Mihail Kogălniceanu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a

''Dezrobirea țiganilor, ștergerea privilegiilor boierești, emanciparea țăranilor''

(wikisource) During Milhail Kogălniceanu's lifetime, there was confusion regarding his exact birth year, with several sources erroneously indicating it as 1806; in his speech to the

, in th

, at the

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains''

(wikisource)

''La Monarchie de juillet et les Roumains''

/ref> Among his colleagues was the future philosopher

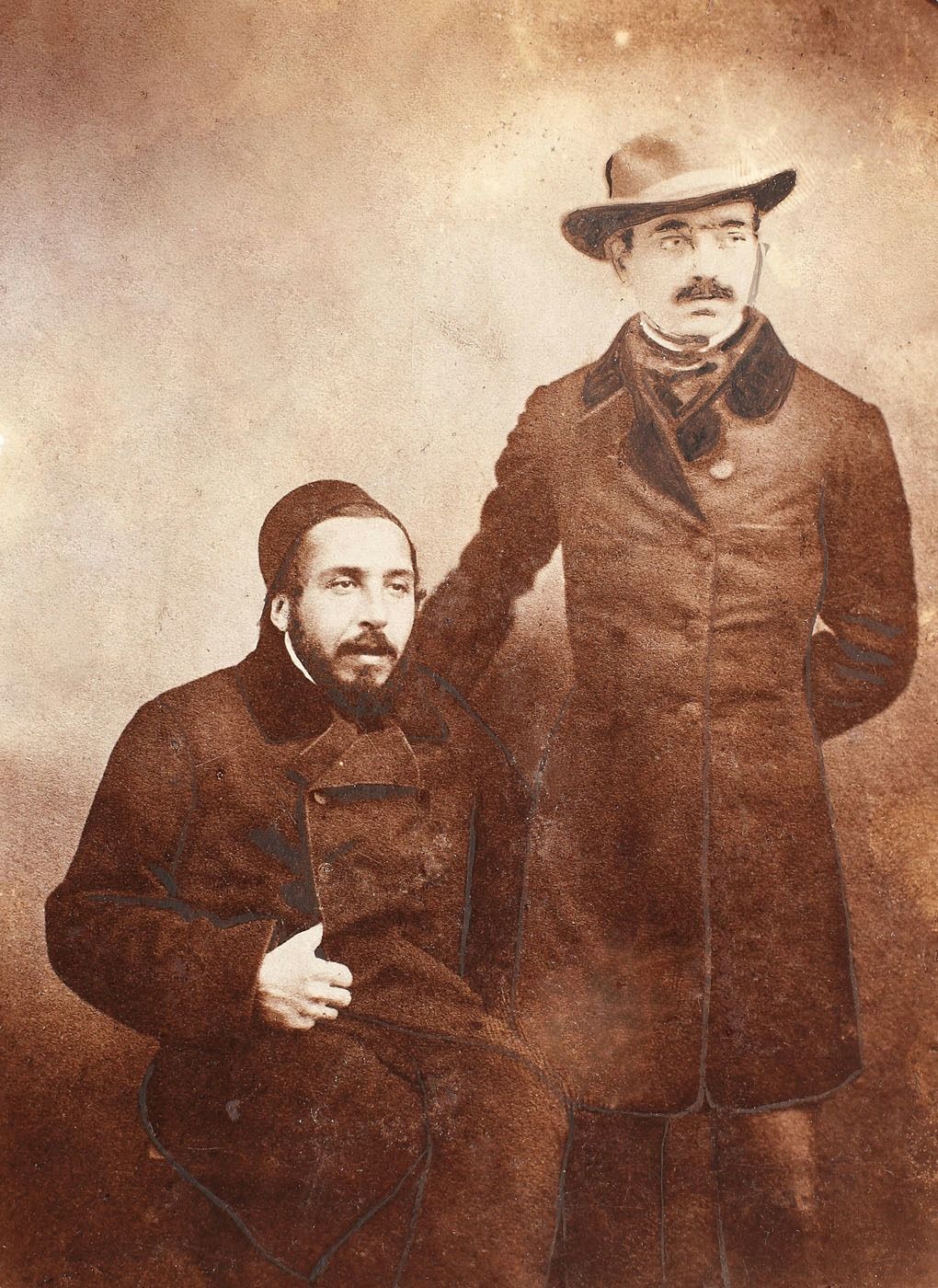

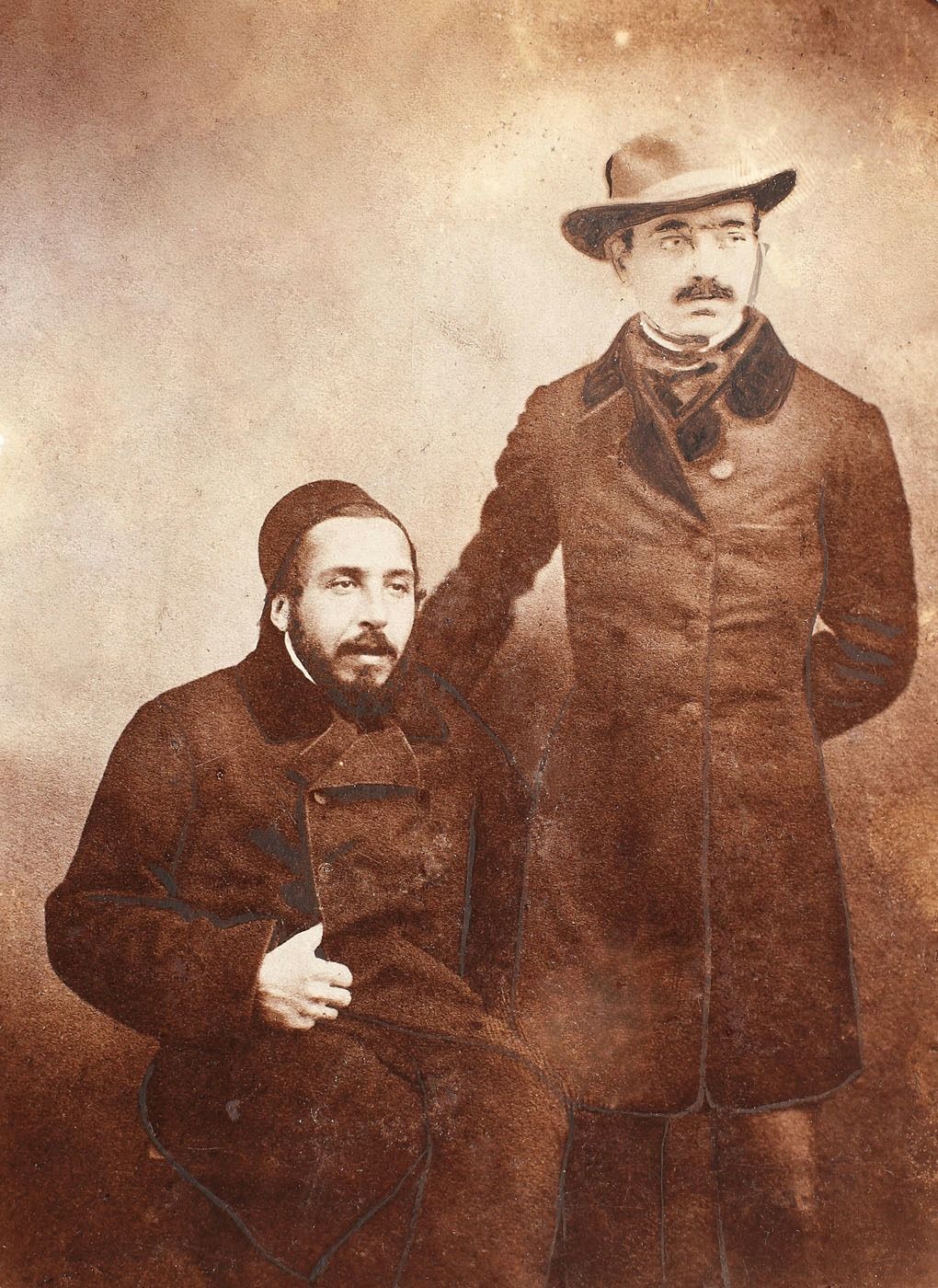

File:Ilie Kogalniceanu.jpg, Ilie Kogălniceanu

File:Catinca Stavilla.jpg, Catinca Stavilla

File:Kogalniceanu youth.jpg, Mihail Kogălniceanu in cadet uniform at age 18

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania

The prime minister of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul României), officially the prime minister of the Government of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul Guvernului României, link=no), is the head of the Government of Romania. Initially, the office was s ...

on October 11, 1863, after the 1859 union of the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th c ...

under ''Domnitor

''Domnitor'' (Romanian pl. ''Domnitori'') was the official title of the ruler of Romania between 1862 and 1881. It was usually translated as "prince" in other languages and less often as "grand duke". Derived from the Romanian word "''domn'' ...

'' Alexandru Ioan Cuza

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (, or Alexandru Ioan I, also anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was the first ''domnitor'' (Ruler) of the Romanian Principalities through his double election as prince of Moldavia on 5 Janua ...

, and later served as Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

under Carol I

Carol I or Charles I of Romania (20 April 1839 – ), born Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, was the monarch of Romania from 1866 to his death in 1914, ruling as Prince (''Domnitor'') from 1866 to 1881, and as King from 1881 to 1914. He w ...

. He was several times Interior Minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

under Cuza and Carol. A polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, Kogălniceanu was one of the most influential Romanian intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator o ...

s of his generation. Siding with the moderate liberal current for most of his lifetime, he began his political career as a collaborator of Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. ...

Mihail Sturdza, while serving as head of the Iași Theater and issuing several publications together with the poet Vasile Alecsandri

Vasile Alecsandri (; 21 July 182122 August 1890) was a Romanian patriot, poet, dramatist, politician and diplomat. He was one of the key figures during the 1848 revolutions in Moldavia and Wallachia. He fought for the unification of the Romani ...

and the activist Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica (; 12 August 1816 – 7 May 1897) was a Romanian statesman, mathematician, diplomat and politician, who was Prime Minister of Romania five times. He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president many times (1876–1882, ...

. After editing the highly influential magazine ''Dacia Literară

''Dacia Literară'' was the first Romanian literary and political journal.

History

Founded by Mihail Kogălniceanu and printed in Iaşi, Dacia Literară was a Romantic nationalist and liberal magazine, engendering a literary society

A lit ...

'' and serving as a professor at '' Academia Mihăileană'', Kogălniceanu came into conflict with the authorities over his Romantic nationalist inaugural speech of 1843. He was the ideologue of the abortive 1848 Moldavian revolution

The Moldavian Revolution of 1848 is the name used for the unsuccessful Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist movement inspired by the Revolutions of 1848 in the principality of Moldavia. Initially seeking accommodation within the political f ...

, authoring its main document, ''Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova''.

Following the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

