Midewiwin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Midewiwin (in syllabics: , also spelled ''Midewin'' and ''Medewiwin'') or the Grand Medicine Society is a secretive religion of some of the indigenous peoples of

The Midewiwin (in syllabics: , also spelled ''Midewin'' and ''Medewiwin'') or the Grand Medicine Society is a secretive religion of some of the indigenous peoples of

Hoffman, Walter James. "The Midewiwin, or 'Grand Medicine Society', of the Ojibwa" in ''Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Bureau of Ethnology Report'', v. 7, pp. 149-299. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891).

* Johnston, Basil. "The Society of Medicine\''Midewewin''" in ''Ojibway Ceremonies'', pp. 93–112. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990). *Landes, Ruth. ''Ojibwa Religion and the Midéwiwin''. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968). *Roufs, Tim. ''When Everybody Called Me Gah-bay-bi-nayss: "Forever-Flying-Bird".'' An Ethnographic Biography of Paul Peter Buffalo. (Duluth: University of Minnesota, 2007).

Chapter 30: Midewiwin: Grand Medicine

** ttp://www.d.umn.edu/cla/faculty/troufs/Buffalo/PB33.html Chapter 33: Medicine Men / Medicine Women*Vecsey, Christopher. ''Traditional Ojibwa Religion and its Historical Changes''. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983). *Warren, William W. ''History of the Ojibway People''. (1851) {{Anishinaabe Native American religion Traditional healthcare occupations

The Midewiwin (in syllabics: , also spelled ''Midewin'' and ''Medewiwin'') or the Grand Medicine Society is a secretive religion of some of the indigenous peoples of

The Midewiwin (in syllabics: , also spelled ''Midewin'' and ''Medewiwin'') or the Grand Medicine Society is a secretive religion of some of the indigenous peoples of the Maritimes

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of C ...

, New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

and Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

regions in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

. Its practitioners are called ''Midew'', and the practices of ''Midewiwin'' are referred to as ''Mide''. Occasionally, male ''Midew'' are called ''Midewinini'', which is sometimes translated into English as "medicine man

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective languages, for spiritual healers and cerem ...

".

Etymology

Thepreverb

Although not widely accepted in linguistics, the term preverb is used in Caucasian (including all three families: Northwest Caucasian, Northeast Caucasian and Kartvelian), Caddoan, Athabaskan, and Algonquian linguistics to describe certain elem ...

''mide'' can be translated as "mystery," "mysterious," "spiritual," "sanctified," "sacred," or "ceremonial", depending on the context of its use. The derived verb

A verb () is a word ( part of speech) that in syntax generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual descr ...

''midewi'', thus means "be in/of ''mide''." The derived noun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, ...

''midewiwin'' then means "state of being in ''midewi''." Often ''mide'' is translated into English as "medicine" (thus the term ''midewinini'' "medicine-man") though ''mide'' conveys the idea of a spiritual medicine, opposed to ''mashkiki'' that conveys the idea of a physical medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

. A practitioner of Midewiwin is called a ''midew'', which can also be rendered as ''mide'o''... both forms of the word derived from the verb ''midewi'', or as a ''medewid'', a gerund form of ''midewi''. Specifically, a male practitioner is called a ''midewinini'' ("''midew'' man") and a female practitioner a ''midewikwe'' ("''midew'' woman").

Due to the body-part medial ''de meaning "heart" in the Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawa ...

language, "Midewiwin" is sometimes translated as "The Way of the Heart."Benton Banai Blessing shares a definition he received from Thomas Shingobe, a "Mida" (a Midewiwin person) of the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation in 1969, who told him that "the only thing that would be acceptable in any way as an interpretation of 'Mide' would be 'Spiritual Mystery'." Fluent speakers of Anishinaabemowin often caution that there are many words and concepts that have no direct translation to English.

