Menahem Mendel Beilis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of

Samuel, Maurice, Alfred A. Knopf, 1966. Beilis had already been in prison for over a year when a delegation led by a military officer came to his cell. In what might have been a ploy to get Beilis to incriminate himself or other Jews, the officer informed Beilis that he would soon be freed due to a manifesto pardoning all '' katorzhniks'' (convicts at hard labor) on the tercentenary jubilee of the reign of the

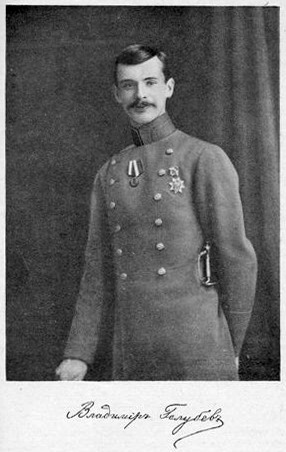

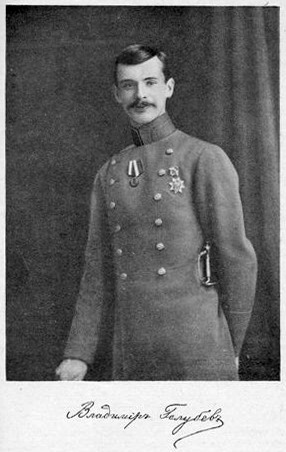

During the pre-trial period in 1911–1912 the investigation was conducted by Nikolay Krasovsky (Николай Александрович Красовский), the foremost investigator of the Kiev Police Department. Krasovsky forsook any prospect of promotion and continued his investigation in spite of resistance and sabotage from the circles interested in railroading Beilis; he eventually refused to participate in the alleged falsification of the case and was fired.

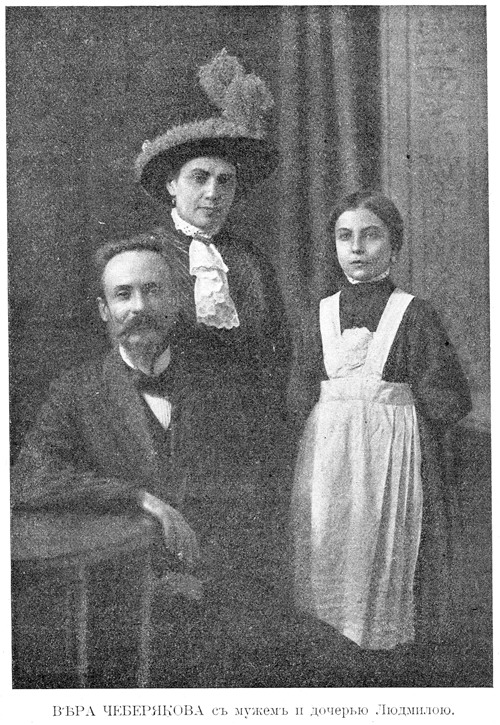

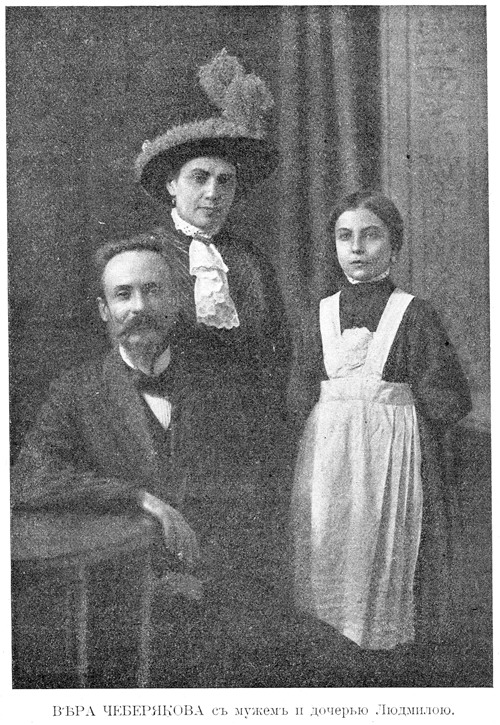

Krasovsky continued his investigation privately, assisted by his former colleagues from the Kiev Police Department. They eventually were able to determine the actual killers of Yushchinskyi: professional criminals with the names Rudzinsky, Singayevsky, Latyshev, and Vera Cheberyak, whose son Yevgeny was a friend of Yushchinskyi’s.

