Mental accounting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mental accounting (or psychological accounting) attempts to describe the process whereby people code, categorize and evaluate

Mental accounting (or psychological accounting) attempts to describe the process whereby people code, categorize and evaluate

Clearly, the way in which we perceive two outcomes (how we account for them), can influence how positively (or negatively) we view them.

Another very important concept used to understand mental accounting is that of modified utility function. There are two values attached to any transaction - acquisition value and transaction value. ''Acquisition value'' is the money that one is ready to part with for physically acquiring some good. ''Transaction value'' is the value one attaches to having a good deal. If the price that one is paying is equal to the mental reference price for the good, the transaction value is zero. If the price is lower than the reference price, the transaction utility is positive. Total utility received from a transaction, then, is the sum of acquisition utility and transaction utility.

Clearly, the way in which we perceive two outcomes (how we account for them), can influence how positively (or negatively) we view them.

Another very important concept used to understand mental accounting is that of modified utility function. There are two values attached to any transaction - acquisition value and transaction value. ''Acquisition value'' is the money that one is ready to part with for physically acquiring some good. ''Transaction value'' is the value one attaches to having a good deal. If the price that one is paying is equal to the mental reference price for the good, the transaction value is zero. If the price is lower than the reference price, the transaction utility is positive. Total utility received from a transaction, then, is the sum of acquisition utility and transaction utility.

Mental accounting (or psychological accounting) attempts to describe the process whereby people code, categorize and evaluate

Mental accounting (or psychological accounting) attempts to describe the process whereby people code, categorize and evaluate economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

outcomes. The concept was first named by Richard Thaler

Richard H. Thaler (; born September 12, 1945) is an American economist and the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. In 2015, Thaler was p ...

. Mental accounting deals with the budgeting and categorization of expenditures. People budget money into mental accounts for expenses (e.g., saving for a home) or expense categories (e.g., gas money, clothing, utilities). Mental accounts are believed to act as a self-control strategy. People are presumed to make mental accounts as a way to manage and keep track of their spending and resources. People also are assumed to make mental accounts to facilitate savings for larger purposes (e.g., a home or college tuition). Like many other cognitive processes, it can prompt biases and systematic departures from rational, value-maximizing behavior, and its implications are quite robust. Understanding the flaws and inefficiencies of mental accounting is essential to making good decisions and reducing human error

Human error refers to something having been done that was " not intended by the actor; not desired by a set of rules or an external observer; or that led the task or system outside its acceptable limits".Senders, J.W. and Moray, N.P. (1991) Human ...

.

As Thaler puts it, “All organizations, from General Motors down to single person households, have explicit and/or implicit accounting systems. The accounting system often influences decisions in unexpected ways”. We often see consumer behavior deviate from the standard economic prediction; mental accounting is a framework that seeks to further explain consumer behavior, and describe when consumers might violate standard economic principles. Particularly, individual expenses will usually not be considered in conjunction with the present value of one’s total wealth; they will be instead considered in the context of two accounts: the current budgetary period (this could be a monthly process due to bills, or yearly due to an annual income), and the category of expense. People can even have multiple mental accounts for the same kind of resource. A person may use different monthly budgets for grocery shopping and eating out at restaurants, for example, and constrain one kind of purchase when its budget has run out while not constraining the other kind of purchase, even though both expenditures draw on the same fungible resource (income).

One detailed application of mental accounting, the behavioral life cycle hypothesis , posits that people mentally frame assets as belonging to either current income, current wealth or future income and this has implications for their behavior as the accounts are largely non-fungible and marginal propensity to consume

In economics, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is a metric that quantifies induced consumption, the concept that the increase in personal consumer spending ( consumption) occurs with an increase in disposable income (income after taxes and ...

out of each account is different.

Utility, value and transaction

In mental accounting theory, '' framing'' means that the way a person subjectively frames a transaction in their mind will determine theutility

As a topic of economics, utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness as part of the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosoph ...

they receive or expect. This concept is similarly used in prospect theory

Prospect theory is a theory of behavioral economics and behavioral finance that was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory was cited in the decision to award Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

Based ...

, and many mental accounting theorists adopt that theory as the value function The value function of an optimization problem gives the value attained by the objective function at a solution, while only depending on the parameters of the problem. In a controlled dynamical system, the value function represents the optimal payof ...

in their analysis. It is important to note that the value function is concave for gains (implying an aversion to risk) and convex for losses (implying a risk-seeking attitude). This can influence the way people evaluate transactions.