Origins

According to historian Michael Angel, the Midewin is a "flexible, tenacious tradition that provided an institutional setting for the teaching of the world view (religious beliefs) of the Ojibwa people". Commonly among theAnishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawa ...

g, Midewin is ascribed to Wenaboozho (Onaniboozh) as its founder. However, among the Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

s, Midewiwin is ascribed to Mateguas, who bestowed the Midewiwin upon his death to comfort his grieving brother Gluskab, who is still alive. Walter James Hoffman

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born ...

recorded that according to the Mille Lacs Indians

The Mille Lacs Indians (Ojibwe: ''Misi-zaaga'iganiwininiwag''), also known as the Mille Lacs and Snake River Band of Chippewa, are a Band of Indians formed from the unification of the Mille Lacs Band of Mississippi Chippewa (Ojibwe) with the Mille ...

chief ''Bayezhig'' ("Lone One"), Midewiwin has its origin as:

:"In the beginning, Midemanidoo (Gichimanidoo) made the ''midemanidoowag''. He first created two men, and two women; but they had no power of thought or reason. Then ''Midemanidoo (Gichimanodoo)'' made them rational beings. He took them in his hands so that they should multiply; he paired them, and from this sprung the Anishinaabe. When there were people he placed them upon the earth, but he soon observed that they were subject to sickness, misery, and death, and that unless he provided them with the Sacred Medicine they would soon become extinct.

:"Between the position occupied by ''Gichi Manidoo'' and the earth were four lesser ''manidoog'' with whom ''Gichi Manidoo'' decided to commune, and to impart to them the mysteries by which the ''Anishinaabeg'' could be benefited. So he first spoke to a ''manidoo'' and told him all he had to say, who in turn communicated the same information to the next, and he in turn to next, who also communed with the next. They all met in council, and determined to call in the four wind ''manidoog''. After consulting as to what would be best for the comfort and welfare of the Anishinaabeg, these ''manidoog'' agreed to ask ''Gichi Manidoo'' to communicate the Mystery of the Sacred Medicine to the people.

:"''Gichi Manidoo'' then went to the Sun Spirit and asked him to go to the earth and instruct the people as had been decided upon by the council. The Sun Spirit, in the form of a little boy, went to the earth and lived with a woman who had a little boy of her own.

:"This family went away in the autumn to hunt, and during the winter this woman’s son died. The parents were so much distressed that they decided to return to the village and bury the body there; so they made preparations to return, and as they traveled along, they would each evening erect several poles upon which the body was placed to prevent the wild beasts from devouring it. When the dead boy was thus hanging upon the poles, the adopted child—who was the Sun Spirit—would play about the camp and amuse himself, and finally told his adopted father he pitied him, and his mother, for their sorrow. The adopted son said he could bring his dead brother to life, whereupon the parents expressed great surprise and desired to know how that could be accomplished.

:"The adopted boy then had the party hasten to the village, when he said, “Get the women to make a ''wiigiwaam'' of bark, put the dead boy in a covering of ''wiigwaas'' and place the body on the ground in the middle of the ''wiigiwaam''.” On the next morning after this had been done, the family and friends went into this lodge and seated themselves around the corpse.

:"When they had all been sitting quietly for some time, they saw through the doorway the approach of a bear, which gradually came towards the ''wiigiwaam'', entered it, and placed itself before the dead body and said, “ho, ho, ho, ho,” when he passed around it towards the left side, with a trembling motion, and as he did so, the body began quivering, and the quivering increased as the bear continued until he had passed around four times, when the body came to life again and stood up. Then the bear called to the father, who was sitting in the distant right-hand corner of the ''wiigiwaam'', and addressed to him the following words:

::

::

::

::

::

:"The little bear boy was the one who did this. He then remained among the Anishinaabeg and taught them the mysteries of the ''Midewiwin''; and, after he had finished, he told his adopted father that as his mission had been fulfilled he was to return to his kindred ''manidoog'', for the Anishinaabeg would have no need to fear sickness as they now possessed the ''Midewiwin'' which would enable them to live. He also said that his spirit could bring a body to life but once, and he would now return to the sun from which they would feel his influence."

This event is called ''Gwiiwizens wedizhichigewinid''—Deeds of a Little-boy.

