Military history of New Zealand during World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The military history of New Zealand during World War II began when

The military history of New Zealand during World War II began when

In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and by the war's end a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and overseas. Auxiliary services were raised for women: the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps was the largest, followed by the

In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and by the war's end a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and overseas. Auxiliary services were raised for women: the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps was the largest, followed by the

Over the course of the morning, the 600-strong New Zealand 22 Battalion defending Maleme Airfield found its situation rapidly worsening. The battalion had lost telephone contact with the brigade headquarters; the battalion headquarters (in Pirgos) had lost contact with C and D Companies, stationed on the airstrip and along the Tavronitis-side of Hill 107 (see map) respectively and the battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew ( VC) had no idea of the enemy paratrooper strength to his west, as his

Over the course of the morning, the 600-strong New Zealand 22 Battalion defending Maleme Airfield found its situation rapidly worsening. The battalion had lost telephone contact with the brigade headquarters; the battalion headquarters (in Pirgos) had lost contact with C and D Companies, stationed on the airstrip and along the Tavronitis-side of Hill 107 (see map) respectively and the battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew ( VC) had no idea of the enemy paratrooper strength to his west, as his

While New Zealand soldiers formed the majority of the personnel of the

While New Zealand soldiers formed the majority of the personnel of the  With the Eighth Army now under the new command of Lieutenant-General

With the Eighth Army now under the new command of Lieutenant-General

When

When

On the outbreak of

On the outbreak of

Once trained, the majority of RNZAF aircrew served with ordinary units of the RAF or of the

Once trained, the majority of RNZAF aircrew served with ordinary units of the RAF or of the  The Royal Air Force deliberately set aside certain squadrons for pilots from particular countries. The first of these, 75 Squadron, comprised the Wellingtons and pilots lent by New Zealand in August 1939, which later flew

The Royal Air Force deliberately set aside certain squadrons for pilots from particular countries. The first of these, 75 Squadron, comprised the Wellingtons and pilots lent by New Zealand in August 1939, which later flew

In December 1941, Japan attacked and rapidly conquered much of the area to the north of New Zealand. New Zealand had perforce to look to her own defence as well as help the "mother country". Trainers in New Zealand such as the

In December 1941, Japan attacked and rapidly conquered much of the area to the north of New Zealand. New Zealand had perforce to look to her own defence as well as help the "mother country". Trainers in New Zealand such as the  From mid-1943 at

From mid-1943 at

NZhistory.net.nz - War and society

New Zealand Fighter Pilots Museum

*

New Zealand in the Second World War

The 11th Day: Crete 1941

{{DEFAULTSORT:Military History Of New Zealand During World War Ii New Zealand in World War II Germany–New Zealand relations New Zealand–United Kingdom military relations Germany–United Kingdom military relations

The military history of New Zealand during World War II began when

The military history of New Zealand during World War II began when New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

entered the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

by declaring war on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. New Zealand's forces were soon serving across Europe and beyond, where their reputation was generally very good. In particular, the force of the New Zealanders who stationed in Northern Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

and Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alb ...

was known for its strength and determination, and uniquely so on both sides.

The state of war with Germany was officially held to have existed since 9:30 pm on 3 September 1939 (local time), simultaneous with that of Britain, but in fact New Zealand's declaration of war was not made until confirmation had been received from Britain that their ultimatum to Germany had expired. When Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

broadcast Britain's declaration of war, a group of New Zealand politicians (led by Peter Fraser because Prime Minister Michael Savage

Michael Alan Weiner (born March 31, 1942), known by his professional name Michael Savage, is a far-right author, conspiracy theorist, political commentator, activist, and former radio host. Savage is best known as the host of '' The Savage Na ...

was terminally ill) listened to it on the shortwave radio in Carl Berendsen's room in the Parliament Buildings. Because of static on the radio, they were not certain what Chamberlain had said until a coded telegraph message was received later from London. This message did not arrive until just before midnight because the messenger boy with the telegram in London took shelter due to a (false) air raid warning. The Cabinet acted after hearing the Admiralty's notification to the fleet that war had broken out. The next day the Cabinet approved nearly 30 war regulations as laid down in the War Book, and after completing the formalities with the Executive Council the Governor-General, Lord Galway

Viscount Galway is a title that has been created once in the Peerage of England and thrice in the Peerage of Ireland. The first creation came in the Peerage of England in 1628 in favour of Richard Burke, 4th Earl of Clanricarde. He was made Ear ...

, issued the Proclamation of War, backdated to 9.30 pm on 3 September.

Diplomatically, New Zealand had expressed vocal opposition to fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

in Europe and also to the appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

of fascist dictatorships, and national sentiment for a strong show of force met with general support. Economic and defensive considerations also motivated the New Zealand involvement—reliance on Britain meant that threats to Britain became threats to New Zealand too in terms of economic and defensive ties.

There was also a strong sentimental link between the former British colony and the United Kingdom, with many seeing Britain as the "mother country" or "Home". This was reinforced by New Zealand's status as a " white dominion" of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. The New Zealand Prime Minister

The prime minister of New Zealand ( mi, Te pirimia o Aotearoa) is the head of government of New Zealand. The prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, leader of the New Zealand Labour Party, took office on 26 October 2017.

The prime minister (inf ...

of the time Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Savage was born in the Colon ...

summed this up at the outbreak of war with a broadcast on 5 September (largely written by the Solicitor-General Henry Cornish

Henry Cornish (died 1685) was a London alderman, executed in the reign of James II of England.

Life

He was a well-to-do merchant of London, and alderman of the ward of St Michael Bassishaw; in the ''London Directory'' for 1677 he is described as ...