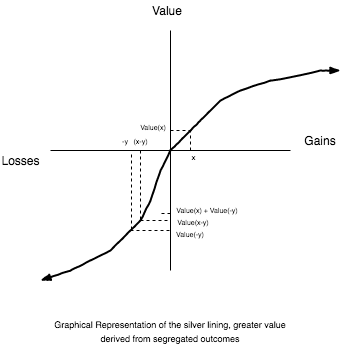

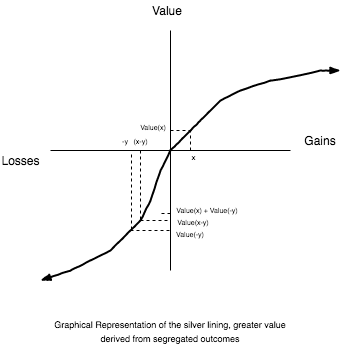

Given this framework, how do people interpret, or ‘account for’, multiple transactions/outcomes, of the format ? They can either view the outcomes jointly, and receive , in which case the outcomes are integrated, or, in which case we say that the outcomes are segregated. Due to the nature of our value function’s different slopes for gains and losses, our utility is maximized in different ways, depending on how we code the four kinds of transactions and (as gains or as losses):

1) Multiple gains: and are both considered gains. Here, we see that . Thus, we want to segregate multiple gains.

2) Multiple losses: and are both considered losses. Here, we see that . We want to integrate multiple losses.

3) Mixed gain: one of and is a gain and one is a loss, however the gain is the larger of the two. In this case, . Utility is maximized when we integrate a mixed gain.

4) Mixed loss: again, one of and is a gain and one is a loss, however the loss is now ''significantly'' larger than the gain. In this case, . Clearly, we don't want to integrate a mixed loss when the less is significantly larger than the gain. This is often referred to as a "silver lining", a reference to the folk maxim "every cloud has a silver lining". When the loss is just barely larger than the gain, integration may be preferred.

Clearly, the way in which we perceive two outcomes (how we account for them), can influence how positively (or negatively) we view them.

Another very important concept used to understand mental accounting is that of modified utility function. There are two values attached to any transaction - acquisition value and transaction value. ''Acquisition value'' is the money that one is ready to part with for physically acquiring some good. ''Transaction value'' is the value one attaches to having a good deal. If the price that one is paying is equal to the mental reference price for the good, the transaction value is zero. If the price is lower than the reference price, the transaction utility is positive. Total utility received from a transaction, then, is the sum of acquisition utility and transaction utility.

Clearly, the way in which we perceive two outcomes (how we account for them), can influence how positively (or negatively) we view them.

Another very important concept used to understand mental accounting is that of modified utility function. There are two values attached to any transaction - acquisition value and transaction value. ''Acquisition value'' is the money that one is ready to part with for physically acquiring some good. ''Transaction value'' is the value one attaches to having a good deal. If the price that one is paying is equal to the mental reference price for the good, the transaction value is zero. If the price is lower than the reference price, the transaction utility is positive. Total utility received from a transaction, then, is the sum of acquisition utility and transaction utility.

Pain of Paying

A more proximal psychological mechanism through which mental accounting influences spending is through its influence on the pain of paying that is associated with spending money from a mental account. Pain of paying is a negative affective response associated with a financial loss. Prototypical examples are the unpleasant feeling that one experiences when watching the fare increase on a taximeter or at the gas pump. When considering an expense, consumers appear to compare the cost of the expense to the size of an account that it would deplete (e.g., numerator vs. denominator). A $30 t-shirt, for example, would be a subjectively larger expense when drawn from $50 in one's wallet than $500 in one's checking account. The larger the fraction, the more pain of paying the purchase appears to generate and the less likely consumers are to then exchange money for the good. Other evidence of the relation between pain of paying and spending include the lower debt held by consumers who report experiencing a higher pain of paying for the same goods and services than consumers who report experiencing less pain of paying.Practical implications

Psychology

Mental accounting is subject to manylogical fallacies In philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur (; Latin for " tdoes not follow") is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic syst ...

and cognitive biases

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, m ...

, which hold many implications such as overspending.

Credit cards and cash payments

Another example of mental accounting is the greater willingness to pay for goods when using credit cards than cash. If one uses a credit card to pay for tickets to a sporting event, they will tend to be willing to pay more than if they made their bid with cash. This phenomenon is also related to transaction decoupling, the separation of when a good is acquired and when it is actually paid for. Swiping a credit card prolongs the payment to a later date (when we pay our monthly bill) and it adds it to a large existing sum (our bill to that point). This delay causes the payment to stick in our memory less clearly and saliently. Furthermore, the payment is no longer perceived in isolation; rather, it is seen as a (relatively) small increase of an already large credit card bill. For example, it might be a change from $120 to $125, instead of a regular, out-of-pocket $5 cost. And as we can see from our value function, this ''V(-$125) – V(-$120)'' is smaller than ''V(-$5)''. This phenomenon is referred to as payment decoupling.Marketing