Associations

Tribal groups who have such societies include theAbenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

, Quiripi

Quiripi (pronounced , also known as Mattabesic, Quiripi-Unquachog, Quiripi-Naugatuck, and Wampano) was an Algonquian languages, Algonquian language formerly spoken by the indigenous people of Gold Coast (Connecticut), southwestern Connecticut and ...

, Nipmuc

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian language. Their historic territory Nippenet, "the freshwater pond place," is in central Massachusetts and nearby part ...

, Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. ...

, Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawa ...

( Algonquin, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They h ...

and Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

), Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

, Meskwaki

The Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquaki), also known by the European exonyms Fox Indians or the Fox, are a Native American people. They have been closely linked to the Sauk people of the same language family. In the Meskwaki language, th ...

, Sauk, Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

and the Ho-Chunk

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Hoocągra or Winnebago (referred to as ''Hotúŋe'' in the neighboring indigenous Iowa-Otoe language), are a Siouan-speaking Native American people whose historic territory includes parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iow ...

. These indigenous peoples of Turtle Island pass along wiigwaasabak

''Wiigwaasabak'' (in Anishinaabe syllabics: , plural: ''wiigwaasabakoon'' ) are birch bark scrolls, on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people of North America wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes, also known as a "written language." ...

(birch bark scrolls), teachings, and have degrees of initiations and ceremonies. They are often associated with the Seven Fires Society, and other aboriginal groups or organizations. The Miigis shell, or cowry shell, is used in some ceremonies, along with bundles, sacred items, etc. There are many oral teachings, symbols, stories, history, and wisdom passed along and preserved from one generation to the next by these groups.

Whiteshell Provincial Park (Manitoba) is named after the whiteshell

Whiteshells (also known as Cowrie shells or Sacred ''Miigis'' Shells) were used by aboriginal peoples around the world, but the words "whiteshell" and "''Miigis'' Shell" specifically refers to shells used by Ojibway peoples in their Midewiwin cerem ...

(cowry) used in Midewiwin ceremonies. This park contains some petroform

Petroforms, also known as boulder outlines or boulder mosaics, are human-made shapes and patterns made by lining up large rocks on the open ground, often on quite level areas. Petroforms in North America were originally made by various Native A ...

s that are over 1000 years old, or possibly older, and therefore may predate some aboriginal groups that came later to the area. The Midew society is commemorated in the name of the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie (Illinois).

Degrees

The Mide practitioners are initiated and ranked by "degrees." Much like the apprentice system,masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

degrees, or an academic degree

An academic degree is a qualification awarded to students upon successful completion of a course of study in higher education, usually at a college or university. These institutions commonly offer degrees at various levels, usually including und ...

program, a practitioner cannot advance to the next higher degree until completing the required tasks and gain the full knowledge of that degree's requirements. Only after successful completion may a candidate be considered for advancement into the next higher degree.

Extended Fourth

The accounts regarding the extended Fourth Degrees vary from region to region. All Midewiwin groups claim the extended Fourth Degrees are specialized forms of the Fourth Degree. Depending on the region, these extended Fourth Degree Midew can be called "Fifth Degree" up to "Ninth Degree." In parallel, if the Fourth Degree Midew is to adoctorate degree

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

, the Extended Fourth Degree Midew is to a post-doctorate degree

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

. The Jiisakiwinini is widely referred to by Elders as the "highest" degree of all the medicine practitioners in the Mide, as it is spiritual medicine as opposed to physical/plant based medicine.

Medicine lodge

''Midewigaan''

The ''midewigaan'' ("''mide'' lodge"), also known as ''mide-wiigiwaam'' ("''mide''wigwam

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup' ...

