Misnagdic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Misnagdim'' (, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: ''Mitnagdim''; singular ''misnaged''/''mitnaged'') was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries. The ''Misnagdim'' were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where

''Misnagdim'' (, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: ''Mitnagdim''; singular ''misnaged''/''mitnaged'') was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries. The ''Misnagdim'' were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where

Misnagdim

. ''

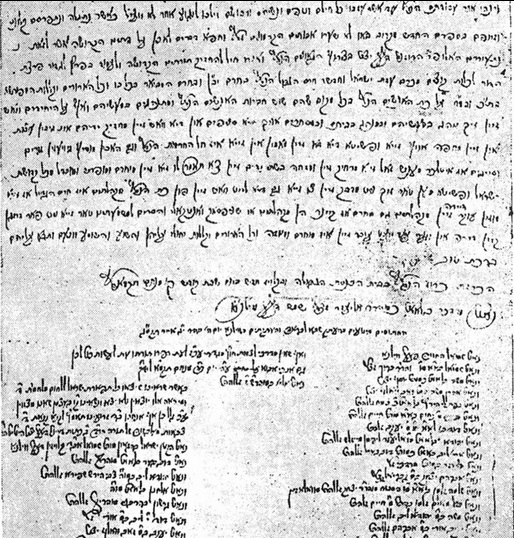

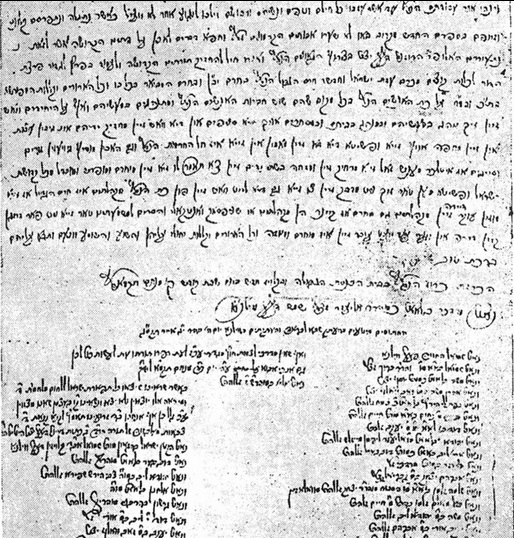

The bans of excommunication against Hasidic Jews in 1772 were accompanied by the public ripping up of several early Hasidic pamphlets. The Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, a prominent rabbi, galvanized opposition to

The bans of excommunication against Hasidic Jews in 1772 were accompanied by the public ripping up of several early Hasidic pamphlets. The Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, a prominent rabbi, galvanized opposition to

''Litvishe'' is a

''Litvishe'' is a

Hasidim And Mitnagdim

(jewishvirtuallibrary.org)

The Vilna Gaon and Leader of the Mitnagdim

(jewishgates.com)

(E. Segal, Univ. Calgary) {{Religious slurs Ashkenazi Jews topics Haredi Judaism in Europe Jewish Lithuanian history Haredi Judaism in Lithuania Jewish groups in Lithuania

''Misnagdim'' (, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: ''Mitnagdim''; singular ''misnaged''/''mitnaged'') was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries. The ''Misnagdim'' were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where

''Misnagdim'' (, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: ''Mitnagdim''; singular ''misnaged''/''mitnaged'') was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries. The ''Misnagdim'' were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

served as the bastion of the movement, but anti-Hasidic activity was undertaken by the establishment in many locales. The most severe clashes between the factions took place in the latter third of the 18th century; the failure to contain Hasidism led the ''Misnagdim'' to develop distinct religious philosophies and communal institutions, which were not merely a perpetuation of the old status quo but often innovative. The most notable results of these efforts, pioneered by Chaim of Volozhin and continued by his disciples, were the modern, independent ''yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are st ...

'' and the Musar movement

The Musar movement (also Mussar movement) is a Jewish ethical, educational and cultural movement that developed in 19th century Lithuania, particularly among Orthodox Lithuanian Jews. The Hebrew term (), is adopted from the Book of Proverbs (1 ...

. Since the late 19th century, tensions with the Hasidim largely subsided, and the heirs of ''Misnagdim'' adopted the epithet Litvishe or Litvaks.

