Mladen Stojanović on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mladen Stojanović ( sr-cyr, Младен Стојановић; 7 April 1896 – 1 April 1942) was a

Stojanović was the third child and the first son of

Stojanović was the third child and the first son of

Young Bosnia's activists regarded literature as indispensable to revolution, and most of them wrote poems, short stories, or critiques. Stojanović wrote poems, Bašić 1969, pp. 180–82 and read the works of Petar Kočić, Aleksa Šantić, Vladislav Petković Dis, Sima Pandurović, Milan Rakić, and later the works of Russian authors. Bašić 1969, pp. 15–16 In his final years at the gymnasium, he read

Young Bosnia's activists regarded literature as indispensable to revolution, and most of them wrote poems, short stories, or critiques. Stojanović wrote poems, Bašić 1969, pp. 180–82 and read the works of Petar Kočić, Aleksa Šantić, Vladislav Petković Dis, Sima Pandurović, Milan Rakić, and later the works of Russian authors. Bašić 1969, pp. 15–16 In his final years at the gymnasium, he read

In 1931, Stojanović was contracted to the Prijedor branch of the state railway company to provide healthcare for its employees. Bašić 1969, pp. 115–18 In 1936, he was contracted to an iron ore mining company in Ljubija, a town near Prijedor, and would visit the mining company clinic twice a week. Bašić 1969, pp. 67–74 He also taught hygiene at the gymnasium in Prijedor. Together with other intellectuals from the town, he gave lectures to the miners at their club in Ljubija. His lectures were usually about medical issues, but he also described the economic and social position of workers in more advanced countries. He socialised with the miners and treated their family members free of charge. He was very active socially, and also participated in sports. In 1932, he founded the tennis club of Prijedor, which continues to bear his name. Stojanović once bought new

In 1931, Stojanović was contracted to the Prijedor branch of the state railway company to provide healthcare for its employees. Bašić 1969, pp. 115–18 In 1936, he was contracted to an iron ore mining company in Ljubija, a town near Prijedor, and would visit the mining company clinic twice a week. Bašić 1969, pp. 67–74 He also taught hygiene at the gymnasium in Prijedor. Together with other intellectuals from the town, he gave lectures to the miners at their club in Ljubija. His lectures were usually about medical issues, but he also described the economic and social position of workers in more advanced countries. He socialised with the miners and treated their family members free of charge. He was very active socially, and also participated in sports. In 1932, he founded the tennis club of Prijedor, which continues to bear his name. Stojanović once bought new

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was  The Prijedor communists were keen to rescue Stojanović from his imprisonment, but their attempts to bribe the Ustaše to release him failed. They also considered storming the school in which he was kept. On 17 July, just after midnight, Stojanović asked a guard to let him go to the toilet on the first floor of the school. The guard let him go and followed closely behind him. When they were halfway down the stairs, Stojanović shouted "Fire!" as smoke came from a room on the second floor. During the commotion of the guards and hostages extinguishing the fire, Stojanović entered the toilet and escaped through the window. Bašić 1969, pp. 17–20 He went to the village of Orlovci, several kilometres from Prijedor, where he was accompanied by Rade Bašića young communist who had earlier escaped from the town. Bašić escorted Stojanović toward Mount Kozara ( high), north of the Prijedor plain. Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 9–15

After Stojanović's escape, the Ustaše arrested his wife, Mira. His son, Vojin, born in 1940, was cared for by Mira's former husband. Mira was released from prison after several months, and she and Vojin went to

The Prijedor communists were keen to rescue Stojanović from his imprisonment, but their attempts to bribe the Ustaše to release him failed. They also considered storming the school in which he was kept. On 17 July, just after midnight, Stojanović asked a guard to let him go to the toilet on the first floor of the school. The guard let him go and followed closely behind him. When they were halfway down the stairs, Stojanović shouted "Fire!" as smoke came from a room on the second floor. During the commotion of the guards and hostages extinguishing the fire, Stojanović entered the toilet and escaped through the window. Bašić 1969, pp. 17–20 He went to the village of Orlovci, several kilometres from Prijedor, where he was accompanied by Rade Bašića young communist who had earlier escaped from the town. Bašić escorted Stojanović toward Mount Kozara ( high), north of the Prijedor plain. Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 9–15

After Stojanović's escape, the Ustaše arrested his wife, Mira. His son, Vojin, born in 1940, was cared for by Mira's former husband. Mira was released from prison after several months, and she and Vojin went to

On the morning of 19 July 1941, Stojanović and Bašić arrived at the camp of the communists and their sympathisers who escaped from Prijedor, situated at Rajlića Kosa above the village of Malo Palančište. The news of Stojanović's escape soon spread throughout the Prijedor district. The group, mostly in the early twenties, enjoyed an increase in their credibility and esteem since a well-known and respected doctor had joined their camp. People from surrounding Serb villages brought food and other supplies to Stojanović and his young comrades. Stojanović gave speeches to the villagers, telling them to be prepared for an impending uprising and urging them to bring him rifles they were hiding in their homes. The camp at Rajlića Kosa was the first Partisan camp in the Kozara area.

Kozara, located in northern Bosanska Krajina and centred around Mount Kozara, covers about . In 1941, the area had a population of nearly 200,000 people. The villagers were mostly Serbs, and the towns in the areathe biggest of which was Prijedorhad a mixed Bosnian Muslim, Serb, and Croat population. Several villages were inhabited by

On the morning of 19 July 1941, Stojanović and Bašić arrived at the camp of the communists and their sympathisers who escaped from Prijedor, situated at Rajlića Kosa above the village of Malo Palančište. The news of Stojanović's escape soon spread throughout the Prijedor district. The group, mostly in the early twenties, enjoyed an increase in their credibility and esteem since a well-known and respected doctor had joined their camp. People from surrounding Serb villages brought food and other supplies to Stojanović and his young comrades. Stojanović gave speeches to the villagers, telling them to be prepared for an impending uprising and urging them to bring him rifles they were hiding in their homes. The camp at Rajlića Kosa was the first Partisan camp in the Kozara area.

Kozara, located in northern Bosanska Krajina and centred around Mount Kozara, covers about . In 1941, the area had a population of nearly 200,000 people. The villagers were mostly Serbs, and the towns in the areathe biggest of which was Prijedorhad a mixed Bosnian Muslim, Serb, and Croat population. Several villages were inhabited by

The leaders of the Kozara uprising assembled again on 10 September 1941, at the foot of Lisina. The five detachments of the Kozara Partisans were re-arranged into three companies, possessing 217 rifles altogether. At the end of September, the Kozara Partisans began attacking NDH and German troops, initially targeting weaker elements. These operations gave them military experience and they also captured weapons and ammunition from the enemy. More men joined the Partisans, and two more companies had been formed in Kozara by the end of October. The Partisans gained control over a number of villages. Terzić 1957, pp. 136–38 After a reorganization, Partisan units in Kozara were merged into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment in early November 1941. Stojanović was appointed commander of this detachment. By mid-November, it consisted of 670 men organised in six companies and armed with 510 rifles, 5