(1853–1856), with Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica

Grigore Alexandru Ghica or Ghika (1803 or 1807 – 24 August 1857) was a Prince of Moldavia between 14 October 1849, and June 1853, and again between 30 October 1854, and 3 June 1856. His wife was Helena, a member of the Sturdza family and dau ...

, Kogălniceanu was responsible for drafting legislation to abolish Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Together with Alecsandri, he edited the unionist magazine '' Steaua Dunării'', played a prominent part during the elections for the ad hoc Divan

The two Ad hoc Divans were legislative{{cn, date=February 2017 and consultative assemblies of the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia), vassals of the Ottoman Empire. They were established by the Great Powers under the Treaty of Par ...

, and successfully promoted Cuza, his lifelong friend, to the throne. Kogălniceanu advanced legislation to revoke traditional ranks and titles, and to secularize the property of monasteries. His efforts at land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

resulted in a censure vote, leading Cuza to enforce them through a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' in May 1864. However, Kogălniceanu resigned in 1865, following his own conflicts with the monarch.

A decade after, he helped create the National Liberal Party, before playing an important part in Romania's decision to enter the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878—a choice which consecrated her independence. He was also instrumental in the acquisition, and later colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

, of Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( ro, Dobrogea de Nord or simply ; bg, Северна Добруджа, ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube river and the Black Sea, bordered in the south ...

region. During his final years, he was a prominent member and one-time President of the Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its byl ...

, and briefly served as Romanian representative to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

Biography

Early life

Born inIași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

, he belonged to the Kogălniceanu family

The House of Kogălniceanu, Kogălniceanul or Cogâlniceanu (; ro, Familia Kogălniceanu, ''Kogălniceni'' or ''Kogălnicenii''; Francized ''de Kogalnitchan'') was one of the major political, intellectual and aristocratic families in Moldavia, ...

of Moldavian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

s, being the son of ''Vornic

Vornic was a historical rank for an official in charge of justice and internal affairs. He was overseeing the Royal Court. It originated in the Slovak '' nádvorník''. In the 16th century in Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literall ...

'' Ilie Kogălniceanu, and the great-grandson of Constantin Kogălniceanu (noted for having signed his name to a 1749 document issued by Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos

Constantine Mavrocordatos (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Μαυροκορδάτος, Romanian: ''Constantin Mavrocordat''; February 27, 1711November 23, 1769) was a Greek noble who served as Prince of Wallachia and Prince of Moldavia at several ...

, through which serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

was disestablished in Moldavia). Mihail's mother, Catinca née Stavilla (or Stavillă), was, according to Kogălniceanu's own words, " roma Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

** Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditiona ...

family in Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

".Gorovei, p.6 The author took pride in noting that "my family has never searched its origins in foreign countries or peoples". Nevertheless, in a speech he gave shortly before his death, Kogălniceanu commented that Catinca Stavilla had been the descendant of "a Genoese family, settled for centuries in the Genoese colony of Cetatea Albă

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi ( uk, Бі́лгород-Дністро́вський, Bílhorod-Dnistróvskyy, ; ro, Cetatea Albă), historically known as Akkerman ( tr, Akkerman) or under different names, is a city, municipality and port situated on ...