) that became a popular cry in New Zealand during the war:

It is with gratitude in the past, and with confidence in the future, that we range ourselves without fear beside Britain, where she goes, we go! Where she stands, we stand!New Zealand provided personnel for service in the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) and in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

and was prepared to have New Zealanders serving under British command. There were, however, many instances of New Zealanders commanding troops on their own, whether their own or a mixture of theirs and foreign ones; notable commanders include Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg

Lieutenant-General Bernard Cyril Freyberg, 1st Baron Freyberg, (21 March 1889 – 4 July 1963) was a British-born New Zealand soldier and Victoria Cross recipient, who served as the 7th Governor-General of New Zealand from 1946 to 1952.

Frey ...

and Lieutenant-Colonel Fred Baker. Their stationing in North Africa and Greece, specifically during the First and Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ea ...

Battles of El Alamein and the Freyburg-commanded Crete campaign, was generally well known on either side for its strength, effectiveness and "spiritual" connection. Royal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeal ...

(RNZAF) pilots, many trained in the Empire Air Training Scheme

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), or Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a massive, joint military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zea ...

, were sent to Europe but, unlike the other Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s, New Zealand did not insist on its aircrews serving with RNZAF squadrons, so speeding up the rate at which they entered service. The Long Range Desert Group

The Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) was a reconnaissance and raiding unit of the British Army during the Second World War.

Originally called the Long Range Patrol (LRP), the unit was founded in Egypt in June 1940 by Major Ralph Alger Bagnold, acti ...

was formed in North Africa in 1940 with New Zealand and Rhodesian as well as British volunteers, but included no Australians for the same reason.

The New Zealand government

, background_color = #012169

, image = New Zealand Government wordmark.svg

, image_size=250px

, date_established =

, country = New Zealand

, leader_title = Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

, appointed = Governor-General

, main_organ =

...

placed the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy

The New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy also known as the New Zealand Station was formed in 1921 and remained in existence until 1941. It was the precursor to the Royal New Zealand Navy. Originally, the Royal Navy was solely responsible for ...

at the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

's disposal and made available to the RAF 30 new Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

medium bombers waiting in the United Kingdom for shipping to New Zealand. The New Zealand Army

, image = New Zealand Army Logo.png

, image_size = 175px

, caption =

, start_date =

, country =

, branch = ...

contributed the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

(2NZEF).

Home front

In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and by the war's end a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and overseas. Auxiliary services were raised for women: the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps was the largest, followed by the

In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and by the war's end a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and overseas. Auxiliary services were raised for women: the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps was the largest, followed by the Women's Auxiliary Air Force

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose members were referred to as WAAFs (), was the female auxiliary of the Royal Air Force during World War II. Established in 1939, WAAF numbers exceeded 180,000 at its peak strength in 1943, with over 2 ...

, and then the Women's Royal New Zealand Naval Service.

Conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

was introduced in June 1940, and volunteering for Army service ceased from 22 July 1940, although entry to the Air Force and Navy remained voluntary. Difficulties in filling the Second and Third Echelons for overseas service in 1939–1940, the Allied disasters of May 1940 and public demand led to its introduction. Four members of the cabinet including Prime Minister Peter Fraser had been imprisoned for anti-conscription activities in World War I, the Labour Party was traditionally opposed to it, and some members still demanded ''conscription of wealth before men''. From January 1942, workers could be ''manpowered'' or directed to essential industries.

Access to imports was hampered and rationing made doing some things very difficult. Fuel and rubber shortages were overcome with novel approaches. In New Zealand, industry switched from civilian needs to making war materials on a much larger scale than is commonly understood today. New Zealand and Australia supplied the bulk of foodstuffs to American forces in the South Pacific, as Reverse Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

. With earlier commitments to supply food to Britain this led to both Britain and America (MacArthur) complaining about food going to the other ally (and Britain commenting on the much more generous ration allocations for American soldiers; General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

admitted that the meat ration was too large, but he was not going to challenge the ration set by Congress). By 1943 there was a manpower crisis, and eventually the withdrawal of the Third Division from the Pacific. To alleviate manpower shortages in the agricultural sector, the New Zealand Women's Land Army was created in 1940; a total of 2,711 women served on farms throughout New Zealand during the war.

During the winter of 1944 the government hastened work on docks and repair facilities at Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

and Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

following a British request, to supplement the bases and repair yards in Australia needed for the British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships o ...

.

Land forces

Greek campaign

The New Zealand authorities deployed the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force for combat in three echelons – all originally destined forEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, but one diverted to Scotland (it would arrive there in June 1940) following the German invasion of France. In April 1941, after a period training in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, 2NZEF's New Zealand 2nd Division, stationed in Egypt, deployed to take part in the defence of Greece against invasion by Italian troops, and soon German forces too when they joined the invasion. This defence was mounted alongside British and Australian units – the corps-size Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

contingent under the command of British General Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during the ...

known together as W Force, supported a weakened Greek Army.

As German panzers began a swift advance into Greece on 6 April, the British and Commonwealth troops found themselves being outflanked and were forced into retreat. By 9 April, Greece had been forced to surrender and the 40,000 W Force troops began a withdrawal from the country to Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Egypt, the last New Zealand troops leaving by 29 April.

During this brief campaign, the New Zealanders lost 261 men killed, 1,856 captured and 387 wounded.

Crete

Two of the three brigades of the New Zealand 2nd Division had evacuated to Crete from Greece (the third and division headquarters went toAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

). New Zealanders bolstered the Crete garrison to a total of 34,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers (25,000 evacuated from Greece) alongside 9,000 Greek troops (see Crete order of battle for more detail). Evacuated to Crete on 28 April (having disregarded an order to leave on 23 April), the New Zealand General Freyberg became commander of the Allied forces on Crete on the 30th. Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley P ...

intercepts of German signals had already alerted Allied commanders to the German plans to invade Crete with ''Fallschirmjäger

The ''Fallschirmjäger'' () were the paratrooper branch of the German Luftwaffe before and during World War II. They were the first German paratroopers to be committed in large-scale airborne operations. Throughout World War II, the commander ...

'' (Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

paratroopers). With this knowledge, General Freyberg began to prepare the island's defences, hampered by a lack of modern and heavy equipment, as the troops from Greece had in most cases had to leave only with their personal weapons. Although German plans had underestimated Greek, British and Commonwealth numbers, and incorrectly presumed that the Cretan population would welcome the invasion, Freyberg was still faced with the harsh prospect that even lightly equipped paratroopers could overwhelm the island's defences.

