grief, throwing herself against it until she collapsed, but she was not allowed to pass. Four ( Alexander Campbell, John "Yellow Jack" Donahue, Michael J. Doyle and Edward J. Kelly) were hanged on 21 June 1877, at a Carbon County prison in Mauch Chunk (renamed Jim Thorpe in 1953), for the murders of John P. Jones and Morgan Powell, both mine bosses, following a trial later described by a Carbon County judge, John P. Lavelle, as follows:

Campbell, just before his execution, allegedly slapped a muddy handprint on his cell wall stating "There is proof of my words. That mark of mine will never be wiped out. It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man." Doyle and Hugh McGeehan were led to the scaffold. They were followed by Thomas Munley, James Carroll, James Roarity, James Boyle, Thomas Duffy, Kelly, Campbell, and "Yellow Jack" Donahue. Judge Dreher presided over the trials. Ten more condemned, Thomas Fisher, John "Black Jack" Kehoe, Patrick Hester, Peter McHugh, Patrick Tully, Peter McManus, Dennis Donnelly, Martin Bergan, James McDonnell and Charles Sharpe, were hanged at Mauch Chunk, Pottsville, Bloomsburg and Sunbury over the next two years. Peter McManus was the last Molly Maguire to be tried and convicted for murder at the Northumberland County Courthouse in 1878. ''Note:'' This includes

On 21 June 1877, six men were hanged in the prison at Pottsville, and four at Mauch Chunk, Carbon County. A scaffold had been erected in the Carbon County Jail. State militia with fixed bayonets surrounded the prisons and the scaffolds. Miners arrived with their wives and children from the surrounding areas, walking through the night to honor the accused, and by nine o'clock "the crowd in Pottsville stretched as far as one could see." The families were silent, which was "the people's way of paying tribute" to those about to die. Thomas Munley's aged father had walked more than from Gilberton to assure his son that he believed in his innocence. Munley's wife arrived a few minutes after they closed the gate, and they refused to open it even for close relatives to say their final good-byes. She screamed at the gate with grief, throwing herself against it until she collapsed, but she was not allowed to pass. Four ( Alexander Campbell, John "Yellow Jack" Donahue, Michael J. Doyle and Edward J. Kelly) were hanged on 21 June 1877, at a Carbon County prison in Mauch Chunk (renamed Jim Thorpe in 1953), for the murders of John P. Jones and Morgan Powell, both mine bosses, following a trial later described by a Carbon County judge, John P. Lavelle, as follows:

Campbell, just before his execution, allegedly slapped a muddy handprint on his cell wall stating "There is proof of my words. That mark of mine will never be wiped out. It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man." Doyle and Hugh McGeehan were led to the scaffold. They were followed by Thomas Munley, James Carroll, James Roarity, James Boyle, Thomas Duffy, Kelly, Campbell, and "Yellow Jack" Donahue. Judge Dreher presided over the trials. Ten more condemned, Thomas Fisher, John "Black Jack" Kehoe, Patrick Hester, Peter McHugh, Patrick Tully, Peter McManus, Dennis Donnelly, Martin Bergan, James McDonnell and Charles Sharpe, were hanged at Mauch Chunk, Pottsville, Bloomsburg and Sunbury over the next two years. Peter McManus was the last Molly Maguire to be tried and convicted for murder at the Northumberland County Courthouse in 1878. ''Note:'' This includes

Rhodes's account of the Mollies

Many accounts of the Molly Maguires that were written during, or shortly after, the period offer no admission that there was widespread violence in the area, that vigilantism existed, nor that violence was carried out ''against'' the miners. In 1910, industrialist and historianJames Ford Rhodes

James Ford Rhodes (May 1, 1848 – January 22, 1927), was an American industrialist and historian born in Cleveland, Ohio. After earning a fortune in the iron, coal, and steel industries by 1885, he retired from business. He devoted his life to his ...

published a major scholarly analysis in the leading professional history journal:Originally published in ''American Historical Review'' (April 1910; copyright expired)

The aftermath

When organized labor helped electTerence V. Powderly

Terence Vincent Powderly (January 22, 1849 – June 24, 1924) was an American labor union leader, politician and attorney, best known as head of the Knights of Labor in the late 1880s. Born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, he was later elected mayor ...

as mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming V ...

two years after the Molly Maguire trials, the opposition vilified his team as the "Molly Maguire Ticket".