(Akerman), whence it then scattered throughout Bessarabia". Mihail Kogălniceanu''Dezrobirea țiganilor, ștergerea privilegiilor boierești, emanciparea țăranilor''

(wikisource) During Milhail Kogălniceanu's lifetime, there was confusion regarding his exact birth year, with several sources erroneously indicating it as 1806; in his speech to the

Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its byl ...

, he acknowledged this, and gave his exact birth date as present in a register kept by his father. It was also then that he mentioned his godmother was Marghioala Calimach, a Callimachi

The House of Callimachi, Calimachi, or Kallimachi ( el, Καλλιμάχη, russian: Каллимаки, tr, Kalimakizade; originally ''Calmașul'' or ''Călmașu''), was a Phanariote family of mixed Moldavian (Romanian) and Greek origins. Origina ...

boyaress who married into the Sturdza family

The House of Sturdza, Sturza or Stourdza is the name of an old Moldavian noble family, whose origins can be traced back to the 1540s and whose members played important political role in the history of Moldavia, Russia and later Romania.

Political ...

, and was the mother of Mihail Sturdza (Kogălniceanu's would-be protector and foe).

Kogălniceanu was educated at Trei Ierarhi monastery in Iași, before being tutored by Gherman Vida, a monk who belonged to the Transylvanian School

The Transylvanian School ( ro, Școala Ardeleană) was a cultural movement which was founded after part of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Habsburg-ruled Transylvania accepted the leadership of the pope and became the Greek-Catholic Church (). The ...

, and who was an associate of Gheorghe Șincai

Gheorghe Șincai (; February 28, 1754 – November 2, 1816) was a Romanian historian, philologist, translator, poet, and representative of the Enlightenment-influenced Transylvanian School.

As the director of Greek Catholic education in Transy ...

. He completed his primary education in Miroslava, where he attended the Cuénim boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of " room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exte ...

.Anineanu, p.62; Gorovei, p.9; Maciu, p.66 It was during this early period that he first met the poet Vasile Alecsandri

Vasile Alecsandri (; 21 July 182122 August 1890) was a Romanian patriot, poet, dramatist, politician and diplomat. He was one of the key figures during the 1848 revolutions in Moldavia and Wallachia. He fought for the unification of the Romani ...

(they studied under both Vida and Cuénim), Costache Negri

Costache Negri (May 14, 1812 – September 28, 1876) was a Moldavian, later Romanian writer, politician, and revolutionary.

Born in Iași, he was the son of ''vistiernic'' (treasurer) Petrache Negre. The scion of a boyar family, he was educated ...

and Cuza."Mihail Kogălniceanu", in th

, at the

Ohio University

Ohio University is a public research university in Athens, Ohio. The first university chartered by an Act of Congress and the first to be chartered in Ohio, the university was chartered in 1787 by the Congress of the Confederation and subse ...

; retrieved November 29, 2011 At the time, Kogălniceanu became a passionate student of history, beginning his investigations into old Moldavian chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and ...

s.Gorovei, p.9

With support from Prince Sturdza, Kogălniceanu continued his studies abroad, originally in the French city of Lunéville

Lunéville ( ; German, obsolete: ''Lünstadt'' ) is a commune in the northeastern French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

It is a subprefecture of the department and lies on the river Meurthe at its confluence with the Vezouze.

History

L ...

(where he was cared for by Sturdza's former tutor, the ''abbé

''Abbé'' (from Latin ''abbas'', in turn from Greek , ''abbas'', from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is the title for low ...

'' Lhommé), and later at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

. Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains''

(wikisource)

''La Monarchie de juillet et les Roumains''

/ref> Among his colleagues was the future philosopher

Grigore Sturdza

Grigore Mihail Sturdza, first name also Grigorie or Grigori, last name also Sturza, Stourdza, Sturd̦a, and Stourza (also known as Muklis Pasha, George Mukhlis, and Beizadea Vițel; May 11, 1821 – January 26, 1901), was a Moldavian, later Romani ...

, son of the Moldavian monarch. His stay in Lunéville was cut short by the intervention of Russian officials, who were supervising Moldavia under the provisions of the ''Regulamentul Organic

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual na ...

'' regime, and who believed that, through the influence of Lhommé (a participant in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

), students were being infused with rebellious ideas; all Moldavian students, including Sturdza's sons and other noblemen, were withdrawn from the school in late 1835, and reassigned to Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

education institutions.

In Berlin

During his period inBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, he came in contact with and was greatly influenced by Friedrich Carl von Savigny

Friedrich Carl von Savigny (21 February 1779 – 25 October 1861) was a German jurist and historian.

Early life and education

Savigny was born at Frankfurt am Main, of a family recorded in the history of Lorraine, deriving its name from the cast ...

, Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

, Eduard Gans, and especially Professor Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis ...

,Vianu, Vol.II, p.273-277 whose ideas on the necessity for politicians to be acquainted with historical science he readily adopted. In pages he dedicated to the influence exercised by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

on Romanian thought, Tudor Vianu

Tudor Vianu (; January 8, 1898 – May 21, 1964) was a Romanian literary critic, art critic, poet, philosopher, academic, and translator. He had a major role on the reception and development of Modernism in Romanian literature and art. He was m ...

noted that certain Hegelian

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

-related principles were a common attribute of the Berlin faculty during Kogălniceanu's stay. He commented that, in later years, the politician adopted views which resonated with those of Hegel, most notably the principle that legislation needed to adapt to the individual spirit of nations.

Kogălniceanu later noted with pride that he had been the first of Ranke's Romanian students, and claimed that, in conversations with Humboldt, he was the first person to use the modern equivalents French-language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in No ...

of the words "Romanian" and "Romania" (''roumain'' and ''Roumanie'')—replacing the references to "Moldavia(n)" and " Wallachia(n)", as well as the antiquated versions used before him by the intellectual Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi (, surname also spelled Asaki; 1 March 1788 – 12 November 1869) was a Moldavian, later Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist, engineer- border maker and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and ...

; historian Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

also noted the part Kogălniceanu played in popularizing these references as the standard ones.

Kogălniceanu was also introduced to Frederica, Duchess of Cumberland, and became relatively close to her son George of Cumberland and Teviotdale, the future ruler of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

. Initially hosted by a community of the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

, he later became the guest of a Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

named Jonas, in whose residence he witnessed gatherings of activists in favor of German unification

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of t ...

(''see Burschenschaft

A Burschenschaft (; sometimes abbreviated in the German ''Burschenschaft'' jargon; plural: ) is one of the traditional (student associations) of Germany, Austria, and Chile (the latter due to German cultural influence).

Burschenschaften were fo ...

''). According to his own recollections, his group of Moldavians was kept under close watch by Alexandru Sturdza, who, in addition, enlisted Kogălniceanu's help in writing his work ''Études historiques, chrétiennes et morales'' ("Historical, Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

and Moral Studies"). During summer trips to the Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

n town of Heringsdorf

Heringsdorf is a semi-urban municipality and a popular seaside resort on Usedom Island in Western Pomerania, Germany. It is also known by the name Kaiserbad ('' en, Imperial Spa'').