On 30–31 May 1912, reports were published in Kiev's newspapers. Immediately after this, Krasovsky was arrested on charges of official misuse committed in 1913 but acquitted by a court.

The Beilis trial took place in Kiev from September 25 through October 28, 1913. The prosecution was composed of the government's best lawyers. Professor Sikorsky of

During the pre-trial period in 1911–1912 the investigation was conducted by Nikolay Krasovsky (Николай Александрович Красовский), the foremost investigator of the Kiev Police Department. Krasovsky forsook any prospect of promotion and continued his investigation in spite of resistance and sabotage from the circles interested in railroading Beilis; he eventually refused to participate in the alleged falsification of the case and was fired.

Krasovsky continued his investigation privately, assisted by his former colleagues from the Kiev Police Department. They eventually were able to determine the actual killers of Yushchinskyi: professional criminals with the names Rudzinsky, Singayevsky, Latyshev, and Vera Cheberyak, whose son Yevgeny was a friend of Yushchinskyi’s.

On 30–31 May 1912, reports were published in Kiev's newspapers. Immediately after this, Krasovsky was arrested on charges of official misuse committed in 1913 but acquitted by a court.

The Beilis trial took place in Kiev from September 25 through October 28, 1913. The prosecution was composed of the government's best lawyers. Professor Sikorsky of

Beilis died unexpectedly at a hotel in

Beilis died unexpectedly at a hotel in

Chabad article on Beilis case

(Beyond the Pale – friends-partners.org) *

*

later issued as a pamphlet *

an

by

Stenographic report from the trial

Volumes 1–3 *

Бейлис, Менахем Мендель

in Shorter Jewish Encyclopedia, Jerusalem. 1976–2005 *

Beilis affair: truth and myth

by Feliks Levitas, Mikhail Frenkel (''Jewish Observer'', Jewish Confederation of Ukraine) April 12, 2006 {{DEFAULTSORT:Beilis, Menahem Mendel 1874 births 1934 deaths People from Kyiv People from Kiev Governorate Ukrainian Jews Antisemitic attacks and incidents in Europe Antisemitism in the Russian Empire Blood libel Jews and Judaism in the Russian Empire Trials in Ukraine 1913 in Judaism Ukrainian emigrants to the United States

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of ritual murder

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in a notorious 1913 trial, known as the "Beilis trial" or the "Beilis affair". Although Beilis was eventually acquitted after a lengthy process, the legal process sparked international criticism of antisemitism in the Russian Empire.

Beilis's story was fictionalized in Bernard Malamud

Bernard Malamud (April 26, 1914 – March 18, 1986) was an American novelist and short story writer. Along with Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, and Philip Roth, he was one of the best known American Jewish authors of the 20th century. His baseba ...

's 1966 novel '' The Fixer'', which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published durin ...

and the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction

The National Book Award for Fiction is one of five annual National Book Awards, which recognize outstanding literary work by United States citizens. Since 1987 the awards have been administered and presented by the National Book Foundation, but ...

.

Background

Menahem Mendel Beilis was born into aHasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of conte ...

family, but was indifferent to religion, and worked regularly on the Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stori ...

and at least some of the holidays

A holiday is a day set aside by custom or by law on which normal activities, especially business or work including school, are suspended or reduced. Generally, holidays are intended to allow individuals to celebrate or commemorate an event or t ...

. In 1911, he was an ex-soldier and the father of five children, employed as a superintendent at the Zaitsev brick factory in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

.

Murder of Andriy Yushchinskyi

On March 12, 1911 (under the old Russian calendar), 13-year-old Andriy Yushchinskyi disappeared on his way to school. Eight days later, his mutilated body was discovered in a cave near the Zaitsev brick factory. Beilis was arrested on July 21, 1911, after a lamplighter testified that the boy had been kidnapped by a Jew. A report submitted to theTsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

by the judiciary regarded Beilis as the murderer of Yushchinskyi.

Beilis spent more than two years in prison awaiting trial. Meanwhile, an antisemitic campaign was launched in the Russian press against the Jewish community, with accusations of the ritual murder. Among those who wrote or spoke against false accusations of the Jews were Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

, Vladimir Korolenko

Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko (russian: Влади́мир Галактио́нович Короле́нко, ua, Володи́мир Галактіо́нович Короле́нко; 27 July 1853 – 25 December 1921) was a Ukrainian-born ...