The leaders of the Kozara uprising assembled again on 10 September 1941, at the foot of Lisina. The five detachments of the Kozara Partisans were re-arranged into three companies, possessing 217 rifles altogether. At the end of September, the Kozara Partisans began attacking NDH and German troops, initially targeting weaker elements. These operations gave them military experience and they also captured weapons and ammunition from the enemy. More men joined the Partisans, and two more companies had been formed in Kozara by the end of October. The Partisans gained control over a number of villages. Terzić 1957, pp. 136–38 After a reorganization, Partisan units in Kozara were merged into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment in early November 1941. Stojanović was appointed commander of this detachment. By mid-November, it consisted of 670 men organised in six companies and armed with 510 rifles, 5  After the third counter-insurgency operation, a battalion of the Croatian Home Guard was stationed on Mrakovica, a peak in Kozara. Stojanović ordered an attack by five companies of the 2nd Krajina Detachment on the battalion, which began on 5 December 1941 at 5:30 am. The battle ended by 9:30 am with a decisive victory to the Partisans. Bašić 1969, pp. 120–21 They lost five men, while 78 Home Guards were killed and around 200 were captured. The Partisans seized 155 rifles, 12 light and 6 heavy machine guns, 4 mortars, 120 mortar rounds, and 19,000 rounds of

After the third counter-insurgency operation, a battalion of the Croatian Home Guard was stationed on Mrakovica, a peak in Kozara. Stojanović ordered an attack by five companies of the 2nd Krajina Detachment on the battalion, which began on 5 December 1941 at 5:30 am. The battle ended by 9:30 am with a decisive victory to the Partisans. Bašić 1969, pp. 120–21 They lost five men, while 78 Home Guards were killed and around 200 were captured. The Partisans seized 155 rifles, 12 light and 6 heavy machine guns, 4 mortars, 120 mortar rounds, and 19,000 rounds of

On 29 or 30 December 1941, Stojanović arrived in the area of Grmeč in western Bosanska Krajina, which was in the zone of responsibility of the 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment. Bokan 1988, pp. 299–303 This zone also included Drvar, where the uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina began. The military activities of the Partisans there diminished after the capture of Drvar by Italian troops on 25 September 1941. In the Italians' propaganda, they presented themselves as protectors of the Serbian people against the Ustaše. Groups of Serbs collaborated with the Italians. According to Karabegović, the Partisans of the 1st Krajina Detachment became more active after Pucar held a conference with their commanders on 15 December 1941, but this activity was still weak in northern parts of Grmeč. Stojanović went there to counter the Italian propaganda and to mobilise the Partisans against the Italians and their collaborators; he was accompanied by Karabegović.

According to the writer Branko Ćopić, who was a Partisan in Grmeč, Stojanović was greeted by a crowd of villagers and welcomed with the traditional

On 29 or 30 December 1941, Stojanović arrived in the area of Grmeč in western Bosanska Krajina, which was in the zone of responsibility of the 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment. Bokan 1988, pp. 299–303 This zone also included Drvar, where the uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina began. The military activities of the Partisans there diminished after the capture of Drvar by Italian troops on 25 September 1941. In the Italians' propaganda, they presented themselves as protectors of the Serbian people against the Ustaše. Groups of Serbs collaborated with the Italians. According to Karabegović, the Partisans of the 1st Krajina Detachment became more active after Pucar held a conference with their commanders on 15 December 1941, but this activity was still weak in northern parts of Grmeč. Stojanović went there to counter the Italian propaganda and to mobilise the Partisans against the Italians and their collaborators; he was accompanied by Karabegović.