The municipality was formed in January 2005 out of the former ...

, he met the novelist Willibald Alexis

Willibald Alexis, the pseudonym of Georg Wilhelm Heinrich Häring (29 June 179816 December 1871), was a German historical novelist, considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Life

Alexis was born in Breslau, Silesia. His father, who cam ...

, whom he befriended, and who, as Kogălniceanu recalled, lectured him on the land reform carried out by Prussian King

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman ...

Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

. Later, Kogălniceanu studied the effects of reform when on visit to Alt Schwerin

Alt Schwerin () is a municipality in the Mecklenburgische Seenplatte district, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV; ; nds, Mäkelborg-Vörpommern), also known by its anglicized name Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, is a st ...

, and saw the possibility for replicating its results in his native country.

Greatly expanding his familiarity with historical and social subjects, Kogălniceanu also began work on his first volumes: a pioneering study on the Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic Itinerant groups in Europe, itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have Ro ...

and the French-language ''Histoire de la Valachie, de la Moldavie et des Valaques transdanubiens'' ("A History of Wallachia, Moldavia, and of Transdanubian Vlachs", the first volume in a synthesis of Romanian history

This article covers the history and bibliography of Romania and links to specialized articles.

Prehistory

34,950-year-old remains of modern humans with a possible Neanderthalian trait were discovered in present-day Romania when the ''Peș ...

), both of which were first published in 1837 inside the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

. He was becoming repulsed by the existence of Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in his country, and in his study, cited the example of active abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

in Western countries.

In addition, he authored a series of studies on Romanian literature

Romanian literature () is literature written by Romanian authors, although the term may also be used to refer to all literature written in the Romanian language.

History

The development of the Romanian literature took place in parallel with tha ...

. He signed these first works with a Francized version of his name, ''Michel de Kogalnitchan'' ("Michael of Kogalnitchan"), which was slightly erroneous (it used the partitive case

The partitive case ( abbreviated , , or more ambiguously ) is a grammatical case which denotes "partialness", "without result", or "without specific identity". It is also used in contexts where a subgroup is selected from a larger group, or with n ...

twice: once in the French particle "de", and a second time in the Romanian-based suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns, adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can carr ...

"-an").

Raising the suspicions of Prince Sturdza after it became apparent that he sided with the reform-minded youth of his day in opposition to the ''Regulamentul Organic'' regime, Kogălniceanu was prevented from completing his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

, and instead returned to Iași, where he became a princely adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

in 1838.

In opposition to Prince Sturdza

Over the following decade, he published a large number of works, including essays and articles, his first editions of the Moldavian chroniclers, as well as other books and articles, while founding a succession of short-lived periodicals: ''Alăuta Românească'' (1838), ''Foaea Sătească a Prințipatului Moldovei'' (1839), ''Dacia Literară

''Dacia Literară'' was the first Romanian literary and political journal.

History

Founded by Mihail Kogălniceanu and printed in Iaşi, Dacia Literară was a Romantic nationalist and liberal magazine, engendering a literary society

A lit ...

'' (1840), ''Arhiva Românească'' (1840), ''Calendar pentru Poporul Românesc'' (1842), ''Propășirea'' (renamed ''Foaie Științifică și Literară'', 1843), and several almanac

An almanac (also spelled ''almanack'' and ''almanach'') is an annual publication listing a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, tide tables, and othe ...

s. In 1844, as a Moldavian law freed some slaves in Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church

* Oriental Orthodox Churches

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church of New Zealand

* State church of the Roman Empire

* True Orthodox church

See also

* Orthodox (d ...

property, his articles announced a great triumph for "humanity" and "new ideas".

Both ''Dacia Literară'' and ''Foaie Științifică'', which he edited together with Alecsandri, Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica (; 12 August 1816 – 7 May 1897) was a Romanian statesman, mathematician, diplomat and politician, who was Prime Minister of Romania five times. He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president many times (1876–1882, ...

, and Petre Balș, were suppressed by Moldavian authorities, who considered them suspect. Together with Costache Negruzzi, he printed all of Dimitrie Cantemir

Dimitrie or Demetrius Cantemir (, russian: Дмитрий Кантемир; 26 October 1673 – 21 August 1723), also known by other spellings, was a Romanian prince, statesman, and man of letters, regarded as one of the most significant e ...

's works available at the time, and, in time, acquired his own printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, which planned to issue the complete editions of Moldavian chronicles, including those of Miron Costin

Miron Costin (March 30, 1633 – 1691) was a Moldavian (Romanian) political figure and chronicler. His main work, ''Letopiseţul Ţărâi Moldovei e la Aron Vodă încoace' (''The Chronicles of the land of Moldavia Aron Vodă">Aron_Tiranul.h ...

and Grigore Ureche

Grigore Ureche (; 1590–1647) was a Moldavian chronicler who wrote on Moldavian history in his ''Letopisețul Țării Moldovei'' ('' Chronicles of the Land of Moldavia''), covering the period from 1359 to 1594.

Biography

Grigore Ureche was th ...

(after many disruptions associated with his political choices, the project was fulfilled in 1852). In this context, Kogălniceanu and Negruzzi sought to Westernize

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the '' Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, econ ...

the Moldavian public, with interest ranging as far as Romanian culinary tastes: the almanacs published by them featured gourmet

Gourmet (, ) is a cultural idea associated with the culinary arts of fine food and drink, or haute cuisine, which is characterized by refined, even elaborate preparations and presentations of aesthetically balanced meals of several contrasting, of ...

-themed aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by ...

s and recipes meant to educate local folk about the refinement and richness of European cuisine

European cuisine comprises the cuisines of Europe "European Cuisine."Grigorescu, p.20-21 Kogălniceanu would later claim that he and his friend were "originators of the

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

(wikisource)

''Amestec de curente contradictorii: G. Asachi''

/ref> Mihail Kogălniceanu later issued clear criticism of Asachi's proposed version of literary Romanian, which relied on

''Poezia românească în epoca lui Asachi și Eliade''

(wikisource) Tensions also occurred between Kogălniceanu and Alecsandri, after the former began suspecting his collaborator of having reduced and toned down his contributions to ''Foaie Științifică''.Anineanu, p.64 During this period, Kogălniceanu maintained close contacts with his former colleague

Around 1843, Kogălniceanu's enthusiasm for change was making him a suspect to the Moldavian authorities, and his lectures on History were suspended in 1844. His

Around 1843, Kogălniceanu's enthusiasm for change was making him a suspect to the Moldavian authorities, and his lectures on History were suspended in 1844. His

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains''

(wikisource)

''La Révolution de 1848 et les émigrés''

/ref> In its 10 sections and 120 articles, the manifesto called for, among other things, internal autonomy,

In April 1849, part of the goals of the 1848 Revolution were fulfilled by the

In April 1849, part of the goals of the 1848 Revolution were fulfilled by the

Interrupted by Russian and Austrian interventions during the Crimean War, his activity as ''Partida Națională'' representative was successful after the 1856 Treaty of Paris, when Moldavia and Wallachia came under the direct supervision of the European Powers (comprising, alongside Russia and Austria, the