Origins

The rapid spread of Hasidism in the second half of the 18th century greatly troubled many traditionalrabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s; many saw it as heretical. Much of Judaism was still fearful of the messianic movements of the Sabbateans

The Sabbateans (or Sabbatians) were a variety of Jews, Jewish followers, disciples, and believers in Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676),

a Sephardi Jews, Sephardic Jewish rabbi and Kabbalah, Kabbalist who was List of Jewish messiah claimants, proclai ...

and the Frankists, followers of the messianic claimants Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi (; August 1, 1626 – c. September 17, 1676), also spelled Shabbetai Ẓevi, Shabbeṯāy Ṣeḇī, Shabsai Tzvi, Sabbatai Zvi, and ''Sabetay Sevi'' in Turkish, was a Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turk ...

(1626–1676) and Jacob Frank (1726–1791), respectively. Many rabbis suspected Hasidism of an intimate connection with these movements.

Hasidism's founder was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (ca.1700–1760), known as the '' Baal Shem Tov'' ("master of a good name" usually applied to a saintly Jew who was also a wonder-worker), or simply by the acronym

An acronym is a word or name formed from the initial components of a longer name or phrase. Acronyms are usually formed from the initial letters of words, as in ''NATO'' (''North Atlantic Treaty Organization''), but sometimes use syllables, as ...

"Besht" ( he, בעש"ט); he taught that man's relationship with God depended on immediate religious experience, in addition to knowledge and observance of the details of the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

and Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

.

The characteristically ''misnagdic'' approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study; however, it by no means rejected mysticism. The movement's leaders, like the Gaon of Vilna

Gaon may refer to

* Gaon (Hebrew), a non-formal title given to certain Jewish Rabbis

** Geonim, presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies of Sura and Pumbedita

** Vilna Gaon, known as ''the'' Gaon of Vilnius.

* Gaon Music Chart, record chart ...

and Chaim of Volozhin, were deeply immersed in ''kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "receiver"). The defin ...

''. Their difference with the Hasidim was their opposition to involving mystical teachings and considerations in the public life, outside the elitist circles which studied and practiced ''kabbalah''. The Hasidic leaders' inclination to rule in legal matters, binding for the whole community (as opposed to strictures voluntarily adopted by the few), based on mystical considerations, greatly angered the ''Misnagdim''. On another, theoretical level, Chaim of Volozhin and his disciples did not share Hasidism's basic notion that man could grasp the immanence of God's presence in the created universe, thus being able to transcend ordinary reality and potentially infuse common actions with spiritual meaning. However, Volozhin's exact position on the issue is subject to debate among researchers. Some believe that the differences between the two schools of thought were almost semantic, while others regard their understanding of key doctrines as starkly different.

Lithuania became the heartland of the traditionalist opposition to Hasidism, to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "misnaged" became virtually interchangeable terms. In fact, however, a sizable minority of Greater Lithuanian Jews belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch (), is an Orthodox Jewish Hasidic dynasty. Chabad is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, particularly for its outreach activities. It is one of the largest Hasidic grou ...

, Slonim, Karlin-Stolin (Pinsk

Pinsk ( be, Пі́нск; russian: Пи́нск ; Polish: Pińsk; ) is a city located in the Brest Region of Belarus, in the Polesia region, at the confluence of the Pina River and the Pripyat River. The region was known as the Marsh of Pinsk ...

), Amdur and Koidanov.

The first documented opposition to the Hasidic movement was from the Jewish community in Shklow, Belarus in the year 1772. Rabbis and community leaders voiced concerns about the Hasidim because they were making their way to Belarus. The rabbis sent letters forbidding Hasidic prayer houses, urging the burning of Hasidic texts, and humiliating prominent Hasidic leaders. The rabbis imprisoned the Hasidic leaders in an attempt to isolate them from coming into contact with their followers.Nadler, Allan. 2010.Misnagdim

. ''

YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

''The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe'' is a two-volume, English-language reference work on the history and culture of Eastern Europe Jewry in this region, prepared by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and published by Yale Univ ...

''.

Opposition of the Vilna Gaon

Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Judaism, Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory ...