In 1979, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp

Milton Jerrold Shapp (born Milton Jerrold Shapiro; June 25, 1912 – November 24, 1994) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 40th governor of Pennsylvania from 1971 to 1979 and the first Jewish governor of Pennsylvania. H ...

granted a posthumous pardon to John "Black Jack" Kehoe after an investigation by the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons. The request for a pardon was made by one of Kehoe's descendants. John Kehoe had proclaimed his innocence until his death. The Board recommended the pardon after investigating Kehoe's trial and the circumstances surrounding it. Shapp praised Kehoe, saying the men called "Molly Maguires" were "martyrs to labor" and heroes in the struggle to establish a union and fair treatment for workers. And "... is impossible for us to imagine the plight of the 19th Century miners in Pennsylvania's anthracite region" and that it was Kehoe's popularity among the miners that led Gowen "'to fear, despise and ultimately destroy im".

In popular culture

* Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes novel ''The Valley of Fear

''The Valley of Fear'' is the fourth and final Sherlock Holmes novel by British writer Arthur Conan Doyle. It is loosely based on the Molly Maguires and Pinkerton agent James McParland. The story was first published in the ''Strand Magazine ...

'' is partly based on James McParland's infiltration of the Mollies.

* '' The Molly Maguires'', a feature film starring Richard Harris

Richard St John Francis Harris (1 October 1930 – 25 October 2002) was an Irish actor and singer. He appeared on stage and in many films, notably as Corrado Zeller in Michelangelo Antonioni's '' Red Desert'', Frank Machin in '' This Sporting ...

as James McParland

James McParland (''né'' McParlan; 1844, County Armagh, Ireland – 18 May 1919, Denver, Colorado) was an American private detective and Pinkerton agent.

McParland arrived in New York in 1867. He worked as a laborer, policeman and then in Chica ...

and Sean Connery as Molly leader Jack Kehoe was released in 1970.

* A 1965 episode of '' The Big Valley'' titled "Heritage" portrayed the Mollies as active at a fictitious mine in the Sierra in the 1870s, in which the Irish miners protest the use of Chinese laborers during a mine strike.

* George Korson, a folklorist and journalist, wrote several songs on the topic including his composition ''Minstrels of the Mine Patch'', which has a section on the Molly Maguires: "Coal Dust on the Fiddle".

* From 1909 to 1911, when the team was managed by Deacon McGuire, the baseball team

A team is a group of individuals (human or non-human) working together to achieve their goal.

As defined by Professor Leigh Thompson of the Kellogg School of Management, " team is a group of people who are interdependent with respect to inf ...

in Cleveland was sometimes called the "Cleveland Molly Maguires."

* Irish folk band The Dubliners

The Dubliners were an Irish folk band founded in Dublin in 1962 as The Ronnie Drew Ballad Group, named after its founding member; they subsequently renamed themselves The Dubliners. The line-up saw many changes in personnel over their fifty-ye ...

have a song called "Molly Maguires".

* The Irish Rovers

The Irish Rovers is a group of Irish musicians that originated in Toronto, Canada. Formed in 1963'Irish Rovers are Digging out those old Folk songs', By Ballymena Weekly Editor, Ballymena Weekly Telegraph, N. Ireland – 20 August 1964 and na ...

' song, "Lament for the Molly Maguires", is on their album ''Upon a Shamrock Shore''.

* The Molly Maguires are referenced by Dr. Donald "Ducky" Mallard in an episode of the American television series NCIS. The reference was made in the episode titled "Musical Chairs", which appeared in the 8th episode of the 17th season of the series.