Interrupted by Russian and Austrian interventions during the Crimean War, his activity as ''Partida Națională'' representative was successful after the 1856 Treaty of Paris, when Moldavia and Wallachia came under the direct supervision of the European Powers (comprising, alongside Russia and Austria, the

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains''

(wikisource)

''La guerre de Crimée et la fondation de l'Etat roumain''

/ref> By that time, he was in correspondence with Jean Henri Abdolonyme Ubicini, a French essayist and traveler who had played a minor part in the Wallachian uprising, and who supported the Romanian cause in his native country. Elected by the

From 1859 to 1865, Kogălniceanu was on several occasions the cabinet leader in the Moldavian half of the United Principalities, then

From 1859 to 1865, Kogălniceanu was on several occasions the cabinet leader in the Moldavian half of the United Principalities, then

''Domnitor'' Cuza was ultimately ousted by a coalition of Conservatives and Liberals in February 1866; following a period of transition and maneuvers to avert international objections, a perpetually unified

''Domnitor'' Cuza was ultimately ousted by a coalition of Conservatives and Liberals in February 1866; following a period of transition and maneuvers to avert international objections, a perpetually unified

Serving as

Serving as

"Moldavian and Western Interpretations of Modern Romanian History"

"Portrete ale oamenilor politici români de la sfârșitul secolului al XIX-lea în documente diplomatice germane"

, in the

"«La Californie des Roumains»: L’intégration de la Dobroudja du Nord à la Roumanie, 1878–1913"

i

Nr. 1-2/2002 Contrarily, with his proclamation to the peoples of Northern Dobruja, Kogălniceanu enshrined the standard

Kogălniceanu subsequently represented his country in France (1880), being the first Romanian envoy to Paris, and having Alexandru Lahovary on his staff. The French state awarded him its Legion of Honour, with the rank of ''Grand Officier''. In January 1880 – 1881, Kogălniceanu oversaw the first diplomatic contacts between Romania and Qing Dynasty, Qing China, as an exchange of correspondence between the Romanian Embassy to France and Zeng Jize, the Chinese Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Upon his return to the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Romania, Kogălniceanu played a prominent part in opposing further concessions for Austria, on the issue of Internationalization of the Danube River, international Danube navigation. By 1883, he was becoming known as the speaker of a Liberal conservatism, liberal conservative faction of the National Liberal group. Kogălniceanu and his supporters criticized Rosetti and others who again pushed for Universal male suffrage, universal (male) suffrage, and argued that Romania's fragile international standing did not permit electoral divisiveness.

After withdrawing from political life, Kogălniceanu served as Romanian Academy President from 1887 to 1889 (or 1890). Having fallen severely ill in 1886, he spent his final years editing historical documents of the Eudoxiu Hurmuzaki fund, publicizing Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek and Roman Empire, Roman archeological finds in Northern Dobruja, and collecting foreign documents related to

Kogălniceanu subsequently represented his country in France (1880), being the first Romanian envoy to Paris, and having Alexandru Lahovary on his staff. The French state awarded him its Legion of Honour, with the rank of ''Grand Officier''. In January 1880 – 1881, Kogălniceanu oversaw the first diplomatic contacts between Romania and Qing Dynasty, Qing China, as an exchange of correspondence between the Romanian Embassy to France and Zeng Jize, the Chinese Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Upon his return to the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Romania, Kogălniceanu played a prominent part in opposing further concessions for Austria, on the issue of Internationalization of the Danube River, international Danube navigation. By 1883, he was becoming known as the speaker of a Liberal conservatism, liberal conservative faction of the National Liberal group. Kogălniceanu and his supporters criticized Rosetti and others who again pushed for Universal male suffrage, universal (male) suffrage, and argued that Romania's fragile international standing did not permit electoral divisiveness.

After withdrawing from political life, Kogălniceanu served as Romanian Academy President from 1887 to 1889 (or 1890). Having fallen severely ill in 1886, he spent his final years editing historical documents of the Eudoxiu Hurmuzaki fund, publicizing Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek and Roman Empire, Roman archeological finds in Northern Dobruja, and collecting foreign documents related to

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

(wikisource)

''Recunoașterea necesității criticii. Cauzele pentru care spiritul critic apare în Moldova''

/ref> German statesmen were however disinclined to consider him one of their own: Bernhard von Bülow took for granted rumors that he was an agent of the Russians, and further alleged that the Romanian land reform was a sham. Supportive of constitutionalism, civil liberties, and other liberal positions, Kogălniceanu prioritized the nation over individualism, an approach with resonated with the tendencies of all his fellow Moldavian revolutionaries. In maturity, Kogălniceanu had become a skeptic with respect to the

"The 'Judaisation' of the Enemy in the Romanian Political Culture at the Beginning of the 20th Century"

, in the Babeș-Bolyai University's

Studia Judaica

'', 2007, p.139-140 The more radical antisemite and National Liberal Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu expressed much criticism of this moderate stance (which he also believed was represented within the party by Rosetti and

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

(wikisource)

''Veacul al XIX-lea. Factorii culturii românești din acest veac''

/ref> To illustrate this view, he cited Kogălniceanu's ''Cuvânt pentru deschiderea cursului de istorie națională'', which notably states:

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

(wikisource)

''Evoluția spiritului critic – Deosebirile dintre vechea școală critică moldovenească și "Junimea"''

/ref> The latter conclusion was partly shared by Călinescu,

Mihail Kogălniceanu was married to Ecaterina Jora (1827–1907), the widow of Iorgu Scorțescu, a Moldavian military forces, Moldavian Militia colonel; they had more than eight children together (three of whom were boys). The eldest son, Constantin, studied Law and had a career in diplomacy, being the author of an unfinished work on Romanian history. Ion, his brother, was born in 1859 and died in 1892, being the only one of Mihail Kogălniceanu's male children to have heirs. His line was still surviving in 2001.Guțanu, p.8 Ion's son, also named Mihail, established the ''Mihail Kogălniceanu Cultural Foundation'' in 1935 (in 1939–1946, it published a magazine named ''Arhiva Românească'', which aimed to be a new series of the one published during the 1840s; its other projects were rendered ineffectual by the outbreak of World War II).Gorovei, p.60

Vasile Kogălniceanu, the youngest son, was noted for his involvement in Agrarianism, agrarian and left-wing politics during the early 20th century. A founder of ''Partida Țărănească'' (which served as an inspiration for the Peasants' Party (Romania), Peasants' Party after 1918), he was a collaborator of Vintilă Rosetti in campaigning for the universal suffrage and legislating Sunday rest. A manifesto to the peasants, issued by him just before the Peasants' Revolt of 1907, was interpreted by the authorities as a call to rebellion, and led to Kogălniceanu's imprisonment for a duration of five months. A member of the Chamber of Deputies of Romania, Chamber of Deputies for Ilfov County, he served as a ''rapporteur'' for the Alexandru Averescu executive during the 1921 debates regarding an extensive land reform.