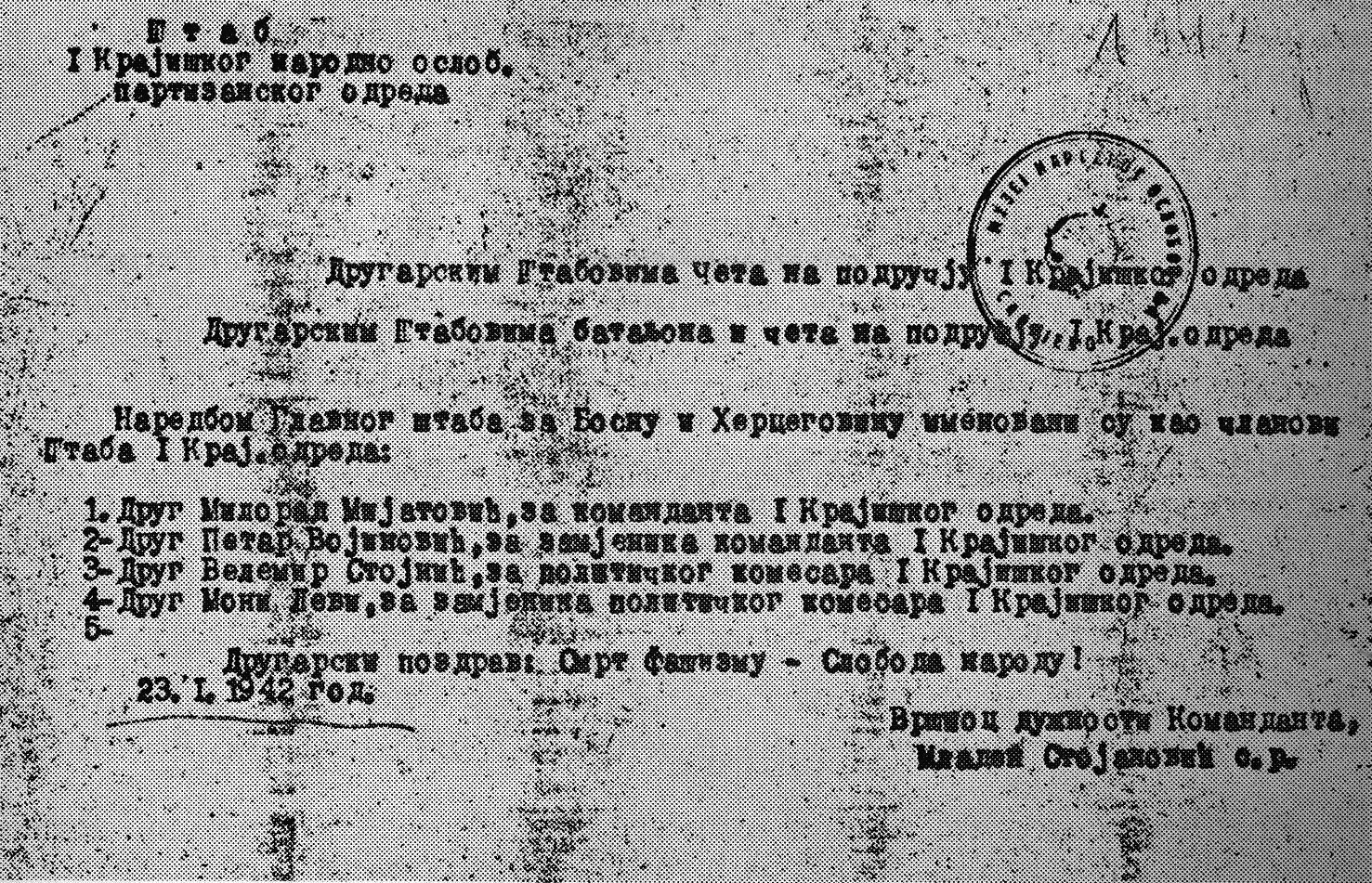

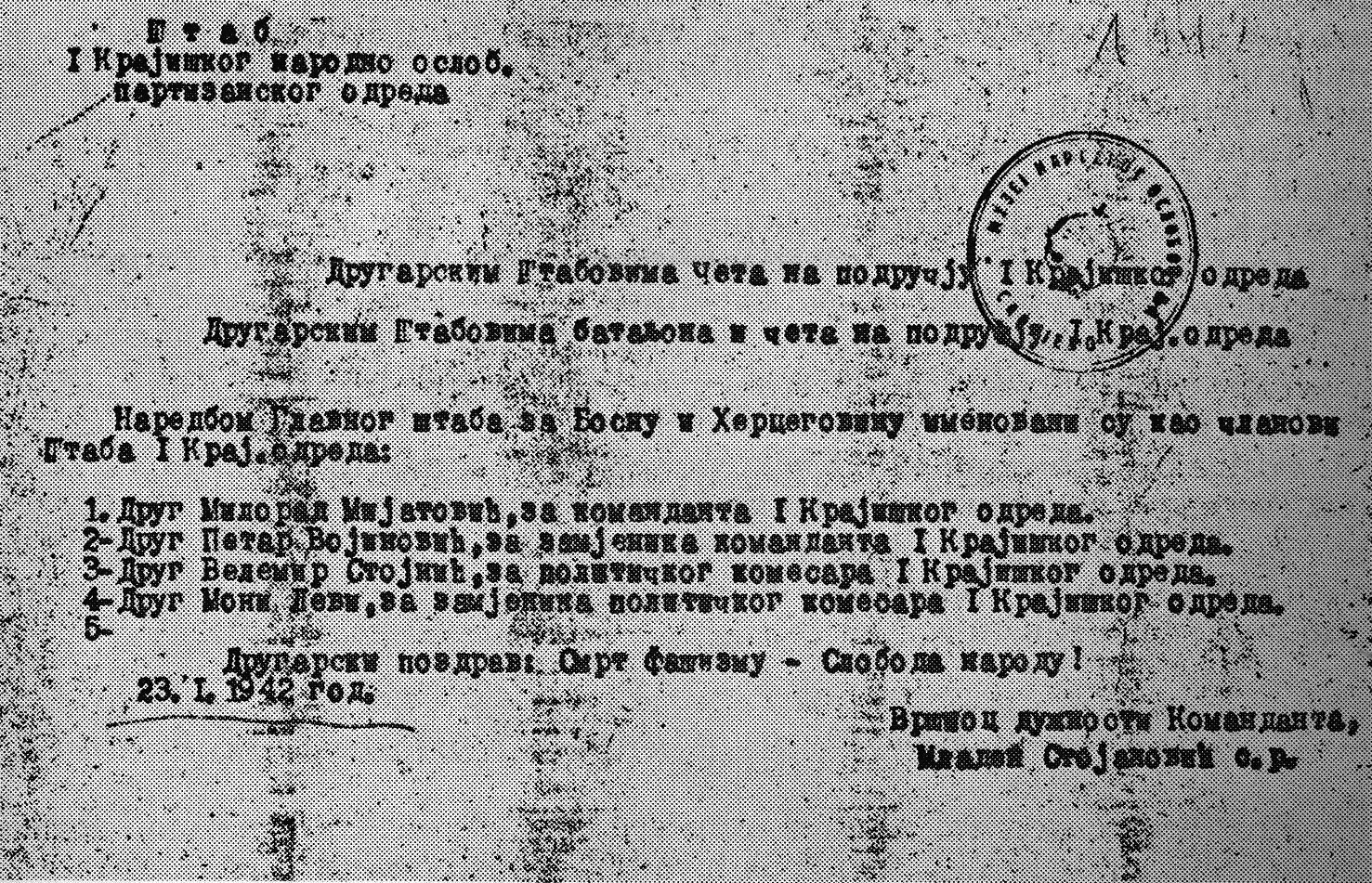

According to the writer Branko Ćopić, who was a Partisan in Grmeč, Stojanović was greeted by a crowd of villagers and welcomed with the traditional  On 22 January 1942, at the headquarters of the 1st Krajina Detachment in the village of Majkić Japra, Stojanović presided over a conference of the detachment staff and political activists of Grmeč. He criticised the detachment headquarters because it had no division of functions and there was no personal accountability among its members. He also stated the headquarters had no communication with the companies of the detachment, did not act as a military-political leadership, and there were no designated couriers available at all times at the headquarters. Stojanović was generally pleased with the Grmeč Partisans, describing them as courageous, enthusiastic, firm, and trustworthy but somewhat inexperienced. However, he said that the platoons of the detachment were dispersed in villages and had no contact with each other. In this way, according to Stojanović, the Partisans were losing their soldierly characteristics and becoming more like peasants. Stojanović criticised the views of some Partisans that political commissars should be abolished. He warned that the Partisans who wore emblems other than the

On 22 January 1942, at the headquarters of the 1st Krajina Detachment in the village of Majkić Japra, Stojanović presided over a conference of the detachment staff and political activists of Grmeč. He criticised the detachment headquarters because it had no division of functions and there was no personal accountability among its members. He also stated the headquarters had no communication with the companies of the detachment, did not act as a military-political leadership, and there were no designated couriers available at all times at the headquarters. Stojanović was generally pleased with the Grmeč Partisans, describing them as courageous, enthusiastic, firm, and trustworthy but somewhat inexperienced. However, he said that the platoons of the detachment were dispersed in villages and had no contact with each other. In this way, according to Stojanović, the Partisans were losing their soldierly characteristics and becoming more like peasants. Stojanović criticised the views of some Partisans that political commissars should be abolished. He warned that the Partisans who wore emblems other than the

Stojanović was in the field hospital for about 10 days before he was moved to a house around away. At the end of March 1942, the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina and the headquarters of the 4th Krajina Detachment were both located in Jošavka. The two headquarters and the field hospital were attacked on the night of 31 March by members of the Jošavka Partisan Company, who had joined the Chetnik side under the influence and leadership of Radoslav "Rade" Radić, the deputy commissar of the 4th Krajina Detachment. That night, the Chetniks killed 15 Partisans in Jošavka. Trikić & Rapajić 1982, pp. 71–73 According to Danica Perović, the physician who attended Stojanović, the Chetniks took his weapons and posted a sentry outside the house. Through a messenger, Radić told Stojanović to write a letter ordering Danko Mitrov to remove all Partisan units from the area around Jošavka. Stojanović, however, wrote a letter encouraging Mitrov to continue the Partisan fight. The next night, a group of Chetniks came to Stojanović, placed him on a blanket, and carried him out of the house. When they approached a nearby stream called Mlinska Rijeka, one of them shot Stojanović twice, killing him.

On 2 April, local villagers buried Stojanović on a steep, wooded hillside. By the end of April 1942, most of the companies of the 4th Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment had joined the Chetnik side or disintegrated. Rade Radić became the commander of the Chetnik detachments in Bosanska Krajina. After the war, Radić was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of Yugoslavia; he was executed by firing squad in 1945. Stojanović's remains were exhumed and reburied at Prijedor in November 1961. Bašić 1969, pp. 5–6

Stojanović was in the field hospital for about 10 days before he was moved to a house around away. At the end of March 1942, the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina and the headquarters of the 4th Krajina Detachment were both located in Jošavka. The two headquarters and the field hospital were attacked on the night of 31 March by members of the Jošavka Partisan Company, who had joined the Chetnik side under the influence and leadership of Radoslav "Rade" Radić, the deputy commissar of the 4th Krajina Detachment. That night, the Chetniks killed 15 Partisans in Jošavka. Trikić & Rapajić 1982, pp. 71–73 According to Danica Perović, the physician who attended Stojanović, the Chetniks took his weapons and posted a sentry outside the house. Through a messenger, Radić told Stojanović to write a letter ordering Danko Mitrov to remove all Partisan units from the area around Jošavka. Stojanović, however, wrote a letter encouraging Mitrov to continue the Partisan fight. The next night, a group of Chetniks came to Stojanović, placed him on a blanket, and carried him out of the house. When they approached a nearby stream called Mlinska Rijeka, one of them shot Stojanović twice, killing him.