, Alexander Blok

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok ( rus, Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Бло́к, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈblok, a=Ru-Alyeksandr Alyeksandrovich Blok.oga; 7 August 1921) was a Russian lyrical poet, writer, publ ...

, Alexander Kuprin

Aleksandr Ivanovich Kuprin (russian: link=no, Александр Иванович Куприн; – 25 August 1938) was a Russian writer best known for his novels ''The Duel'' (1905)Kuprin scholar Nicholas Luker, in his biography ''A ...

, Vladimir Vernadsky, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi and Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Co ...

.Blood Accusation: the Strange History of the Beiliss CaseSamuel, Maurice, Alfred A. Knopf, 1966. Beilis had already been in prison for over a year when a delegation led by a military officer came to his cell. In what might have been a ploy to get Beilis to incriminate himself or other Jews, the officer informed Beilis that he would soon be freed due to a manifesto pardoning all '' katorzhniks'' (convicts at hard labor) on the tercentenary jubilee of the reign of the

Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

. As related in his memoir, Beilis refused this overture:

:“That manifesto,” said I, “will be for ''katorzhniks'', not for me. I need no manifesto, I need a fair trial.”

:“If you will be ordered to be released, you’ll have to go.”

:“No – even if you open the doors of the prison, and threaten me with shooting, I shall not leave. I shall not go without a trial.”

This is one of many incidents from Beilis's memoir that Bernard Malamud

Bernard Malamud (April 26, 1914 – March 18, 1986) was an American novelist and short story writer. Along with Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, and Philip Roth, he was one of the best known American Jewish authors of the 20th century. His baseba ...

incorporated in his novel ''The Fixer''.

The trial

During the pre-trial period in 1911–1912 the investigation was conducted by Nikolay Krasovsky (Николай Александрович Красовский), the foremost investigator of the Kiev Police Department. Krasovsky forsook any prospect of promotion and continued his investigation in spite of resistance and sabotage from the circles interested in railroading Beilis; he eventually refused to participate in the alleged falsification of the case and was fired.

Krasovsky continued his investigation privately, assisted by his former colleagues from the Kiev Police Department. They eventually were able to determine the actual killers of Yushchinskyi: professional criminals with the names Rudzinsky, Singayevsky, Latyshev, and Vera Cheberyak, whose son Yevgeny was a friend of Yushchinskyi’s.

On 30–31 May 1912, reports were published in Kiev's newspapers. Immediately after this, Krasovsky was arrested on charges of official misuse committed in 1913 but acquitted by a court.

The Beilis trial took place in Kiev from September 25 through October 28, 1913. The prosecution was composed of the government's best lawyers. Professor Sikorsky of

During the pre-trial period in 1911–1912 the investigation was conducted by Nikolay Krasovsky (Николай Александрович Красовский), the foremost investigator of the Kiev Police Department. Krasovsky forsook any prospect of promotion and continued his investigation in spite of resistance and sabotage from the circles interested in railroading Beilis; he eventually refused to participate in the alleged falsification of the case and was fired.

Krasovsky continued his investigation privately, assisted by his former colleagues from the Kiev Police Department. They eventually were able to determine the actual killers of Yushchinskyi: professional criminals with the names Rudzinsky, Singayevsky, Latyshev, and Vera Cheberyak, whose son Yevgeny was a friend of Yushchinskyi’s.

On 30–31 May 1912, reports were published in Kiev's newspapers. Immediately after this, Krasovsky was arrested on charges of official misuse committed in 1913 but acquitted by a court.

The Beilis trial took place in Kiev from September 25 through October 28, 1913. The prosecution was composed of the government's best lawyers. Professor Sikorsky of Kiev State University

Kyiv University or Shevchenko University or officially the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv ( uk, Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка), colloquially known as KNU ...

(father of Igor Sikorsky

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky (russian: И́горь Ива́нович Сико́рский, p=ˈiɡərʲ ɪˈvanəvitʃ sʲɪˈkorskʲɪj, a=Ru-Igor Sikorsky.ogg, tr. ''Ígor' Ivánovich Sikórskiy''; May 25, 1889 – October 26, 1972)Fortie ...

), a medical psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the pre ...

, testified as an expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

for the prosecution that in his opinion it was a case of ritual murder

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

.