") when small or ''midewigamig'' ("''mide'' structure") when large, is known in English as the "Grand Medicine Lodge" and is usually built in an open grove or clearing. A ''midewigaan'' is a domed structure with the proportion of 1 unit in width by 4 units in length. Though Hoffman records these domed oval structures measuring about 20 feet in width by 80 feet in length, the structures are sized to accommodate the number of invited participants, thus many ''midewigaan'' for small ''mide'' communities in the early 21st century are as small as 6 feet in width and 24 feet in length and larger in those communities with more ''mide'' participants. The walls of the smaller ''mide-wiigiwaam'' consist of poles and saplings from 8 to 10 feet high, firmly planted in the ground, wattled with short branches and twigs with leaves. In communities with significantly large ''mide'' participants (usually of 100 people or more participants), the ''midewigamig'' becomes a formal and permanent ceremonial building that retains the dimensions of the smaller ''mide-wiigiwaam''; a ''midewigamig'' might not necessarily be a domed structure, but typically may have vaulted ceilings.

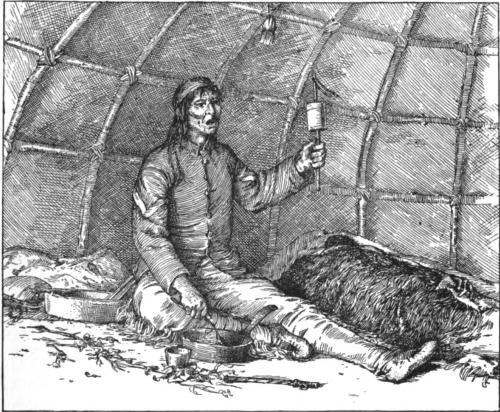

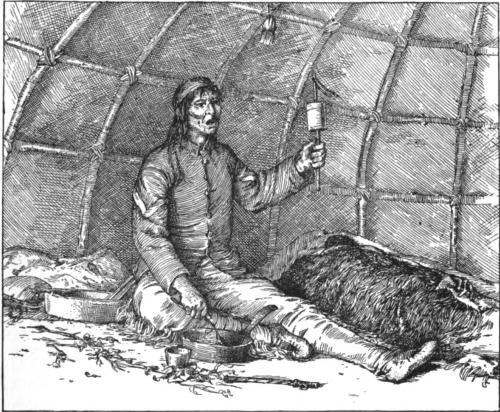

''Jiisakiiwigaan''

Design of the ''jiisakiiwigaan'' ("'juggler's lodge" or "Shaking Tent" or traditionally "shaking wigwam") is similar in construction as that of the ''mide-wiigiwaam''. Unlike a ''mide-wiigiwaam'' that is an oval domed structure, the ''jiisakiiwigaan'' is a round high-domed structure of typically 3 feet in diameter and 6 feet in height, and large enough to hold two to four people.Ceremonies

Annual and seasonal ceremonies

*''Aabita-biboon'' (Midwinter Ceremony) *''Animoosh'' (hite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro

HiteJinro Co., Ltd. (; ) is a South Korean multinational drink, brewing and distiller company, founded in 1924. It is the world's leading producer of soju, accounting for more than half of that beverage' ...

Dog Ceremony)

*''Jiibay-inaakewin'' or ''Jiibenaakewin'' (Feast of the Dead)

*''Gaagaagiinh'' or ''Gaagaagishiinh'' (Raven Festival)

*''Zaazaagiwichigan'' (Painted Pole Festival)

*''Mawineziwin'' ("War emembranceDance")

*''Wiikwandiwin'' ( easonalCeremonial Feast)—performed four times per year, once per season. The ''Wiikwandiwin'' is begun with a review of the past events, hope for a good future, a prayer and then the smoking of the pipe carried out by the heads of the doodem. These ceremonies are held in mid-winter and mid-summer in order to bring together peoples various medicines and combine their healing powers for revitalization. Each ''Wiikwandiwin'' is a celebration to give thanks, show happiness and respect to ''Gichi-manidoo''. It is customary to share the first kill of the season during the ''Wiikwandiwin''. This would show ''Gichi-manidoo'' thanks and also ask for a blessing for the coming hunt, harvest and season.