On 2 April, local villagers buried Stojanović on a steep, wooded hillside. By the end of April 1942, most of the companies of the 4th Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment had joined the Chetnik side or disintegrated. Rade Radić became the commander of the Chetnik detachments in Bosanska Krajina. After the war, Radić was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of Yugoslavia; he was executed by firing squad in 1945. Stojanović's remains were exhumed and reburied at Prijedor in November 1961. Bašić 1969, pp. 5–6

On 19 April 1942, the headquarters of the 2nd Krajina Detachment changed its name to the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment "Mladen Stojanović". The Kozara Partisans vowed to avenge Stojanović's death on all the " enemies of the people". Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 22–23 The 2nd Krajina Detachment and four companies of the 1st Krajina Detachment liberated Prijedor on 16 May 1942. On 7 August 1942, the Partisans' supreme headquarters proclaimed Stojanović a People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

A monument to Stojanović was created by his brother Sreten after the war and erected in Prijedor. Streets, firms, schools, hospitals, pharmacies, and associations were named after Stojanović throughout socialist Yugoslavia, and songs were composed celebrating him as a hero. A Partisan film about him, titled '' Doktor Mladen'', was released in Yugoslavia in 1975. Stojanović was played by

On 19 April 1942, the headquarters of the 2nd Krajina Detachment changed its name to the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment "Mladen Stojanović". The Kozara Partisans vowed to avenge Stojanović's death on all the " enemies of the people". Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 22–23 The 2nd Krajina Detachment and four companies of the 1st Krajina Detachment liberated Prijedor on 16 May 1942. On 7 August 1942, the Partisans' supreme headquarters proclaimed Stojanović a People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

A monument to Stojanović was created by his brother Sreten after the war and erected in Prijedor. Streets, firms, schools, hospitals, pharmacies, and associations were named after Stojanović throughout socialist Yugoslavia, and songs were composed celebrating him as a hero. A Partisan film about him, titled '' Doktor Mladen'', was released in Yugoslavia in 1975. Stojanović was played by

Iza Sunca

' (''Behind the Sun''). In 1925, Stojanović initiated the creation of an anthology of Yugoslav lyric poetry. On this project, he worked with Feldman and

Gallery of photographs of Mladen Stojanović

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stojanovic, Mladen 1896 births 1942 deaths Deaths by firearm in Yugoslavia People from Prijedor People from the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina People killed by Chetniks during World War II Recipients of Austro-Hungarian royal pardons Recipients of the Order of the People's Hero Serbian military doctors Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina Yugoslav military doctors Yugoslav Partisans members Deaths by firearm in Bosnia and Herzegovina Prisoners and detainees of Austria-Hungary

Bosnian Serb

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби у Босни и Херцеговини, Srbi u Bosni i Hercegovini) are one of the three constitutive nations (state-forming nations) of the country, predominantly residing in the politi ...

and Yugoslav physician who led a detachment of Partisans on and around Mount Kozara in northwestern Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

during World War II in Yugoslavia

World War II in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia began on 6 April 1941, when the country was swiftly conquered by Axis forces and partitioned between Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and their client regimes. Shortly after Germany attacked the U ...

. He was posthumously bestowed the Order of the People's Hero

The Order of the People's Hero or the Order of the National Hero ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Orden narodnog heroja, Oрден народног хероја; sl, Red narodnega heroja, mk, Oрден на народен херој, Orden na ...

.

At the age of fifteen, Stojanović became an activist in a group of student organizations called Young Bosnia

Young Bosnia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Mlada Bosna, Млада Босна) was a separatist and revolutionary movement active in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary before World War I. Its members were predominantly ...

, which strongly opposed Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

's occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

. In 1912, Stojanović was inducted into ''Narodna Odbrana

Narodna Odbrana ( sr-cyr, Народна одбрана, literally, "The People's Defence" or "National Defence") was a Serbian nationalist organization established on October 8, 1908 as a reaction to the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and ...

'', an association founded in Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

with the goal of organizing guerrilla resistance to Bosnia-Herzegovina's annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

by Austria-Hungary. Stojanović was arrested by the Austro-Hungarian authorities in July 1914, and although he was sentenced to 16 years' imprisonment, he was pardoned in 1917. He graduated as a Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. ...

after World War I, and in 1929, opened a private practice in the town of Prijedor

Prijedor ( sr-cyrl, Приједор, ) is a city and municipality located in the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, it has a population of 89,397 inhabitants within its administrative limits. Prijedor is situated in ...

. In September 1940, he became a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, mk, Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, sl, Komunistična partija Jugoslavije mk ...

(KPJ).

Following the invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was ...

by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

and their creation of the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

, Stojanović was arrested at the behest of the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

, Croatia's fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

ruling party. He escaped prison and went to Kozara, where he joined fellow communists that had escaped from Prijedor. The KPJ chose Stojanović to lead the communist uprising in Prijedor. The uprising began on 30 July 1941, although neither Stojanović nor any of the other communists had much control over it at this stage. The Serb villagers of the district seized control of a number of villages and threatened Prijedor, which was defended by the Germans, Ustaše, and Croatian Home Guards. In August 1941, Stojanović was recognised as the principal leader of the Kozara insurgents, who were then organised into Partisan military units. Under Stojanović's direction, the Kozara Partisans began attacking the fascists from the end of September 1941. In early November 1941, all Partisan units in Kozara were merged into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment, commanded by Stojanović. By the end of the year, most of Kozaracovering about was controlled by Stojanović's detachment.

On 30 December 1941, Stojanović arrived in the Grmeč district, which was in the zone of responsibility of the 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment. The Italian troops operating in that area portrayed themselves as protectors of the Serb people. Stojanović's task was to counter such propaganda and mobilise the Partisans of the 1st Krajina Detachment to fight against the Italians. He stayed in the area until mid-February 1942, by which time the Partisan leadership of Bosnia-Herzegovina considered he had completed his tasks successfully. At the end of February 1942, Stojanović was appointed chief of staff of the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina—a unified command of all Partisan forces in the regions of Bosanska Krajina and central Bosnia. The Operational Headquarters' main task was to counter the rising influence of the Serb nationalist Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav royali ...

in those regions. On 5 March 1942, Stojanović was severely wounded in a Chetnik ambush. He was taken to a field hospital in the village of Jošavka. Members of the Jošavka Partisan Company defected to the Chetniks on the night of 31 March, and took Stojanović prisoner. The next night, a group of Chetniks killed him. In April 1942, the 2nd Krajina Detachment was named "Mladen Stojanović" in his honour, and a few months later he was posthumously awarded the Order of the People's Hero. After the war, his service to the Partisan cause was commemorated by the construction of a memorial in Prijedor, the naming of streets, public buildings and a park after him, in song and in film.

Early life

Stojanović was the third child and the first son of

Stojanović was the third child and the first son of Serbian Orthodox

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous ( ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.