Beilis had a strong alibi that resulted from his habit of working on the Jewish Sabbath. Yushchinskyi was abducted on a Saturday morning, and Beilis was then at work, as confirmed by his Gentile co-workers in trial testimony. Receipt slips for a shipment of bricks, signed by Beilis that morning, were produced in evidence. The prosecution was forced to argue that Beilis could have ducked out for a few minutes, kidnapped Yushchinskyi, and then returned to work.

Internal police documents from 1912 subsequently revealed that the weakness of the case was known.

Prosecution expert

One prosecution witness, presented as a religious expert in Judaic rituals, was a LithuanianCatholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest, Justinas Pranaitis from Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

, well known for his antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

1892 work '' Talmud Unmasked''. Pranaitis testified that the murder of Yushchinskyi was a religious ritual, associating the murder of Yushchinskyi with the blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

, a legend believed by many Russians at the time. One police department official is quoted as saying:

:''The course of the trial will depend on how the ignorant jury will perceive arguments of priest Pranaitis, who is sure about the reality of ritual murders. I think, as a priest he is able to talk with peasants and to convince them. As a scientist, who defended a thesis about this question, he will give props to the court and prosecution, though nothing can be guessed in advance yet. I became acquainted with Pranaitis and am firmly convinced that he is the person who knows the problem, about which he will talk, in depth... Everything, then, will depend on which arguments priest Pranaitis will furnish, and he has them, and they're shattering for the Jewry.''

Pranaitis' credibility rapidly evaporated when the defense demonstrated his ignorance of some simple Talmudic concepts and definitions, such as hullin

Hullin or Chullin (lit. "Ordinary" or "Mundane") is the third tractate of the Mishnah in the Order of Kodashim and deals with the laws of ritual slaughter of animals and birds for meat in ordinary or non-consecrated use (as opposed to sacred use ...

, to the point where "many in the audience occasionally laughed out loud when he clearly became confused and couldn't even intelligibly answer some of the questions asked by my lawyer."''Scapegoat on Trial: The Story of Mendel Beilis – The Autobiography of Mendel Beilis the Defendant in the Notorious 1912 Blood Libel in Kiev'', Beilis, Mendel, Introd. & Ed. By Shari Schwartz, CIS, New York, 1992, A Tsarist secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

agent is quoted, reporting on Pranaitis' testimony, as saying:

:''Cross-examination of Pranaitis has weakened evidentiary value of his expert opinion, exposing lack of knowledge of texts, insufficient knowledge of Jewish literature. Because of amateurish knowledge and lack of resourcefulness, Pranaitis' expert opinion is of very low value. Professors Troitskij and Kokovtsev, who were interrogated today, gave conclusions which are exceptionally positive for the defence, praising doctrines of the Jewish religion, and not accepting even a possibility of a religious murder by Jews ... Vipper thinks that acquittal is possible.''

Defense

A Beilis Defense Committee advisor, a writer named Ben-Zion Katz, suggested countering Father Pranaitis with questions like "When did '' Baba Bathra'' live and what was her activity" which he described as the equivalent of asking an American "Who lived at theGettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a speech that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln delivered during the American Civil War at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the ...

?" There were enough Jews in the court for the resultant laughter to negate Pranatis' value to the prosecution.

Beilis was represented by the most able attorneys of the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, St. Petersburg, and Kiev bars: Vasily Maklakov

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov (Russian: Васи́лий Алексе́евич Маклако́в; , Moscow – July 15, 1957, Baden, Switzerland) was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and one ...

, Oscar Gruzenberg, N. Karabchevsky, A. Zarudny, and D. Grigorovitch-Barsky. Two prominent Russian professors, Troitsky and Kokovtzov, spoke on behalf of the defense in praise of Jewish values and exposed the falsehood of the accusations, while Aleksandr Glagolev, philosopher and professor of the Kiev Theological Academy

The Kiev Theological Academy (1819—1919) was one of the oldest higher educational institution of the Russian Orthodox Church, situated in Kyiv, then in the Russian Empire (now Kyiv, Ukraine). It was considered as the most senior one among simil ...

of the Orthodox Christian, affirmed that "the Law of Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

forbids spilling human blood and using any blood in general in food." The well-known and respected Rabbi of Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Rabbi Yaakov Mazeh, delivered a long, detailed speech quoting passages from the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

, the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

and many other books to conclusively debunk the testimony of the "experts" brought forth by the prosecution.

Case summary

The lamplighter on whose testimony the indictment of Beilis rested confessed that he had been confused by thesecret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

.