Rites of passage

*''Nitaawigiwin'' (Birth rites)—ceremony in which a newborn'sumbilical cord

In placental mammals, the umbilical cord (also called the navel string, birth cord or ''funiculus umbilicalis'') is a conduit between the developing embryo or fetus and the placenta. During prenatal development, the umbilical cord is physiologi ...

is cut and retained

*''Waawiindaasowin'' (Naming rites)—ceremony in which a name-giver presents a name to a child

*''Oshki-nitaagewin'' (First-kill rites)—ceremony in which a child's first successful hunt is celebrated

*''Makadekewin'' (Puberty fast rites)

*''Wiidigendiwin'' (Marriage rites)—ceremony in which a couple is joined into a single household

*''Bagidinigewin'' (Death rites)—wake, funeral and funerary feast

Miscellaneous ceremonies

*''Jiisakiiwin'' (Shaking tent)—ceremony conducted by a Shaking-tent seer (''jaasakiid''; a male ''jaasakiid'' known as a ''jiisakiiwinini'' or a female ''jaasakiid'' known as a ''jiisakiiwikwe''), often called a "Juggler" in English, who would enter the tent to conjure spirits and speak beyond this world. *''Bagisewin'' (Present)—custom at the end of a wedding ceremony in which the bride presents wood at the groom's feet as a wedding present. *''Ishkwaandem-wiikwandiwin'' (Entry-way Feast)—A ceremony performed by women who took a piece of wood out to the bushes to offer it to ''Gichi-manidoo'', and brought something back as well. This ceremony represents the woman as Mother Earth whom asked for blessing from ''Gichi-manidoo'' so that the home would be safe and warm.Teaching objects

Teaching scrolls

Called ''wiigwaasabakoon'' in theOjibwe language

Ojibwe , also known as Ojibwa , Ojibway, Otchipwe,R. R. Bishop Baraga, 1878''A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language''/ref> Ojibwemowin, or Anishinaabemowin, is an indigenous language of North America of the Algonquian la ...

, birch bark scrolls were used to pass on knowledge between generations. When used specifically for Midewiwin ceremonial use, these ''wiigwaasabakoon'' used as teaching scrolls were called ''Mide-wiigwaas'' ("Medicine birch ark scroll). Early accounts of the Mide from books written in the 1800s describe a group of elders that protected the birch bark scrolls in hidden locations. They recopied the scrolls if any were badly damaged, and they preserved them underground. These scrolls were described as very sacred and the interpretations of the scrolls were not easily given away. The historical areas of the Ojibwe were recorded, and stretched from the east coast all the way to the prairies by way of lake and river routes. Some of the first maps of rivers and lakes were made by the Ojibwe and written on birch bark.

"The Teachings of the Midewiwin were scratched on birch bark scrolls and were shown to the young men upon entrance into the society. Although these were crude pictographs representing the ceremonies, they show us that the Ojibwa were advanced in the development of picture 'writing.' Some of them were painted on bark. One large birch bark roll was 'known to have been used in the Midewiwin at Mille Lacs for five generations and perhaps many generations before', and two others, found in a seemingly deliberate hiding place in the Head-of-the-Lakes region of Ontario,Kidd, Kenneth E. "Birch-bark Scrolls in Archaeological Contexts", in ''American Antiquity'', Vol. 30 No. 4 (1965) p480. were carbon-dated to about 1560 CE +/-70.Rajnovich, Grace "Reading Rock Art: Interpreting the Indian Rock Paintings of the Canadian Shield". Dundurn Press Ltd. (1994) The author of the original report on these hidden scrolls advised: "Indians of this region occasionally deposited such artifacts in out-of-the-way places in the woods, either by burying them or by secreting them in caves. The period or periods at which this was done is far from clear. But in any event, archaeologists should be aware of the custom and not overlook the possibility of their discovery."

Teaching stones

Teaching stones known in Ojibwe as either ''Gikinoo'amaagewaabik'' or ''Gikinoo'amaage-asin'' can be eitherpetroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s or petroform

Petroforms, also known as boulder outlines or boulder mosaics, are human-made shapes and patterns made by lining up large rocks on the open ground, often on quite level areas. Petroforms in North America were originally made by various Native A ...

.