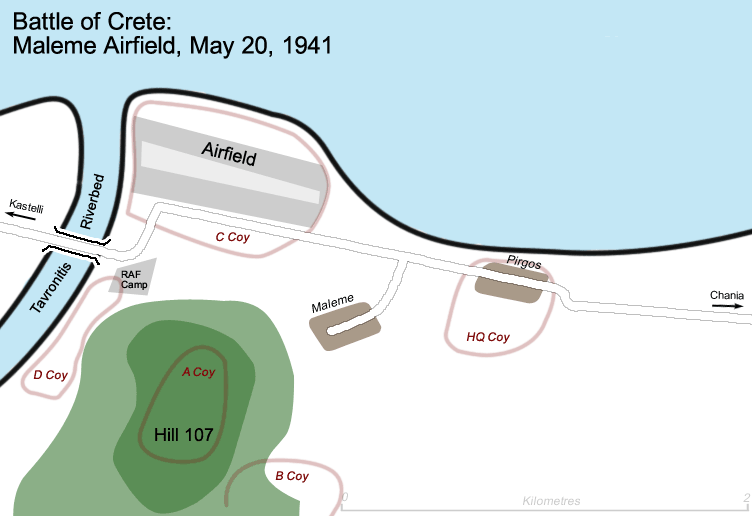

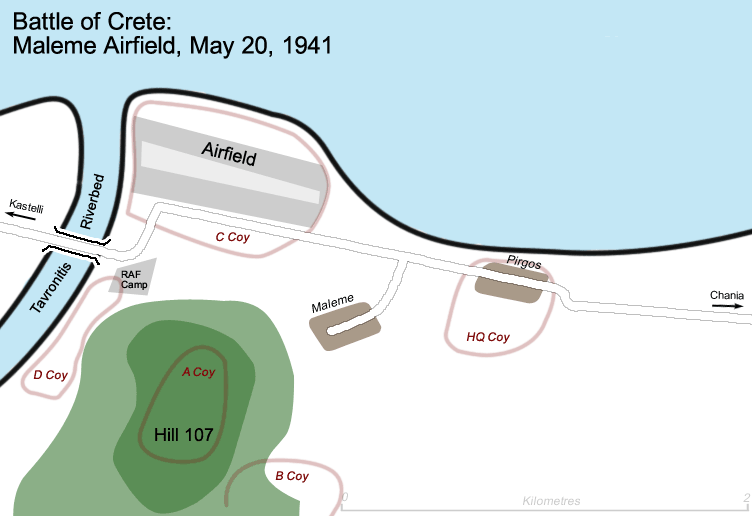

Operation Mercury opened on 20 May when the German Luftwaffe delivered ''Fallschirmjäger'' around the airfield at Maleme and the Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

area, at around 8:15 pm, by paradrop and gliders. Most of the New Zealand forces were deployed around this north-western part of the island and with British and Greek troops they inflicted heavy casualties upon the initial German attacks. Despite near complete defeat for their landing troops east of the airfield and in the Galatas region, the Germans were able to gain a foothold by mid-morning west of Maleme Airfield (5 Brigade's area) – along the Tavronitis riverbed and in the Ayia Valley to the east (10 Brigade's area – dubbed 'Prison Valley').

Maleme

Over the course of the morning, the 600-strong New Zealand 22 Battalion defending Maleme Airfield found its situation rapidly worsening. The battalion had lost telephone contact with the brigade headquarters; the battalion headquarters (in Pirgos) had lost contact with C and D Companies, stationed on the airstrip and along the Tavronitis-side of Hill 107 (see map) respectively and the battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew ( VC) had no idea of the enemy paratrooper strength to his west, as his

Over the course of the morning, the 600-strong New Zealand 22 Battalion defending Maleme Airfield found its situation rapidly worsening. The battalion had lost telephone contact with the brigade headquarters; the battalion headquarters (in Pirgos) had lost contact with C and D Companies, stationed on the airstrip and along the Tavronitis-side of Hill 107 (see map) respectively and the battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew ( VC) had no idea of the enemy paratrooper strength to his west, as his observation post

An observation post (commonly abbreviated OP), temporary or fixed, is a position from which soldiers can watch enemy movements, to warn of approaching soldiers (such as in trench warfare), or to direct fire. In strict military terminology, an ...

s lacked wireless sets. While a platoon of C Company situated northwest of the airfield, nearest the sea, was able to repel German attacks along the beach, attacks across the Tavronitis bridge by ''Fallschirmjäger'' were able to overwhelm weaker positions and take the Royal Air Force camp. Not knowing whether C and D Companies had been overrun, and with German mortars firing from the riverbed, Colonel Andrew (with unreliable wireless contact) ordered the firing of white and green signals – the designated emergency signal for 23 Battalion (to the south-east of Pirgos), under the command of Colonel Leckie, to counterattack. The signal was not spotted, and further attempts were made to get the message through to no avail. At 5:00 pm, contact was made with Brigadier James Hargest at the New Zealand 2nd Division headquarters, but Hargest responded that 23 Battalion was fighting paratroopers in its own area, an untrue and unverified assertion.