Vasile's sister Lucia (or Lucie) studied at a

Mihail Kogălniceanu was married to Ecaterina Jora (1827–1907), the widow of Iorgu Scorțescu, a Moldavian military forces, Moldavian Militia colonel; they had more than eight children together (three of whom were boys). The eldest son, Constantin, studied Law and had a career in diplomacy, being the author of an unfinished work on Romanian history. Ion, his brother, was born in 1859 and died in 1892, being the only one of Mihail Kogălniceanu's male children to have heirs. His line was still surviving in 2001.Guțanu, p.8 Ion's son, also named Mihail, established the ''Mihail Kogălniceanu Cultural Foundation'' in 1935 (in 1939–1946, it published a magazine named ''Arhiva Românească'', which aimed to be a new series of the one published during the 1840s; its other projects were rendered ineffectual by the outbreak of World War II).Gorovei, p.60

Vasile Kogălniceanu, the youngest son, was noted for his involvement in Agrarianism, agrarian and left-wing politics during the early 20th century. A founder of ''Partida Țărănească'' (which served as an inspiration for the Peasants' Party (Romania), Peasants' Party after 1918), he was a collaborator of Vintilă Rosetti in campaigning for the universal suffrage and legislating Sunday rest. A manifesto to the peasants, issued by him just before the Peasants' Revolt of 1907, was interpreted by the authorities as a call to rebellion, and led to Kogălniceanu's imprisonment for a duration of five months. A member of the Chamber of Deputies of Romania, Chamber of Deputies for Ilfov County, he served as a ''rapporteur'' for the Alexandru Averescu executive during the 1921 debates regarding an extensive land reform.

Vasile's sister Lucia (or Lucie) studied at a

"Bijuterii mortale"

, in ''Ieșeanul'', March 7, 2006 He died in 1904, leaving his wife a large fortune, which she spent on a large collection of jewels and fortune-telling séances. Adela Kogălniceanu was robbed and murdered in October 1920; rumor had it that she had been killed by her own son, but this path was never pursued by authorities, who were quick to cancel the investigation (at the time, they were faced with Labor movement in Romania, the major strikes of 1920).

Mihail Kogălniceanu's residence in Iași is kept as a memorial house and public museum. His vacation house in the city, located in Copou area and known locally as ''Casa cu turn'' ("The House with a Tower"), was the residence of composer George Enescu for part of the Romanian Campaign (World War I), Romanian Campaign, and, in 1930, was purchased by the novelist Mihail Sadoveanu (in 1980, it became a museum dedicated to Sadoveanu's memory). Adrian Pârvu

Mihail Kogălniceanu's residence in Iași is kept as a memorial house and public museum. His vacation house in the city, located in Copou area and known locally as ''Casa cu turn'' ("The House with a Tower"), was the residence of composer George Enescu for part of the Romanian Campaign (World War I), Romanian Campaign, and, in 1930, was purchased by the novelist Mihail Sadoveanu (in 1980, it became a museum dedicated to Sadoveanu's memory). Adrian Pârvu

"Casa cu turn din Copou"

, in ''

''Mărturii românești peste hotare: creații românești și izvoare despre români în colecții din străinătate. II: Finlanda – Grecia''

Editura Biblioteca Bucureștilor, Bucharest, 2011. *Charles Upson Clark, ''United Roumania'', Ayer Publishing, Manchester, New Hampshire, 1971. *Neagu Djuvara, ''Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne'', Humanitas publishing house, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995. * Constantin Gheorghe, Miliana Șerbu

''Miniștrii de interne (1862–2007). Mică enciclopedie''

Ministry of Administration and Interior (Romania), Romanian Ministry of the Interior, 2007 * Maura G. Giura, Lucian Giura

"Otto von Bismarck și românii"

in the 1 Decembrie 1918 University, Alba Iulia, December 1 University of Alba Iulia ''Annales Universitatis Apulensis, Series Historica (AUASH)'', Nr. 2–3, 1998–1999, p. 161–175 *Constantin C. Giurescu, ''Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre'', Editura Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966. *Dan Grigorescu, preface to Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, Brillat-Savarin, ''Fiziologia gustului'', Editura Meridiane, Bucharest, 1988, p. 5–22 *Ștefan Gorovei, "Kogălnicenii", in ''Magazin Istoric'', July 1977, p. 6–10, 60 * Laura Guțanu

"Valori de patrimoniu. Lucia Kogălniceanu"

in the University of Iași Central Library ''Biblos'', Nr. 11-12 (2001), p. 8–9 *Vasile Maciu, "Costache Negri, un ctitor al României moderne", in ''Magazin Istoric'', May 1975, p. 66–69 *William Norton Medlicott, ''The Congress of Berlin and After'', Routledge, London, 1963. *Z. Ornea, **''Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească'', Editura Fundației Culturale Române, Bucharest, 1995. **''Junimea și junimismul'', Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1998. *Laurence Senelick, ''National Theatre in Northern and Eastern Europe, 1746–1900'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991. *L. S. Stavrianos, Leften Stavros Stavrianos, ''The Balkans since 1453'', C. Hurst & Co, London, 2000. *

"Les dilemmes, les controverses et les conséquences d'une alliance politique conjecturale. Les relations roumaino-russes des années 1877–1878"

in the Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava]

''Codrul Cosminului''

Nr. 14 (2008), p. 77–117 *D. Gh. Vitcu, "Cuza în exil. Puterea dragostei de țară", in ''Magazin Istoric'', May 1973, p. 18–22

* Ion Creangă

''Moș Ion Roată''

at wikisource

''Independența României''

an

''Războiul Independenței''

at the Internet Movie Database

Frescoes

at the Romanian Athenaeum site {{DEFAULTSORT:Kogalniceanu, Mihail 1817 births 1891 deaths Prime Ministers of Romania Romanian Ministers of Foreign Affairs Romanian Ministers of Interior Romanian Ministers of Agriculture Romanian Ministers of Public Works Prime Ministers of the Principality of Moldavia Members of the Ad hoc Divans Members of the Chamber of Deputies (Romania) Recipients of the Order of the Star of Romania Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Christian abolitionists Moldavian abolitionists Romanian independence activists European classical liberals Conservatism in Romania National Liberal Party (Romania) politicians Presidents of the Romanian Academy Romanian book publishers (people) Writers from Iași 19th-century Romanian dramatists and playwrights Male dramatists and playwrights 19th-century essayists Male essayists Romanian essayists 19th-century Romanian historians Romanian literary critics Romanian printers Romanian revolutionaries 19th-century Romanian lawyers 19th-century journalists Male journalists Romanian magazine editors Romanian magazine founders Romanian food writers 19th-century memoirists Romanian memoirists Romanian theatre managers and producers Romanian travel writers Romanian writers in French Politicians from Iași Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church Romanian Freemasons Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Romani history in Romania People of the Revolutions of 1848 Romanian people of the Crimean War Romanian people of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) Burials at Eternitatea cemetery

culinary art

Culinary arts are the cuisine arts of food preparation, cooking and presentation of food, usually in the form of meals. People working in this field – especially in establishments such as restaurants – are commonly called che ...

in Moldavia".Grigorescu, p.21

With ''Dacia Literară'', Kogălniceanu began expanding his Romantic ideal of "national specificity", which was to be a major influence on Alexandru Odobescu

Alexandru Ioan Odobescu (; 23 June 1834 – 10 November 1895) was a Romanian author, archaeologist and politician.