The prosecution's case was further undermined after it had spent a great deal of effort to link the 13 wounds which Professor Sikorsky had discovered on a part of the murdered boy's body with the importance of the number thirteen

Thirteen or 13 may refer to:

* 13 (number), the natural number following 12 and preceding 14

* One of the years 13 BC, AD 13, 1913, 2013

Music

* 13AD (band), an Indian classic and hard rock band

Albums

* ''13'' (Black Sabbath album), 2013

* ...

in "Jewish ritual," only to have it revealed later that there were actually 14 wounds on that part of the body.

The chief prosecutor A.I. Vipper made supposedly antisemitic statements in his closing address. There are conflicting accounts of the twelve Christian juror

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartial verdict (a finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Juries developed in England dur ...

s: seven were members of the notorious Union of the Russian People, part of the movement known as the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

. There was no representative of the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

in the jury. However, after deliberating for several hours, the jury acquitted Beilis.

After the trial

The Beilis trial was followed worldwide and the antisemitic policies of the Russian Empire were severely criticized. The Arabic newspaper '' Filastin'' published in Jaffa, Palestine, dealt with this trial in several articles. Its editor, Yousef El-Issa, published an editorial titled: "The Disgrace of the Twentieth Century". He wrote on 13 October 1913: The Beilis case was compared with the Leo Frank case, in which an American Jew, manager of a pencil factory inAtlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital city, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georgia, Fulton County, the mos ...

, was convicted of raping and murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan. Leo Frank was lynched after his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

After his acquittal, Beilis became an enormous hero and celebrity. One indication of the extent of his fame is the following quote: "Anyone wanting to see the major stars of New York’s Yiddish stage on Thanksgiving weekend in 1913 had three choices: ''Mendel Beilis'' at Jacob Adler’s Dewey Theater, ''Mendel Beilis'' at Boris Thomashefsky’s National Theater, or ''Mendel Beilis'' at David Kessler’s Second Avenue Theater.”

Due to his great fame and the adulation he received, Beilis could have become wealthy through commercial appearances and the like. Spurning all such offers, he and his family left Russia for a farm purchased by Baron Rothschild in Palestine, then a province of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

.

Beilis had difficulty making ends meet in Palestine, but for years he resisted leaving. When friends and well-wishers pleaded with him to go to America, he would respond: “Before, in Russia, when the word ‘Palestine’ conjured up a waste and barren land, even then I chose to come here in preference to other countries. How much more, then, would I insist on staying here, after I have come to love the land!”

United States

Finally, however, Beilis’s financial situation became too desperate. In 1921 he settled in theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

where in 1925 he self-published an account of his experiences titled ''The Story of My Sufferings''. Originally published in Yiddish (1925 and 1931 editions), the book was later translated into English (1926, 1992, and 2011 editions), and also Russian.

Beilis died unexpectedly at a hotel in

Beilis died unexpectedly at a hotel in Saratoga Springs, New York

Saratoga Springs is a city in Saratoga County, New York, United States. The population was 28,491 at the 2020 census. The name reflects the presence of mineral springs in the area, which has made Saratoga a popular resort destination for over ...

on July 7, 1934 and was buried two days later at the Mount Carmel Cemetery, Glendale, Queens, which is the burial place of Leo Frank and Sholem Aleichem

)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pereiaslav, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = New York City, U.S.

, occupation = Writer

, nationality =

, period =

, genre = Novels, sh ...

. Though Beilis’s fame had faded since the trial in 1913, it returned briefly at his death. His funeral was attended by over 4,000 people. The ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' noted that Beilis’s fellow Jews “always believed that his conduct n resisting all pressure to implicate himself or other Jewssaved his countrymen from a pogrom.” A history of the Eldridge Street Synagogue

The Eldridge Street Synagogue is a synagogue and National Historic Landmark in Chinatown, Manhattan, New York City. Built in 1887, it is one of the first synagogues erected in the United States by Eastern European Jews.

The Orthodox congre ...

, where Beilis's funeral was held, describes the scene at his funeral as follows: “The crowd could not be contained in the sanctuary. As many as a dozen policemen failed to establish order in the streets.”

Around six months before his death, Beilis was interviewed by the English-language '' Jewish Daily Bulletin''. Asked for “one outstanding impression” of the trial in Kiev, he paid a final tribute to the Russian Gentiles who had helped him to escape the blood libel, such as the detective (Nikolai Krasovsky) and the journalist Brazul-Brushkovsky: “There was real heroism, real sacrifice. They knew that by defending me their careers would be ruined, even their very lives would not be safe. But they persisted because they knew I was innocent.”