Faced with a seemingly desperate situation, Colonel Andrew played his trump card – two Matilda tanks, which he ordered to counterattack with the reserve infantry platoon and some additional gunners turned infantrymen. The counterattack failed – one tank had to turn back after suffering technical problems (the turret would not traverse properly) and the second ignored the German positions in the RAF camp and the edge of the airfield, heading straight for the riverbed. This lone tank stranded itself quickly on a boulder, and faced with the same technical difficulties as the first Matilda, the crew abandoned the vehicle. The exposed infantry were repelled by the ''Fallschirmjäger''. At around 6:00 pm, the failure was reported to Brigadier Hargest and the prospect of a withdrawal was raised. Colonel Andrew was informed that he could withdraw if he wished, with the famous reply "Well, if you must, you must," but that two companies (A Company, 23 Battalion and B Company, 28 (Māori) Battalion) were being sent to reinforce 22 Battalion. To Colonel Andrew, the situation seemed bleak; ammunition was running low, the promised reinforcements seemed not to be forthcoming (one got lost, the other simply did not arrive as quickly as expected) and he still had no idea how C and D companies were. The two companies in question were in fact resisting strongly on the airfield and above the Tavronitis riverbed and had inflicted far greater losses on the Germans than they had suffered. At 9:00 pm, Andrew made the decision to make a limited withdrawal, and once that had been carried out, a full one to the 21 and 23 Battalion positions to the east. By midnight, all of 22 Battalion had left the Maleme area, with the exception of C and D Companies which withdrew in the early morning of the 21st upon discovering that the rest of the battalion had gone.

This allowed German troops to seize the airfield proper without opposition and take nearby positions to reinforce their hold on it. Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German aero ...

transport aircraft flew in ammunition and supplies, as well as the rest of the ''Fallschirmjäger'' and troops of the 5th Mountain Division. Although the landings were extremely hazardous, with the airstrip under direct British artillery fire, substantial reinforcement was made. On 21 May, the village of Maleme was attacked and captured by the Germans, and a counterattack was made by the 20 Battalion (with reinforcements from the Australian 2/7 Battalion), 28 (Māori) Battalion and later 21 Battalion. The attack was hampered by communications problems and although the New Zealanders made significant advances in some areas, the overall picture was one of stiff German resistance. 5 Brigade fell back to a new line at Platanias

Platanias (Greek: Πλατανιάς) is a village and municipality on the Greek island of Crete. It is located about west from the city of Chania and east of Kissamos, on Chania Bay. The seat of the municipality is the village Gerani. Platani ...

, leaving Maleme securely in German hands, allowing them to freely build up their force in this region.

Galatas

On the night of 23 May and the morning of 24 May, 5 Brigade withdrew again to the area near Daratsos, forming a new front line running from Galatas to the sea. The relatively fresh 18 Battalion replaced the worn troops from Maleme and Platanias, deploying 400 men on a two kilometre front. Galatas had come under attack on the first day of the battle — ''Fallschirmjäger'' and gliders had landed around Chania and Galatas, to suffer extremely heavy casualties. They retreated to "Prison Valley," where they rallied around Ayia Prison and repulsed a confused counterattack by two companies of 19 Battalion and three light tanks. Pink Hill (so named for the colour of its soil), a crucial point on the Galatas heights, was attacked several times by the Germans that day, and was remarkably held by the Division Petrol Company, with the aid of Greek soldiers, though at a heavy cost to both sides. The Petrol Company comprised poorly armed support troops, primarily drivers and technicians, and by the day's end all their officers and most of their non-commissioned officers had been wounded. They withdrew around dusk. On the second day, the New Zealanders attacked nearby Cemetery Hill to take pressure off their line, and although they had to withdraw, for it was too exposed, the hill became ano man's land

No man's land is waste or unowned land or an uninhabited or desolate area that may be under dispute between parties who leave it unoccupied out of fear or uncertainty. The term was originally used to define a contested territory or a dump ...

as Pink Hill was, relieving the New Zealand front. Day three, 22 May, saw German soldiers take Pink Hill. The Petrol Company and some infantry reserve prepared a counterattack, but a notable incident pre-empted them – as told by Driver A. Pope:

Out of the trees came aptainForrester of the Buffs, clad in shorts, a long yellow army jersey reaching down almost to the bottom of the shorts, brass polished and gleaming, web belt in place and waving his revolver in his right hand ..It was a most inspiring sight. Forrester was at the head of a crowd of disorderly Greeks, including women; one Greek had a shot gun with a serrated-edge bread knife tied on like a bayonet, others had ancient weapons—all sorts. Without hesitation this uncouth group, with Forrester right out in front, went over the top of a parapet and headlong at the crest of the hill. The ermansfled.Days four and five featured only skirmishes between the two forces. Luftwaffe air raids targeted Galatas on 25 May at 8:00 am, 12:45 pm and 1:15 pm, and the German ground attack came at around 2:00 pm. 100 Mountain and 3 Parachute Regiment attacked Galatas and the high ground around it, while two battalions of 85 Mountain Regiment attacked eastwards, with the aim of cutting Chania off. The New Zealand defenders, though prepared, suffered from a disadvantage: 18 Battalion, 400 men, was the only fresh infantry formation on the line – the rest were non-infantry groups like the Petrol Company and the Composite Battalion, consisting of mechanical, supply and artillery troops. The fighting was fierce, especially along the north of the line, and platoons and companies were forced to retreat. Brigadier Lindsay Inglis called for reinforcement and received 23 Battalion, which, along with an improvised group of reinforcements scraped together at Brigade headquarters (including the brigade band and the Kiwi Concert Party), stabilised the north of the line. South of Galatas, only 18 Battalion and the Petrol Company were defending – 18 Battalion was forced to withdraw, and the Petrol Company on Pink Hill followed suit after eventually becoming aware of this. 19 Battalion was the only formation still in combat on Pink Hill, and they too withdrew. These forces withdrew past Galatas, as no defenders were in the village to link up with. By nightfall, German troops had occupied Galatas, and Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Kippenberger prepared a counterattack. Two tanks led two companies of 23 Battalion into Galatas at a running pace – heavy fire was encountered and as the tanks went ahead towards the town square, the infantry cleared each house of German soldiers as they worked inward. When the infantry caught up with the tanks, they found one out of action. With German fire coming primarily from one side of the square, a bayonet charge was mounted and the New Zealanders cleared the German opposition. Patrols quelled resistance elsewhere in Galatas – apart from one small strongpoint, Galatas was back in New Zealand hands. A conference between Brigadier Inglis and his commanders reached the consensus that Allied forces needed to make a further counterattack urgently – and that without a counterattack Crete would fall to the Germans. Despite hard fighting so far in the battle, the 28 (Māori) Battalion was considered to be the only "fresh" battalion available and the only one capable of carrying out such an attack. Their commander was willing to mount the attack despite the difficulty, but a representative sent from Brigadier Edward Puttick at New Zealand 2nd Division headquarters recommended against such an attack for fear of being unable to hold the line subsequently. The counter-attack was scrapped, and so too was Galatas, its position being far too vulnerable to hold. However, without Galatas the whole line was untenable and so the New Zealanders again retreated, forming a line from the coast to Perivolia and Mournies, near the Australian 19th Brigade.