The majority of the population ...

priest Simo Stojanović and his wife Jovanka. He was born in Prijedor on 7 April 1896. Bosnia-Herzegovina was then occupied by Austria-Hungary; Prijedor was located in Bosanska Krajina, the north-western region of the province. Bašić 1969, pp. 9–12 Stojanović's father was the third generation of his family to serve as a Serbian Orthodox priest. He had graduated from a theology faculty, becoming the first in the family to attain a higher level of education. Simo was active in the political struggle for ecclesiastical and educational autonomy for the Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Mladen Stojanović's maternal grandfather was a Serbian Orthodox priest from Dubica, Teodor Vujasinović; he had participated in Pecija's revolt against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

.

Stojanović completed his elementary education at the Serbian Elementary School in Prijedor in 1906. In 1907, he finished the first grade of his secondary education at the gymnasium in Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

, before he entered the gymnasium in Tuzla

Tuzla (, ) is the third-largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the administrative center of Tuzla Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, it has a population of 110,979 inhabitants.

Tuzla is the economic, cultural, e ...

, where he would complete the remaining seven grades. His brother Sreten Stojanovićwho would become a prominent sculptorjoined him at the Tuzla gymnasium in 1908.

Young Bosnia activist

Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina on 6 October 1908, which caused the Annexation Crisis in Europe. TheKingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia ( sr-cyr, Краљевина Србија, Kraljevina Srbija) was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Prin ...

protested and mobilised its army, but then on 31 March 1909, it formally accepted the annexation. In 1911, Mladen Stojanović became a member of the secret association of students of the Tuzla gymnasium called ''Narodno Jedinstvo'' (National Unity); its members described it as a youth society of nationalists. Bašić 1969, pp. 20–25 Dedijer 1966, pp. 580–83 It was one of a group of diverse student organisations later called Young Bosnia

Young Bosnia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Mlada Bosna, Млада Босна) was a separatist and revolutionary movement active in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary before World War I. Its members were predominantly ...

, which strongly opposed Austria-Hungary's rule over Bosnia-Herzegovina. The activists of Young Bosnia were Bosnian Serbs

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби у Босни и Херцеговини, Srbi u Bosni i Hercegovini) are one of the three constitutive nations (state-forming nations) of the country, predominantly residing in the politi ...

, Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, and Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, though most were Serbs. The first organisation regarded to be part of this group was established in 1904 by Serb students of the Mostar gymnasium. Dedijer 1966, pp. 293–98 1905 saw considerable political unrest among the Serb and Croat students of the Tuzla gymnasium. Although the provincial government imposed the name "Bosnian" on the language of the province (Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian () – also called Serbo-Croat (), Serbo-Croat-Bosnian (SCB), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS), and Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS) – is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia an ...

), the students demonstratively termed it as Serbian or Croatian depending on their ethnic affiliation.

Young Bosnia's activists regarded literature as indispensable to revolution, and most of them wrote poems, short stories, or critiques. Stojanović wrote poems, Bašić 1969, pp. 180–82 and read the works of Petar Kočić, Aleksa Šantić, Vladislav Petković Dis, Sima Pandurović, Milan Rakić, and later the works of Russian authors. Bašić 1969, pp. 15–16 In his final years at the gymnasium, he read

Young Bosnia's activists regarded literature as indispensable to revolution, and most of them wrote poems, short stories, or critiques. Stojanović wrote poems, Bašić 1969, pp. 180–82 and read the works of Petar Kočić, Aleksa Šantić, Vladislav Petković Dis, Sima Pandurović, Milan Rakić, and later the works of Russian authors. Bašić 1969, pp. 15–16 In his final years at the gymnasium, he read Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, Bakunin, Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his car ...

, Jaurès, Le Bon, Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

, and Marinetti. National Unity held meetings at which its members presented lectures and discussed current issues concerning the Serbian people of Bosnia-Herzegovina. All members of the association were Serbs. Generally, Stojanović's lectures were about educating people on practical issues of health and the economy. During the summer break of 1911, Stojanović travelled across Bosanska Krajina lecturing in villages. One of the aims of Young Bosnia was to eliminate the backwardness of their country.

In early-to-mid 1912, Stojanović and his schoolmate Todor Ilić joined ''Narodna Odbrana

Narodna Odbrana ( sr-cyr, Народна одбрана, literally, "The People's Defence" or "National Defence") was a Serbian nationalist organization established on October 8, 1908 as a reaction to the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and ...

'' (National Defence), an association founded in Serbia in December 1908 on the initiative of Branislav Nušić

Branislav Nušić ( sr-cyr, Бранислав Нушић, ; – 19 January 1938) was a Serbian playwright, satirist, essayist, novelist and founder of modern rhetoric in Serbia. He also worked as a journalist and a civil servant.

Life

Br ...

. It aimed to organise a guerrilla resistance to the Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and to spread nationalist propaganda. National Defence soon established a network of local committees throughout Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Its members from the latter territory gathered intelligence on the Austrian army and passed it to the Serbian secret service.

Stojanović and Ilić travelled illegally to Serbia during the summer break of 1912 to receive military training that National Defence organised for its members. They stayed for several days in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

, the capital of Serbia, where they met Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914.

Pr ...

, another activist of Young Bosnia who was also a member of National Defence. Stojanović and Ilić then spent a month at army barracks in Vranje

Vranje ( sr-Cyrl, Врање, ) is a city in Southern Serbia and the administrative center of the Pčinja District. The municipality of Vranje has a population of 83,524 and its urban area has 60,485 inhabitants.

Vranje is the economical, poli ...

in southern Serbia, undergoing military training under the command of Vojin Popović

Vojin Popović, known as Vojvoda Vuk ( sr, Војин Поповић, војвода Вук; 9 December 1881 – 29 November 1916) was a Serbian ''voivode'' (military commander), who fought for the Macedonian Serb Chetniks (i.e. komiti) in the ...

, a famous Chetnik

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

guerrilla fighter. When they returned to school, they resumed their activities with National Unity. Its members decided that Muslims should also be drawn into the association. After Trifko Grabež was expelled from the Tuzla gymnasium for slapping a teacher during a quarrel, the association organised a school strike. Most of the students who participated were Serbs; the strike gained little support among students of other ethnicities. The school took disciplinary measures against Ilić and Stojanović, who were regarded as the main organisers of the strike, and Ilić lost his scholarship.

In the autumn of 1913, Stojanović commenced the final year of his secondary education. National Unity was visited that year by a group of activists of Young Bosnia who were university students in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

. They held a series of lectures for the members of the association, explaining their views on the current political situation, and promoting the unity of South Slavic peoples in their struggle to liberate themselves from Austria-Hungary. These lectures influenced Stojanović to adopt a Yugoslavist stance. At the beginning of 1914, Ilić and Stojanović became, respectively, the president and the vice-president of National Unity, which numbered 34 members, including four Muslims and four Croats. Bašić 1969, pp. 36–40 At that time, National Unity was one of the most active groups of Young Bosnia.

According to Vid Gaković, who was a member of National Unity in 1914, Stojanović was an ambitious and talented young man. He was determined that his voice would be heard and he liked being the centre of attention. He was severe to younger members of the association, whom he sometimes sharply criticised. Nevertheless, younger students liked being around him. Gaković described him as a tall and handsome man who greatly cared about his appearance; he wore a bow tie and a broad-brimmed hat. Bašić 1969, pp. 49–52

On the morning of 28 June 1914, in Sarajevo, Princip assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

Fr ...

heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question. ...

to the throne of Austria-Hungaryand his wife Sophie

Sophie is a version of the female given name Sophia, meaning "wise".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Sophie of Thuringia, Duchess o ...