Controversy over depiction in ''The Fixer''

While Bernard Malamud's novel '' The Fixer'' is based on the life of Mendel Beilis, Malamud transformed Beilis’ character, and that of his wife, in ways that Beilis's descendants found degrading. The actual Mendel Beilis was, supposedly, “a dignified, respectful, well-liked, fairly religious family man with a faithful wife, Esther, and five children.” Malamud's protagonist Yakov Bok is “an angry, foul-mouthed, cuckolded, friendless, childless blasphemer.” When ''The Fixer'' was first published, Beilis’ son David Beilis wrote to Malamud, complaining both that Malamud had plagiarized from Beilis’ memoirs and that Malamud had debased the memories of Beilis and his wife through the characters of Yakov Bok and Bok's wife Raisl. Malamud wrote back, attempting to reassure David Beilis that ''The Fixer'' “makes no attempt to portray Mendel Beilis or his wife. Yakov and Raisl Bok, I am sure you will agree, in no way resemble your parents.” Nevertheless, ''The Fixer'' has caused severe confusion concerning Beilis. Some have credited Malamud for inventing aspects of the story that he took from Beilis’ memoir while others have confused Beilis’ character with that of Malamud's character Yakov Bok. As the historian Albert Lindemann lamented: “By the late twentieth century, memory of the Beilis case came to be inextricably fused (and confused) with... ''The Fixer''.”Revival in 2006

In the March 2006 issue (No. 9/160) of the Ukrainian ''Personnel Plus'' magazine by theInterregional Academy of Personnel Management

Interregional Academy of Personnel Management ( uk, Міжрегіональна Академія управління персоналом (МАУП), translit.: ''Mizhrehional'na Akademiya upravlinnya personalom'', English acronym: MAUP) is a pr ...

(commonly abbreviated MAUP), an article titled ''Murder Is Unveiled, the Murderer Is Unknown?'' revived false accusations from the Beilis Trial, stating that the jury had recognized the case as a ritual murder committed by unknown persons, even though it had found Beilis himself not guilty.

In film and literature

* ''The Bloody Hoax'' (originally in Yiddish as ''Der blutike shpas''), 1912–1913, a novel bySholem Aleichem

)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pereiaslav, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = New York City, U.S.

, occupation = Writer

, nationality =

, period =

, genre = Novels, sh ...

whose plot is largely based on details of Beilis Affair.

* ''The Black 107'', 1913 film

* ''The Mystery of the Mendel Beilis Case'', 1914

* ''Delo Beilisa'' (aka ''The Beilis Case''), 1917 film by Joseph Soiffer

* '' The Fixer'', Malamud's 1966 novel, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award

* '' The Fixer'', 1968 film after the novel

* ''Scapegoat on Trial'', 2007, Joshua Waletzky

* "Blood Libel in Late Imperial Russia: The Ritual Murder Trial of Mendel Beilis", 2013, Robert Weinberg

* ''A Child of Christian Blood'', Edmund Levin, 2014

See also

* History of the Jews in Russia and Soviet Union * Antisemitism in Ukraine *Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

* The Fixer (Malamud novel)

* Leo Frank

References

External links

Chabad article on Beilis case

(Beyond the Pale – friends-partners.org) *

*

later issued as a pamphlet *

an

by

Vladimir Korolenko

Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko (russian: Влади́мир Галактио́нович Короле́нко, ua, Володи́мир Галактіо́нович Короле́нко; 27 July 1853 – 25 December 1921) was a Ukrainian-born ...

*Stenographic report from the trial

Volumes 1–3 *

Бейлис, Менахем Мендель

in Shorter Jewish Encyclopedia, Jerusalem. 1976–2005 *

Beilis affair: truth and myth

by Feliks Levitas, Mikhail Frenkel (''Jewish Observer'', Jewish Confederation of Ukraine) April 12, 2006 {{DEFAULTSORT:Beilis, Menahem Mendel 1874 births 1934 deaths People from Kyiv People from Kiev Governorate Ukrainian Jews Antisemitic attacks and incidents in Europe Antisemitism in the Russian Empire Blood libel Jews and Judaism in the Russian Empire Trials in Ukraine 1913 in Judaism Ukrainian emigrants to the United States