Seven prophetical ages

The seven fires prophecy was originally taught among the practitioners of ''Midewiwin''. Each fire represents a prophetical age, marking phases or epochs of Turtle Island. It represents key spiritual teachings for North America, and suggests that the different colors and traditions of humans can come together on a basis of respect. The Algonquins are the keepers of the seven fires prophecy ''wampum

Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of Native Americans. It includes white shell beads hand-fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell and white and purple beads made from the quahog or Western Nor ...

''.

See also

* Abenaki mythology * Anishinaabe traditional beliefs *Animism

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning ' breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things— animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather syst ...

* Hopewell tradition

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from ...

* Adena culture

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 500 BCE to 100 CE, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing ...

* Fort Ancient

* The red road

* Tengrism

Tengrism (also known as Tengriism, Tengerism, or Tengrianism) is an ethnic and old state Turko- Mongolic religion originating in the Eurasian steppes, based on folk shamanism, animism and generally centered around the titular sky god Tengri. ...

* Wabunowin

* Walam Olum

* Seven fires prophecy

Seven fires prophecy is an Anishinaabe prophecy that marks phases, or epochs, in the life of the people on Turtle Island, the original name given by the indigenous peoples of the now North American continent. The seven fires of the prophecy repre ...

References

Sources

*Angel, Michael. ''Preserving the Sacred: Historical Perspectives on the Ojibwa Midewiwin.'' (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2002). *Bandow, James B. "White Dogs, Black Bears & Ghost Gamblers: Two Late Woodland Midewiwin Aspects from Ontario". IN ''Gathering Places in Algonquian Social Discourse''. Proceedings of the 40th Algonquian Conference, Karle Hele & J. Randolf Valentine (Editors). (SUNY Press, 2008 - Released 2012) *Barnouw, Victor. "A Chippewa Mide Priest's Description of the Medicine Dance" in ''Wisconsin Archeologist,'' 41(1960), pp. 77–97. *Battiste, Marie, ed. ''Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision'' (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2000). *Benton-Banai, Edward. ''The Mishomis Book - The Voice of the Ojibway''. (St. Paul: Red School House publishers, 1988). *Blessing, Fred K., Jr. ''The Ojibway Indians observed''. (Minnesota Archaeological Society, 1977). *Deleary, Nicholas. "The Midewiwin, an aboriginal spiritual institution. Symbols of continuity: a native studies culture-based perspective." Carleton University MA Thesis, M.A. 1990. *Densmore, Frances. ''Chippewa Customs''. (Reprint: Minnesota Historical Press, 1979). *Dewdney, Selwyn Hanington. ''The Sacred Scrolls of the Southern Ojibway''. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1975). *Gross, Lawrence W. "Bimaadiziwin, or the 'Good Life,' as a Unifying Concept of Anishinaabe Religion" in ''American Indian Culture and Research Journal'', 26(2002):1, pp. 15–32. *Hirschfelder, Arlene B. and Paulette Molin, eds. ''The Encyclopedia of Native American Religions''. (New York: Facts of File, 1992)Hoffman, Walter James. "The Midewiwin, or 'Grand Medicine Society', of the Ojibwa" in ''Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Bureau of Ethnology Report'', v. 7, pp. 149-299. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891).

* Johnston, Basil. "The Society of Medicine\''Midewewin''" in ''Ojibway Ceremonies'', pp. 93–112. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990). *Landes, Ruth. ''Ojibwa Religion and the Midéwiwin''. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968). *Roufs, Tim. ''When Everybody Called Me Gah-bay-bi-nayss: "Forever-Flying-Bird".'' An Ethnographic Biography of Paul Peter Buffalo. (Duluth: University of Minnesota, 2007).

Chapter 30: Midewiwin: Grand Medicine

** ttp://www.d.umn.edu/cla/faculty/troufs/Buffalo/PB33.html Chapter 33: Medicine Men / Medicine Women*Vecsey, Christopher. ''Traditional Ojibwa Religion and its Historical Changes''. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983). *Warren, William W. ''History of the Ojibway People''. (1851) {{Anishinaabe Native American religion Traditional healthcare occupations