. Princip was a member of a group of conspirators, which included Trifko Grabež; the whole group was arrested by the Austrian police after the assassination. Blaming Serbia for the attack, Austria-Hungary declared war a month later, initiating World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Shortly after the assassination, Stojanović wrote in his notebook a quote from Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

: "There is no more sacred thing in the world than the duty of a conspirator, who becomes an avenger of humanity and the apostle of permanent natural laws." On 29 June, Stojanović took his final exams

A final examination, annual, exam, final interview, or simply final, is a test given to students at the end of a course of study or training. Although the term can be used in the context of physical training, it most often occurs in the a ...

at the Tuzla gymnasium. Soon afterwards, he and Ilić wrote a draft of their manifesto to South Slavic youth, referring to Young Bosnia in a sentence:

Vojislav Vasiljević, a close friend of Princip's, was a member of National Unity, and when the Austrian police searched his notebooks they found a list of members. Vasiljević kept this information as evidence of the payment of membership fees. All those on the list, including Stojanović, were arrested on 3 July 1914. Soon after, Stojanović's younger brother Sreten was arrested for anti-Austrian revolutionary correspondence between himself and Ilić. Beside the conspirators behind the assassination, six groups of activists of Young Bosnia were arrested. The group containing the members of National Unity was called the Tuzla group. The criminal investigation against them began on 9 July, and lasted for more than a year. They were kept in prisons in Tuzla, Banja Luka

Banja Luka ( sr-Cyrl, Бања Лука, ) or Banjaluka ( sr-Cyrl, Бањалука, ) is the second largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the largest city of Republika Srpska. Banja Luka is also the ''de facto'' capital of this entity. ...

, and Bihać. In the Banja Luka prison, they were all kept in the same room, enabling them to organise political and literary discussions. They issued a comic and satirical magazine, called "Mala paprika" (Little Paprika), the copies of which they made using carbon paper. A number of copies found their way out of the prison.

In the Bihać prison, the Tuzla group created a literary magazine named "Almanah" (Almanac). In its first and only issue, Mladen contributed several poems and an essay. Its editor-in-chief was Ilić, while Sreten Stojanović and Kosta Hakman contributed illustrations. The Stojanović brothers and Ilić learned French during their incarceration. The trial of the Tuzla group was held between 13 and 30 September 1915 in Bihać. Ilić was sentenced to death, Mladen to sixteen years' imprisonment, and the other members of the group received sentences between ten months and fifteen years. Especially aggravating for Ilić and Mladen was their participation in the 1912 military training in Serbia. The Austrians became aware of this because their army temporarily took Loznica in western Serbia at the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and there they found National Defence documents containing records of all Bosnians that attended the training.

Mladen and other members of the Tuzla group were sent to the prison in Zenica. Three months after they were sentenced they were joined by Ilić, whose death penalty had been commuted to 20 years' imprisonment. In the Zenica prison

The Zenica prison (''Kazneno-popravni zavod zatvorenog tipa Zenica'', ''KPZ Zenica'', ''K.P. DOM'', ''Zenička kaznionica'') is a closed-type prison located in Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was opened in 1886. It was the largest prison in Yu ...

, each convict had to spend the first three months in solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment in which the inmate lives in a single cell with little or no meaningful contact with other people. A prison may enforce stricter measures to control contraband on a solitary prisoner and use additi ...

. This was very hard on Mladen, who became mentally unwell and became so emaciated that Ilić could hardly recognise him. He recovered and took a course in shoe-making which was given in the prison. Afterwards, he fell seriously ill and had to undergo surgery in the prison hospital. Bašić 1969, pp. 61–65 In late 1917, the Austrian authorities pardoned all convicts of the Tuzla group except Ilić. Mladen went to his family in Prijedor. After a medical examination, he was declared unfit for army service due to his surgery and as a result was not drafted into the Austrian army. He entered the School of Medicine, University of Zagreb

The School of Medicine ( hr, Medicinski fakultet or MEF) in Zagreb is a Croatian medical school affiliated with the University of Zagreb. It is the oldest and biggest of the four medical schools in Croatia (the other three being in Osijek, Rije ...

, shortly before the disintegration of Austria-Hungary in November 1918.

Interwar period

TheKingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

renamed Yugoslavia in 1929was created on 1 December 1918, and incorporated Bosnia-Herzegovina. Stojanović continued studying medicine in Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

. As a former activist of Young Bosnia, he was offered a King's scholarship but he refused it. In Zagreb, he reunited with his former schoolmate Nikola Nikolić, who had also been a member of National Unity. After his release from the Zenica prison, Nikolić was drafted into the Austrian army and sent to the Russian front where he surrendered to the Russians and participated in the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

. Nikolić's account of the revolution influenced Stojanović to adopt a more leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

stance. During this period, Stojanović's favourite authors were Maksim Gorky and Miroslav Krleža. His professor of anatomy, Drago Perović, arranged for him to visit an anatomical institute in Vienna. Stojanović went there several times in 1921 and 1922 and befriended members of a leftist association of Yugoslav students at the Vienna University. Bašić 1969, pp. 87–89 When they held a protest against the king and government of Yugoslavia, Stojanović took part and delivered a speech. Behind the protest stood the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, mk, Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, sl, Komunistična partija Jugoslavije mk ...

(''Komunistička partija Jugoslavije'', KPJ). Bašić 1969, pp. 101–2

Stojanović graduated as a Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. ...

in 1926, and he worked for two years as a trainee physician in Zagreb and Sarajevo. He then opened a private practice in Pučišća

Pučišća (, it, Pucischie) is a coastal town and a municipality on the island of Brač in Croatia. It is often listed as one of the prettiest villages in Europe. It is known for its white limestone and beautiful bay. The town has a population ...

on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

island of Brač

Brač is an island in the Adriatic Sea within Croatia, with an area of ,

making it the largest island in Dalmatia, and the third largest in the Adriatic. It is separated from the mainland by the Brač Channel, which is wide. The island's tall ...

. In 1929, he returned to Prijedor, where he opened a practice on the first floor of the Stojanović family house, where his mother had lived alone since his father's death in 1926. Bašić 1969, pp. 107–12 Stojanović soon became a popular figure in Prijedor; his patients said that simply talking with him was curative. He treated poor people free of charge; he once sent a homeless man to a hospital in Zagreb and paid for his surgery. Stojanović earned well and had a good standard of living. Bašić 1969, pp. 93–95 People from other areas of Bosanska Krajina also went to him for medical treatment. In villages around Prijedor, where brawls were common, rowdies sang about him:

In 1931, Stojanović was contracted to the Prijedor branch of the state railway company to provide healthcare for its employees. Bašić 1969, pp. 115–18 In 1936, he was contracted to an iron ore mining company in Ljubija, a town near Prijedor, and would visit the mining company clinic twice a week. Bašić 1969, pp. 67–74 He also taught hygiene at the gymnasium in Prijedor. Together with other intellectuals from the town, he gave lectures to the miners at their club in Ljubija. His lectures were usually about medical issues, but he also described the economic and social position of workers in more advanced countries. He socialised with the miners and treated their family members free of charge. He was very active socially, and also participated in sports. In 1932, he founded the tennis club of Prijedor, which continues to bear his name. Stojanović once bought new

In 1931, Stojanović was contracted to the Prijedor branch of the state railway company to provide healthcare for its employees. Bašić 1969, pp. 115–18 In 1936, he was contracted to an iron ore mining company in Ljubija, a town near Prijedor, and would visit the mining company clinic twice a week. Bašić 1969, pp. 67–74 He also taught hygiene at the gymnasium in Prijedor. Together with other intellectuals from the town, he gave lectures to the miners at their club in Ljubija. His lectures were usually about medical issues, but he also described the economic and social position of workers in more advanced countries. He socialised with the miners and treated their family members free of charge. He was very active socially, and also participated in sports. In 1932, he founded the tennis club of Prijedor, which continues to bear his name. Stojanović once bought new kit

Kit may refer to:

Places

*Kitt, Indiana, US, formerly Kit

* Kit, Iran, a village in Mazandaran Province

* Kit Hill, Cornwall, England

People

* Kit (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Kit (surname)

Animals

* Young animal ...

for all members of the Rudar Ljubija football club. His contracts with the railway company and the mining company were both terminated in 1939. The railway employees protested in Prijedor, and Stojanović's contract with that company was subsequently renewed.

The Ljubija miners were on strike between 2 August and 8 September 1940. Some of the leaders of the strike were members of a secret KPJ cell in Ljubija, which was formed in January 1940. The KPJ had been outlawed in Yugoslavia since 1921. The KPJ organisation of Banja Luka sent its experienced member Branko Babič to help the strike leaders. Bašić 1969, pp. 76–80 According to Babič, a communist from Prijedor introduced him to Stojanović at the beginning of September 1940. Babič stayed for several days at the doctor's house, running the strike. Seeing Stojanović as a communist sympathiser, Babič proposed that he join the KPJ. Stojanović at first declined, saying that he still had bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. ...

habits, though he had read much of the Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

literature. After further conversations with Babič, Stojanović agreed to become a member of the party.

At the end of September 1940, Babič and all five members of the Ljubija cell held a meeting at which they unanimously decided to admit Stojanović into the KPJ. Babič held him in high esteem and regarded him as ardently devoted to the communist cause. Some communists, however, continued to refer to Stojanović as a communist sympathiser, and some regarded him as a "salon communist".

Onset of World War II

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

from all sides by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, led by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

forces. Vucinich 1949, pp. 355–358 Stojanović was assigned as a physician to an infantry battalion based in Banja Luka. For several days after the invasion this battalion moved toward Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, before it completely disintegrated without fighting the enemy, and Stojanović returned to Prijedor. Bašić 1969, pp. 43–44 The Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the land warfare military service branch of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (originally Kingdom of Serbs, ...

capitulated on 17 April, and the Axis powers proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Almost all of modern-day Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

, all of modern-day Bosnia-Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

, and parts of modern-day Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

were combined into a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

called the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

( hr, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH). It was an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate", which was controlled by the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

led by Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croatia ( hr, l ...

. One of its policies was to eliminate the ethnic Serb population of the NDH through mass killings, expulsions and forced assimilation, and many Serbs fled from the NDH to the German-occupied territory of Serbia

The Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia (german: Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien; sr, Подручје Војног заповедника у Србији, Područje vojnog zapovednika u Srbiji) was the area of the Kin ...

.

These repressive measures included taking prominent Serbs hostage against Serb attacks. To avoid being taken as a hostage, Stojanović paid 100,000 dinar

The dinar () is the principal currency unit in several countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and its historical use is even more widespread.

The modern dinar's historical antecedents are the gold dinar and the silver dirham, the main coin ...

s to the Ustaše in Prijedor. Resistance began to emerge in occupied Yugoslavia; royalists and Serbian nationalists under the leadership of then-Colonel Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Ar ...

founded the Ravna Gora Movement, whose members were called Chetniks. Vucinich 1949, pp. 362–365 Roberts 1987, pp. 20–22, 26 The KPJ, led by Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

, prepared to rise to arms at a favourable moment. Roberts 1987, pp. 23–24 In the view of the KPJ, the fight against the Axis and its domestic collaborators would be a common fight of all Yugoslav peoples.

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, began on 22 June 1941. Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, p. 152 On the same day, the Ustaše began arresting communists and their known sympathisers in the towns of Bosanska Krajina, including Prijedor. The communists had predicted this, and most of them avoided capture by escaping to the villages or hiding in the towns. Stojanović was one of the few communists arrested in Prijedor. Marjanović 1980, pp. 85–87 He was imprisoned with the Serb hostages on the second floor of a school in the town. They were subjected to forced labour, being led each morning through the town to repair the road to Kozarac

Kozarac ( sr-cyrl, Козарац, ) is a town in north-western Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, located near the city of Prijedor. It is located west of Banja Luka. Kozarac is also famous because of the Kozara National Park.

Kozarac ...

. The column of hostages was usually headed by Stojanović carrying a shovel on his shoulder. The Croatian Home Guards guarding the prison treated him well. While detained, Stojanović lectured a group of hostages about Marxism. Bašić 1969, pp. 53–57

On the day of the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, the Executive Committee of the Communist International

The Executive Committee of the Communist International, commonly known by its acronym, ECCI (Russian acronym ИККИ), was the governing authority of the Comintern between the World Congresses of that body. The ECCI was established by the Founding ...

headquartered in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

telegraphed the Central Committee of the KPJ to take all measures to support and alleviate the struggle of the Soviet people, and to organise partisan detachments to fight the Axis in Yugoslavia. The Executive Committee also stressed that the fight, at the current stage, should not be about socialist revolution, but about the liberation from the Axis occupiers. In response to this appeal, the leaders of the KPJ decided on 4 July in Belgrade to launch a nationwide armed uprising, which began three days later in western Serbia. The members of the KPJ-led forces were called Partisans, and their supreme commander was Tito. On 13 July, in Sarajevo, the KPJ Provincial Committee for Bosnia-Herzegovina, headed by Svetozar Vukmanović, organised the province into military regions: Bosanska Krajina, Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

, Tuzla, and Sarajevo.

Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranea ...

. Stojanović's brothers and sisters had lived in Belgrade since before the war.

Yugoslav Partisan

Kozara area

July–August 1941

On the morning of 19 July 1941, Stojanović and Bašić arrived at the camp of the communists and their sympathisers who escaped from Prijedor, situated at Rajlića Kosa above the village of Malo Palančište. The news of Stojanović's escape soon spread throughout the Prijedor district. The group, mostly in the early twenties, enjoyed an increase in their credibility and esteem since a well-known and respected doctor had joined their camp. People from surrounding Serb villages brought food and other supplies to Stojanović and his young comrades. Stojanović gave speeches to the villagers, telling them to be prepared for an impending uprising and urging them to bring him rifles they were hiding in their homes. The camp at Rajlića Kosa was the first Partisan camp in the Kozara area.

Kozara, located in northern Bosanska Krajina and centred around Mount Kozara, covers about . In 1941, the area had a population of nearly 200,000 people. The villagers were mostly Serbs, and the towns in the areathe biggest of which was Prijedorhad a mixed Bosnian Muslim, Serb, and Croat population. Several villages were inhabited by

On the morning of 19 July 1941, Stojanović and Bašić arrived at the camp of the communists and their sympathisers who escaped from Prijedor, situated at Rajlića Kosa above the village of Malo Palančište. The news of Stojanović's escape soon spread throughout the Prijedor district. The group, mostly in the early twenties, enjoyed an increase in their credibility and esteem since a well-known and respected doctor had joined their camp. People from surrounding Serb villages brought food and other supplies to Stojanović and his young comrades. Stojanović gave speeches to the villagers, telling them to be prepared for an impending uprising and urging them to bring him rifles they were hiding in their homes. The camp at Rajlića Kosa was the first Partisan camp in the Kozara area.