North Africa

While New Zealand soldiers formed the majority of the personnel of the

While New Zealand soldiers formed the majority of the personnel of the Long Range Desert Group

The Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) was a reconnaissance and raiding unit of the British Army during the Second World War.

Originally called the Long Range Patrol (LRP), the unit was founded in Egypt in June 1940 by Major Ralph Alger Bagnold, acti ...

when it was formed in 1940, and a small number of New Zealand transport and signals units supported Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also it, Battaglia della Marmarica) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British, Empire and Commonwealth forces attacked Italian forces of ...

in the Western Desert in December 1940, it was not until November 1941 that the 2nd New Zealand Division

The 2nd New Zealand Division, initially the New Zealand Division, was an infantry division of the New Zealand Military Forces (New Zealand's army) during the Second World War. The division was commanded for most of its existence by Lieutenant ...

became fully involved in the North African Campaign. Following its evacuation from Crete, the division regrouped at its camp near Maadi

Maadi ( ar, المعادي / transliterated: ) is a leafy suburban district south of Cairo, Egypt, on the east bank of the Nile about upriver from downtown Cairo. The Nile at Maadi is parallelled by the Corniche, a waterfront promenade a ...

, at the base of the desert slopes of Wadi Digla and Tel al-Maadi. Reinforcements arrived from New Zealand to bring the division back up to strength and the training, cut short by the deployment to Greece and Crete, was completed.

On 18 November 1941, Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December 1941) was a military operation of the Western Desert Campaign during the Second World War by the British Eighth Army (with Commonwealth, Indian and Allied contingents) against the Axis forces (Ge ...

was launched to lift the Siege of Tobruk

The siege of Tobruk lasted for 241 days in 1941, after Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) of the Second World ...

(the third such attack), under the command of Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Alan Cunningham

General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign during the Second World War. Later he served as the seventh ...

and the 2nd New Zealand Division (integrated into the British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Force ...

) took part in the offensive, crossing the Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

n frontier into Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

. Operation Crusader was an overall success for the British, although Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

inflicted heavy armour and infantry losses before its weakened and under-supplied units retreated to El Agheila

El Agheila ( ar, العقيلة, translit=al-ʿUqayla ) is a coastal city at the southern end of the Gulf of Sidra in far western Cyrenaica, Libya. In 1988 it was placed in Ajdabiya District; it was in that district until 1995. It was removed from ...

and halted the British advance. The New Zealand troops were the ones to relieve Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near ...

after fighting around Sidi Rezegh

''Sidi'' or ''Sayidi'', also Sayyidi and Sayeedi, ( ar, سيدي, Sayyīdī, Sīdī (dialectal) "milord") is an Arabic masculine title of respect. ''Sidi'' is used often to mean "saint" or "my master" in Maghrebi Arabic and Egyptian Arabic. W ...

, where Axis tanks had inflicted heavy casualties against the several New Zealand infantry battalions, protected by very little of their own armour. In February 1942, with Crusader completed, the New Zealand government

, background_color = #012169

, image = New Zealand Government wordmark.svg

, image_size=250px

, date_established =

, country = New Zealand

, leader_title = Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

, appointed = Governor-General

, main_organ =

...

insisted that the division be withdrawn to Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to recover – 879 men were killed and 1,700 wounded during the operation, the most costly battle the 2nd New Zealand Division fought in the Second World War.

On 14 June 1942, the generals recalled the New Zealanders from their occupation duties in Syria, as the Afrika Korps had broken through Gazala and captured Tobruk. The New Zealanders, put on the defence, found themselves encircled at Minqar Qa'im, but escaped thanks to brutally efficient hand-to-hand fighting by 4 Brigade. The British forces prevented Rommel's advance from reaching Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

and the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

in the First Battle of El Alamein

The First Battle of El Alamein (1–27 July 1942) was a battle of the Western Desert campaign of the Second World War, fought in Egypt between Axis (German and Italian) forces of the Panzer Army Africa—which included the under Field Marsha ...

, where New Zealand troops captured Ruweisat Ridge

Ruweisat Ridge is a geographical feature in the Western Egyptian desert, midway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Qattara Depression. During World War II was a prominent part of the defence line in the First and Second Battle of El Alamein

...

in a successful night attack. However, they were unable to bring their anti-tank weapons forward, and more importantly, British armour did not move forward to support the soldiers. Heavy casualties were suffered by the two New Zealand brigades involved, as they were attacking by German tanks, and several thousand men were taken prisoner. Charles Upham

Charles Hazlitt Upham, (21 September 1908 – 22 November 1994) was a New Zealand soldier who was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) twice during the Second World War - for gallantry in Crete in May 1941, and in Egypt, in July 1942. He was the ...

earned a bar for his Victoria Cross in this battle.

With the Eighth Army now under the new command of Lieutenant-General

With the Eighth Army now under the new command of Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence an ...

, the Army launched a new offensive on 23 October against the stalled Axis forces in the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa had prevented th ...

. On the first night, as part of Operation Lightfoot, the New Zealand 2nd Division, with British divisions, moved through the deep Axis minefields while engineers cleared routes for British tanks to follow. The New Zealanders successfully captured their objectives on Miteiriya Ridge. By 2 November, with the attack bogged down, Montgomery launched a new initiative to the south of the battle lines, Operation Supercharge, with the ultimate goal of destroying the Axis army. The experienced 2nd New Zealand Division was called on to carry out the initial thrust – the same sort of attack they had made in ''Lightfoot''. As the under-strength division could not achieve this mission alone, two British brigades were attached. The German line was breached by British armour and, on 4 November, the Afrika Korps, faced with the prospect of complete defeat, skillfully withdrew.

The New Zealanders continued to advance with the Eighth Army through the Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

, driving the Afrika Korps back into Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, and notably fought at Medenine

Medenine ( ar, مدنين ) is the major town in south-eastern Tunisia, south of the port of Gabès and the Island of Djerba, on the main route to Libya. It is the capital of Medenine Governorate.

Overview

In pre-colonial times, Medenine wa ...

, the Tebaga Gap

The Tebaga Gap of southern Tunisia is a low mountain pass located in rough rocky broken country giving entry to the inhabited coastal plain to the north and east from much less hospitable desert dominated terrain in southern and south-western Tun ...

and Enfidaville

Enfidha (or Dar-el-Bey, ar, دار البي ') is a town in north-eastern Tunisia with a population of approximately 10,000. It is visited by tourists on their way to Takrouna. Enfidha is located at around . It lies on the railway between Tunis ...

. On 13 May 1943, the North African campaign ended with the surrender of the last 275,000 Axis troops in Tunisia. On 15 May, the division began a withdrawal back to Egypt and, by 1 June, the division had returned to Maadi and Helwan

Helwan ( ar, حلوان ', , cop, ϩⲁⲗⲟⲩⲁⲛ, Halouan) is a city in Egypt and part of Greater Cairo, on the bank of the Nile, opposite the ruins of Memphis. Originally a southern suburb of Cairo, it served as the capital of the now d ...

, on standby for use in Europe. Total losses for the 2nd New Zealand Division since November 1941 stood at 2,989 killed, 7,000 wounded and 4,041 taken prisoner.

Italy

During October and November 1943, New Zealand troops from the 2nd New Zealand Division assembled inBari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

in Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

, weeks after the Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allied amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign of World War II. The operation was undertaken by General Sir Harold Alexander's 15th Army ...

. In November, the division crossed the Sangro River

The Sangro is a river in eastern central Italy, known in ancient times as Sagrus from the Greek ''Sagros'' or ''Isagros'', ''Ισαγρος''.

It rises in the middle of Abruzzo National Park near Pescasseroli in the Apennine Mountains. It flows s ...

with a view to breaching the German Gustav Line

The Winter Line was a series of German and Italian military fortifications in Italy, constructed during World War II by Organisation Todt and commanded by Albert Kesselring. The series of three lines was designed to defend a western section ...

and advancing to Rome, capturing the village of Castelfrentano in the Abruzzo

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1 ...

(part of the Gustav Line) on 2 December. The division attacked Orsogna on the next day, but was repulsed by the strong German defence. In January 1944, the 2nd New Zealand was withdrawn from the stalled front line and transferred to the Cassino

Cassino () is a ''comune'' in the province of Frosinone, Southern Italy, at the southern end of the region of Lazio, the last city of the Latin Valley.

Cassino is located at the foot of Monte Cairo near the confluence of the Gari and Liri ri ...

sector, where other Allied troops were bogged down in costly fighting for the position of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first ho ...

. On 17 February, the division attacked Cassino

Cassino () is a ''comune'' in the province of Frosinone, Southern Italy, at the southern end of the region of Lazio, the last city of the Latin Valley.

Cassino is located at the foot of Monte Cairo near the confluence of the Gari and Liri ri ...

but it was strongly defended and they withdrew in early April. Cassino was eventually captured on 18 May by British and Polish troops, with the support of New Zealand artillery units. On 16 July, the division captured Arezzo

Arezzo ( , , ) , also ; ett, 𐌀𐌓𐌉𐌕𐌉𐌌, Aritim. is a city and '' comune'' in Italy and the capital of the province of the same name located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about southeast of Florence at an elevation of above sea lev ...

and reached Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

on 4 August. By the end of October they had reached the Savio River, and Faenza was captured on 14 December. In Operation Grapeshot

The spring 1945 offensive in Italy, codenamed Operation Grapeshot, was the final Allied attack during the Italian Campaign in the final stages of the Second World War. The attack into the Lombard Plain by the 15th Allied Army Group started on ...

, the final Allied offensive in Italy, the division crossed the Senio River on 8 April 1945, then began their final push across the Santerno and Gaiana Rivers, finally crossing the Po River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira, a right bank tributary, is included. T ...

on Anzac Day

, image = Dawn service gnangarra 03.jpg

, caption = Anzac Day Dawn Service at Kings Park, Western Australia, 25 April 2009, 94th anniversary.

, observedby = Australia Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Cook Islands Ne ...

1945. The division captured Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

on 28 April 1945, crossed the Isonzo River on 1 May, and reached Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into pr ...

on 2 May, the day of the German unconditional surrender.

Campaigns in the Pacific

When

When Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

entered the war in December 1941, the New Zealand Government raised another expeditionary force, known as the 2nd N.Z.E.F. In the Pacific, or 2nd N.Z.E.F. (I.P.), for service with the Allied Pacific Ocean Areas command. This force supplemented existing garrison troops in the South Pacific. The main fighting formation of the 2nd N.Z.E.F. (I.P.) comprised the New Zealand 3rd Division

The 3rd New Zealand Division was a division of the New Zealand Military Forces. Formed in 1942, it saw action against the Japanese in the Pacific Ocean Areas during the Second World War. The division saw action in the Solomon Islands campaign durin ...

. However, the 3rd Division never fought as a complete formation; its component brigades became involved in semi-independent actions as part of the Allied forces in the Solomons at Vella Lavella), Treasury Islands and Green Island. The War Cabinet had held the division at two rather than three brigades, and this limited its use, although MacArthur had a role for a full division; Halsey was "greatly disappointed that New Zealand could not furnish a division with three full brigades" but his deputy accepted that the division was last in New Zealand's Pacific priorities, after the air force, navy and food production. Preference was given to the Second Division, on the advice of Churchill and Roosevelt. However New Zealand also had 19,000 troops in New Caledonia, Tonga, Norfolk Island and Fiji in 1943; and the 3,000 Air Force personnel would rise to 6,000 when more planes were available. In Australia the reaction of Curtin (but not Evatt) to the withdrawal of the Third Division was hostile.