. He believed that the claims of miracles and visions made by Hasidic Jews were lies and delusions. A key point of opposition was that the Vilna Gaon maintained that greatness in Torah and observance must come through natural human efforts at Torah study without relying on any external "miracles" and "wonders". On the other hand, the ''Ba'al Shem Tov'' was more focused on bringing encouragement and raising the morale of the Jewish people, especially following the Chmelnitzki pogroms (1648–1654) and the aftermath of disillusionment in the Jewish masses following the millennial excitement heightened by the failed messianic claims of Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi (; August 1, 1626 – c. September 17, 1676), also spelled Shabbetai Ẓevi, Shabbeṯāy Ṣeḇī, Shabsai Tzvi, Sabbatai Zvi, and ''Sabetay Sevi'' in Turkish, was a Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turk ...

and Jacob Frank. Opponents of Hasidim held that Hasidim viewed their rebbes in an idolatrous fashion.

Hasidism's changes and challenges

Most of the changes made by the Hasidim were the product of the Hasidic approach toKabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "receiver"). The defin ...

, particularly as expressed by Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534–1572), known as "the ARI" and his disciples, particularly Rabbi Chaim Vital

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital ( he, רָבִּי חַיִּים בֶּן יוֹסֵף וִיטָאל; Safed, October 23, 1542 (Julian calendar) and October 11, 1542 (Gregorian Calendar) – Damascus, 23 April 1620) was a rabbi in Safed and the foremo ...

(1543–1620). Both ''Misnagdim ''and hassidim were greatly influenced by the ARI, but the legalistic ''Misnagdim'' feared in Hasidism what they perceived as disturbing parallels to the Sabatean movement. An example of such an idea was the concept that the entire universe is completely nullified to God. Depending on how this idea was preached and interpreted, it could give rise to pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ...

, universally acknowledged as a heresy, or lead to immoral behavior, since elements of Kabbalah can be misconstrued to de-emphasize ritual and to glorify sexual metaphors as a deeper means of grasping some inner hidden notions in the Torah based on the Jews' intimate relationship with God. If God is present in everything, and if divinity is to be grasped in erotic terms, then—''Misnagdim'' feared—Hasidim might feel justified in neglecting legal distinctions between the holy and the profane, and in engaging in inappropriate sexual activities.

The ''Misnagdim'' were seen as using yeshivas

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are stud ...

and scholarship as the center of their Jewish learning, whereas the Hasidim had learning centered around the rebbe tied in with what they considered emotional displays of piety.

The stress of Jewish prayer over Torah study and the Hasidic reinterpretation of ''Torah l'shma'' (Torah study for its own sake), was seen as a rejection of traditional Judaism.

Hasidim did not follow the traditional Ashkenazi prayer rite, and instead used a rite which is a combination of Ashkenazi and Sephardi rites (Nusach Sefard

Nusach Sefard, Nusach Sepharad, or Nusach Sfard is the name for various forms of the Jewish ''siddurim'', designed to reconcile Ashkenazi customs ( he, מנהג "Custom", pl. ''minhagim'') with the kabbalistic customs of Isaac Luria. To this end ...

), based upon Kabbalistic concepts from Rabbi Isaac Luria of Safed. This was seen as a rejection of the traditional Ashkenazi liturgy and, due to the resulting need for separate synagogues

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of wors ...

, a breach of communal unity. In addition they faced criticism for neglecting the halakhic times for prayer.

Hasidic Jews also added some halakhic stringencies on Kashrus

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, yi, כּשר), fro ...

, the laws of keeping kosher. They made certain changes in how livestock were slaughtered and in who was considered a reliable mashgiach

A mashgiach ( he, משגיח, "supervisor"; , ''mashgichim'') or mashgicha (pl. ''mashgichot'') is a Jew who supervises the kashrut status of a kosher establishment. Mashgichim may supervise any type of food service establishment, including sl ...

(supervisor of kashrut). The end result was that they essentially considered some kosher food as less kosher. This was seen as a change of traditional Judaism, and an over stringency of halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

(Jewish law), and, again, a breach of communal unity.

Response to the rise of Hasidism

With the rise of what would become known as Hasidism in the late 18th century, established conservative rabbinic authorities actively worked to stem its growth. Whereas before the breakaway Hasidic synagogues were occasionally opposed but largely checked, its spread into Lithuania andBelarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

prompted a concerted effort by opposing rabbis to halt its spread.