Kozara, located in northern Bosanska Krajina and centred around Mount Kozara, covers about . In 1941, the area had a population of nearly 200,000 people. The villagers were mostly Serbs, and the towns in the areathe biggest of which was Prijedorhad a mixed Bosnian Muslim, Serb, and Croat population. Several villages were inhabited by ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

or ''Volksdeutsche''. The economy of Kozara was dominated by agriculture, but there were about 6,000 workers employed in a coal mine and several plants. The first communist cells in the area were established shortly before the Axis invasion, mostly in the towns. Kozara had seen four uprisings against the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

during the 19th century.

On the night of 25 July 1941, at Orlovci, Stojanović and seven other leading communists of Kozara had a meeting with Đuro Pucar

Đurađ "Đuro" Pucar "Stari" ( sr-cyr, Ђурађ Ђуро Пуцар, ; 13 December 1899 – 12 April 1979) was a Yugoslav and Bosnian politician.

During World War II he was a member of the Yugoslav Partisans and was later decorated with the O ...

, the head of the KPJ Regional Committee for Bosanska Krajina. Pucar told the assembled communists that military actions against the enemy should start as soon as possible. The actions should be of a guerrilla type, for which purpose Partisan detachments should be formed. Stojanović and Osman Karabegović

Osman Karabegović (7 September 1911 – 24 June 1996) was a Yugoslav and Bosnian communist politician and a recipient of the Order of the People's Hero. He joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in 1932.

During World War II, he was one of ...

were appointed to lead the uprising in the Prijedor district. Marjanović 1980, pp. 89–93 On 27 July, in western Bosanska Krajina, Partisans took the town of Drvar

Drvar (, ) is a town and municipality located in Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The 2013 census registered the municipality as having a population of 7,036. It is situated in western Bos ...

, marking the beginning of the uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina. At this stage, the insurgents in Kozara were still not organised into military units. In the district of Prijedor, Stojanović and Karabegović had little control over the men from the villages who took up arms. Pucar referred to the district's insurgents as the "Prijedor Company", the bulk of which were villagers, numbering several hundred men. Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, pp. 211–214 Many of them had no firearms.

According to Pucar, the Prijedor Company was directed to attack Ljubija. On 30 July, contrary to Stojanović's direct order, the insurgents attacked Veliko Palančište and rescued fifteen hostages held by the Ustaše. The insurgents then advanced toward Prijedor and developed a position facing the town, which was defended by Croatian Home Guards, Ustaše, and German forces. A front line

A front line (alternatively front-line or frontline) in military terminology is the position(s) closest to the area of conflict of an armed force's personnel and equipment, usually referring to land forces. When a front (an intentional or unin ...

stabilised after three days of fighting, leaving the Prijedor Company in control of seven villages. Railway traffic between Ljubija and Zagreb was disrupted, stopping the export of iron ore from Ljubija to Germany. The uprising in Kozara also involved the districts of Dubica and Novi. By mid-August, five detachments of Partisans had been formed within the territory held by the Kozara insurgents. These detachments, including the Prijedor Detachment commanded by Stojanović, together held the front line facing Kozarac, Prijedor, Lješljani, Dobrljin, Kostajnica, and Dubica. Karasijević 1980, pp. 134–36

The leaders of the uprising in Kozara met on 15 August 1941 in the village of Knežica. At the conference, Stojanović was recognised as the principal leader in Kozara; this recognition mostly resulted from his pre-war social status and good reputation among the people. It was concluded that forming a front line was a mistake because it was not consistent with guerrilla warfare. Marjanović 1980, pp. 94–95 At some point during the conference, Stojanović stressed the importance of keeping as many enemy troops as possible in the area, so that they could not be sent to the Russian front to fight the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. Bašić 1969, pp. 32–35 As the five detachments in the area were tied to their specific territories, it was decided that another detachmentwhich could operate anywhere in Kozarashould be formed. It was decided that Stojanović would command this new Kozara Detachment, and Karabegović would be the political commissar. It was promptly formed with about forty men. Carrying a red banner, the Kozara Detachment paraded for a couple of days through villages in the Partisan-held territory. The villagers gathered and Stojanović delivered speeches.

Croatian Home Guards, Ustaše, and a German battalion from Banja Lukaabout 10,000 soldiersattacked the Partisan-held territory in Kozara on 18 August 1941. The enemy troops broke through the Partisan front line and penetrated into the area. They burnt houses and looted cattle and grain in the villages. Some of the villagers became demoralised, and blamed the Partisans for their losses; some placed white flags on their houses. The Partisan units retreated deeper into forested areas in the mountains. Stojanović led the Kozara Detachment toward Lisina, the highest peak of Kozara. In the evening, he assembled his men and told them that they were in the army of the KPJ and all peoples of Yugoslavia, so they could not allow themselves to be attached to any specific village or area. He advised those who could not detach themselves from their homes to lay down their weapons and leave. Several men left the detachment, which then moved toward Lisina where they organised a camp and spent some time in military training and political indoctrination. The attack of 18 August was the first counter-insurgency operation in Kozara, and the Partisans emerged from it without significant losses.

September–December 1941

The leaders of the Kozara uprising assembled again on 10 September 1941, at the foot of Lisina. The five detachments of the Kozara Partisans were re-arranged into three companies, possessing 217 rifles altogether. At the end of September, the Kozara Partisans began attacking NDH and German troops, initially targeting weaker elements. These operations gave them military experience and they also captured weapons and ammunition from the enemy. More men joined the Partisans, and two more companies had been formed in Kozara by the end of October. The Partisans gained control over a number of villages. Terzić 1957, pp. 136–38 After a reorganization, Partisan units in Kozara were merged into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment in early November 1941. Stojanović was appointed commander of this detachment. By mid-November, it consisted of 670 men organised in six companies and armed with 510 rifles, 5

The leaders of the Kozara uprising assembled again on 10 September 1941, at the foot of Lisina. The five detachments of the Kozara Partisans were re-arranged into three companies, possessing 217 rifles altogether. At the end of September, the Kozara Partisans began attacking NDH and German troops, initially targeting weaker elements. These operations gave them military experience and they also captured weapons and ammunition from the enemy. More men joined the Partisans, and two more companies had been formed in Kozara by the end of October. The Partisans gained control over a number of villages. Terzić 1957, pp. 136–38 After a reorganization, Partisan units in Kozara were merged into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment in early November 1941. Stojanović was appointed commander of this detachment. By mid-November, it consisted of 670 men organised in six companies and armed with 510 rifles, 5 light machine gun

A light machine gun (LMG) is a light-weight machine gun designed to be operated by a single infantryman, with or without an assistant, as an infantry support weapon. LMGs firing cartridges of the same caliber as the other riflemen of the ...

s, and a heavy machine gun

A heavy machine gun (HMG) is significantly larger than light, medium or general-purpose machine guns. HMGs are typically too heavy to be man-portable (carried by one person) and require mounting onto a weapons platform to be operably stable or ...

.