Mental accounting is useful for marketers, in particular, as it makes useful predictions for how consumers will respond to different ways of presenting losses and gains. People respond more positively to incentives and costs when gains are segregated, losses are integrated, marketers segregate net losses (the silver lining principle), and integrate net gains. Automotive dealers, for example, benefit from these principles when they bundle optional features into a single price but segregate each feature included in the bundle (e.g., heated seats, heated steering wheel, mirror defrosters). Cellular phone companies can use principles of mental accounting when deciding how much to charge consumers for a new smartphone and to give them for their trade-in. When the cost of the phone is large and the value of the phone to be traded in is low, it is better to charge consumers a slightly higher price for the phone and return that money to them as a higher value on their trade in. Conversely, when the cost of the phone and the value of the trade-in are more comparable, because consumers are loss averse, it is better to charge them less for the new phone and offer them less for the trade-in.Public policy

Mental accounting can also be utilized inpublic economics

Public economics ''(or economics of the public sector)'' is the study of government policy through the lens of economic efficiency and equity. Public economics builds on the theory of welfare economics and is ultimately used as a tool to improve s ...

and public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public p ...

. Policy-makers and public economists would do well to consider mental accounting when crafting public systems, trying to understand and identify market failures, redistribute wealth or resources in a fair way, reduce the saliency of sunk cost

In economics and business decision-making, a sunk cost (also known as retrospective cost) is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered. Sunk costs are contrasted with '' prospective costs'', which are future costs that may be ...

s, limiting or eliminating the Free-rider problem

In the social sciences, the free-rider problem is a type of market failure that occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods (such as public roads or public library), or services of a communal nature do not pay for them or under-p ...

, or even just when delivering bundles of multiple goods or services to taxpayers. Inherently, the way that people (and therefore taxpayer and voters) perceive decisions and outcomes will be influenced by their process of mental accounting. If policy-makers consider the implications of how people mentally book-keep their decisions, they should be able to frame and construct public policy that results in better decisions for health, wealth, and happiness.

A good example of the importance of considering mental accounting while crafting public policy is demonstrated by authors Justine Hastings and Jesse Shapiro in their analysis of the SNAP ( Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program). They "argue that these findings are not consistent with households treating SNAP funds as fungible

In economics, fungibility is the property of a good or a commodity whose individual units are essentially interchangeable, and each of whose parts is indistinguishable from any other part. Fungible tokens can be exchanged or replaced; for exam ...

with non-SNAP funds, and we support this claim with formal tests of fungibility that allow different households to have different consumption functions" Put differently, their data supports Thaler's (and the concept of mental accounting's) claim that the principle of fungibility is often violated in practice. Furthermore, they find SNAP to be very effective, calculating a marginal propensity to consume

In economics, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is a metric that quantifies induced consumption, the concept that the increase in personal consumer spending ( consumption) occurs with an increase in disposable income (income after taxes and ...

SNAP-eligible food (MPCF) out of benefits received by SNAP of 0.5 to 0.6. This is much higher than the MPCF out of cash transfers, which is usually around 0.1. Clearly, mental accounting is leveraged by SNAP to make it a more effective policy.

Authors Emmanuel Farhi and Xavier Gabaix examine the implications of mental accounting for taxation in their paper: ''Optimal Taxation with Behavioral Insights''. The authors main goal is to revisit the three pillars of optimal taxation, and add a behavioral twist to them which tries to incorporate mental accounting (as well as misperceptions and internalities). They reach a number of novel economic insights, showing how to incorporate nudges in the optimal taxation frameworks, and challenging the Diamond-Mirrlees productive efficiency result and the Atkinson-Stiglitz uniform commodity taxation proposition, finding they are more likely to fail with behavioral agents.

In the paper ''Public vs. Private Mental Accounts: Experimental Evidence from Savings Groups in Colombia'', Luz Magdalena Salas shows how mental accounting can be exploited to help nudge people towards saving more. In the randomized control trial that she runs, we see that labeling savings goals in different ways can lead to different levels of success in achieving savings goals. Further, the power of this labeling effect differs based on the saving success that people were having to begin with.

Mental accounting plays a powerful role in our decision-making processes. It is important for public policy experts, researchers, and policy-makers continue to explore the ways that it can be utilized to benefit public welfare.

See also

* Decision making * Behavioral economics * Framing effect (psychology) *Micropayment

A micropayment is a financial transaction involving a very small sum of money and usually one that occurs online. A number of micropayment systems were proposed and developed in the mid-to-late 1990s, all of which were ultimately unsuccessful. A s ...

* Preference

* Psychological pricing

* Transaction cost

In economics and related disciplines, a transaction cost is a cost in making any economic trade when participating in a market. Oliver E. Williamson defines transaction costs as the costs of running an economic system of companies, and unlike pro ...

* Sunk cost

In economics and business decision-making, a sunk cost (also known as retrospective cost) is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered. Sunk costs are contrasted with '' prospective costs'', which are future costs that may be ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * {{refend Behavioral finance