Military history of Iceland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a brief overview of historical warfare and recent developments in

In the period from the settlement of Iceland, in the 870s, until it became part of the realm of the Norwegian King, military defences of Iceland consisted of multiple chieftains (''Goðar'') and their free followers (''þingmenn'', ''bændur'' or ''liðsmenn'') organised as per standard Nordic military doctrine of the time in expeditionary armies such as the ''leiðangr''. These armies were divided into units by the quality of the warriors and birth. At the end of this period the number of chieftains had diminished and their power had grown to the detriment of their followers. This resulted in a long series of major feuds known as

In the period from the settlement of Iceland, in the 870s, until it became part of the realm of the Norwegian King, military defences of Iceland consisted of multiple chieftains (''Goðar'') and their free followers (''þingmenn'', ''bændur'' or ''liðsmenn'') organised as per standard Nordic military doctrine of the time in expeditionary armies such as the ''leiðangr''. These armies were divided into units by the quality of the warriors and birth. At the end of this period the number of chieftains had diminished and their power had grown to the detriment of their followers. This resulted in a long series of major feuds known as

Peace barely ensued as the Norwegian King had little capacity to enforce his will over the Atlantic Ocean, his navy, although the most powerful Atlantic navy at the time was too small to carry big enough invasion force all the way to Iceland. The native Nobles continued to maintain their elite troops, which were called ''sveinalið'' while the '' sýslumenn'' (sheriffs), most of which were noble descendants of the chieftains, maintained soldiers or ''sveinar'' for the defence duties that had been delegated to them by law. All inhabitants of a ''sýslumaður''´s

Peace barely ensued as the Norwegian King had little capacity to enforce his will over the Atlantic Ocean, his navy, although the most powerful Atlantic navy at the time was too small to carry big enough invasion force all the way to Iceland. The native Nobles continued to maintain their elite troops, which were called ''sveinalið'' while the '' sýslumenn'' (sheriffs), most of which were noble descendants of the chieftains, maintained soldiers or ''sveinar'' for the defence duties that had been delegated to them by law. All inhabitants of a ''sýslumaður''´s

Since the king of Denmark had embraced

Since the king of Denmark had embraced

In the decades before the

In the decades before the

In 1918 Iceland regained sovereignty as a separate Kingdom ruled by the Danish king. Iceland established a Coast Guard shortly after, but financial difficulties made establishing a standing army impossible. The government hoped that permanent neutrality would shield the country from invasions. But at the onset of the

In 1918 Iceland regained sovereignty as a separate Kingdom ruled by the Danish king. Iceland established a Coast Guard shortly after, but financial difficulties made establishing a standing army impossible. The government hoped that permanent neutrality would shield the country from invasions. But at the onset of the

The

The

Icelandic Coast Guard

Icelandic National Police

Iceland Air Defence System

Ministry of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs

Ministry for Foreign Affairs

{{Military history of Europe

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

. Iceland has never participated in a full-scale war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

or invasion and the constitution of Iceland has no mechanism to declare war.

Settlement and commonwealth

In the period from the settlement of Iceland, in the 870s, until it became part of the realm of the Norwegian King, military defences of Iceland consisted of multiple chieftains (''Goðar'') and their free followers (''þingmenn'', ''bændur'' or ''liðsmenn'') organised as per standard Nordic military doctrine of the time in expeditionary armies such as the ''leiðangr''. These armies were divided into units by the quality of the warriors and birth. At the end of this period the number of chieftains had diminished and their power had grown to the detriment of their followers. This resulted in a long series of major feuds known as

In the period from the settlement of Iceland, in the 870s, until it became part of the realm of the Norwegian King, military defences of Iceland consisted of multiple chieftains (''Goðar'') and their free followers (''þingmenn'', ''bændur'' or ''liðsmenn'') organised as per standard Nordic military doctrine of the time in expeditionary armies such as the ''leiðangr''. These armies were divided into units by the quality of the warriors and birth. At the end of this period the number of chieftains had diminished and their power had grown to the detriment of their followers. This resulted in a long series of major feuds known as Age of the Sturlungs

The Age of the Sturlungs or the Sturlung Era ( is, Sturlungaöld ) was a 42–44 year period of violent internal strife in mid-13th century Iceland. It is documented in the Sturlunga saga. This period is marked by the conflicts of local chieftai ...

in the 13th century. During and before the war more than 21 fortresses were built.

The battle consisted of little less than 1000 men with the average casualty rate of 15%. This low casualty rate has been attributed to the blood- feud mentality that permeated Icelandic society, which meant that the defeated army could not be slaughtered honourably to a man. As well as the requirements of Christianity to get a pardon from a cleric for each fiend smitten, which resulted in only people of low class taking care of executions. While executions after battle were uncommon, they were extensive when they happened. See, for instance the battle of Haugsnes with about 110 fatalities, Flóabardagi

The Battle of the Gulf () was a naval battle on 25 June 1244 in Iceland's Húnaflói Bay, during the Age of the Sturlungs civil war. The conflicting parties were the followers of Þórður kakali Sighvatsson and those of Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson. ...

with about 80 fatalities on one side and unknown on the other and the battle of Örlygsstaðir

The Battle of Örlygsstaðir was a historic battle fought by the Sturlungar against the Ásbirningar and the Haukdælir clans in northern Iceland. The battle was part of the civil war that was taking place in Iceland at the time between various ...

with up to 60 fatalities including executions. These three battles, or skirmishes as they would be called in a European context add up to 250 fatalities, so these three encounters alone add up to almost 6 of the average killings of 7 per year in the period 1220–1262. Years could pass without killings.

Amphibious operations were important parts of warfare in Iceland in this time, especially in the Westfjords, while large naval engagement

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

s were not common. The largest of these was an engagement of a few dozen ships in Húnaflói

Húnaflói (, "Huna Bay") is a large bay between Strandir and Skagaströnd in Iceland. It is about wide and long. The towns Blönduós and Skagaströnd are located on the bay's eastern side.

Fauna

The bay has been proposed as a protecte ...

known as Flóabardagi

The Battle of the Gulf () was a naval battle on 25 June 1244 in Iceland's Húnaflói Bay, during the Age of the Sturlungs civil war. The conflicting parties were the followers of Þórður kakali Sighvatsson and those of Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson. ...

. One side employing smaller longship

Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by the Nors ...

s as well as boats and the other large Knaars, other larger merchant ships and ferries. Although neither side expected to do battle at sea, the battle was fought in a fairly standard way for the time, the ships being bound together, starting with archery and rock throwing, then spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

hurling and ending in a melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

all over the fleet, ships being exchanged by each side many times.

At first the chieftains relied primarily on peasant levies but as the war progressed and Norwegian military influences became more pronounced, their personal retinues expanded and became more professional. At the end most of the chieftains had been slain and only one of the original chieftains who started the war remained. It had nonetheless become evident that no one chieftain was powerful enough to vanquish all the others and ensure peace. This led the Icelandic ''betri bændur'' (better farmers or farmer leaders) of the South, North and Western Iceland to submit to the Norwegian crown and the Alþingi in 1262. Two years later in 1264 the Lords of Eastern Iceland, the '' Svínfellingar'', submitted as well, but the Eastern Region had completely escaped the ravages of war, mostly because of its geographical barriers of wastelands, mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually highe ...

s and glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s.

Union with Norway

Peace barely ensued as the Norwegian King had little capacity to enforce his will over the Atlantic Ocean, his navy, although the most powerful Atlantic navy at the time was too small to carry big enough invasion force all the way to Iceland. The native Nobles continued to maintain their elite troops, which were called ''sveinalið'' while the '' sýslumenn'' (sheriffs), most of which were noble descendants of the chieftains, maintained soldiers or ''sveinar'' for the defence duties that had been delegated to them by law. All inhabitants of a ''sýslumaður''´s

Peace barely ensued as the Norwegian King had little capacity to enforce his will over the Atlantic Ocean, his navy, although the most powerful Atlantic navy at the time was too small to carry big enough invasion force all the way to Iceland. The native Nobles continued to maintain their elite troops, which were called ''sveinalið'' while the '' sýslumenn'' (sheriffs), most of which were noble descendants of the chieftains, maintained soldiers or ''sveinar'' for the defence duties that had been delegated to them by law. All inhabitants of a ''sýslumaður''´s fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

were obligated to follow them in battle against invaders.

The king rarely asked for expeditionary forces to help defend Norway, although Icelanders in Norway had been obligated to help Norwegian defences since the early 12th century. There are however a few documented occasions of Icelandic expeditionary armies coming to the king's aid.

As the church became more powerful its bishops and priests became more militant: at the peak of their power the two bishops could command armies consisting of over 6% of Iceland's total population. The Bishops' own ''sveinar'' could expect to become priests after their military service. The two bishops became ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' Ecclesiastical Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

s or ''Kirkjugreifar'', responsible for law enforcement and overall command of military defences. Icelandic noblemen became wary of the Bishops' powers in the late 15th century and protested. During the 15th century, when English traders and fishermen started to come to Iceland, it became a common practice among chieftains to buy cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s for defence against foreign ships and for internal conflicts. Other firearms, such as the hand gonne, known as ''haki'' or ''hakbyssa'' in Iceland, became popular as well.

Lutheranism

Since the king of Denmark had embraced

Since the king of Denmark had embraced Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

in the early 16th century he had campaigned to convert his realms from Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

to Lutheranism. In the 1540s it was Iceland's turn: a Lutheran bishop was elected as the bishop of Skálholt

Skálholt (Modern Icelandic: ; non, Skálaholt ) is a historical site in the south of Iceland, at the river Hvítá.

History

Skálholt was, through eight centuries, one of the most important places in Iceland. A bishopric was established in Sk� ...

diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associa ...

and bitter conflict ensued. Although the bloodshed didn't come close to that in the Civil War fought in the 13th century, it was still considerable as the bishops fielded armies of thousands, and even fought at Alþingi.

In a bid to isolate Skálholt, Iceland's last Catholic bishop, Jón Arason

Jón Arason (1484 – November 7, 1550) was an Icelandic Roman Catholic bishop and poet, who was executed in his struggle against the imposition of the Protestant Reformation in Iceland.

Background

Jón Arason was born in Gryta, educated at Mu ...

of Hólar

Hólar (; also Hólar í Hjaltadal ) is a small community in the Skagafjörður district of northern Iceland.

Location

Hólar is in the Hjaltadalur valley, some from the national capital of Reykjavík. It has a population of around 100. It is th ...

, attempted to cut its lines of communication to the Westfjords by invading the lands of Daði Guðmundsson

Daði Guðmundsson ( – 1563) or Daði of Snóksdal was a farmer and magistrate in 16th century Iceland. He lived in the town of Snóksdalur in Dalasýsla county and played an important role in the Battle of Sauðafell and the Lutheran Reform ...

. Although initially successful in capturing '' Sauðafell'' he was later defeated by Daði's army and captured with his sons. Jón Arason and his sons were then transported to Skálholt and beheaded there in 1550. A year later a Danish mercenary force mostly consisting of Landsknecht

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front lin ...

s arrived to support the policy of conversion. Although no open warfare continued, the Danish king was still wary of an insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

and ordered the destruction of all Icelandic arms and armor. Further mercenary armies, consisting of Landsknecht

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front lin ...

s, are sent to carry out these orders over the following years. After that starts a period where Royal Danish forces are responsible for the defence of Iceland. The Royal Dano-Norwegian Navy patrols the coasts of Iceland, but mostly to prevent illegal trading rather than piracy. Some Icelandic sheriffs, however, manage to continue to maintain considerable retinues, especially in the Westfjords, where the Landsknechts were not as thorough in their search.

Pirate raids

The lack of weaponry among Icelanders made them more vulnerable topirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

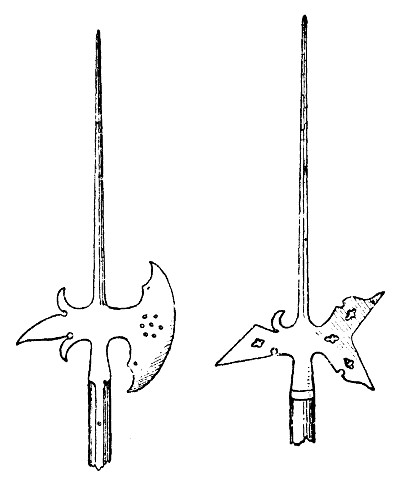

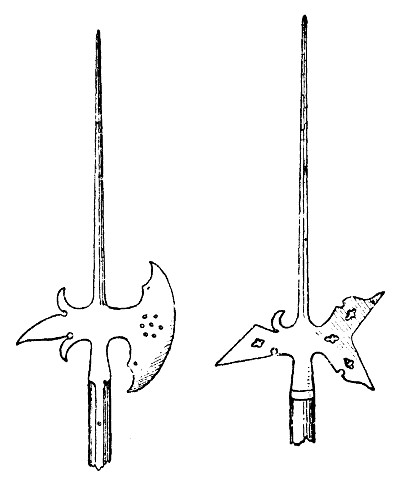

attacks than before, although in some places, such as the aforementioned Westfjords, Icelanders managed to massacre foreign pirates. Icelandic officials complained about the raids in letters to the king and as a result many halberd

A halberd (also called halbard, halbert or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. The word ''halberd'' is cognate with the German word ''Hellebarde'', deriving from ...

s were sent to Iceland by Royal edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Pro ...

. The halberd, known as ''atgeir'' or ''arngeir'' in Icelandic, became a signature weapon of Icelandic farmers. The king remained wary of the Icelanders, and refused to supply them with firearms. As most of the pirates were well armed with such weapons it made defence difficult. However some old guns and cannons still remained and could be used against their ships.

In 1627 Icelanders were shocked at the inability of the Danish forces to protect them against Barbary corsairs who murdered and kidnapped a large number of people. In some places Danish troops fled from the raiders, but the Captain (''Höfuðsmaður'') of Iceland, who was the highest-ranking military officer and overall governor of Iceland, managed to defend Bessastaðir

Bessastaðir () is the official residence of the president of Iceland. It is situated in Álftanes, about from the capital city, Reykjavík

Reykjavík ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland, ...

by hastily building fortifications and damaged one of the raiding ships severely with cannon fire. Some Icelanders were nonetheless angered that he didn't sink the ship despite it being stuck for 24 hours on a reef in front of the fortifications. As a result, Icelanders formed local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s with the king's blessing in places such as Vestmannaeyjar

Vestmannaeyjar (, sometimes anglicized as Westman Islands) is a municipality and archipelago off the south coast of Iceland.

The largest island, Heimaey, has a population of 4,414, most of whom live in the archipelago's main town, Vestmannaeyj ...

.

18th and 19th centuries

Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the king declared his intention to send considerable amount of money to arm the Icelandic militias with muskets. However, his pledges were not fully fulfilled and in 1799 the few hundred militia-men in the South West of Iceland were mostly equipped with rusty and mostly obsolete Medieval weaponry, including 16th century halberds. When English raiders arrived in 1808, after sinking or capturing most of the Danish-Norwegian Navy in the Battle of Copenhagen, the amount of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

in Iceland was so low that it prohibited all efforts of the governor of Iceland, Count Trampe, to provide any resistance.

In 1855, the Icelandic Army was reestablished by Andreas August von Kohl the sheriff in Vestmannaeyjar

Vestmannaeyjar (, sometimes anglicized as Westman Islands) is a municipality and archipelago off the south coast of Iceland.

The largest island, Heimaey, has a population of 4,414, most of whom live in the archipelago's main town, Vestmannaeyj ...

. In 1856, the king provided 180 rixdollars to buy guns, and a further 200 rixdollars the following year. The sheriff became the Captain of the new army, which become known as ''Herfylkingin'', "The Battalion."

In 1860, von Kohl died, and Pétur Bjarnasen took over the command. Nine years later Pétur Bjarnasen died before appointing a successor, and the army fell into disarray.

Many have campaigned for an Icelandic standing army since the late 19th century, including Iceland's Independence hero Jón Sigurðsson

Jón Sigurðsson (17 June 1811 – 7 December 1879) was the leader of the 19th century Icelandic independence movement.

Biography

Born at Hrafnseyri, in Arnarfjörður in the Westfjords area of Iceland, he was the son of Þórdís Jónsdótti ...

, but except for the attempt in 1940 it has amounted to little.

Independence

In 1918 Iceland regained sovereignty as a separate Kingdom ruled by the Danish king. Iceland established a Coast Guard shortly after, but financial difficulties made establishing a standing army impossible. The government hoped that permanent neutrality would shield the country from invasions. But at the onset of the

In 1918 Iceland regained sovereignty as a separate Kingdom ruled by the Danish king. Iceland established a Coast Guard shortly after, but financial difficulties made establishing a standing army impossible. The government hoped that permanent neutrality would shield the country from invasions. But at the onset of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the government, becoming justifiably nervous, decided to expand the capabilities of the National Police National Police may refer to the national police forces of several countries:

*Afghanistan: Afghan National Police

*Haiti: Haitian National Police

*Colombia: National Police of Colombia

*Cuba: Cuban National Police

*East Timor: National Police of ...

(''Ríkislögreglan'') and its reserves into a military unit. Chief Commissioner of Police Agnar Kofoed Hansen had been trained in the Danish Air Force and he moved swiftly to train his officers. Weapons and uniforms were acquired and near Laugarvatn

Laugarvatn () is the name of a lake and a small town in the south of Iceland. The lake is smaller than the neighbouring Apavatn.

Tourism

Laugarvatn lies within the Golden Circle, a popular tourist route, and acts as a staging post. The town has ...

they practiced rifle shooting and military tactics. Agnar barely managed to train his 60 officers before the United Kingdom invaded Iceland on May 10, 1940. The next step in the drive towards militarisation was to have been the training of the 300 strong reserve forces, but the invasion effectively stopped it.

Second World War

Cod Wars

The

The Cod Wars

The Cod Wars ( is, Þorskastríðin; also known as , ; german: Kabeljaukriege) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Each of ...

, also called the Icelandic Cod Wars (Icelandic: ''Þorskastríðin'', "the cod war", or ''Landhelgisstríðin'', "the war for the territorial waters"), were a series of three confrontations from the 1950s to the 1970s between the United Kingdom and Iceland over fishing rights in the North Atlantic. None of the Cod Wars meet any of the common thresholds for a conventional war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

, and they may more accurately be described as militarised interstate disputes.

The First Cod War lasted from 1 September until 12 November 1958. It began as soon as a new Icelandic law that expanded the Icelandic fishery zone from , came into force at midnight of 1 September. After a number of rammings and a few shots fired between the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and Icelandic patrol boats, Britain and Iceland came to a settlement, which stipulated that any future disagreement between Iceland and Britain in the matter of fishery zones would be sent to the International Court of Justice in the Hague. The First Cod War saw a total of 37 Royal Navy ships and 7,000 sailors protecting the fishing fleet from six Icelandic gunboats and their 100 coast guards.

The Second Cod War between the United Kingdom and Iceland lasted from September 1972 until the signing of a temporary agreement in November 1973. In 1972, Iceland unilaterally declared an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending beyond its territorial waters, before announcing plans to reduce overfishing. It policed its quota system with the Icelandic Coast Guard, leading to a series of net-cutting incidents with British trawlers that fished the areas. As a result, the Royal Navy deployed warships and tugboats to act as a deterrent against any future harassment of British fishing crews by the Icelandic craft, resulting in direct confrontations between Icelandic patrol vessels and British warships, which again included ramming incidents. After a series of talks within NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, British warships were recalled on 3 October 1973. An agreement was signed on 8 November which limited British fishing activities to certain areas inside the limit, resolving the dispute that time. The resolution was based on the premise that British trawlers would limit their annual catch to no more than 130,000 tons. This agreement expired in November 1975, and the third "Cod War" began.

The Third Cod War lasted from November 1975 to June 1976. Iceland had declared that the ocean up to from its coast fell under Icelandic authority. The British government did not recognise this large increase to the exclusion zone, and as a result, there were again almost daily rammings between Icelandic patrol vessels and British trawlers, frigates and tugboats. The dispute eventually ended in 1976 after Iceland threatened to close a major NATO base in retaliation for Britain's deployment of naval vessels within the disputed limit. The British government conceded, and agreed that after 1 December 1976 British trawlers would not fish within the previously disputed area.

NATO and the Cold War

Iceland's main contribution to theNATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

defence effort, during the Cold War was the rent-free provision of the "agreed areas"—sites for military facilities. By far the largest and most important of these was the NATO Naval Air Station Keflavík

Naval Air Station Keflavik (NASKEF) was a United States Navy station at Keflavík International Airport, Iceland, located on the Reykjanes peninsula on the south-west portion of the island. NASKEF was closed on 8 September 2006, and its facilitie ...

, manned by American, Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

, Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

, Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

personnel. Units from these and other NATO countries also are deployed temporarily to Keflavík

Keflavík (pronounced , meaning ''Driftwood Bay'') is a town in the Reykjanes region in southwest Iceland. It is included in the municipality of Reykjanesbær whose population as of 2016 is 15,129.

In 1995, Keflavik merged with nearby Njarð ...

, and they stage practice operations. Many of these practices were anti-submarine warfare patrols, but these exercises were halted when the P-3 ASW aircraft were withdrawn from Keflavík.

Iceland and the United States regarded the U.S. military presence since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

as a cornerstone to bilateral foreign/security policy. The presence of the troops was negotiated under a treaty known as the Agreed Minute.

Talks about the American presence were restarted as of 2005, since the U.S. government was keen on deploying its troops and equipment to parts of the world with more pressing need for them. Proposals by the Icelandic government included a complete Icelandic takeover of the Airbase, as well as replacing the Pavehawk rescue helicopter unit with a detachment from the aeronautical half of the Icelandic Coast Guard

The Icelandic Coast Guard (, or simply ) is the Icelandic defence service responsible for search and rescue, maritime safety and security surveillance, and law enforcement in the seas surrounding Iceland. The Coast Guard maintains the Iceland ...

, in exchange for the continued stationing of the four F-15C

The McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle is an American twin-engine, all-weather tactical fighter aircraft designed by McDonnell Douglas (now part of Boeing). Following reviews of proposals, the United States Air Force selected McDonnell Douglas's ...

interceptors in Keflavík.

On March 15, 2006 the U.S. government announced that the Iceland Defense Force

The Iceland Defense Force ( is, Varnarlið Íslands; IDF) was a military command of the United States Armed Forces from 1951 to 2006. The IDF, created at the request of NATO, came into existence when the United States signed an agreement to p ...

would be withdrawn by the end of September 2006. The last American troops left on September 30, handing control of the Keflavík base over to the Sheriff of Keflavík airport, who was to be in charge of it on behalf of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

American withdrawal

On September 26, 2006 the Government of Iceland released a document containing Iceland's response to the withdrawal of American forces. It included plans (a) to create a Security and Defense authority to oversee all security organisations in Iceland, includingPolice

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and th ...

and Coast Guard; (b) to increase the capabilities of the Coast Guard by purchasing vessels and aircraft; (c) to create a Security or Secret service; and (d) to establish a secure communications system spanning the whole country. MP Magnús Þór Hafsteinsson of the Liberal party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

voiced his party's willingness to raise a standing army, in agreement with views expressed by Björn Bjarnason

Björn Bjarnason (born 14 November 1944) is an Icelandic politician. His father was Bjarni Benediktsson, Prime Minister of Iceland, Minister of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs and Mayor of Reykjavík.

Matriculating from Reykjavík Junior ...

Minister of Justice and Ecclesiastical affairs.

The Icelandic Defence Agency (''Varnarmálastofnun Íslands'') was founded in 2008 under the Minister for Foreign Affairs. The Agency was to consolidate functions previously served by NATO forces at Naval Air Station Keflavik

Naval Air Station Keflavik (NASKEF) was a United States Navy station at Keflavík International Airport, Iceland, located on the Reykjanes peninsula on the south-west portion of the island. NASKEF was closed on 8 September 2006, and its facilitie ...

, such as maintaining defense installations, intelligence gathering and military exercises. An initial budget of $20 million fell to $13 million in 2009 as the Icelandic economy suffered a crisis. On 30 March 2010, the Icelandic government announced it would legislate to disband the Agency and put its services under the command of the Coast Guard or National Police. To save money and to restore the primary role of the Icelandic Coast Guard in defense, the Defence Agency was shut down on January 1, 2011.

Iceland Air Meet 2014 hosted NATO and other Nordic countries for the first time.

See also

* Battle of Haugsnes *Battle of Sauðafell

The Battle of Sauðafell (''Orrustan á Sauðafelli'') occurred in 1550, when the forces of Catholic Bishop Jón Arason clashed with the forces of Daði Guðmundsson of Snóksdalur.

Location

Sauðafell was an important part of Daði's fief in ...

* Battle of Víðines

*Battle of the Gulf

The Battle of the Gulf () was a naval battle on 25 June 1244 in Iceland's Húnaflói Bay, during the Age of the Sturlungs civil war. The conflicting parties were the followers of Þórður kakali Sighvatsson and those of Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson ...

*Battle of Örlygsstaðir

The Battle of Örlygsstaðir was a historic battle fought by the Sturlungar against the Ásbirningar and the Haukdælir clans in northern Iceland. The battle was part of the civil war that was taking place in Iceland at the time between various ...

* Borgarvirki

* Defence of Iceland

*History of Iceland

The recorded history of Iceland began with the settlement by Viking explorers and the people they enslaved from the east, particularly Norway and the British Isles, in the late ninth century. Iceland was still uninhabited long after the rest ...

*List of countries without armed forces

This is a list of countries without armed forces. The term ''country'' here means sovereign states and not dependencies (e.g., Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Bermuda) whose defense is the responsibility of another country or an army alternative ...

* List of wars involving Iceland

References

Further reading

*Þór Whitehead, ''The Ally who came in from the cold: a survey of Icelandic Foreign Policy 1946–1956'', Centre for International Studies. University of Iceland Press. Reykjavík. 1998.External links

Icelandic Coast Guard

Icelandic National Police

Iceland Air Defence System

Ministry of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs

Ministry for Foreign Affairs

{{Military history of Europe