Eventually, American formations replaced the New Zealand army units in the Pacific, which released personnel for service with the 2nd Division in Italy, or to cover shortages in the civilian labour-force. New Zealand Air Force squadrons and Navy units continued to contribute to the Allied island-hopping campaign, with several RNZAF squadrons supporting Australian ground troops on Bougainville.

German and Japanese surface raiders and submarines operated in New Zealand waters on several occasions in 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943 and 1945, sinking a total of four ships while Japanese reconnaissance aircraft flew over Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

and Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

preparing for a projected Japanese invasion of New Zealand.

In 1945 Peter Fraser wanted to contribute to a Commonwealth force against Japan, including an army contribution of at least two brigade groups as "from previous experience small units are given the harder jobs or are not properly supported". But during the Hamilton by-election, 1945, National had campaigned on withdrawing New Zealand troops from Italy and restricting New Zealand's role in the Pacific War to food supply, though Labour wanted to keep New Zealand troops in the Pacific to "have a say" in the peace. So Fraser met the Opposition leaders Sidney Holland

Sir Sidney George Holland (18 October 1893 – 5 August 1961) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 25th prime minister of New Zealand from 13 December 1949 to 20 September 1957. He was instrumental in the creation and consolidation o ...

and Adam Hamilton before the Dunedin North by-election, 1945, noting the divisions in his own caucus. Holland agreed with Fraser not to refer to the matter (which was agitating the whole country) during the by-election campaign, saying it would not be right to divide the House on this. In a (non-broadcast) semi-secret section on 2 August the House agreed to participate in a force against Japan "within the capacity of our remaining resources of manpower". And National's proposal to reduce the total armed forces to 55,000 was accepted.

The Commonwealth Corps

The Commonwealth Corps was the name given to a proposed British Commonwealth army formation, which was scheduled to take part in the planned Allied invasion of Japan during 1945 and 1946. The corps was never formed, however, as the Japanese surr ...

, planned to participate in Operation Downfall

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ...

, the Allied invasion of Japan, would have included New Zealand Army and Air Force units, with Air Force units included in Tiger Force

Tiger Force was the name of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought in the Vietnam War from November 1965 to November 1967. The unit ...

to bomb Japan.

In 1945, some troops who had recently returned from Europe with the 2nd Division, got drafted to form a contribution (known as J-Force) toward the British Commonwealth Occupation Force

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was the British Commonwealth taskforce consisting of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand military forces in occupied Japan, from 1946 until the end of occupation in 1952.

At its peak, ...

(BCOF) in southern Japan. No. 14 Squadron RNZAF, equipped with Corsair fighters, and RNZN ships also joined BCOF.

Naval actions

At the outbreak of war in 1939, New Zealand still contributed to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy. Many New Zealanders served alongside other Commonwealth sailors in vessels of the Royal Navy and would continue to do so throughout the war. took part in theBattle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

(13 December 1939) as part of a small British force against the German pocket battleship . The action resulted in the German ship retiring to neutral Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

and its scuttling a few days later.

Another cruiser, , destroyed the Italian auxiliary cruiser off the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

on 27 February 1941. The New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy became the Royal New Zealand Navy when King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

granted it the name on 1 October 1941.

Naval war against Japan

On 13 December 1939, New Zealand deployed its naval forces against Germany. The first vessel into action against Japan, the minesweeper , steamed forward toFiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

, arriving on Christmas Day, 1941. HMNZS ''Rata'' and ''Muritai'' arrived in January 1942, followed by the corvettes , and , to form a minesweeping flotilla.

The ''Achilles'', ''Leander'', and initially served as troop-convoy escorts in the Pacific in early 1942. In January 1942, ''Monowai'' inconclusively engaged a Japanese submarine off Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

. On 4 January 1943, a Japanese bomber destroyed the aft gun-house of ''Achilles'' off Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

. In January 1943, a morale-boosting episode occurred: the duel ''Kiwi'' and ''Moa'' fought with the much larger . Unable to pierce the ''I-1'', the ''Kiwi'' rammed her three times, destroying her ability to dive. ''Moa'' then hounded ''I-1'' onto a reef, where she broke up. In April 1943, an aerial attack sunk the ''Moa'' in Tulagi

Tulagi, less commonly known as Tulaghi, is a small island——in Solomon Islands, just off the south coast of Ngella Sule. The town of the same name on the island (pop. 1,750) was the capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate from 1 ...

Harbour in the Solomons. The ''Tui'' participated in the sinking of the 2,200-ton before joining the ''Kiwi'' in redeploying to New Guinea, while the corvette went to the Ellice Islands.

The ''Leander'' helped sink the in the Battle of Kolombangara on the night of 11–12 July 1943. Holed by a Japanese torpedo during the engagement, the ''Leander'' withdrew to Auckland for repairs. Twelve New Zealand built Fairmile launches of the 80th and 81st Motor Launch Flotillas went forward in early 1944.

The cruiser bombarded Sabang (in Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

) in July 1944, and with the recommissioned ''Achilles'' joined the British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships o ...

, later re-inforced by the corvette . The Fleet detached ''Achilles'' to tow the damaged destroyer ''Ulster'' to the New Zealand Hospital Ship ''Maunganui'' in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

(where the was at that time stationed). Both ''Gambia'' and ''Achilles'' bombarded Japanese positions in the Sakishima Group in May 1945. They were supported by 100 New Zealanders in the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wi ...

operating from British carriers. The ''Achilles'' left the fleet for Manus Island on 10 August. ''Gambia'' was off Tokyo on VJ day, and was attacked by a Japanese plane while flying the "Cease hostilities" signal – with assistance from surrounding ships, ''Gambia'' shot down the aircraft but was hit by the debris.