In late 1772, after uniting the scholars of Brisk, Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the admi ...

and other Belorussian and Lithuanian communities, the Vilna Gaon then issued the first of many polemical letters against the nascent Hasidic movement, which was included in the anti-Hasidic anthology, ''Zemir aritsim ve-ḥarvot tsurim'' (1772). The letters published in the anthology included pronouncements of excommunication against Hasidic leaders on the basis of their worship and habits, all of which were seen as unorthodox by the ''Misnagdim''. This included but was not limited to unsanctioned places of worship and ecstatic prayers, as well as charges of smoking, dancing, and the drinking of alcohol. In total, this was seen to be a radical departure from the Misnagdic norm of asceticism, scholarship, and stoic demeanor in worship and general conduct, and was viewed as a development that needed to be suppressed.

Between 1772 and 1791, other Misnagdic tracts of this type would follow, all targeting the Hasidim in an effort to contain and eradicate them from Jewish communities. The harshest of these denouncements came between 1785 and 1815 combined with petitioning of the Russian government to outlaw the Hasidim on the grounds of their being spies, traitors, and subversives.

However, this would not be realized. After the death of the Vilna Gaon in 1797 and the partitions of Poland in 1793 and 1795, the regions of Poland where there were disputes between ''Misnagdim'' and Hasidim came under the control of governments that did not want to take sides in intra-Jewish conflicts, but that wanted instead to abolish Jewish autonomy. In 1804 Hasidism was legalized by the Imperial Russian government, and efforts by the ''Misnagdim'' to contain the now-widespread Hasidim were stymied.

Winding down the battles

By the mid-19th century most of non-Hasidic Judaism had discontinued its struggle with Hasidism and had reconciled itself to the establishment of the latter as a fact. One reason for the reconciliation between the Hasidim and the ''Misnagdim'' was the rise of theHaskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

movement. While many followers of this movement were observant, it was also used by the absolutist state to change Jewish education and culture, which both ''Misnagdim'' and Hasidim perceived as a greater threat to religion than they represented to each other. In the modern era, Misnagdim continue to thrive, but they are more commonly called "Litvishe" or " Yeshivish."

Litvishe

''Litvishe'' is a

''Litvishe'' is a Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

word that refers to Haredi Jews

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

who are not Hasidim (and not Hardalim or Sephardic Haredim). It literally means Lithuanian. While ''Litvishe'' functions as an adjective, the plural noun form often used is ''Litvaks''. The Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

plural noun form which is used with the same meaning is ''Lita'im''. Other expressions areYeshivishe'' and ''Misnagdim''. It has been equated with the term "Yeshiva world".

The words ''Litvishe'', ''Lita'im'', and ''Litvaks'' are all somewhat misleading, because there are also Hasidic Jews from Lithuania, and many Lithuanian Jews who are not Haredim. (The reference to Lithuania does not refer to the country of that name today, but to the historic Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

, which also included all of modern-day Belarus and also most of Ukraine.)

Litvishe Jews largely identify with the ''Misnagdim'', who "objected to what they saw as Hasidic denigration of Torah study and normative Jewish law in favor of undue emphasis on emotionality and religious fellowship as pathways to the Divine." The term ''Misnagdim'' ("opponents") is somewhat outdated since the former opposition between the two groups has lost much of its salience, so the other terms are more common.

See also

*Degel HaTorah

Degel HaTorah ( he, דגל התורה, , Banner of the Torah) is an Ashkenazi Haredi political party in Israel. For much of its existence, it has been allied with Agudat Yisrael, under the name United Torah Judaism.

History

Degel HaTorah ...

* History of the Jews in Lithuania

The history of the Jews in Lithuania spans the period from the 14th century to the present day. There is still a small community in the country, as well as an extensive Lithuanian Jewish diaspora in Israel, the United States and other countrie ...

* Schisms among the Jews

References

External links

Hasidim And Mitnagdim

(jewishvirtuallibrary.org)

The Vilna Gaon and Leader of the Mitnagdim

(jewishgates.com)

(E. Segal, Univ. Calgary) {{Religious slurs Ashkenazi Jews topics Haredi Judaism in Europe Jewish Lithuanian history Haredi Judaism in Lithuania Jewish groups in Lithuania