Biography

He was born in Bucharest, the second child of General Ioan Odobescu and his wife Ecaterina. After attending Saint Sav ...

and other literary figures. One of the main goals his publications had was expanding the coverage of modern Romanian culture

The culture of Romania is an umbrella term used to encapsulate the ideas, customs and social behaviours of the people of Romania that developed due to the country's distinct geopolitical history and evolution. It is theorized and speculated that ...

beyond its early stages, during which it had mainly relied on publishing translations of Western literature

Western literature, also known as European literature, is the literature written in the context of Western culture in the languages of Europe, as well as several geographically or historically related languages such as Basque and Hungarian, an ...

—according to Garabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian- Armenian literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, University of Iași professor (1908–1934), and, together with Paul Bujor and Constantin Stere, fo ...

, this was accompanied by a veiled attack on Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi (, surname also spelled Asaki; 1 March 1788 – 12 November 1869) was a Moldavian, later Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist, engineer- border maker and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and ...

and his '' Albina Românească''. Garabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian- Armenian literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, University of Iași professor (1908–1934), and, together with Paul Bujor and Constantin Stere, fo ...

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

(wikisource)

''Amestec de curente contradictorii: G. Asachi''

/ref> Mihail Kogălniceanu later issued clear criticism of Asachi's proposed version of literary Romanian, which relied on

archaism

In language, an archaism (from the grc, ἀρχαϊκός, ''archaïkós'', 'old-fashioned, antiquated', ultimately , ''archaîos'', 'from the beginning, ancient') is a word, a sense of a word, or a style of speech or writing that belongs to a hi ...

s and Francized phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

s, notably pointing out that it was inconsistent. Additionally, he evidenced the influence foreign poetry had on Asachi's own work, viewing it as excessive. Paul Zarifopol

Paul Zarifopol (November 30, 1874 – May 1, 1934) was a Romanian literary and social critic, essayist, and

literary historian. The scion of an aristocratic family, formally trained in both philology and the sociology of literature, he em ...

''Poezia românească în epoca lui Asachi și Eliade''

(wikisource) Tensions also occurred between Kogălniceanu and Alecsandri, after the former began suspecting his collaborator of having reduced and toned down his contributions to ''Foaie Științifică''.Anineanu, p.64 During this period, Kogălniceanu maintained close contacts with his former colleague

Costache Negri

Costache Negri (May 14, 1812 – September 28, 1876) was a Moldavian, later Romanian writer, politician, and revolutionary.

Born in Iași, he was the son of ''vistiernic'' (treasurer) Petrache Negre. The scion of a boyar family, he was educated ...

and his sister Elena, becoming one of the main figures of the intellectual circle hosted by the Negris in Mânjina. He also became close to the French teacher and essayist Jean Alexandre Vaillant, who was himself involved in liberal causes while being interested in the work of Moldavian chroniclers.Ioana Ursu, "J. A. Vaillant, un prieten al poporului român", in ''Magazin Istoric

''Magazin Istoric'' ( en, The Historical Magazine) is a Romanian monthly magazine.

Overview

''Magazin Istoric'' was started in 1967. The first issue appeared in April 1967. The headquarters is in Bucharest. The monthly magazine contains articles ...

'', July 1977, p.15 Intellectuals of the day speculated that Kogălniceanu later contributed several sections to Vaillant's lengthy essay about Moldavia and Wallachia (''La Roumanie'').

In May 1840, while serving as Prince Sturdza's private secretary, he became co-director (with Alecsandri and Negruzzi) of the National Theater Iași. This followed the monarch's decision to unite the two existing theaters in the city, one of which hosted plays in French, into a single institution. In later years, this venue, which staged popular comedies based on the French repertory of its age and had become the most popular of its kind in the country, also hosted Alecsandri's debut as a playwright. Progressively, it also became subject to Sturdza's censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

.

In 1843, Kogălniceanu gave a celebrated inaugural lecture on national history at the newly founded '' Academia Mihăileană'' in Iași, a speech which greatly influenced ethnic Romanian students at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

and the 1848 generation (''see Cuvânt pentru deschiderea cursului de istorie națională''). Other professors at the ''Academia'', originating in several historical regions

Historical regions (or historical areas) are geographical regions which at some point in time had a cultural, ethnic, linguistic or political basis, regardless of latterday borders. They are used as delimitations for studying and analysing so ...

, were Ion Ghica, Eftimie Murgu

Eftimie Murgu (28 December 1805 – 12 May 1870) was a Romanian philosopher and politician who took part in the 1848 Revolutions.

Biography

He was born in Rudăria (today Eftimie Murgu, Caraș-Severin County) to Samu Murgu, an officer in the I ...

, and Ion Ionescu de la Brad. Kogălniceanu's introductory speech was partly prompted by Sturdza's refusal to give him ''imprimatur

An ''imprimatur'' (sometimes abbreviated as ''impr.'', from Latin, "let it be printed") is a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement. The imprimatur rule in the R ...

'', and amounted to a revolutionary project.Călinescu, p.77 Among other things, it made explicit references to the common cause of Romanians living in the two states of Moldavia and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

, as well as in Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

- and Russian-ruled areas:

"I view as my country everywhere on earth where Romanian is spoken, and as national history the history of all of Moldavia, that of Wallachia, and that of our brothers inTransylvania Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...."

Revolution

Around 1843, Kogălniceanu's enthusiasm for change was making him a suspect to the Moldavian authorities, and his lectures on History were suspended in 1844. His

Around 1843, Kogălniceanu's enthusiasm for change was making him a suspect to the Moldavian authorities, and his lectures on History were suspended in 1844. His passport

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that contains a person's identity. A person with a passport can travel to and from foreign countries more easily and access consular assistance. A passport certifies the personal ...

was revoked while he was traveling to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

as the secret representative of the Moldavian political opposition (attempting to approach Metternich and discuss Sturdza's ouster). Briefly imprisoned after returning to Iași, he soon after became involved in political agitation in Wallachia, assisting his friend Ion Ghica: in February, during a Romantic nationalist celebration, he traveled to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

, where he met members of the secretive ''Frăția'' organization and of its legal front, ''Soțietatea Literară'' (including Ghica, Nicolae Bălcescu

Nicolae Bălcescu () (29 June 181929 November 1852) was a Romanian Wallachian soldier, historian, journalist, and leader of the 1848 Wallachian Revolution.

Early life

Born in Bucharest to a family of low-ranking nobility, he used his mother ...

, August Treboniu Laurian __NOTOC__

August Treboniu Laurian (; 17 July 1810 – 25 February 1881) was a Transylvanian Romanian politician, historian and linguist. He was born in the village of Hochfeld, Principality of Transylvania, Austrian Empire (today Fofeldea as par ...