See also

*Anti-Rent War

The Anti-Rent War (also known as the Helderberg War) was a tenants' revolt in upstate New York in the period 1839–1845. The Anti-Renters declared their independence from the manor system run by patroons, resisting tax collectors and successfu ...

*Battle of Blair Mountain

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest labor uprising in United States history and the largest armed uprising since the American Civil War. The conflict occurred in Logan County, West Virginia, as part of the Coal Wars, a series of early- ...

*Coal strike of 1902

The Coal strike of 1902 (also known as the anthracite coal strike) was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners struck for higher wages, shorter workdays, and the recognition of ...

*Coal Wars

The Coal Wars were a series of armed labor conflicts in the United States, roughly between 1890 and 1930. Although they occurred mainly in the East, particularly in Appalachia, there was a significant amount of violence in Colorado after the tu ...

*Colorado Labor Wars

The Colorado Labor Wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the U.S. state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of m ...

*Copper Country strike of 1913–1914

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish- ...

*Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894

The Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 was a five-month strike by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado, United States. It resulted in a victory for the union and was followed in 1903 by the Colorado Labor Wars. I ...

*Harlan County War

The Harlan County War, or Bloody Harlan, was a series of coal industry skirmishes, executions, bombings and strikes (both attempted and realized) that took place in Harlan County, Kentucky, during the 1930s. The incidents involved coal miners ...

* Illinois coal wars

* Mining in the United States

Mining in the United States has been active since the beginning of colonial times, but became a major industry in the 19th century with a number of new mineral discoveries causing a series of mining rushes. In 2015, the value of coal, metals, and i ...

* Scotch Cattle

Scotch Cattle was the name taken by bands of coal miners in 19th century South Wales, analogous to the Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires were an Irish people, Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool and parts of the Ea ...

, miners in 19th-century South Wales who would attack colleagues who worked during strikes.

* West Virginia coal wars

* List of worker deaths in United States labor disputes

Footnotes

Further reading

Contemporary sources

* Dewees, Francis P''The Molly Maguires: The Origin, Growth, and Character of the Organization.''

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1877. * Pinkerton, Allan; ''The Mollie Maguires and the Detectives''; New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Publishers, 1877.

Scholarly secondary sources

* Bimba, Anthony. ''The Molly Maguires''. New York: International Publishers, 1932. * Broehl, Jr., Wayne G. ''The Molly Maguires'', Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1964. * Gudelunas, Jr., William Anthony, and William G. Shade. ''Before the Molly Maguires: The Emergence of the Ethnoreligious Factor in the Politics of the Lower Anthracite Region: 1844-1872''. New York: Arno Press, 1976. * Foner, Phillip. ''A History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 1, From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor.'' New York: International Publishers, 1947. * Kenny, Kevin''Making Sense of the Molly Maguires''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. * Kenny, Kevin. "The Molly Maguires in Popular Culture", ''Journal of American Ethnic History,'' vol. 14, no. 4 (1995), pp. 27–46. * Kenny, Kevin. "The Molly Maguires and the Catholic Church", ''Labor History,'' vol. 36, no. 3 (1995), pp. 345–376. * Lens, Sidney. ''The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sitdowns.'' New York: Doubleday, 1973. * Morn, Frank. ''The Eye that Never Sleeps: A History of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.'' Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982. * Rayback, Joseph G. ''A History of American Labor.'' Rev. and exp. ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1974. {{ISBN, 1-299-50529-5

External links

Audio interview with Irish-American historian and author John Kearns about the Molly Maguires

A Selection of Links for Coal Mining, Mine Fires, & The Molly Maguires

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050208025352/http://www.pacoalhistory.com/history/mollies.html Mollies and Black Diamonds

''The Molly Maguires and the Detectives'' (1877)

Documents in the Hagley Library Digital Archives

Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania 19th century in Pennsylvania Mining in Pennsylvania History of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania Irish secret societies Irish-American culture in Pennsylvania Irish-American history Labor disputes in the United States Miners' labor disputes in the United States Mining in the United States