The ''Gambia'' represented New Zealand at the surrender ceremonies in Tokyo Bay (2 September 1945), and stayed as part of the occupation force. Air Vice-Marshal Isitt signed the surrender document on behalf of New Zealand. By the end of the war the RNZN had 60 vessels, most of them light craft.

Royal New Zealand Air Force in World War II

European theatre

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

the RNZAF

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeal ...

had as its primary equipment 30 Vickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its ...

bombers, which the New Zealand government offered to the United Kingdom in August 1939, together with the crews to fly them. These formed the nucleus of No. 75 Squadron, the first of the Dominion squadrons to serve with the RAF during the war.

Many other New Zealanders also served in the RAF. As New Zealand did not require its personnel to serve with RNZAF squadrons, the rate at which they entered service was faster than for other Dominions. About 100 RNZAF pilots had been sent to Europe by the time the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

started, and several had a notable role in it.

The RNZAF's primary role took advantage of New Zealand's distance from the conflict by training aircrew as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), or Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a massive, joint military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zea ...

, alongside the other major former British colonies, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. Many New Zealanders did their advanced training in Canada. Local enterprises manufactured or assembled large numbers of De Havilland Tiger Moth

The de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth is a 1930s British biplane designed by Geoffrey de Havilland and built by the de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other operators as a primary trainer aircraf ...

, Airspeed Oxford

The Airspeed AS.10 Oxford is a twin-engine monoplane aircraft developed and manufactured by Airspeed. It saw widespread use for training British Commonwealth aircrews in navigation, radio-operating, bombing and gunnery roles throughout the Seco ...

and North American Harvard

The North American Aviation T-6 Texan is an American single-engined advanced trainer aircraft used to train pilots of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), United States Navy, Royal Air Force, Royal Canadian Air Force and other air forces ...

training aircraft, and the RNZAF also acquired second-hand biplanes such as Hawker Hinds and Vickers Vincents, as well as other types for specialised training such as Avro Anson

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engined, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) ...

s and Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus f ...

es. Only when German surface-raiders became active did the military authorities realise the need for a combat force in New Zealand in addition to the trainers.

New Zealand squadrons of the RAF

Once trained, the majority of RNZAF aircrew served with ordinary units of the RAF or of the

Once trained, the majority of RNZAF aircrew served with ordinary units of the RAF or of the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wi ...

. As in World War I, they served in all theatres. At least 78 became aces. New Zealanders in the RNZAF and RAF included pilots such as the first RAF ace of WW2, Flying Officer Cobber Kain, Alan Deere

Air Commodore Alan Christopher Deere, (12 December 1917 – 21 September 1995) was a New Zealand fighter ace with the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War. He was also known for several near-death experiences over the course ...

, whose ''Nine Lives'' was one of the first post war accounts of combat, and leaders such as World War I ace, Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, who commanded 11 Group, responsible for the defence of London in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, the air defence of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and in the closing stages of the war, the RAF in South East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

. Through accident or design, several RAF units came to be mostly manned by RNZAF pilots (for example No. 243 Squadron RAF

No. 243 Squadron was a flying squadron of the Royal Air Force. Originally formed in August 1918 from two flights that had been part of the Royal Naval Air Service, the squadron conducted anti-submarine patrols during the final stages of World War ...

in Singapore, No. 258 Squadron RAF

No. 258 Squadron was a Royal Air Force squadron during the First and Second World Wars.

History First World War

No. 258 Squadron was first formed 25 July 1918 from 523, 525 and 529 Special Duties Flights at Luce Bay near Stranraer, Scotland und ...

in the UK and several Wildcat and Hellcat units of the FAA – leading some texts to claim these types of aircraft were used by the RNZAF).

Short Stirling

The Short Stirling was a British four-engined heavy bomber of the Second World War. It has the distinction of being the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The Stirling was designed during t ...

s, Avro Lancaster

The Avro Lancaster is a British Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to the same specification, as well as the Short Stir ...

s and Avro Lincoln

The Avro Type 694 Lincoln is a British four-engined heavy bomber, which first flew on 9 June 1944. Developed from the Avro Lancaster, the first Lincoln variants were initially known as the Lancaster IV and V; these were renamed Lincoln I and I ...

s. Other New Zealand squadrons within the RAF included 485, which flew Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Gri ...

s throughout the war, 486

__NOTOC__

Year 486 (Roman numerals, CDLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Basilius and Longinus (or, less freq ...

(Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness b ...

s, Hawker Typhoon

The Hawker Typhoon is a British single-seat fighter-bomber, produced by Hawker Aircraft. It was intended to be a medium-high altitude interceptor, as a replacement for the Hawker Hurricane, but several design problems were encountered and i ...

s and Hawker Tempest

The Hawker Tempest is a British fighter aircraft that was primarily used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Second World War. The Tempest, originally known as the ''Typhoon II'', was an improved derivative of the Hawker Typhoon, intended to a ...

s), 487 (Lockheed Ventura

The Lockheed Ventura is a twin-engine medium bomber and patrol bomber of World War II.

The Ventura first entered combat in Europe as a bomber with the RAF in late 1942. Designated PV-1 by the United States Navy (US Navy), it entered combat in 1 ...

s and De Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its frame was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden ...

es), 488

__NOTOC__

Year 488 ( CDLXXXVIII) was a leap year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Ecclesius and Sividius (or, less frequently, year 1241 ' ...

(Brewster Buffalo

The Brewster F2A Buffalo is an American fighter aircraft which saw service early in World War II. Designed and built by the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation, it was one of the first U.S. monoplanes with an arrestor hook and other modificatio ...

es, Hurricanes, Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufort ...

s and De Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its frame was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden ...

es), 489

__NOTOC__

Year 489 ( CDLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Probinus and Eusebius (or, less frequently, year 1242 ' ...

(Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until ...

s, Bristol Beauforts, Handley Page Hampden