, Alexandru G. Golescu

Alexandru G. Golescu (1819 – 15 August 1881) was a Romanian politician who served as a Prime Minister of Romania in 1870.

Life

Early life

Born in the Golescu family of boyars in Bucharest, Wallachia, he was the cousin of the brothers Ștef ...

, and C. A. Rosetti

Constantin Alexandru Rosetti (; 2 June 1816 – 8 April 1885) was a Romanian literary and political leader, born in Bucharest into the princely Rosetti family.

Biography Before 1848

Constantin Alexandru Rosetti was born in Bucharest, the so ...

).

Having sold his personal library to ''Academia Mihăileană'', Eugen Denize, , in ''Tribuna

''Tribuna'' (russian: Трибуна) is a weekly Russian newspaper that focuses largely on industry and the energy sector.

History

Tribunas published its first publication in July 1969. Until 1990, the newspaper titled the ''Sotsialisticheska ...

'', Nr. 28, November 2003 Kogălniceanu was in Paris and other Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

an cities from 1845 to 1847, joining the Romanian student association (''Societatea Studenților Români'') that included Ghica, Bălcescu, and Rosetti and was presided over by the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869), was a French author, poet, and statesman who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic and the continuation of the Tricolore as the flag of France. ...

. He also frequented ''La Bibliothèque roumaine'' ("The Romanian Library"), while affiliating to the Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and joining the Lodge

Lodge is originally a term for a relatively small building, often associated with a larger one.

Lodge or The Lodge may refer to:

Buildings and structures Specific

* The Lodge (Australia), the official Canberra residence of the Prime Minist ...

known as ''L'Athénée des étrangers'' ("Foreigners' Atheneum"), as did most other reform-minded Romanians in Paris. Vasile Surcel, , in ''Jurnalul Național

''Jurnalul Național'' is a Romanian newspaper, part of the INTACT Media Group led by Dan Voiculescu, which also includes the popular television station Antena 1. The newspaper was launched in 1993. Its headquarters is in Bucharest

Buchare ...

'', October 11, 2004 In 1846, he visited Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, wishing to witness the wedding of Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

and the Duke of Cádiz

The Dukedom of Cádiz is a title of Spanish nobility. Its name refers to the Andalusian city of Cádiz.

History

Rodrigo Ponce de León was a Castilian military leader who was granted the title of Duke of Cádiz in 1484. After the death of the ...

, but he was also curious to assess developments in Spanish culture

The culture of ''Spain'' is based on a variety of historical influences, primarily based on the culture of ancient Rome, Spain being a prominent part of the Greco-Roman world for centuries, the very name of Spain comes from the name that the ...

. Upon the end of his trip, he authored ''Notes sur l'Espagne'' ("Notes on Spain"), a French-language volume combining memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

, travel writing

Travel is the movement of people between distant geographical locations. Travel can be done by foot, bicycle, automobile, train, boat, bus, airplane, ship or other means, with or without luggage, and can be one way or round trip. Travel ...

and historiographic record.

For a while, he concentrated his activities on reviewing historical sources, expanding his series of printed and edited Moldavian chronicles. At the time, he renewed his contacts with Vaillant, who helped him publish articles in the ''Revue de l'Orient''. He would later state: "We did not come to Paris just to learn how to speak French like the French do, but also to borrow the ideas and useful things of a nation that is so enlightened and so free".

Following the onset of the European Revolutions, Kogălniceanu was present at the forefront of nationalist politics. Though, for a number of reasons, he failed to sign the March 1848 petition-proclamation which signaled the Moldavian revolution, he was seen as one of its instigators, and Prince Sturdza ordered his arrest during the police roundup that followed. While evading capture, Kogălniceanu authored some of the most vocal attacks on Sturdza, and, by July, a reward was offered for his apprehension "dead or alive". During late summer, he crossed the Austrian border into Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

, where he took refuge on the Hurmuzachi brothers' property (in parallel, the ''Frăția''-led Wallachian revolution managed to gain power in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

).

Kogălniceanu became a member and chief ideologue of the Moldavian Central Revolutionary Committee in exile. His manifesto, ''Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova'' ("The Wishes of the National Party in Moldavia", August 1848), was, in effect, a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

al project listing the goals of Romanian revolutionaries. It contrasted with the earlier demands the revolutionaries had presented to Sturdza, which called for strict adherence to the ''Regulamentul Organic

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual na ...

'' and an end to abuse. Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

''Histoire des relations entre la France et les Roumains''

(wikisource)

''La Révolution de 1848 et les émigrés''

/ref> In its 10 sections and 120 articles, the manifesto called for, among other things, internal autonomy,

civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and political liberties, separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typi ...

, abolition of privilege, an end to ''corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

s'', and a Moldo-Wallachian union. Referring to the latter ideal, Kogălniceanu stressed that it formed:

"the keystone without which the national edifice would crumble".At the same time, he published a more explicit "Project for a Moldavian Constitution", which expanded on how ''Dorințele'' could be translated into reality. Kogălniceanu also contributed articles to the Bukovinian journal ''Bucovina'', the voice of revolution in Romanian-inhabited Austrian lands. In January 1849, a

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

epidemic forced him to leave for the French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he carried on with his activities in support of the Romanian revolution.

Prince Ghica's reforms

In April 1849, part of the goals of the 1848 Revolution were fulfilled by the

In April 1849, part of the goals of the 1848 Revolution were fulfilled by the Convention of Balta Liman

The Convention of Balta Liman of 1 May 1849 was an agreement between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, Ottomans regulating the political situation of the two Danubian Principalities (the basis of present-day Romania), signed during the af ...

, through which the two suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

powers of the ''Regulamentul Organic

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual na ...

'' regime—the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

—appointed Grigore Alexandru Ghica

Grigore Alexandru Ghica or Ghika (1803 or 1807 – 24 August 1857) was a Prince of Moldavia between 14 October 1849, and June 1853, and again between 30 October 1854, and 3 June 1856. His wife was Helena, a member of the Sturdza family and dau ...

, a supporter of the liberal and unionist cause, as Prince of Moldova (while, on the other hand, confirming the defeat of revolutionary power in Wallachia). Ghica allowed the instigators of the 1848 events to return from exile, and appointed Kogălniceanu, as well as Costache Negri

Costache Negri (May 14, 1812 – September 28, 1876) was a Moldavian, later Romanian writer, politician, and revolutionary.

Born in Iași, he was the son of ''vistiernic'' (treasurer) Petrache Negre. The scion of a boyar family, he was educated ...

and Alexandru Ioan Cuza

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (, or Alexandru Ioan I, also anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was the first ''domnitor'' (Ruler) of the Romanian Principalities through his double election as prince of Moldavia on 5 Janua ...

to administrative offices. The measures enforced by the prince, together with the fallout from the defeat of Russia in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, were to bring by 1860 the introduction of virtually all liberal tenets comprised in ''Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova''.

Kogălniceanu was consequently appointed to various high level government positions, while continuing his cultural contributions and becoming the main figure of the loose grouping '' Partida Națională'', which sought the merger of the two Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th c ...

under a single administration. In 1867, reflecting back on his role, he stated: